Abstract

Aim: To investigate the relationship between effective fentanyl sublingual spray (FSS) doses for breakthrough cancer pain (BTCP) and around-the-clock (ATC) transdermal fentanyl patch (TFP). Methods: Adults tolerating ATC opioids received open-label FSS for 26 days, followed by a 26-day double-blind phase for patients achieving an effective dose (100–1600 µg). Results: Out of 50 patients on ATC TFP at baseline, 32 (64%) achieved an effective dose. FSS effective dose moderately correlated with mean TFP dose (r = 0.4; p = 0.03). Patient satisfaction increased during the study. Common adverse event included nausea (9%) and peripheral edema (9%). Conclusion: FSS can be safely titrated to an effective dose for BTCP in patients receiving ATC TFP as chronic cancer pain medication. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00538850

Patients with cancer-related pain may require around-the clock (ATC) opioid analgesics.

Despite ATC opioids, breakthrough cancer pain (BTCP) may necessitate the use of additional analgesics.

Fentanyl products such as the transdermal fentanyl patch and fentanyl sublingual spray may be prescribed to manage BTCP.

Treatment of cancer-related pain is complex and requires thorough understanding of the relationship between doses of concomitant medications and their analgesic and adverse effects.

The current study indicates a weak-to-moderate correlation between the effective dose of fentanyl sublingual spray used to treat BTCP and the effective dose of ATC transdermal fentanyl patch.

Initiating treatment with a low dose of a fentanyl sublingual spray and titrating upward to identify an effective dose may be an efficacious strategy for patients receiving ATC transdermal fentanyl patch and fentanyl sublingual fentanyl spray.

Fentanyl sublingual spray is generally well tolerated in patients receiving ATC transdermal fentanyl patch for BTCP.

First draft submitted: 7 December 2015; Accepted for publication: 3 January 2016; Published online: 29 March 2016

Persistent underlying pain in patients with cancer is effectively managed by around-the-clock (ATC) opioid analgesics; however, transient exacerbations of pain that occur spontaneously over the underlying pain, commonly described as breakthrough cancer pain (BTCP), can occur [Citation1,Citation2]. BTCP is reported by 15–100% of patients with cancer depending on the clinical setting and patient population studied [Citation3–9]. In a systematic review of 19 observational studies, the overall pooled prevalence of BTCP was approximately 60% [Citation9]. Because of its rapid onset, frequency, moderate-to-severe intensity, interpatient variability in pain intensity and short duration, BTCP is often difficult to manage [Citation10–12]. Therefore, managing BTCP requires comprehensive assessment of the patient’s pain to provide optimal treatment.

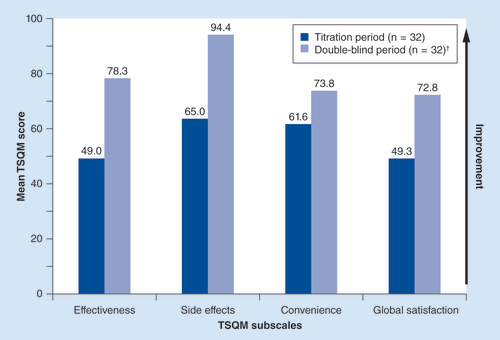

†Side effects, convenience and global satisfaction data not available for one double-blind period patient.

TSQM: Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication.

Fentanyl, a µ-opioid receptor agonist with approximately 80- to 100-fold higher potency than morphine, has been prescribed as an effective analgesic for pain in patients with cancer [Citation13,Citation14]. For moderate-to-severe underlying cancer pain, patients who do not achieve adequate analgesia or have unmanageable adverse events (AEs) with morphine, hydromorphone or oxycodone may be treated with fentanyl products (transdermal fentanyl patch) for ATC analgesia [Citation2,Citation15–16]. As well, for BTCP, oral transmucosal fentanyl formulations (such as fentanyl sublingual spray) are commonly prescribed because of a rapid onset of effect with fentanyl and the noninvasive routes of administration [Citation17,Citation18]. Compared with morphine treatment for BTCP, treatment with a transmucosal immediate-release sublingual fentanyl formulation was associated with lower mean pain intensity levels experienced by the patients, a shorter mean time to titrate to an effective dose and higher patient satisfaction with BTCP treatment [Citation19].

As well, a fentanyl sublingual spray formulation administered for BTCP has been shown to be efficacious and well tolerated [Citation20–23] and produce a significantly greater reduction in pain intensity versus placebo as early as 5 min after dosing, with a duration of 60 min (the last time interval assessed) [Citation20]. A sublingual administration route may provide more rapid onset of action versus other BTCP treatment routes of administration because of the high permeability and more available blood supply to the sublingual cavity relative to the oral route [Citation24]. In addition, the hepatic first-pass elimination of the drug is avoided as the sublingual venous drainage is systemic instead of portal [Citation25].

Therefore, a population of patients with cancer may be receiving an ATC fentanyl product and receive a BTCP-prescribed fentanyl formulation. Because of the inherent polypharmacy involved with cancer management, analgesic combinations that provide predictable results to manage both ATC pain and BTCP are highly desirable treatment strategies for this patient population. Traditional strategy for finding an effective dose of transmucosal formulations of fentanyl for BTCP is to start at a low dose and titrate upward until a dose that adequately balances efficacy and tolerability is reached [Citation2]. However, in patients treated with transdermal fentanyl patch for underlying cancer pain and fentanyl sublingual spray for BTCP, the relationship between the dose of fentanyl sublingual spray and the dose of transdermal fentanyl patch is unknown. There is a need to better understand the administration of these two fentanyl-based treatments with respect to initiation, titration and tolerability. In this post hoc analysis, we investigated the safety and the relationship between the effective doses of fentanyl sublingual spray for BTCP and ATC transdermal fentanyl patch in patients receiving both fentanyl products.

