Abstract

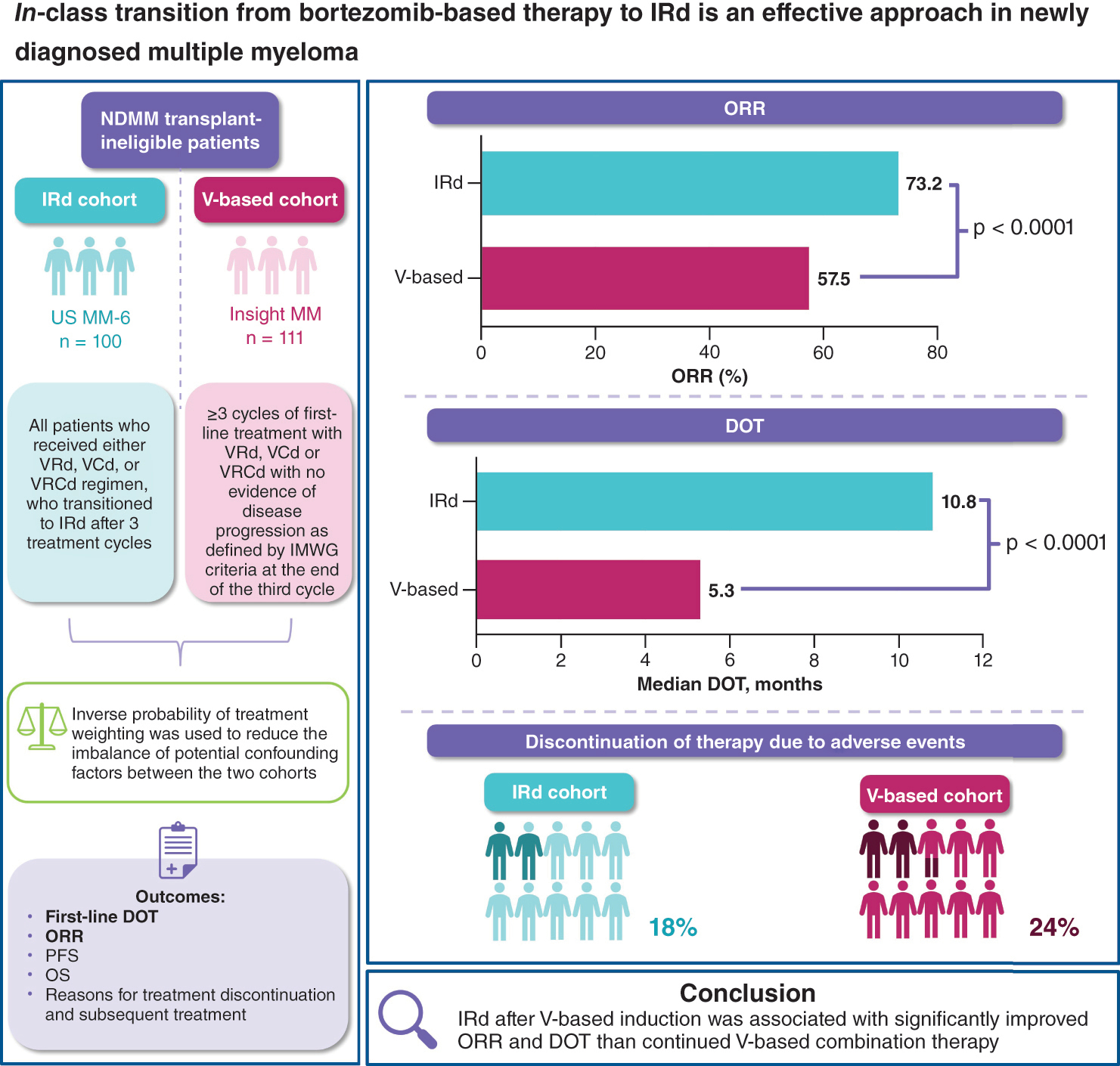

Aim: To compare the effectiveness of in-class transition to all-oral ixazomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone (IRd) following parenteral bortezomib (V)-based induction versus continued V-based therapy in US oncology clinics. Patients & methods: Non-transplant eligible patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MM) receiving in-class transition to IRd (N = 100; US MM-6), or V-based therapy (N = 111; INSIGHT MM). Results: Following inverse probability of treatment weighting, overall response rate was 73.2% with IRd versus 57.5% with V-based therapy (p < 0.0001). Median duration of treatment was 10.8 versus 5.3 months (p < 0.0001). Overall, 18/24% of patients discontinued IRd/V-based therapy due to adverse events. Conclusion: IRd after V-based induction was associated with significantly improved overall response rate and duration of treatment than continued V-based combination therapy.

