Abstract

Aim: Four Phase II trials (clinical trials numbers: NCT02345863, NCT02401503, NCT02445131 and NCT02689141) evaluate a different combination of targeted agents in an all-comer population of approximately 60 patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia irrespective of prior treatment, physical fitness and genetic risk factors. Patients with a higher tumor load start with a debulking treatment with bendamustine. The subsequent induction and maintenance treatment with an anti-CD20 antibody (obinutuzumab or ofatumumab) and a targeted oral agent (ibrutinib, idelalisib or venetoclax) are continued until achievement of a complete response and minimal residual disease negativity. Conclusion: This strategy represents a new era of chronic lymphocytic leukemia therapy where chemotherapy is increasingly replaced by targeted agents and treatment duration is tailored to the patient’s individual tumor load and response.

Lay abstract

Four Phase II trials evaluate a different combination of targeted agents in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Only patients with larger lymph nodes or higher lymphocyte counts receive chemotherapy in the beginning. Treatment with the novel agents is continued until no leukemic cells are detected (minimal residual disease negativity). Thus, chemotherapy is increasingly replaced by targeted agents and treatment duration is tailored to the patient’s individual tumor load and the response achieved.

The treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is currently undergoing a profound change; different monoclonal antibodies and targeted agents have become available expanding the therapeutic options. For decades, chlorambucil either alone or with steroids has been the cornerstone in the treatment of CLL, especially for older patients with relevant comorbidities [Citation1–3]. In the 1990s, the combination of different chemotherapeutic agents, for example, fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide led to a significant improvement of response rates and progression-free survival [Citation4–6]. However, the first breakthrough with a prolongation of overall survival came in the following decade with the addition of the monoclonal CD20-antibody rituximab to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide in the first-line treatment of physically fit patients [Citation7,Citation8]. Subsequently two other monoclonal antibodies directed against CD20, ofatumumab and obinutuzumab (formerly GA101), became available and the addition of obinutuzumab to chlorambucil was found to prolong overall survival in elderly comorbid patients [Citation9,Citation10]. Based on these results, chemoimmunotherapy became the standard treatment for both physically fit [Citation7,Citation8,Citation11–14] and unfit patients [Citation9,Citation10]. Our current decade is standing out for the introduction of novel-targeted agents, which were developed based on a growing understanding of the pathogenesis of B-cell lymphomas. Thus far, three novel drugs were approved for CLL: the two kinase inhibitors ibrutinib and idelalisib (formerly CAL-101) both targeting a key enzyme in the B-cell receptor signaling pathway, the BTK and the PI3K, respectively [Citation15–26], as well as the BH3-mimetic venetoclax (ABT-199) inducing programmed cell death of CLL cells through inhibition of the anti-apoptotic BCL-2 protein, which was shown to be upregulated in CLL and linked to chemotherapy resistance [Citation27–33].

Compared with chemotherapy, the anti-CD20 antibodies and the oral-targeted agents are generally well tolerated with a lower risk of severe cytopenias and infections [Citation17–26,Citation31–33]. However, certain typical adverse events (AEs; mostly mild or moderate, i.e., °I–II based on NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events [CTCAE]), such as cutaneous and gastrointestinal reactions (ibrutinib and idelalisib), liver enzyme elevations, colitis and pneumonitis (idelalisib), bleeding events and atrial fibrillation (ibrutinib), tumor lysis syndromes (venetoclax) and infusion-related reactions (anti-CD20 antibodies) need to be considered. In addition, the two B-cell receptor inhibitors cause a lymphocytosis through redistribution of the lymphocytes from the lymph nodes to the peripheral blood, which should not be misinterpreted as a progression of CLL [Citation21,Citation34–36].

The targeted agents ibrutinib, idelalisib and venetoclax are very efficacious [Citation17–26,Citation31–33] and their rapid introduction in the clinical practice has expanded the therapeutic armamentarium and has opened new therapeutic horizons. Previously an allogeneic stem cell transplantation was sought in all physically fit patients with the adverse prognostic markers deletion 17p and/or TP53 mutation despite the considerable morbidity and mortality associated with this procedure. But as the B-cell receptor inhibitors and the BCL-2 antagonist act independently of p53 [Citation37–39], the prognosis of patients with these genetic alterations was considerably improved and the role of allogeneic stem cell transplantation was challenged [Citation40]. Although the outcome of patients with a deletion 17p and/or TP53 mutation is the best ever reported, these genetic alterations appear to retain their adverse prognostic impact as the outcome is still inferior compared with patients without these abnormalities [Citation17,Citation18,Citation26,Citation41]. Thus, the allogeneic stem cell transplantation still plays a role for a highly selected group of patients and offers the possibility of a cure from CLL.

The value of the novel-targeted agents in the treatment of patients with del(17p)/TP53 mutations and in patients with refractory disease is undisputed, but ongoing Phase III trials will have to define their role for other patient groups, for example, in the first-line treatment of patients without high-risk genetic abnormalities. Also, it is uncertain if these drugs should either be used in combination with chemoimmunotherapy in order to further increase the efficacy or if they should rather be used to reduce or even omit the chemotherapeutic agents in order to decrease the risk of toxicities. Another important but so far unanswered question is if these agents should be administered until progression or if treatment can be stopped in case of a deep remission, for example, achievement of minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity. Thus far, it is recommended to continue treatment until progression or unacceptable toxicity, but patient compliance and interactions with other medications will almost certainly become an issue. Furthermore, resistance to ibrutinib seems to arise from a therapeutic pressure leading to a selection of small subclones with resistance mechanisms [Citation42–45]. Possible strategies to avoid this clonal evolution might include a treatment combining agents with different mechanisms of action as well as a discontinuation of treatment in case of a deep remission in order to remove the therapeutic pressure. Lastly, the novel drugs represent a financial burden for our healthcare systems.

‘Sequential triple-T concept’

In order to take advantage of these novel, efficacious and well-tolerated agents and to improve the treatment of CLL, we have proposed a tailored and targeted treatment aiming for a total eradication of MRD [Citation46]. This so called ‘sequential triple-T concept’ consists of the following three treatment phases:

A debulking treatment with up to two cycles of a mild, low-intensity chemotherapy with bendamustine or fludarabine, followed by;

An induction treatment for 6–12 months with an antibody and a kinase inhibitor or BCL-2 antagonist, and;

A MRD-tailored maintenance with the same antibody and kinase inhibitor or BCL-2 antagonist.

BXX trial series

In order to evaluate different combinations of novel antibodies (obinutuzumab or ofatumumab) and novel oral drugs (ibrutinib, idelalisib or venetoclax) and to test if treatment with these agents can be stopped in case of a deep remission, a series of Phase II trials was planned based on the above described ‘triple-T concept’. Due to the promising efficacy and favorable tolerability of these drugs, the feasibility of this concept is evaluated in an all-comer population including first-line, relapsed and refractory CLL patients, regardless of their physical fitness and of adverse prognostic parameters such as del(17p) or TP53 mutations.

