Abstract

Cancer is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in India. Despite recent medical and technological advances, the cancer burden in India remains high and continues to rise. Moreover, substantial regional disparities in cancer incidence and access to essential medical resources exist throughout the country. While innovative and effective cancer therapies hold promise for improving patient outcomes, several barriers hinder their development and utilization in India. Here we provide an overview of these barriers, including challenges related to patient awareness, inadequate infrastructure, scarcity of trained oncology professionals, and the high cost of cancer care. Furthermore, we discuss the limited availability of cancer clinical trials in the country, along with an examination of potential avenues to enhance cancer care in India. By confronting these hurdles head-on and implementing innovative, pragmatic solutions, we take an indispensable step toward a future where every cancer patient in the country can access quality care.

Plain Language Summary

Cancer is a major cause of illness and death in India. Despite advances in medicine and technology, the number of people with cancer remains high and continues to increase. There are big differences in access to necessary medical resources across different regions of the country. This article focuses on the barriers that hinder the development and use of effective cancer treatments in India. We discuss challenges related to patient awareness, inadequate medical facilities, a shortage of trained cancer specialists and the high cost of cancer treatment. Additionally, we explore the limited availability of cancer clinical trials in India and potential ways to improve cancer care in the country. By finding innovative and practical solutions to these challenges, we can take a crucial step toward a future where all cancer patients in India have access to high-quality care.

Tweetable abstract

Breaking barriers in cancer care: our article unveils obstacles to quality care in India–cost, awareness, infrastructure, professional scarcity and clinical trial limitations. We delve into innovative solutions, paving the way for equitable care. #CancerCareIndia #Healthcare

Despite recent medical and technological advances, cancer remains the second leading cause of death globally – a burden disproportionately borne by low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) which account for 70% of cancer-related deaths [Citation1,Citation2]. In the case of India, according to the 2020 WHO report, despite reporting only 1.32 million new cases of cancer compared with 2.28 million in the USA, the number of deaths due to cancer in India was 30% greater (~850,000 vs 610,000 deaths) [Citation3,Citation4]. These numbers bring India's mortality to incidence (MI) ratio to 0.68, compared with 0.38 for high-income countries (HIC) [Citation3–5]. Moreover, India's cancer mortality growth rate is among the highest globally, increasing by an annual rate of 2.48% between 2009 and 2019 [Citation6,Citation7]. The paradoxically low cancer incidence but high mortality rate in India suggests an underestimation of the country's true cancer burden, partly driven by underreporting and poor adoption of early screening [Citation8–10]. This is further evidenced by the high proportion of late-stage cancer diagnoses with around 87% of all cancer cases being detected at advanced stages [Citation11]. For example, data from 58 hospital-based cancer registries in India showed that most lung cancer patients were diagnosed at stage IV [Citation12]. This has been attributed to late presentation, which is due to a low level of awareness in the population and among community physicians, lack of availability and participation in cancer screening programs, limited diagnostic facilities locally, financial constraints and stigma associated with the diagnosis [Citation13]. The situation is exacerbated in rural areas where 69% of the total Indian population resides; patients and families often need to travel long distances to reach a tertiary cancer center, and then have to tackle other related challenges such as finding accommodations and dealing with language and cultural differences [Citation14]. Once diagnosed, advanced-stage cancers are more difficult to treat using conventionally available therapies. Consequently, patients face worse outcomes and higher mortality rates. Overall, these statistics highlight that the cancer burden in India is enormous, deadly and growing rapidly.

The disparity in cancer-related health outcomes in India becomes even more pronounced when considering the regional heterogeneity of India's cancer burden across its diverse states. A 2020 report from the Indian National Cancer Registry Programme highlighted that Northeast India had a higher cancer burden relative to the rest of the country [Citation12]. Compared with the average cancer incidence rate in India (96 per 100,000), Aizawl district of Mizoram had the highest incidence rate for males (269.4) and Papumpare district of Arunachal Pradesh had the highest incidence rate for females (219.8) [Citation3,Citation4,Citation12]. This means that one in four males in Aizawl district and females in Papumpare district will likely develop cancer before age 74 [Citation12]. Aizawl district was also reported to have a cancer mortality rate of 152.7 per 100,000 males which is greater than the average cancer mortality rate in India (62.7) and the USA (85.7) [Citation15]. The high cancer burden in Northeast India – where the populations are largely rural – is likely multifactorial, caused by greater exposure to cancer risk factors (such as tobacco use), low health prevention measures, and limited access to medical facilities. Socioeconomic status has also been associated with the risk and outcomes of various cancers [Citation16,Citation17]. For example, the northern states of India, including Bihar, are among the poorest in the country [Citation18]; Bihar also has some of the highest cancer MI ratios in India at 0.81 and 0.90 for females and males respectively [Citation19]. These regional disparities in cancer burden highlight the growing need to improve access to cancer care and innovative treatments, especially among India's most vulnerable populations.

Despite the severity of the country's cancer burden, innovative treatments that have seen significant success in improving health outcomes in other countries have not been widely utilized in India to alleviate common cancers, including lung cancer which contributes to approximately 8% of India's cancer-related deaths [Citation3,Citation4]. The lung cancer mortality rate has been growing by 3.06% yearly in India between 2009 and 2019 [Citation6]. In contrast, the lung cancer mortality rate in the USA has been steadily declining over the past decade and for non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), mortality rates have been declining faster than incidence rates [Citation20,Citation21]. Besides the success in public health measures such as lung cancer screening and smoking cessation, this may be attributed to – at least partially – the invention and broad adoption of several novel targeted therapies, including EGFR and ALK inhibitors, as well as immune-oncology (IO) drugs in the USA [Citation21]. The median overall survival of real-world NSCLC patients on IO monotherapy was found to be 11.3 months for squamous and 14.1 months for non-squamous NSCLC in the USA, whereas the median overall survival was found to be only 8.8 months among patients treated at a top cancer center in India, a number likely to be even lower when averaged across the country [Citation22,Citation23]. These real-world statistics show that India has not seen the same improvement in NSCLC outcomes compared with the USA, which might be due to – at least partially – the fact that many innovative and effective cancer therapies that have already been invented and approved in other countries are not readily accessible to Indian cancer patients [Citation24,Citation25].

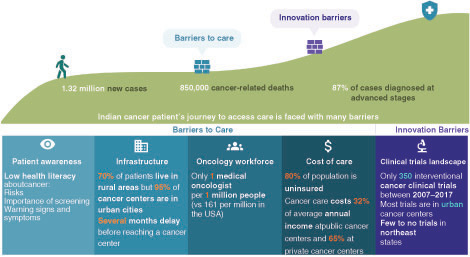

India's enormous and growing cancer burden highlights the need and urgency for introducing effective cancer therapies to improve patient outcomes. There are, however, several barriers at multiple points along the cancer patient's journey that impede the utilization of these therapies ().