Clinical Trial Registration: US MM-6: NCT03173092; INSIGHT MM: NCT02761187 (ClinicalTrials.gov)

Graphical abstract

Long-term proteasome inhibitor (PI)-based treatment can improve outcomes for patients with multiple myeloma (MM) [Citation1–3]. However, prolonged parenteral PI therapy, for example with bortezomib (V), can be challenging to achieve in routine clinical practice, and outcomes for patients are often poorer in this setting compared with those observed in randomized clinical trials (RCT) [Citation4]. This discrepancy could be due in part to the fact that up to 72% of patients with relapsed/refractory MM (RRMM) and up to 40% of patients with newly diagnosed MM (NDMM) in routine clinical practice would not meet the eligibility criteria for RCTs [Citation5,Citation6]. In the CONNECT MM Registry, a large, prospective observational cohort study of patients with NDMM in the USA, RCT-ineligible patients had a lower 3-year survival rate than RCT-eligible patients (63 vs 70%) [Citation6]. Studies conducted in community oncology centers/practices with less stringent eligibility criteria may permit inclusion of a more diverse patient population and better inform on the effectiveness of therapies used in this setting [Citation5].

Various physical, geographical and/or socioeconomic barriers to prolonged therapy with parenteral PIs are encountered in community practice, and include difficulty traveling to treatment centers, comorbidities, toxicities [Citation4] and patient preference for treatment outside of a clinic. Self-administered oral therapies could overcome some of these barriers, and indeed, median progression-free survival (PFS) appears more closely aligned between clinical trials and reports from routine clinical practice with all-oral compared with injectable regimens [Citation4]. Transition from injectable to all-oral regimens may prolong treatment, potentially leading to improved patient outcomes.

The objective of this analysis was to examine the effectiveness of in-class transition (iCT) from parenteral V-based induction to all-oral ixazomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone (IRd) therapy versus remaining on V-based combination therapy until progression in patients with NDMM in oncology practices in the USA. Data for IRd-treated patients were obtained from the ongoing community-based, single-arm, US MM-6 study (NCT03173092), which is assessing iCT from V-based induction to all-oral IRd in transplant-ineligible NDMM patients treated in routine clinical practice, with the objective of increasing the duration of PI-based treatment while maintaining quality of life [Citation7]. A comparator cohort of patients who continued to receive V-based therapy was obtained from the INSIGHT MM study (NCT02761187), the largest global, prospective, observational study of MM patients (n = 4253) [Citation8].

Patients & methods

Patients & study designs

The current study was a secondary pooled analysis of data collected prospectively from two studies (MM-6 and INSIGHT MM). The study designs for MM-6 and INSIGHT MM have been described previously [Citation7,Citation8]. In brief, MM-6 recruited adults with NDMM from 22 US community sites between October 2017 and May 2021. Patients were transplant ineligible or transplant-delayed for ≥24 months, and had received first-line V-based induction per National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines with no evidence of progressive disease (PD) after 3 treatment cycles [Citation7]. Additionally, patients had baseline Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) or overall performance status of 0, 1 or 2, and no grade ≥2 peripheral neuropathy (PN) or grade 1 PN with pain, at enrollment. Patients were enrolled within 14 days of completing their third V-based induction cycle and received IRd (ixazomib 4 mg on days 1, 8 and 15; lenalidomide 25 mg on days 1–21 and dexamethasone 40 mg [20 mg for patients aged >75 years] on days 1, 8, 15 and 22) in 28-day cycles for a maximum of 39 cycles or until progression or unacceptable toxicity, in accordance with the US FDA-approved label. Assessments were performed each 28-day treatment cycle at the investigator’s discretion. While enrollment in MM-6 is now closed, follow-up is ongoing with patients being followed for ≥2 years. The IRd cohort in the current analysis included all patients who received either VRd, V-cyclophosphamide-d (VCd), or VRCd as their induction regimen, who transitioned to IRd after 3 treatment cycles of the V-based induction therapy (Supplementary Figure 1 [Citation9,Citation10]). The MM-6 interim data cutoff date was 4 May 2021.

The recently completed INSIGHT MM study enrolled both NDMM and RRMM patients ≥18 years of age from sites in Asia, Europe, Latin America and the USA between July 2016 and July 2021 [Citation8]. Patients with NDMM had to enroll within 3 months of treatment initiation. Patients were treated according to standard of care at their site of enrollment. The majority of assessments were performed quarterly; ECOG PS was measured at baseline and then on a yearly basis. Patients were followed up for a minimum of 2 years. The INSIGHT MM data cut-off date was 28 July 2020. To match the characteristics of the MM-6 IRd cohort as closely as possible, eligibility criteria for inclusion of patients from INSIGHT MM in the V-based cohort of the current pooled analysis were as follows: ≥3 cycles of first-line treatment with VRd, VCd or VRCd with no evidence of disease progression as defined by International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) criteria at the end of the third cycle; ECOG PS of ≤2; no stem cell transplant at baseline or during first-line therapy; classified as frail (based on the Simplified Frailty Score estimated using age, Charlson Comorbidity Index [CCI] and ECOG PS [Citation3]) and therefore ineligible for stem cell transplant; treated at oncology clinics in the US (mostly community oncology clinics, with some patients treated at academic centers) and International Staging System (ISS) information available. In INSIGHT MM, CCI was collected using patient history from the year prior to study enrollment whereas for MM-6, this information was derived from the patient medical history from the electronic case report form.