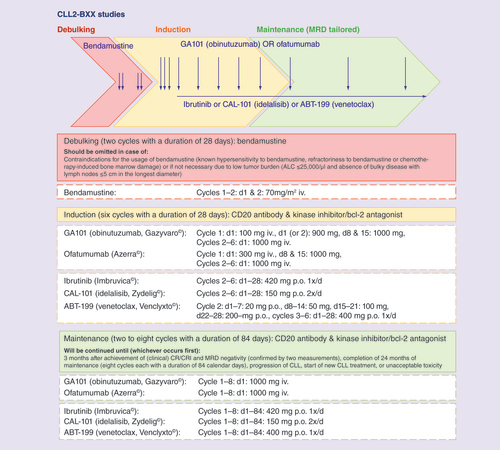

Debulking

For debulking treatment, a mild chemotherapy with two cycles of bendamustine is recommended for all patients unless a contraindication for the use of bendamustine is present or unless it is not clinically indicated based on the following criteria:

Refractoriness to bendamustine (defined as a progression within 6 months after bendamustine-containing therapy);

Myelosuppression caused by previous chemotherapies;

Low tumor burden (e.g., absolute lymphocyte count &25 × 109/l and absence of bulky disease with lymph nodes <5 cm in the longest diameter).

Although the triple-T concept lists both bendamustine and fludarabine as possible chemotherapeutic agents for debulking, the CLL2-BXX trial protocols do not include the option to use another drug in case of contraindications for bendamustine because it would be too unsystematic to allow different types of treatment in one trial.

With the approval of the patient for trial enrollment, a recommendation regarding the administration of a debulking is given by the GCLLSG study office after a medical review of the results of the central diagnostics, as well as the information about the patient’s pretherapeutic staging and his/her previous treatments.

The debulking consists of two cycles with a dosage of 70 mg/m2 bendamustine on days 1 and 2. Bendamustine was selected as it combines the chemical properties of an alkylator and a purine analog and because it is generally well tolerated and efficacious as a single agent as well as in combination with rituximab [Citation12,Citation47–49]. The dosage of 70 mg/m2, which is usually administered in relapsed patients, was determined because the debulking treatment is only used to reduce the tumor load prior to treatment with antibody and inhibitors in order to decrease the risk of infusion-related reactions and tumor lysis syndromes. In addition, the debulking step is designed to achieve faster remissions than with targeted agents alone. In general, patients undergoing a debulking step should receive two cycles of bendamustine, unless relevant toxicities occur during the first cycle.

Induction

Whereas the criteria for debulking, the dosage and schedule of bendamustine are similar in all trials from the BXX series, each of the trials evaluates a different combination of antibody and kinase inhibitor/BCL-2 antagonist in the induction and maintenance phase. The acronym of each trial represents the first letters of the current or previous names of the drugs used in the treatment combination:

CLL2-BIG: bendamustine, followed by ibrutinib and GA101 (obinutuzumab);

CLL2-BAG: bendamustine, followed by ABT-199 (venetoclax) and GA101 (obinutuzumab);

CLL2-BCG: bendamustine, followed by CAL-101 (idelalisib) and GA101 (obinutuzumab);

CLL2-BIO: bendamustine, followed by ibrutinib and ofatumumab.

In order to reduce the risk of tumor lysis syndromes and of infusion-related reactions (especially in patients without a prior debulking with bendamustine or in case the tumor load is still high despite the debulking), the induction treatment starts with the antibody as a single agent. The kinase inhibitor/BCL-2 antagonist is added subsequently in the second cycle. In the CLL2-BIG, -BCG and -BIO trials with the kinase inhibitors ibrutinib or CAL-101 (idelalisib), this was planned because of concerns that the frequently observed lymphocytosis under ibrutinib and idelalisib therapy might increase the risk of infusion-related reactions. In the CLL2-BAG trial, the subsequent start of GA101 (obinutuzumab) and ABT-199 (venetoclax) was implemented to reduce the tumor load before starting with ABT-199 (especially in patients without a debulking treatment) and also to avoid overlapping toxicities, in other words, a potentiating effect with both agents putting the patient at risk of a tumor lysis syndrome. Although data have become available suggesting that a simultaneous start of kinase inhibitor and rituximab might reduce the risk of infusion-related reactions [Citation50], the situation remains less clear with obinutuzumab, the more potent antibody. Therefore, we chose to maintain the sequence to minimize the acute infusion-related toxicity of the therapy.

As a consequence, the antibody (obinutuzumab or ofatumumab) is administered as a single agent in the first induction cycle in all four trials, and the kinase inhibitor or BCL-2 antagonist (ibrutinib, idelalisib or venetoclax) is added in the second induction cycle. The treatment schedule of the drugs in the BXX trials is consistent with the dosing and administration schedule established in previous trials (). As all combinations include two agents with different mechanisms of action, no overlapping or cumulative toxicities were expected. According to the usual treatment schedule of both antibodies, these are administered with a lower ‘test-dose’ on the first day, which is followed by two additional dosages on days 8 and 15 in the first induction cycle in order to achieve sufficient plasma levels. Starting on the first day of the second cycle, the two kinase inhibitors ibrutinib and idelalisib are administered continuously with a fixed dosage of 420 mg once daily or 150 mg twice daily, respectively. The BCL-2 antagonist ABT-199 is started with a low initial dosage of 20 mg, which is increased on a weekly basis over 5 weeks to the target dosage of 400 mg daily. Also, several safety measures for prevention and early detection of tumor lysis syndromes are necessary, including hydration, administration of uric acid reducers, laboratory monitoring and hospitalization (depending on the patient’s individual tumor lysis risk).

ALC: Absolute lymphocyte count; CLL: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CR: Complete remission; CRi: Complete remission with incomplete recovery of the bone marrow; d: Day; iv.: Intravenous; MRD: Minimal residual disease; p.o.: Per orem.

Aside from the premedication for the antibody infusions and the safety precautions for venetoclax, all other prophylactic medications, for example, antiemetic drugs during debulking, as well as anti-infective prophylaxis and growth factors were recommended to be used at the investigator’s discretion and according to institutional practice.

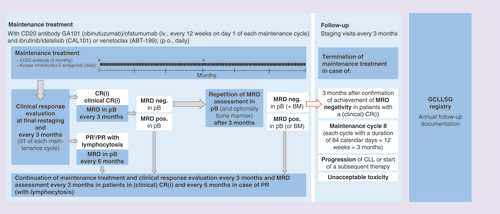

Maintenance

After completion of six induction cycles and two staging examinations (including the final restaging 2 months after the last induction cycle, representing the primary end point of the trial), all patients benefitting from continuous study treatment enter a maintenance phase. While the oral drugs (kinase inhibitors or BCL-2 antagonist) is continued daily during staging phase and maintenance treatment, the antibody is administered every 12 weeks in the maintenance phase (4 weekly in the induction phase). Although 2 monthly antibody administrations are established in the maintenance treatment of CLL and other types of lymphoma [Citation51–55], in the BXX trials, the intervals are expanded to 3 monthly in order to avoid a long lasting B-cell depletion and allow a transient recovery. Furthermore, the antibody is used in combination with another targeted agent in these trials.

