Abstract

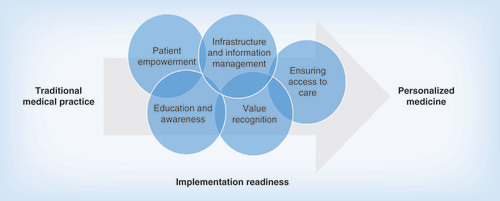

Aim: Research and innovation in personalized medicine are surging, however, its adoption into clinical practice is comparatively slow. We identify common challenges to the clinical adoption of personalized medicine and provide strategies for addressing these challenges. Methods: Our team developed a list of common challenges through a series of group discussions, surveys and interviews, and convened a national summit to discuss solutions for overcoming these challenges. We used a framework approach for thematic analysis. Results: We categorized challenges into five areas of need: education and awareness; patient empowerment; value recognition; infrastructure and information management; and ensuring access to care. We then developed strategies to address these challenges. Conclusion: In order for healthcare to transition into personalized medicine, it is necessary for stakeholders to build momentum by implementing a progression of strategies.

Personalized medicine is an evolving field in which physicians use diagnostic tests to identify specific biological markers, often genetic, that help determine which medical treatments and procedures will work best for each patient. By combining this information with an individual’s medical records and circumstances, personalized medicine allows doctors and patients to develop targeted treatment and prevention plans [Citation1,Citation2]. While there are many alternative terms for personalized medicine, including precision, individualized and stratified medicine, this report does not distinguish between those terms or attempt to reconcile differing definitions of each. Rather, the term personalized medicine is used throughout the report to describe the concept as defined above.

Research and innovation in personalized medicine are extensive and expanding, as measured by the number of scientific publications and a documented emphasis on genetic testing, health information management, biomarker discovery and targeted therapies [Citation3,Citation4]. The molecular diagnostics market is growing rapidly and diversifying. A recent report by NextGxDx estimated that nearly 4000 new diagnostic tests have been introduced to the market in 2015 [Citation5]. The same can be said for the molecular therapeutics market. In fact, 28% of all the medicines the US FDA approved in 2015 were personalized medicines [Citation6], and a recent study sponsored by the Personalized Medicine Coalition (PMC) and conducted by Tufts University demonstrates that 42% of all medicines and 73% of cancer medicines in development are potential personalized medicines [Citation7].

However, despite the steady increase in the number of clinically useful molecular diagnostics and targeted therapies, the healthcare system has been slow to integrate personalized medicine into clinical practice [Citation8–10]. Indeed, evidence suggests that in most cases, personalized medicine is not even discussed at the point of care. A recent public survey has shown that only four out of ten consumers are aware of personalized medicine, and only 11% of patients say their doctor has discussed or recommended personalized medicine treatment options to them [Citation11]. Behind this lag in clinical adoption are novel challenges that healthcare delivery systems are encountering as they adapt to the new requirements, practices and standards associated with the field [Citation12].

Background

Since the completion of the Human Genome Project in April 2003, there has been an increasing focus on genomics in medicine, coupled with efforts to help incorporate genomic information into healthcare practice. The US CDC established the Evaluation of Genomic Application in Practice and Prevention program in 2005 to evaluate genetic tests and other applications of genomic technology in transition from research to health practice [Citation13]. The Human Genome Research Institute’s Implementing Genomics in Practice Network addressed barriers to the integration of genomics into medicine and offered potential solutions [Citation14], and the Electronic Medical Records and Genomics Network has addressed the uptake of genetic information in electronic health record systems for genomic discovery and genomic medicine implementation research [Citation15]. The Clinical Genome Resource is currently developing interconnected community resources to improve understanding of genomic variation and its use in clinical care [Citation16]. At the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, an Institute of Medicine Roundtable on Translating Genomic-Based Research for Health issued workshop reports on “Integrating Large-Scale Genomic Information into Clinical Practice” [Citation17] and “Genomics-Enabled Learning Health Care Systems: Gathering and Using Genomic Information to Improve Patient Care and Research” [Citation18]. While this report focuses primarily on US healthcare institutions, clinical adoption of personalized medicine is advancing globally. For example, the Personalized Medicine 2020 and Beyond Strategic Research and Innovation Agenda included the development of an index of barriers for the implementation of personalized medicine and pharmacogenomics in Europe [Citation19]. Most recently, the Pharmacogenomics Knowledgebase and the Pharmacogenomics Research Network established the international Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium to help develop updated pharmacogenomics clinical practice guidelines [Citation20].

While these programs have facilitated a dialogue about how to incorporate genomic information into healthcare practice, recent surveys show that most healthcare organizations are unprepared to implement personalized medicine [Citation21] and some hospital systems may be putting implementation programs on hold [Citation22]. The barriers often involve knowledge gaps, system-wide process obstacles and resistance to the cultural changes necessary to move toward a more personalized care paradigm. Often, personalized medicine programs are working in isolation and therefore are not benefitting from the experiences of other healthcare delivery organizations.

