Abstract

Aim:

To examine real-world treatment patterns, survival, healthcare resource use and costs in elderly Medicare beneficiaries with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

Methods:

11,880 Medicare patients aged ≥66 years with DLBCL between 1 October 2015 and 31 December 2018 were followed for ≥12 months after initiating front-line treatment.

Results:

Two-thirds (61.2%) of the patients received standard-of-care R-CHOP as first-line treatment. Hospitalization was common (57%) in the 12-months after initiation of 1L treatment; the mean DLCBL-related total costs were US$84,416 during the same period. Over a median follow-up of 2.1 years, 17.8% received at least 2L treatment. Overall survival was lower among later lines of treatment (median overall survival from initiation of 1L: not reached; 2L: 19.9 months; 3L: 9.8 months; 4L: 5.5 months).

Conclusion:

A large unmet need exists for more efficacious and well-tolerated therapies for older adults with DLBCL.

Plain Language Summary

Plain language summary – Older patients with DLBCL need more effective treatments

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common form of Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and it becomes more common with age. While researchers continue to develop newer, more effective treatments for DLBCL, it is important to understand how patients use existing treatments and the associated costs, particularly among the elderly. In our real-world analysis of nearly 12,000 older patients with DLBCL, we found high rates of hospitalization and hospice use, short length of life in later lines of therapy and substantial healthcare costs. Our findings suggest a large current unmet need for more effective and well-tolerated therapies for older adults with DLBCL in both the front-line and relapse/refractory settings.

Tweetable abstract

A real-world analysis of nearly 12,000 elderly patients with DLBCL observed high rates of hospitalization and hospice use, poor overall survival in later lines of therapy and substantial healthcare costs, suggesting a large unmet need.

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), an aggressive type of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL), accounts for approximately 31% of newly diagnosed NHL cases [Citation1]. Survival for patients with DLBCL was poor before the introduction of the current standard first-line (1L) regimen of rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (R-CHOP) [Citation2]. While the intent of 1L treatment is often curative, many patients with DLBCL relapse or become refractory to 1L therapy and may be eligible for second-line and subsequent (2L+) treatment, such as hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) or salvage chemotherapy [Citation3,Citation4]. More recently, newer treatments have also been developed for relapsed/refractory DLBCL, including CAR-T cell therapies, bispecific antibodies, monoclonal antibodies and antibody drug conjugates (ADC).

Given ongoing development of novel therapies in DLBCL, it is important to understand the unmet needs and economic burden in these patients using the most recently available real-world data, particularly in the elderly Medicare population. The few studies that have been conducted in the elderly fee-for-service Medicare population used much older data (ranging from 2000 to 2014) [Citation5–7], primarily focused on relapsed/refractory patients [Citation5,Citation6], and/or relied upon Medicare claims linked with cancer registries limited to data from 18–21 sites in selected states across the USA [Citation5,Citation7].

The lack of more recent and generalizable data in US elderly patients with DLBCL is a major gap in the literature for several reasons. First, DLBCL becomes more common as people age with a median age at diagnosis of 70 years and nearly a quarter of diagnoses occurring in patients >75 years [Citation8]. Second, difficulties remain in optimizing even standard of care treatments for older patients given concerns around potential adverse events [Citation9]. Third, elderly patients with DLBCL also present with more comorbidities than younger patients; comorbidity has been linked with worse overall survival and toxicity in patients with advanced DLBCL treated with R-CHOP [Citation10]. These issues may impact treatment choices and associated healthcare resource use (HRU) and costs for elderly patients with DLBCL in the real-world setting.

The objective of this descriptive study was to examine real-world treatment patterns, survival, HRU and costs in a national sample of elderly Medicare beneficiaries newly diagnosed with DLBCL. This study not only fills a critical gap in the evidence base among elderly patients with DLBCL but also provides baseline data on treatment patterns and outcomes in a high-risk, high-prevalence population immediately prior to the availability of recent novel DLBCL agents. Our findings will be of particular use in comparing real-world outcomes once data accumulates for newer DLBCL agents.