Figure 1. Indian cancer patient's journey to access care is faced with many barriers.

According to the 2020 WHO report, 1.32 million new cancer cases and 850,000 cancer-related deaths were reported in India. Around 87% of all cancer cases were detected at advanced stages. Low patient awareness, insufficient medical infrastructure, stretched oncological workforce, and the high cost of cancer treatment contribute to the inaccessibility of basic cancer care. The scarcity of available cancer clinical trials further limits the development of and access to innovative cancer therapies for cancer patients in India.

Barriers & challenges to cancer care in India

Patient awareness/education

As discussed above, one of the contributing factors to India's higher cancer mortality rate is likely delayed diagnoses, which in part may be explained by low cancer awareness and certain cultural norms surrounding healthcare. There is a lack of widespread awareness across communities regarding cancer prevention, risk factors and signs and symptoms, particularly among those of lower education levels and rural inhabitance [Citation26]. There are gaps in knowledge about risk factors that contribute to highly prevalent cancers such as breast cancer, which is the leading cause of new cancer cases among women in India [Citation3,Citation4]. Studies have demonstrated a low health literacy of breast cancer risk factors among Indian women across the socioeconomic spectrum [Citation27]. Furthermore, even though oral cancer is the second most common cancer type in India following breast cancer – and the most common cancer type among men in India [Citation4], in a study investigating rural population's awareness of oral cancer, only 17% of participants could identify the signs of oral cancer [Citation28]. Across common cancers, though tobacco-related cancer risks are relatively well known, there is a lower awareness of how other factors may impact cancer risk including family history, diet, radiation, pollution and hygiene [Citation29]. Low cancer awareness has also fueled misconceptions and inappropriate beliefs that cancer is incurable, transmissible and a form of divine punishment [Citation30]. Female-centered cancers of the breast and cervix are also often stigmatized particularly in rural communities where they manifest as forms of public humiliation, abuse, social isolation, loss of occupation and marital issues [Citation30]. These sociocultural factors in turn may play an adverse role in discouraging some patients from seeking or pursuing screening or preventative measures with the healthcare system.

At the Central level, the government of India has established various educational and screening initiatives to raise awareness and promote early detection of cancer, such as the National Cancer Control Programme which was launched in 1975 [Citation27,Citation31]. The first national cancer screening program in India was launched in 2016 which mandates screening for oral, breast and cervical cancer in people above the age of 30 in 100 districts of India [Citation32]. Despite such efforts, the uptake of screening tests has been slow, with a recent study showing that across the districts of India, the average uptake of cervical screening and breast screening was 22 and 10%, respectively, based on aggregated data from over 699,000 women aged 15–49 years [Citation33]. Additionally, uptake across the diverse regions of the country has been heterogeneous, and many primary preventative measures remain out of reach for many such patients [Citation33]. Low cancer awareness and insufficient proactive health management drive the growing need for culturally targeted, community-based cancer education initiatives in India. This is especially true among rural communities where a lack of resources adds to the challenges faced by patients trying to access cancer care.

Infrastructure

For the average rural patient, the journey to care begins with visiting local primary care centers. These centers are often equipped to provide mostly basic care services and lack access to specialists and diagnostic facilities, leading to multiple referrals to other local facilities, which in turn increases the risk for potential misdiagnoses and inappropriate treatment regimens [Citation13]. Furthermore, even for those rural patients who are ultimately referred to specialist cancer centers for diagnosis or treatment, accessing these centers can still be a huge challenge depending on location. 70% of India's population lives in rural areas but 95% of cancer centers are located in urban cities [Citation34]. The uneven distribution of India's resources and clinical infrastructure is further evidenced by the fact that 60% of specialist cancer centers are located in South and West India even though Northeast India has some of the highest incidence rates of cancer [Citation12,Citation35]. The lack of clinical resources in rural regions and distortion in service provision creates a delay of several months between consultation with a primary care physician and arrival at a cancer center, resulting in disease progression and concerns about the ability to complete treatment regimes [Citation36].

While government-funded, public cancer centers offer subsidized treatments for patients who cannot afford private healthcare, they often lack clinical resources and treatment modalities to support the enormous patient population. A 2021 study analyzing the availability of standard anti-cancer therapies found that LMICs have limited availability of both innovative and core anti-cancer therapeutics, like doxorubicin and cisplatin that are widely utilized in HICs [Citation24]. This is consistent with findings from a 2018 study in New Delhi, which found that the mean availability of essential anti-cancer medicines was only 43% in public hospital pharmacies and 71% in private hospital pharmacies [Citation37]. There is also a critical deficiency in radiotherapy facilities in India, a concerning gap given that around half of all cancer patients will need radiotherapy at some point during their treatment course [Citation38]. As per guidelines from the WHO, India requires 1350 linear accelerator machines to meet patient needs; however, there are only 365 linear accelerators in India as of 2022 [Citation42]. The true depth of this disparity is magnified by the fact that more than 50% of these facilities are housed within private cancer centers that are largely unaffordable and unfeasible for most Indian patients [Citation39]. The consequence of this deficit is that patients may have to wait for up to 1 year before using radiotherapy facilities at public hospitals [Citation39]. The responsibility of counteracting these challenges often falls on the clinical workforce caring for these patients.

Oncology workforce

India has a limited clinical workforce to manage its cancer burden. As of 2018, there was only one medical oncologist per 1 million people in India compared with 161 medical oncologists per 1 million people in the USA [Citation40]. Even among other LMICs, India ranks low in the number of oncologists relative to population [Citation40]. The data reflects the sheer clinical workload endured by Indian medical oncologists contributing to prolonged patient wait times and minimal direct doctor–patient interactions, especially in public cancer centers. Studies have also highlighted a shortage of chemotherapy pharmacists and chemotherapy-administering physicians which could potentially compromise the delivery of high-quality cancer treatment [Citation11]. These factors add to the clinical duties of medical oncologists and limit opportunities to partake in clinical research [Citation41]. In fact, 70% of work time is allocated to clinical duties while only 11% is allocated to clinical research [Citation11]. Clinical research is important for medical oncologists and in-training physicians to understand the care continuum and become familiar with innovative cancer therapies but unfortunately, most of the available oncology training programs in India do not offer structured training in clinical trial methodology, good clinical practice, or drug development [Citation41].