Outcomes

Baseline study measures were assessed using data collected from the baseline visit at the time of study enrollment, including age, sex, race, facility type (community or academic); MM disease characteristics, comorbidities, V-based induction regimen type and simplified frailty score (0–1 non-frail; ≥2 frail).

Unless specified differently, study outcomes in this analysis were assessed from the index date (Supplementary Figure 1 [Citation9,Citation10]), defined as the date of initiating V-based (VRd or VCd) induction therapy until the end of follow-up (last contact date prior to study discontinuation or date of death, whichever occurred first). Outcomes included first-line duration of treatment (DOT), overall response rate (ORR), PFS, overall survival (OS), reasons for treatment discontinuation, subsequent treatment (stem cell transplant after first-line therapy and PI in the next line of therapy) and follow-up duration, which was the length of time in months from the index date until date of any-cause death or end of follow-up. DOT was defined as the time from the index date to the date of the last administration of any of the three study drugs in the IRd regimen or first-line V-based regimen (event), death (due to any cause, event), or end of follow-up (censored). ORR was defined as the proportion of patients with partial response (PR), very good partial response (VGPR), complete response (CR) and stringent complete response (sCR) during treatment and prior to disease progression. PFS was defined as the time from the index date until the date of disease progression (event), date of death (for any cause, event), or end of follow-up (censored). OS was defined as the length of time from the index date until the date of death (for any cause, event), or end of follow-up (censored).

Statistical analyses

Inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) was used to reduce the imbalance of potential confounding factors between the two treatment cohorts. This IPTW method calculates a weight for each patient based on the inverse probability of receiving their actual treatment. The application of these weights either increases or decreases the contribution of each patient to the analyses. For example, patients receiving IRd with a lower probability of exposure to this treatment receive higher weights. This method creates a pseudopopulation where the resulting sample sizes may be slightly different from the size of the original, unweighted cohorts. Specifically, propensity scores representing probability of transitioning to IRd (p(x)) were estimated by regressing treatment assignment against pre-treatment factors using a multivariable logistic/probit regression model. The weight of each individual patient was equal to the inverse of their propensity score (1/p(x)) for those transitioning to IRd and 1/(1-p(x)) for those remaining on V-based therapy, where p(x) was the probability of receiving IRd given a set of baseline covariates. The propensity score models included the following baseline characteristics: age category (<55, 55–64, 65–74, and ≥75 years), sex, BMI category (<18.5, 18.5 to <25, 25 to <30 and ≥30 kg/m2), ECOG PS (0, 1, 2, 3 and 4), ISS Stage (I, II and III), induction therapy type (VRd, VCd and VRCd) and CCI.

Analyses were performed for outcome measures weighted using the IPTW approach described above, applied to the analysis populations. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate DOT, PFS, OS and associated 95% CIs; the log-rank test was used to compare distribution of time-to-event outcomes. The Clopper-Pearson method was applied to estimate 95% CIs for ORR. Statistical significance was evaluated at alpha = 0.05. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 or higher statistical software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patients

Of 101 patients enrolled in US MM-6 at the time of analysis, 100 patients were included in the IRd cohort; one patient was excluded as they received Vd (not triplet/combination therapy) as the induction regimen. Of 2339 patients with NDMM in INSIGHT MM at the time of analysis, 111 were eligible for inclusion in the V-based cohort (Supplementary Figure 2 [Citation9,Citation10]). The IPTW method was then applied to each of the two treatment cohorts, to reduce the imbalance of potential confounders in the comparative effectiveness analyses, resulting in slightly different sample sizes from the original, unweighted cohorts. After IPTW weighting, 113 patients from US MM-6 and 102 patients from INSIGHT MM contributed to the analyses.

The IPTW-weighted IRd versus V-based cohorts were well-balanced: the median age was 75.0 versus 74.8 years, 57 versus 51% of patients were male, 37 versus 29% had an ECOG PS of 2, and 49 versus 41% had ISS Stage III at initial diagnosis ( [Citation9,Citation10]). In total, 79, 18 and 3% of patients in the IRd cohort received VRd, VCd, and VRCd, respectively, as their initial induction therapy. Corresponding percentages for the V-based cohort were 77, 20 and 3%. All patients from the IRd cohort and 92% from the V-based cohort were treated at community centers. CCI scores of 0/1/2/3+ for patients in the IRd cohort were 31/15/18/36% and in the V-based cohort were 38/13/20/29%. Statistically significant differences between the IRd and V-based cohorts were identified in the median follow-up period (20.3 vs 15.8 months) and included race (see [Citation9,Citation10]) and facility type (with 0 vs 9% of patients treated at academic centers). Patient baseline and disease characteristics prior to IPTW-weighting are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Table 1. Patient baseline and disease characteristics after inverse probability of treatment weighting.

