Abstract

Patients with advanced or metastatic gastric cancer often suffer from malnutrition, which can have an impact on quality of life, increase the toxicity of chemotherapy and reduce overall survival. Options available to the clinician to manage a patient’s nutritional status include screening and assessment of malnutrition at diagnosis, monitoring during the ‘cancer journey’, early detection of precachexia and the ongoing use of a multidisciplinary team (oncologists, other medical specialists and nutritionists). Because malnutrition is frequently overlooked and under treated in patients with advanced or metastatic gastric cancer, this narrative review focuses on the clinical meaning of nutritional status in gastric cancer and provides general guidance regarding nutritional care management for patients with advanced or metastatic gastric cancer.

Lay abstract

Patients with gastric cancer that has spread to other parts of the body often suffer from malnutrition. This can impact patients’ lives, increase side effects from cancer treatment and reduce life expectancy. This article provides guidance for healthcare providers on nutritional care for patients with gastric cancer. Key ways healthcare providers can contribute to nutritional care include: looking for malnutrition when a patient is diagnosed with gastric cancer; watching carefully for malnutrition during cancer treatment; keeping a lookout for early signs of extreme weight loss and muscle wasting; and involving a team of healthcare providers with a broad range of expertise in patients’ nutritional care.

Worldwide, gastric cancer is the fifth most frequently occurring cancer and the third leading cause of cancer-related death [Citation1]. In patients with unresectable advanced gastric cancer, chemotherapy is still the main treatment option, but has a poor survival outcome [Citation2,Citation3]. Medical teams caring for patients with gastric cancer usually focus on the administration of anticancer therapies: nevertheless, there is a growing interest in expanding this scope to include supportive care that may improve outcomes for these patients.

The prevalence of malnutrition is high in patients with cancer. According to the World Health Organization, malnutrition is defined as deficiencies, excesses or imbalances in a person’s intake of energy and/or nutrients [Citation4,Citation5]. It is estimated 40–80% of all cancer patients will become malnourished during the course of the disease, which can develop into cachexia due to complex interactions between pro-inflammatory cytokines and host metabolism [Citation6,Citation7]. Ultimately, cachexia is responsible for over 20% of all cancer-related deaths [Citation8]. The incidence of cancer rises dramatically as people age [Citation9], along with a greater risk of developing a poorer nutritional state leading to malnutrition [Citation1,Citation9]. However, resources available addressing this issue vary considerably, and many malnourished patients do not receive adequate nutritional care.

Malnutrition is particularly common in patients with gastric cancer because the cancer involves one of the primary digestive organs together with symptoms (such as nausea, vomiting, early satiety, loss of appetite and dysphagia following anticancer therapy), which lead to patients suffering poor intake and malabsorption of nutrients [Citation10,Citation11]. In one prospective, observational study conducted at 27 medical oncology centers including 1913 patients, those with gastroesophageal cancer had the highest frequency of malnutrition (48%) compared with other primary tumor types (malnutrition was reported for 36% of patients with head and neck cancer, 33% with lung cancer, 27% with hematological tumors and 24% with colorectal cancer) [Citation12]. Another retrospective cohort study showed the incidence of weight loss of >5%, or of weight loss of >2% with a BMI of <20 kg/m2, was 53% at 12 weeks after starting first-line chemotherapy and 88% after 48 weeks [Citation13]. Weight loss has also been reported as a prognostic factor for survival in patients with advanced gastric cancer receiving second-line chemotherapy [Citation14]. These findings underscore the critical importance of nutritional care management for patients with gastric cancer throughout their cancer journey.

Despite the recent development of improved treatments for gastric cancer, including antiangiogenic therapies and immunotherapy, nutritional care for gastric cancer lags substantially behind other cancer types. Furthermore, while many studies have investigated perioperative nutritional care for patients with gastric cancer who have undergone gastrectomy [Citation15,Citation16], there is limited literature regarding nutritional care for patients with advanced or metastatic gastric cancer. Therefore, the purpose of this narrative review is to describe the relevance of nutritional status in patients with advanced or metastatic gastric cancer and provide general guidance regarding management of their nutritional care.