Cost of care

Despite cancer care being nominally less expensive in India compared with the USA, for most Indian cancer patients the costs are extremely high relative to their annual income and are often financed out of pocket (OOP) due to a lack of insurance coverage [Citation42]. The average OOP expenditure per cancer patient is approximately Rs 64,977 (US$818) at public cancer centers and Rs 133,464 (US$1679) at private cancer centers, corresponding to 32 and 65% of the average annual income (Rs 204,000; US$2567) respectively [Citation43,Citation44]. When considering India's skewed wealth distribution, where 57% of the national income is held by the top 10% of the population, it becomes clear that the cost of cancer care is miniscule for a sliver of India's population [Citation44]; meanwhile, for the lower 50% of earners, even basic cancer care can be catastrophically unaffordable. Attesting to this, data has shown that cancer relative to all diseases has the highest catastrophic health expenditure (79%) which is defined as OOP healthcare costs that exceed 10% of household consumption expenditure [Citation45]. Cancer was also reported to have the highest distress financing (43%) which represents situations in which households need to borrow money or sell assets to pay for OOP medical expenses [Citation45]. The issue is further exacerbated by a lack of insurance coverage. Less than 20% of the Indian population is covered under any health insurance scheme [Citation42]. Despite the introduction of government-funded schemes, long reimbursement turnaround times can frontload the cost of care onto patients, pushing them into catastrophic poverty following cancer diagnoses.

Innovative cancer treatments are even more unaffordable in India given that many government reimbursement schemes do not cover such therapies. A study evaluating the coverage of the Vajpayee Arogyashree Scheme, Rajiv Aarogyasri Scheme and Chief Minister Comprehensive Health Scheme found that cancer patients were either not reimbursed or only partially reimbursed for treatment with innovative therapies [Citation46]. For example, Osimertinib, commonly known as Tagrisso, is a US FDA-approved targeted therapy with curative intent for the treatment of advanced or metastatic NSCLC after surgical tumor resection. In the USA, 30 tablets of Osimertinib cost US$17,000, a majority of which is covered by insurance schemes like Medicare [Citation47]. Though the same number of tablets is cheaper in India at US$7000, treatment remains highly unaffordable to most patients due to a lack of insurance coverage [Citation48]. Likewise, there is also a low accessibility of immunotherapies with a study showing that only 2.83% of Indian patients who needed immunotherapy for head and neck or lung cancer actually received it [Citation25]. Accessibility in the low socioeconomic category was found to be even lower at 0.29 versus 6.6% in the high socioeconomic category [Citation25].

Landscape of clinical cancer research in India

Clinical research holds the potential to bring innovative and promising cancer therapies to Indian patients. Despite this opportunity, India, like other LMICs, has a severe shortage of clinical trials with cancer research gaining meager momentum over the past decade. Out of 694 phase III cancer clinical trials published from 2014 to 2017, only 8% were led by LMICs [Citation49]. In the case of India, reports have shown that there were only 350 interventional cancer trials registered on Clinical Trial Registry-India (CTRI) between 2007 and 2017 [Citation50,Citation51]. In contrast, there were 2066 interventional cancer trials in the USA registered on clinicaltrials.gov in 2017 alone [Citation52]. Within India's clinical trial landscape, geographic disparity is prominent. Most cancer clinical trials were concentrated within urban cancer centers in Delhi, Maharashtra, Chandigarh and Puducherry. Northeast India, despite having the highest rates of cancer incidence and mortality, was reported to have few to no ongoing studies between 2007 and 2017 [Citation50].

The scarcity and limited growth of cancer clinical trials in India can be partially attributed to the four aforementioned barriers (patient awareness, infrastructure, oncology workforce and cost of care). For example, a study performed in a Delhi tertiary cancer center found that only 14.82% of patients had knowledge of clinical trials in general [Citation53]. In addition, survey-based studies have shown that cancer patients have preconceived fallacies and misunderstandings fueling conceptions that clinical trial participation will cause harm or abuse [Citation53]. Finally, infrastructural deficiencies as well as a limited oncology workforce capable of conducting clinical trials have also impeded the growth of clinical research in India [Citation13].

Opportunities to enhance cancer care & improve patient outcomes in India

Despite the structural and cultural barriers described above, these current challenges also represent opportunities for intervention that can help inform policy and system-level changes to enhance cancer care in India. Below we describe the strategies to address the aforementioned barriers and highlight recent examples that are successful or promising. A systematic and comprehensive approach to improving cancer care in India would benefit from an interdisciplinary multi-pronged approach.

Raise cancer awareness & implement preventive strategies

Cancer awareness in the general population is crucial for reducing exposure to risk factors for cancer, improving early detection, and promoting better health-seeking behaviors [Citation26]. WHO estimates that between 30 and 50% of all cancer cases are preventable, and that prevention offers the most cost-effective long-term strategy for cancer control [Citation54]. In India, the awareness about cancer risk factors is largely limited to tobacco [Citation26]; it is important to implement nationwide as well as community-based cancer educational programs and/or campaigns to raise awareness of other established cancer risk factors such as alcohol, obesity, infectious and environmental factors, many of which are amenable to prevention [Citation55]. Such programs also provide an excellent opportunity to educate the general public about the importance of cancer screening, the early signs and symptoms of cancer, and how to seek timely and appropriate care. For example, the National Program for Prevention and Control of Cancers, Diabetes, Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke (NPCDCS) has implemented programs to promote healthy behaviors and raise awareness about cancer and available services in the community [Citation56]. The Indian government designated November 7th as National Cancer Awareness Day; on this day, various awareness campaigns are organized across the country to educate the general population about different types of cancer, risk factors, preventive measures and available healthcare services. Several non-government organizations are also working toward raising awareness, promoting cancer screening and early detection and providing patient and family support services [Citation13,Citation57]. To effectively promote cancer awareness, it is crucial to utilize the right communication channels that can maximize reach, for example, through traditional media, social media and community leaders or influencers [Citation58,Citation59]. It's important to introduce early health education in schools; to that end, integrating cancer awareness and prevention modules into the school curriculum can equip the youth with knowledge about cancer, empowering them to contribute to reducing the burden of cancer in the future [Citation60,Citation61].

