Abstract

Aim: We conducted this study to describe nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (nmCRPC) patient characteristics and treatment patterns in the US, Europe and Japan. Materials&methods: Descriptive analyses were conducted using the 2015–2017 Ipsos Global Oncology Monitor Database. Results: A total of 2065 (442 in the US, 509 in Europe and 1114 in Japan) patients (median age: 74–80 years; stage III at diagnosis: 38.5%; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group [ECOG] score ≤1: 79.4%; treated by urologist: 88.4%) were included in the analytic cohort. Luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonists and antiandrogens were the most commonly used first regimen treatments. With subsequent nmCRPC regimens their use decreased, while the use of chemotherapy, corticosteroids, androgen synthesis inhibitors and second-generation androgen receptor inhibitors increased. Conclusion: These data represent real-world treatment patterns in nmCRPC.

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in men, accounting for 19% of new cancer cases [Citation1]. The American Cancer Society estimates about 174,650 new cases of prostate cancer will be diagnosed in the US in 2019 and about 31,620 men will die from prostate cancer [Citation1]. While most cases of prostate cancer can be cured with localized treatment options, 20–30% of men experience a disease recurrence requiring systemic hormonal treatment with androgen-deprivation therapies (ADTs) [Citation2]. However, men with prostate cancer eventually stop responding to ADT (i.e., become refractory to hormonal treatments), leading to disease progression. Disease progression despite ADT treatment is defined as castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) [Citation3–5].

The goal of treating patients with nonmetastatic CRPC (nmCRPC) is to delay metastasis while maintaining the quality of patients’ survival [Citation6,Citation7]. nmCRPC treatment options have traditionally included first-generation androgen receptor inhibitors (FGARIs) or active surveillance [Citation8]. The recent US FDA approval of second-generation ARis (SGARIs) such as apalutamide (13 February 2018) and enzalutamide (13 July 2018) is expected to affect the treatment landscape for nmCRPC [Citation9]. These drugs have also now received approval from the EMA for treatment of nmCRPC patients [Citation10–13].

Overall, limited evidence exists regarding real-world treatment patterns for nmCRPC. A UK-based survey suggested that active monitoring was the most common choice of oncologists. Among patients with high risk (i.e., prostate-specific antigen doubling time [PSA-DT] <3 months), second-generation hormones were preferred over standard chemotherapy. Estrogens were the least preferred option [Citation14]. A 2013 analysis of IMS Oncology Analyzer data for patients with CRPC (not restricted to nmCRPC) in five European countries (UK, Germany, Spain, Italy and France) reported that the most common treatments immediately initiated after CRPC diagnosis were docetaxel (50.5% of cases) and single-agent ADTs (24.5% of cases). This study also indicated that 35% of patients received second treatment after docetaxel. As patients progressed through lines of treatment, docetaxel was supplanted by other chemotherapeutic agents. Third-line treatments were more varied, with patients receiving different chemotherapeutic agents and hormonal therapies [Citation15].

The objective of the current analysis was to describe recent nmCRPC patients’ clinical and demographic characteristics, physician characteristics and treatment patterns.

Materials&methods

Study design

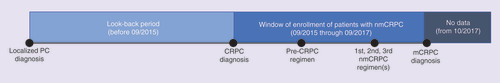

This retrospective database analysis of nmCRPC patients in the US, UK, France, Germany and Japan was conducted using quarterly cross-sectional data from the IPSOS Global Oncology Monitor database (GOMD). The study design is illustrated in . nmCRPC treatment information for each patient was only available during the study period (i.e., from September 2015 through September 2017). However, information on certain demographic and clinical characteristics (i.e., past smoking status, stage at prostate cancer diagnosis, co-morbid conditions) were available for each nmCRPC patient before September 2015. No follow-up data were available for any patient after October 2017.

Data source

The IPSOS GOMD is a large physician-based syndicated patient record database that can be used to identify treatments given to cancer patients. It contains data on patients from several countries, including the US, UK, France, Germany and Japan. Annually, approximately 1300 oncology physicians (representing over 105,000 patient cases) update case histories for approximately 5–30% of their currently treated patients for whom the responding physician is the primary decision maker. Most of the records are collected online and the remainder are collected via paper forms. The GOMD is validated with market-sizing studies every 2 years to ensure that the size and representativeness of its physician sample reflects the wider population of relevant treating physicians.