Clinical relevance of nutritional status in patients with gastric cancer

Malnutrition is a prognostic factor of poor outcomes

Studies have revealed that poor nutritional status is an important negative prognostic factor for patients with advanced or metastatic gastric cancer [Citation17–20]. The Nutritional Risk Screening (NRS) 2002 is an assessment tool to evaluate nutritional risk [Citation17,Citation18]. A point value is assigned for 3 factors: impaired nutritional status 0 (absent) to 3 (severe); disease severity 0 (absent) to 3 (severe); and age 0 (<70 years) or 1 (≥70 years) with the total score ranging from 0 to 7 [Citation17,Citation19]. A large-scale cohort study indicated the NRS 2002 scale was an independent prognostic factor for survival outcomes for patients with metastatic gastric cancer [Citation17]. This study, which included 1664 patients with metastatic gastric cancer, showed that those with NRS 2002 >3 had shorter progression-free survival (PFS) (median PFS: 6.70 vs 7.70 months; p = 0.002) and overall survival (OS) (median OS: 9.03 vs 12.63 months; p < 0.001) than those with NRS 2002 ≤3 [Citation17]. Multivariate analysis by regrouping the results of the NRS 2002 scale to ≤3 or >3 demonstrated NRS was an independent prognostic factor for PFS (hazard ratio: 1.16; p = 0.028) and OS (hazard ratio: 1.29; p < 0.001) [Citation17]. Another study evaluated a prognostic model using inflammation- and nutrition-based scores in patients with metastatic gastric cancer treated with chemotherapy [Citation20]. Predictive factors were identified by multivariate analyses that demonstrated neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, modified Glasgow Prognostic Score and Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA) were independently related to patient survival [Citation20]. Based on their scores, patients were classified into favorable-, intermediate- and poor-risk groups [Citation20]. In the favorable-, intermediate- and poor-risk groups, the median OS was 27.6, 13.2 and 8.2 months, respectively, and the 2-year survival rates were 52, 16 and 3%, respectively (p < 0.001) [Citation20].

In 2016, the Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition proposed a two-step approach for diagnosing malnutrition that entailed: screening to identify at risk status and; assessing for diagnosis and grading the severity of malnutrition [Citation21]. One of the findings of this initiative was that weight loss and muscle loss were considered key phenotypic criteria for malnutrition [Citation21]. Another study examined body weight, inflammatory status and survival for 53 patients with histologically proven advanced gastric cancer who had started systemic chemotherapy and found 72% of patients exhibited weight loss during chemotherapy [Citation18]. Poorer mean OS and PFS were observed in patients with more weight loss (higher-than-average values) [Citation18]. An additional study evaluated Japanese patients with metastatic gastric cancer who had commenced first-line chemotherapy [Citation22]. Muscle loss during chemotherapy was defined as a ≥10% reduction in the skeletal muscle index [Citation22]. Of 118 patients, 89% had baseline sarcopenia and 31% developed muscle loss during chemotherapy [Citation22]. Muscle loss was significantly associated with shorter time to failure and OS, and it was an independent prognostic factor for both these parameters [Citation22].

Malnutrition is correlated with poor quality of life

Cancer and its accompanying treatments lead to biochemical and physiological changes linked to poorer quality of life (QoL) [Citation7]. Malnutrition in patients with gastric cancer can lead to changes in body composition and diminished mental and physical abilities [Citation23,Citation24]. Malnutrition, cachexia and sarcopenia, to some degree, all have a negative impact on the QoL of patients with gastric cancer [Citation9,Citation25–27]. In one analysis of nutritional status in hospitalized patients with malignant gastric, patient nutritional status was assessed using the PG-SGA, in which scores of 0–3 stand for well-nourished/suspicious malnutrition, 4–8 for moderate malnutrition and ≥9 for severe malnutrition. Furthermore, patient’s QoL was measured by a systematic evaluation approach, the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer quality of life questionnaire core 30 (QLQ-C30), which was developed by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer [Citation25]. This analysis included 2322 hospitalized patients with gastric cancer and the results showed patients with higher PG-SGA scores had functional categories and overall health status mean scores that were significantly lower, while the symptom categories were markedly increased compared with patients with lower PG-SGA scores (p < 0.001) indicating malnutrition was significantly correlated with worse QoL [Citation25].

