Abstract

Aims: To characterize elderly large B-cell lymphoma patients who progress to second-line treatment to identify potential unmet treatment needs. Patients & methods: Retrospective USA cohort study, patients receiving second-line autologous stem cell transplant (SCT) preparative regimen (‘ASCT-intended’) versus those who did not; stratified further into those who received a stem cell transplant and those who did not. Primary outcomes were: healthcare resource utilization, costs and adverse events. Results: 1045 patients (22.0%) were included in the ASCT-intended group, 23.3% of whom received SCT (5.1% of entire second-line population). Non-SCT patients were older and had more comorbidities and generally higher rates of healthcare resource utilization and costs. Conclusion: Elderly second-line large B-cell lymphoma patients incurred substantial costs and a minority received potentially curative SCT, suggesting significant unmet need.

Lay abstract

Large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL) is an aggressive form of cancer. Although chemotherapy is often initially successful, LBCL recurs in about 50% of patients. For many years, the standard of care for recurrent LBCL has been a course of strong chemotherapy followed by stem cell transplant (SCT). However, many older patients cannot tolerate or do not respond well to chemotherapy and therefore cannot proceed to SCT. In this real-world study of Medicare patients, we found that only 5.1% of patients with recurrent LBCL ever received potentially curative SCT. They also had higher healthcare costs than similar patients who did receive SCT. This shows a significant unmet need in elderly LBCL patients that may potentially be addressed with recent treatment innovations.

Approximately 77,240 Americans were expected to be diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma in 2020 and an estimated one-third of these patients were diagnosed with the diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL) subtype [Citation1]. When diagnosed early (stage I/II), 5-year survival for diffuse LBCL is approximately 73%, but over half of patients are diagnosed at stage III or IV, where 5-year survival rates drop to 63.7 and 52.7%, respectively [Citation2]. Despite ongoing research into new treatment advances, age-adjusted death rates have been relatively stable in recent years (2009–2018) [Citation2].

Standard first line of therapy (LOT) for patients with LBCL involves chemotherapy with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (R-CHOP) given in four to six 21-day cycles or a similar regimen, such as R-CHOP with the addition of etoposide (R-EPOCH) [Citation3]. While many patients respond to these regimens, up to 50% relapse or fail to achieve remission [Citation4,Citation5]. For those patients, the goal of treatment with curative intent is stem cell transplant (SCT), and the standard course of treatment involves high-dose chemotherapy followed by SCT [Citation3]. However, evidence from clinical trials has shown that approximately half of all relapsed/refractory LBCL patients do not qualify for SCT due to age or comorbidities; of those who do qualify, another 50% never receive SCT because they do not respond to or cannot tolerate the preparatory chemotherapy regimens [Citation4–6].

These data from controlled studies imply that only approximately 25% of patients ultimately receive SCT, the standard of care for second-line treatment of LBCL. A recent real-world, claims-based study of a commercially-insured population yielded even lower estimates of the likelihood of receiving SCT. In that study, only 36.3% of patients qualified for SCT on the basis of receiving a standard SCT preparatory regimen, and of those, only 30.3% ultimately received a transplant [Citation7]. For patients who do not qualify for or cannot tolerate SCT, further treatment options are limited, and their prognosis has been poor, with median survival of less than 7 months [Citation4,Citation6].

The current real-world evidence describing treatment patterns and healthcare resource use among the group of LBCL patients who proceed to a second LOT with or without SCT is limited. In addition, existing studies tend to focus on commercially insured, working-age patients; given that the median age of LBCL patients at diagnosis is 66 years [Citation2], research involving elderly patients would advance the literature [Citation1,Citation8,Citation9]. Therefore the current study sought to better characterize the elderly LBCL population in the USA who progressed to a second LOT, by comparing the patient characteristics between those deemed eligible versus those who were ineligible for SCT, and comparing treatments, adverse events, healthcare resource utilization and costs between those who received a transplant and those who did not among those patients deemed eligible for SCT.

