Abstract

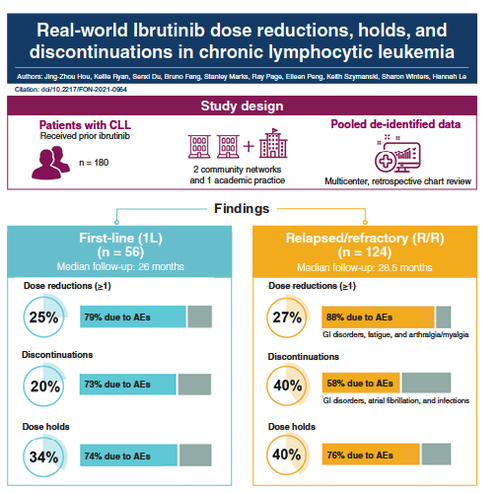

Aim: A retrospective chart review of ibrutinib-treated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) was conducted. Patients & methods: Adults with CLL who initiated ibrutinib were followed for ≥6 months (n = 180). Results: Twenty-five percent of first-line ibrutinib patients experienced ≥1 dose reduction, mainly due to adverse events (AEs; 79%). Treatment discontinuations and dose holds occurred in 20 and 34% of patients, respectively, most commonly due to AEs (73 and 74%). Approximately one-quarter of relapsed/refractory ibrutinib patients experienced ≥1 dose reduction, mainly due to AEs (88%). Treatment discontinuation and dose holds occurred in 40% of patients (58 and 76% due to AEs, respectively). Conclusion: Dose reductions, holds and discontinuations were frequent in patients with CLL receiving ibrutinib in routine clinical practice.

Lay abstract

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is a cancer that develops from a type of white blood cells called ‘B cells.’ Ibrutinib is a targeted therapy that inhibits the activity of a protein called Bruton’s tyrosine kinase, which plays a key role in CLL. Patients receiving ibrutinib treatment can experience side effects (‘adverse events’). In addition, patients may need to reduce their drug dose (‘dose reductions’) or stop treatment (‘discontinuations’) for a variety of reasons. We reviewed patients’ charts to describe dose reductions and discontinuations in ibrutinib-treated patients with CLL. Our results indicate that dose reductions and discontinuations were frequent in patients with CLL receiving ibrutinib in routine clinical practice, and that the most common reason was adverse events.

Tweetable abstract

Real-world data from a retrospective chart review of ibrutinib-treated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia show that dose reductions and discontinuations are frequent in routine clinical practice, and the most common reason for both was adverse events. #CLL #chroniclymphocyticleukemia.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most common chronic leukemia in the United States, with over 20,000 new cases expected each year [Citation1]. CLL is characterized by accumulation of clonal B lymphocytes, the typical phenotype including CD5+, CD19+ and CD23+ B cells [Citation2–4]. Older white males have the greatest incidence of CLL [Citation5]. The majority (88–96%) of patients with CLL in the USA are treated in community practice settings [Citation6,Citation7]; however, real-world studies of patients with CLL have previously focused on the academic setting or registry data.

Historically, chemo-immunotherapy regimens (e.g., chlorambucil in combination with an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody) had been the standard of care in CLL, particularly in the first-line (1L) setting [Citation8,Citation9]. With the initial approval of ibrutinib to treat previously treated CLL in 2014 and expansion of the indication to treatment of 1L CLL in 2016, this Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor (BTKi) quickly became standard of care for the treatment of CLL [Citation10]. The recent advent of novel targeted agents with high efficacy and better safety profiles has led to changes in the standard of care across all lines of therapy. Current guidelines recommend ibrutinib and acalabrutinib, a second-generation BTKi, as monotherapy, or acalabrutinib in combination with the anti-CD20 antibody obinutuzumab, and the combination of the BCL-2 inhibitor venetoclax and obinutuzumab as the preferred regimens for 1L CLL regardless of age, comorbidities or del(17p)/TP53 status under National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, and for unfit patients without TP53 mutation under the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines [Citation3,Citation4]. Like the 1L setting, novel targeted agents have become standard of care in the relapsed/refractory (R/R) setting of CLL. Current NCCN guidelines recommend ibrutinib, acalabrutinib and venetoclax combination therapy with either obinutuzumab or rituximab as preferred regimens for all patient types in both 1L and R/R CLL [Citation3]. The ESMO guidelines recommend ibrutinib or acalabrutinib monotherapy, and either venetoclax or idelalisib in combination with rituximab [Citation4].

