Abstract

Aim: To examine the effectiveness of eribulin mesylate for metastatic breast cancer post cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor (CDKi) 4/6 therapy. Materials&methods: US community oncologists reviewed charts of patients who had received eribulin from 3 February 2015 to 31 December 2017 after prior CDKi 4/6 therapy and detailed their clinical/treatment history, clinical outcomes (lesion measurements, progression, death) and toxicity. Results: Four patient cohorts were created according to eribulin line of therapy: second line, third line, per US label and fourth line with objective response rates/clinical benefit rates of 42.2%/58.7%, 26.1%/42.3%, 26.7%/54.1% and 17.9%/46.4%, respectively. Median progression-free survival/6-month progression-free survival (79.5% of all patients censored) by cohort was: 9.7 months/77.3%, 10.3 months/71.3%, not reached/70.4% and 4.0 months/0.0%, respectively. Overall occurrence of neutropenia = 23.5%, febrile neutropenia = 1.3%, peripheral neuropathy = 10.1% and diarrhea = 11.1%. Conclusion: Clinical outcome and adverse event rates were similar to those in clinical trials and other observational studies. Longer follow-up is required to confirm these findings.

Annually in the USA >250,000 women are diagnosed with invasive breast cancer (BC) [Citation1]. The most recent estimated prevalence (2016) of BC in USA was 3.5 million patients, of which approximately 140,000–150,000 are living with metastatic disease [Citation2,Citation3]. The majority of these women with metastatic BC (mBC) have hormone receptor positive (HR+), HER2- disease (60–70%) [Citation4,Citation5]. In 2015, palbociclib, a cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor (CDK 4/6i), became the first CDK4/6i approved for treatment of HR+/HER2- mBC in conjunction with letrozole. CDK 4/6i therapy with palbociclib, and subsequently ribociclib and abemaciclib, with a standard endocrine therapy backbone, quickly became the preferred first-line treatment for most patients with HR+/HER2- mBC. According to data published by the manufacturer of palbociclib (Pfizer), by January 2018, palbociclib had been prescribed for over 75,000 patients in the USA [Citation6].

While CDK 4/6i therapy adds another weapon into the armamentarium for clinicians treating patients with mBC, it has not eliminated the need for chemotherapy. An analysis of recent treatment patterns post-CDK 4/6i found 35.6% of regimens immediately following discontinuation of first-line CDK 4/6i therapy were chemotherapy [Citation7]. While sequential single-agent chemotherapy is the preferred and recommended approach for treating HR+/HER2- patients with disease progression following development of endocrine resistance [Citation8,Citation9], there is a lack of evidence describing the safety and effectiveness of these agents when used post CDK 4/6i. The only known real-world study exploring post-palbociclib treatment patterns found capecitabine and combination exemestane plus everolimus were most commonly prescribed. Effectiveness was not evaluated and as neutropenia is the dose-limiting toxicity of CDK 4/6i therapies we sought to evaluate its impact on subsequent chemotherapy [Citation10].

Eribulin mesylate (eribulin) is one of the several single-agent chemotherapeutics recommended and commonly used as palliative therapy for mBC patients and is approved in the USA for patients who received at least two prior chemotherapy regimens in the metastatic setting, including an anthracycline and a taxane in either the metastatic or adjuvant setting. This approval was based on findings from the EMBRACE trial in which eribulin significantly improved survival by 2.5 months over treatment with physician’s choice in women treated with two to five prior lines of therapy [Citation11]. To our knowledge, only two observational studies have reported the safety and effectiveness of eribulin specifically for real-world HR+/HER2- patients; both were conducted outside the USA, and neither discussed eribulin in the context of a post-CDK 4/6i therapy. We therefore conducted a retrospective observational study to examine safety and effectiveness of eribulin following prior CDK 4/6i therapy.