This maintenance treatment will be continued either for up to 2 years (i.e., eight cycles each with a duration of 12 weeks) or until disease progression/start of a novel CLL treatment, until intolerable toxicity or until withdrawal of consent. Furthermore, the maintenance treatment will be stopped in case of a complete remission (CR) and MRD negativity, which is an innovative approach in the treatment of CLL since the kinase inhibitors are usually administered as long as tolerated or until progression.

MRD-triggered end of maintenance

As repeated bone marrow biopsies for assessment of MRD would not be tolerated by the patients and should not become routine practice, MRD will be measured in the peripheral blood. However, additional bone marrow samples may be taken in patients voluntarily agreeing to this procedure. All MRD analyses are performed by four-color flow cytometry in the central laboratory in Kiel using a method that has been extensively validated against allele-specific oligonucleotide real-time quantitative PCR [Citation56]. Results are categorized into three different MRD levels: low (<10-4, i.e., <1 CLL cells per 10,000 leukocytes), intermediate (≥10-4 and <10-2) and high (≥10-2) [Citation57]. MRD negativity is arbitrarily defined as <10-4 and patients are defined as MRD negative if their disease burden is below this threshold.

MRD is assessed in all patients at the final restaging 2 months after the last induction cycle and will be reported together with the overall response rate (ORR), which is the primary end point of the trials. Afterwards, the frequency of MRD assessments during the maintenance phase depends on the patient’s type of response; MRD will be assessed at every staging (i.e., 3 monthly) in patients with a complete remission (CR), including CRs with incomplete recovery of the bone marrow (CRi) as well as CRs without confirmatory bone marrow biopsy and/or CT/MRI scan (unconfirmed ‘clinical CR’). Patients with a partial response (PR) with or without treatment-associated lymphocytosis [Citation21,Citation35] will undergo MRD assessments at every other staging (i.e., 6 monthly) until improvement to a CR/CRi. While the 3 monthly MRD assessments for patients with a CR are used to guide the duration of maintenance treatment, the 6 monthly assessments for patients with a PR are performed primarily for scientific reasons. Patients with an excellent PR, who only fail to meet the criteria for a CR because of a persisting splenomegaly or lymph nodes, which are considered an inactive remainder of previous massive enlargement by the treating physician [Citation58], may also undergo 3 monthly MRD assessments and terminate maintenance therapy in case of MRD negativity at the treating physician’s discretion. This exception was included into the trial protocols because in some cases a massive splenomegaly or huge lymph node bulk improves over a certain time period and then remains stable with a slightly increased size, which is often rather a remainder of the previous massive enlargement of the tissue and not residual infiltration by CLL. Patients with these residual lymph nodes or splenomegaly do not meet the iwCLL criteria for a complete remission; however, an analysis of patients treated with chemo(immuno)therapy in the CLL8 and CLL10 trials demonstrated that the outcome of patients with a partial response who become minimal residual disease negative is equal to the outcome of patients with a complete response and minimal residual disease negativity [Citation58].

The maintenance treatment is stopped in patients with a CR/CRi (and similarly also patients with a ‘clinical CR/CRi’ or a PR due to residual, presumably inactive lymphadenopathy/splenomegaly) if two MRD assessments within an interval of 3 months show a negative result. The maintenance treatment is continued between the two assessments and one additional maintenance cycle (3 months) is administered after the second, confirmatory MRD assessment (). This continuation of maintenance treatment aims to increase the depth of response, as it is known that MRD negativity in the peripheral blood is less sensitive than MRD negativity in the bone marrow (at least in case of treatment with chemo[immuno]therapy) [Citation57,Citation59,Citation60]. In addition to the purpose of consolidation, this procedure offers a practical advantage; as the MRD analyses take a few days, patients would have to see their physician twice, one appointment for the staging with the MRD sampling and a second appointment with the MRD result available for deciding if maintenance treatment will be continued. With the additional 3 months of maintenance treatment, it is feasible that patients tolerating the treatment will require only one appointment at the beginning of each cycle, during which all staging procedures, including MRD sampling, the administration of the antibody and the dispensing of the oral study drug for the next 3 months is performed.

†Some patients may be in a PR according to International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia criteria, but clinically have a CR, e.g., due to a persisting enlargement of the spleen or lymph nodes, that seems to be a residuum of previous CLL involvement and does not improve over time during maintenance treatment. These patients may be treated as patients in (clinical) CR after discussion with the GCLLSG study physician, i.e., receive 3 monthly MRD assessments and terminate maintenance in case of achievement of MRD negativity (confirmed with two consecutive measurements).

CR: Complete remission; CRi: Complete remission with incomplete recovery of the bone marrow; iv.: Intravenous; MRD: Minimal residual disease; neg.: Negative; p.o.: per orem; pos.: Positive; PR: Partial response.

After termination of maintenance, all patients will be followed in 3-monthly intervals for 6–24 months (depending on the duration of maintenance treatment) for assessment of response duration and survival analyses as well as toxicity. In addition, patients will be included in the registry of the German CLL Study Group in order to collect data on longer follow-up and long-term toxicities.

Key eligibility criteria

As mentioned above, the trials were designed for an all-comer population of physically fit and unfit, previously treated and treatment-naive CLL patients with and without adverse prognostic parameters, such as del(17p) and TP53 mutations. Even if the target population of these trials is very heterogeneous, certain inclusion and exclusion criteria had to be defined in order to select the right patients for trial participation and prevent excess of certain toxicities.