The GOMD has been used in several real-world treatment characterization studies [Citation16–19]. The database contains information about patient demographics (e.g., age and race), co-morbidities (e.g., hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, renal dysfunction, pulmonary disorder, thyroid disorder, dementia, depression, liver dysfunction) and treatments received, as well as demographic and practice characteristics for the treating physician. For each patient, the treatment received in the current regimen, most recent regimen, second most recent regimen and third most recent regimen are reported.

Patient population

The study sample included nmCRPC patients in the GOMD who were ≥18 years old at the time of prostate cancer diagnosis and received ≥1 nmCRPC treatment from September 2015 through September 2017. The sample excluded patients with a diagnosis of any other primary cancer during the study period. Ethical approval was not required for this study as IPSOS GOMD data are deidentified and anonymized and do not contain any patient identifiable information.

Outcomes

Demographics (e.g., age, race, smoking status) and clinical characteristics (e.g., stage at diagnosis, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group [ECOG] score, Gleason score, list of co-morbidities) of nmCRPC patients included in the analytic cohort were captured. Additionally, practice characteristics for the treating physician (e.g., specialty, location of practice, clinical trial participation) were also assessed. Finally, for each patient, the treatment received in the current regimen, most recent regimen, second most recent regimen and third most recent regimen are reported. For each regimen, the data include an indicator suggesting whether a patient was castrate-resistant (CR) at the time of receiving the treatment. This variable was used to determine each patient’s first, second and third nmCRPC regimen as well as the pre-CRPC regimen (i.e., the last hormone-sensitive treatment adjudicated by the treating physician before the patient received CR diagnosis). The first nmCRPC regimen was the first antineoplastic treatment used post-CR diagnosis.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted to establish patient and physician characteristics. For categorical (including dichotomous) end points, frequencies and percentages were reported. Continuous variables were summarized using mean, standard deviation, median and interquartile ranges.

To describe treatment patterns, the number of patients receiving monotherapy versus combination therapy, the proportion of patients receiving different classes of drugs and the top ten most commonly used drugs were determined for each nmCRPC regimen as well as the pre-CRPC regimen. Treatment patterns were described separately for each country in order to evaluate differences in practice patterns between countries.

Results

Patient&treating physician characteristics

A total of 2065 patients (442 in the US, 509 in Europe and 1114 in Japan) were treated for nmCRPC from September 2015 through September 2017. The median patient age across the five countries ranged from 74 to 80 years (). Of the 2065 included patients, 795 patients (38.5%) were diagnosed at stage III prostate cancer. Most patients had a moderate to high level of functioning, with a high proportion reporting an ECOG score of 0 (n = 990; 47.9%) or 1 (n = 650; 31.5%). Common co-morbidities included hypertension (n = 788; 38.2%), diabetes (n = 407; 19.7%) and cardiovascular disease (n = 387; 18.7%).

Patient demographics

Table 1. Nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer patient and treating physician characteristics by country.

Most treating physicians were urologists (n = 1825; 88.4%). Patients were largely treated in an office setting (n = 354; 80.1%) in the US, in a university hospital setting in Europe (n = 243; 47.7%) and general hospital in Japan (n = 862; 77.4%). Most responding physicians did not participate in any clinical trials (n = 1835; 88.86%).

Treatment patterns

United States

In the US, 442 patients received the first nmCRPC regimen. Information regarding second and third nmCRPC regimens was available for 42 (9.5%) and 22 (5.0%) patients, respectively. Information regarding pre-CRPC regimen was recorded for 130 (29.4%) patients.

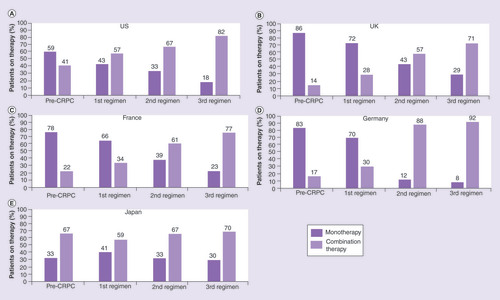

Most patients in the US were treated with monotherapy during the pre-CRPC regimen (n = 77; 59.2%) followed by the first nmCRPC regimen (n = 189; 42.8%) (). A greater proportion of US patients were treated with combination therapies in their second (n = 28; 66.7%) and third nmCRPC regimens (n = 18; 81.8%).