PMC’s Healthcare Working Group (HWG) has identified common challenges involved in developing personalized medicine programs and the most promising strategies for addressing them. This article describes this initiative, which has provided a forum for healthcare delivery organizations to discuss integration of personalized medicine into clinical practice, highlighted basic principles, identified integration challenges, developed corresponding strategies to address challenges and outlined a roadmap to help foster cultural change in medical practices.

Methods

PMC’s Healthcare Working Group

PMC’s HWG is comprised of representatives from 49 organizations involved in healthcare delivery, including 19 academic health centers, 12 community healthcare systems, 16 healthcare delivery support organizations and two physician groups (Supplementary Material 1).

PMC conducted a survey of the HWG regarding concerns and challenges related to the development and implementation of personalized-medicine strategies in clinical practice. From that survey the group developed a set of principles and a list of significant common challenges encountered by healthcare delivery organizations. PMC then conducted semi-structured interviews with senior executives to provide details and distinguish the most significant challenges faced by providers of all types. The group reviewed and revised the principles and list of challenges through a series of teleconference discussions. Finally, PMC used a framework approach of qualitative research for thematic analyses.

Solutions

PMC coordinated a series of focus group discussions to discuss potential solutions for addressing the identified common challenges. The sessions included three separate discussions representing different stakeholders – providers (17 participants), industry (23 participants) and patients (14 participants). Focus group members participated on a volunteer basis. No compensation, individual or organizational attribution in this or any publication was provided. Each group answered a series of questions about strategies for addressing common challenges (see Supplementary Material 2 for a list of focus group questions). From the responses, PMC developed a list of strategies to tackle each challenge. Alongside its partner, the Biotechnology Innovation Organization, PMC then hosted a national meeting – Solutions Summit: Integration of Personalized Medicine into Health Care – on 14 October 2015, to discuss and refine the list of solutions. The Solutions Summit was sponsored in part by corporate and nonprofit organization partners: Alliance for Aging Research, AstraZeneca, CareDx, Foley Lardner LLP, Foundation Medicine, Johnson & Johnson, The National Pharmaceutical Council, Novartis, Pfizer and Vertex.

Results

Members of the HWG broadly reported that healthcare delivery systems are encountering novel challenges as they adapt to the new requirements and practices associated with personalized medicine. They identified five general areas of challenges:

Education and awareness;

Patient empowerment;

Value recognition;

Infrastructure and information management;

Ensuring access to care.

The group developed five principles for integrating personalized medicine into healthcare that correlate with each of these areas (Box 1). Various previous efforts to better understand and prioritize challenges to integrating personalized medicine into healthcare have identified similar categories. For example, in Europe and Canada, the Personalized Medicine 2020 and Beyond Strategic Research and Innovation Agenda categorized barriers to clinical adoption in the areas of stakeholder involvement; standardization; interoperable infrastructure; healthcare system; data and research; funding; and policy making [Citation23].

Certain obstacles are particularly common among healthcare delivery organizations. The HWG identified the most significant of these and assigned them to five categories corresponding with the five identified areas of need (Box 2). It is noted that the perspective, scope and magnitude of specific integration challenges sometimes differ between distinct types of healthcare delivery organizations, such as academic health centers and community hospitals. Thus, the HWG did not prioritize individual challenges, but rather emphasized that all of the common challenges are significant barriers to the integration of personalized medicine into clinical practice and identified the overarching priority as recognizing and addressing the need for a paradigm shift from traditional practice to personalized medicine.

Box 3 lists strategies organizations have implemented in part or in full to overcome the integration challenges. Organizations believe these strategies can be expanded nationally. The solutions are listed in categories corresponding with the five general areas of need. However, more specific descriptions of challenges were necessary to help provide clearer direction for potential action on particular solutions. These strategies are not meant to imply that healthcare delivery organizations must act alone in their implementation. On the contrary, many of the strategies involve developing evidence, building resources and/or partnering on policy activities with multiple stakeholder groups. The need for these collaborative solutions reflects perceived shortcomings of the current medical practice paradigm in which separate institutions advance priorities independently. These strategies thereby underline the need for a new paradigm.

Discussion

The evolution of healthcare delivery to personalized medicine requires making new knowledge available, placing a greater emphasis on patient perspectives, recognizing the value of molecular pathways in guiding care, building new infrastructure and information management processes and reshaping healthcare delivery to ensure access to personalized medicine technologies and services. Overcoming challenges in these areas will likely require near-term strategies to implement programs that are straightforward and can provide clear solutions as well as long-term strategies that can drive systemic and cultural change. However, with a clear understanding of the set of challenges and the best strategies for overcoming those challenges, a roadmap for healthcare systems to advance the personalized medicine paradigm can be built.