Patients & methods

Study design

This was a retrospective cohort study which used 100% Medicare Fee-for-Service (FFS) Parts A and B claims and Part D Prescriptions Drug Event data to identify patients 65 years of age and older who were newly diagnosed with LBCL during the identification period (between 1 July 2012 and 31 December 2017) and who received at least two LOTs. To be eligible for the study, patients must have had continuous enrollment in FFS A/B/D for at least 6 months prior (baseline) to the date of their first LBCL claim (diagnosis index date) and at least 12 months post-index (follow-up), or died after initiating a second LOT. Patients were considered for inclusion if they had at least two LBCL diagnoses at least 14 days apart using International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 9th or 10th Revision, Clinical Modification diagnosis codes (ICD9: 200.0*, 200.7*, 200.8*, 202.8*; ICD10: C83.3*, C85.1*, C85.8*, C83.8*, C83.9*).

Patients were required to receive a standard first LOT regimen per National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) B-cell lymphoma guidelines (CHOP or similar, with or without rituximab) [Citation3] as their first LOT and to have progressed to second LOT to be included in the study. The first LOT was defined as beginning with the date of initiation of chemotherapy as evidenced by an encounter with a Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System code or National Drug Code corresponding to an included drug. Regimens were determined to be all drugs received within 30 days of initiation. Any change made to the regimen within 30 days of initiation was considered a new LOT except for the addition or deletion of a single drug. Any gap in therapy greater than 60 days was considered as terminating the prior LOT even if the subsequent LOT was the same regimen.

NCCN B-cell lymphoma guidelines classify second or higher LOT regimens into two categories: those that indicate the patient is ‘intended for transplant’ versus all others, which NCCN consider ‘not intended for transplant’. The ‘intended for transplant’ category includes platinum-based regimens and MINE (mesna, ifosfamide, mitoxantrone and etoposide). Supplementary Table 1 gives a full description of first- and second-LOT regimens. Eligible patients who received a second or subsequent LOT with a SCT-preparative regimen per NCCN B-cell lymphoma guidelines were stratified into the ‘ASCT-intended’ cohort and the remainder were included in the ‘ASCT-not-intended’ cohort. We used the acronym ‘ASCT’ for the stratification into intended/not-intended cohorts to emphasize that the standard of care for these patients is autologous SCT; regardless of the type of SCT the patients ultimately received, or whether they received SCT at all, the intended form of SCT was assumed to be autologous.

It should be emphasized that the only criterion used to stratify patients into ASCT-intended versus ASCT-not-intended cohorts was the chemotherapeutic agents administered as reflected in their claims. The sole source of data for this study was Medicare FFS claims. Other treatment-related variables such as the dosages of the agents or a patient’s response to chemotherapy may be of clinical relevance but cannot be determined from claims. For example, the patient who receives an ASCT-intended LOT as second line or higher, but does not respond, may be considered ineligible for ASCT by their provider; but that patient will be classified as ASCT-intended in this study based solely on the receipt of their second-line regimen. Clinical response cannot be determined from claims. Furthermore, treatments for chemotherapy side effects, such as hematopoietic growth factors or anti-emetics, were assumed to be standard of care and therefore out of scope for this study.

The ASCT-intended group was further stratified into those who received SCT (either autologous or allogeneic) and those who did not receive SCT, labeled ‘SCT’ and ‘non-SCT’, respectively. These two subsets formed the primary comparison groups and were described and compared on all study measures; the ASCT-not-intended cohort was described with baseline characteristics only. SCT was identified using claims with an appropriate ICD-9/10 procedure or Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System code (Supplementary Table 2). In the event that a patient in the ASCT-not-intended group subsequently received a SCT, they were recoded to the SCT cohort and flagged as an exception. Patients who received a SCT prior to their second LOT were excluded from the study.

It should be reiterated that clinical considerations in whether or not to proceed to SCT, such as the patient’s response to chemotherapy or the presence of toxicities, are not available in this study, which is based solely on claims data. The splitting of the ASCT-intended cohort into SCT versus non-SCT groups was based solely on the presence or absence of claims for a transplant.

Measures

Baseline demographic information was collected at diagnosis index date and included age, gender, geographic region, race, dual eligibility status (Medicare and Medicaid) and original reason for Medicare eligibility (age or disability). Charlson–Deyo Comorbidity Index (CCI) [Citation10,Citation11] was calculated over the course of the baseline period. For patients in the SCT cohort, the type of SCT (autologous or allogeneic) was also recorded.

