“…out of necessity, Bihar State has become the primary testing ground for new therapeutic approaches in visceral leishmaniasis.”

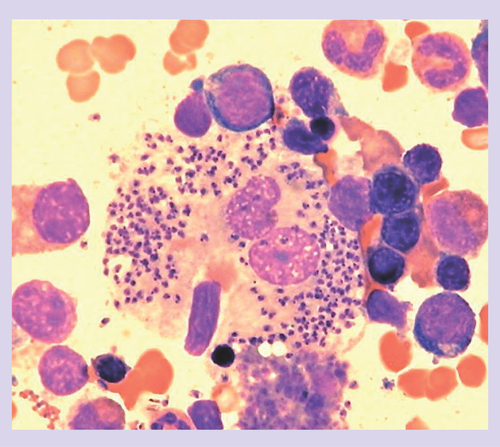

Visceral leishmaniasis (VL), an intracellular protozoal infection that targets tissue macrophages in the liver, spleen and bone marrow, is, seldom encountered in the USA. Nevertheless, my hospital recently cared for an otherwise healthy New York City woman who developed splenomegaly and pancytopenia 4 months after visiting family in her native Greece. Rather than the suspected hematologic malignancy, her bone marrow aspirate showed numerous macrophages parasitized by characteristic Leishmania amastigotes . She was hospitalized, but just for 48 h, to receive two once-daily intravenous infusions of 10 mg/kg liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome®). Treatment was well-tolerated, hematologic recovery was rapid and splenomegaly resolved. She is entirely healthy 6 months after therapy.

Had this same patient been seen in New York City in 2000 rather than in 2010, her clinical outcome would likely have been the same. However, her treatment and experience would have been far different: a more lengthy hospitalization and an arduous 28 days of once-daily intravenous pentavalent antimony (sodium stibogluconate; Pentostam™), accompanied by well-recognized adverse reactions and the requirement for frequent laboratory monitoring Citation[1].

The choice of drug (AmBisome) and regimen (short-course, high-dose) in this patient was based on experience in Mediterranean VL Citation[2], which in turn derived from treatment trials carried out in Bihar State, India, where VL (kala-azar) has been epidemic for decades. This poor, rural region houses approximately 90% of India‘s cases of VL, representing approximately 50% of the world‘s VL burden (estimated at 500,000 new cases per year). More than 10 years ago in Bihar, resistance ended the usefulness of sodium stibogluconate, the traditional treatment worldwide Citation[1]. Thus, during the past decade, out of necessity, Bihar State has become the primary testing ground for new therapeutic approaches in VL. Technically, these new strategies are germane only to anthroponotic Leishmania donovani infection in the Indian subcontinent (India, Bangladesh, Nepal) where VL is generally more treatment-responsive. However, although modifications may be needed depending on the endemic region or complicating factors (e.g., HIV co-infection), approaches developed in Bihar can likely be applied elsewhere as well.

In Bihar, the loss of sodium stibogluconate as the therapeutic cornerstone prompted the rediscovery of amphotericin B deoxycholate, which is effective (>95% cure), but difficult to administer and tolerate. Furthermore, despite the low drug cost, this therapy is expensive (total cost of ∼US$435 per adult treatment course) with prolonged in-hospital treatment (15 alternate-day infusions over 30 days) and laboratory monitoring for toxicity Citation[3]. Against this backdrop, new treatment options were tested in Bihar, yielding, quite rapidly, the following tangible advances, each with cure rates of at least 94–95%:

Short-course (5-day) therapy with lipid formulations of amphotericin B, permitted by the ability of these drugs to directly target tissue macrophages Citation[4,5];

The first and only effective oral therapy with miltefosine (28-day course) Citation[6];

Affordable treatment with the resurrected parenteral agent, paromomycin (21-day course) Citation[7];

Combination short-course (8-day) parenteral–oral therapy using one infusion of AmBisome (5 mg/kg) followed by 1 week of miltefosine Citation[8];

Most recently, the previously tested strategy of single-dose AmBisome alone was also revisited in Bihar; increasing the dose from 5–7.5 to 10 mg/kg proved effective (96% cure) and efficient Citation[9].

“It should come as no surprise that patients may stop self-treatment prematurely as they begin to feel better, and the idea of directly observed therapy has already been suggested.”

In India, and in the continued absence of a vaccine to prevent infection, how to best deploy the preceding treatment advances now lies with the National Kala-Azar Elimination Programme. Established in 2005 by India, Nepal and Bangladesh, this ambitious program seeks to reduce disease prevalence by 20- to 30-fold to less than 1/10,000 population by 2015 Citation[10,11]. In addition to enhanced vector control, rapid noninvasive identification of infected individuals (case finding) and satisfactory detection of initial treatment failures and late relapses, this program‘s success hinges on mass outpatient delivery of optimal therapy. While it is a given that such therapy must be safe, effective (≥95% cure rate) and consistently available, it must also:

Be suitable for administration to tens of thousands of children and adults;

Be efficient (brief);

Require no (or little) laboratory monitoring for toxicity;

Produce near-100% compliance;

Be affordable.

While it is immediately apparent that neither pentavalent antimony and amphotericin B deoxycholate fulfill these criteria, how do the following therapeutic options for the Elimination Programme measure up?

Miltefosine alone

As the only choice for self-administered (oral) and convenient (once- or twice-daily depending on bodyweight) treatment, miltefosine has already been incorporated into the Programme‘s plan. However, concerns include: the long treatment duration (28 days); miltefosine cannot be given to pregnant women; women of childbearing age must use effective contraception during and for at least 3 months after therapy; and self-limited vomiting, diarrhea and raised liver transaminases are not uncommon Citation[6]. In addition, miltefosine is considered expensive at a total cost of approximately $105 per adult course (preferential drug cost ∼$75 plus medical care ∼$30), and concern about compliance with 28 days of therapy has also been raised. Using intention-to-treat analysis, the cure rate in a Phase IV outpatient study in Bihar was only 82% Citation[12]. It should come as no surprise that patients may stop self-treatment prematurely as they begin to feel better, and the idea of directly observed therapy has already been suggested.