Malnutrition increases the toxicity of chemotherapy

The dose of anticancer drugs is usually calculated based on patients’ body surface area or body weight without regard to any changes in body composition (e.g., proportions of muscle, fat and water) [Citation28–30]; yet, malnutrition can impact patients’ body composition resulting in an excess of toxicity from anticancer therapies and, consequently, a reduced dose of therapy or delayed treatment cycles.

In a study that evaluated weight loss and cachexia in 165 patients with gastric cancer, 73% (n = 121) of patients with cachexia had significantly decreased albumin, prealbumin and hemoglobin and received less chemotherapy due to hematological toxicity (p < 0.01) [Citation31]. Similar results were also observed in studies with other tumor types [Citation28,Citation32]. For instance, one study reported sarcopenia was significantly associated with severe chemotherapy toxicity in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer [Citation28]. Another study reported low lean body mass was a significant predictor of toxicity and neuropathy in colon cancer patients administered FOLFOX-containing regimens based on conventional body surface area dosing [Citation32].

Nutritional care may improve outcome

There is a paucity of prospective clinical studies exploring the efficacy of nutritional care in patients with advanced gastric cancer. One study evaluated whether nutritional care could prolong survival of patients with advanced gastric cancer [Citation33]. Nutritional care was prospectively provided to 347 patients with stage IV gastric cancer and NRS ≥3 [Citation33]. In the first 3 months, 59 patients (17%) experienced a shift in NRS to <3 [Citation33]. The proportion of patients with NRS <3 increased to 26% (90/347) after 6 months and then remained similar after 9 months (25%), 12 months (27%), 15 months (26%), 18 months (23%), 21 months (25%) and 24 months (25%) [Citation33]. Overall, 30% of patients demonstrated an NRS shift [Citation33]. Median survival was 14.3 months for all patients who experienced an NRS shift, whereas median survival for patients who maintained an NRS ≥3 was significantly less at 9.6 months (p = 0.001) [Citation33]. A multivariate analysis identified NRS shift, HER2 status, Lauren classification and chemotherapy response as independent prognostic factors [Citation33].

Building on these published studies, there are several ongoing studies that aim to evaluate the role of nutritional care in patients with advanced gastric cancer, for example, ‘An observational cohort study on the nutrition status of patients with advanced gastric cancer who received combination chemotherapy with ramucirumab and a taxane’ (UMIN ID: UMIN000037867) [Citation34] and ‘Early intravenous administration of nutritional support (IVANS) in metastatic gastric, cancer patients at nutritional risk undergoing first-line chemotherapy’ (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03949907).

Management of nutritional care in patients with gastric cancer

Currently, there is no specific nutritional care guidance for patients with gastric cancer; therefore general guidance should be followed [Citation35]. Malnutrition is often overlooked and undertreated in clinical practice despite being very common in gastric cancer and having a negative impact on patients. Below is practical guidance to help improve the provision of nutritional care.

Screening & assessment for malnutrition at baseline

All patients should be screened for malnutrition at the time of initial diagnosis of advanced or metastatic gastric cancer, and it should be determined whether there is a nutritional risk, such as weight loss, anorexia, sarcopenia or cachexia, low BMI and/or systemic inflammation. If the patient is found to be at risk, a full nutritional assessment should be conducted by a dietitian/nutritionist [Citation35–37]. These are very important approaches for early identification of malnutrition and ensuring timely medical intervention.

There are several validated nutritional screening/assessment tools, such as the NRS 2002, the PG-SGA and the Malnutrition Screening Tool, although none is gold standard [Citation38,Citation39]. NRS 2002 is one of the commonly used screening tools and uses a point system with high risk defined as NRS 2002 ≥3 and low risk defined as NRS 2002 <3 [Citation40]. The PG SGA is another frequently used nutrition assessment tool for patients with malignancies [Citation41,Citation42]. Furthermore, the PG SGA short form, also known as the abridged PG-SGA, is a potentially sensitive and malnutrition specific screening tool [Citation43].