Patients & methods

Study design & data source

This was a retrospective cohort study using 100% Chronic Conditions Warehouse fee-for-service Medicare Part A, B, and D claims data from 2014 to 2019, the latest data available when the analysis was performed. The data contain medical and prescription claims for all fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries in USA. The Medicare claims data are linked to Medicare personal summary files that contain demographic and enrollment information as well as the actual date of death (unlike commercial claims databases, which usually lack mortality information). Further information concerning the data source is available from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Chronic Conditions Warehouse [Citation11].

Study sample

The study population consisted of fee-for-service beneficiaries in the Medicare program, which provides coverage for both elderly (≥65 years) and disabled individuals in the USA. Once a patient become eligible for Medicare they are typically enrolled for life and hence there is relatively little ‘patient churn’ that is frequently seen in US commercial claims data wherein employees may change plans or jobs and hence are lost to follow-up. Besides death and end of the data period, patients in our data source could only be lost to follow-up when they switched to a Medicare Advantage plan (i.e., capitated/HMO plans), as these plans are not included in the Medicare fee-for-service claims database. Newly diagnosed DLBCL patients were identified using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes between 1 October 2015 and 31 December 2018 (Supplementary File 1). The date of first DLBCL diagnosis was defined as the index date and patients were considered newly diagnosed if they did not have any DLBCL diagnosis in the 12-months period prior to the index date. Post-2015 data was used because prior to October 2015, there was no specific ICD-9 code for DLBCL. Patients were included in the sample if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) ≥1 inpatient claim with DLBCL in primary position and/or ≥2 outpatient claims with a diagnosis of DLBCL at least 30 days apart between 1 October 2015 and 31 December 2018; (2) continuous fee-for-service Medicare Part A, B and D coverage for at least 12 months before the index date and 12 months after (or until death) the index date; (3) ≥66 years old on the index date (i.e., the elderly Medicare population) and (4) evidence of a known, identifiable DLBCL-indicated treatment in the frontline setting (Supplementary File 2). We required continuous enrollment for at least 12 months after the index (or until death) in order to have a minimum coverage period to ensure we could capture treatments received after the index date. Further, we did not want to include patients that switched from Medicare fee-for-service insurance to Medicare Advantage early after diagnosis given we lack claims for Medicare Advantage enrollees. Given the 12-month requirement was only a minimum, most patients included in our final sample had more than 12 months of follow-up. Patients were excluded if they (1) had evidence of a claim with a diagnosis of DLBCL in the 12-month pre-index period (to ensure only newly diagnosed patients were included in the sample); (2) had any evidence of anticancer treatment in the 12-month pre-index period; or (3) had evidence of stem cell transplant in the 12-month pre-index period. For the analysis of HRU and costs we additionally required that patients have continuous fee-for-service Medicare Part A, B and D coverage for at least 12 months after (or until death) the initiation date of each specific line of treatment.

Identification of lines of therapy

A claims-based algorithm was used to identify lines of therapy based on previously published administrative claims studies and in consultation with a clinical expert (described in greater detail in Supplementary File 3) [Citation6,Citation7,Citation12,Citation13]. Lines of therapy refers to the treatment regimen and not a specific drug: a line of therapy is made up of one or more drugs (i.e., a patient can be receiving a single drug or a combination regimen). The overall sample was followed from the index date (i.e., new DLBCL diagnosis) until end of study period (i.e., 31 December 2019), death, or censoring (i.e., enrollment into Medicare Advantage [MA] plans since claims data are unavailable for MA plans), whichever occurred earlier to identify the lines of therapy received. To identify a line of therapy, the service date for the first claim for any DLBCL chemotherapy occurring within an individual’s follow-up period was identified. Any other therapies received during or within 30 days of the date of the first fill or infusion identified was considered part of first-line therapy. This length of time is long enough to capture the longest recommended duration of an R-CHOP or rituximab plus dose-adjusted etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin (DA-EPOCH-R) cycle. The principle was the same for subsequent lines of therapy (any therapy occurring during or within 30 days of therapy was considered part of that regimen). Patients were assumed to continue on a line of therapy until one of the following scenarios occurred: (i) initiation of a new therapy not part of the original regimen, (ii) re-initiation of at least one or all of the agents in the first-line treatment regimen following a treatment-free interval of >60 days, or (iii) patient death, entering hospice, or reaching the end of the study period [Citation6,Citation7,Citation12,Citation13].