Paromomycin alone

Resurrecting this well-tolerated aminoglycoside and making it affordable at a drug cost of $10–15 per adult treatment course (total cost of ∼$40–45) represents real achievements. However, it is difficult to envision the logistics, wide deployment and/or patient acceptability or compliance with once-daily intramuscular injections for 21 consecutive days Citation[7].

Combination therapy

One potential remedy to the problem of duration of miltefosine and paromomycin therapies is using both together or with another drug in a short-course combination regimen. Initial testing of this approach, based on the successful use of one infusion of AmBisome (5 mg/kg) followed by 7 days of miltefosine, has just been completed in Bihar Citation[8]. The regimens of interest in this new study include: the preceding AmBisome–miltefosine 8-day treatment; and full doses of both paromomycin and miltefosine for 10 days. The projected total costs are approximately $110 and $70, respectively.

Single-dose AmBisome®

The 90% reduction in the cost of AmBisome to $20 per 50-mg vial, negotiated in 2007 for use in VL in developing countries (WHO–Gilead Sciences agreement, Gilead AmBisome Access Program Citation[9]), put single-dose AmBisome back on the table of therapeutic options in India. While this approach was initially tested in 2001–2003 using 5 or 7.5 mg/kg Citation[1], the achieved cure rate (90–91%) was below the desired benchmark (≥95%), leading to the recent testing of 10 mg/kg in one infusion. This well-tolerated regimen provided efficacy in children and adults (96% cure), efficiency (patients were safely returned home after an overnight inpatient stay) and, by definition, 100% compliance Citation[9]. At the same time, however, AmBisome requires cold storage and a 1-h intravenous infusion, and even at a further reduced price of $18 per 50 mg, it remains expensive, with a total cost for a 35-kg patient in Bihar of $148 (drug: $126; medical care: $22). If given in an outpatient (daycare) setting, the estimated total cost is still high at $134 per course. While single-dose AmBisome will soon be tested at the district health center and then village levels in Bihar, it remains to be seen exactly how feasible this clinically appealing treatment will be in the much more poorly controlled outpatient setting of rural India.

Conclusion

None of the four preceding approaches fulfills all the criteria for optimal treatment. However, the good news is that the Elimination Programme in the Indian subcontinent does have reasonable options to consider. Perhaps, the program (which will need to move along quite rapidly now to accomplish its goal by 2015) should also incorporate more than one therapeutic approach, so it can provide a more flexible response to the unanticipated issues that are sure to arise during such a large-scale treatment effort.

“One potential remedy to the problem of duration of miltefosine and paromomycin therapies is using both together or with another drug in a short-course combination regimen.”

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The author is supported by NIH grant 1R01AI083219 and received travel funds from Paladin Labs (manufacturer of miltefosine) to attend a scientific meeting in 2009. The author has no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

Bibliography

- Murray HW , BermanJD, DaviesCR, SaraviaNG: Advances in leishmaniasis.Lancet366 , 1561–1577 (2005).

- Syriopoulou V , DaikosGL, TheodoridouMet al. : Two doses of a lipid formulation of amphotericin B for the treatment of Mediterranean visceral leishmaniasis.Clin. Infect. Dis.36 , 560–566 (2003).

- Sundar S , ChakravartyJ, RaiVKet al. : Amphotericin B treatment for Indian visceral leishmaniasis: response to 15 daily versus alternate-day infusions.Clin. Infect. Dis.45 , 556–561 (2007).

- Sundar S , JhaTK, ThakurCP, MishraM, SinghVR, BuffelsR: Low-dose liposomal amphotericin B in refractory Indian visceral leishmaniasis: a multicenter study.Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg.66 , 143–146 (2002).

- Sundar S , MehtaH, SureshAV, SinghSP, RaiM, MurrayHW: Amphotericin B treatment for Indian visceral leishmaniasis: conventional versus lipid formulations.Clin. Infect. Dis.38 , 377–383 (2004).

- Sundar S , JhaTK, ThakurCPet al. : Oral miltefosine for Indian visceral leishmaniasis.N. Engl. J. Med.347 , 1739–1746 (2002).

- Sundar S , JhaTK, ThakurCP, SinhaPK, BhattacharyaSK: Injectable paromomycin for visceral leishmaniasis in India.N. Engl. J. Med.356 , 2571–2581 (2007).

- Sundar S , RaiM, ChakravartyJet al. : New treatment approach in Indian visceral leishmaniasis: single-dose liposomal amphotericin B followed by short-course oral miltefosine.Clin. Infect. Dis.47 , 1000–1006 (2008).

- Sundar SD , ChakravartyJ, AgarwalD, RaiM, MurrayHW: Single-dose liposomal amphotericin B for visceral leishmaniasis in India.N. Engl. J. Med.362 , 504–512 (2010).

- Mondal D , SinghSP, KumarNet al. : Visceral leishmaniasis elimination programme in India, Bangladesh, and Nepal: reshaping the case finding/case management strategy.PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis.3 , e355 (2009).

- den Boer ML , AlvarJ, DavidsonRN, RitmeijerK, BalasegaramM: Developments in the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis.Expert Opin. Emerg. Drugs124 , 395–410 (2009).

- Bhattacharya SK , SinhaPK, SundarSet al. : Phase 4 trial of miltefosine for the treatment of Indian visceral leishmaniasis.J. Infect. Dis.196 , 591–598 (2007).