Monitor nutritional status throughout the cancer journey

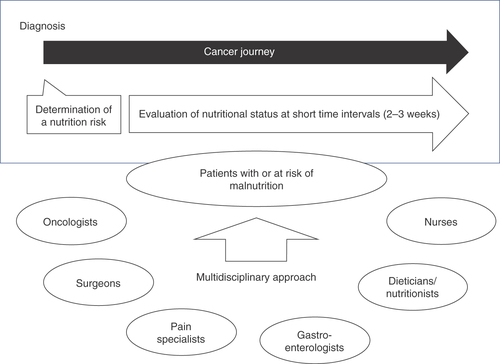

During the course of anticancer therapy, patients’ nutritional status often changes due to worsening of underlying disease and associated symptoms and/or toxicities induced by anticancer therapies. Therefore, evaluation of nutritional status should be performed on a regular basis and at short time intervals (2–3 weeks) throughout the whole ‘cancer journey’. Several questionnaires can be used for the monitoring of nutritional status, for example the NRS 2002 [Citation11,Citation44,Citation45].

For patients without malnutrition at baseline, this approach will help in the early identification of patients at risk of malnutrition and allow prompt treatment and/or careful follow-up. For patients with malnutrition and receiving nutritional care, monitoring the nutritional status will help with modifications to allow provision of the most appropriate nutritional care [Citation44].

Early identification of precachexia

Cancer cachexia ranges across three distinct stages related to the clinical severity of a patient’s condition. When patients are at a refractory stage of cachexia, cancer is not responsive to anticancer treatment and patients may survive less than 3 months [Citation29,Citation30]. Therefore, patients should be constantly monitored by nutritionists in parallel with oncologists, to diagnose metabolic modifications as early as possible, and thus allow preventive intervention [Citation46,Citation47].

A cachexia staging score was developed for use in patients with advanced cancer and has five components, each with its own score range: weight loss in the previous 6 months (0–3); completion of the simple questionnaire of sarcopenia to assess muscle function and sarcopenia (0–3); Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (0–2); loss of appetite (0–2); and abnormal biochemistry (0–2). The total of the scores is calculated, and scores ranging 0–2 classed as noncachexia, 3–4 as precachexia, 5–8 as cachexia and 9–12 as refractory cachexia [Citation48]. In an observational trial that included 297 patients with advanced cancer, 25% were classed as noncachexia, 24% as precachexia, 36% as cachexia and 7% as refractory cachexia [Citation48]. In this trial, the cachexia staging score allowed cachexia stages to be accurately classified, and cachexia to be identified and treated earlier [Citation48].

Multidisciplinary approach

To provide improved clinical outcomes for patients with cancer, a multidisciplinary team approach to nutritional care for patients is recommended [Citation49]. These teams can be composed of oncologists, other physicians (surgeons, pain specialists and gastroenterologists), dieticians/nutritionists, nurses and psychologists [Citation26,Citation29,Citation36,Citation37,Citation50]. Use of multidisciplinary teams are the benchmark of cancer care and result in improved patient outcomes [Citation49,Citation51,Citation52], which includes patients spending less time admitted to hospital [Citation35].

Multidisciplinary teams should regularly review the patient’s nutritional status for any changes and make adjustments when necessary [Citation36]. Ideally, the multidisciplinary team should become aware of metabolic problems early in the process and provide appropriate nutritional care [Citation36]. There is also evidence to suggest a multiprofessional nutritional steering group would benefit the patient [Citation23]. Nutritional steering groups may be known by several names, including a Nutritional Support Team and a Nutrition Steering Committee, and are composed of the patient and professionals specializing in food serving, food distribution, food preparation and selecting appropriates menus for the individual patient ( [Citation23] & ).

Table 1. Nutritional impairment scoring.

Conclusion

Malnutrition is very common in gastric cancer and it has negative impact on patients’ tolerance to anticancer therapy, QoL and OS. Nutritional screening and assessment at the time of initial diagnosis, continually monitoring nutritional status during the cancer journey and proactive intervention by a multidisciplinary team, can identify malnutrition early and allow provision of timely nutritional care, thereby enabling patients with gastric cancer to maintain their nutritional status and QoL and improve their cancer outcomes.

