Abstract

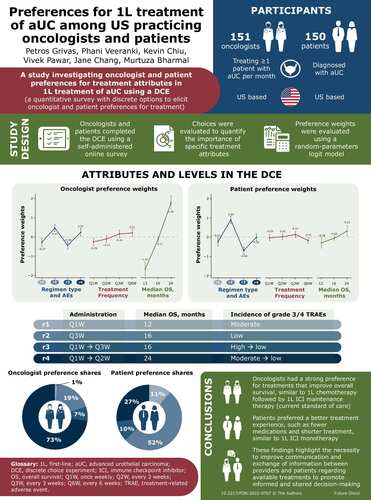

Aim: Investigate oncologist and patient preferences for the first-line treatment of advanced urothelial carcinoma. Materials & methods: A discrete-choice experiment was used to elicit treatment attribute preferences, including patient treatment experience (number and duration of treatments and grade 3/4 treatment-related adverse events), overall survival and treatment administration frequency. Results: The study included 151 eligible medical oncologists and 150 patients with urothelial carcinoma. Both physicians and patients appeared to prefer treatment attributes related to overall survival, treatment-related adverse events and the number and duration of the medications in a regimen over frequency of administration. Overall survival had the most influence in driving oncologists' treatment preferences, followed by the patient’s treatment experience. Patients found the treatment experience the most important attribute when considering options, followed by overall survival. Conclusion: Patient preferences were based on treatment experience, while oncologists preferred treatments that prolong overall survival. These results help to direct clinical conversations, treatment recommendations and clinical guideline development.

Plain language summary

Different treatments are available for people with urothelial cancer that has spread to other parts of the body. Researchers wanted to find out what specialist cancer doctors and people with urothelial cancer think is important when choosing the first treatment. To do this, researchers asked 150 cancer specialists and 150 people with urothelial cancer to complete an internet questionnaire. It included questions about side effects, if treatment could help people live longer, and how often people would need to be treated. Researchers found that cancer specialists think that helping people live longer is the most important. However, people with advanced urothelial cancer think that having fewer severe side effects is the most important.

Bladder cancer is the fourth most common cancer in men and predominately affects individuals over 55 years of age [Citation1]. It has been estimated that 81,180 new cases of bladder cancer will be diagnosed by the end of 2022, and 17,100 patient deaths will be attributed to bladder cancer in the same year [Citation2]. The majority of bladder cancer cases (90%) have urothelial carcinoma (UC) histology, which originates in urothelial cells in the bladder or other parts of the urinary tract [Citation3]. Metastatic or unresectable locally advanced (LA) UC, here discussed as advanced UC (aUC), is present in nearly 20% of all invasive UC cases worldwide and is usually fatal [Citation4]. Typically, the prognosis for aUC is poor: the 5-year survival rate for aUC patients is less than 15% [Citation5]. Furthermore, aUC is also associated with major morbidity and a significant economic burden borne by both payors and patients, and also includes lost productivity, transportation, lodging and treatment-related costs [Citation6]. In a recent study conducted in a US managed care environment, researchers found that patients with aUC experienced a median of 72.5 outpatient visits and incurred median all-cause medical costs of US$76,952 per patient per year [Citation7]. In addition, adverse effects associated with therapy for aUC can result in significant burden to patients, families and healthcare systems [Citation8].

The treatment of LA or metastatic UC has evolved in recent years [Citation9,Citation10]. Platinum-based chemotherapy (PBCT) is the standard first-line (1L) treatment for patients with unresectable LA or metastatic UC [Citation11]. However, a rapidly evolving treatment paradigm has improved the prognosis for the typical patient, with the uptake of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), including PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors, providing more treatment options for patients [Citation12]. About 2 years ago, avelumab (anti-PD-L1) was approved by the US FDA as 1L switch maintenance treatment following disease control with the standard of care, PBCT, demonstrating a benefit in overall and progression-free survival with a tolerable safety profile [Citation13,Citation14]. This strategy is now considered standard of care according to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines and several other international guidelines [Citation15,Citation16]. Atezolizumab and pembrolizumab are FDA approved in the 1L setting as monotherapy for those who are ineligible to receive PBCT [Citation17,Citation18]. Atezolizumab is also FDA approved for cisplatin-ineligible patients with PD-L1-high tumors (Ventana SP142 assay).

Each therapy regimen for aUC offers unique clinical profiles in terms of efficacy, potential adverse events, dosing frequency and administration logistics for patients. Selecting a treatment strategy involves carefully balancing considerations of evidence/data, rationale, benefits and risks for each option. Although guidelines recommend that 1L regimens should be chosen mainly based on level of evidence and efficacy and tolerability criteria, there are many other factors that influence therapeutic choice in the context of physician–patient shared decision making: institutional care pathways, patients’ beliefs and expectations, preferences for treatment goals, optimization of treatment adherence and compliance, distance from the cancer center, frequency of therapy administration and monitoring and management of adverse events. The increase in available treatments has created a need to better understand oncologists’ and patients’ preferences surrounding the use of various ICI-based regimens in the 1L treatment of aUC and identify areas of potential misalignment. The goals of this study were to determine oncologists’ and patients’ preferred attributes of 1L treatment for aUC, to quantify the importance of specific treatment attributes and to explore alignment between groups.