Effectiveness

Adjusted ORRs in the IPTW-weighted IRd versus V-based cohorts were 73.2% (95% CI: 65.0–81.3) versus 57.5% (95% CI: 47.9–67.1; p < 0.0001; [Citation9,Citation10]). CR rates were 25.7 and 20.5%, and VGPR rates were 24.3 and 20.2%, respectively. After the median follow-up of 20.3 months in the IRd cohort and 15.8 months in the V-based cohort, median DOT was 10.8 months (95% CI: 6.5–24.4) versus 5.3 months (95% CI: 4.3–7.0, p < 0.0001; [Citation9,Citation10] & ). In the V-based cohort, the duration of initial PI treatment was 5.1 months (95% CI: 4.3–6.7), and in the IRd cohort, durations of initial PI, lenalidomide (R), and dexamethasone (d) treatment were 10.5 months (95% CI: 3.9–28.1), 7.4 months (95% CI: 3.0–22.5) and 10.5 months (95% CI: 4.4–29.2), respectively (Supplementary Table 2).

*Defined as the proportion of patients with partial response, very good partial response, complete response and stringent complete response during initial treatment regimen and prior to disease progression.

IPTW: Inverse probability of treatment weighting; IRd: Ixazomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone; ORR: Overall response rate; V: Bortezomib.

Reprinted from Poster P947 presented at the 27th Congress of the European Hematology Association (EHA) 2022, Copyright © 2022 The Author(s) [Citation9].

Abstract Book for the 27th Congress of the European Hematology Association. Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. on behalf of the European Hematology Association [Citation10].

![Figure 1. Adjusted ORR* in the IRd and V-based inverse probability of treatment weighted cohorts.*Defined as the proportion of patients with partial response, very good partial response, complete response and stringent complete response during initial treatment regimen and prior to disease progression.IPTW: Inverse probability of treatment weighting; IRd: Ixazomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone; ORR: Overall response rate; V: Bortezomib.Reprinted from Poster P947 presented at the 27th Congress of the European Hematology Association (EHA) 2022, Copyright © 2022 The Author(s) [Citation9].Abstract Book for the 27th Congress of the European Hematology Association. Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. on behalf of the European Hematology Association [Citation10].](/cms/asset/57a2bf07-028d-4129-8f81-cab2e3f5a0c7/ifon_a_12366817_f0001.jpg)

*Time from the index date (date that patients began V-based therapy) to the date of the last administration of any of the three study drugs in the IRd regimen or first-line V-based regimen for comparators (event), death (due to any cause, event), or end of follow-up (censored).

DOT: Duration of treatment; IPTW: Inverse probability of treatment weighting; IRd: Ixazomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone; V: Bortezomib.

Reprinted from Poster P947 presented at the 27th Congress of the European Hematology Association (EHA) 2022, Copyright © 2022 The Author(s) [Citation9].

Abstract Book for the 27th Congress of the European Hematology Association. Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. on behalf of the European Hematology Association [Citation10].

![Figure 2. Adjusted DOT regimen* in the IRd and V-based inverse probability of treatment weighted cohorts.*Time from the index date (date that patients began V-based therapy) to the date of the last administration of any of the three study drugs in the IRd regimen or first-line V-based regimen for comparators (event), death (due to any cause, event), or end of follow-up (censored).DOT: Duration of treatment; IPTW: Inverse probability of treatment weighting; IRd: Ixazomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone; V: Bortezomib.Reprinted from Poster P947 presented at the 27th Congress of the European Hematology Association (EHA) 2022, Copyright © 2022 The Author(s) [Citation9].Abstract Book for the 27th Congress of the European Hematology Association. Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. on behalf of the European Hematology Association [Citation10].](/cms/asset/7ca52aa3-f17f-4952-b00f-991157f82a72/ifon_a_12366817_f0002.jpg)

Table 2. Time-to-event outcomes after inverse probability of treatment weighting.

After a median follow-up period of 20.3 and 15.8 months in the IRd and V-based cohorts, respectively, median PFS and OS were not reached in either cohort, however some separation between cohorts began to emerge over time (A & B [Citation9,Citation10], & ). PFS rates in the IRd versus the V-based cohorts were 96.0 versus 95.3% at 6 months, 86.9 versus 87.5% at 12 months, 85.7 versus 80.1% at 18 months and 85.7 versus 76.5% at 24 months. Corresponding OS rates were 100 versus 98.0% at 6 months, 99.3 versus 96.6% at 12 months, 96.9 versus 90.4% at 18 months and 94.0 versus 84.9% at 24 months.

(A) Adjusted PFS; (B) Adjusted OS.

*IPTW-weighted cohorts.

IPTW: Inverse probability of treatment weighting; IRd: Ixazomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone; NE: Not estimable; PFS: Progression-free survival; OS: Overall survival; V: Bortezomib.

Reprinted from Poster P947 presented at the 27th Congress of the European Hematology Association (EHA) 2022, Copyright © 2022 The Author(s) [Citation9].

Abstract Book for the 27th Congress of the European Hematology Association. Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. on behalf of the European Hematology Association [Citation10].