Treatment variables were assessed during the entire follow-up period from index date until loss to follow-up (death, disenrollment or the end of the study period), except where noted below, and consisted of:

Frequencies of observed regimens in first and second LOT;

Duration of first and second LOT;

Time from diagnosis to first and second LOT;

Time to relapse, defined as time from end of first LOT to initiation of second LOT;

Type of treatments received as third LOT and higher (maintenance therapy, LBCL-directed therapeutic therapy or no therapy).

The primary outcomes of healthcare resource utilization (HCRU), direct HCRU costs and adverse events (incidence and associated costs) were assessed over the follow-up period from initiation of second LOT until loss to follow-up (death, disenrollment or end of the study period). HCRU consisted of hospitalizations (incidence and length of stay), outpatient visits (including hospital outpatient department and physician office visits), emergency department (ED) visits and post-acute care (skilled nursing facility, hospice, home health agency). Because the groups differed on the duration of follow-up post-second LOT, the number of days or visits was reported as per 1000 patients per month (P1000PPM). Average length of stay was also reported for inpatient and skilled nursing facility as that is based on a patient stay and is independent of the duration of the observation period. Costs reflected the total allowed amount adjusted to 2019 US dollars using the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index and were reported as dollars per patient per month (PPPM). Costs were categorized as inpatient, ED, outpatient, all other medical, and Part D drugs.

Statistical analysis

Means, standard deviations and medians were reported for continuous variables, and frequency and percentages were reported for categorical variables. Summary statistics for all baseline characteristics were reported separately for all cohorts (ASCT-not-intended, ASCT-intended and received SCT, ASCT-intended and did not receive SCT). Detailed analyses for all other variables (HCRU, costs, adverse events) were stratified by the presence or absence of SCTs in the ASCT-intended cohort.

Standard inferential statistical tests are based on inferring from a sample to the population. This study was based on the entire 100% FFS population and therefore yields results that are actual population values rather than population estimates based on a sample. However, to facilitate interpretation of the observed differences between the SCT and non-SCT cohorts, p-values were reported using t-test for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables. All analyses and the generation of output were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 for Unix (SAS Institute, Inc., NC, USA).

Results

Study population

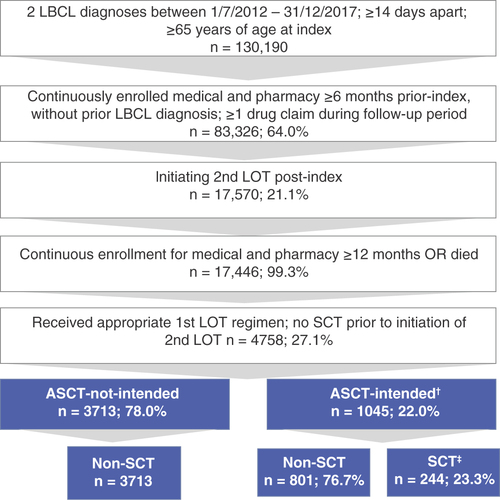

A total of 149,457 patients were identified with newly diagnosed LBCL during the identification period (1 July 2012 to 31 December 2017), 4758 of whom met all study inclusion criteria (). The majority of these patients (3713; 78%) did not receive a SCT-preparative regimen after their first LOT and made up the ASCT-not-intended group; the remaining patients (1045; 22%) constituted the ASCT-intended group and either received a SCT-preparative regimen or received a second LOT regimen which was not SCT-intended but subsequently received a SCT, and were therefore recoded into the ASCT-intended category (136; 13% of ASCT-intended). The ASCT-intended group was further divided into the primary comparator groups of patients who received a SCT (244; 23.3% – the ‘SCT’ group) and those who did not receive a SCT (801; 76.7% – the ‘non-SCT’ group). 199 patients (81.6%) received a SCT as their second line and 45 (18.4%) received it as third line or higher.

†136 patients (13%) were recoded from ASCT-not-intended to ASCT-intended because they received SCT during follow-up.

‡199 patients (81.6%) received SCT second line and 45 (18.4%) received SCT third line or higher.