CRPC: Castration-resistant prostate cancer.

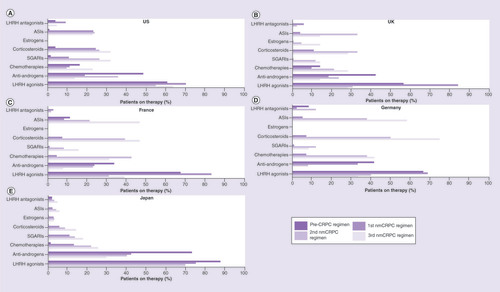

Across all four regimens, luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonists were the most common treatment choice in the US, followed by antiandrogens (). The number of patients treated with LHRH agonists decreased with subsequent regimens, whereas the use of SGARIs, chemotherapy and corticosteroids increased.

ASI: Androgen synthesis inhibitor; CRPC: Castration-resistant prostate cancer; LHRH: Luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone; nmCRPC: Nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer; SGARIs: Second-generation androgen receptor inhibitors.

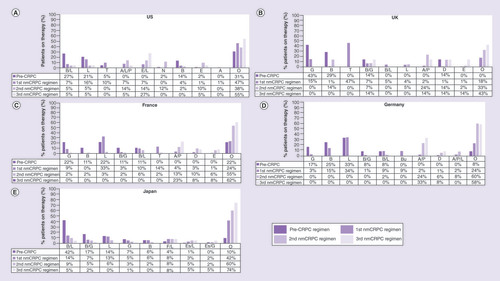

The top ten most commonly used drugs in each nmCRPC regimen as well as the pre-CRPC regimen are summarized in . The data present the nine most frequently used individual/combinations of drugs in each country and the ‘others’ category includes all other treatments that patients received collapsed into a single group. Leuprolide (n = 70; 16%) and triptorelin (n = 43; 10%) were the most commonly used first nmCRPC regimens in the US (). Abiraterone/leuprolide/prednisolone combination (n = 6; 14%) and enzalutamide/leuprolide combination (n = 6; 14%) were the most frequently used second nmCRPC regimens in the US, and enzalutamide/leuprolide combination (n = 6; 27%) was also the most frequently used third regimen. Bicalutamide/leuprolide combination (n = 35; 27%) and leuprolide monotherapy (n = 27; 21%) were the most frequently used hormone-sensitive treatments in the pre-CRPC regimen.

A: Abiraterone; A/L/P: Abiraterone/leuprolide/prednisolone; B: Bicalutamide; B/G: Bicalutamide/goserelin; B/L: Bicalutamide/leuprolide; Bu: Buserelin; CRPC: Castration-resistant prostate cancer; E: Enzalutamide; E/L: Enzalutamide/leuprolide; Es/G: Estramustin/goserelin; Es/L: Estramustine/leuprolide; F/L: Flutamide/leuprolide; G: Goserelin; L: Leuprolide; N: Nilutamide; nmCRPC: Nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer; T: Triptorelin; O: Others.

Europe

In Europe, 509 patients (173 in the UK, 111 France and 225 in Germany) received the first nmCRPC regimen. Of these, 42 (24.3%) and 7 (4.0%) patients in the UK, 62 (55.9%) and 13 (11.7%) patients in France, and 50 (22.2%) and 12 (5.3%) patients in Germany received second and third nmCRPC regimens, respectively. Information regarding pre-CRPC regimen was available for 7 (4.1%), 9 (8.1%) and 12 (5.3%) patients in the UK, France and Germany, respectively.

A majority of patients in Europe were treated with monotherapy during their pre-CRPC regimen (range: 77.8–85.7%) and first nmCRPC regimen (range: 65.8–71.7%) (–D). The proportions of patients treated with combination therapies were greater in the second (range: 57.1–88.0%) and third (range: 71.4–91.7%) nmCRPC regimens.

Similar to the US, most patients were treated with LHRH agonists (range: 68.9–85.0%), followed by antiandrogens (range: 18.5–33.3%) (–D) in the first nmCRPC regimen. The number of patients treated with LHRH agonists decreased while the use of chemotherapy, androgen synthesis inhibitors (ASIs) and corticosteroids increased with subsequent regimens.