Materials & methods

A discrete choice experiment (DCE) design was used to quantify treatment preferences, asking participants to choose between two competing hypothetical treatments with different attributes in a series of questions determined by a statistically optimal experimental design [Citation19,Citation20]. DCEs are commonly used to quantify the strength of consumer preferences for goods or services in markets where choices cannot be observed. This is often the case for healthcare markets and cancer treatments [Citation19–22]. An additional benefit of a DCE is that it allows us to explore preferences for attributes associated with other hypothetical treatments, such as treatment regimens that have not been tested or are currently being tested but have not yet entered the market.

Study design & participant selection

Sample size was determined based on power calculations [Citation23,Citation24] incorporating estimates of the number of DCE questions analyzed (24), the choice probability (0.10), the margin of error (0.10) and confidence level. Based on a confidence level of 95%, we estimated a minimum sample size of 147 patients was required to reach a power of 90%. The web-based survey was provided to 151 medical oncologists and 150 patients with UC in the USA. A third-party vendor contacted potential oncologists from a national database of clinicians and contacted patients via proprietary panels of oncology providers. All recruitment was double-blinded and carried out in accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act guidelines.

Medical oncologists were eligible if they: practiced in the USA for at least 5 years at the time of survey completion; spent ≥50% of their effort in treating or managing patients; were board certified in oncology; treated or managed ≥1 patient with aUC per month; and gave informed consent. Patients were eligible if they: were told by a provider that they had UC; were aged 18 years or older; and gave informed consent. Patients were not limited to those with advanced or metastatic cancer given the likely difficulty in recruiting a sufficient sample size for this study as well as the challenge with clinical stage ascertainment.

The study protocol and materials were reviewed by a central institutional review board, Advarra Institutional Review Board, where the project was deemed exempt from full review (protocol number 00046328). The oncologist and patient recruitment occurred after the central institutional review board deemed this study to be exempt. The participants were asked to provide informed consent upon recruitment.

Survey instrument

The survey instrument was designed in accordance with best practices as described in the DCE literature and endorsed by the International Society of Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) Conjoint Analysis Good Research Practices Task [Citation25–27]. For this study, the DCE was developed to elicit preferences that could then be used to understand the relative importance of attributes of 1L aUC treatments to patients and providers.

First, attributes were selected based on a targeted review of the literature and refined based on input gathered from in-depth interviews conducted with oncologists. The study team reviewed DCEs conducted in UC and other solid tumors to identify attributes common to oncology DCE, as well as studies in UC discussing patient-reported outcomes collected in clinical trials and survey response data [Citation14,Citation25,Citation28–41]. The list of attributes generated through the targeted literature search was confirmed through semi-structured in-depth interviews with oncologists to identify the attributes they consider when making treatment decisions as well as the attributes they think are of interest to their patients.

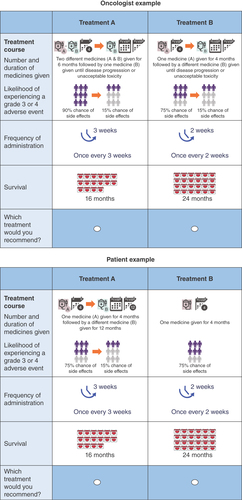

Second, consistent with the ISPOR guidelines [Citation29], we identified all possible current 1L aUC treatment options (whether approved for marketing or in clinical development) in order to guide attribute selection and to determine the attribute levels (Supplementary Table 1) [Citation14,Citation23–25,Citation36–40,Citation42–53]. The duration of treatment for 1L aUC involves an induction phase and maintenance phase for some treatments, while other treatments involve only one treatment during the entire 1L duration. Because of these different phases and durations, the best way to represent the safety profile of each potential treatment option is to define the treatment regimen phases along with their corresponding grade 3/4 treatment-related adverse effects (TRAEs). We used clinical trials that reported TRAEs for chemotherapy only, ICI only, and chemotherapy and ICI in combination to determine TRAEs for the respective treatments and trial phases. We then took those results and mapped them back to the hypothetical treatment profiles, as shown in .

Table 1. Treatment profiles.

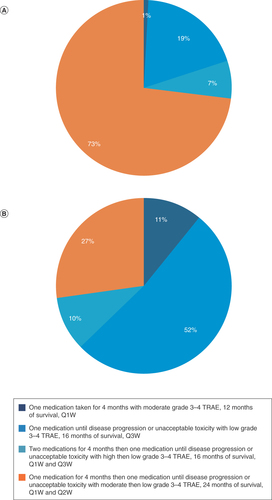

The final three attributes selected for inclusion were overall survival (OS), frequency of dosing and composite treatment experience. The composite treatment experience attribute included the number of medicines received during each phase and their respective durations, as well as the likelihood of experiencing grade 3/4 TRAEs during the phase. lists the descriptions of the four categorical levels for the composite treatment experience attribute, represented by r1, r2, r3 and r4. For example, the r1 level represents ‘one medication taken for 4 months with moderate grade 3/4 TRAEs’ while the r2 level represents ‘one medication until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity with low grade 3/4 TRAEs’.

Table 2. Treatment attributes and levels.