ASCT: Autologous stem cell transplant; LOT: Line of therapy; SCT: Stem cell transplant.

summarizes patient characteristics. Median duration of follow-up (from diagnosis to death, disenrollment or the end of the study period) ranged from 272 to 1064 days, depending on cohort. ASCT-not-intended versus ASCT-intended patients overall had similar characteristics except that the former were 2 years older on average and more likely to be female. Within the ASCT-intended group, characteristics were also similar, but SCT patients were, on average, about 5 years younger (p < 0.001), slightly more likely to be male (p < 0.01) and had slightly lower mean CCI scores (p < 0.01). Of the non-SCT patients, 13.1% (105) were Dual Eligible versus 4.5% (11) of SCT patients (p < 0.001), indicating that lower-income patients were less likely to receive a SCT. ASCT was the most common type of SCT (n = 229; 93.9%) and no patient had more than one SCT during the follow-up period.

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

Treatment characteristics

As specified by the study inclusion criteria, all patients received a CHOP-like regimen, with or without rituximab, as their first LOT and proceeded to second LOT. Second-line regimens varied across the range of ASCT-intended regimens. The most common second-line regimen was gemcitabine and oxaliplatin (GemOx) plus rituximab (19.9%), followed by ifosfamide, carboplatin and etoposide (ICE) plus rituximab (10.1%). Treatment regimen distribution did not differ significantly between SCT and non-SCT cohorts.

Other treatment characteristics are summarized in . Duration of first LOT was the same for both ASCT-intended cohorts (approximately equal to five chemotherapy cycles). Duration of second LOT was shorter than that of first LOT for both groups and was significantly longer in non-SCT than SCT (~three vs two cycles, respectively). Although the reason for the shorter course of second-line treatment compared with the first cannot be determined from claims data, it can be hypothesized that treatment was terminated by the provider when it was determined to have been ineffective or poorly tolerated for the non-SCT group, or to have been a satisfactory response to proceed to SCT for the SCT group.

Table 2. Treatment characteristics.

The times from diagnosis to the initiation of both first and second LOTs were slightly longer for patients in the non-SCT group than in the SCT group, as was the time to relapse between the first and second LOTs (212 vs 200 days, respectively), although these differences did not reach statistical significance. Although overall survival was not an outcome of this study because of the non-equivalence of the groups, research has shown that ASCT-intended patients who have refractory disease or experience relapse within 12 months of first LOT have poorer survival versus patients relapsing after 12 months [Citation5]. Supplementary Figure 1 summarizes overall survival for the ASCT-intended patients, broken down by time to relapse.

Most patients in both groups did not receive a third or greater LOT (57.3% in the non-SCT group and 61.1% in the SCT group). However, a significantly higher proportion of patients in the non-SCT group received a therapeutic regimen rather than a maintenance regimen compared with the SCT group (38.7 vs 7%, respectively; p < 0.001).

Utilization & cost outcomes

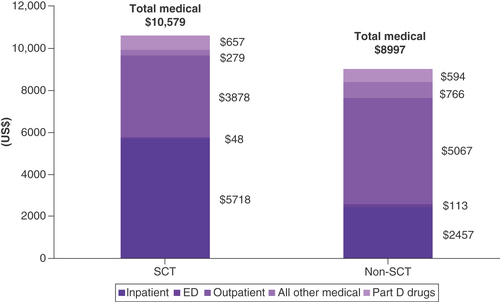

Costs and HCRU were calculated over the time period from initiation of second LOT until loss to follow-up and are summarized in & , respectively. Length of follow-up was approximately twice as long for the SCT patients as for non-SCT patients.

Table 3. Healthcare resource utilization, second line of treatment to end of follow-up.

ED: Emergency department; SCT: Stem cell transplant.

Non-SCT patients had higher all-cause HCRU versus SCT patients for all categories except hospitalizations (prevalence: 74.2 vs 99.6%; days P1000PPM: 906 vs 1498; average length of stay: 6.2 vs 12.6 days, respectively; ). It should be noted that inpatient utilization for the SCT cohort includes the SCT procedure itself, which took place in the inpatient setting for 94% of patients.

Although approximately half the patients in both groups had at least one ED visit, non-SCT patients had over twice as many ED visits on a P1000PPM basis than SCT (107.6 vs 49.6, respectively).

The groups had similar outpatient utilization, but non-SCT post-acute care utilization was materially higher than SCT for all utilization metrics.