Clinical trials evaluate novel agents in a closely controlled setting and have demonstrated the safety and efficacy of these agents among select groups of participants; however, it is important to assess health outcomes in real-world populations, as clinical trials are not typically representative of real-world practice. Real-world studies of ibrutinib in CLL have shown higher rates of discontinuations due to adverse events (AEs; 14–29%) [Citation11–13], compared with data reported in the initial results from Phase III clinical trials of ibrutinib (4–9%) [Citation14,Citation15]. Similarly, dose reduction rates due to AEs in real-world studies were 10–31% [Citation16–18] versus 9% listed on the ibrutinib prescribing information [Citation10].

This study aimed to further expand the published literature on the real-world use of ibrutinib among patients with CLL by examining the treatment patterns of ibrutinib in broader community networks and one academic practice. The primary objective of this study was to describe ibrutinib dose reductions, discontinuations and holds among patients with CLL and to assess the reasons for these decisions in the context of routine clinical practice.

Methods

Study design

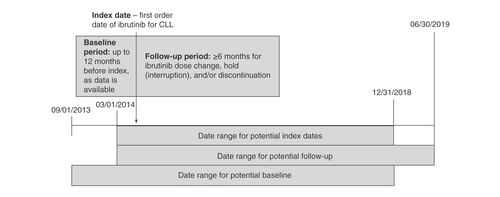

This was a multicenter, retrospective chart review study of patients with CLL treated with ibrutinib between March 2014 and June 2019. Index date was defined as the date of ibrutinib initiation. Patients were followed a minimum of 6 months after index date through the date of the last patient encounter ().

Data source

Deidentified data were abstracted from electronic medical records from two community networks and one academic practice and pooled together. To minimize the burden on community practices, each community network contributed 50 patients to the pooled data. To minimize potential bias, the patients were randomly selected from all eligible ibrutinib-treated patients in each network. All patients meeting inclusion criteria from the academic site were included in the pooled data. The study protocol was determined to be exempt from expedited or full ethical review by the Western Institutional Review Board (WA, USA) prior to starting data collection. This observational study was performed in accordance with ethical principles that are consistent with the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Conference on Harmonisation’s Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice, the Guidelines for Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices and applicable legislation on noninterventional studies and/or observational studies. This research utilized retrospective data only.

Study population

Patients were eligible for inclusion in the study if they had a confirmed diagnosis of CLL, initiated ibrutinib between March 2014 and June 2019 and were ≥18 years of age at index date. Patients were excluded if they had less than 1 month of baseline data prior to index date, initiated ibrutinib less than 6 months before the index date, were part of an interventional clinical trial during the baseline or follow-up period, or initiated ibrutinib prior to 1 March 2014. Patients who were receiving treatments for another primary cancer besides CLL during the follow-up period or who were pregnant at any point during the baseline and follow-up period were also excluded. Because the aim of this study was to assess the ibrutinib use in the real-world context, patients were not excluded based on any pre-existing comorbidities.

Measures

Key baseline variables abstracted from the medical charts included demographics, CLL characteristics, baseline comorbidities and concomitant medications. Baseline characteristics were collected at index date and up to 12 months prior to index date (pre-index period) with the exception of some clinical characteristics. The following CLL diagnosis characteristics were also abstracted if available: initial CLL diagnosis date, bulky lymph nodes, number of treatments for CLL prior to ibrutinib and regimens for CLL prior to ibrutinib. The primary outcomes assessed were ibrutinib dose reductions, dose holds and discontinuations, as well as reasons for these outcomes. Additional outcomes measured included time-to-next treatment and the duration of therapy.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the results. Categorical variables were reported as counts and percentages, and continuous variables were reported as means with standard deviations or medians with ranges where appropriate. Counts and percentages of missing data for all variables were reported. In this study, ‘not documented’ indicates that the investigator sought the data point, but it was confirmed by abstractor as not available in the patient chart. Statistical analyses were completed using Statistical Analysis Software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, NC, USA).