Promote cancer screening & early detection

Early detection is vital for diagnosing cancer at earlier stages, leading to improved survival and better quality of life for patients. In the past two decades, large-scale randomized controlled trials (RCT) have shown that screening for prevalent cancers in India using simple techniques can significantly reduce the disease burden. For example, periodic examination of the oral cavity can reduce mortality from oral cancer in high-risk individuals (i.e., users of tobacco, alcohol, or both) [Citation62,Citation63]. A single round of screening by testing for human papillomavirus (HPV) was associated with a substantial reduction in the number of advanced cervical cancers and related deaths [Citation64]. Similarly, visual inspection with 4% acetic acid has been demonstrated to reduce the incidence and mortality of cervical cancer [Citation65,Citation66]. Clinical breast examination by primary health workers can detect breast cancer at early stages and in women aged ≥50, reduce mortality by nearly 30% [Citation67]. Collectively, these screening trials included more than half a million people and produced robust evidence that implementing simple screening tests can effectively prevent deaths from common cancers in India [Citation68].

Screening programs for oral, cervical and breast cancers are available in different parts of India through NPCDCS; in addition, population-based cancer screening is being implemented under the National Health Mission as part of comprehensive care, complementing the NPCDCS [Citation69]. Currently, participation in cancer screening in India is very low, with recent data showing that only about 1–2% of the population have ever undergone oral, cervical, or breast cancer screening [Citation69]. In order to implement population-wide cancer screening more effectively in India, it's crucial to address the gaps in integrating screening programs within health systems, provide adequate training to healthcare professionals at primary and community health centers, and focus on infrastructure and workforce development.

In addition to increasing the participation rate in cancer screening, it's crucial to ensure that effective referral mechanisms are in place so that screen-positive cases are diagnosed and treated in a timely fashion. To this end, capturing data and maintaining longitudinal health records of the population from the screening stage onwards can be instrumental in ensuring that screen-positive cases are tracked and followed up appropriately [Citation68].

Leverage technology & invest in building infrastructure & workforce

Investing in building healthcare infrastructure and workforce for cancer care in India is essential to improve patient access to quality care. Such efforts are underway at the national and state level. For example, the government of India, through the NPCDCS, has set in motion plans to establish a number of new rural and urban cancer centers while also remodeling and upgrading existing cancer centers [Citation13]. The initiative also focuses on increasing the number of medical colleges with oncology departments, which can encourage more Indian medical graduates to specialize in oncology. A notable recent development worth highlighting is the establishment of DHR-ICMR Advanced Molecular Oncology Diagnostic Services (DIAMOnDS) in Government Medical Colleges, aimed at providing basic as well as advanced diagnostic services to cancer patients across various regions in India [Citation70]. On the other hand, training and upskilling of primary and community healthcare professionals is also essential, for example, medical social workers should be educated to drive cancer awareness and promote cancer screening in the general population, whereas primary care physicians should be continuously trained to identify and address cancer risk factors, recognize suspected cancer, and initiate referrals promptly. Importantly, standardized and robust referral pathways across all levels of care – from primary care to regional hospitals to tertiary cancer centers – need to be established to ensure the continuity of care and enable timely diagnosis and treatment.

One strategy to highlight is decentralized care, which refers to a model of delivering cancer care services in a distributed fashion with an emphasis on bringing them closer to the patients. In this context, recent technologies such as telemedicine can be leveraged to improve access to care. For example, the ‘ECHO-project' initiative is a collaborative effort between the Tata Memorial Center (TMC) in Mumbai and various rural healthcare providers that connects cancer patients in remote areas with oncologists through teleconsultations; this enables patients to receive expert advice and treatment guidance without the need for travel to a central cancer center [Citation71]. Furthermore, a distributed hub-and-spoke cancer care model that involves centralizing specialized cancer services (e.g., advanced diagnostics, complex treatments and procedures, etc.) in ‘hub’ facilities while extending basic cancer care (e.g., screening, basic diagnostics, patient education, etc.) in ‘spoke' facilities located in surrounding regions or communities could be an effective strategy to improve access to quality cancer care, particularly in areas with limited healthcare resources.

Improve access & affordability of cancer care

Effective and innovative diagnostic tools and treatment options for cancer exist; however, these would not translate to improved patient outcomes at the population level without solving the challenges of access and affordability. Addressing such challenges requires a multi-faceted approach involving a wide range of stakeholders. The Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) has published consensus guidelines on common cancers in India, which should be followed to enable consistent and quality-focused cancer treatment across different settings [Citation13]. From a financial standpoint, the government of India has implemented price control measures on essential cancer drugs; it's important to monitor and regulate drug pricing to ensure that essential cancer medicines are accessible and affordable to the general population. Furthermore, the government of India launched a national public health insurance fund called Ayushman Bharat Yojana (PM-JAY) in 2018 [Citation72]. A substantial step toward increasing access to secondary and tertiary medical care, PM-JAY aims to provide free health insurance to the bottom 50% of India's lowest-income earners for whom cancer care is most inaccessible. The policy provides a sum of INR 500,000 (US$6100) annually per family, an amount that could lessen the catastrophic effects of high-cost cancer care [Citation73]. These initiatives have put India on a promising track toward tackling the issue of the unaffordability of cancer care.

In the case of the more recently developed, innovative cancer treatments (e.g., targeted therapies and immunotherapies), access and affordability remain very limited [Citation25]. Several recent studies showed that at the current reimbursement rate, certain cancer drugs are not cost-effective for use in the Indian context due to the high price, such as immunotherapy agents for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma [Citation74], CDK4/6 inhibitors in the second-line treatment of post-menopausal women with HR+/HER2- metastatic breast cancer [Citation75], and the addition of bevacizumab to the standard chemotherapy for the treatment of advanced and metastatic cervical cancer in India [Citation76]. These studies highlight the need to introduce lower-cost generics and biosimilars in order to bring down the cost of these expensive drugs and make them affordable for Indian patients. In fact, India is emerging as a global leader in the manufacturing and use of generics and biosimilars; many generics and biosimilars have already been approved and used in India for various types of cancer [Citation77]. The incorporation of generics and biosimilars is a feasible cost-cutting strategy to deliver state-of-the-art innovative treatment to patients in developing countries at a cost that's a fraction of the originator drug [Citation78].

Promote clinical cancer research & foster innovation

The distortion of clinical cancer research toward HICs is problematic because the results of these trials may be inapplicable or unsuitable for addressing the cancer treatment needs of patients in India due to epidemiological, infrastructural, socioeconomic, environmental, biological and genetic differences. A fundamental goal of cancer research in India should be to tackle cancers that are common, deadly, or unique to the region, with a focus on identifying practical and accessible treatments.