Methods

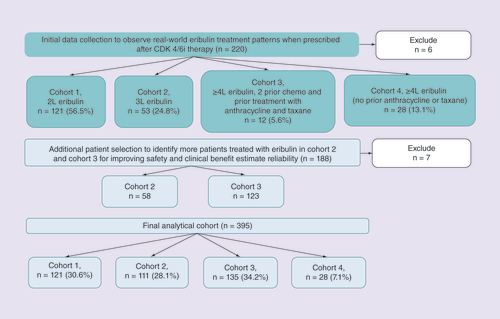

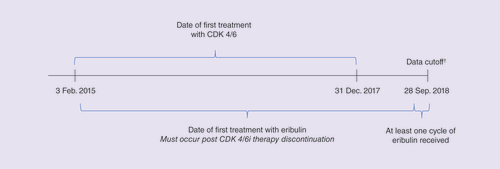

Data on utilization and outcomes of eribulin post CDK 4/6i were collected through a multisite chart review. Prior to chart data abstraction, the research protocol and electronic case report (eCRF) form were approved by Western Institutional Review Board. Providers from the Cardinal Health Oncology Provider Extended Network selected patients whose care they personally managed and who met the following criteria: diagnosis of HR+/HER2- mBC; treated with any CDK 4/6i between 3 February 2015 and 31 December 2017 (); received at least one injection of eribulin after CDK 4/6i; ≥18 years of age at the time eribulin initiation; date of initial BC diagnosis as well as receipt of neo/adjuvant treatment known to provider. Providers excluded patients who had received any adjuvant CDK 4/6i, received more than one CDK 4/6i therapy, received CDK 4/6i as part of an interventional clinical trial, or who had received any HER2-targeted therapy at any time. Data collection began 6 July 2018 and completed on 28 September 2018. Providers selected a maximum of 20 patients meeting the criteria and were instructed to first select the earliest eligible and then consecutive patients. Due to the selection criteria, which were necessary to achieve the research objectives, the selected patients were more likely to have discontinued CDK 4/6i prior to reaching the median progression-free survival (PFS) observed in their respective trials. The patient identification method used by providers may have led to selection of patients not representative of all patients qualified for chart abstraction and may lead to biases such as a higher proportion of de novo metastatic patients compared with known disease epidemiology.

†Patients may have still been receiving eribulin at the time of data cutoff.

We anticipated that eribulin might have been utilized both within and outside the US labeled indication. As such, we established sampling quotas reflective of the expected scenarios. Of the preplanned recruitment of 400 patients we sought – 150 patients who had received eribulin per the FDA-approved label, 150 patients who had received eribulin as third-line (3L) therapy and 100 patients who did not receive eribulin as per the US label or in third line (i.e., ‘other’). Providers were not informed of these classifications and input data on characteristics, treatment patterns and outcomes directly into the eCRF. The eCRF was constructed with skip logic allowing providers to only input necessary data (e.g., if provider indicated that patient was ‘Stage IV at initial diagnosis’ no data on the use of adjuvant therapy were collected). Data collection was paused after approximately a half of 400 eCRFs had been completed to conduct quality control of the submitted cases (systematic review of submitted eCRFs by clinical personnel and random validation of 10% of submitted charts) and describe real-world eribulin utilization patterns. After assigning all cases to the cohorts of interest (per US label, 3L, other) we split the ‘other’ cohort into two groups: second-line (2L) eribulin (directly following discontinuation of CDK 4/6i) and eribulin after at least three prior regimens but with a prior anthracycline and a taxane. This resulted in four eribulin analysis cohorts: Cohort 1 = 2L, Cohort 2 = 3L, Cohort 3 = per US label and Cohort 4 = fourth line or later without prior exposure to both an anthracycline and a taxane.