Eligible patients are required to have a centrally confirmed diagnosis of CLL according to International Workshop for CLL (iwCLL) criteria (lymphocytosis with ≥5x 109/l clonal B-lymphocytes in the peripheral blood, a peripheral blood smear with small, morphologically mature lymphocytes and an immunophenotype with a coexpression of the T-cell antigen CD5 with B-cell surface antigens CD19, CD20 and CD23 and an expression of either K or Λ immunoglobulin light chains) [Citation34]. Inclusion of patients with small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) was not permitted because of differences in patient management, for example, use of the Ann-Arbor staging system instead of the Binet or Rai classification. The CLL had to require treatment according to iwCLL criteria [Citation34], for example due to advanced Binet stage C disease (defined by an anemia <10 g/dl and/or thrombocytopenia <100,000/μl), or Binet stage A or Binet stage B with a massive or symptomatic lymphadenopathy or splenomegaly, a rapid lymphocyte doubling time or constitutional symptoms, such as night sweats, weight loss (≥10% within 6 months) or fever without evidence of infection. With the exception of the CLL2-BCG study which had to be amended (see the third paragraph of the ‘Current status of the BXX trials’ section), the trials were designed for both treatment naive and previously treated patients. Relapsed/refractory patients must have recovered from all acute toxicities and previous treatment regimen must be stopped within certain time periods before the initiation of the study treatment: chemotherapy must be discontinued within ≥28 days, antibody treatment within ≥14 days and kinase inhibitors, BCL-2 antagonists or immunomodulatory agents within ≥3 days; corticosteroids may be applied until the start of study treatment but have to be reduced to an equivalent of ≤20 mg prednisolone during treatment. Although the wash-out periods, especially of the antibodies, are certainly longer, these time periods were chosen as short as possible to allow the inclusion of patients progressing during the previous therapy, but to assure a recovery of the patients from the acute AEs and to avoid cumulative toxicities. In case of a progression during treatment with a kinase inhibitor, the treatment is usually continued until the start of the next treatment line in order to avoid an accelerated progression with rapid swelling of lymph nodes.

Patients must have an adequate renal and liver function (defined as a creatinine clearance ≥30 ml/min and a total bilirubin ≤2× [≤1.5× in CLL2-BCG] and AST/ALT ≤2.5× the institutional upper limit of normal [ULN] value, unless directly attributable to the patient’s CLL or to Gilbert’s Syndrome), as well as an adequate hematologic function (platelet count ≥25 × 109/l, a neutrophil count ≥1 × 109/l and a hemoglobin value ≥8.0 g/dl, unless directly attributable to the patient’s CLL [e.g., bone marrow infiltration]). In addition, serological testing for hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus as well as HIV infections must be negative; however, patients positive for anti-HBc may be included if PCR for HBV-DNA is negative and HBV-DNA PCR is performed regularly during and after antibody treatment.

Even if the trials were designed for an all-comer population and include also physically unfit patients, inclusion of patients with certain comorbidities is not permitted because of safety concerns. All four BXX trials exclude patients with a single comorbidity or organ system impairment rated with a cumulative illness rating scale score of four (excluding the eyes/ears/nose/throat/larynx organ system). Also excluded are patients with any other life-threatening illness, medical condition or organ system dysfunction that – in the investigator’s opinion – could compromise the patient’s safety or interfere with the absorption or metabolism of the study drugs (e.g., inability to swallow tablets or impaired resorption in the GI tract). In addition, certain exclusion criteria were deemed necessary due to the specific toxicity profile of the oral drugs. Concomitant use of strong CYP3A4/5 inhibitors/inducers as well as vitamin-K antagonists, for example, warfarin and phenprocoumon is prohibited in the CLL2-BIG, -BAG and -BIO trials due to the metabolism and risk of interactions with ibrutinib and ABT-199 (venetoclax). Patients with a history of stroke or intracranial hemorrhage within 6 months prior to registration are excluded from the CLL2-BIG and -BIO trials due to an increased risk of bleeding events with ibrutinib. Patients with drug-induced pneumonitis or inflammatory bowel disease are excluded from the CLL2-BCG trial due to the specific autoimmune risks with idelalisib.

All four BXX trials exclude patients with a transformation or CNS involvement of CLL as well as patients with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, an uncontrolled infection requiring treatment or a malignancy other than CLL requiring systemic treatment. Furthermore, patients are required to have a life expectancy ≥6 months and an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0–2 (ECOG 3 is permitted if related to CLL, for example, due to anemia or severe constitutional symptoms).

Objective

These four Phase II trials aim to evaluate the feasibility of a sequential treatment regimen consisting of a debulking treatment with bendamustine followed by an induction and maintenance treatment with the combination of an antibody (obinutuzumab [GA101] or ofatumumab) and an oral-targeted drug (ibrutinib, idelalisib [CAL-101] or venetoclax [ABT-199]). The primary end point of all four trials is the overall response rate (ORR) at the final restaging, performed 2 months after the last induction cycle before the start of maintenance treatment. Secondary end points include ORR at the end of maintenance, CR and MRD-negativity rate, progression-free and overall survival as well as safety analyses.

Assessment

Before inclusion into the trial, the diagnosis of CLL is confirmed centrally by immunophenotyping. Also, the most relevant risk factors (including cytogenetics, molecular genetics [especially IGHV and TP53] and the serum parameters beta-2-microglobulin and thymidine kinase) are assessed in the central laboratories of the GCLLSG. In addition, samples for accompanying scientific research projects including genome and exome sequencing are drawn and leftovers of the central diagnostics are stored in a biobank for subsequent analyses if patients agree.

At the time point of progression of the patients, the genetic analyses and also genome/exome sequencing will be repeated in order to study the reasons for failure of treatment with these novel drugs.

All patients receiving at least one dose of study treatment belong to the safety population and will be evaluated for toxicity during and after treatment. In addition to serious AEs (SAEs), AEs of particular interest, which are related to the CLL, for example, infections and autoimmune diseases, and AEs of special interest, which are related to the study drug, for example, infusion-related reactions during antibody treatment, bleeding events with ibrutinib, pneumonitis with idelalisib and tumor lysis syndromes with venetoclax will be reported irrespective of severity and seriousness as SAEs until the end of the trial.

During and after end of treatment, staging procedures will be performed every 3 months in all patients including a complete blood count, a clinical examination with focus on lymph nodes, liver and spleen, as well as atypical CLL manifestations and history of the patient’s wellbeing, especially constitutional symptoms. A radiological assessment using CT or MRI scan or ultrasound is requested for the initial staging at screening and for the final restaging after induction treatment (primary end point); in the CLL2-BAG trial, a CT/MRI scan is mandatory before the administration of venetoclax for a reliable determination of the risk group for tumor lysis syndrome. The response to treatment will be assessed according to the iwCLL guidelines with the modification regarding the treatment-related lymphocytosis, which should not be considered as a sign of progression [Citation34,Citation35].

As described above, MRD will be measured in the peripheral blood in all patients at the final restaging and every 3 months in all patients with a complete remission (CR, including also patients with a CRi and an unconfirmed ‘clinical CR or CRi’) and every 6 months in patients with a PR (including patients with a PR with lymphocytosis). An examination of bone marrow, including assessment of MRD, should be performed whenever clinically indicated and in patients with a CR who voluntarily agree to this procedure.