Collaborations and networks are key to promoting clinical cancer research in India. The National Cancer Grid (NCG) of India was established in 2012, and some of the research-related initiatives of the NCG have been to facilitate the creation of research networks and the establishment of clinical trial units [Citation79]. Noticeably, a clinical trial network in oncology was established in 2020 under the NCG, with the purpose of strengthening the clinical trial capacity across the 11 member centers to promote multi-centric collaborative research in the field of drug and device development [Citation80]. From a capacity-building perspective, the Collaboration for Research methods Development in Oncology (CReDO) workshop has exemplified the merit of global partnerships in clinical research training and has proven to yield improved research output [Citation79,Citation81].

In terms of fostering innovation in clinical cancer research with the aim of developing practical and accessible treatments, one area to highlight is dose de-escalation trials. For example, a recent phase III RCT by Pati V et al., from TMC showed that the addition of an ultra-low dose of an immunotherapy drug nivolumab (6% of the FDA-approved dose) to triple metronomic chemotherapy improved the overall survival of patients with advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma [Citation82]. This trial represents an important step forward toward substantially reducing cost and increasing access to immunotherapy in resource-limited settings [Citation83]. Similar efforts should be explored for other drugs and other cancers. Another area to highlight is drug repurposing, a strategy that seeks new medical treatments from existing, approved medications rather than de novo development of new molecules. Advantages of such an approach include cost–effectiveness, accessibility, known safety profile and rapid implementation. For example, clinical trials developed at CReDO have included drug repurposing trials to test low-cost and/or indigenous drugs like ciprofloxacin for prostate cancer, statins for rectal cancer, chloroquine for glioblastoma, curcumin and metformin for upper aerodigestive tract tumors and esomeprazole in osteosarcoma [Citation79]. At the cutting edge, a third area to highlight is the recent attempts to develop home-grown, cost-effective cellular therapies. India's first indigenously developed Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy has shown promising results in treating lymphoma in a phase I clinical trial led by researchers at TMC in Mumbai and the Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay [Citation84]. Other startups are also working on developing cost-effective and accessible CAR T-cell therapies in India [Citation85].

Since most cancer patients in India have advanced disease and poor performance status at presentation, clinical research on supportive and palliative care is important [Citation86]. Developing evidence-based, cost-effective protocols that focus on improving the quality of life of patients while employing less toxic regimes and involving less demanding follow-up visits would be important and meaningful solutions for cancer patients in the country [Citation13]. Clinical research in supportive and palliative care has led to developments such as Megestrol for cancer cachexia, biophosphonates for pain in bone metastasis, and opioids for the palliation of breathlessness in terminal illnesses [Citation87]. Going forward, it's important to continue promoting clinical research in the field of cancer supportive care, including but not limited to addressing nausea, vomiting and anorexia, in order to better manage symptoms and improve the quality of life for cancer patients.

From a regulatory standpoint, the New Drug Clinical Trial Rules, established in 2019, aim to streamline and facilitate clinical research in India [Citation88]. The rules expedite review and approval processes for nationally and globally funded clinical trials and delineate strict regulations ensuring that clinical trials conducted in India are ethical, safe and of high-quality [Citation88]. In this context, the adoption of standardized and user-friendly clinical trial data aggregation and management programs, along with infrastructure and capacity building, could help expand the reach of clinical trials to sites historically excluded or neglected from participating in such trials. Such innovations hold the promise of implementing distributed clinical trials across a multitude of clinical settings, geographies and the socioeconomic spectrum, which would be essential to enhance the generalizability of clinical trial findings while also offering novel cutting-edge treatment options to patients who would otherwise not have access to such interventions.

Conclusion

India has a considerable cancer burden with growing incidence and mortality rates that are exacerbated by geographical disparities in burden distribution and insufficient clinical resources. Low patient awareness, insufficient medical infrastructure, stretched oncological workforce and the high cost of cancer treatment contribute to the inaccessibility of basic cancer care. The scarcity of available cancer clinical trials further limits the development of and access to innovative cancer therapies with the potential to improve cancer patient outcomes in India, as evidenced elsewhere in the world. Despite these structural and cultural barriers, these current challenges also serve as fertile ground for innovation, offering opportunities for system-level changes to enhance cancer care in India.

Future perspective

The burden of cancer is substantial and growing in India. A significant proportion of cases are being detected at advanced stages, and treatment outcomes of cancer patients in India are significantly poorer than those of other global counterparts. There is hope for improved patient outcomes through innovative and effective cancer therapies, and extensive efforts are currently underway to enhance patient awareness and implement preventive measures, promote cancer screening and early detection, strengthen healthcare infrastructure and workforce and improve access to affordable cancer care. In parallel, collaborations and networks are being established to foster innovative and practical clinical cancer research, aiming to develop cost-effective approaches that address the urgent cancer care needs of the country. The battle against cancer requires concerted efforts from healthcare professionals, researchers, health systems, patients, policymakers and regulators; by adopting a cross-disciplinary, multi-system approach, significant advancements can be made in both clinical research and the delivery of effective, innovative, equitable and affordable cancer care throughout India.

Executive summary

Barriers & challenges to cancer care in India

Patient awareness/education

There is a lack of widespread awareness across communities regarding cancer prevention, risk factors and signs and symptoms, particularly among those of lower education levels and rural inhabitance.

Across common cancers, though tobacco-related cancer risks are relatively well known, there is lower awareness of other factors such as family history, diet and environmental factors.

Low cancer awareness has also fueled misconceptions, including stigma around female-centered cancers.

Infrastructure

India's resources and clinical infrastructure is uneven – 60% of specialist cancer centers are located in South and West India despite the fact that Northeast India has some of the highest incidence rates of cancer.

The lack of clinical resources in rural regions and distortion in service provision creates a delay of several months between consultation with a primary care physician and arrival at a cancer center, resulting in disease progression.

Clinical resources and treatment modalities (such as radiotherapy facilities and availability of both core and innovative anti-cancer therapies) are often lacking in government-funded, public cancer centers, and to a lesser extent, private hospitals.

Oncology workforce

India ranks low in the number of oncologists relative to the population, even among other low- and middle-income countries.

Among medical oncologists in India, 70% of work time is allocated to clinical duties while only 11% is allocated to clinical research.

Cost of care

The cost of cancer care is disproportionately high compared with the annual income of most cancer patients in India.

Innovative cancer treatments are even less accessible and affordable since they are often not reimbursed or only partially reimbursed.

The Landscape of Clinical Cancer Research in India

India has a severe shortage of clinical trials, with only 350 interventional cancer trials registered on Clinical Trial Registry-India (CTRI) between 2007 and 2017.

Within India's clinical trial landscape, the geographic disparity is prominent. Most cancer clinical trials were concentrated within urban cancer centers; Northeast India, despite having the highest rates of cancer incidence and mortality, was reported to have few to no ongoing studies between 2007 and 2017.