![Figure 3. Adjusted outcomes in the IRd and V-based inverse probability of treatment weighted cohorts. (A) Adjusted PFS; (B) Adjusted OS.*IPTW-weighted cohorts.IPTW: Inverse probability of treatment weighting; IRd: Ixazomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone; NE: Not estimable; PFS: Progression-free survival; OS: Overall survival; V: Bortezomib.Reprinted from Poster P947 presented at the 27th Congress of the European Hematology Association (EHA) 2022, Copyright © 2022 The Author(s) [Citation9].Abstract Book for the 27th Congress of the European Hematology Association. Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. on behalf of the European Hematology Association [Citation10].](/cms/asset/a31a85ae-f940-4416-b45a-a7b259699607/ifon_a_12366817_f0003.jpg)

Treatment discontinuation & subsequent therapy

Reasons for treatment discontinuation were reported for 63 and 72% of IRd and V-based cohort patients, respectively. In the IRd cohort, 23% of patients discontinued treatment due to PD and 48% due to patient request. In the V-based cohort, 13, 13, 10 and 15% of patients discontinued V, R, cyclophosphamide, and d due to PD, and <1% discontinued due to patient request. In total, 18% of patients from the IRd cohort discontinued IRd, and 24% from the V-based cohort discontinued V, due to an adverse event (AE; [Citation9,Citation10]). Of all patients who discontinued due to an AE, the most common AEs leading to discontinuation were worsening PN, diarrhea and anorexia/fatigue in the IRd cohort, occurring in 22, 12 and 11% of patients. In the V-based cohort, the most common AEs leading to discontinuation of V were PN (45%) and skin rash (16%). Other reasons for discontinuation of treatment are shown in [Citation9,Citation10].

Table 3. Reasons for discontinuation of IRd and V in the V-based inverse probability of treatment weighted cohorts.

In the V-based cohort, 7.3% received a stem cell transplant after the first line of therapy, and 22% received a PI in the next line of therapy (Supplementary Table 3).

Discussion

In this analysis of patients with NDMM treated in oncology clinical settings in the USA, transition to IRd after 3 initial cycles of V-based induction was associated with significantly higher ORR and longer DOT compared with patients who continued to receive V-based combination therapy. Although no significant differences in median PFS or OS were observed between cohorts, numerical trends for 18- and 24-month PFS and OS favored IRd. iCT from V-based therapy to all-oral IRd therapy resulted in a numerically lower treatment discontinuation rate due to AEs compared with patients who continued to receive V-based combination therapy. These results suggest that iCT from V-based therapy to all-oral IRd may improve outcomes in patients treated at US oncology clinics. In addition to offering a viable treatment option, the ability to transition from a parenteral to an oral treatment regimen could prevent disruption to patients’ treatment course. All-oral IRd may be particularly beneficial to patients with restricted mobility (e.g., elderly patients), those who prefer to remain outside of a hospital/clinic setting for treatments, or younger patients with work commitments/family obligations [Citation13–15].

There were differences in collection of data on reasons for treatment discontinuation between the two studies, data were collected for each first-line agent in INSIGHT MM and for the overall IRd regimen in US MM-6. In addition, a considerable proportion of patients discontinuing V-based therapy in INSIGHT MM did not report a reason for discontinuation. The percentage of patients reporting discontinuation due to AEs differed between the two cohorts. Notably, PN was reported as the reason for discontinuation in 45% of patients who reported discontinuing due to AEs in the V-based cohort, compared with 22% (13% worsening PN, 5% peripheral sensory neuropathy, 4% bilateral sensory neuropathy) with IRd. Discontinuation rates due to gastrointestinal toxicity were low in both cohorts, although more common in the IRd cohort compared with the V-based cohort; this is consistent with the known safety profile of ixazomib [Citation16]. Overall, 48 and <1% of patients discontinued IRd and V-based therapy due to patient request, respectively. In addition to differences between studies in reporting discontinuation reasons, this could be partly due to the IRd cohort receiving treatment for twice as long as the V-based cohort (median 10.8 vs 5.3 months following 3 cycles of V-based induction). In the SWOG S0777 RCT, patients received fewer cycles of PI-based therapy (eight 21-day cycles of VRd induction followed by Rd maintenance) than in US MM-6, and 44% (n = 104) of patients did not complete VRd induction as planned [Citation17].

Due to strict eligibility criteria, generalizability of results from RCTs to patients in real-world settings can be limited. The US MM-6 and INSIGHT MM studies were designed to capture results reflective of the experiences of patients receiving treatment for MM in real-world clinical practice. A prior analysis revealed that almost 40% of the patients with NDMM enrolled in INSIGHT MM would have been ineligible for RCTs based on not meeting at least one of the 20 standard eligibility criteria [Citation18]. The results of this comparative effectiveness analysis may therefore better represent the results within diverse NDMM populations typically treated in clinical settings.