Patient population & statistical analyses

The primary end point of ORR at final restaging 2 months after end of induction treatment will be analyzed for the full analysis set, which comprises all enrolled patients who received at least two complete induction cycles (according to an intention-to-treat principle for nonrandomized trials). The ORR is defined as the proportion of patients having achieved a CR/CRi, ‘clinical CR/CRi’, PR or PR with lymphocytosis. However, patients without any documented response assessment will be kept and labeled as ‘nonresponder’ in the analysis. Additionally, the best response rate until 6 months after final restaging, the response to debulking and maintenance treatment, as well as responses in previously untreated and relapsed/refractory patients and responses in biologically defined risk groups will be assessed as secondary end points. Also, CR and PR rates, MRD-negative responses and progression-free, event-free and overall survivals are additional efficacy end points. Regarding safety, type, frequency and severity of AEs and AEs of special interest (see the definition of AEs of special interest in the ’Assessments’ section) and their relationship to study treatment will be evaluated based on all patients who received at least one dosage of study treatment (including debulking).

As for the study assumptions, efficacy of each of the four BXX regimens is confirmed if the ORR at the final restaging after induction treatment is at least 90% (response rate of an active regimen) and is assessed to be not effective if the ORR is less than 75% (ORR of an uninteresting regimen). This lower boundary of efficacy of 75% ORR corresponds to an expected ORR of a mixed CLL population and is composed of the expected ORR of relapsed/refractory as well as previously untreated first-line patients. For relapsed/refractory patients, an ORR of 64% is expected and for first-line patients it is expected to achieve an ORR of approximately 90%. Concerning different allocations of relapsed/refractory and first-line patients, a fixed lower limit of a third and an upper limit of two-thirds will be considered resulting in a flexible recruitment of a third to two-thirds per stratum.

Sample size

The primary end point ORR after induction treatment was used to determine the sample size of the study and the following study assumptions are considered. As stated previously, the ORR rate for an uninteresting regimen is assumed to be 75% with corresponding null hypothesis (H0): ORR ≤0.75. It is aimed to improve this rate to at least 90% (H1: ORR ≥0.9) with the BXX regimen. The type I error of 5% defines the chance that the BXX regimen will be investigated further although the true ORR is lower or equal to 75%. The type II error is the chance that an effective treatment will not be studied further. This should not exceed β = 20%, so that it is aimed to achieve a power of at least (1 - β) = 80%.

According to the above determined study parameters, a two-sided, one-sample binomial test with an overall significance level of 5% will have at least 80% power to detect the stated improvement in ORR from 75 to 90% when the total number of patients is 54. To account for a mixed CLL population consisting of relapsed/refractory and first-line patients and to ensure the 80% power, it was considered necessary to enroll eight additional patients (including a 10% drop-out rate approximately). Thus, 62 patients have to be recruited in total to each of the four BXX trials, among them at least 21 each had to be treatment naive and relapsed/refractory (with a flexible recruitment of the remaining 20 patients).

Time point of analyses

Each of the four BXX trials will be analyzed individually; the first analysis of the primary end point ORR at the final restaging after induction treatment may be performed at the earliest opportunity once all patients from the full analysis set have reached the final restaging, which is approximately 10 months after the last patient entered the trial. Further analyses of the secondary end points will be performed as soon as possible.

It needs to be stressed that these trials are not designed and powered for comparing the different combinations of drugs tested in the four BXX trials. Furthermore, the comparisons of the different combinations would be hampered by the heterogeneity of the patient populations, as the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the four trials allow the recruitment of an all-comer population and the proportion of treatment-naive and relapsed/refractory patients, physically fit and unfit patients, as well as patients with and without adverse prognostic parameters will differ considerably across the trials.

Current status of the BXX trials

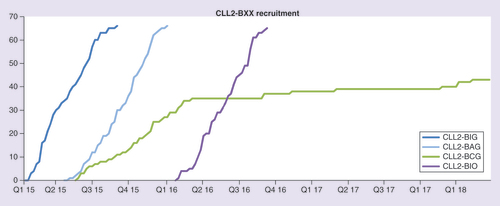

Each of the four multicenter, open-label Phase II trials is conducted separately at 20 sites in Germany, only the four key sites of the GCLLSG participate in all trials. The trials were activated sequentially with overlapping recruitment periods ().

CLL2-BIG, -BAG and -BIO have completed recruitment faster than expected and the primary end point analysis for CLL2-BIG, -BAG and -BIO is under way. Regular evaluations of the SAEs of all trials showed no unexpected or cumulative toxicities; in particular, no clinical and only few laboratory tumor lysis syndromes occurred with the CLL2-BAG regimen. Also, the bendamustine debulking appeared to reduce the risk of infusion-related reactions in the first induction cycle with obinutuzumab, as intended by the trial concept [Citation61–63].

However, the CLL2-BCG trial had to be withheld due to novel safety data regarding idelalisib, which revealed an increased risk of infections (including opportunistic infections with cytomegalovirus or Pneumocystis jirovecii) and a higher treatment-related mortality with idelalisib as first-line treatment. Since these problems were not seen in trials evaluating idelalisib in patients with relapsed CLL, for example, combined with rituximab or bendamustine/rituximab, it was decided to continue the CLL2-BCG trial with changed inclusion/exclusion criteria in order to stop recruitment of treatment-naive patients and to limit the relapsed/refractory stratum to patients with the high-risk features del(17p)/TP53 mutation and/or patients who are ineligible to receive ibrutinib. Furthermore, the amendment included additional safety precautions (e.g., more frequent laboratory monitoring, including for cytomegalovirus) and an extensive accompanying scientific program aiming at elucidating the changes in the immune system modulation during treatment and gain an insight into the pathogenesis of autoimmune phenomena and infectious complications with idelalisib.

Conclusion & future perspective

This series of four Phase II trials is based on the theoretical ‘triple-T concept’ of tailored and targeted regimens aiming at a total eradication of CLL as proposed by the German CLL Study Group at the Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology 2013. Each trial consists of a debulking treatment with bendamustine, followed by an induction and a maintenance treatment with the combination of an anti-CD20 antibody and a kinase inhibitor or BCL-2 antagonist: ibrutinib and GA101 (obinutuzumab) in the CLL2-BIG trial, ABT-199 (venetoclax) and GA101 in CLL2-BAG, CAL-101 (idelalisib) and GA101 in CLL2-BCG and ibrutinib and ofatumumab in the CLL2-BIO trial. The administration of the debulking with bendamustine is dependent on the patient’s individual tumor load, and the duration of the maintenance treatment is tailored to the time point of achievement of a response, as the maintenance treatment will be terminated once a complete response and total eradication of the disease (MRD negativity) is achieved. All four trials are run separately and include an all-comer population of first-line and relapsed/refractory, physically fit and comorbid patients, as well as patients with and without adverse prognostic parameters. Due to the limited patient number and imbalances in the patients’ characteristics across the four trials, cross-trial comparisons of the different regimens cannot identify which therapeutic combination is the best. However, the trials might demonstrate that these regimens are highly effective and well tolerated, and thus serve as a proof of principle for this sequential, targeted and tailored, in other words, more personalized therapeutic approach. The experience gained in the patients included into these trials at our sites is very promising as patients seem to tolerate the regimens very well and seem to achieve very fast and deep remissions. Furthermore, no unexpected toxicities were reported as SAEs. In addition, the consultations with our patients as well as the very fast recruitment of these trials reflect the desires of the patients to avoid chemotherapy and terminate treatment in case of a deep remission, instead of being continuously treated beyond response.