Future perspective

Malnutrition is very common in advanced or metastatic gastric cancer and has negative impacts on patients’ tolerance to anticancer therapy, QoL and OS. Despite its potential to contribute to poor prognosis in advanced or metastatic gastric cancer, malnutrition is usually overlooked in the clinic setting, relevant clinical research remains scarce and there is no globally accepted guidance. To achieve optimum outcomes in the future, it is likely that clinical research-driven and evidence-based guidelines will be widely used in clinical practice. Nutritional status will likely be routinely screened and assessed at that time of initial diagnosis and continually monitored throughout patients’ cancer journey. Furthermore, proactive intervention by a multidisciplinary team will become commonplace and allow early identification of malnutrition and timely nutritional care, thereby enabling maintenance of nutritional status, improved QoL and better prognosis for patients with advanced or metastatic gastric cancer.

Aim

This review focuses on the clinical meaning of nutritional status and provides general guidelines for management of nutritional care for patients with advanced or metastatic gastric cancer.

Background

The prevalence of malnutrition is high in patients with cancer, particularly in those with advanced or metastatic gastric cancer due to the involvement of the gut and associated poor intake and malabsorption of nutrients.

Poor nutritional status is a negative prognostic factor for advanced or metastatic gastric cancer and can result in excess toxicity from anticancer therapies and, consequently, reduced doses or delayed cycles of anticancer therapy.

Guidance for providing nutritional care

All patients should be screened for malnutrition at the time of initial diagnosis of advanced or metastatic gastric cancer. If a patient is found to be at risk, a full nutritional assessment should be conducted by a dietitian/nutritionist.

Several validated nutritional screening/assessment tools are available including the Nutrition Risk Screening 2002, the Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment and the Malnutrition Screening Tool, although none is gold standard.

During anticancer therapy, patients’ nutritional status often changes due to worsening of underlying disease and relevant symptoms and/or toxicities induced by anticancer therapies; evaluation of nutritional status should, therefore, be performed on a regular basis at short time intervals (every 2–3 weeks) throughout the patients’ cancer journeys.

Survival is poor for patients with refractory cachexia. Therefore, patients should be constantly monitored by dieticians/nutritionists in parallel with oncologists to diagnose metabolic changes early and allow preventive intervention.

To improve clinical outcomes for patients, a multidisciplinary team approach to nutritional care for patients is recommended, including oncologists, other physicians (surgeons, pain specialists and gastroenterologists), dieticians/nutritionists, nurses and psychologists. This group should regularly review patients’ nutritional status to identify metabolic changes early and manage with nutritional therapy.

Author contributions

T Mizukami contributed to the concept and design of the work, acquisition of the data, interpretation of the data and critical revision of the work for important intellectual content. Y Piao contributed to the concept of the work, acquisition of the data, interpretation of the data and critical revision of the work for important intellectual content.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This project was funded by Eli Lilly and Company. T Mizukami received grants and fees from Taiho Pharmaceutical, Eli Lilly Japan K.K., grants from Ono Pharmaceutical and personal fees from Sanofi, Asahi Kasei Pharmaceutical and Takeda. Y Piao is an employee of Eli Lilly and Company. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Medical writing support was provided by D Sherman and A Sakko, and editorial support was provided by D Schamberger of Syneos Health and funded by Eli Lilly and Company in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (www.ismpp.org/gpp3).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bray F , FerlayJ, SoerjomataramIet al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin.68(6), 394–424 (2018).

- Saito M , KiyozakiH, TakataOet al. Treatment of stage IV gastric cancer with induction chemotherapy using S-1 and cisplatin followed by curative resection in selected patients. World J. Surg. Oncol.12, 406 (2014).

- Koizumi W , NaraharaH, HaraTet al. Takeuchi, S-1 plus cisplatin versus S-1 alone for first-line treatment of advanced gastric cancer (SPIRITS trial): a Phase III trial. Lancet Oncol.9(3), 215–221 (2008).

- World Health Organization . Description of malnutrition. (2021). https://www.who.int/

- World Health Organization . Malnutrition. (2021). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malnutrition

- Vergara N , MontoyaJE, LunaHGet al. Quality of life and nutritional status among cancer patients on chemotherapy. Oman Med. J.28(4), 270–274 (2013).

- Marin Caro MM , LavianoA, PichardC. Nutritional intervention and quality of life in adult oncology patients. Clin. Nutr.26(3), 289–301 (2007).

- Lim S , BrownJL, WashingtonTAet al. Development and progression of cancer cachexia: perspectives from bench to bedside. Sports Medicine and Health Science2(4), 177–185 (2020).