Each attribute had three to four levels, which would vary for each choice set in the DCE. The levels were determined so that the range would encompass the clinically relevant outcomes that were observed in clinical trials and real-world studies in the targeted literature review. The description of the regimens was designed to reflect clinical guidelines or clinical trial descriptions of how a treatment course would be described to a physician. The composite treatment experience was described to continue until progression or an unacceptable level of toxicity. During pilot tests for patients, there were some issues with understanding the length of time description. To reduce potential issues about treatment timing for patients, the description of the regimen was simplified to a set number of months. Specifically, we set the number of months to coincide with the survival months so that the total duration of being on a regimen did not exceed the expected survival months.

Pilot tests were conducted with both patients and oncologists. Eight participants were recruited for the pilot tests: five patients with stage IV bladder cancer and three oncologists. Pilot study participants were invited by the survey vendor to participate in an online pilot testing session, during which participants were asked to explain how they interpreted each question as they read the question and explain the rationale for each answer selection. The survey was adjusted based on the feedback from the pilot test. Our final attributes and levels include OS (12, 16 and 24 months), frequency of dosing (once every week [Q1W], once every 2 weeks [Q2W], once every 3 weeks [Q3W] and once every 6 weeks [Q6W]) and a composite treatment experience, which includes how many medicines patients will take in a given phase, for how long and the associated TRAEs for each phase. The attributes and levels are presented in , with providing example choice tasks for physicians and patients.

The survey also included questions regarding physician screening to confirm respondent eligibility, informed consent and questions regarding background to confirm oncologist practice characteristics or patient’s clinical/demographic information.

Experimental design

In each question, participants were asked to choose between two alternative hypothetical treatments. There was no ‘opt-out’ or ‘neither’ option included, because nontreatment is not an option in the NCCN Clinical Practice Guideline for 1L bladder cancer treatment [Citation15].

The DCE design was created in R using the AlgDesign package [Citation54]. We used D-efficiency criteria in the fractional factorial design [Citation55,Citation56]. The full design included 24 choice tasks that were divided into two blocks of 12 choice tasks. Each respondent was randomly assigned to one of the two blocks of 12 questions.

Statistical analysis

The DCE was designed to allow the estimation of the main-effect preference weights using a random-parameters logit model [Citation27,Citation57]. The random-parameters logit model allows preferences to vary from one individual to another and estimates preference weights, which are the relative measure of the importance of the preference. The random-parameters logit model takes into account unobserved factors that may result in parameters that vary across observations, such as age, disease stage, prior resection, comorbidity profile, performance status and insurance status. More important attributes have a bigger difference in utility across attribute levels: a larger difference indicates that a higher prevalence in certain treatment attributes increases the respondent’s desire to pick that treatment. Likewise, having less of the attribute causes the respondent to choose the other treatment. All attribute levels were effects coded (effects coding yields a unique coefficient for each attribute level included in the study).

Finally, the preference weights were used to obtain the conditional relative attribute importance and preference shares. A preference share is the predicted probability that the average respondent would select a specific treatment profile from among a set of treatment profiles. The profiles for which preference shares were estimated are presented in . The treatment profiles were constructed using the outcomes from the targeted literature search to create profiles that represent specific treatments of interest.

Results

Study sample

Oncologist characteristics are reported in . Among the 151 oncologists surveyed, the median age was 50 years and 72.2% were male; 45.7% of oncologists reported that less than 10% of their patients were currently on Medicaid (). Of their places of work, 78.9% of the oncologists reported they worked at either a group practice or partnership, a government entity, university or comprehensive care center or a specialty group practice; 121 (80.2%) of the oncologists had been in practice for at least 11 years.

Table 3. Oncologist characteristics.

Patient characteristics are reported in . Among the 150 patients surveyed, the median age was 57 years. The majority, 70.7%, was male and 78.7% were Caucasian; 79.4% of patients surveyed reported that they had been diagnosed with bladder cancer for more than 1 year. When asked about the stage of their bladder cancer at diagnosis, a third of patients reported being initially diagnosed with stage II bladder cancer, 20% with stage III and 25.3% with stage IV. However, only 6% reported currently having stage II cancer; most patients reported currently having stage III (39.3%) or stage IV (48.7%) disease.

Table 4. Patient characteristics.

Preference weights

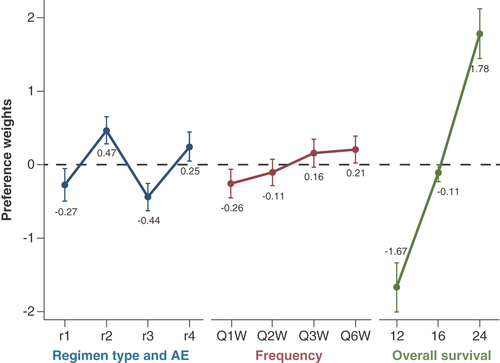

The preference weights for oncologists are presented in . If the CIs for any pair of levels within attributes do not overlap, the preference weight estimates are statistically significant at the 5% level [Citation58]. Within the composite treatment experience attribute, oncologists preferred r2 the most, while preferring r3 the least. Looking at the statistical differences, oncologists were indifferent between r2 and r4. They were also indifferent between r1 and r3. For the frequency of dosing attribute, oncologists were indifferent between Q2W, Q3W and Q6W. A frequency of Q6W was preferred to Q1W.

See Table 2 for the definitions of r1, r2, r3 and r4 for the patients.