Total all-cause costs were 17.6% higher in the SCT group versus the non-SCT group ($10,579 vs $8997 PPPM, respectively; ). These higher costs were primarily driven by inpatient hospitalization costs ($5718 PPPM in the SCT group vs $2457 in the non-SCT group), but pharmaceutical costs were also slightly higher ($657 PPPM in the SCT group vs $594 in the non-SCT group). As stated above, a certain proportion of the SCT group’s inpatient costs were for the SCT procedure itself, which the non-SCT group did not incur. If inpatient costs are factored out of both groups, post-second LOT costs for non-SCT patients were 34.5% higher than for SCT.

The HCRU and cost data shown are all-cause. LBCL-related utilization and costs were also calculated, defined as an LBCL diagnosis in the primary position of the claim, or LBCL chemotherapy treatment, or treatment for an LBCL-related adverse event (defined below). Disease-specific HCRU and costs showed similar patterns to all-cause and are available in Supplementary Tables 3 & 4.

Adverse events recorded were thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, anemia, febrile neutropenia, infection, pneumonia, acute respiratory failure, acute renal failure, acute heart failure and nausea or vomiting. See Supplementary Table 5 for codes used to identify adverse events. Of these, the most common event in both groups was infection; the costliest in terms of mean cost per patient who experienced the event were febrile neutropenia (non-SCT $24,423 and SCT $19,218) and infection (non-SCT $12,723 and SCT $15,959). The incidence of all events was higher in the SCT group, except for leukopenia, renal failure, heart failure and nausea or vomiting, the rates of which did not significantly differ. Conversely, however, the mean adverse event cost per patient was significantly higher in the non-SCT group than in the SCT group for all but anemia, infection and pneumonia, which did not significantly differ.

Discussion

The goal in relapsed or refractory LBCL following first LOT is chemotherapy in preparation for a SCT, but in this study of older Medicare patients, only 22.0% of patients ever received an ASCT-intended second LOT. The low rate of aggressive second LOTs in these patients may indicate that their providers did not feel they could tolerate salvage chemotherapy and therefore employed less cytotoxic treatments such as bendamustine-based regimens, which are considered more tolerable in elderly patients [Citation12].

It is worthwhile to note that 13% of the ASCT-intended cohort were recoded from the ASCT-not-intended group because they received an ASCT after a second LOT despite not receiving a SCT preparative regimen. This may be an indication that treating physicians maintain the possibility of a SCT in elderly patients who are able to tolerate a less toxic regimen and/or have a positive response to chemotherapy.

Only 23.3% of ASCT-intended patients in this study ultimately received SCT; the remaining 76.7% were SCT-intended but never received a transplant. This means that, for the entire study sample, only 5.1% of the 4758 elderly LBCL patients who failed first LOT ever received a SCT, which is considerably less than the approximately 25% previously reported in the literature [Citation4–6]. Compared with the SCT patients, the non-SCT patients were 5 years older on average and had more comorbidities. Only 10.7% of patients who received an SCT were 75 years of age or older, while the ASCT-intended cohort overall included 38.4% of patients in this age group. This difference may be due to a reluctance by providers to recommend a SCT to older patients even after an ASCT-intended regimen, or to a lower response rate among patients older than 75 years.

The impact of age can be seen even earlier in the treatment process, in that the ASCT-intended cohort was significantly younger than the ASCT-not-intended group, reflecting a difference in the choice of second LOT regimen associated with age. In fact, age was the only factor, other than gender, on which the ASCT-intended and not-intended groups differed; they did not differ significantly on race, dual status or CCI. While claims data cannot provide insight into the reasons why providers chose one treatment regimen over another, age is a consideration in making the treatment decisions and may lead to a low rate of elderly patients receiving the standard second-line SCT following failure of the first LOT.

This study also observed a potential disparity in access to SCT among low-income Medicare beneficiaries for similarly eligible patients. Dual-eligible Medicare patients represented 11.1% of the ASCT-intended population but only 4.5% of the patients who ultimately received a transplant. At least part of this disparity may be due to the patient co-pays. Many Medicare beneficiaries may have supplemental insurance that covers their portion of the SCT allowed amount. For Medicaid, although all states provide coverage for SCT, there is considerable state-to-state variation in the amount and type of Medicaid coverage, and frequently the coverage may be inadequate for successful transplantation, including restrictions on the indication, limitations on the number of inpatient days allowed per year, differences in allowed reimbursement amount and absence of coverage for searching for a donor [Citation15]. By federal law, any disparities in paid amounts between Medicare and Medicaid cannot be passed on to the patient.