- Mislang AR , DiDonato S, HubbardJet al. Nutritional management of older adults with gastrointestinal cancers: an International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) review paper. J. Geriatr. Oncol.9(4), 382–392 (2018).

- Merck Sharp & Dohme Manual Professional Version (2021). https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/digestive-disorders/tumors-of-the-digestive-system/stomach-cancer

- Rosania R , ChiapponiC, MalfertheinerPet al. Nutrition in patients with gastric cancer: an update. Gastrointest. Tumors2(4), 178–187 (2016).

- Marshall KM , LoeligerJ, NolteLet al. Prevalence of malnutrition and impact on clinical outcomes in cancer services: a comparison of two time points. Clin. Nutr.38(2), 644–651 (2019).

- Fukahori M , ShibataM, HamauchiSet al. A retrospective cohort study to investigate the incidence of cancer-related weight loss during chemotherapy in gastric cancer patients. Support. Care Cancer29(1), 341–348 (2021).

- Mizukami T , HamajiK, OnukiRet al. Impact of body weight loss on survival in patients with advanced gastric cancer receiving second-line treatment. Nutr. Cancerdoi: 10.1080/01635581.2021 (2021) ( Epub ahead of print).

- Aoyama T , NakazonoM, NagasawaS, SegamiK. Clinical impact of perioperative oral nutritional treatment for body composition changes in gastrointestinal cancer treatment. Anticancer Res.41(4), 1727–1732 (2021).

- Kubota T , ShodaK, KonishiHet al. Nutrition update in gastric cancer surgery. Ann. Gastroenterol. Surg.4(4), 360–368 (2020).

- Li YF , NieRC, WuTet al. Prognostic value of the nutritional risk screening 2002 scale in metastatic gastric cancer: a large-scale cohort study. J. Cancer10(1), 112–119 (2019).

- Takayoshi K , UchinoK, NakanoMet al. Weight loss during initial chemotherapy predicts survival in patients with advanced gastric cancer. Nutr. Cancer69(3), 408–415 (2017).

- Kondrup J , AllisonSP, EliaMet al. Clinical Practice Committee, N. Enteral, ESPEN guidelines for nutrition screening 2002. Clin. Nutr.22(4), 415–421 (2003).

- Hsieh MC , WangSH, ChuahSKet al. A prognostic model using inflammation- and nutrition-based scores in patients with metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma treated with chemotherapy. Medicine (Baltimore)95(17), e3504 (2016).

- Cederholm T , JensenGL, CorreiaMet al. GLIM criteria for the diagnosis of malnutrition – a consensus report from the global clinical nutrition community. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle10(1), 207–217 (2019).

- Sugiyama K , NaritaY, MitaniSet al. Baseline sarcopenia and skeletal muscle loss during chemotherapy affect survival outcomes in metastatic gastric cancer. Anticancer Res.38(10), 5859–5866 (2018).

- Reber E , StrahmR, BallyLet al. Efficacy and efficiency of nutritional support teams. J. Clin. Med.8(9), 1281 (2019).

- Gavazzi C , ColatruglioS, SironiAet al. Importance of early nutritional screening in patients with gastric cancer. Br. J. Nutr.106(12), 1773–1778 (2011).

- Guo ZQ , YuJM, LiWet al. Survey and analysis of the nutritional status in hospitalized patients with malignant gastric tumors and its influence on the quality of life. Support. Care Cancer28(1), 373–380 (2020).

- Ravasco P . Nutrition in cancer patients. J. Clin. Med.8(8), 1211 (2019).

- Palesty JA , DudrickSJ. What we have learned about cachexia in gastrointestinal cancer. Dig. Dis.21(3), 198–213 (2003).

- Barret M , AntounS, DalbanCet al. Sarcopenia is linked to treatment toxicity in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Nutr. Cancer66(4), 583–589 (2014).

- Bruggeman AR , KamalAH, LeBlancTWet al. Cancer cachexia: beyond weight loss. J. Oncol. Pract.12(11), 1163–1171 (2016).

- Barton MK . Cancer cachexia awareness, diagnosis, and treatment are lacking among oncology providers. CA Cancer J. Clin.67(2), 91–92 (2017).

