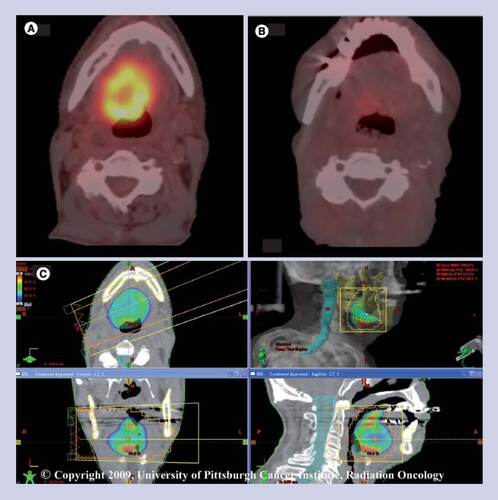

(A) Pretreatment positron-emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) demonstrates base of tongue recurrence. (B) Post-treatment PET-CT demonstrates complete response to stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) at 8 weeks. (C) SBRT plan prescribing 8.0 Gy/fraction to 80% isodose line.

© 2009, University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute, Radiation Oncology.

Cancers of the head and neck are the sixth most common malignancy worldwide with approximately 500,000 cases yearly. In the USA, an estimated incidence of 48,010 cases with 11,260 deaths are expected in 2009 Citation[1]. Despite major advances in the multidisciplinary, multimodality management of locally advanced head and neck cancers over the last two decades, locoregionally recurrent disease remains a significant problem for more than half the patients treated. The prognosis remains poor, with median survivals of 3–5 months with minimal treatment Citation[2] and 6–9 months with chemotherapy only Citation[3–6]. Surgical salvage remains the mainstay of therapy; however, many patients are frequently poor candidates for surgical salvage. Encasement of major vascular trunks, invasion of the prevertebral fascia or overall poor performance status are general contraindications to surgical salvage. It is for these patients that innovative approaches are needed to alter the dismal clinical outcomes reported in historical series. Chemotherapy has successfully been used for short-term palliation with reasonable success, with response rates reported as high as 50% Citation[7]. Unfortunately, disease recurrence can often occur quite promptly after discontinuation of therapy making this approach impractical for extended periods without impairing their quality of life (QOL). Similarly, attempts at re-irradiation have proved particularly challenging given the intolerance of tissue of the head and neck to a subsequent round of external beam radiation therapy.

Conventional re-irradiation outcomes

Although tempting when surgical salvage is not an option, re-irradiation is not without significant risk. Certainly, in select cases where small volume of disease is present, re-irradiation has been successful. These cases are rare and often fall into the realm of surgical salvage. More commonly seen are patients with disease involving multiple levels of the head and neck, critical structure or great vessels. Attempts at re-irradiation using 3D or intensity-modulation radiation therapy (IMRT) have been met with modest success, with local control rates of up to 50% and overall survival of approximately 20% at 5 years Citation[8–11]. Unfortunately, despite meticulous plan designs, normal tissue complication rates remain unacceptably high, with rates of up to 40% in some radiation schedules Citation[8,12]. These studies have shown a clear toxicity relationship between prior radiation dose, new radiation dose and volume of tissue re-irradiated. These data would seem to limit the dose of re-irradiation that can reasonably be delivered. This is frequently less than what is necessary to control the disease recurrence. Not surprisingly, historical rates of local and regional control of under 50% have been linked to inadequate doses at the time of re-treatment Citation[11].

Langer et al. reported the findings of a Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) Phase II trial in 2001 Citation[13]. Designed as a split-course schema of twice-daily radiation therapy concomitant with low-dose paclitaxel and cisplatin, RTOG 9911 showed significant responses, with median and 1-year progression-free survival of 7.8 months and 35%, respectively. Furthermore, the overall 1- and 2-year survival was 50% and 25%, respectively. Not surprisingly, however, grade 4 and 5 toxicities were common and occurred in 31% of patients making this regimen feasible, although not without significant high-grade toxicities. Others have sought to use interstitial brachytherapy for salvage. This is often performed in conjunction with surgical resection, therefore limiting applicability to a minority of patients. Studies like these, although promising, clearly demonstrated that the complex and yet important relationship between dose and volume of re-irradiated tissues is a major treatment-related complication. To overcome the limitations of conventional re-irradiation approaches, several researchers have proposed the use IMRT as a means to produce highly conformal dose distribution while simultaneously minimizing the dose to surrounding tissues. Typically, IMRT is delivered in 1.8–2.0 Gy per fraction once daily. Alternatively, others have reported hyperfractionated radiation therapy (1.5 Gy per fraction twice-daily) over a similar period. Unfortunately, similar to other conventional re-irradiation techniques, IMRT suffers from the prolonged time for administration, with treatment extending over 5–7 weeks or more. Furthermore, treatment breaks secondary to acute toxicities are a common occurrence with negative consequences on local control probabilities. In a series reported by Lu et al. the incidence of acute grade 2 or higher mucosal and salivary toxicities was 43% and 47%, respectively, which appears to be a slight improvement over other re-irradiation approaches Citation[14].