The most commonly used first-regimen drugs were triptorelin (n = 81; 46.8%) and goserelin (n = 26; 15.0%) in the UK (); leuprolide (n = 37; 33.3%) and triptorelin (n = 15; 13.5%) in France (); and leuprolide (n = 77; 34.2%) and bicalutamide (n = 33; 14.7%) in Germany (). Combination of abiraterone/prednisolone was the most frequently used second nmCRPC regimen (range: 12.9–23.8%) and third nmCRPC regimen (range: 14.3–33.3%) across all three countries. Monotherapy with goserelin (range: 16.7–42.9%), leuprolide (range: 0.0–33.3%) and bicalutamide (range: 11.1–28.6%) were the most frequent hormone-sensitive treatments used in the pre-CRPC regimen. Drug use became more varied in nmCRPC subsequent regimens.

Japan

In Japan, 1114 patients received the first nmCRPC regimen. Of these, 587 (52.7%) and 297 (26.7%) patients received the second and third nmCRPC regimens.

A majority of patients in Japan (range: 58.7–70.0%) were treated with combination therapy irrespective of the regimen (), in contrast to the US and Europe, where a higher proportion of patients received monotherapy in the pre-CRPC and first nmCRPC regimens.

In terms of the drug classes used, LHRH agonists were used most frequently across all regimens (range: 69.2–86.4%), followed by antiandrogens (range: 29.3–72.5%) (). The use of SGARIs, chemotherapy and corticosteroids increased with later regimens.

The most commonly prescribed treatments were bicalutamide/leuprolide (n = 160; 14.4%) and leuprolide (n = 121; 12.7%) in the first nmCRPC regimen, bicalutamide/leuprolide (n = 55; 9.4%) and flutamide/leuprolide (n = 45; 7.7%) in the second nmCRPC regimen, and flutamide/leuprolide (n = 23; 7.8%) and estramustine/leuprolide (n = 15; 5.1%) in the third regimen ().

Discussion

This is the first real-world study to describe the characteristics and treatment patterns of patients with nmCRPC in the US, Europe and Japan who were treated from September 2015 through September 2017. The treatment of the prostate cancer continuum is rapidly changing, and therefore, this snapshot provides an important observation during a period in which FGARIs remained the mainstay of therapy in nmCRPC, yet SGARIs (albeit not approved) may have been used off-label. Several changes in guidelines specific to the treatment of nmCRPC patients were introduced in 2018, following the approval of enzalutamide and apalutamide in (high-risk) nmCRPC patients (PSA-DT <10 months). Therefore, this study, while not fully capturing the extent of changes in treatment patterns following the evolution of the treatment landscape and changes in treatment guidelines in 2018 (), captures a key time period in the lead-up to these changes and provides both interesting inter-regional/country observations and hypotheses for future real-world evidence in nmCRPC.

Table 2. Summary of nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer treatment guidelines.

Data from this analysis showed nmCRPC patients were elderly (median age: 74–80 years), were largely diagnosed at stage III and had a moderate to high level of functioning, perhaps reflecting the largely asymptomatic nature of nmCRPC. Most patients were treated by urologists.

Patients in the US, UK, France and Germany were largely treated with single agents in the initial regimens (i.e., pre-CRPC regimen, first nmCRPC regimen), with combination therapies used more frequently in subsequent nmCRPC regimens. In Japan, however, a majority of patients were treated with combination therapies across all regimens. LHRH agonists either alone or in combination with antiandrogens (known as combined androgen blockage [CAB]) were largely used for treatment as the first nmCRPC regimen. Therapies became more diverse in subsequent regimens with increased use of corticosteroids, chemotherapies, ASIs and SGARIs, with the use of SGARIs being the highest in the US.