The scarcity and limited growth of cancer clinical trials in India can be partially attributed to the four aforementioned barriers (patient awareness, infrastructure, oncology workforce and cost of care).

Opportunities to enhance cancer care & improve patient outcomes in India

Raise cancer awareness & implement preventive strategies

WHO estimates that between 30–50% of all cancer cases are preventable, and that prevention offers the most cost-effective long-term strategy for cancer control.

It's imperative to implement nationwide as well as community-based cancer educational programs and/or campaigns to raise awareness of established cancer risk factors such as alcohol, obesity and infectious and environmental factors, many of which are amenable to prevention.

Examples include the National Program for Prevention and Control of Cancers, Diabetes, Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke (NPCDCS), awareness campaigns on National Cancer Awareness Day and various programs by non-government organizations.

The right communication channels should be used to maximize reach (e.g., traditional media, social media, community leaders or influencers, etc.).

Early education on cancer awareness and prevention should be integrated into the school curriculum to empower the youth.

Promote cancer screening & early detection

Large-scale randomized controlled trials in the past 2 decades have produced robust evidence that implementing simple screening tests can effectively prevent deaths from common cancers in India.

Screening programs for oral, cervical and breast cancers are available in different parts of India through NPCDCS, but implementation in health systems needs to be strengthened.

In addition to increasing the participation rate in cancer screening, it's crucial to ensure that effective referral mechanisms are in place so that screen-positive cases are diagnosed and treated in a timely fashion.

Leverage technology & invest in building infrastructure & workforce

Efforts are underway at the national and state level to invest in building healthcare infrastructure and workforce for cancer care in India.

Standardized and robust referral pathways across all levels of care—from primary care to regional hospitals to tertiary cancer centers—need to be established to ensure the continuity of care and enable timely diagnosis and treatment.

Decentralized care could be an effective strategy to improve access to quality cancer care, particularly in areas with limited healthcare resources.

Improve access & affordability of cancer care

Addressing the issue of access and affordability of cancer care requires a multi-faceted approach involving a wide range of stakeholders.

Consensus guidelines on common cancers in India have been published by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) and should be followed to enable consistent and quality-focused cancer treatment across different settings.

Price control measures on essential cancer drugs are important.

Certain recently developed, innovative cancer treatments are not cost-effective for use in the Indian context at the current reimbursement rate; the incorporation of generics and biosimilars could be a feasible cost-cutting strategy.

Promote clinical cancer research & foster innovation

A fundamental goal of cancer research in India should be to tackle cancers that are common, deadly, or unique to the region, with a focus on identifying practical and accessible treatments.

Collaborations and networks are key to promoting clinical cancer research in India (e.g., the establishment of a clinical trial network in oncology under the National Cancer Grid, the Collaboration for Research methods Development in Oncology, etc.).

A few areas to highlight include dose de-escalation trials, drug repurposing trials, and the recent attempts to develop home-grown, cost-effective cellular therapies for cancer.

Since most cancer patients in India have advanced disease and poor performance status at presentation, clinical research on supportive and palliative care is important.

Standardized and user-friendly clinical trial data programs, along with infrastructure and capacity building, could help expand the reach of clinical trials to historically excluded or neglected sites in India.

Author contributions

N Chintapally, M Nuwayhid and P Gao conceptualized the article, with input from BY Reddy and C Sunkavalli. N Chintapally, M Nuwayhid and P Gao drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to revising the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank J Chen, S Panyam, R Lall, A Majumder and B Chang for reviewing and providing critical feedback on the article. We thank A Auw, L Eun and G Vinces for optimizing the figure for the article.

Writing disclosure

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This work is supported by Pi Health USA, which is a fully-owned subsidiary of BeiGene, Ltd M Nuwayhid, P Gao and BY Reddy are full-time employees of Pi Health USA, which is a fully owned subsidiary of BeiGene, Ltd M Nuwayhid, P Gao and BY Reddy report having received BGNE stock grants for employment. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Cancer Society . Global Cancer Facts & Figures (4th Edition).American Cancer Society, Atlanta, USA (2018).

- WHO, International Agency for Research on Cancer . Estimated number of deaths in 2020, all cancers, both sexes, all ages. Cancer Today. (2020). https://gco.iarc.fr/today/online-analysis-pie?v=2020&mode=population&mode_population=income&population=900&populations=900&key=total&sex=0&cancer=39&type=1&statistic=5&prevalence=0&population_group=0&ages_group%5B%5D=0&ages_group%5B%5D=17&nb_items=7&group_cancer=1&include_nmsc=1&include_nmsc_other=1&half_pie=0&donut=0 (Accessed 14092022).

- Sung H , FerlayJ, SiegelRLet al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin.71(3), 209–249 (2021).

- Global Cancer Observatory . Cancer Today.International Agency for Research on Cancer (2020). gco.iarc.fr/today (Accessed 14092022).

- Gulia S , SengarM, BadweR, GuptaS. National Cancer Control Programme in India: Proposal for Organization of Chemotherapy and Systemic Therapy Services. J Glob Oncol3(3), 271–274 (2017).

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation . https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/

- Global Burden of Disease 2019 Cancer Collaboration . KocarnikJM, ComptonKet al.Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Years of Life Lost, Years Lived With Disability, and Disability-Adjusted Life Years for 29 Cancer Groups From 2010 to 2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. JAMA Oncol8(3), 420–444 (2022).

- Kadam YR , QuraishiSR, DhobleRV, SawantMR, GoreAD. Barriers for Early Detection of Cancer Amongst Urban Indian Women: A Cross Sectional Study. Iran J Cancer Prev9(1), e3900 (2016).

- Tripathi N , KadamYR, DhobaleRV, GoreAD. Barriers for early detection of cancer amongst Indian rural women. South Asian J Cancer3(2), 122–127 (2014).

- Kulothungan V , SathishkumarK, LeburuSet al. Burden of cancers in India - estimates of cancer crude incidence, YLLs, YLDs and DALYs for 2021 and 2025 based on National Cancer Registry Program. BMC Cancer22(1), 527 (2022).

- Sengar M , FundytusA, HopmanWMet al. Medical oncology in India: workload, infrastructure, and delivery of care. Indian Journal of Medical and Paediatric Oncology40(1), 121–127 (2019).

- Mathur P , SathishkumarK, ChaturvediMet al. Cancer Statistics, 2020: Report From National Cancer Registry Programme, India. JCO Glob Oncol6, 1063–1075 (2020).

- Singh M , PrasadCP, SinghTD, KumarL. Cancer research in India: challenges & opportunities. Indian J. Med. Res.148(4), 362–365 (2018).