Stereotactic body radiation therapy

Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) is a technique by which a target, namely tumor recurrence, can be precisely localized using advanced imaging, such as positron-emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT), MRI and/or computed tomography (CT) with sub-millimeter accuracy. Building on concepts applied to the stereotactic treatment of brain tumors, linear-accelerator-based SBRT machines have been used to treat a variety of tumors throughout the body. SBRT has been established for the treatment of medically inoperable early stage lung cancer, liver and recurrent, previously irradiated spine tumors. Using this approach, in 2004 we reported one of the first experiences of SBRT for recurrent head and neck cancers Citation[15]. In that retrospective review of 22 unresected patients treated with a median dose of 24 Gy in five fractions, we found a 2-year local control rate and overall survival of 26% and 22%, respectively. Toxicities were remarkably absent, with acute mucositis occurring in only two patients. Encouraged by this early experience and challenged by the logistics of re-irradiation IMRT, a Phase I dose-escalation trial was designed to prospectively evaluation SBRT as a salvage strategy for medically inoperable recurrent head and neck cancers. In that study of recurrent, previously-irradiated tumors, a stepwise dose escalation schema was performed from 5.0 Gy per fraction to 8.8 Gy per fractions in five fractions delivered over 10 days. Of the 25 evaluable patients, a dose-limiting toxicity was not observed and the maximum tolerated dose was not reached up to 44 Gy in 5 fractions Citation[16]. A recent report by Henry Ford Hospital (MI, USA) examined the outcome in patients with primary, recurrent and metastatic tumors to the head and neck Citation[17]. They reported response rates based on tumor type – for example, primary, recurrent or metastatic. Patients were either treated with a single fraction of 14–18 Gy or fractioned at 36–48 Gy over six treatments. Reported median survival based on primary, recurrent and metastatic groups were 28.7, 6.7 and 5.6 months, respectively. Unfortunately, in the recurrent and metastatic group, the complete response rates remain dismal at 31 and 7%, respectively.

A larger review of 85 patients with recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck from the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute (PA, USA) has for the first time clearly demonstrated a dose–response relationship that was previously elusive in the SBRT literature for head and neck cancers Citation[18]. For tumors less than 25 cc, 40–44 Gy in five fractions appears to offer a statistically significantly greater chance for locoregional control. For tumors 25 cc or more there appears to be a continuation of a dose–response relationship without an appreciable plateau. In this study, a median survival of 11.5 months for all patients and 16.2 months for those free of metastatic disease was observed. The 1- and 2-year survival for patients with at least 6 months of follow-up was 69% and 42%, respectively. Grade 1 mucositis was the common acute side effect and grade 1 xerostomia the most common late effect. Surprisingly, there were no incidents of soft tissue necrosis or osteoradionecrosis.

It is important to note that meticulous planning and careful attention to detail are essential when pursuing a re-irradiation strategy, especially with SBRT. Since it is frequently difficult to differentiate scar tissue from recurrence, the use of multimodality imaging as well as other diagnostic studies is critical in properly delineating tumor-bearing areas. We have found PET-CT simulation quite valuable as it allows us the ability to accurately create the intended target for irradiation. Furthermore, its value in response assessment cannot be understated. In general, we have sought to keep the spinal cord dose below 8 Gy and limited the mandible dose to 20 Gy or less, the larynx 20 Gy or less and brainstem 8 Gy or less. demonstrates the example of a larger base of tongue recurrence on pre-SBRT PET-CT, the SBRT plan and the post-SBRT PET-CT obtained at 6 weeks. Note mild residual uptake in the base of the tongue indicating a near complete metabolic response.

Combination targeted therapies & SBRT

Despite promising results to date, there clearly remains an opportunity to improve control rates. Few studies have explored the role of chemotherapy in combination with conventional radiation therapy but this data is lacking in the SBRT literature. Given the markedly shortened course of SBRT, that is approximately 10 days, the efficacy of concurrent chemotherapy without an adjuvant course is doubtful. Furthermore, squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck are known to overexpress the cell surface marker EGF receptor. The differential overexpression of this cell surface receptor along with the availability of several monoclonal antibodies makes it a useful therapeutic target. Based on the remarkable results of cetuximab and conventional radiation therapy in the primary management of locally advanced head and neck cancers reported by Bonner et al., we sought to further improve the rates of responses, especially in larger tumors using this strategy Citation[19]. Using cetuximab (also known as C225, a monoclonal antibody) given at 400 mg/m2 on day -7, and 250 mg/m2 on days 0 and +7 along with SBRT. In a matched-pair analysis from our institution, there appears to be a local control and survival advantage. We saw a doubling of the median survival time in the cetuximab group when compared with the SBRT only group (24 vs 11 months), with an associated 24% reduction in risk of death [Unpublished data]. A Phase II clinical trial is currently accruing patients to further evaluate this regimen in a prospective manner.