AE: Adverse event; Q1W: Once every week; Q2W: Once every 2 weeks; Q3W: Once every 3 weeks; Q6W: Once every 6 weeks.

When comparing across attributes, oncologists demonstrated the strongest preference for OS, with an increase in OS from 12 months to 24 months associated with an increase in utility by 3.454. Frequency of administration had the smallest change in utility, 0.463, when changing from Q1W to Q6W, indicating that frequency of administration is the least important attribute for oncologists. Finally, the composite treatment experience had a utility change of 0.744 when moving from the most preferred level of r2 to the least preferred level of r3.

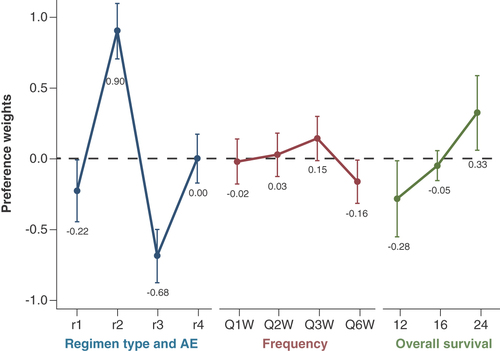

The preference weights for patients are presented in . Within attributes, patients preferred higher OS over lower OS. For the composite treatment experience attribute, patients preferred r2 the most and r3 the least. Patients preferred r2 much more than r4 and were indifferent between r1 and r4. Patients were also indifferent between frequency levels of Q1W, Q2W, Q3W and Q6W. However, the point estimate for Q6W indicates that Q6W was least preferred.

See Table 2 for the definitions of r1, r2, r3 and r4 for the patients.

AE: Adverse event; Q1W: Once every week; Q2W: Once every 2 weeks; Q3W: Once every 3 weeks; Q6W: Once every 6 weeks.

When exploring the importance of attributes to patients, utility changed by 0.604 when moving from 12 months of OS to 24 months. For the composite treatment experience attribute, utility changed by 1.584 when moving from the most preferred level (r2) to the least preferred level (r3). The frequency of administration was associated with the smallest change in utility of only 0.318 when moving from Q6W to Q3W. The composite treatment experience appeared to have the largest influence on patient treatment decisions.

Preference share

To further understand how the preferences exhibited may affect treatment choice, preference shares were estimated and reported in based on treatment profiles presented in .

Q1W: Once every week; Q2W: Once every 2 weeks; Q3W: Once every 3 weeks; Q6W: Once every 6 weeks; TRAE: Treatment-related adverse event.

With OS as the most important attribute for oncologists, a treatment regimen of 4 months of 1L chemotherapy (Q1W) followed by 1L ICI switch maintenance therapy (Q2W) with 24 months of OS was preferred over other evaluated regimens, commanding 73.4% of the preference share. Four months of 1L chemotherapy (Q1W) with 12 months of OS gathered 1% of the preference share and thus was the least preferred. The treatment regimen of 1L ICI monotherapy (Q3W), with 16 months of OS, had the second-highest preference share of 19%, and the remaining 7% fell to the treatment regimen of 1L ICI and chemotherapy together (Q1W + Q3W) followed by ICI maintenance, with 16 months of OS.

For patients, the primary decision driver appeared to be the attribute that describes the patient’s experience with the composite treatment course (number of medicines, length of regimen, grade 3/4 TRAEs). Thus, the largest share of preferences was for the treatment like 1L ICI monotherapy with 16 months of OS (52%). Treatment like 1L chemotherapy followed by 1L ICI maintenance was the second most preferred treatment, at 27%. Treatment like 1L ICI and chemotherapy together followed by ICI maintenance was the least preferred, at 1%.

Discussion

This study quantified the treatment preferences of US oncologists and patients with UC across different levels of three attributes related to the treatment of UC using DCE. DCE is a well-established methodology for quantifying preferences for specific attributes of treatment while making sure that external influences do not alter the decision. Both physicians and patients appeared to prefer treatment attributes related to OS, TRAEs and the number and duration of the medications in a regimen over frequency of administration. However, physicians demonstrated a relatively greater preference for efficacy, while patients exhibited a greater preference for the composite treatment experience, which included the number and duration of medications in a regimen and associated TRAEs. This finding is in alignment with previous DCEs, which have found that these two attributes are often also important in treatment decisions [Citation41].

The results of this study provide informative insights that can help guide clinical conversations, treatment recommendations and guideline development. The apparent divergence in preferences between patients and providers should be seen as an opportunity to improve clinical care and communication in an effort to materialize informed shared decision making. This piece of information may help guide oncologists in their discussions with patients about potential treatment options and their relative advantages and disadvantages vis-à-vis the characteristics studied herein. The advantage of the DCE methodology applied in this context is that it quantifies specifically which attributes are driving treatment choice and preference, and it enables a clear juxtaposition between the desires of patients and the clinical priorities of oncologists.

One important clinical ramification of these results is the importance of the patient experience related to the number and duration of medications in a regimen and their associated TRAEs. In these hypothetical scenarios, patients exhibited a stronger preference for these characteristics of a treatment regimen related to number and duration and TRAEs as more important than improved OS. These characteristics are common among treatment regimens in the real world, as is the trade-off among them compared with OS. Further study is necessary to tease out the specific elements of this composite treatment experience attribute that drive patient preferences; however, real-world treatment options may not exist with each single characteristic in a vacuum, making it challenging to disintegrate this attribute into its components separately. Although this has always been of paramount clinical importance, these results underscore the need to improve treatment protocols, clinical practices and communication patterns to ensure that patients are going to be satisfied with their experience.