The patients who have evidence of initiating front-line treatment in the post-index follow-up period were classified as front-line treatment patients. The patients who have evidence of initiating second-line or subsequent line treatments in the post-index follow-up were classified as relapsed/refractory patients. From the relapsed/refractory patient group identified based on initiation of second-line treatment as described above, we further identified subsamples of patients who initiated (a) third-line and (b) fourth-line treatment.

Outcomes

Outcomes for this study are similar to those reported in a previously published analysis of Medicare beneficiaries with cancer [Citation14].

Treatment patterns

Treatment pattern outcomes were measured from initial DLBCL diagnosis until end of study period (i.e., 31 December 2019), death, or censoring. We report the number of patients receiving first-line (1L+), second-line (2L+), third-line (3L+) and fourth-line (4L+) therapy (see Supplementary File 3 for lines of treatment algorithm). Time from initial diagnosis to initiation of each type of treatment was reported. This was defined as the number of days from the index date (i.e., date of first DLBCL diagnosis) to initiation of each type of treatment (among those receiving each type of treatment). We also reported both duration of lines of treatment and time between treatments. Duration of a line of treatment was defined as the number of days from the initiation of a line of treatment to the earliest date of discontinuation (defined as the start of a treatment-free interval of >60 days) or switch to a new line of treatment or until patient died or entered hospice (among those receiving each line of treatment). Time between treatments was a measure of the number of days between the end of a patient’s line of treatment to the initiation of a subsequent line of treatment. For self-administered DLBCL agents identified from the prescription claims data, this was defined as the date the last treatment was filled plus the days’ supply for that therapy. For the physician-administered anticancer agents (e.g., infusions) identified from the medical claims data, this was defined as the date the last treatment was administered plus a ‘presumed’ days’ supply based on the FDA label. The specific treatment a patient is receiving for DLBCL within each line of treatment was reported. In order to obtain mutually exclusive treatment groups and avoid double-counting of patients, a hierarchy was created in the classification of treatment regimens (Supplementary File 4). Finally, we report the number of patients receiving hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (see Supplementary File 5 for codes).

Overall survival

Patients were followed until end of the observation period to measure overall survival from the date of initiation of DLBCL treatment within each line of treatment.

Annual healthcare resource utilization & costs

All-cause and DLBCL-related healthcare resource utilization and costs during the 12 months after initiation of the specific line of treatment were examined. The rationale behind using a 12-month period for assessing HRU and costs is that most payers typically use annual budgets and hence annual numbers will be of greatest interest from a policy/payer perspective. By reporting annual costs, all patients contribute the same amount of time to the average (patients who die contribute US$0 for the months they are dead). This is in contrast to alternative measures such as per-patient-per-month (PPPM) wherein variable follow-up for each patient can result in a weighted average that may be an inaccurate representation and have little relevance to what the true costs may be within 12 months of treatment initiation. All-cause medical service use (hospitalization, skilled nursing facility stays, hospice care, home health visits, physician visits) was identified based on all medical claims, regardless of diagnosis. DLBCL-related medical service use was identified based on medical claims with a diagnosis of DLBCL in any position. Annual costs represent the total paid amount (payer and patient) on all medical and prescription claims for individual patients, then averaged across patients within each group. All-cause healthcare costs included measures of total costs, medical costs (further broken down into inpatient, skilled nursing facility, outpatient, hospice, home health and carrier costs) and prescription costs, regardless of the diagnosis or indication of use. DLBCL-related costs included measures of DLBCL-related total costs, medical costs and prescription costs. DLBCL-related medical costs were identified based on medical claims with a diagnosis of DLBCL in any position. For DLBCL-related prescription costs, we reported costs separately for the DLBCL treatment prescriptions (Supplementary File 2) captured in the prescription drug event (PDE) files (i.e., DLBCL-related Part D drug costs) and the DLBCL infusion/injectable treatments administered by or under supervision of a physician and captured in the outpatient hospital or carrier claim files (i.e., DLBCL-related Part B drug costs). We avoided double counting by excluding the DLBCL-related Part B drug costs from the reporting for the DLBCL related outpatient hospital and carrier claims costs. All-cause and DLBCL-related healthcare costs were inflated to 2020 US dollars using the medical care component of the 2020 US Consumer Price Index.