Results

Overall patient population

A total of 180 patients with CLL were included in this study. Of these, 56 (31%) patients received ibrutinib as 1L therapy and 124 (69%) patients received ibrutinib in a R/R setting. Over half (n = 100; 56%) of a total of 180 patients in this study were treated in a community setting. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in .

Table 1. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia receiving ibrutinib.

A total of 41 patients experienced a dose reduction and 37 patients discontinued ibrutinib due to an AE (). Among first dose reductions, 33 patients had a dose reduction to 280 mg, and nine patients had a dose reduction to 140 mg. Most common AEs (>20%) leading to dose reduction in the overall population were gastrointestinal (GI) disorders, fatigue and hematologic abnormalities. Most common AEs (>20%) leading to discontinuation were GI disorders and atrial fibrillation. Overall, there were 11 (6%) patients who did not have atrial fibrillation at baseline and went on to experience atrial fibrillation during the treatment with ibrutinib. Among the 26 patients with atrial fibrillation at baseline, seven patients had a dose reduction (one patient had two dose reductions; three patients eventually discontinued treatment) and 12 patients discontinued ibrutinib (four of these discontinuations were due to atrial fibrillation).

Table 2. Adverse events responsible for dose reductions/discontinuationsTable Footnote†.

First-line ibrutinib patients

For 1L ibrutinib patients, the median age was 70.5 years and 62.5% of patients were male. Fourteen percent of patients had atrial fibrillation and 7% had congestive heart failure as a baseline comorbidity. Twenty-seven percent of patients had del(17p) (41% negative and 32% with test not documented), 14% had del(11q) (45% negative and 41% with test not documented) and 45% had del(13q) (27% negative and 29% with test not documented).

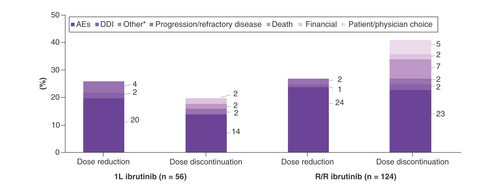

For the 56 patients receiving 1L ibrutinib, the majority (89%) received ibrutinib as monotherapy, initiated at full dose (420 mg daily). Median follow-up was 26 months in patients receiving 1L ibrutinib. Twenty-five percent of patients experienced at least one dose reduction, mainly due to AEs (79%; ). The second most common reason for dose reduction was drug–drug interactions (7%). There was no single AE primarily responsible for dose reduction (). Median time to first dose reduction for 1L patients was 9.9 months.

*Abstractors were instructed to categorize reasons for dose reductions as AE, DDI or other. Reasons for dose reductions in the ‘Other’ category included prior history of atrial fibrillation, patient or physician choice, and patient compliance. For discontinuations, the categories available to abstractors were AE, DDI, progression/refractory disease, death, financial, patient/physician choice and other. Reasons for discontinuations in the ‘Other’ category included remission and cerebrovascular accident.

1L: First-line; AE: Adverse event; CLL: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia; DDI: Drug–drug interaction; R/R: Relapsed/refractory.

Among the 34% of patients in whom dose holds were reported, all patients had only a single dose hold; these were most commonly due to AEs (74%). The most common AEs that led to dose holds included infection, GI disorders and neutropenia (14% each). The median duration of a dose hold was 19 days.

Treatment discontinuations were reported in 20% of 1L patients; they were more commonly due to AEs (73%) than disease progression (9%). One discontinuation was due to patient death (9%). A variety of AEs led to discontinuations, the most common being atrial fibrillation (). The median duration of treatment (DOT) of 1L ibrutinib patients was 25 months (range: 0.9–62 months). Among patients who discontinued ibrutinib, overall median DOT was 15 months; median DOT was 6 months for those who discontinued due to AEs (n = 8) and 29 months for the single patient who discontinued due to disease progression ().