Education & awareness

Perhaps the greatest challenge to integrating personalized medicine into healthcare is a lack of education and awareness among patients and throughout the healthcare delivery community. The path forward in this area, however, might be the clearest and most straightforward. Freely available educational resources that provide necessary basic scientific explanations of personalized medicine principles as well as technology-specific details have been and are being developed by a number of organizations [Citation24–28]. When published online, these materials can be presented in multiple formats based on the needs of different stakeholders. However, they must be accurate, trusted and updated regularly. PMC continues to work with the personalized medicine community to develop a content-rich website that can serve as the ‘go-to’ source for personalized medicine knowledge [Citation29]. Other strategies to address education challenges include coordinating community forums to agree upon a common terminology regarding personalized medicine and to engage community leaders as well as patient support groups and healthcare delivery professionals to help promote personalized medicine and disseminate educational materials.

Although many community education strategies are clear, building awareness and knowledge will not be easy, especially with regard to physicians and other healthcare providers. In-person training and educational programs led by genetic experts can be made available that help ensure that provider’s knowledge is up-to-date regarding personalized medicine. Current medical and pharmacy school curricula can also be updated to reflect current medical concepts. While reaching an adequate level of awareness and education among all stakeholders will take time, strategies to address these challenges are straightforward and ready for implementation.

Patient empowerment

As we move forward, patients can be fully informed, both in terms of options for prevention or treatment of disease and efforts to protect their molecular information from being used in ways that would cause them concern, and perhaps, long-term repercussions, such as discrimination, job loss or loss of health insurance coverage. Patients can be involved in deciding how their data are used, particularly in an environment where care is managed across a number of specialized physicians (i.e., oncologist, cardiologist and rheumatologist, among others).

In these areas too, the way forward seems clear. Many health and research organizations in the public and private sectors are reconsidering current policies related to patient privacy and consent for the use of molecular information, such as the development of updated recommendations and policies on informed consent for participation in clinical research [Citation30–32]. Some providers are developing genetic counseling service policies to ensure that patients, early in their care, are able to understand their individual molecular information and its implications, so that they are able to make informed decisions regarding its disclosure and use before problems arise [Citation33–35]. Additionally, programs are being developed or are ready to be implemented that will establish the necessary partnerships among industry suppliers, providers, and patients and their families to ensure patient data are presented in ways that are meaningful and useful to each of these groups. Perhaps most importantly, practitioners are recognizing that they need to regularly and appropriately involve patients in their ongoing healthcare decision-making [Citation36]. Indeed, practitioners are increasingly recognizing that they have a duty to do so. Health systems can provide the necessary educational and consultation support that makes that possible, and information systems can be designed to ensure an appropriate role for patients.

Value recognition

While many stakeholders believe that personalized medicine can provide benefits to patients and the healthcare system, payers and providers are often reluctant to change policies and practices without convincing evidence of clinical and economic value [Citation3]. It is not clear how that evidence should be developed and disseminated for maximum impact. It is also not clear to healthcare delivery organizations how to develop profitable business models to support and sustain the delivery of personalized medicine.

However, strategies to include economic and clinical risk reduction end points within the body of evidence, in addition to patient survival and disease progression information, have begun to emerge and are much needed. Forums between payers and product developers, for example, may facilitate a better understanding of the evidence requirements necessary for positive coverage determinations. When generating evidence reports, product manufacturers can customize them for different audiences, such as payers, providers and clinical guideline developers. However, the personalized medicine value proposition increasingly depends on provider evidence generation. Providers decide which products and services to use and frequently must negotiate with payers to procure insurance coverage. The evidence that payers require to make coverage determinations for diagnostic tests is increasingly generated through analysis of clinical practice data. Thus, providers may consider collaborating directly with manufacturers and payers as part of a three-pronged approach to value determination.

To help facilitate an understanding of how personalized medicine can affect patient care, providers can establish proactive policies that incentivize practitioners to optimize treatments based on individual patient characteristics. However, as with insurance coverage, the facilitation of incentives for the delivery of personalized treatments will likely require practice-based evidence about their value. The need for evidence to facilitate policies that allow greater access to personalized medicine, contrasted with the need for access policies that enable evidence generation, has led to a challenging conundrum in demonstrating the value proposition. Both payers and providers would benefit from the implementation of a learning health system that provides a universally accepted and user-friendly way to systematically collect and share treatment and outcomes data. Implementing a learning health system would benefit from effective information management systems to aggregate and easily share clinical data for all patients, so as to analyze common patterns.

Infrastructure & information management

Effectively managing the massive amounts of information associated with personalized medicine and coordinating programmatic processes and services related to its use are also major areas of need. Many organizations are committed to overcoming challenges in these areas, but strategies need to be developed and implemented widely in order to have a meaningful impact on the larger healthcare system. Combining efforts can start by fostering a better understanding of different perspectives across stakeholder groups, encouraging more structured collaborations, and sharing experiences and best practices among healthcare organizations. Healthcare delivery organizations that have implemented personalized medicine programs and are working with information management organizations highlight the need for clear program leadership structures, effective processes for making programmatic decisions, and coordination of institutional personalized medicine program policies and processes across research and clinical programs. In consideration of this, improvements to electronic health records can be developed and implemented so that they include individual patients’ genetic information with built-in clinical support tools, describing potential clinical actionability. Biomarker and outcomes information can be standardized and interoperable across multiple health information technology platforms.