Should the trials meet the expectations, achieve an ORR of ≥90% and demonstrate that a termination of treatment is feasible in patients with a complete, MRD-negative response, the current practice of administering the novel-targeted agents as a monotherapy until progression would be challenged. Consequently, this would stir up the debate of the fundamental question, whether treatment of CLL should rather be less toxic but continuous or more intense but with a limited duration. Presumably, the answer will differ for distinct patient groups, for example, depending on their age, comorbidities, CLL-related risk factors as well as patient’s wishes and expectations. However, since these BXX regimens aim at an eradication of MRD to allow a treatment discontinuation, the next step would be to identify patients who will not respond sufficiently at an early time point in order to change or intensify the treatment before the disease becomes refractory. It would be desirable to guide the choice of the targeted agents and treatment intensity with a biological parameter, however, the identification of a predictive biomarker will require large cohorts and therefore will take time. An alternative approach could be to define a time point at which a certain depth of response needs to be achieved or to assess the kinetics of response of the individual patients and to change/intensify the treatment in case of a worse or slower response.

These four Phase II trials will help to find answers to some of the current clinical problems in the treatment of CLL but they will certainly also raise additional questions and necessitate further trials to increase the knowledge about the mechanism of action of the novel drugs and how to best combine them in the management of CLL. Several Phase III trials evaluating different combinations of novel-targeted agents are already under way, for example, the CLL13 trial (NCT02950051) in treatment-naive, physically fit CLL patients. A four-arm design compares standard chemoimmunotherapy (rituximab combined with either fludarabine and cyclophosphamide or bendamustine) versus venetoclax plus either rituximab or obinutuzumab versus venetoclax, obinutuzumab and ibrutinib. This trial, especially its arm with the triple combination, aims at very deep responses to ultimately cure this disease.

‘Sequential triple-T concept’

The therapeutic landscape for lymphomas, including chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), is currently undergoing dramatic changes with several very efficacious and well-tolerated novel agents becoming available.

In order to take advantage of the opportunities of these novel agents, the GCLLSG proposed the theoretical ‘sequential triple-T concept’ with a targeted, tailored treatment aiming for a total eradication of CLL. This treatment concept comprises a debulking treatment with a mild chemotherapy, followed by an induction and a maintenance treatment with a combination of targeted agents, which will be terminated in case of a complete response and minimal residual disease negativity, in other words, an eradication of disease below the detection limit.

BXX trial series

The idea of the ‘sequential triple-T concept’ was realized in four Phase II trials for an all-comer CLL population. Each trial evaluates a debulking with two cycles of bendamustine, followed by an induction and a maintenance treatment with a different combination of CD20-antibody and kinase inhibitor or BCL-2 antagonist.

The CLL2-BIG trial with ibrutinib and GA101 (obinutuzumab), the CLL2-BAG trial with ABT-199 (venetoclax) and GA101 and the CLL2-BIO trial with ibrutinib and ofatumumab have completed recruitment, the primary end point analyses are under way.

The CLL2-BCG trial with CAL-101 (idelalisib) and GA101 (obinutuzumab) had to be amended due to novel safety data from other trials; recruitment is now limited to relapsed/refractory patients with the high-risk features del(17p)/TP53 mutation and/or patients who are ineligible to receive ibrutinib. Furthermore, additional safety precautions and an extensive accompanying scientific program were included.

Preliminary clinical experience from the patients included at our own sites up to date is very promising for all four trials and serious adverse events are consistent with those previously reported for the novel drugs.

Objective

The primary end point of all four trials is the overall response rate at the final restaging 2 months after end of induction treatment, which should be ≥90% to confirm the efficacy of the regimen.

Furthermore, these trials will help to answer the question if treatment with the kinase inhibitors can be terminated in case of a deep remission (minimal residual disease negative complete remission) and thus might lead to an individualization of treatment duration.

Acknowledgements

These four trials are investigator-initiated trials with the University of Cologne being the legal sponsor. The following pharmaceutical companies provided financial support and the study drugs: F Hoffmann-LaRoche (CLL2-BIG, -BAG and -BCG), Janssen–Cilag (CLL2-BIG and -BIO), Gilead (CLL2-BCG) and GlaxoSmithKline/Novartis (CLL2-BIO); whereas AbbVie provided study drug (CLL2-BAG). The authors wish to express their gratitude towards all patients participating in the trials and their families, as well as the physicians and trial staff at the sites. Also, we thank the study management team with the project managers Johanna Wesselmann and Tanja Annolleck, as well as Jana Kalz and Marina Stockem, the safety managers Sabine Frohs and Tanja Annolleck, as well as Miriam Thiel and Kerstin Loeschke, the data managers Irene Stodden, Viktoria Monar, Olga Korf, Florian Drey, as well as Annette Beer, Carlo Eichendorf, Ute Elberskirch and Swetlana Dubnov and last but not least Dr Birgit Fath and the monitors from the competence network malignant lymphoma (“Kompetenznetz Maligne Lymphome”).

Financial & competing interests disclosure

P Cramer: research funding by F Hoffmann-LaRoche, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen–Cilag and Novartis, honoraria for scientific talks by F Hoffmann-LaRoche and Janssen–Cilag, advisory boards by AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Janssen–Cilag and Novartis, travel grants by Astellas, F Hoffmann LaRoche, Gilead, Janssen–Cilag and Mundipharma. J von Tresckow: research funding by F Hoffmann-LaRoche and Janssen–Cilag, honoraria by AbbVie, F Hoffmann-LaRoche and Janssen–Cilag, travel grants by Celgene, F Hoffmann-LaRoche and Janssen–Cilag. J Bahlo: honoraria by F Hoffmann-LaRoche, travel grants by F Hoffmann-LaRoche. A Engelke: travel grants by F Hoffmann-LaRoche. P Langerbeins: research funding, travel grants and honoraria by F Hoffmann-LaRoche, Janssen–Cilag and Mundipharma. AM Fink: research funding by Celgene, travel grants by F Hoffmann-LaRoche, Mundipharma, Abbvie and Celgene, and honoraria by F Hoffman-LaRoche. K Fischer: travel grants from Roche. CM Wendtner: consultant or advisory board member, research support and travel support by AbbVie, F Hoffmann-LaRoche, Genentech, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen–Cilag, Mundipharma and Pharmacyclics. KA Kreuzer: consultant or advisory board member, honoraria and research support by AbbVie, Amgen, F Hoffmann-LaRoche, Gilead, Janssen–Cilag and Mundipharma. S Stilgenbauer: consultant or advisory board member, research support and travel support by AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Celgene, F Hoffmann-LaRoche, Genentech, Genzyme, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen–Cilag, Mundipharma, Novartis and Pharmacyclics. S Böttcher: research funding by AbbVie, Celgene and F Hoffmann-LaRoche, honoraria for consultancy or advisory boards by AbbVie and F Hoffmann-LaRoche. B Eichhorst: consultant or advisory board member, research support or travel support by AbbVie, Celgene, F Hoffmann-LaRoche, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen–Cilag, and Mundipharma. M Hallek: consultant or advisory board member, honoraria andresearch support by AbbVie, Amgen, Celgene, F Hoffmann-LaRoche, Gilead, Janssen–Cilag and Mundipharma. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Eichhorst BF , BuschR, StilgenbauerSet al. First-line therapy with fludarabine compared with chlorambucil does not result in a major benefit for elderly patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood114(16), 3382–3391 (2009).