The 2018 National Cancer Comprehensive Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend ‘observation without therapeutic intervention’ among patients with a PSA-DT ≥10 months or those who are frail and unlikely to benefit from treatment due to limited life expectancy [Citation20]. Active surveillance for low-risk patients with local disease is also recommended by the American Cancer Society, European Society of Medical Oncology and the Japanese Urological Association guidelines [Citation21–23]. The low rates of treatment utilization found in our analysis suggests that active surveillance is the preferred treatment approach. Given the study population characteristics, radical treatment may cause significant physical and psychological morbidities [Citation24] as well as toxicities. Considering the risk–benefit profile of the treatment options available during the study period, physicians may have expected that overtreating may not result in significant clinical benefit given that the study sample largely included elderly patients with significant co-morbidities or frailty [Citation25]. A previous survey of oncologists treating patients in the UK suggested that an active monitoring approach was preferred by up to 57% of surveyed oncologists, depending on the patient’s PSA level [Citation14]. It is important to note, however, that generalizing about physicians’ rationale for choosing ‘watchful waiting’ must be done with great caution, as the decision to maintain active surveillance depends on individual patient risk profiles (e.g., PSA-DT) that were not captured in the IPSOS GOMD dataset. However, the urgency to treat these patients may change with recently approved SGARi therapies. There appear to be differences between these newer treatments concerning adverse events of interest in nmCRPC, notably fatigue, cognitive problems, falls and fractures and skin rash [Citation26,Citation27]. A recent study of US oncologists and urologists treating nmCRPC patients found that clinicians were willing to trade substantial amounts of survival to avoid adverse events [Citation28]. Therefore, there remains a need for novel therapies with (more) favorable safety and tolerability profiles, which may minimize any adverse impact on patients’ daily lives, in this largely asymptomatic disease state.

In the current analysis, following the pre-CRPC regimen where patients were largely treated with hormonal therapies such as LHRH agonists, CAB (i.e., combination of LHRH agonists with antiandrogen therapy) was the most commonly used first nmCRPC regimen. This is in line with the 2018 NCCN guidelines, which recommend adding an antiandrogen (i.e., starting CAB) to help lower the testosterone level if the patient’s first hormonal therapy (i.e., pre-CRPC regimen) involved androgen deprivation using medical castration (i.e., treatment using LHRH agonists) [Citation20]. A cross-sectional analysis of European CRPC patients suggested that addition of antiandrogen therapy to a LHRH agonist (i.e., CAB) was the most commonly prescribed therapy when patients failed initial LHRH agonist therapy [Citation29]. A retrospective analysis of CRPC patient data from 2001 to 2007 in a large managed care claims database in the US showed LHRH agonists and antiandrogen therapies were the most common first-line hormone treatments [Citation30]. However, these analyses have focused on CRPC patients as a whole or on metastatic CRPC (mCRPC) populations. Previous literature has not specifically assessed nmCRPC patients as a separate cohort.

Data from our study suggest that the use of LHRH agonists and FGARIs declined in second or third nmCRPC regimens, whereas treatment with SGARIs, ASIs, corticosteroids and chemotherapy increased. These results are consistent with the 2018 NCCN guidelines. The NCCN guidelines also recommend adding SGARIs such as enzalutamide, apalutamide or ASIs (abiraterone plus prednisone) for patients with PSA-DT <10 months [Citation20], and the European Association of Urology guidelines recommend the use of SGARIs among high-risk nmCRPC patients as well [Citation31]. Although the Japanese Urological Association does not make specific treatment recommendations for nmCRPC patients, the guidelines recommend enzalutamide use among CRPC patients [Citation23]; this presumably is related to enzalutamide’s indication for mCRPC in Japan [Citation32]. A recent Japanese claims database analysis in CRPC patients reported results similar to the current analysis, where patients largely switched to abiraterone acetate in combination with either prednisone/prednisolone or enzalutamide after initial antiandrogen therapy failure [Citation33]. Our data also suggest that CAB treatment declined in subsequent nmCRPC regimens. This is clinically referred to as antiandrogen withdrawal and can be beneficial for several months, especially if the cancer cells were using antiandrogens for growth [Citation20]. Antiandrogen withdrawal among lower-risk nmCRPC patients is also recommended by the 2018 NCCN guidelines. Finally, we saw that the use of chemotherapy in subsequent regimens was lower in the US as compared with Europe or Japan. This pattern is consistent with the American Urological Association guidelines for nmCRPC patients, which recommend that clinicians should not offer systemic chemotherapy or immunotherapy to nmCRPC patients outside a clinical trial setting [Citation34]. A previous US-based study that utilized both a large claims database with electronic medical records confirmed a similar trend of decreasing docetaxel use and increasing use of SGARIs such as abiraterone and enzalutamide among mCRPC patients [Citation35]. A recent Japanese survey focusing on CRPC patients also indicated decreasing use of traditional chemotherapies such as docetaxel [Citation36].