With the approval of avelumab for 1L switch maintenance treatment of patients with LA or metastatic UC that has not progressed after 1L PBCT, 1L ICI switch maintenance therapy is now the standard of care under the NCCN and other international treatment guidelines for UC [Citation15,Citation16], suggesting convergence among providers on the best approach for treating patients. The results of this study suggest that patients place high importance on the entire treatment experience, especially for a simplistic regimen with only one medication and low rate of grade 3/4 TRAEs. However, at the individual level, certain patients may place more importance on survival, while others may place more importance on adverse effects [Citation59].

Given the nature of certain aUC treatments involving switching and different levels of AEs during different phases, understanding the treatment course can be daunting to the patient. Misalignment between patients and providers on treatment preferences is not uncommon [Citation60] but underscores the importance of clear communication between physicians and patients. Shared and informed decision making between physicians and patients helps align treatment goals as the disease progresses and the treatment landscape evolves. As is often the case in clinical conversations, patients will benefit from accurate and objective information from their provider about their diagnosis and prognosis. Patients benefit from discussions about their potential treatment journey, expected duration and outcomes and AE management. Psychological support throughout treatment is critical and can help provide encouragement to persevere, for example, communicating the evidence on the impact on patients’ health-related quality of life in addition to impact on survival [Citation61]. Proper patient education that is customized based on their individual characteristics can help to communicate specific treatment options and objective information regarding the course of treatment for aUC; this can influence adherence to a proposed treatment course.

This study has several inherent limitations that merit discussion. First, to address the uniqueness of sequential-type therapies available for the treatment of aUC, potential TRAEs were calibrated based upon clinical trials that matched all potential treatment phases and subsequently mapped back to the actual real-world regimen design. Since the treatment design informed the TRAEs, they are correlated by construction and were presented together. This was a necessary step to reflect the actual patient experience with the treatment regimen more accurately. However, the limitation is that it prevented an estimation of preference weights for grade 3/4 TRAEs, number of medicines or the length of regimen, separately. Survey recruitment was based on convenience and not a priori demographic or clinical characteristics. Patients in this study were relatively young compared with typical patients with aUC, possibly due to the survey being web-based. In addition, our sample likely lacked a significant number of end-stage patients. For example, 39.3% of patients presented with a potentially curable stage III compared with 48.7% with stage IV. These patients may have different preferences such as a stronger preference for survival compared with fewer AEs [Citation62]. The data for current stage and stage at diagnosis that are presented in were ascertained from the clinical questionnaire. Because this information was self-reported, it is possible that patients incorrectly recalled their stage. Likewise, there are limitations associated with the oncologists who participated. It is possible that some oncologists had little experience of treating end-stage aUC. Although >80% of oncologists surveyed had >10 years of experience, this does not guarantee significant experience with aUC. Conclusions should be interpreted with this limitation in mind. As a result, the findings may not reflect the general UC patient or provider population but rather the types of patients and oncologists who were invited and decided to participate (selection/responder bias). A similar study conducted in a sample with different patient characteristics (race/ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic status, etc.) or provider characteristics (community, academic, MD/DO, advanced practice provider, nurse, etc.) may result in different conclusions. The study findings may also not be generalizable to oncologists or patients with other types of cancer or earlier stages of UC. As with any DCE, to keep the survey tractable, we included only the important attributes relevant to the study and we were unable to account for all possible attributes associated with the treatment regimens. It is possible that other attributes would be important to patients or providers, along with several potential confounders. Finally, the questions presented in the survey represent hypothetical scenarios to respondents, and not all these scenarios may be present in practice today.

When presented with the option, patients preferred aUC treatments that reflect a better treatment experience with respect to the number and duration of medications and associated TRAEs, compared with OS benefit or a more convenient administration frequency. In contrast, oncologists exhibited a strong preference for treatments that improve OS over other attributes. As a result, patients preferred treatments with attributes similar to those like upfront 1L ICI monotherapy, whereas oncologists preferred attributes similar to treatments like 1L chemotherapy followed by 1L ICI switch maintenance therapy, which is the current standard of care and the preferred therapy in UC clinical guidelines. Overall, the results of this study provide insightful information that may be beneficial for mutual understanding and alignment on the expectations of treatment. The apparent divergence in preferences between patients and providers can be seen as an opportunity to improve communication and exchange in a model that promotes informed and shared decision making.

Conclusion

While 1L platinum-based chemotherapy followed by 1L ICI maintenance therapy is now the standard of care for aUC based on strength of evidence, efficacy and tolerability, other factors influence therapeutic choice and perception in the context of physician–patient informed, shared decision making. This DCE was designed to address the relative preferences for these treatment attributes by surveying 151 oncologists and 150 patients to evaluate their perspective. Results show that oncologists and patients differ in the types of treatment attributes they prefer. The findings highlight differences in perspective and encourage further discussions between providers and patients about the types of available treatments, the level of evidence, efficacy, safety/toxicity, guidelines and provider’s recommendations, as well as patient preferences, expectations, beliefs and wishes. The results may help providers understand the attributes that patients consider important when discussing treatment options. This may result in better communication between oncologists and patients about the goals and rationale of therapy, available evidence (including quality of life and patient-reported outcomes), logistics, benefits, risks and potential financial burden associated with different options. The results provide a snapshot of preferences from the patient and provider perspectives that can be meaningful within the context of the limited sample design but should not be interpreted as reflecting all patients or oncologists. Despite these limitations, this research provides important insights into the relative preferences for relevant treatment attributes that are important to oncologists and patients, and, if used appropriately, may encourage better mutual understanding and shared decision making as the treatment landscape continues to evolve.