Ensuring access to care

Perhaps the most complex area of need is adapting health delivery approaches, processes and service structures to ensure access to personalized medicine. In many cases, overcoming challenges in this area requires cultural change as well as the implementation of new programs. Progress will likely require the shifting of the perspectives of many stakeholders toward a personalized medicine paradigm, which can be accelerated by improving the knowledge base, empowering patients, demonstrating value across stakeholder groups, and building effective program infrastructure and information management processes. Traditional fee-for-service practices can sometimes provide incentives for providers to deliver increased service volumes rather than identifying the best interventions for particular patients. Payer, provider and patient-directed policies to promote cultural change, such as developing incentives for payers to cover novel personalized medicine technologies with value-based evidence accumulation and defining value in terms of patient outcomes, could help accelerate progress. Guidelines and clinical support tools that are focused on the best care for individual patients can be regularly updated to include personalized medicine concepts and practices. Other practical strategies needed to begin breaking down the cultural barriers to personalized medicine, include removing disincentives for using new technologies that are of high value but are provided outside of network laboratories and making sure that professional fees for personalized medicine services and biomarker analysis are appropriate, both for the practitioner and the payer. Implementing these strategies will not suddenly change ingrained medical practice norms and culture, but will help contribute to an accelerating paradigm shift toward personalized medicine.

Study limitations

The strategies and recommendations listed in this report are generalized to all US healthcare delivery organizations and do not account for regional differences in care delivery or distinguish between academic health centers and community hospital systems. The primary differences between academic health centers and community hospitals are the availability of resources and the nature of institutional missions. Academic health centers often include both research and education in their missions and often have endowments and/or research grants. In these settings, support of research activities is recognized as vital to the delivery of high-quality healthcare. In contrast, community hospitals rarely include research and education in their missions and there can be a tension between research endeavors and clinical care. In these settings, the research programs that do take place typically favor translational research that will benefit a specific patient population and it can be difficult to attract external funding. Thus, it is important to consider the type of healthcare institution being evaluated when considering the strategies and recommendations presented here. For example, community hospital systems often ranked workforce education as a higher priority challenge than many academic health centers. Also, it is important to consider the regional context for the delivery of care. The types of challenges and their magnitude of impact on the adoption of personalized medicine can differ between urban and rural settings. For example, in some rural areas, the lack of access to high-speed internet continues to challenge education, e-learning and e-health programs, and adoption lags behind internet availability [Citation37]. There is also a growing rural/urban divide on compliance with “meaningful use” requirements pertaining to medical records [Citation38]. A description of specific case examples of various healthcare delivery organizations’ experiences in integrating personalized medicine into clinical practice might further elucidate these challenges.

The analysis of common challenges presented in this report is largely qualitative and is limited to discussion among participants in the HWG. The collective perspectives of the HWG members may differ from those of representatives at other healthcare delivery organizations. The analysis in this report consisted of polling members, informal survey and consensus review, and did not account for differing perspectives within the HWG or measure the strength of agreement related to particular challenges. A survey targeting the broader healthcare delivery community and consisting of rankings of challenges might be able to provide quantitative analytics that could be used to better distinguish between differing perspectives of various types of healthcare delivery organizations.

Conclusion

As the healthcare system makes the transition from its traditional, one-size-fits-all approach toward a personalized medicine paradigm, it will be necessary to overcome challenges in several areas. Some strategies involving activities, programs and policies, such as those related to education and awareness and patient empowerment, can be implemented now or in the near term. Other strategies will require stakeholders to overcome reluctance to reshaping traditional practices and may require a cultural change in the way medicine is approached. However, progress made in addressing challenges in the areas where strategies are most straightforward and for which solutions are clearest should help increase our understanding of what is necessary to address more difficult challenges in other areas, thereby setting up a progression of solutions, ultimately fostering behavioral change that drives adoption of personalized medicine (). For example, redesigning consent policies for the use of individual molecular data before problems arise and in a way that ensures patient privacy and data control could improve the process for collection and utilization of patient information for research and clinical care. Improved patient data processing would allow us to devise more effective strategies for community-wide information management, which could, in turn, help reshape medical practice approaches and processes.

Paradigm shifts requiring cultural change typically happen slowly and often face resistance. However, when a new paradigm provides clear advantages, there is counter pressure to accelerate a shift in culture. In this context, we offer this report as a roadmap for the implementation of integration strategies to add more momentum toward effecting cultural change and a paradigm shift toward personalized medicine.