Analysis

Sample characteristics were described by line of treatment. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics included age, gender, race/ethnicity, low-income subsidy status, region, metropolitan status, National Cancer Institute (NCI)-adjusted Charlson comorbidity score, all-cause hospitalization in 12-month pre-index period, all-cause total healthcare costs in 12-month pre-index period and year of index date. Time to treatment initiation, duration of treatment, time between treatments, rates of healthcare resource utilization and healthcare costs were assessed descriptively. Overall survival was assessed using Kaplan–Meier estimators. All analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide Version 9.4 [Citation15]. This study was deemed exempt from review by Pearl IRB.

Results

We identified 11,880 Medicare beneficiaries newly diagnosed with DLBCL and receiving treatment in the frontline setting (see Supplementary File 6 for sample attrition table). Over a median follow-up of 2.1 years from initial DLBCL diagnosis among these patients, we found that 17.8% received 2L+ therapy (i.e., at least 2L therapy; some 2L patients also received 3L), 3.9% received 3L+ therapy and 0.9% received 4L+ therapy. Very few patients (n = 368) received a stem cell transplant during our study period, representing 3.1% of the overall sample and 17.4% of the 2L+ patients. The vast majority (>94%) received an autologous SCT and the remainder received allogenic SCT.

Patient sociodemographic and clinical characteristics by line of treatment are presented in . The median (interquartile range; IQR) age of 1L+ patients was 76.0 (71.0, 81.0) years; nearly one in three front line patients (31.6%) were ≥80 years old. Half (50.9%) of the 1L+ patients were male and the majority (90.0%) were White. Over a third of the 1L+ patients (36.1%) resided in the South and over three-quarters (79.3%) came from an urban area. Patients receiving a low-income subsidy constituted 13.8% of the patients receiving 1L+ therapy. Over one in four patients (29.3%) who received 1L+ therapy had evidence of a pre-index all-cause hospitalization in the 12-months before DLBCL diagnosis. Relapsed/refractory patients (i.e., all patients with evidence of 2L+ therapy) had a median (IQR) age of 75.0 (71.0, 80.0) years. The median (IQR) age was 75.0 (71.0, 80.0) years for 3L+ patients and 74.0 (70.0, 78.0) years for 4L+ patients, respectively. Over one in four patients (29.5%) receiving 2L+ therapy was ≥80 years old. Relapsed/refractory patients did not differ from frontline patients in other sociodemographic characteristics.

Table 1. Characteristics of treated elderly Medicare beneficiaries with newly diagnosed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma between 1 October 2015 and 31 December 2018 by line of treatment received.

Treatment patterns are presented in . Median (IQR) time to treatment initiation from diagnosis was 1.1 (0.7, 1.6) months. The majority (69.8%) of frontline patients initiated a CHOP-based regimen, most commonly R-CHOP (61.2%; Supplementary File 7); 8.9% of patients received rituximab monotherapy in the 1L setting. In the relapsed/refractory setting, the most common regimens were bendamustine-based regimens (20.3% [2L+], 20.8% [3L+], 13.6% [4L+]), gemcitabine-based regimens (18.2% [2L+], 20.2% [3L+], 19.1% [4L+]) and CHOP-based regimens (21.1% [2L+], 7.3% [3L+], <10% [4L+]). The median time between treatments from the end of the previous line of treatment to the beginning of the subsequent line of treatment ranged from about 2 to 7 weeks (51.0 days from 1L to 2L, 35.5 days from 2L to 3L, and 12.5 days from 3L to 4L). Other less frequently used treatments in 1L+ setting included CVP-based regimens (7.1%) and bendamustine-based regimens (6.2%). Other regimens (largely consisting of single agents or partial regimens) were also increasingly used in later lines (23.2% [2L+], >33.0% [3L+], 46.4% [4L+]).

Table 2. Treatment patterns among Medicare beneficiaries with diagnosed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by line of treatment.