Furthermore, there may be additional social risk factors (e.g., education level, race/ethnicity, language barriers, access to specialists and treatment centers) that may be contributing to this gap in treatment. The extent to which Medicaid coverage or other social determinants of health may account for the apparent disparity in SCT was not included in this study but could be included in future research.

Despite the overall clinical picture, nearly 40% of non-SCT patients in this study received a regimen with therapeutic intent as third LOT or higher, which may suggest that their clinicians felt there was potential benefit to further treatment. The literature has shown, however, that continued lines of chemotherapy after the second line tend to introduce additional costs and risks of adverse events to patients, with decreasing likelihood of survival benefit [Citation8,Citation9,Citation13].

Non-SCT patients had higher rates of HCRU and treatment costs in all utilization categories except for hospitalizations, including twice as many ED visits on a PPPM basis. Non-SCT patients were also higher consumers of post-acute care (skilled nursing facility and home health), and nearly half (48.1%) went into hospice post-second LOT, versus 18.9% of SCT patients. This latter finding suggests that, while SCT is often curative, for nearly 20% of these patients, SCT was ultimately unsuccessful during the study period.

The higher hospital utilization for the SCT group likely reflects the SCT procedure itself (94% of SCTs were performed in the inpatient setting). While SCT patients had higher overall costs compared with non-SCT patients, this is not surprising as other published data have shown that the hospitalization for the SCT procedure itself makes up a significant part of the costs for these patients [Citation8,Citation14]. In addition, the non-SCT cohort showed higher costs in every other utilization category and also experienced adverse events that were generally more costly than those in the SCT group.

One limitation of this study was that the comparison groups were not matched and patients needed to survive at least until initiation of a second LOT; therefore selection and immortal time biases may exist. Additionally, as with other retrospective database studies, the results were based on claims, which lack clinical detail and are subject to potential unobservable factors that may influence the outcomes. It is also difficult to assess any causal inference from observational, claims-based data. For example, we have shown that a certain proportion of ASCT-intended patients never received a transplant, but we can not directly infer whether that was due to toxicities of second-line treatment, failure to achieve an adequate response to that treatment, or some other reason.

Despite these limitations, these data suggest a large unmet need for elderly patients with relapsed/refractory LBCL. Many relapsed/refractory LBCL patients never receive a second LOT regimen that qualifies them for a SCT, and of those who do qualify, many do not ultimately receive a transplant. Nearly 40% of those who do not receive a potentially curative SCT continue to receive chemotherapy, incurring additional direct treatment costs and secondary costs for the treatment of side effects as well as increasing the risk for a decline in their quality of life, all of which are associated with increasingly negative long-term survival outcomes. Recent advances in cell and gene therapy, such as chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy, may be changing the landscape for treatment of patients with relapsed/refractory LBCL. The development of newer, effective therapies may fill the gap in available treatments for these patients, and further research into the potential of these treatments is ongoing.

Conclusion

The standard of care in relapsed or refractory LBCL following first LOT is salvage chemotherapy followed by SCT. In this study of older Medicare patients, only 5.1% of relapsed/refractory patients ever received a transplant. Even among patients who were intended for a transplant, based on their second LOT regimen, only 23.3% received one. The remainder had higher healthcare utilization and costs associated with emergency department, outpatient and post-acute care, and over one-third received additional curative therapies for the LBCL, which is known to have diminishing returns. The development of newer therapies such as chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy may provide an additional effective treatment option for these patients.

The current goal in relapsed or refractory large B cell lymphoma (LBCL) is autologous stem cell transplant (SCT), but in our study we found that only 22.0% of elderly relapsed/refractory LBCL patients ever received an SCT-intended second-line regimen.

Furthermore, only 23.3% of these SCT-intended patients ultimately received a transplant.

In total, only 5.1% of elderly second-line LBCL patients ultimately received SCT.

Compared with the SCT patients, the non-SCT patients were older, had more comorbidities and had higher rates of healthcare utilization and costs post-second-line therapy in all categories (except acute inpatient care).

38.7% of non-SCT patients proceeded to additional lines of lymphoma-directed therapies beyond the second line, which may suggest that their clinicians felt there was potential benefit to further treatment.