To measure the safety of eribulin post CDK 4/6i, providers were asked if during treatment with eribulin a patient had experienced any neutropenia, febrile neutropenia, peripheral neuropathy or diarrhea, and the highest grade of the event (e.g., ‘Which of the following, if any, did the patient experience during treatment with eribulin – neutropenia, febrile neutropenia, peripheral neuropathy, diarrhea, none’ and ‘What was the highest grade of [selected toxicity] experienced by the patient during treatment with eribulin – Grade 1, Grade 2, Grade 3, Grade 4’). Objective response rate (ORR), clinical benefit rate (CBR) and PFS were measured to assess clinical effectiveness. To determine ORR retrospectively, providers abstracted the diameters of all lesion sites (up to 2 per metastatic site) at the time of initiation of eribulin and subsequently at the time of best response to eribulin (providers indicated the date of the scan on which response determination was made) and to document if any new lesions had developed. RECIST v1.1 criteria [Citation12] were applied to these data to assign response levels: complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD) and progressive disease (PD) [Citation13,Citation14]. Providers were also able to indicate if response had not yet been evaluated (NE). The ORR was: (CR+PR)/(SD+PD+NE). The CBR was: (CR+PR+SD)/(PD+NE). Stable disease lasting 6 months or more was not considered due to variable follow-up. To measure PFS, providers were asked to record if the patient discontinued eribulin, if that discontinuation was due to disease progression or death (versus toxicity, patient request, financial challenges and scheduled duration of therapy completed), and the date on which the patient had progressed. PFS was calculated using Kaplan–Meier method; patients who were still receiving eribulin at data cutoff, and those who discontinued eribulin for reasons other than death or progression, were censored on the last date the provider had follow-up with the patient.

Results

Providers submitted 408 eCRFs of which 395 (96.8%) were retained after systematic and random quality assessment validation (). As planned, data collection was suspended after 220 eCRFs had been submitted, of which 214 records (97.3%) were retained. With the high utilization of eribulin in 2L (cohort 1), no further recruitment was conducted and the remaining quotas were filled in cohorts 3 and 4 (). The final sample included: cohort 1Â =Â 121 (30.6%), cohort 2Â =Â 111 (28.1%), cohort 3Â =Â 135 (34.2%) and cohort 4Â =Â 28 (7.1%).

The majority of patients were white/Caucasian (65.3%) followed by black/African–American (24.6%), Asian (7.1%) and other (3.3%); 63.5% had de novo metastatic disease; and 69.6% had visceral disease at diagnosis of mBC (). Overall, the majority of patients received palbociclib as their CDK 4/6i therapy (88.4%, ), which included 189 patients receiving palbociclib in combination with letrozole (47.9%), 116 in combination with fulvestrant (29.4%) and 44 in combination with exemestane or anastrozole (11.1%). The mean and median duration of CDK 4/6i therapy was 11 and 9.7 months, respectively, with 87.9% of CDK 4/6i therapy discontinuation due to disease progression. CDK 4/6i therapy was the initial treatment in the metastatic setting for all patients in cohort 1 (by definition), 73.0% of cohort 2, 50.4% of cohort 3 and 46.4% of cohort 4 (). The mean length of follow-up from initiation of first-line treatment was 28.8 months (). At the time of eribulin initiation, mean age of patients was 64.8 years, 89.6% of patients had visceral metastatic disease, and 23.0% of patients were Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG-PS) ≥2 (). The most common sites of metastases were bone (62.8%), lung (54.4%) and liver (47.1%) ().

Table 1. Demographics and clinical characteristics at metastatic breast cancer diagnosis, and cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor utilization.

Table 2. Patient characteristics at the initiation of eribulin.