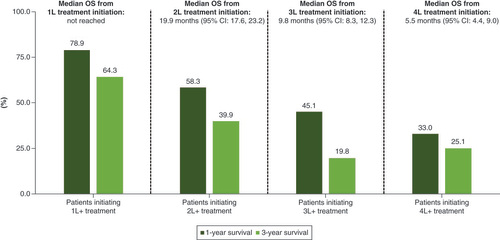

Median overall survival and the 1-year and 3-year survival rate is presented in . Median overall survival (OS) from 1L treatment initiation was not reached. Median OS was 19.9 , 9.8 and 5.5 months from the initiation of 2L, 3L and 4L treatment, respectively. The 1-year and 3-year OS rate was 78.9 and 64.3% from 1L treatment initiation, 58.3 and 39.9% from 2L treatment initiation, and 45.1 and 19.8% from 3L treatment initiation, respectively.

OS: Overall survival.

All-cause and DLBCL-related healthcare resource utilization in the 12 months after initiation of each specific line of treatment are presented in . HRU was substantial across all lines of therapy in the 12 months after initiating treatment. Over half of patients (57%) had a hospitalization due to any cause; most hospitalizations were DLBCL-related (71% of all hospitalizations). Hospice use increased in each line of therapy (13% [1L+], 32% [2L+], 44% [3L+], 59% [4L+]).

Table 3. Healthcare resource utilization among treated Medicare beneficiaries with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the 12-months after initiation of the specific line of treatment.

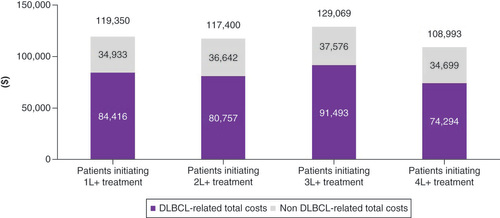

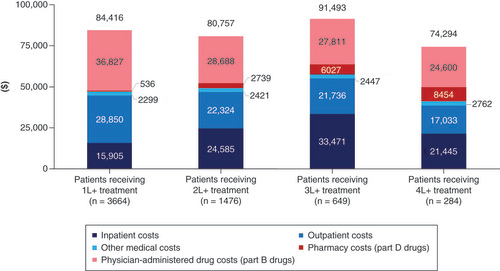

All-cause and DLBCL-related healthcare costs utilization in the 12 months after initiation of each specific line of treatment are presented in & , respectively. Across all lines of therapy, around 70% of all-cause costs could be attributed to DLBCL. DLBCL-related total healthcare costs in the 12 months after initiation of treatment were US$84,416 (1L+), $80,757 (2L+), $91,493 (3L+), $74,294 (4L+). Excluding patients who died within 12-months of treatment initiation, DLBCL-related total costs were higher for later lines of treatment (US$84,958 (1L+), $80,761 [2L+], $118,278 [3L+], $124,134 [4L+], Supplementary File 8). Less than half of DLBCL-related total costs were attributable to DLBCL-related pharmacy (Part D) and physician-administered (Part B) prescription drugs (US$37,362 [1L+], $31,427 [2L+], $33,838 [3L+], $33,054 [4L+]).

Discussion

This descriptive study of a national sample of Medicare beneficiaries provides important insights into real world treatment patterns, healthcare resource utilization, costs and survival among older adults being treated for DLBCL in the front line and relapse/refractory setting. In the front-line setting, we found that over two-thirds of our elderly sample received a CHOP-based regimen (most commonly R-CHOP), consistent with current clinical guidelines and prior work [Citation12,Citation13,Citation16–18]. However, it does suggest that nearly one in three elderly Medicare patients are not receiving the current standard of care treatment in the frontline setting. This may be reflective of previously reported difficulties faced by the elderly (especially the unfit or frail) in real-world clinical practice, who are unable to receive cytotoxic chemotherapy even with attenuated regimens [Citation9,Citation10,Citation19]. In the relapsed/refractory setting, we observed increased use of bendamustine-based regimens and gemcitabine-based regimens during our study period extending from 2015 to 2019. We also observed high use of other regimens in later lines of treatment with one-fifth of 2L+ patients, a third of 3L+ patients, and half of 4L+ patients receiving single agents or partial regimens. With newer treatments being approved for DLBCL and more recent therapies (such as CAR-Ts, monoclonal antibodies and ADCs) being moved to earlier lines of treatment, future studies must evaluate whether these other regimens are being replaced by newer treatment options and resulting in improved clinical outcomes.