Conclusion

Despite major advances in the management of locally advanced head and neck cancers, significant challenges remain. More than 50% of patients suffer disease recurrence, the majority of which will be locoregional in nature. Surgical resection remains the best chance for a cure in these patients but remains elusive for the majority of patients. In this setting, there is a great need for novel therapies to improve outcome without incurring a QOL penalty. The preponderance of the emerging data appears to suggest that highly focused re-irradiation strategies, such as SBRT, perhaps coupled with molecularly targeted agents (e.g., cetuximab), can produce durable responses at least in equal, if not greater, magnitude when compared with conventional re-irradiation strategies. Further refinement of patient- and tumor-specific characteristics will undoubtedly have a major impact on the outcomes for this challenging clinical problem.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The author has no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

Bibliography

- Jemal A , SiegelR, WardE, HaoY, XuJ, ThunMJ: Cancer Statistics 2009.CA Cancer J. Clin.59, 225–249 (2009).

- Stell PM : Survival times in end-stage head and neck cancer.Eur. J. Surg. Oncol.15, 407–410 (1989).

- Forastiere AA , MetchB, SchullerDEet al.: Randomised comparison of cisplatin plus fluorouracil and carboplatin plus fluorouracil versus methotrexate in advanced squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. A Southwest Oncology Group study.J. Clin. Oncol.10, 1245–1251 (1992).

- Vokes EE , MickR, KiesMSet al.: Pharmacodynamics of fluorouracil-based induction chemotherapy in advanced head and neck cancer.J. Clin. Oncol.14, 1663–1671 (1996).

- Clavel M , VermorkenJB, CognettiFet al.: Randomized comparison of cisplatin, methotrexate, bleomycin and vincristine (CABO) versus cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil (CF) versus cisplatin (C) in recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. A Phase III study of the EORTC Head and Neck Cancer Cooperative Group.Ann. Oncol.5, 521–526 (1994).

- Jacobs C , LymanG, Velez-GarciaEet al.: A Phase II randomized study comparing cisplatin and fluorouracil as single agents and in combination for advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. J. Clin. Oncol.10, 257–263 (1992).

- Karamouzis MV , FriedlandD, JohnsonR, RajasenanK, BranstetterB, ArgirisA: Phase II trial of pemetrexed (P) and bevacizumab (B) in patients (pts) with recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC): an interim analysis.J. Clin. Oncol.25(185), 6049 (2007).

- Pomp J , LevendagPC, Van PuttenWL: Reirradiation of recurrent tumors in the head and neck.Am. J. Clin. Oncol.11, 543–549 (1988).

- Emami B , PerezCA: Combination of surgery, irradiation, and hyperthermia in treatment of recurrences of malignant tumors.Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys.13, 611–613 (1987).

- Langlios D , EschwegeF, KramarA, RichardJM: Re-irradiation of recurrent tumors in the head and neck.Radiother. Oncol.3, 27–33 (1985).

- Salama JK , VokesEE, ChmuraSJet al.: Long-term outcome of concurrent chemotherapy and reirradiation for recurrent and second primary head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma.Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys.64, 382–391 (2006).

- Stevens KR Jr , BritschA, MossWT: High-dose re-irradiation of head and neck cancer with curative intent.Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys.29, 687–698 (1994).

- Langer CJ , HarrisJ, HorwitzEMet al.: Phase II study of low-dose paclitaxel and cisplatin in combination with split-course concomitant twice-daily reirradiation in recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: results of Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Protocol 9911.J. Clin. Oncol.25, 4800–4805 (2007).

- Lu TX , MaiWY, TehBSet al.: Initial experience using intensity-modulated radiotherapy for recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma.Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys.58, 682–687 (2004).

- Voynov G , HeronDE, BurtonSet al.: Frameless stereotactic radiosurgery for recurrent head and neck carcinoma.Technol. Cancer. Res. Treat.5, 529–535 (2006).

- Heron DE , FerrisRL, KaramouzisMet al.: Stereotactic body radiotherapy for recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: results of a Phase I dose-escalation trial.Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijrob.2008.12.075 (2009) (Epub ahead of print).

- Siddiqui F , PatelM, KhanMet al.: Stereotactic body radiation therapy for primary, recurrent, and metastatic tumor in the head-and-neck region.Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys.74, 1047–1053 (2009).

- Rwigema JC , HeronDE, FerrisRLet al.: Fractionated stereotactic body radiation therapy in the treatment of previously-irradiated recurrent head and neck carcinoma – updated report of the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Experience.Am. J. Clin. Oncol. (2009) (Epub ahead of print).

- Bonner JA , HarariPM, GiraltJet al.: Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck.N. Engl. J. Med.354, 567–578 (2006).