Despite the NCCN, European Association of Urology and American Urological Association treatment guidelines consistently recommending the use of SGARIs (i.e., apalutamide and enzalutamide) and ASIs (i.e., abiraterone) among high-risk nmCRPC patients [Citation23,Citation31,Citation34], we found low use of these agents in our study population. Any use of these agents seen in the current analysis was restricted to second or third nmCRPC regimens. Key reasons for the relatively low SGARi use during our observation period are likely to be: new treatment guidelines being implemented in 2018; enzalutamide, apalutamide or darolutamide not having receive regulatory approval for use in nmCRPC patients until 2018 [Citation10,Citation11,Citation37–39]; and abiraterone not being indicated for use in nmCRPC.

The results of the current study must be interpreted in the light of certain limitations. First, the cross-sectional study design and the descriptive nature of the analysis preclude us from drawing any causal inferences. Second, the IPSOS GOMD data depend on physicians to assign CR status and report patient-/treatment-related details; in the absence of standardized diagnosis criteria, variability between physicians is possible. Third, patients could have been diagnosed with nmCRPC at any time during the study period, therefore the length of patient prognosis data after CRPC diagnosis is variable. Finally, IPSOS GOMD data did not include results from lab tests such as PSA values and PSA-DT. Despite these limitations, this dataset enabled assessment of treatment patterns in European countries and Japan, inclusive of Gleason score, ECOG score and PSA testing frequency, and thus provides an important addition to our current knowledge base of nmCRPC treatment patterns and conditions.

Conclusion

To the best our knowledge, this is the first study to describe patient and physician characteristics and treatment patterns in nmCRPC patients using a real-world dataset. The majority of the study population were elderly patients with a moderate to high level of functioning. About 88% of patients were treated by urologists. LHRH agonists combined with antiandrogens were the preferred therapy options for front-line nmCRPC treatment, indicating that hormonal therapies continue to be the mainstay of treatment for treating nmCRPC despite the introduction of guideline-recommended novel agents such as SGARIs. Patients were treated with more diverse regimens, including LHRH agonists/antagonists, SGARIs, ASIs, corticosteroids and chemotherapies, in subsequent nmCRPC regimens (time period 2015–2017). Novel nmCRPC therapies with more favorable safety and tolerability profiles may minimize any (additional) adverse impact on patients’ daily lives and provide an important addition to the treatment arsenal in this relatively asymptomatic disease state.

Future perspective

An update of the current analysis is recommended after more real-world data on SGARIs are available. Future studies should also assess the impact of these novel agents on overall survival, healthcare resource use, cost and quality of life.

The treatment goals for nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (nmCRPC) are to delay time to metastasis while maintaining the quality of a patient’s survival.

Treatment options for nmCRPC patients have traditionally included active surveillance or first-generation androgen receptor inhibitors (ARis) and more recently second-generation (SG) ARis (apalutamide, enzalutamide and darolutamide).

This study had three major objectives: to describe nmCRPC patients’ clinical and demographic characteristics, their physicians’ characteristics, and historical treatment patterns in the US, UK, Germany, France and Japan.

This study employed a retrospective, descriptive design and was conducted using the 2015–2017 IPSOS Global Oncology Monitor Database, a physician-extracted cross-sectional patient record dataset.

The study cohort included patients who received any treatment for nmCRPC.

This is the first real-world study to describe patient characteristics and treatment patterns in nmCRPC.

A total of 2065 patients (442 in the US, 509 in Europe and 1114 in Japan) were treated for nmCRPC from September 2015 through September 2017.

A plurality of patients (38.5%) were diagnosed at stage III prostate cancer and most reported an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group score of 0 (47.9%) or 1 (31.5%); the median age ranged from 74 to 80 years.

Patients in the US, UK, France and Germany were largely treated with single agents in the initial regimens (i.e., pre-CRPC regimen, first nmCRPC regimen), with combination therapies used more frequently in subsequent nmCRPC regimens.

In Japan, however, a majority of patients were treated with combination therapies across all regimens.

Luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonists either alone or in combination with antiandrogens were largely used for treatment as the first nmCRPC regimen; therapies became more diverse in subsequent regimens with increased use of corticosteroids, chemotherapies, androgen synthesis inhibitors and SGARIs.

The use of SGARIs was the highest in the US.