Despite its curative potential, very few patients in our sample had evidence of stem cell transplant (3.1% of the overall sample and 17.4% of the 2L+ patients). Low transplant use in the Medicare population was seen in a prior study by Shaw et al. [Citation7], which found that only 1.3% of patients had evidence of stem cell transplant. Given the higher risk of complications of SCT in older adults (such as cardiovascular toxicity or gastrointestinal complication), our findings are perhaps not surprising. Evidence also suggests that even with SCT, older patients with relapsed/refractory DLBCL still experience higher risk of second relapse and higher mortality, with long-term survival rates of less than 20% [Citation19–21]. It should be noted that in the relapsed/refractory setting the time between treatments was small (less than 2 months between the end of 1L and beginning of 2L and ~1 month from the end of 2L to beginning of 3L). This suggests that these patients are quickly starting another therapy after failure on a given regimen, with survival rates decreasing in these later lines. Taken together, our findings underscore the need for alternative efficacious and well-tolerated therapeutic options for the elderly population, particularly in the relapsed/refractory setting.

Healthcare resource use was high in both the frontline and relapsed refractory population. Of note was the high rate of hospitalization observed in both groups: over half of frontline patients had evidence of a hospitalization during the follow-up period; the rate was even higher in the relapsed/refractory population, with nearly two-thirds of patients having evidence of a hospitalization. In both cases, the majority of hospitalizations were DLBCL-related. While few patients in the frontline setting entered hospice during the follow-up period, nearly a third of patients in the relapsed/refractory setting entered hospice. These rates increased with subsequent lines of therapy: nearly half of 3L+ patients and nearly two-thirds of 4L+ patients entered hospice during the follow-up period. Total healthcare costs over 12-months from treatment initiation were substantial across all lines of therapy; for instance, 12-month all-cause costs in the 1L+ setting were US$119,350, which represents a more than fivefold increase in all-cause costs compared with the 12-months prior to DLBCL diagnosis. The costs were largely attributable to DLBCL (~70% of total costs across all lines) and 56 to 63% of the DLBCL-related costs were medical costs (primarily inpatient).

At a median follow-up of 2.1 years from diagnosis, median OS was not reached in the front-line setting. However, the 1-year and 3-year OS rate was 81.7 and 65.8% from initial DLBCL diagnosis and 78.9 and 64.3% from 1L treatment initiation, respectively. Notably, a previous study that examined DLBCL patients using 2004–2011 SEER-Medicare data found virtually identical 1-year and 3-year survival rates (~80 and 64%, respectively) in the frontline setting as those reported in our study despite the fact that our study uses much more recent data (2015–2019) [Citation22]. This suggests that any overall survival improvements in the front-line setting that have been achieved from existing regimens (e.g., R-CHOP) were already realized prior to 2014 and thus further improving survival may require the introduction of newer therapies or improved patient selection and delivery for existing therapies. In addition, we found poor overall survival among elderly patients with DLBCL in the relapsed/refractory setting. In particular, median overall survival was <10 months from 3L treatment initiation and <6 months from 4L initiation, respectively.

Our study has several limitations. First, claims data lacks clinical information (e.g., lymphoma stage, laboratory values) that would allow for a more robust analysis. However, this limitation is offset by the advantage of having 100% Medicare claims that permits efficient generalizable and timely population-level analyses with comprehensive information on healthcare utilization and costs incurred by the patients regardless of setting. Third, our definition of relapsed/refractory DLBCL and lines of treatment is imperfect given that no specific diagnostic code exists to identify relapsed/refractory patients. However, our proxy measure (i.e., classifying patients as relapsed/refractory if they have evidence of subsequent anticancer therapy) and algorithm to identify lines of treatment has been used in prior studies [Citation6,Citation7,Citation12,Citation13]. Fourth, our study is generalizable only to the fee-for-service Medicare population rather than the Medicare Advantage population since claims/encounter data are not available from CMS for the latter. However, during our study period, approximately 70% of the US Medicare population was covered under the fee-for-service Medicare program [Citation23]. Given that the median age at diagnosis for DLBCL is approximately 70 years, our sample also represents the elderly population with DLBCL (this group is historically understudied in the literature). Fifth, the proportion of patients treated might be an underestimate because treatments used during hospitalization (such as chemotherapy) are not fully captured in claims data. Although revenue or diagnosis codes may indicate the administration of chemotherapy for some patients, these codes are not specific and thus do not identify the chemotherapy drug used. Sixth, while it is possible that some patients may have received CAR-T therapy in the latter part of our study period, we were unable to observe utilization of CAR-Ts (and other more recent therapies) given our data period ended in 2019 and thus specific codes for CAR-Ts and later therapies were not yet available. Finally, loss to follow-up was possible if patients transitioned over post-index follow-up from Medicare fee-for-service to Medicare Advantage plans (since data are unavailable for these patients).