Overall, 242 (62.3%) patients were still receiving eribulin at the time of data cutoff and 15.2% (n = 60) of patients were deceased (). Among 149 patients who discontinued eribulin, 51.7% (n = 77) discontinued due to disease progression, 20.8% (n = 31) due to patient request, 4.0% (n = 6) due to toxicity, 10.8% due to other reasons (n = 16, scheduled duration of therapy completed per provider report, patient financial challenges, death) and 12.7% for which the discontinuation rationale was unknown (n = 19). The median duration of eribulin treatment (among those who had discontinued therapy) was 3.7 months overall, ranging from 3.3 (cohort 4) to 5.5 months (cohort 1). Disease response to eribulin was unknown or too early to tell for 38.7% of patients, including 51.4% of cohort 2 and 35.6% of cohort 3 (). Overall, median time to response scan was 2.9 months. The ORR was consistent in cohorts 2 (26.1%) and 3 (26.7%), higher in cohort 1 (42.2%) and lowest in cohort 4 (17.9%). Median PFS (95% CI) and 6-month PFS rates are shown in . The CBR by cohort was: cohort 1 = 58.7%, cohort 2 = 42.3%, cohort 3 = 54.1% and cohort 4 = 46.4%. By cohort the median PFS/6-month PFS rates were: cohort 1 = 9.7 months/77.3%, cohort 2 = 10.3 months/71.3%, cohort 3 = not reached/70.4% and cohort 4 = 4.0 months/0.0%.

Table 3. Duration of eribulin treatment, rationale for discontinuation, objective disease response to eribulin and progression-free survival.

During eribulin treatment, 23.5% of patients were diagnosed with neutropenia; 1.3% with febrile neutropenia, 10.1% with peripheral neuropathy and 11.1% with diarrhea (). By cohort, the proportion of patients with neutropenia diagnosis ranged from 21.4% (cohort 4) to 26.1% (cohort 2). Grade 3/4 neutropenia was 34.4% of all neutropenia cases overall and ranged from 29.0% of cases in cohort 3 to 41.4% of cases in cohort 2. Overall, 12.2% of patients were prescribed a growth factor supportive care agent during eribulin treatment. Of the patients diagnosed with neutropenia, 58.1% had a previous neutropenia diagnosis in the 3Â months prior to the initiation of eribulin.

Table 4. Occurrence of selected toxicities during eribulin treatment.Table Footnoteâ€

Discussion

As we surpass 4Â years since the time of the initial approval of the first CDK 4/6i therapy we sought to evaluate how a specific agent, eribulin mesylate, is utilized in this new era of care and how, if at all, the safety and effectiveness of eribulin is similar or different from the clinical trial experience that predated CDK 4/6i. Overall we observed that eribulin appeared to be well-tolerated, with few treatment-related discontinuations observed in this study, and to provide a clinical benefit, which was not less than that observed in the pivotal trials when used at diverse points in the treatment pathway.

We acknowledge that the characteristics of the patient population deviate from the known BC epidemiology (e.g., 63% of patients were stage IV at diagnosis) and the characteristics of patients in the pivotal trials of the CDK 4/6i therapies (e.g., mean duration of CDK 4/6i therapy in our study of 11 months). While this study represents a specifically selected group of eribulin-treated patients, the results are consistent with other prior observational research conducted outside of the US. In studies of eribulin use in patients with two to four lines of prior therapy [Citation15–17], the ORR ranged from 21.1 [Citation15] to 32.0% [Citation16], rates of neutropenia ranged from 6.8 [Citation16] to 28.6% [Citation15] (with approximately half of cases grade 3/4) and peripheral neurotoxicity was observed in 35.3% patients [Citation15]. Similar to these studies, we found the ORR was dependent upon the line of therapy in which eribulin was administered. For patients receiving eribulin in 2L, a setting which has not been studied in other observational analysis, observed ORR was 42.2%.