Future studies should evaluate utilization patterns after more experience with SGARIs has accumulated and explore any putative relationship between tolerable pharmacotherapy and extent of utilization.

Author contributions

The study was designed by R Shah, M Botteman and R Waldeck. The data were analyzed by R Shah. R Shah, M Botteman and R Waldeck contributed to the drafting of the manuscript.

Ethical conduct of research

Ethical approval was not required for this study as IPSOS GOMD data are deidentified and anonymized and do not contain any identifiable patient information.

Financial&competing interests disclosure

This research study was funded by Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals. R Shah and M Botteman are employees of Pharmerit International. M Botteman is also a shareholder of Pharmerit International. R Waldeck is an employee of Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals and owns Bayer equities-derived compensation. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

The authors acknowledge Rachel Shah (Pharmerit International) for providing medical writing support. This support was funded by Bayer.

Data sharing

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Cancer Society . Key statistics in prostate cancer (2019). https://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

- Mohler JL . The 2010 NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology on prostate cancer. J. Natl Compr. Canc. Netw.8(2), 162–200 (2010).

- Zhang TY , AgarwalN, SonpavdeG, DilorenzoG, BellmuntJ, VogelzangNJ. Management of castrate resistant prostate cancer – recent advances and optimal sequence of treatments. Curr. Urol. Rep.14(3), 174–183 (2013).

- Hotte SJ , SaadF. Current management of castrate-resistant prostate cancer. Curr. Oncol.17(Suppl. 2), S72 (2010).

- Kantoff PW , HiganoCS, ShoreNDet al. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med.363(5), 411–422 (2010).

- Tombal B . Non-metastatic CRPC and asymptomatic metastatic CRPC: which treatment for which patient?Ann. Oncol.23(Suppl. 10), x251–x258 (2012).

- Beaver JA , KluetzPG, PazdurR. Metastasis-free survival – a new end point in prostate cancer trials. N. Engl. J. Med.378(26), 2458–2460 (2018).

- Gillessen S , AttardG, BeerTMet al. Management of patients with advanced prostate cancer: the report of the Advanced Prostate Cancer Consensus Conference APCCC 2017. Eur. Urol.73(2), 178–211 (2018).

- Dall’era MA , AlbertsenPC, BangmaCet al. Active surveillance for prostate cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Eur. Urol.62(6), 976–983 (2012).

- European Society for Medical Oncology . FDA broadens approval for enzalutamide to include non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (2018). www.esmo.org/Oncology-News/FDA-Broadens-Approval-for-Enzalutamide-to-Include-Non-Metastatic-Castration-Resistant-Prostate-Cancer

- Astellas . Astellas receives european approval for XTANDI™ (enzalutamide) for adult men with high-risk non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (2018). www.astellas.com/en/news/14311

- Yamasaki M , YuasaT, YamamotoSet al. Efficacy and safety profile of enzalutamide for japanese patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer. Anticancer Res.36(1), 361–365 (2016).

- Johnson&Johnson . Janssen receives positive CHMP opinion for ERLEADA™ (apalutamide) for patients with non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer who are at high risk of developing metastatic disease (2018). www.jnj.com/janssen-receives-positive-chmp-opinion-for-erleada-apalutamide-for-patients-with-non-metastatic-castration-resistant-prostate-cancer-who-are-at-high-risk-of-developing-metastatic-disease

- Latif MF , TirmazySH, HussainSA, JacksonR, BarnettC, AzamF. Management of non metastatic castrate resistant prostate cancer (NM-CRPC), results of a UK wide national survey. J. Clin. Oncol.34(Suppl. 15), e16520–e16520 (2016).

- Pokras SM , ZyczynskiTM, LeesM, JiaoX, BlanchetteC, PowersJ. Treatment patterns after castration resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) diagnosis: a European physician survey. Value Health16(3), A1 (2013).

- Caldeira R , ScazafaveM. Real-world treatment patterns for hormone receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative advanced breast cancer in Europe and the United States. Oncol. Ther.4(2), 189–197 (2016).

- Varghese D , HillK, BottemanM. Functional status and associated treatment patterns among metastatic triple negative breast cancer (mTNBC) in EU 5. Eur. J. Cancer92, S118–S119 (2018).