Table 3. Time to discontinuation/first dose reduction.

Results were generally similar between academic- and community-treated patients ().

Relapsed/refractory ibrutinib patients

For R/R patients, the median age was 68.0 years and 66.9% of patients were male. Two percent of patients had prior bleeding, 14% had atrial fibrillation and 10% had congestive heart failure as a baseline comorbidity. Fourteen percent of patients had del(17p) (33% negative and 52% with test not documented), 19% had del(11q) (25% negative and 57% with test not documented) and 32% had del(13q) (27% negative and 40% with test not documented).

For R/R ibrutinib patients, the majority received ibrutinib as monotherapy (93%), initiated at full dose (89%; 420 mg daily). Median follow-up was 28.5 months in R/R ibrutinib patients. About a quarter (27.4%) of patients experienced at least one dose reduction, mainly due to AEs (88%; ). The most common AEs leading to the first dose reductions were GI disorders (43%) such as diarrhea and stomatitis, fatigue (23%) and arthralgia/myalgia (17%; ). Median time to the first dose reduction in R/R patients was 3.1 months.

Dose holds were reported in 40% of patients, with the majority (92%) experiencing a single dose hold. Most dose holds were due to AEs (76%). The most common AEs that led to dose holds were infections (24%) and GI disorders (21%). Median time to first dose hold was 27 months, and the median duration of a dose hold was 25 days.

Treatment discontinuation was reported in 40% of patients, again mostly due to AEs (58%) rather than disease progression (18%). The most common AEs leading to discontinuation were GI disorders (31%), atrial fibrillation (24%) and infections (21%; ). One bleeding event (GI hemorrhage) was the reason for discontinuation in a patient who had received anticoagulants. For two (4%) patients with R/R CLL, the reason for discontinuation was death.

The median DOT of R/R ibrutinib patients was 14.9 months (range: 0.3–61.4 months). For patients who discontinued ibrutinib, the median DOT was 9 months (). Patients who discontinued due to an AE (n = 29) had a median DOT of 6.2 months and patients who discontinued due to disease progression (n = 9) had a median DOT of 30.2 months.

Results were generally similar between academic- and community-treated patients ().

Discussion

Our study identified that dose reductions, dose holds and treatment discontinuations were frequent in patients with 1L and R/R CLL who received ibrutinib in routine clinical practice. AEs were the primary cause for all three treatment modifications assessed in this study. Interestingly, most AE-related treatment modifications occurred in the first 9 months of treatment as opposed to progression-related treatment changes, which occurred later in the treatment. Whereas most of the literature on this topic focuses on academic settings, our study contributes information about ibrutinib patterns in both the community and academic settings.

Our study demonstrated higher rates of dose reductions due to AEs in patients receiving ibrutinib compared with clinical trials. These findings are consistent with other recent studies on the real-world use of ibrutinib. In their retrospective analysis of 616 patients treated with ibrutinib, Mato et al. documented that 15% of front-line and 20% of R/R ibrutinib-treated patients required a dose reduction [Citation19]. In another retrospective analysis conducted at a tertiary care academic cancer center, among 70 patients with CLL receiving ibrutinib (90% of whom had received prior therapy), a total of 23 (31%) patients required dose reductions due to AEs or other causes [Citation20]. The 25% of 1L and 27% of R/R ibrutinib patients who had a dose reduction in our study are in line with those findings but substantially higher than the 4% of patients requiring dose reduction due to AEs in the RESONATE trial (R/R CLL) and no patients requiring dose reduction in the RESONATE-2 trial (1L CLL) [Citation14,Citation15]. The 5-year RESONATE-2 results showed dose reduction due to AEs of any grade occurring in 20% of patients, with yearly rates of 5–9% [Citation21], highlighting the longer-term issues associated with AEs in ibrutinib patients even in the clinical trial setting.