Future perspective

Currently, several healthcare delivery organizations are actively engaged in implementing personalized medicine programs. Understanding and communicating which policies and processes have worked best for these early adopters will help other organizations as they design and implement their own personalized medicine programs. This report highlights the need for a progression of strategic programs and efforts that encourage a paradigm shift. Implementation of these strategies uses a systems approach interfacing multiple disciplines including molecular biology, epidemiology and public health [Citation39]. Basic strategic components to support personalized medicine could help foster system-wide directives and incentives that will be key to driving cultural change.

The initial stages of implementing personalized medicine programs will involve putting into practice strategies to address education and patient empowerment challenges while, at the same time, setting up appropriate leadership and forums to design and initiate programs and policies that will drive value recognition and effective infrastructure and information management. Implementing these strategies can position healthcare delivery organizations to address challenges related to adapting treatment approaches and processes that will ensure access to personalized medicine and thereby continue to usher in a new era of medicine.

Personalized medicine is a fundamental change in the way medicine is practiced and delivered. It strengthens prevention, diagnosis and therapeutic efforts through customized treatments appropriate for each patient. In order to integrate personalized medicine into healthcare practice, the following principles should be considered:

Healthcare providers, payers, employers and policymakers, as well as patients and their families, need to have a better understanding of personalized medicine concepts and technologies

Policies and practices related to patient engagement, privacy, data protections and other ethical, legal, and societal issues regarding the use of individual molecular information must ensure appropriate consent and be acceptable to patients

Best practices must be established for the collection and dissemination of evidence needed to demonstrate clinical utility of personalized medicine and ensure the recognition of its value to care

Effective healthcare delivery infrastructure and data management systems should be developed and applied so that individual patient and clinical support information is comprehensive, useful and user friendly, and so that it can be used to guide clinical decisions

Best practices for healthcare delivery approaches, processes and program operations that ensure access to personalized medicine must be established and implemented

Awareness & education

Variable terminologies exist for personalized medicine, leading to confusion

Consumer awareness is poor, and demand for products and services is relatively low:

The science is complex and often difficult to correlate with various personalized treatment options

Different consumers have different information needs and health literacy levels

Awareness and knowledge within the healthcare provider community is insufficient:

Knowledge resources are scarce, seldom used and are not regularly updated

Education efforts outside of oncology are uncommon

Information on personalized medicine practices, policies and community support is not readily available, or not being used

Workforce training for new technologies/techniques is insufficient

Medical school curricula on integrating genetics/genomics are often outdated

Patient empowerment

Patient consent policies for the use of molecular information are often confusing or inappropriate

Molecular information is often not secure and may be subject to hacking

Data sharing policies do not always take into consideration proprietary or privacy concerns

Providers do not adequately involve patients in their healthcare decision-making, and do not account for the level that a patient wants to be engaged in healthcare discussions:

Patient preferences in treatment and prevention strategies are not always considered

Patients and their families are often not appropriately counseled with regard to genomics

Racial, ethnic, economic and regional disparities are not appropriately addressed

Value recognition

It is unclear what evidence payers require to facilitate coverage

Payment rates for diagnostics are often not based on their value to care

Clinical and economic data demonstrating value are still emerging

It is unclear what evidence is necessary to convince doctors to clinically adopt new technologies and services:

Not all molecular variants are clinically actionable

Practice guidelines are slow to be updated

Healthcare organizations do not recognize the value of integrating personalized medicine to the institution:

The return on investment across the institution is not yet clear

Programmatic value that may not have an immediate return on investment is not well understood

Preventive care is often overlooked in practice

There are few incentives for sharing clinical data that could enhance the understanding of value, such as individual variability and outcomes data

Infrastructure & information management

Personalized medicine programs lack clear decision-making processes

Policies and processes are not always coordinated across the healthcare institution:

Communication across the continuum of care is insufficient or breaks down easily

Molecular information is not often coupled meaningfully within clinical support tools

Research is not well coordinated with clinical practice

Policies to better evaluate program efficiency and to implement adjustments are lacking

Laboratory services often operate in a silo

It is unclear what diagnostic tests can/should be run in-house versus being sent to external laboratories

Source factors are often not appropriately considered when making decisions regarding buying versus making diagnostic tests:

Projection of product volumes may be inaccurate considering new diagnostic and therapeutic needs

Information technology systems/platforms are unable to effectively manage exceptionally large amounts of individual molecular information

Molecular information collection, storage and analysis take more time than many physicians feel it is worth

Electronic health record information is not standards based and usually not interoperable

Individual molecular data are not effectively translated into evidence for clinical care

Biorepositories are often not effectively maintained or integrated with information systems

Ensuring access to care

Many high-value diagnostic tests or services are not covered by health insurance companies

Traditional fee-for-service processes provide a system-wide incentive for ordering services based on volume rather than value

Electronic health records do not easily incorporate genetic information

Some physicians are reluctant to adopt personalized medicine practices:

There is a perception that personalized medicine techniques require time without adequate compensation

There is a perception that it is too cumbersome to involve genetics experts/counselors in patient care

Clinical guidelines do not reflect current concepts in personalized medicine

Most clinical decision support tools are not equipped for integrating patient biomarker information in treatment decision-making

Serious adverse events/US FDA black box warnings related to targeted treatments are often misunderstood related to use in appropriate populations

Medical groups, community healthcare organizations and other outside stakeholders are often not coordinated with regard to personalized medicine programs and guidelines

Sustainable business models are yet to be developed

Products and services are not always available, particularly in rural settings, and many patients are reluctant or unable to travel to other health centers

Geneticists/genetic counselors/molecular pathologists are not always accessible, especially in rural settings

Awareness & education

Challenge: healthcare providers, payers, employers and policy-makers, as well as patients and their families, often have a poor or impractical understanding of personalized medicine:

Develop freely accessible online educational information that is presented in multiple formats based on the needs of different stakeholders

Organize collaborative forums to develop and agree upon a common lexicon regarding personalized medicine

Organize industry forums to develop and agree upon consistent themes for communications based on scientific evidence and value

Provide healthcare professional groups and patient support organizations with personalized medicine information and educational materials, and actively manage multiple communication and dissemination channels

Identify physician and community leaders to participate in regional events that raise awareness and promote personalized medicine

Engage pharmacists to help patients understand the molecular mechanisms of their disease and the benefits of personalized medicine technologies

Develop social media platforms to raise awareness of personalized medicine events, activities and new technologies

Update the current medical and pharmacy school curricula to holistically integrate concepts related to personalized medicine

Develop new personalized medicine Continuing Medical Education programs

Patient empowerment

Challenge: patients need to be proactively involved in their treatment decision-making, and in policy development related to information privacy, data protections and other ethical, legal and societal issues:

Include patient representatives in the development of proactive policies and practices related to patient protections and the use of individual molecular information

Implement state-of-the-art cybersecurity measures related to individual molecular information

Develop programs to explain diagnostic test results to patients; provide them with recommendations and easy access to related information and counseling

Provide counseling services to patients before ethical dilemmas arise

Incorporate patient-reported outcomes through multiple channels to capture and better understand patient experiences

Design clinical trials with diverse research participants that include persons of various ethnicities, races, ages and genders to better inform the value of a specific treatment option for any given patient

Value recognition

Challenge: payers and providers are unconvinced of the benefits of personalized medicine; evidence demonstrating its value to healthcare is still emerging:

Provide a forum for payers and the diagnostic and biopharmaceutical industries to discuss the health technology assessment process and evidence requirements necessary for coverage

Conduct economic impact studies that are meaningful to payers

Design clinical studies to serve multiple purposes, including regulatory approval, establishing clinical utility for payers and informing clinical guidelines; customize scientific and value-based evidence reports for different audiences (payer, provider, clinical guideline developers) based on their particular needs

Develop standards as well as measurable targets for comparative effectiveness research studies and coverage with evidence development programs

Design and implement research studies that demonstrate the cost and benefits of positive coverage decisions in areas of unmet need

Develop and implement proactive policies that incentivize healthcare providers for optimizing treatments based on individual patient characteristics

Include medical center and in-house provider laboratories in US Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services median pricing determination for a fairer market value for diagnostic tests

Facilitate a learning health system by developing an effective, universally accepted and user-friendly process to systematically collect and share treatment and outcomes data

Infrastructure & information management

Challenge: health system infrastructure and information management are not yet well equipped for handling the massive amounts and different kinds of information associated with personalized medicine:

Coordinate institutional policies and processes that assure effective communications through the continuum of care and across research and clinical programs, and develop an effective process for making programmatic decisions

Include each patient’s individual genetic data, as well as information regarding clinically actionable variants, within electronic health records

Assure that all medical data, clinical support and outcomes information are standardized and interoperable across multiple health information technology platforms

Develop and implement user-friendly platforms to input data, and provide clinical support information to physicians in a way that saves time and resources

Develop platforms that are easily customized for different clinicians based on the level of information that best suits them

Assure that clinical support information includes complicating factors such as previously failed treatment classes and contraindications, and is provided within the electronic health record in a way that is easily recognized and accessed by physicians

Incorporate adverse event reporting and link it to pharmacogenetic information on an individual and population-wide basis

Develop proactive policies to incentivize data sharing and facilitate real-time data exchange for learning health systems

Ensuring access to care

Challenge: healthcare systems processes and procedures are optimized for traditional trial-and-error and fee-for-service practices resulting in disincentives for the use of personalized medicine products and services:

Develop incentives for payers to cover novel technologies with value-based evidence accumulation

Develop policies that ensure clinical guidelines and support tools are focused on providing the best treatment strategies for individual patients and are regularly updated.