The goal of this descriptive study was to explore which treatments oncologists and patients prefer for treatment of advanced urothelial carcinoma, what factors drive those preferences and whether those preferences align.

A discrete choice experiment was administered to 151 oncologists who treat patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma and 150 patients with urothelial carcinoma (regardless of advanced stage).

For oncologists, overall survival was the most important factor.

Oncologists preferred treatments such as first-line chemotherapy followed by immune checkpoint inhibitor maintenance therapy.

For patients, the composite treatment experience was the most important factor, including number and duration of treatments and associated treatment-related adverse effects.

Patients preferred treatment strategies such as first-line immune checkpoint inhibitor monotherapy.

Results of this study showed that there can be divergence in preferences of treatment attributes between patients and providers.

This study highlights the necessity to improve the communication and exchange of information between patients and providers regarding available treatments in the relevant clinical setting.

Author contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to this research, including the conception, study design, execution, acquisition and analysis of data. All authors took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article, and gave final approval of the version to be published.

Ethical conduct of research

The study protocol and materials were reviewed by an Advarra Institutional Review Board and were determined to be exempt from full review (protocol number 00046328). All survey participants provided informed consent.

Infographic

Download PDF (125.9 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank B Hauber and M Kirker of Pfizer for critical review and feedback that greatly improved the manuscript.

Supplementary data

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This study was conducted under a research contract between PRECISIONheor and Merck (CrossRef Funder ID: 10.13039/100009945). This study was funded by Merck as part of an alliance between Merck and Pfizer. P Grivas has served in consulting or advisory roles for 4D Pharma PLC, Aadi Bioscience, Astellas Pharma, AstraZeneca, Boston Gene, Bristol Myers Squibb, CG Oncology Inc., Dyania Health, Exelixis, Fresenius Kabi, G1 Therapeutics, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Guardant Health, Infinity Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Lucence Health, Merck, Mirati Therapeutics, MSD, Pfizer, PureTech, QED Therapeutics, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Roche, Seattle Genetics, Silverback Therapeutics, Strata Oncology, UroGen; and has received institutional research funding from Bavarian Nordic, Bristol Myers Squibb, Clovis Oncology, Debiopharm Group, G1 Therapeutics, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Mirati Therapeutics, MSD, Pfizer, QED Therapeutics. P Veeranki was an employee of PRECISIONheor at the time of analysis. K Chiu is an employee of PRECISIONheor. V Pawar is an employee of EMD Serono, Inc., Rockland, MA, USA, an affiliate of Merck KGaA. J Chang is an employee of Pfizer. M Bharmal is an employee of EMD Serono, Inc., Rockland, MA, USA, an affiliate of Merck KGaA. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Medical writing support was provided by A Thippeswamy and J Ratcliffe of Clinical Thinking and funded by Merck and Pfizer.

References

- American Cancer Society . Key statistics for bladder cancer (2022). www.cancer.org/cancer/bladder-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

- Siegel RL , MillerKD, FuchsHE, JemalA. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin.72(1), 7–33 (2022).

- American Society of Clinical Oncology . Bladder cancer (2021). www.cancer.net/cancer-types/bladder-cancer/introduction

- Svatek RS , Siefker-RadtkeA, DinneyCP. Management of metastatic urothelial cancer: the role of surgery as an adjunct to chemotherapy. Can. Urol. Assoc. J.3(4 Suppl. 6), S228–S231 (2009).

- Dietrich B , SrinivasS. Urothelial carcinoma: the evolving landscape of immunotherapy for patients with advanced disease. Res. Rep. Urol.10, 7–16 (2018).

- Aly A , JohnsonC, YangS, BottemanMF, RaoS, HussainA. Overall survival, costs, and healthcare resource use by line of therapy in Medicare patients with newly diagnosed metastatic urothelial carcinoma. J. Med. Econ.22(7), 662–670 (2019).

- Kearney M , EspositoD, RussoLet al. Locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma in the United States: economic burden and healthcare utilization. Value Health21, S45 (2018).

- Grivas P , DersarkissianM, ShenolikarR, LaliberteF, DolehY, DuhMS. Healthcare resource utilization and costs of adverse events among patients with metastatic urothelial cancer in USA. Future Oncol.15(33), 3809–3818 (2019).

- Martini A , RaggiD, FallaraGet al. Immunotherapy versus chemotherapy as first-line treatment for advanced urothelial cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat. Rev.104, 102360 (2022).

- Niglio SA , JiaR, JiJet al. Programmed death-1 or programmed death ligand-1 blockade in patients with platinum-resistant metastatic urothelial cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Urol.76(6), 782–789 (2019).