Treatment discontinuations were more common in R/R patients than 1L patients despite similar median length of follow-up. However, the majority of discontinuations in both groups were due to AEs. Overall, 21% of the ibrutinib patients in this study discontinued treatment due to an AE. This is substantially higher than the initial clinical trial results from RESONATE and RESONATE-2 but similar to the 5-year follow-up report of RESONATE-2 in treatment-naive CLL, where 41% of patients reported discontinuations, with 21% of patients discontinuing due to AEs [Citation21]. Previous real-world studies of ibrutinib in both the academic and community settings have found discontinuation rates ranging from 16 to 50%, with rates of discontinuation due to AEs of 14–29% (). These reports of discontinuations with longer-term follow-up demonstrate the value of real-world research to validate clinical trial findings and also highlight a potential unmet need for patients with CLL.

Table 4. Summary of the literature on ibrutinib discontinuations and dose reductions in real-world treatment settings.

Patients who discontinued due to AEs had a substantially shorter median duration of therapy compared with patients who discontinued due to disease progression. Both 1L and R/R patients who discontinued due to AEs had a median duration of therapy of 6 months compared with over 2 years for patients discontinuing due to progression. Again, this is consistent with the findings of Mato et al., who documented duration of therapy ranging from 3.5 to 8 months for those discontinuing due to an AE. Increased focus on the first 6 months of therapy by healthcare professionals may identify opportunities for early identification or avoidance of AEs, ultimately leading to discontinuation [Citation19].

The median age and percentage of male patients are similar between our study population and the ibrutinib clinical trials (1L CLL: 70 years; 63% compared with RESONATE-2: 73 years; 65%; R/R CLL: 69 years, 67% compared with RESONATE: 67 years, 66%). However, our study includes patients with comorbidities such as atrial fibrillation and congestive heart failure, who would have been excluded from participating in clinical trials. In addition, several of the patients in our study receiving ibrutinib for 1L or R/R CLL were on concomitant therapies such as anticoagulants (∼9–11%), antiplatelets (∼20–25%) and antiarrhythmics (∼7–11%). Patients with such comorbidities and concomitant therapies are more prevalent in the real-world setting, and these factors may contribute to the increased rate of dose reductions and discontinuations seen in our study population. For example, some patients who eventually had a dose reduction or discontinued ibrutinib due to atrial fibrillation also had atrial fibrillation at baseline, and the only patient who discontinued due to a bleeding event had received anticoagulants.

This study offers valuable data from both academic- and community-based networks on real-world ibrutinib treatment patterns. Other kinase inhibitors, such as acalabrutinib and venetoclax, were not approved during the study period and were not included in this analysis. However, there are several other limitations for consideration. Our study utilized medical records that are created for the purpose of patient care, not for research, and may contain errors or missing information. Moreover, there may be variation in the extent of provider reporting of patient characteristics and reasons for reductions and discontinuation of ibrutinib regimens. Patients initiating therapy more recently in the study had limited follow-up; therefore, true duration of therapy, rates of dose reduction and discontinuations may be underestimated for those patients. Finally, while we included both academic and community networks from diverse geographic locations, these results may not be generalizable to all patients with CLL. In order to avoid placing undue burden on community practices, which may lack resources to abstract data from patients’ medical records, we included a random sampling of 50 eligible patients treated within each of the community networks during the defined study period. Future research should sample larger patient populations with appropriate statistical power to investigate the similarities between the study population and broader CLL population and whether certain comorbidities, concomitant medications or other disease characteristics are statistically associated with increased risk for dose reduction or discontinuation.

The rates of ibrutinib dose reductions and discontinuations due to AEs in our study were higher than in clinical trials and were consistent with other real-world studies. Patients with CLL that have favorable responses and are able to remain on treatment may experience well-controlled disease as well as other survival benefits. Future research should focus on understanding the factors associated with developing AEs and on strategies and interventions to mitigate or avoid AEs that result in treatment discontinuation.