These data suggest there may be unmet need for elderly patients with LBCL.

Author contributions

K Kilgore, I Mohammadi, A Wong and J Snider contributed to the conception and design of the research; I Mohammadi, K Kilgore and A Wong contributed to the acquisition and analysis of the data; all authors contributed to the interpretation of the data; K Kilgore drafted the manuscript; all authors critically revised the manuscript, agree to be fully accountable for ensuring the integrity and accuracy of the work, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical conduct of research

This retrospective study involved only secondary analysis of existing, de-identified datasets, and therefore does not constitute human subjects research as defined at 45 CRF 46.102.

Figure 1. Overall Survival, Relative to Start of 2nd LOT, ASCT-Intended, Stratified by Time-to-Relapse

Download MS Word (50.1 KB)Table 1. Standard First and Second LOT Regimens1

Download MS Word (169.6 KB)suppl_file

Download Zip (163.6 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank S Yande for research support and Bridget Flavin (Connected Content, Ltd) for providing medical writing assistance as an independent contractor to Avalere Health.

Supplementary data

To view the supplementary data that accompany this paper please visit the journal website at: www.tandfonline.com/doi/suppl/10.2217/fon-2021-0607

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This study was funded by Kite, a Gilead Company. J Snider, A Patel and P Cheng are full-time employees of Kite, a Gilead Company, and hold stock in the company. K Kilgore, A Wong, A Schroeder and I Mohammadi are full-time employees of Avalere Health, who were paid consultants to Kite for the conduct of this study. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Bridget Flavin, Connected Content, Ltd, provided medical writing assistance as an independent contractor to Avalere Health.

Additional information

Funding

References

- National Cancer Institute . Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program. Cancer stat facts: non-Hodgkin lymphoma (2021). https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/nhl.html

- National Cancer Institute . Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program. Cancer Stat Facts: NHL – diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) (2021). https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/dlbcl.html

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network . B-Cell Lymphomas (version 4.2020) (2020). www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/b-cell.pdf

- Crump M , NeelapuSS, FarooqUet al. Outcomes in refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: results from the international SCHOLAR-1 study. Blood130(16), 1800–1808 (2017).

- Van Den Neste E , SchmitzN, MounierNet al. Outcome of patients with relapsed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma who fail second-line salvage regimens in the International CORAL study. Bone Marrow Transplant.51(1), 51–57 (2016).

- Galaznik A , HuelinR, StokesMet al. Systematic review of therapy used in relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and follicular lymphoma. Future Sci. OA4(7), FSO322 (2018).

- Snider JT , ChengP, SongX, McMorrowD, DiakunD. Lines of therapy in patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma and stem cell transplant-intended treatment. Blood136(Suppl. 1), 45–46 (2020).

- Purdum A , TieuR, ReddySR, BroderMS. Direct costs associated with relapsed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma therapies. Oncologist24(9), 1229–1236 (2019).

- Tkacz J , GarciaJ, GitlinMet al. The economic burden to payers of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma during the treatment period by line of therapy. Leuk. Lymphoma61(7), 1601–1609 (2020).

- Deyo RA , CherkinDC, CiolMA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J. Clin. Epidemiol.45(6), 613–619 (1992).

- Quan H , SundararajanV, HalfonPet al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med. Care43(11), 1130–1139 (2005).

- Storti S , SpinaM, PesceEAet al. Rituximab plus bendamustine as front-line treatment in frail elderly (>70 years) patients with diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a Phase II multicenter study of the Fondazione Italiana Linfomi. Haematologica103(8), 1345–1350 (2018).

- Danese MD , GriffithsRI, GleesonMLet al. Second-line therapy in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL): treatment patterns and outcomes in older patients receiving outpatient chemotherapy. Leuk. Lymphoma58(5), 1094–1104 (2017).

- Cho SK , McCombsJ, PunwaniN, LamJ. Complications and hospital costs during hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for non-Hodgkin lymphoma in the United States. Leuk. Lymphoma60(10), 2464–2470 (2019).

- Preussler JM , FarniaSH, DenzenEM, MajhailNS. Variation in Medicaid coverage for hematopoietic cell transplantation. J. Oncol. Pract.10(4), e196–200 (2014).