Study limitations

As expected with analyses of this nature, there are several limitations to note. The follow-up periods at the time of the data analysis were too short to robustly assess PFS and OS. Nevertheless, updated survival data from the fully accrued US MM-6-based cohort demonstrated promising overall 2-year PFS (71%) and OS (86%) rates, and improvement in ORR (from 62.1 to 80.0%) in patients who transitioned from V-based therapy to all-oral IRd after a median follow-up of 26.8 months. These data align with our current findings, further supporting the effectiveness of this treatment approach in community-based patients with NDMM [Citation19]. The lack of difference between the IRd and V-based cohorts during the first 2 years of therapy is reflective of the fact that these therapies are effective and few deaths or progression events were seen within the initial treatment period. Additionally, detection of disease progression in INSIGHT MM relied on the interpretation of clinical examinations and radiological imaging from patients’ medical records, which may have been interpreted relatively more subjectively compared with US MM-6. INSIGHT MM was an observational study where outcomes were assessed on a quarterly basis, whereas outcomes for the US MM-6 trial were assessed at each 28-day treatment cycle. This difference in timing of the assessments may have introduced bias, particularly for time-to-event analyses, as patients in the IRd cohort were being followed-up more frequently. In addition, there were differences in geography across the two studies (INSIGHT MM was a global study, whereas US MM-6 was restricted to the USA). To account for this, only INSIGHT MM patients residing in the USA were included in this analysis. This ensured more balanced cohorts, however, it also resulted in a reduced sample size for this analysis. Furthermore, not all patients included in this analysis were from a community oncology setting, with a small proportion of INSIGHT MM patients (9% after IPTW) recruited from academic centers. Moreover, due to lack of availability of baseline fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), cytogenetic-risk status was not considered during cohort selection. Therefore, the balance between high-risk and standard-risk cytogenetic abnormalities in each cohort was unknown and may have impacted efficacy outcomes. Lack of sequential FISH is common in the MM community as it requires serial bone marrow aspirates, which are inconvenient for, or unavailable to, some patients [Citation4]. In a comprehensive analysis of cytogenetic testing among patients with MM across the USA, the authors reported variability not only in the use of cytogenetic testing (i.e., conventional metaphase karyotyping and FISH) but also in how tests may be performed by laboratories, and concluded that the international myeloma community needs to devise a standardized methodology and interpretation guideline for cytogenetic analysis in patients with MM [Citation20]. Also lacking were reasons for the 34 patient requests in the IRd cohort (approximately 30% of the total cohort and 48% of those who discontinued IRd) to discontinue treatment. While this was higher than that (22.5%) reported in a recent retrospective analysis of 340 patients with MM who had received maintenance therapy (most commonly with bortezomib or lenalidomide) for <3 years post-ASCT [Citation21], it is important to note that collecting treatment discontinuation data is challenging when dependent on patient record entries. We acknowledge that non-collation of reasons for patient withdrawal is a limiting factor in our study and as such are currently updating the study database to enable more robust capture of these missing data. Finally, IPTW was based on observed covariates, and thus any confounding due to unobserved covariates (e.g., residual confounding) could not be accounted for. Based on the limitations of this analysis, future research should entail further evaluation of these findings, including in other MM patient population settings and using differing data sources.

Conclusion

In this real-world study of transplant-ineligible patients with NDMM, transition to IRd following 3 cycles of V-based induction was associated with a significantly longer DOT, higher ORR and a lower treatment discontinuation rate due to AEs (including PN), compared with continued V-based combination therapy. Numerical trends for 18- and 24-month PFS and OS favoring IRd were also observed. These results suggest that iCT from parenteral V-based therapy to all-oral IRd may improve outcomes in patients treated at US oncology clinics.

Long-term proteasome inhibitor-based treatment can improve outcomes for patients with multiple myeloma, but can be challenging to achieve with parenteral therapies in clinical practice.

This analysis compared effectiveness of in-class transition from parenteral bortezomib (V)-based induction to all-oral ixazomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone (IRd) therapy versus remaining on V-based combination therapy, in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM).

Patients who transitioned to IRd were participants in the US MM-6 study, and those who remained on V-based therapy were enrolled in the global, observational INSIGHT MM study.

Most patients (>90%) were treated in community oncology practices.

Overall response rate was significantly higher in patients who transitioned to IRd versus those who remained on V-based therapy (73.2 vs 57.5%; p < 0.0001).

After median follow-up periods of 20.3 and 15.8 months, respectively, the median duration of treatment was longer in the IRd cohort versus the V-based cohort (10.8 vs 5.3 months; p < 0.0001).

Transition to IRd resulted in a lower ixazomib treatment discontinuation rate due to adverse events (18%) compared with the V discontinuation rate in patients who continued to receive V-based combination therapy in the V-based cohort (24%).

These data suggest that transition from parenteral V-based therapy to all-oral IRd may improve outcomes in patients treated at US oncology clinics.

Transition to an oral treatment regimen may be particularly beneficial to patients with restricted mobility, those who prefer to remain outside of a hospital/clinic setting for treatments, or those with work commitments/family obligations.

The results of this analysis represent the diverse NDMM populations typically treated in clinical settings.