Conclusion

Real-world evidence on ibrutinib treatment in patients with CLL is important because while clinical trials traditionally take place in an academic setting, most patients with CLL are treated in community settings and have higher rates of comorbidities than clinical trial participants. Here, we demonstrate AEs are the main cause of ibrutinib dose reductions and discontinuations in real-world settings. These results highlight the need for continued focus on optimizing AE management for patients on long-term therapy, as well as developing newer therapies with improved tolerability.

The primary objective of this retrospective study was to describe ibrutinib treatment patterns, including dose reductions and discontinuations, and to assess reasons for such in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) in real-world practice.

Deidentified data were pooled from two community networks and one academic practice, with each community network contributing 50 patients and an academic practice contributing 80 patients.

A total of 180 patients with CLL were included in this analysis (31% first-line, 69% relapsed/refractory) with more than half (56%) being treated in a community setting.

Dose discontinuations and reductions were frequent in patients with CLL, who were treated with ibrutinib in routine clinical practice.

The most common reasons leading to discontinuation of ibrutinib were adverse events (AEs).

Patients who discontinued ibrutinib due to AEs had a substantially shorter duration of therapy than patients discontinuing for other reasons.

The rates of dose discontinuations or reductions due to AEs in our study were higher than in ibrutinib clinical trials and were consistent with other real-world studies in CLL.

Future research should sample larger patient populations to investigate whether certain comorbidities, concomitant medications or other disease characteristics are statistically associated with dose reduction or discontinuation.

Author contributions

J-Z Hou, S Winters, K Ryan, K Szymanski and H Le contributed to the study design. J-Z Hou, K Ryan, K Szymanski, B Fang, H Le, S Marks, R Page and E Peng completed the data analysis/interpretation. Data collection was done by S Du. All the authors contributed to the critical revision and review of the manuscript. Project/data management was done by J-Z Hou, S Winters, K Ryan and H Le. All the authors were responsible for the approval of final draft for submission.

Ethical conduct of research

The study protocol was determined to be exempt from expedited or full ethical review by the Western Institutional Review Board (WA, USA) prior to starting data collection. This observational study was performed in accordance with ethical principles that are consistent with the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Conference on Harmonisation’s Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice, the Guidelines for Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices and applicable legislation on noninterventional studies and/or observational studies.

Data-sharing statement

Data underlying the findings described in this manuscript may be obtained in accordance with AstraZeneca’s data sharing policy described at https://astrazenecagrouptrials.pharmacm.com/ST/Submission/Disclosure.

Infographic

Download PDF (1.6 MB)Supplementary data

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This study was funded by AstraZeneca. AstraZeneca provided funding for Covance to conduct the data analysis. J-Z Hou has received a research grant (paid to institution) from AstraZeneca. K Ryan, K Szymanski and H Le are employees and equity holders of AstraZeneca. S Du, B Fang and S Marks have nothing to disclose. R Page has served in a consulting/advisory role for AstraZeneca, Tesaro, Amgen, Hoffmann LaRoche and Quality Care Cancer Alliance; has received research funding from ER Squibb Sons, LLC, Gilead Sciences, Takeda, AstraZeneca, Genentech, F. Hoffmann LaRoche AG, Janssen, Celgene and Lilly; and has had travel, accommodations and expenses paid by Amgen, Taiho Pharmaceutical, and Takeda. E Peng has received a research grant from AstraZeneca. S Winters has received fees for data collection, preparation of electronic data collection tool, report preparation and oversight from AstraZeneca. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Medical writing assistance, funded by AstraZeneca, was provided by Tracy Diaz, Jennifer Darby and Claire L Jarvis of Peloton Advantage, LLC, an OPEN Health company, under the direction of the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Siegel RL , MillerKD, JemalA. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J. Clin.70(1), 7–30 (2020).

- Hallek M . Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: 2015 Update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and treatment. Am. J. Hematol.90(5), 446–460 (2015).

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network . NCCN Clinical Practice guidelines in oncology: chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma version 1.2022. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2021). www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cll.pdf

- Eichhorst B , RobakT, MontserratEet al. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: ESMO Clinical Practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol.32(1), 23–33 (2021).