Develop policies that remove disincentives for using technologies that are high value but are provided outside of network laboratories

Ensure that professional fees for personalized medicine services and biomarker variant analyses are adequate

Ensure access to genetic analysis experts and counselors where appropriate (including virtual access when necessary) and that streamline the process for their inclusion in patient care

Develop and implement a healthcare system-wide approach to basket-studies/clinical trial enrollment based on molecular characteristics

Include personalized medicine principles and practices in alternative payment and delivery models

Integration of personalized medicine

Despite the steady increase in the number of clinically useful molecular diagnostics and targeted therapies, clinical adoption has been slow.

Behind this lag in clinical adoption are novel challenges that healthcare delivery systems are encountering as they adapt to the new requirements, practices and standards associated with the field.

Education & awareness

Healthcare providers, payers, employers and policymakers, as well as patients and their families, need to have a better understanding of personalized medicine concepts and technologies.

Patient empowerment

Policies and practices related to patient engagement, privacy, data protections, and other ethical, legal, and societal issues regarding the use of individual molecular information must ensure appropriate consent and be acceptable to patients.

Value recognition

Best practices must be established for the collection and dissemination of evidence needed to demonstrate clinical utility of personalized medicine and ensure the recognition of its value to care.

Infrastructure & information management

Effective healthcare delivery infrastructure and data management systems need to be developed and applied so that individual patient and clinical support information is comprehensive, useful and user-friendly, and so that it can be used to guide clinical decisions.

Processes for standardization of reported medical data, clinical support and outcomes information need to be developed so that information is exchangeable across multiple health IT platforms.

Access to care

Best practices for healthcare delivery approaches, processes and program operations that ensure access to personalized medicine must be established and implemented.

Practical strategies are needed to begin breaking down the cultural barriers to personalized medicine for the practitioner and the payer.

Roadmap for integration

As the healthcare system makes the transition toward a personalized medicine paradigm, it will be necessary to overcome challenges in several areas.

Some areas of challenges can be addressed through activities, programs and policies that can be implemented now or in the near term, while other areas will require a cultural change in the way medicine is approached.

Progress made in addressing challenges in education and patient empowerment can help accelerate strategies to overcome challenges in other areas, such as value recognition and information management.

As we increase our understanding of what is necessary to address more difficult challenges, there will likely be a progression of strategies, ultimately fostering behavioral change that drives adoption of personalized medicine.

Supplemental Material 1

Download MS Word (32.1 KB)Supplemental Material 2

Download MS Word (13.8 KB)Supplementary data

To view the supplementary data that accompany this paper please visit the journal website at: www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.2217/pme-2016-0064

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

- The Personalized Medicine Coalition . The basics ( 2016 ). www.personalizedmedicinecoalition.org/Education/The_Basics .

- The Personalized Medicine Coalition . The case for personalized medicine ( 2014 ). www.personalizedmedicinecoalition.org/Resources/The_Case_for_Personalized_Medicine .

- Novartis Oncology . The precision oncology annual trend report: perspectives from payers, oncologists, and pathologists ( 2016 ). www.hcp.novartis.com/care-management .

- Oxford Economics . Healthcare gets personal ( 2016 ). https://dam.sap.com/mac/preview/a/67/UmEUnxHHnJJzOOlUwAmnyXggPmAJJzgxUPAEmOXHxcwxPEPc/open20160412042800.htm .

- NextGxDx . The current landscape of genetic testing ( 2016 ). www.nextgxdx.com/insights .

- The Personalized Medicine Coalition . 2015 progress report: personalized medicine at FDA ( 2016 ). www.personalizedmedicinecoalition.org/Resources/2015_Progress_Report_Personalized_Medicine_at_FDA .

- The Personalized Medicine Coalition, PhRMA . Biopharmaceutical companies’ personalized medicine research yields innovative treatments for patients ( 2015 ). www.personalizedmedicinecoalition.org/Resources/PMCPhRMA_Report_Biopharmaceutical_Companies_Personalized_Medicine_Research .

- Aspinall MG , HamermeshRG . Realizing the promise of personalized medicine . Harvard Bus. Rev.85 ( 10 ), 108 – 117 ( 2007 ).

- Evans JP , MeslinEM , MarteauTM , CaufieldT . Deflating the genomic bubble . Science331 ( 6019 ), 861 – 862 ( 2011 ).

- ScienceDaily . Personalized medicine: moving forward slowly but surely ( 2008 ). www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/02/080211094056.htm .

- Miller AM , GarfieldS , WoodmanRC . Patient and provider readiness for personalized medicine . Pers. Med. Oncol.5 ( 4 ), 158 – 167 ( 2016 ).

- Manolio TA , ChisholmRL , OzenbergerBet al. Implementing genomic medicine in the clinic: the future is here . Genet. Med.15 ( 4 ), 258 – 267 ( 2013 ).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Office of Public Health Genomics . About EGAPP ( 2013 ). www.egappreviews.org/about.htm .