Author contributions

RM Rifkin and J Richter were members of the US MM-6 steering committee. RM Rifkin, CL Costello, R Abonour and HC Lee were members of the INSIGHT-MM steering committee. RM Rifkin, S Kambhampati, J Richter, R Abonour, M Stokes, DM Stull, D Cherepanov, K Bogard, SJ Noga and S Girnius contributed to the conception and design of the work. RM Rifkin, S Kambhampati, HC Lee, DM Stull, D Cherepanov, SJ Noga and S Girnius contributed to the acquisition of data. RM Rifkin, CL Costello, RE Birhiray, S Kambhampati, J Richter, HC Lee, M Stokes, K Ren, DM Stull, D Cherepanov, SJ Noga and S Girnius contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data. RM Rifkin, DM Stull, D Cherepanov and SJ Noga drafted the work. RM Rifkin, CL Costello, RE Birhiray, S Kambhampati, J Richter, R Abonour, HC Lee, M Stokes, K Ren, DM Stull, D Cherepanov, K Bogard, SJ Noga and S Girnius revised the work critically. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Writing disclosure

Medical writing support for the development of this manuscript, under the direction of the authors, was provided by Laura Webb, PhD, of Ashfield MedComms, an Inizio Company, funded by Takeda Pharmaceuticals, USA, Inc., Lexington, MA, and complied with the Good Publication Practice (GPP) guidelines (DeTora LM, et al. Ann Intern Med 2022;175:1298–1304).

Ethical conduct of research

US MM-6 was conducted in accordance with the International Council on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines, the ethical principles that have their origins in the Declaration of Helsinki, and applicable regulatory requirements. The local or central institutional review boards for each study center approved the study. All the patients gave written informed consent. INSIGHT MM was conducted in accordance with local ethical guidelines, European directives on protection of human patients in research, the Declaration of Helsinki, the European Network of Centres for Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacovigilance Guidelines, Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practice Guidelines and other local or national specific, relevant guidelines, laws or regulations. All patients were required to provide written informed consent before data collection, including authorization to use their patient medical records.

Supplemental Information 1

Download MS Word (248 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all patients and their families, as well as all investigators for their valuable contributions to these studies. They would also like to acknowledge P Whidden, MS, and K Tran, DO, MBA, for their contributions to the US MM-6 trial and manuscript preparation, and S Huse, BS, and YJ Kim, PhD, for their contributions to data analysis.

Supplementary data

To view the supplementary data that accompany this paper please visit the journal website at: www.futuremedicine.com/doi/suppl/10.2217/fon-2023-0272

Financial disclosures

These studies were funded by Takeda Development Center Americas, Inc. (TDCA), Lexington, MA. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Competing interests disclosure

RM Rifkin: Employment with McKesson; Ownership of stock/shares with McKesson; Member of advisory council/committees for Amgen, BMS, Coherus, Fresenius, and Takeda; CL Costello: Member of advisory council/committees for BMS, Janssen, Takeda, and Pfizer; RE Birhiray: Member of advisory council/committees for Array Biopharma, Lilly Oncology, Janssen Scientific Affairs, Epizyme, Tg Therapeutics, and Regeneron; Other financial relationship with Janssen Biotech, Amgen, Puma Biotechnology, Lilly USA, Incyte, Pharmacyclics (an Abbvie company), Genzyme, Dova/Sobi Pharmaceuticals, Exelixis, E.R. Squibb & Sons, Abbvie, AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Daichi Sancho, Morphosys, Regeneron, Glaxo Oncology, and Seagen; S Kambhampati: None; J Richter: Consulting fees from Takeda and BMS/Celgene; R Abonour: Member of advisory council/committees for Takeda, BMS, and Janssen; Honoraria from Takeda, BMS, Janssen, and GSK; Consulting fees from Takeda, BMS, Janssen, and GSK; Grants or funds from Takeda, BMS, Janssen, and GSK; HC Lee: Consulting fees from BMS, Celgene, Genentech, Karyopharm, Legend Biotech, GSK, Sanofi, Oncopeptides, Pfizer, Takeda, Allogene Therapeutics, Janssen Pharmaceutical; Grants or funds from BMS, Janssen, GSK, Takeda, Regeneron, Amgen; M Stokes: Employment with Evidera; Evidera received consulting fees from Takeda; K Ren: Employment with Takeda Development Center Americas, Inc. (TDCA); DM Stull: Employment with Takeda; Ownership of stock/shares with Takeda; D Cherepanov: Employment with Takeda; Ownership of stock/shares with Takeda; K Bogard: Employment with Takeda Oncology; SJ Noga: Employment with Takeda; S Girnius: Member of advisory council/committees for Takeda, BMS, Janssen, and GSK; Honoraria from Takeda, BMS, BeiGene, GSK and Adaptive. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Data availability statement

The authors certify that this manuscript reports the primary analysis of clinical trial data that have been shared with them, and that the use of this shared data is in accordance with the terms (if any) agreed upon their receipt. The source of this data, including the redacted study protocol, redacted statistical analysis plan, and individual participants’ data supporting the results reported in this article, will be made available from the completed studies within three months from initial request, to researchers who provide a methodologically sound proposal. The data will be provided after its de-identification, in compliance with applicable privacy laws, data protection and requirements for consent and anonymization.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Mateos MV , Richardson PG , Dimopoulos MA et al. Effect of cumulative bortezomib dose on survival in multiple myeloma patients receiving bortezomib-melphalan-prednisone in the Phase III VISTA study. Am. J. Hematol. 90(4), 314–319 (2015).