- Introduction. In: SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2017.HowladerN, NooneAM, KrapchoMet al. ( et al. Eds). National Cancer Institute, MD, USA, 1–7 (2020).

- Mato AR , BarrientosJC, GhoshNet al. Prognostic testing and treatment patterns in chronic lymphocytic leukemia in the era of novel targeted therapies: results from the informCLL Registry. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk.20(3), 174–183.e173 (2020).

- Mato A , NabhanC, LamannaNet al. The Connect CLL Registry: final analysis of 1494 patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia across 199 US sites. Blood Adv.4(7), 1407–1418 (2020).

- Hallek M , FischerK, Fingerle-RowsonGet al. Addition of rituximab to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet376(9747), 1164–1174 (2010).

- Goede V , FischerK, BuschRet al. Obinutuzumab plus chlorambucil in patients with CLL and coexisting conditions. N. Engl. J. Med.370(12), 1101–1110 (2014).

- Imbruvica [package insert]. Pharmacyclics, Janssen Biotech, Inc, PA, USA (2020). www.imbruvica.com/files/prescribing-information.pdf

- Sharman JP , Black-ShinnJL, ClarkJ, BitmanB. Understanding ibrutinib treatment discontinuation patterns for chronic lymphocytic leukemia [abstract]. Blood130(Suppl. 1), 4060 (2017).

- Hampel PJ , DingW, CallTGet al. Rapid disease progression following discontinuation of ibrutinib in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated in routine clinical practice. Leuk. Lymphoma60(11), 2712–2719 (2019).

- Parikh SA , AchenbachSJ, CallTGet al. The impact of dose modification and temporary interruption of ibrutinib on outcomes of chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients in routine clinical practice. Cancer Med.9(10), 3390–3399 (2020).

- Burger JA , TedeschiA, BarrPMet al. Ibrutinib as initial therapy for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med.373(25), 2425–2437 (2015).

- Byrd JC , BrownJR, O’BrienSet al. Ibrutinib versus ofatumumab in previously treated chronic lymphoid leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med.371(3), 213–223 (2014).

- Frei CR , LeH, McHughDet al. Treatment patterns and outcomes of 1205 patients on novel agents in the US Veterans Health Administration (VHA) System: results from the largest retrospective EMR and chart review study in the real-world setting [abstract]. Blood134(Suppl. 1), 795 (2019).

- Hardy-Abeloos C , PinottiR, GabriloveJ. Ibrutinib dose modifications in the management of CLL. J. Hematol. Oncol.13(1), 66 (2020).

- Dimou M , IliakisT, PardalisVet al. Safety and efficacy analysis of long-term follow up real-world data with ibrutinib monotherapy in 58 patients with CLL treated in a single-center in Greece. Leuk. Lymphoma60(12), 2939–2945 (2019).

- Mato AR , NabhanC, ThompsonMCet al. Toxicities and outcomes of 616 ibrutinib-treated patients in the United States: a real-world analysis. Haematologica103(5), 874–879 (2018).

- Akhtar OS , AttwoodK, LundI, HareR, Hernandez-IlizaliturriFJ, TorkaP. Dose reductions in ibrutinib therapy are not associated with inferior outcomes in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Leuk. Lymphoma60(7), 1650–1655 (2019).

- Burger JA , BarrPM, RobakTet al. Long-term efficacy and safety of first-line ibrutinib treatment for patients with CLL/SLL: 5 years of follow-up from the phase 3 RESONATE-2 study. Leukemia34(3), 787–798 (2020).

- Huntington SF , SoulosPR, BarrPMet al. Utilization and early discontinuation of first-line ibrutinib for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated in the community oncology setting in the United States [abstract]. Blood134(Suppl. 1), 797 (2019).

- Iskierka-Jażdżewska E , HusM, GiannopoulosKet al. Efficacy and toxicity of compassionate ibrutinib use in relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia in Poland: analysis of the Polish Adult Leukemia Group (PALG). Leuk. Lymphoma58(10), 2485–2488 (2017).