While we attempted to measure PFS, the data are immature to draw any substantial conclusions. Overall, 314/395 patients were censored at the time of data cutoff. This did not allow estimation of the median PFS in cohort 3 and likely lead to overestimation of the median PFS of cohorts 1 and 2 [Citation18]. In two studies (from Italy and Japan), the observed median PFS estimates were approximately 3.0–4.7 months, which is substantially shorter than our estimates but consistent with that observed in pivotal eribulin trial (EMBACE) [Citation15,Citation17]. In comparison to EMBRACE1, our cohort was older (64.8 vs 55.0), more frequently nonwhite (35.0 vs 7.0%), included higher proportion of de novo metastatic patients (63.5 vs 15.9%) and patients with ECOG-PS ≥2 (23.0 vs 8.0%) [Citation11]. In EMBRACE, among heavily pretreated patients the ORR was 12.0% compared with 26.7% in our cohort 3 [Citation11]. In a separate Phase III trial of eribulin compared with capecitabine, in which 71.4% of patients had none or one prior therapy, the ORR by independent review was 16.6% [Citation19]. However, no direct statistical comparison to these data was performed.

While informative censoring biases the median PFS estimates in cohorts 1, 2 and 3, 15 events (53.6% event rate) were observed in cohort 4 (n = 28). Median PFS in cohort 4 was 4.0 months (95% CI: 3.2–4.4), similar to that reported in EMBRACE (median PFS of 3.7 months), which was conducted in a fairly comparable population (to cohort 4) in terms of prior lines of therapy (two or more).

The observed clinical benefit of eribulin leads to several questions regarding patient experience with CDK 4/6i therapies. First, it appears that our study cohorts had a substantially shorter duration of CDK 4/6i therapy compared with the pivotal trials of the three CDK 4/6i agents used by patients in our study [Citation20]. We observed an approximate PFS (represented by the mean duration of treatment with CDK 4/6i in our analysis) of <1Â year with CDK 4/6i overall, compared with the 2Â years or more PFS reported in the registrational trials of palbociclib, ribociclib and abemaciclib [Citation20]. Additionally, 28.4% of our patients received CDK 4/6i in 2L or greater, which differs from the recommended use of CDK 4/6i therapy as initial endocrine-based treatment. Furthermore, in subgroup analyses presented in the CDK 4/6i registrational trials, there was a smaller magnitude of benefit for patients with visceral metastatic disease and patients older than 65Â years, which comprised the majority of our study cohort. Thus, our population is likely highly enriched for patients with endocrine therapy resistance given that many would have had to progress on hormone-based therapy to chemotherapy within the relative brief limits of the study period. While patients were required to be estrogen receptor positive or HR+, we did not request quantification of the magnitude of the positivity. Future studies with a study population more accurately matched to the trial populations are needed to investigate this hypothesis further.

There are several important limitations to this research. It must be again acknowledged that by design our population may be significantly different than the true real-world population of patients who receive eribulin because of the requirement that a patient must have discontinued CDK 4/6i and initiated eribulin during the study period. In fact, in the cases of cohorts 2 and 3, patients must also have failed other intermediary therapies within a maximum of 3 years. This likely explains the high proportion of 2L use we observed in our initial treatment patterns analysis and then also, while not the cause, results in a significant reduction in duration of CDK 4/6i therapy in the remaining cohorts. We also acknowledge that >60% of patients included were stage IV at the time of diagnosis, which deviates significantly from the BC epidemiology (∼6% de novo metastatic at diagnosis). This was driven in large part by the even higher rates of stage IV disease in cohort 1. This could be due to patient selection by providers, study design, which likely led to inclusion of higher proportion of patients with more aggressive cancer, or misinterpretation of the patient’s stage at initial diagnosis where providers may have considered the patients stage at the time of metastatic diagnosis.

Next, follow-up data are immature (75% of patients censored for PFS analysis overall; cohort 4 provides only reliable estimate) when compared with clinical trials but provide the most up-to-date evaluation possible of this important treatment paradigm. Future studies with extended follow-up are needed to reliably estimate the median PFS of cohorts 1, 2 and 3 as early censoring of patients at higher risk of discontinuation due to progression upwardly biases PFS estimates. In addition, rates of toxicities may be underestimated due to the high rate of censoring as additional toxicities may occur during further treatment with eribulin. Moreover, under-reporting of toxicities in real-world studies can occur if the toxicity was not definitively documented in the patient’s clinical progress notes. Finally, disease response was not available in 38.7% of patients. However, by including ‘too early to tell/not available’ in the denominator of this calculation we are providing a conservative estimate of ORR as any additional CRs/PRs would increase the ORR estimate.