- Han T , EzdinliEZ, ShimaokaK, DesaiDV. Chlorambucil vs. combined chlorambucil–corticosteroid therapy in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer31(3), 502–508 (1973).

- Knospe WH , LoebVJr. Biweekly chlorambucil treatment of lymphocytic lymphoma. Clin. Trials3(4), 329–336 (1980).

- Eichhorst BF , BuschR, HopfingerGet al. Fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide versus fludarabine alone in first-line therapy of younger patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood107(3), 885–891 (2006).

- Flinn IW , NeubergDS, GreverMRet al. Phase III trial of fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide compared with fludarabine for patients with previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia: US Intergroup Trial E2997. J. Clin. Oncol.25(7), 793–798 (2007).

- Catovsky D , RichardsS, MatutesEet al. Assessment of fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (the LRF CLL4 trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet370(9583), 230–239 (2007).

- Hallek M , FischerK, Fingerle-RowsonGet al. Addition of rituximab to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a randomised, open-label, Phase III trial. Lancet376(9747), 1164–1174 (2010).

- Fischer K , BahloJ, FinkAMet al. Long-term remissions after FCR chemoimmunotherapy in previously untreated patients with CLL: updated results of the CLL8 trial. Blood127(2), 208–215 (2016).

- Goede V , FischerK, BuschRet al. Obinutuzumab plus chlorambucil in patients with CLL and coexisting conditions. N. Engl. J. Med.370(12), 1101–1110 (2014).

- Goede V , FischerK, EngelkeAet al. Obinutuzumab as frontline treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: updated results of the CLL11 study. Leukemia29(7), 1602–1604 (2015).

- Byrd JC , RaiK, PetersonBLet al. Addition of rituximab to fludarabine may prolong progression-free survival and overall survival in patients with previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia: an updated retrospective comparative analysis of CALGB 9712 and CALGB 9011. Blood105(1), 49–53 (2005).

- Eichhorst B , FinkAM, BahloJet al. First-line chemoimmunotherapy with bendamustine and rituximab versus fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab in patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL10): an international, open-label, randomised, Phase III, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol.17(7), 928–942 (2016).

- Robak T , DmoszynskaA, Solal-CelignyPet al. Rituximab plus fludarabine and cyclophosphamide prolongs progression-free survival compared with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide alone in previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol.28(10), 1756–1765 (2010).

- Tam CS , O’BrienS, WierdaWet al. Long-term results of the fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab regimen as initial therapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood112(4), 975–980 (2008).

- Herman SE , GordonAL, WagnerAJet al. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-delta inhibitor CAL-101 shows promising preclinical activity in chronic lymphocytic leukemia by antagonizing intrinsic and extrinsic cellular survival signals. Blood116(12), 2078–2088 (2010).

- Maddocks K , JonesJA. Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibition in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Semin. Oncol.43(2), 251–259 (2016).

- Byrd JC , BrownJR, O’BrienSet al. Ibrutinib versus ofatumumab in previously treated chronic lymphoid leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med.371(3), 213–223 (2014).

- Furman RR , SharmanJP, CoutreSEet al. Idelalisib and rituximab in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med.370(11), 997–1007 (2014).

- Byrd JC , FurmanRR, CoutreSEet al. Targeting BTK with ibrutinib in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med.369(1), 32–42 (2013).

- O’Brien S , JonesJA, CoutreSEet al. Ibrutinib for patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia with 17p deletion (RESONATE-17): a Phase III, open-label, multicentre study. Lancet Oncol.17(10), 1409–1418 (2016).

- Byrd JC , FurmanRR, CoutreSEet al. Three-year follow-up of treatment-naive and previously treated patients with CLL and SLL receiving single-agent ibrutinib. Blood125(16), 2497–2506 (2015).

- O’Brien S , FurmanRR, CoutreSEet al. Ibrutinib as initial therapy for elderly patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia or small lymphocytic lymphoma: an open-label, multicentre, Phase Ib/II trial. Lancet Oncol.15(1), 48–58 (2014).

- Jones JA , RobakT, BrownJRet al. Efficacy and safety of idelalisib in combination with ofatumumab for previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: an open-label, randomised Phase III trial. Lancet Haematol.4(3), e114–e126 (2017).

- Zelenetz AD , BarrientosJC, BrownJRet al. Idelalisib or placebo in combination with bendamustine and rituximab in patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: interim results from a Phase III, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol.18(3), 297–311 (2017).

- O’Brien SM , LamannaN, KippsTJet al. A Phase II study of idelalisib plus rituximab in treatment-naive older patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood126(25), 2686–2694 (2015).

- Burger JA , KeatingMJ, WierdaWGet al. Safety and activity of ibrutinib plus rituximab for patients with high-risk chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a single-arm, Phase II study. Lancet Oncol.15(10), 1090–1099 (2014).

- Cory S , AdamsJM. The Bcl2 family: regulators of the cellular life-or-death switch. Nat. Rev. Cancer2(9), 647–656 (2002).

- Scarfo L , GhiaP. Reprogramming cell death: BCL2 family inhibition in hematological malignancies. Immunol. Lett.155(1–2), 36–39 (2013).

- Roberts AW , SeymourJF, BrownJRet al. Substantial susceptibility of chronic lymphocytic leukemia to BCL2 inhibition: results of a Phase I study of navitoclax in patients with relapsed or refractory disease. J. Clin. Oncol.30(5), 488–496 (2012).

- Souers AJ , LeversonJD, BoghaertERet al. ABT-199, a potent and selective BCL-2 inhibitor, achieves antitumor activity while sparing platelets. Nat. Med.19(2), 202–208 (2013).

- Fischer K , Al-SawafO, FinkAMet al. Venetoclax and obinutuzumab in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood129(19), 2702–2705 (2017).

- Roberts AW , StilgenbauerS, SeymourJF, HuangDC. Venetoclax in patients with previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia.Clin. Cancer Res.23(16), 4527–4533 (2017).