- Li HL , LiuY, HuangDet al. The incidence and impact of weight loss with cachexia in gastric cancer patients. Presented at: American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting.IL, USA, (2020).

- Ali R , BaracosVE, SawyerMBet al. Lean body mass as an independent determinant of dose-limiting toxicity and neuropathy in patients with colon cancer treated with FOLFOX regimens. Cancer Med.5(4), 607–616 (2016).

- Qiu M , ZhouYX, JinYet al. Nutrition support can bring survival benefit to high nutrition risk gastric cancer patients who received chemotherapy. Support. Care Cancer23(7), 1933–1939 (2015).

- Mizukami T , MiyajiT, NaritaYet al. An observational study on nutrition status in gastric cancer patients receiving ramucirumab plus taxane: BALAST study. Future Oncol.doi: 10.2217/fon-2021-0076 (2021) ( Epub ahead of print).

- Choi WJ , KimJ. Nutritional care of gastric cancer patients with clinical outcomes and complications: a review. Clin. Nutr. Res.5(2), 65–78 (2016).

- Muscaritoli M , ArendsJ, AaproM. From guidelines to clinical practice: a roadmap for oncologists for nutrition therapy for cancer patients. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol.11, 1758835919880084 (2019).

- Virizuela JA , Camblor-AlvarezM, Luengo-PerezLMet al. Nutritional support and parenteral nutrition in cancer patients: an expert consensus report. Clin. Transl. Oncol.20(5), 619–629 (2018).

- Arends J . Struggling with nutrition in patients with advanced cancer: nutrition and nourishment-focusing on metabolism and supportive care. Ann. Oncol.29(Suppl. 2), ii27–ii34 (2018).

- Guo X , BianSB, PengZet al. Surgical selection and metastatic warning of splenic lymph node dissection in advanced gastric cancer radical surgery: a prospective, single-center, randomized controlled trial. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi23(2), 144–151 (2020).

- Kondrup J , RasmussenHH, HambergOet al. Nutritional risk screening (NRS 2002): a new method based on an analysis of controlled clinical trials. Clin. Nutr.22(3), 321–336 (2003).

- Bauer J , CapraS, FergusonM. Use of the scored Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA) as a nutrition assessment tool in patients with cancer. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr.56(8), 779–785 (2002).

- Gabrielson DK , ScaffidiD, LeungEet al. Use of an abridged scored Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (abPG-SGA) as a nutritional screening tool for cancer patients in an outpatient setting. Nutr. Cancer65(2), 234–239 (2013).

- Abbott J , TeleniL, McKavanaghDet al. Patient-generated subjective global assessment short form (PG-SGA SF) is a valid screening tool in chemotherapy outpatients. Support. Care Cancer24(9), 3883–3887 (2016).

- Santarpia L , ContaldoF, PasanisiF. Nutritional screening and early treatment of malnutrition in cancer patients. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle2(1), 27–35 (2011).

- Yalcin S , GumusM, OksuzogluBet al. Nutritional aspect of cancer care in medical oncology patients. Clin. Ther.41(11), 2382–2396 (2019).

- Fearon K , StrasserF, AnkerSDet al. Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: an international consensus. Lancet Oncol.12(5), 489–495 (2011).

- Diaz Garcia CV , AgullóOrtuño MT. Cachexia in cancer patients. Hos. Pal. Med. Int. J.1(1), 10–13 (2017).

- Zhou T , WangB, LiuHet al. Development and validation of a clinically applicable score to classify cachexia stages in advanced cancer patients. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle9(2), 306–314 (2018).

- Allum W , LordickF, AlsinaMet al. ECCO essential requirements for quality cancer care: oesophageal and gastric cancer. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol.122, 179–193 (2018).

- Arends J , BachmannP, BaracosVet al. ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in cancer patients. Clin. Nutr.36(1), 11–48 (2017).

- Prades J , RemueE, van HoofEet al. Is it worth reorganising cancer services on the basis of multidisciplinary teams (MDTs)? A systematic review of the objectives and organisation of MDTs and their impact on patient outcomes. Health Policy119(4), 464–474 (2015).

- Gullett NP , MazurakVC, HebbarGet al. Nutritional interventions for cancer-induced cachexia. Curr. Probl. Cancer35(2), 58–90 (2011).