- Dietrich B , Siefker-RadtkeAO, SrinivasS, YuEY. Systemic therapy for advanced urothelial carcinoma: current standards and treatment considerations. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book38(38), 342–353 (2018).

- Lavoie JM , SridharSS, OngMet al. The rapidly evolving landscape of first-line targeted therapy in metastatic urothelial cancer: a systematic review. Oncologist26(8), e1381–e1394 (2021).

- Bukhari N , Al-ShamsiHO, AzamF. Update on the treatment of metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Sci. World J.2018, 5682078 (2018).

- Powles T , ParkSH, VoogEet al. Avelumab maintenance therapy for advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med.383(13), 1218–1230 (2020).

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network . Bladder cancer V1.2022 (2021). www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/bladder.pdf

- Powles T , BellmuntJ, ComperatEet al. Bladder cancer: ESMO clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol.33(3), 244–258 (2022).

- Parikh RB , FeldEK, GalskyMDet al. First-line immune checkpoint inhibitor use in cisplatin-eligible patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma: a secular trend analysis. Future Oncol.16(02), 4341–4345 (2020).

- Ghatalia P , PlimackER. Integration of immunotherapy into the treatment of advanced urothelial carcinoma. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw.18(3), 355–361 (2020).

- Bolt T , MahlichJ, NakamuraY, NakayamaM. Hematologists' preferences for first-line therapy characteristics for multiple myeloma in Japan: attribute rating and discrete choice experiment. Clin. Ther.40(2), 296–308 (2018).

- De Freitas HM , ItoT, HadiMet al. Patient preferences for metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer treatments: a discrete choice experiment among men in three European countries. Adv. Ther.36(2), 318–332 (2019).

- Feinberg B , HimeS, WojtynekJet al. Physician treatment of metastatic triple-negative breast cancer in the immuno-oncology era: a discrete choice experiment. Future Oncol.16(33), 2713–2722 (2020).

- Mansfield C , NdifeB, ChenJ, GallaherK, GhateS. Patient preferences for treatment of metastatic melanoma. Future Oncol.15(11), 1255–1268 (2019).

- Street DJ , BurgessL, LouviereJJ. Quick and easy choice sets: constructing optimal and nearly optimal stated choice experiments. Int. J. Res. Mark22(4), 459–470 (2005).

- Louviere JJ , HensherDA, SwaitJD, AdamowiczW. In: Stated Choice Methods: Analysis and Application.Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK (2010).

- Hauber AB , GonzalezJM, Groothuis-OudshoornCGet al. Statistical methods for the analysis of discrete choice experiments: a report of the ISPOR conjoint analysis good research practices Task Force. Value Health19(4), 300–315 (2016).

- Bridges JF , HauberAB, MarshallDet al. Conjoint analysis applications in health a checklist: a report of the ISPOR Good Research Practices for Conjoint Analysis Task Force. Value Health14(4), 403–413 (2011).

- Reed Johnson F , LancsarE, MarshallDet al. Constructing experimental designs for discrete-choice experiments: report of the ISPOR Conjoint Analysis Experimental Design Good Research Practices Task Force. Value Health16(1), 3–13 (2013).

- Rao A , PatelMR. A review of avelumab in locally advanced and metastatic bladder cancer. Ther. Adv. Urol.11, 1756287218823485 (2019).

- Nadal R , BellmuntJ. Management of metastatic bladder cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev.76, 10–21 (2019).

- Apolo AB , Cambron-MellottMJ, WillOet al. Patient and caregiver benefit-risk preferences for treatment in advanced urothelial carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol.38(Suppl. 6), 448–448 (2020).

- Liu FX , WittEA, EbbinghausS, DibonaventuraBeyer G, BasurtoE, JosephRW. Patient and oncology nurse preferences for the treatment options in advanced melanoma: a discrete choice experiment. Cancer Nurs.42(1), E52–E59 (2019).

- Macewan JP , Gupte-SinghK, ZhaoLM, ReckampKL. Non-small-cell lung cancer patient preferences for first-line treatment: a discrete choice experiment. MDM Policy Pract.5(1), 2381468320922208 (2020).

- Sun H , WangH, XuNet al. Patient preferences for chemotherapy in the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer: a multicenter discrete choice experiment (DCE) study in China. Patient Prefer Adherence13, 1701–1709 (2019).

- Apolo AB , Cambron-MellottMJ, BeusterienKet al. Medical oncologists' first-line treatment preferences in metastatic urothelial carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol.38(Suppl. 6), 449–449 (2020).

- PDQ Screening and Prevention Editorial Board. , Bladder and other urothelial cancers screening (PDQ®): patient version. In: PDQ Cancer Information Summaries.National Cancer Institute (US), MD, USA (2002).

- Balar AV . Recent clinical trials explore immunotherapies for urothelial carcinoma. Oncology33(4), 132–136 (2019).

- Balar AV , ApoloAB, OstrovnayaIet al. Phase II study of gemcitabine, carboplatin, and bevacizumab in patients with advanced unresectable or metastatic urothelial cancer. J. Clin. Oncol.31(6), 724–730 (2013).

- Balar AV , CastellanoD, O'donnellPHet al. First-line pembrolizumab in cisplatin-ineligible patients with locally advanced and unresectable or metastatic urothelial cancer (KEYNOTE-052): a multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol.18(11), 1483–1492 (2017).