- Karki C , PatelR, MartinoS, WriedeV, Shah-ManekB. Treatment pattern differences across the United States and EU5 among patients with ovarian cancer (2018). https://ascopubs.org/doi/abs/10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.e17516

- Ysebaert L , PhilipB, StilgenbauerS. Real-world treatment patterns of rituximab usage as single-agent therapy or part of combination regimens in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) in Eu5 countries (UK, France, Germany, Italy, and Spain). Value Health17(3), A234 (2014).

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Foundation . NCCN guidelines for patients 2018 – prostate cancer (2018). www.nccn.org/patients/guidelines/prostate/files/assets/common/downloads/files/prostate.pdf

- American Cancer Society . Watchful waiting or active surveillance for prostate cancer (2016). www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/treating/watchful-waiting.html

- Parker C , GillessenS, HeidenreichA, HorwichA, ESMO Guidelines Committee. Cancer of the prostate: ESMO clinical practice guidelines. Ann. Oncol.26(5), 69–77 (2015).

- Kakehi Y , SugimotoM, TaokaR, Committee for Establishment of the Evidenced-Based Clinical Practice Guideline for Prostate Cancer of the Japanese Urological Association. Evidenced-based clinical practice guideline for prostate cancer (summary: Japanese Urological Association, 2016 edition). Inter. J. Urol24(9), 648–666 (2017).

- Kinsella N , HellemanJ, BruinsmaSet al. Active surveillance for prostate cancer: a systematic review of contemporary worldwide practices. Transl. Androl. Urol.7(1), 83–97 (2018).

- American Cancer Society . Initial treatment of prostate vancer, by stage (2016). http://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/treating/by-stage.html

- Smith MR , SaadF, ChowdhurySet al. Apalutamide treatment and metastasis-free survival in prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med.378(15), 1408–1418 (2018).

- Hussain M , FizaziK, SaadFet al. Enzalutamide in men with nonmetastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med.378(26), 2465–2474 (2018).

- Srinivas S , MohamedAF, AppukkuttanSet al. Physician benefit-risk preferences for non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer treatment (nmCRPC). J. Clin. Oncol. (2019). https://ascopubs.org/doi/abs/10.1200/JCO.2019.37.15_suppl.e16610

- Sternberg CN , Baskin-BeyES, WatsonM, WorsfoldA, RiderA, TombalB. Treatment patterns and characteristics of European patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer. BMC Urol.13, 58 (2013).

- Engel-Nitz NM , AlemayehuB, ParryD, NathanF. Differences in treatment patterns among patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer treated by oncologists versus urologists in a US managed care population. Cancer Manag. Res.3, 233–245 (2011).

- Mateo J , FizaziK, GillessenSet al. Managing nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur. Urol.75(2), 285–293 (2018).

- Astellas . Astellas submits supplemental new drug application for approval of additional Indication of XTANDI® for the treatment of men with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer in Japan (2019). www.astellas.com/en/news/14851

- Cheung S , HamuroY, MahlichJ, NakayamaM, TsubotaA. Treatment pathways of Japanese prostate cancer patients – a retrospective transition analysis with administrative data. PLoS ONE13(4), e0195789 (2018).

- Lowrance WT , MuradMH, OhWK, JarrardDF, ResnickMJ, CooksonMS. Castration-resistant prostate cancer: AUA guideline amendment 2018. J. Urol.200(6), 1264–1272 (2018).

- Flaig TW , PotluriRC, NgY, ToddMB, MehraM. Treatment evolution for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer with recent introduction of novel agents: retrospective analysis of real-world data. Cancer Med.5(2), 182–191 (2016).

- Uemura H , DibonaventuraM, WangE, LedesmaDA, ConcialdiK, AitokuY. The treatment patterns of castration-resistant prostate cancer in Japan, including symptomatic skeletal events and associated treatment and healthcare resource use. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res.17(5), 511–517 (2017).

- US FDA . FDA approves apalutamide for non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (2018). www.fda.gov/Drugs/InformationOnDrugs/ApprovedDrugs/ucm596796.htm

- European Pharmaceutical Review . European Commission approves prostate cancer treatment Erleada (2019). www.europeanpharmaceuticalreview.com/news/83107/european-commission-prostate-cancer/

- Fizazi K , ShoreN, TammelaTLet al. Darolutamide in nonmetastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med.380(13), 1235–1246 (2019).