- National Human Genome Research Institute . Implementing Genomics in Practice (IGNITE) ( 2016 ). www.genome.gov/27554264/implementing-genomics-in-practice-ignite/ .

- National Human Genome Research Institute . Electronic Medical Records and Genomics (EMERGE) network ( 2016 ). www.genome.gov/27540473/electronic-medical-records-and-genomics-emerge-network/ .

- Institute of Medicine (US) . Integrating large-scale genomic information into clinical practice: workshop summary . National Academies Press , Washington, USA ( 2012 ). www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK91500/ .

- Rehm HL , BergJS , BrooksLDet al. ClinGen – the clinical genome resource . N. Engl. J. Med.372 ( 23 ), 2235 – 2242 ( 2015 ).

- Roundtable on Translating Genomic-Based Research for Health; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Institute of Medicine . Genomics-Enabled Learning Health Care Systems: Gathering and Using Genomic Information to Improve Patient Care and Research: Workshop Summary . National Academies Press , WA, DC, USA ( 2015 ).

- Horgan D , JansenM , LeyensLet al. An index of barriers for the implementation of personalized medicine and pharmacogenomics in Europe . Public Health Genomics17 , 287 – 298 ( 2014 ).

- PharmGKB . CPIC: Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium ( 2016 ). www.pharmgkb.org/page/cpic .

- PR Newswire . Survey: most healthcare organizations unprepared for precision medicine ( 2016 ). www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/survey-most-healthcare-organizations-unprepared-for-precision-medicine-300206860.html .

- Health Data Management . Many healthcare organizations not preparing for precision medicine ( 2016 ). www.healthdatamanagement.com/news/many-healthcare-organizations-not-preparing-for-precision-medicine .

- Horgan D , JansenM , LeyensLet al. An index of barriers for the implementation of personalized medicine and pharmacogenomics in Europe . Public Health Genomics17 , 287 – 298 ( 2014 ).

- Duke University School of Medicine . Applied genomics and precision medicine ( 2014 ). https://precisionmedicine.duke.edu/policy-resources/educational-resources .

- Coriell Personalized Medicine Collaborative . Understanding genetics ( 2016 ). https://cpmc.coriell.org/genetic-education/overview .

- American Nurses Association . Personalized medicine ( 2016 ). www.nursingworld.org/genetics .

- National Human Genome Research Institute . Education ( 2016 ). www.genome.gov/education/ .

- Mayo Clinic Center for Individualized Medicine . Genomics in patient care ( 2016 ). http://mayoresearch.mayo.edu/center-for-individualized-medicine/genomics-in-patient-care.asp .

- Personalized Medicine Coalition . Education ( 2016 ). www.personalizedmedicinecoalition.org/Education/The_Basics .

- Garrison NA , SatheNA , AntommariaAHMet al. A systematic literature review of individuals’ perspectives on broad consent and data sharing in the United States . Genet. Med.18 , 663 – 671 ( 2016 ).

- Bradbury AR , Patrick-MillerL , DomchekS . Multiplex genetic testing: reconsidering utility and informed consent in the era of next-generation sequencing . Genet. Med.17 , 97 – 98 ( 2015 ).

- Lorell BH , MikitaJS , AndersonA , HallinanZP , ForrestA . Informed consent in clinical research: consensus recommendations for reform identified by an expert interview panel . Clin. Trials12 ( 6 ), 692 – 695 ( 2015 ).

- GenomeWeb . NIH pumps $15M Into studies on effects of genomics information ( 2016 ). www.genomeweb.com/research-funding/nih-pumps-15m-studies-effects-genomics-information?utm_source=SilverpopMailing&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Daily%20News:%20Foundation%20Medicine%20Sues%20Guardant%20Health%20for%20Patent%20Infringement%20-%2005/18/2016%2011:00:00%20AM .

- Inova Translational Medicine Institute . MediMap PGx testing at Inova ( 2016 ). www.inova.org/itmi/medimap .

- BusinessWire . Cigna builds on three years of success, expands genetic counseling program ( 2015 ). www.businesswire.com/news/home/20160421006383/en/Cigna-Builds-Years-Success-Expands-Genetic-Counseling .

- Fowler FJ Jr , LevinCA , SepuchaKR . Informing and involving patients to improve the quality of medical decisions . Health Aff.30 ( 4 ), 699 – 706 ( 2011 ).

- LaRose R , GreggJL , StroverS , StraubhaarJ , CarpenterS . Closing the rural broadband gap: promoting adoption of the internet in rural America . Telecommun. Policy31 , 359 – 373 ( 2007 ).

- Sandefer RH , MarcDT , KleebergP . Meaningful use attestations among US hospitals: the growing rural-urban divide . Perspect. Health Inf. Manag.12 , f1 ( 2015 ).

- Nishi A , MilnerDA , GiovannucciELet al. Integration of molecular pathology, epidemiology and social science for global precision medicine . Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn.16 ( 1 ), 11 – 23 ( 2016 ).