This initial evaluation of the safety and effectiveness of eribulin may be important evidence for practicing clinicians when considering treatment options post CDK 4/6i. While longer term follow-up is required to confirm these findings, the results from this observational study were similar to those in the EMBRACE study and eribulin may be a potential treatment option following prior CDK 4/6i therapy.

Conclusion

This initial evaluation of effectiveness and safety of eribulin may be important evidence for practicing clinicians when considering treatment options post CDK 4/6i. We found that prior CDK 4/6i exposure did not appear to negatively impact eribulin activity, however, further follow-up is required. The observed objective response rate of 26.7% in cohort 3 (eribulin prescribed per US label) was more than double the observed objective response rate in the pivotal phase 3 trial of eribulin*. Rates of neutropenia and peripheral neuropathy (52% and 35%, respectively) did not exceed those observed in the EMBRACE trial. Further research with longer clinical follow-up is warranted to validate these findings but this initial evaluation demonstrates that eribulin may be a potential treatment option following prior CDK 4/6i therapy.

*No statistical comparison was performed

There are few reports from clinical trials or observational research that describe the safety, efficacy and effectiveness of palliative chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer when used after prior treatment with a cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 4/6 inhibitor such as palbociclib, ribociclib or abemaciclib.

This retrospective, observational study of female metastatic breast cancer patients examined the safety and clinical outcomes for patients receiving one such palliative agent, eribulin mesylate, after previous treatment with any CDK 4/6 inhibitor.

Patients from the US Community Oncology Practices meeting these criteria were identified by their treating provider who abstracted data from the patients’ electronic health record regarding clinical characteristics, treatment history, length of exposure to CDK 4/6 inhibitor therapy, toxicities during eribulin treatment (neutropenia, febrile neutropenia, peripheral neuropathy and diarrhea), lesion measurements from radiographic scans (to calculate disease response/clinical benefit rate via RECIST v1.1 guidelines), and dates of disease progression (to calculate progression-free survival) and death.

A total of 395 patients met the selection criteria who were categorized into cohorts according to the line of therapy during which eribulin was received: second line; third line; per US label; greater than or equal to fourth line.

The objective response rate/clinical benefit rates per cohort 1–4 were 42.2%/58.7%, 26.1%/42.3%, 26.7%/54.1% and 17.9%/46.4%, respectively.

At data cut-off 37.8% of patients had discontinued eribulin (median duration of eribulin = 3.7 months). Rationale for discontinuation: progression = 51.7%, patient request = 20.8%, toxicity = 4.0%, unknown = 10.7% and other = 10.8%.

The median progression-free survival/6-month progression-free survival rate per cohort: 9.7Â months/77.3%, 10.3Â months/71.3%, not estimable/70.4%, 4.0Â months/0.0% with 79.5% of patients censored overall.

Across all cohorts: neutropenia = 23.5%, febrile neutropenia = 1.3%, peripheral neuropathy = 10.1% and diarrhea = 11.1%.

While longer term follow-up is required to confirm these findings, the results from this observational study were similar to those in the EMBRACE study and the rates of selected adverse events (e.g., neutropenia) did not exceed those observed in either clinical trials or observational studies.

Financial &competing interests disclosure

This study was sponsored by Eisai, Inc., Woodcliff Lake, NJ, USA. S Mougalian received consultant fees from Eisai, Inc. and Celgene; travel reimbursement from Puma Biotechnology; and research funding from Genentech, Pfizer/National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Grant E Wang, K Alexis and R Knoth are formerly with Eisai, Inc. D Chatterjee is employed by Eisai, Inc. B Feinberg, D Nero, T Miller, D Liassou and J Kish are employed by Cardinal Health Specialty Solutions. The authors are fully responsible for all the content and editorial decisions. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Cancer Stat Facts . Female breast cancer. National Cancer Institute, MD, USA (2019). https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html

- Mariotto AB , EtzioniR, HurlbertM, PenberthyL, MayerM. Estimation of the number of women living with metastatic breast cancer in the United States.Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev.26, 809–815 (2017).