- Balar AV , GalskyMD, RosenbergJEet al. Atezolizumab as first-line treatment in cisplatin-ineligible patients with locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma: a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet389(10064), 67–76 (2017).

- Galsky MD , ArijaJaA, BamiasAet al. Atezolizumab with or without chemotherapy in metastatic urothelial cancer (IMvigor130): a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet395(10236), 1547–1557 (2020).

- Collacott H , SoekhaiV, ThomasCet al. A systematic review of discrete choice experiments in oncology treatments. Patient14(6), 775–790 (2021).

- Train KE . In: Discrete Choice Methods with Simulation.Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK (2009).

- Daly A , DekkerT, HessS. Dummy coding vs effects coding for categorical variables: clarifications and extensions. J. Choice Model21, 36–41 (2016).

- Institute for Clinical and Economic Review . Final evidence report and meeting summary: treatment options for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: effectiveness, value and value based price benchmarks. (1 November 2016).

- Shafrin J , SchwartzTT, OkoroT, RomleyJA. Patient versus physician valuation of durable survival gains: implications for value framework assessments. Value Health20(2), 217–223 (2017).

- Powles T , CsősziT, ÖzgüroğluMet al. Pembrolizumab alone or combined with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy as first-line therapy for advanced urothelial carcinoma (KEYNOTE-361): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol.22(7), 931–945 (2021).

- Galsky MD , PowlesT, LiS, HennickenD, SonpavdeG. A phase 3, open-label, randomized study of nivolumab plus ipilimumab or standard of care (SOC) versus SOC alone in patients (pts) with previously untreated unresectable or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (mUC; CheckMate 901). J. Clin. Oncol.36 (Suppl. 6), TPS539 (2018).

- De Santis M , BellmuntJ, MeadGet al. Randomized phase 2/3 trial assessing gemcitabine/carboplatin and methotrexate/carboplatin/vinblastine in patients with advanced urothelial cancer who are unfit for cisplatin-based chemotherapy: EORTC study 30986. J. Clin. Oncol.30(2), 191–199 (2012).

- Balar AV , GalskyMD, RosenbergJEet al. Atezolizumab as first-line treatment in cisplatin-ineligible patients with locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma: a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet389(10064), 67–76 (2017).

- Powles T , VanDer Heijden MS, CastellanoDet al. Durvalumab alone and durvalumab plus tremelimumab versus chemotherapy in previously untreated patients with unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (DANUBE): a randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol.21 (12), 1574–1588 (2020).

- Galsky MD , NecchiA, SridharSSet al. A phase 3, randomized, open-label, multicenter, global study of first-line durvalumab plus standard of care (SoC) chemotherapy and durvalumab plus tremelimumab, and SoC chemotherapy versus SoC chemotherapy alone in unresectable locally advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer (NILE). J. Clin. Oncol.39 (Suppl. 6), TPS504 (2021).

- Van Der Heijden MS , GuptaS, GalskyMDet al. Study EV-302: A 3-arm, open-label, randomized phase 3 study of enfortumab vedotin plus pembrolizumab and/or chemotherapy, versus chemotherapy alone, in untreated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer. Ann. Oncol.31(Suppl. 4), S605–S606 (2020).

- Galsky MD , MortazaviA, MilowskyMIet al. Randomized double-blind phase 2 study of maintenance pembrolizumab versus placebo after first-line chemotherapy in patients with metastatic urothelial cancer. J. Clin. Oncol.38 (16), 1797–1806 (2020).

- Wheeler RE . AlgDesign. The R project for statistical computing (2004). www.r-project.org/

- Aizaki H , NishimuraK. Design and analysis of choice experiments using R: a brief introduction. Agric. Inf. Res.17 (2), 86–94 (2008).

- Jaynes J , WongWK, XuH. Using blocked fractional factorial designs to construct discrete choice experiments for healthcare studies. Stat. Med.35(15), 2543–2560 (2016).

- Prosser LA . Statistical methods for the analysis of discrete-choice experiments: a report of the ISPOR Conjoint Analysis Good Research Practices Task Force. Value Health19(4), 298–299 (2016).

- Boeri M , PurdumAG, SutphinJ, HauberB, KayeJA. CAR T-cell therapy in relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: physician preferences trading off benefits, risks and time to infusion. Future Oncol.17 (34), 4697–4709 (2021).

- Brockelmann PJ , McmullenS, WilsonJBet al. Patient and physician preferences for first-line treatment of classical Hodgkin lymphoma in Germany, France and the United Kingdom. Br. J. Haematol.184 (2), 202–214 (2019).

- Macewan JP , DoctorJ, MulliganKet al. The value of progression-free survival in metastatic breast cancer: results from a survey of patients and providers. MDM Policy Pract.4(1), 2381468319855386 (2019).

- Powles TB , KopyltsovE, SuPJet al. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) from JAVELIN Bladder 100: avelumab first-line (1L) maintenance + best supportive care (BSC) vs BSC alone for advanced urothelial carcinoma (UC). Ann. Oncol.31(Suppl. 4), S578–S579 (2020).

- Jabbarian LJ , MaciejewskiRC, MaciejewskiPKet al. The stability of treatment preferences among patients with advanced cancer. J. Pain Symptom Manage.57(6), 1071–1079 (2019).