- Stilgenbauer S , EichhorstB, ScheteligJet al. Venetoclax in relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia with 17p deletion: a multicentre, open-label, Phase II study. Lancet Oncol.17(6), 768–778 (2016).

- Hallek M , ChesonBD, CatovskyDet al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a report from the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia updating the National Cancer Institute-Working Group 1996 guidelines. Blood111(12), 5446–5456 (2008).

- Hallek M , ChesonB, CatovskyDet al. Response assessment in chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated with novel agents causing an increase of peripheral blood lymphocytes. Blood doi:https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2007-06-093906 (2012).

- Burger JA , LiK, KeatingMet al. Functional evidence from deuterated water labeling that the Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib blocks leukemia cell proliferation and trafficking and promotes leukemia cell death in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia and small lymphocytic lymphoma. Blood124(21), 326 (2014).

- Davids MS , BrownJR. Targeting the B cell receptor pathway in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk. Lymphoma53(12), 2362–2370 (2012).

- Hoellenriegel J , MeadowsSA, SivinaMet al. The phosphoinositide 3′-kinase delta inhibitor, CAL-101, inhibits B-cell receptor signaling and chemokine networks in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood118(13), 3603–3612 (2011).

- Herman SE , GordonAL, HertleinEet al. Bruton tyrosine kinase represents a promising therapeutic target for treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia and is effectively targeted by PCI-32765. Blood117(23), 6287–6296 (2011).

- Dreger P , ScheteligJ, AndersenNet al. Managing high-risk CLL during transition to a new treatment era: stem cell transplantation or novel agents? Blood 124(26), 3841–3849 (2014).

- Sharman JP , CoutreSE, FurmanRRet al. Second interim analysis of a Phase III study of idelalisib (ZYDELIG®) plus rituximab (R) for relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL): efficacy analysis in patient subpopulations with del(17p) and other adverse prognostic factors. Blood124(21), 330 (2014).

- Woyach JA , FurmanRR, LiuTMet al. Resistance mechanisms for the Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib. N. Engl. J. Med.370(24), 2286–2294 (2014).

- Liu TM , WoyachJA, ZhongYet al. Hypermorphic mutation of phospholipase C, gamma2 acquired in ibrutinib-resistant CLL confers BTK independency upon B-cell receptor activation. Blood126(1), 61–68 (2015).

- Burger JA , LandauDA, Taylor-WeinerAet al. Clonal evolution in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia developing resistance to BTK inhibition. Nat. Commun.7, 11589 (2016).

- Landau DA , TauschE, Taylor-WeinerANet al. Mutations driving CLL and their evolution in progression and relapse. Nature526(7574), 525–530 (2015).

- Hallek M . Signaling the end of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: new frontline treatment strategies. Blood122(23), 3723–3724 (2013).

- Fischer K , CramerP, BuschRet al. Bendamustine in combination with rituximab for previously untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a multicenter Phase II trial of the German Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Study Group. J. Clin. Oncol.30(26), 3209–3216 (2012).

- Fischer K , CramerP, BuschRet al. Bendamustine combined with rituximab in patients with relapsed and/or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a multicenter Phase II trial of the German Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Study Group. J. Clin. Oncol.29(26), 3559–3566 (2011).

- Knauf WU , LissitchkovT, AldaoudAet al. Bendamustine compared with chlorambucil in previously untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: updated results of a randomized Phase III trial. Br. J. Haematol.159(1), 67–77 (2012).

- Hillmen P , FurmanR, CoutreSet al. Pre-treatment with idelalisib markedly reduces rituximab infusion-related reactions and infusion interruptions in patients with CLL. EHA Annual Meeting. Milan, Italy, 12–15 June 2014 ( Poster 236).

- Sehn LH , GoyA, OffnerFCet al. Randomized Phase II trial comparing obinutuzumab (GA101) with rituximab in patients with relapsed CD20+ indolent B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma: final analysis of the GAUSS study. J. Clin. Oncol.33(30), 3467–3474 (2015).

- Sehn LH , ChuaN, MayerJet al. Obinutuzumab plus bendamustine versus bendamustine monotherapy in patients with rituximab-refractory indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (GADOLIN): a randomised, controlled, open-label, multicentre, Phase III trial. Lancet Oncol.17(8), 1081–1093 (2016).

- Kluin-Nelemans HC , HosterE, HermineOet al. Treatment of older patients with mantle-cell lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med.367(6), 520–531 (2012).

- Flinn IW , RuppertAS, HarwinWet al. A Phase II study of two dose levels of ofatumumab induction followed by maintenance therapy in symptomatic, previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Am. J. Hematol.91(10), 1020–1025 (2016).

- Van Oers MH , KuliczkowskiK, SmolejLet al. Ofatumumab maintenance versus observation in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (PROLONG): an open-label, multicentre, randomised Phase III study. Lancet Oncol.16(13), 1370–1379 (2015).

- Bottcher S , StilgenbauerS, BuschRet al. Standardized MRD flow and ASO IGH RQ-PCR for MRD quantification in CLL patients after rituximab-containing immunochemotherapy: a comparative analysis. Leukemia23(11), 2007–2017 (2009).

- Bottcher S , RitgenM, FischerKet al. Minimal residual disease quantification is an independent predictor of progression-free and overall survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a multivariate analysis from the randomized GCLLSG CLL8 trial. J. Clin. Oncol.30(9), 980–988 (2012).

- Kovacs G , RobrechtS, FinkAMet al. Minimal residual disease assessment improves prediction of outcome in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who achieve partial response: comprehensive analysis of two Phase III studies of the German CLL study group. J. Clin. Oncol.34(31), 3758–3765 (2016).

- Bottcher S . Paving the road to MRD-guided treatment in CLL. Blood123(24), 3683–3684 (2014).

- Strati P , KeatingMJ, O’BrienSMet al. Eradication of bone marrow minimal residual disease may prompt early treatment discontinuation in CLL. Blood123(24), 3727–3732 (2014).

- von Tresckow J , CramerP, BahloJet al. CLL2-BIG – a novel treatment regimen of bendamustine followed by GA101 and ibrutinib followed by ibrutinib and GA101 maintenance in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL): interim results of a Phase II-trial. Blood126(23), 4151 (2015).

- Cramer P , von TresckowJ, BahloJet al. Low incidence of tumor lysis syndromes (TLS) and infusion related reactions (IRR) in the CLL2-BAG trial evaluating a sequential treatment of bendamustine (B), obinutuzumab (GA101, G) and venetoclax (ABT-199, A) in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL): interim safety results of a Phase-II-trial of the German CLL study group (GCLLSG). Blood126(24), 2646–2659 (2016).

- von Tresckow J , CramerP, BahloJet al. CLL2-BIG – a novel treatment regimen of bendamustine followed by GA101 and ibrutinib followed by ibrutinib and GA101 maintenance in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL): results of a Phase II-trial. Blood126(23), 4151 (2016).