- Miller KD , SiegelRL, LinCCet al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016.CA Cancer J. Clin.66, 271–289 (2016).

- Howlader N , AltekruseSF, LiCIet al. US incidence of breast cancer subtypes defined by joint hormone receptor and HER2 status.J. Natl Cancer Inst.106(5), doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju055 (2014).

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Cancer Stat Facts . Female breast cancer subtypes. National Cancer Institute, MD, USA (2019). https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast-subtypes.html

- Pfizer . Ibrance (palbociclib) online material (2019). https://www.pfizerpro.com/product/ibrance?cbn=1-510216238:1-518669114#ref3

- Princic N , AizerA, TangDH, SmithDM, JohnsonW, BardiaA. Predictors of systemic therapy sequences following a CDK 4/6 inhibitor-based regimen in post-menopausal women with hormone receptor positive, HEGFR-2 negative metastatic breast cancer.Curr. Med. Res. Opin35(1), 73–80 (2018).

- Gennari A , StocklerM, PuntoniMet al. Duration of chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J. Clin. Oncol.29, 2144–2149 (2011).

- NCCN . NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology – breast cancer (NCCN Evidence Blocks), version 1.2018 (2018). https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast_blocks.pdf

- Xi J , OzaA, ThomasSet al. Retrospective analysis of treatment patterns and effectiveness of palbociclib and subsequent regimens in metastatic breast cancer.J. Natl Compr. Canc. Netw.17, 141–147 (2019).

- Cortes J , O’ShaughnessyJ, LoeschDet al. Eribulin monotherapy versus treatment of physician’s choice in patients with metastatic breast cancer (EMBRACE): a Phase III open-label randomised study.Lancet377, 914–923 (2011).

- Eisenhauer EA , TherasseP, BogaertsJet al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1).Eur. J. Cancer45, 228–247 (2009).

- Feinberg BA , BharmalM, KlinkAJ, NabhanC, PhatakH. Using response evaluation criteria in solid tumors in real-world evidence cancer research.Future Oncol.14, 2841–2848 (2018).

- Luke JJ , GhateSR, KishJet al. Targeted agents or immuno-oncology therapies as first-line therapy for BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma: a real-world study.Future Oncol.15(25), 2933–2942 (2019).

- Gamucci T , MichelottiA, PizzutiLet al. Eribulin mesylate in pretreated breast cancer patients: a multicenter retrospective observational study.J. Cancer5, 320–327 (2014).

- Pedersini R , VassalliL, ClapsMet al. Eribulin in heavily pretreated metastatic breast cancer patients in the real world: a retrospective study.Oncology94(Suppl. 1), 10–15 (2018).

- Tanaka T , UenoM, NakashimaYet al. Retrospective analysis of the efficacy and safety of eribulin therapy for metastatic breast cancer in daily practice.Thorac. Cancer8, 523–529 (2017).

- Campigotto F , WllerE. Impact of informative censoring on the Kaplan–Meier estimate of progression-free survival in Phase II clinical trials.J. Clin. Oncol.32, 3068–3074 (2014).

- Kaufman PA , AwadaA, TwelvesCet al. Phase III open-label randomized study of eribulin mesylate versus capecitabine in patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer previously treated with an anthracycline and a taxane.J. Clin. Oncol.33, 594–601 (2015).

- Eggersmann TK , DegenhardtT, GluzO, WuerstleinR, HarbeckN. CDK4/6 inhibitors expand the therapeutic options in breast cancer: palbociclib, ribociclib and abemaciclib.BioDrugs33, 125–135 (2019).