Conclusion

This real-world study provides a baseline for treatment patterns and outcomes in a national sample of elderly US Medicare beneficiaries diagnosed with DLBCL in the period immediately prior to the approval of newer novel agents (for which data is still accumulating). Our study finds that a considerable proportion of patients were not receiving standard-of-care treatments, possibly due to tolerability concerns in the elderly. In addition, we found high rates of hospitalization and hospice use, substantial healthcare costs and poor overall survival, especially in those requiring treatment beyond the first line setting. Our study results when taken together are suggestive of a large current unmet need for more efficacious and well-tolerated treatment modalities in the elderly population of DLBCL patients in both the front-line and relapse/refractory settings.

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is an aggressive type of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma that becomes more common as people grow older.

While standard of care R-CHOP therapy (frontline) and stem-cell transplant (relapsed/refractory) have improved survival for many patients, difficulties remain in optimizing these therapies for certain populations, such as the elderly.

Given ongoing development of novel therapies for DLBCL, it is important to understand real-world treatment patterns and economic burden in individuals diagnosed with DLBCL, particularly in the elderly population.

This retrospective cohort study using 2014–2019 Medicare claims data identified 11,880 Medicare beneficiaries diagnosed with DLBCL in the frontline setting; the majority (70.1%) of these patients were treated with R-CHOP (61.2%) or rituximab monotherapy (8.9%).

Over a median follow-up of 2.1 years, 17.8% went on to receive at least second-line treatment; however, very few patients (3.1%) received a stem cell transplant.

Overall survival was lower among later lines of treatment (median overall survival from initiation of 1L: not reached; 2L: 19.9 months; 3L: 9.8 months; 4L: 5.5 months).

Healthcare resource utilization and costs were substantial in the 12-months after initiation of a given line of treatment.

The findings from this national sample of elderly Medicare beneficiaries suggests a large current unmet need for more efficacious and well-tolerated treatment modalities in the elderly population of DLBCL patients in both the front-line and relapse/refractory settings.

Supplemental Text 1

Download MS Word (124.9 KB)Supplementary data

To view the supplementary data that accompany this paper please visit the journal website at: www.tandfonline.com/doi/suppl/10.2217/fon-2023-0191

Financial disclosure

This study was funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA. The sponsor was involved in the interpretation of results and drafting of the manuscript. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Competing interests disclosure

M Garg, M Raut and KE Ryland are employees of Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA. J Puckett and S Kamal-Bahl are employees of COVIA Health Solutions, a consulting form with clients in the biotech/pharmaceutical industry. SF Huntington: consultancy for Janssen, Pharmacyclics, AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Flatiron Health Inc., Novartis, SeaGen, Genetech, Merck, TG Therapeutics, ADC Therapeutics, Epizyme, Servier, Arvinas, and Thyme Inc.; research funding from Celgene, DTRM Biopharm, and TG Therapeutics; honoraria form Pharmacyclics and AstraZeneca, Bayer; JA Doshi: consultancy for AbbVie, Acadia, Janssen, Merck, Otsuka, and Takeda; research funding from Merck and Spark Therapeutics. The authors have no other competing interests or relevant affiliations with any organization or entity with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Writing disclosure

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

- Thandra KC , BarsoukA, SaginalaK, PadalaSA, BarsoukA, RawlaP. Epidemiology of Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. Med. Sci.9(1), 5 (2021).