- Sullivan R , BadweRA, RathGKet al. Cancer research in India: national priorities, global results. Lancet Oncol15(6), e213–222 (2014).

- WCRF International . www.wcrf.org/cancer-trends/global-cancer-data-by-country/

- Williams J , AllenL, WickramasingheK, MikkelsenB, RobertsN, TownsendN. A systematic review of associations between non-communicable diseases and socioeconomic status within low- and lower-middle-income countries. J Glob Health8(2), doi: 10.7189/jogh.08.020409 (2018).

- Finke I , BehrensG, WeisserL, BrennerH, JansenL. Socioeconomic Differences and Lung Cancer Survival-Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Oncol8, 536 (2018).

- Arora A , SinghSP, SiddiquiMZ. The new estimate of India's Multidimensional Poverty. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.32876.87681 (2018).

- India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative Cancer Collaborators . The burden of cancers and their variations across the states of India: the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990-2016. Lancet Oncol19(10), 1289–1306 (2018).

- Siegel RL , MillerKD, FuchsHE, JemalA. Cancer Statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J. Clin.71(1), 7–33 (2021).

- Howlader N , ForjazG, MooradianMJet al. The Effect of Advances in Lung-Cancer Treatment on Population Mortality. N. Engl. J. Med.383(7), 640–649 (2020).

- Waterhouse D , LamJ, BettsKAet al. Real-world outcomes of immunotherapy-based regimens in first-line advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer156, 41–49 (2021).

- Mohan A , GargA, GuptaAet al. Clinical profile of lung cancer in North India: a 10-year analysis of 1862 patients from a tertiary care center. Lung India37(3), 190–197 (2020).

- Fundytus A , SengarM, LombeDet al. Access to cancer medicines deemed essential by oncologists in 82 countries: an international, cross-sectional survey. Lancet Oncol22(10), 1367–1377 (2021).

- Ravikrishna M , AbrahamG, PatilVMet al. Checkpoint inhibitor accessibility in 15,000+ Indian patients. Presented at: ASCO Annual Meeting.Chicago, USA (2022).

- Sahu DP , SubbaSH, GiriPP. Cancer awareness and attitude towards cancer screening in India: a narrative review. J Family Med Prim Care9(5), 2214–2218 (2020).

- Gupta A , ShridharK, DhillonPK. A review of breast cancer awareness among women in India: cancer literate or awareness deficit?Eur. J. Cancer51(14), 2058–2066 (2015).

- Sankeshwari R , AnkolaA, HebbalM, MuttagiS, RawalN. Awareness regarding oral cancer and oral precancerous lesions among rural population of Belgaum district, India. Glob Health Promot23(3), 27–35 (2016).

- Veerakumar AM , KarSS. Awareness and perceptions regarding common cancers among adult population in a rural area of Puducherry, India. J Educ Health Promot6, 38 (2017).

- Nyblade L , StocktonM, TravassoS, KrishnanS. A qualitative exploration of cervical and breast cancer stigma in Karnataka, India. BMC Womens Health17(1), 58 (2017).

- Chalkidou K , MarquezP, DhillonPKet al. Evidence-informed frameworks for cost-effective cancer care and prevention in low, middle, and high-income countries. Lancet Oncol15(3), e119–131 (2014).

- Bagcchi S . India launches plan for national cancer screening programme. BMJ355, doi: 10.1136/bmj.i5574 (2016).

- Monica , MishraR. An epidemiological study of cervical and breast screening in India: district-level analysis. BMC Womens Health20(1), 225 (2020).

- Banavali SD . Delivery of cancer care in rural India: experiences of establishing a rural comprehensive cancer care facility. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol36(2), 128–131 (2015).

- Mallath MK , TaylorDG, BadweRAet al. The growing burden of cancer in India: epidemiology and social context. Lancet Oncol15(6), e205–212 (2014).

- Datta SS , GhoseS, GhoshMet al. Journeys: understanding access, affordability and disruptions to cancer care in India. Ecancermedicalscience16, 1342 (2022).

- Faruqui N , MartiniukA, SharmaAet al. Evaluating access to essential medicines for treating childhood cancers: a medicines availability, price and affordability study in New Delhi, India. BMJ Glob Health4(2), e001379 (2019).

- Burnet NG , BensonRJ, WilliamsMV, PeacockJH. Improving cancer outcomes through radiotherapy. Lack of UK radiotherapy resources prejudices cancer outcomes. BMJ320(7229), 198–199 (2000).

- Gupta M , SinghK. Steps to improve cancer treatment facilities especially radiotherapy infrastructure in India. J Cancer Res Ther18(1), 1–4 (2022).

- Number of oncologists per one million people by select country 2018. www.statista.com/statistics/884711/oncologists-density-by-country-worldwide/

- Saini KS , AgarwalG, JagannathanRet al. Challenges in launching multinational oncology clinical trials in India. South Asian J Cancer2(1), 44–49 (2013).

- Dhankhar A , KumariR, BahurupiYA. Out-of-Pocket, Catastrophic Health Expenditure and Distress Financing on Non-Communicable Diseases in India: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev22(3), 671–680 (2021).

- Singh PK , SinghS. What is the cost of cancer care in India?The Week (2020). www.theweek.in/news/health/2020/02/26/what-is-the-cost-of-cancer-care-in-india.html

- Chancel L , PikettyT, SaezE, ZucmanGet al. World Inequality Report 2022. World Inequality Lab, boulevard Jourdan, PARIS (2021).

- Kastor A , MohantySK. Disease-specific out-of-pocket and catastrophic health expenditure on hospitalization in India: do Indian households face distress health financing?PLOS ONE13(5), e0196106 (2018).

- Haitsma G , PatelH, GurumurthyP, PostmaMJ. Access to anti-cancer drugs in India: is there a need to revise reimbursement policies?Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res18(3), 289–296 (2018).

- Aguiar PN Jr , HaalandB, ParkW, SanTan P, DelGiglio A, de Lima LopesGJr. Cost-effectiveness of Osimertinib in the First-Line Treatment of Patients With EGFR-Mutated Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. JAMA Oncol4(8), 1080–1084 (2018).

- Thakur S , ChakrabortyDS, LahiryS, ChoudhuryS. Osimertinib as an emerging therapeutic modality in nonsmall cell lung cancer: opportunities and challenges in Indian scenario. Lung India37(1), 77–78 (2020).

- Wells JC , SharmaS, DelPaggio JCet al. An Analysis of Contemporary Oncology Randomized Clinical Trials From Low/Middle-Income vs High-Income Countries. JAMA Oncol7(3), 379–385 (2021).