- Jimenez-Zepeda VH , Duggan P , Neri P , Tay J , Bahlis NJ . Bortezomib-containing regimens (BCR) for the treatment of non-transplant eligible multiple myeloma. Ann. Hematol. 96(3), 431–439 (2017).

- Facon T , Dimopoulos MA , Meuleman N et al. A simplified frailty scale predicts outcomes in transplant-ineligible patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma treated in the FIRST (MM-020) trial. Leukemia 34(1), 224–233 (2020).

- Richardson PG , San MJF , Moreau P et al. Interpreting clinical trial data in multiple myeloma: translating findings to the real-world setting. Blood Cancer J. 8(11), 109 (2018).

- Chari A , Romanus D , Palumbo A et al. Randomized clinical trial representativeness and outcomes in real-world patients: comparison of 6 hallmark randomized clinical trials of relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 20(1), 8–17; e16 (2020).

- Shah JJ , Abonour R , Gasparetto C et al. Analysis of common eligibility criteria of randomized controlled trials in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients and extrapolating outcomes. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 17(9), 575–583; e572 (2017).

- Manda S , Yimer HA , Noga SJ et al. Feasibility of long-term proteasome inhibition in multiple myeloma by in-class transition from bortezomib to ixazomib. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 20(11), e910–e925 (2020).

- Costello C , Davies FE , Cook G et al. INSIGHT MM: a large, global, prospective, non-interventional, real-world study of patients with multiple myeloma. Future Oncol. 15(13), 1411–1428 (2019).

- Rifkin RM , Costello CL , Birhiray RE et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Oral Ixazomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone (IRd) After Initial Bortezomib (V)-based Induction versus Parenteral V-based Therapy in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma (NDMM). Poster P947 presented at the 27th Congress of the European Hematology Association (EHA) 2022. Vienna, Austria (9–12 June 2022).

- Rifkin RM , Costello CL , Birhiray RE et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Oral Ixazomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone (IRd) After Initial Bortezomib (V)-based Induction versus Parenteral V-based Therapy in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma (NDMM). In: Abstract Book for the 27th Congress of the European Hematology Association. HemaSphere 6(Suppl. 3), 1605–1606 (2022).

- Nakaya A , Fujita S , Satake A et al. Impact of CRAB symptoms in survival of patients with symptomatic myeloma in novel agent Era. Hematol. Rep. 9(1), 6887 (2017).

- Thomas C , Thomas L . Renal failure–measuring the glomerular filtration rate. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 106(51-52), 849–854 (2009).

- Wilke T , Mueller S , Bauer S et al. Treatment of relapsed refractory multiple myeloma: which new PI-based combination treatments do patients prefer? Patient Prefer. Adherence 12, 2387–2396 (2018).

- Rifkin RM , Bell JA , DasMahapatra P et al. Treatment satisfaction and burden of illness in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Pharmacoecon. Open 4(3), 473–483 (2020).

- Chari A , Romanus D , DasMahapatra P et al. Patient-reported factors in treatment satisfaction in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM). Oncologist 24(11), 1479–1487 (2019).

- Moreau P , Masszi T , Grzasko N et al. Oral Ixazomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 374(17), 1621–1634 (2016).

- Durie BGM , Hoering A , Sexton R et al. Longer term follow-up of the randomized Phase III trial SWOG S0777: bortezomib, lenalidomide and dexamethasone vs. lenalidomide and dexamethasone in patients (Pts) with previously untreated multiple myeloma without an intent for immediate autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT). Blood Cancer J. 10(5), 53 (2020).

- Hungria VTM , Lee HC , Abonour R et al. Real-World (RW) Multiple Myeloma (MM) Patients (Pts) Remain Under-Represented in Clinical Trials Based on Standard Laboratory Parameters and Baseline Characteristics: Analysis of over 3,000 Pts from the Insight MM Global, Prospective, Observational Study. Blood 134(Suppl. 1), 1887–1887 (2019).

- Rifkin RM , Girnius SK , Noga SJ et al. In-class transition (iCT) of proteasome inhibitor-based therapy: a community approach to multiple myeloma management. Blood Cancer J.. 13(1), 147 (2023).

- Yu Y , Brown Wade N , Hwang AE et al. Variability in cytogenetic testing for multiple myeloma: a comprehensive analysis from across the United States. JCO Oncol. Pract. 16(10), e1169–e1180 (2020).

- Nunnelee J , Cottini F , Zhao Q et al. Early versus late discontinuation of maintenance therapy in multiple myeloma. J. Clin. Med. 11(19), (2022).