- Coiffier B , ThieblemontC, VanDen Neste Eet al. Long-term outcome of patients in the LNH-98.5 trial, the first randomized study comparing rituximab-CHOP to standard CHOP chemotherapy in DLBCL patients: a study by the Groupe d’Etudes des Lymphomes de l’Adulte. Blood116(12), 2040–2045 (2010).

- Friedberg JW . Relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program.2011, 498–505 (2011).

- Coiffier B , SarkozyC. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: r-CHOP failure-what to do?Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program.2016(1), 366–378 (2016).

- Danese MD , GriffithsRI, GleesonMLet al. Second-line therapy in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL): treatment patterns and outcomes in older patients receiving outpatient chemotherapy. Leuk. Lymphoma58(5), 1094–1104 (2017).

- Huntington S , KeshishianA, McGuireM, XieL, BaserO. Costs of relapsed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma among Medicare patients. Leuk. Lymphoma59(12), 2880–2887 (2018).

- Shaw J , HarveyC, RichardsC, KimC. Temporal trends in treatment and survival of older adult diffuse large B-Cell lymphoma patients in the SEER-Medicare linked database. Leuk. Lymphoma60(13), 3235–3243 (2019).

- Smith A , HowellD, PatmoreR, JackA, RomanE. Incidence of haematological malignancy by sub-type: a report from the Haematological Malignancy Research Network. Br. J. Cancer105(11), 1684–1692 (2011).

- Delarue R , TillyH, MounierNet al. Dose-dense rituximab-CHOP compared with standard rituximab-CHOP in elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (the LNH03-6B study): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol.14(6), 525–533 (2013).

- Wieringa A , BoslooperK, HoogendoornMet al. Comorbidity is an independent prognostic factor in patients with advanced-stage diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP: a population-based cohort study. Br. J. Haematol.165(4), 489–496 (2014).

- Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse . Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (2023). www2.ccwdata.org

- Morrison VA , BellJA, HamiltonLet al. Economic burden of patients with diffuse large B-cell and follicular lymphoma treated in the USA. Future Oncol. Lond. Engl.14(25), 2627–2642 (2018).

- Yang X , LalibertéF, GermainGet al. Real-World Characteristics, Treatment Patterns, Health Care Resource Use, and Costs of Patients with Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma in the US The Oncologist. 26(5), e817–e826 (2021).

- Squires P , PuckettJ, RylandKEet al. Assessing unmet need among elderly Medicare Beneficiaries with Mantle cell lymphoma: an analysis of treatment patterns, survival, healthcare resource utilization, and costs. Leuk. Lymphoma64(11), 1752–1770 (2023).

- SAS Institute . SAS: Analytics, Artificial Intelligence and Data Management | SAS. www.sas.com/en_us/home.html

- Purdum A , TieuR, ReddySR, BroderMS. Direct Costs Associated with Relapsed Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma Therapies. The Oncologist.24(9), 1229–1236 (2019).

- Ren J , AscheCV, ShouY, GalaznikA. Economic burden and treatment patterns for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and follicular lymphoma in the USA. J. Comp. Eff. Res.8(6), 393–402 (2019).

- Tkacz J , GarciaJ, GitlinMet al. The economic burden to payers of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma during the treatment period by line of therapy. Leuk. Lymphoma61(7), 1601–1609 (2020).

- Di M , HuntingtonSF, OlszewskiAJ. Challenges and Opportunities in the Management of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma in Older Patients. The Oncologist.26(2), 120–132 (2021).

- Jantunen E , CanalsC, RambaldiAet al. Autologous stem cell transplantation in elderly patients (> or = 60 years) with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: an analysis based on data in the European Blood and Marrow Transplantation registry. Haematologica93(12), 1837–1842 (2008).

- Andorsky DJ , CohenM, NaeimA, Pinter-BrownL. Outcomes of auto-SCT for lymphoma in subjects aged 70 years and over. Bone Marrow Transplant.46(9), 1219–1225 (2011).

- Huntington SF , HoagJR, ZhuWet al. Oncologist volume and outcomes in older adults diagnosed with diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Cancer124(21), 4211–4220 (2018).

- Freed M . Seven in Ten Medicare Beneficiaries Did Not Compare Plans During Past Open Enrollment Period.KFF (2021). www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/seven-in-ten-medicare-beneficiaries-did-not-compare-plans-during-past-open-enrollment-period/