- Chakraborty S , MallickI, LuuHNet al. Geographic disparities in access to cancer clinical trials in India. Ecancermedicalscience15, 1161 (2021).

- Roy AM , MathewA. Audit of Cancer Clinical Trials in India. J Glob Oncol5, 1 (2019).

- National Library of Medicine . https://clinicaltrials.gov/

- Biswkarma VK , RohatgiN, SaxenaR, GuptaSK. Knowledge, attitudes, and perception of 398 cancer patients toward participation in clinical trials: a single-center study from New Delhi, India. Perspect Clin Res13(1), 43–47 (2022).

- WHO . www.who.int/activities/preventing-cancer

- Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce & Industry in collaboration with Ernst & Young Global Limited . https://assets.ey.com/content/dam/ey-sites/ey-com/en_in/topics/health/2022/ey-making-quality-cancer-care-more-accessible-and-affordable-in-india.pdf

- Rath GK , GandhiAK. National cancer control and registration program in India. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol35(4), 288–290 (2014).

- Parashar D . The role of non government organizations in cancer control programmes in developing countries. Indian Journal of Palliative Care10(2), (2004).

- Schliemann D , SuTT, ParamasivamDet al. Effectiveness of Mass and Small Media Campaigns to Improve Cancer Awareness and Screening Rates in Asia: A Systematic Review. J Glob Oncol5, 1–20 (2019).

- Plackett R , KaushalA, KassianosAPet al. Use of Social Media to Promote Cancer Screening and Early Diagnosis: Scoping Review. J Med Internet Res22(11), e21582 (2020).

- Anbazhagan S , ShanbhagD, AntonyAet al. Comparison of effectiveness of two methods of health education on cancer awareness among adolescent school children in a rural area of Southern India. J Family Med Prim Care5(2), 430–434 (2016).

- Budukh A , ShahS, KulkarniSet al. Tobacco and cancer awareness program among school children in rural areas of Ratnagiri district of Maharashtra state in India. Indian J. Cancer59(1), 80–86 (2022).

- Sankaranarayanan R , RamadasK, ThomasGet al. Effect of screening on oral cancer mortality in Kerala, India: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet365(9475), 1927–1933 (2005).

- Sankaranarayanan R , RamadasK, TharaSet al. Long term effect of visual screening on oral cancer incidence and mortality in a randomized trial in Kerala, India. Oral Oncol49(4), 314–321 (2013).

- Sankaranarayanan R , NeneBM, ShastriSSet al. HPV screening for cervical cancer in rural India. N. Engl. J. Med.360(14), 1385–1394 (2009).

- Sankaranarayanan R , EsmyPO, RajkumarRet al. Effect of visual screening on cervical cancer incidence and mortality in Tamil Nadu, India: a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet370(9585), 398–406 (2007).

- Shastri SS , MittraI, MishraGAet al. Effect of VIA screening by primary health workers: randomized controlled study in Mumbai, India. J. Natl Cancer Inst.106(3), doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju009 (2014).

- Mittra I , MishraGA, DikshitRPet al. Effect of screening by clinical breast examination on breast cancer incidence and mortality after 20 years: prospective, cluster randomised controlled trial in Mumbai. BMJ372, doi: 10.1136/bmj.n256 (2021).

- Budukh AM , DikshitR, ChaturvediP. Outcome of the randomized control screening trials on oral, cervix and breast cancer from India and way forward in COVID-19 pandemic situation. Int. J. Cancer149(8), 1619–1620 (2021).

- Gopika MG , PrabhuPR, ThulaseedharanJV. Status of cancer screening in India: an alarm signal from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5). J Family Med Prim Care11(11), 7303–7307 (2022).

- Department of Health Research . https://htain.icmr.org.in/diamonds

- Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes . www.echoindia.in/healthcare

- National Health Authority . https://pmjay.gov.in/about-pmjay

- National Health Authority . https://nha.gov.in/PM-JAY

- Gupta D , SinghA, GuptaNet al. Cost-Effectiveness of the First Line Treatment Options For Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma in India. JCO Glob Oncol9, e2200246 (2023).

- Gupta N , GuptaD, DixitJet al. Cost Effectiveness of Ribociclib and Palbociclib in the Second-Line Treatment of Hormone Receptor-Positive, HER2-Negative Metastatic Breast Cancer in Post-Menopausal Indian Women. Appl Health Econ Health Policy20(4), 609–621 (2022).

- Gupta N , NehraP, ChauhanASet al. Cost Effectiveness of Bevacizumab Plus Chemotherapy for the Treatment of Advanced and Metastatic Cervical Cancer in India-A Model-Based Economic Analysis. JCO Glob Oncol8, e2100355 (2022).

- Chopra R , LopesG. Improving Access to Cancer Treatments: The Role of Biosimilars. J Glob Oncol3(5), 596–610 (2017).

- Natarajan A , MehraN, RajkumarT. Economic perspective of cancer treatment in India. Med. Oncol.37(11), 101 (2020).

- Ranganathan P , ChinnaswamyG, SengarMet al. The International Collaboration for Research methods Development in Oncology (CReDO) workshops: shaping the future of global oncology research. Lancet Oncol22(8), e369–e376 (2021).

- National Cancer Grid . https://tmc.gov.in/ncg/index.php/research/bsnc

- Pramesh CS , BadweRA, SinhaRK. The national cancer grid of India. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol35(3), 226–227 (2014).

- Patil VM , NoronhaV, MenonNet al. Low-Dose Immunotherapy in Head and Neck Cancer: A Randomized Study. J. Clin. Oncol.41(2), 222–232 (2023).

- Mitchell AP , GoldsteinDA. Cost Savings and Increased Access With Ultra-Low-Dose Immunotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol.41(2), 170–172 (2023).

- HindustanTimes . www.hindustantimes.com/cities/mumbai-news/iitbtata-hosp-cancer-therapy-trials-show-promising-results-101662923174819.html

- Burki TK . CAR T-cell therapy roll-out in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Haematol8(4), e252–e253 (2021).

- Damani A , SalinsN, GhoshalAet al. Provision of palliative care in National Cancer Grid treatment centres in India: a cross-sectional gap analysis survey. BMJ Support Palliat Care, doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2019-002152 (2020).

- Khosla D , PatelFD, SharmaSC. Palliative care in India: current progress and future needs. Indian J Palliat Care18(3), 149–154 (2012).

- Annapurna SA , RaoSY. New drug and clinical trial rules, 2019: an overview. Int. J. Clin. Trials.7(4), 278–284 (2020).