Methods

• Study design

This was a Phase III, multicenter, randomized placebo-controlled trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00538850). Details on the study design of this trial have been previously published [Citation20,Citation26]. Briefly, the study consisted of a screening period (up to 35 days), an open-label titration period (up to 26 days), a double-blind treatment period (up to 26 days) and a final visit after either completion of the double-blind period or study withdrawal. During the titration period, patients received treatment with fentanyl sublingual spray at a starting dose of 100 µg, titrated upward to 200, 400, 600, 800, 1200 and 1600 µg until an effective dose was achieved; the dose titration procedure has been previously described [Citation26]. Higher starting doses were permitted for patients who had previously used an oral transmucosal fentanyl product for BTCP (after a mandatory 7-day washout period), according to a predetermined dose-titration plan. Effective dose, defined as the lowest dose that provided adequate analgesia with tolerable AEs over two consecutive episodes of BTCP, which was established during the titration period, was used in the double-blind treatment period. During the double-blind period, patients were provided with ten blinded study medication doses sequentially numbered (seven fentanyl sublingual spray doses and three placebo doses in random order) for the treatment of ten episodes of BTCP. The Phase III study was approved by institutional review boards or independent ethics committees at all participating sites. The trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and all patients provided written informed consent.

• Patient population

Opioid-tolerant patients ≥18 years of age with cancer receiving ATC opioids for baseline pain (no more than moderate in severity), with one to four episodes per day of BTCP, were enrolled [Citation20]. Opioid tolerance was defined as receiving ≥60 mg/day oral morphine, ≥25 µg/h transdermal fentanyl, ≥30 mg/day oral oxycodone, ≥8 mg/day oral hydromorphone or an equianalgesic dose of another opioid analgesic for ≥1 week. Patients with uncontrolled or rapidly escalating pain or a medical or psychiatric condition that could interfere with the effects of the study medication or exacerbate opioid-related AEs were excluded. Patients were also excluded if they received investigational study product(s) ≤30 days before or monoamine oxidase inhibitors within 14 days of screening visit.

• Assessments

BTCP episodes, pain relief and AEs were assessed during daily telephone consultations, and dose adjustments were made according to the patient’s response to treatment. Treatment satisfaction was assessed at baseline (before the first titration dose of fentanyl sublingual spray) and at the end of the titration period by administering the Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM) [Citation27]. The TSQM is a 14-item scale that measures treatment satisfaction based on effectiveness, side effects, convenience and global satisfaction. Treatment satisfaction was determined as a score of ≥5 on a 7-point scale (1 = extremely dissatisfied; 7 = extremely satisfied). Patients were instructed to base their responses on the use of their usual supplemental medication and fentanyl sublingual spray for BTCP at baseline and at the post-titration assessment, respectively. Safety assessments included monitoring of AEs. A serious AE was defined as the following: mortality; considered life-threatening or jeopardized the patient and required intervention to prevent a life-threatening outcome; resulted in hospitalization or prolongation of an existing hospitalization; resulted in persistent or significant disability or incapacity; or a congenital abnormality or birth defect.

• Statistical analyses

Post hoc analysis of the subgroup of patients who received ATC transdermal fentanyl patch for underlying cancer pain during the titration phase was performed for treatment satisfaction (using TSQM) and safety (monitoring of AEs). The titration population included all patients who received ≥1 dose of fentanyl sublingual spray during the open-label titration period. The intent-to-treat (ITT) population included all randomized patients in the double-blind period who received study medication and had ≥1 subsequent pain assessment. Safety was assessed during the open-label titration period in the titration population and the double-blind period for the ITT population, who were subgrouped for ATC transdermal fentanyl patch use or other ATC medication use. Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated to assess the relationship between the mean effective dose of fentanyl sublingual spray and the final transdermal fentanyl dose during the titration phase.

Results

• Patient disposition & demographics

Out of the 130 patients treated during the open-label titration period, 50 patients were receiving ATC transdermal fentanyl patch for underlying cancer pain (). Most patients were male (58.0%) and white (90%). Thirty-two of the 50 patients (64.0%) who were on ATC transdermal fentanyl patch at baseline achieved an effective dose of sublingual fentanyl spray, entered the double-blind period and were included in the ITT population. The mean baseline transdermal fentanyl patch dose in patients who achieved effective fentanyl sublingual spray dose at the beginning of the double-blind period was 81.4 µg. The remaining 18 of 50 (36.0%) patients did not enter the double-blind period, and the mean baseline transdermal fentanyl patch dose in these patients was 75.4 µg. Reasons for discontinuations were patient decision (seven patients), AEs (five patients), intercurrent illness (one patient), protocol violation (one patient) or other reasons (two patients). Two patients entered the double-blind study but were not included in the ITT population because of lack of adequate efficacy assessments.

• BTCP episodes

During the titration period, patients on an ATC transdermal fentanyl patch had a mean of 2.4 BTCP episodes per day (range: 1.0–12.0; n = 49), and patients on an ATC transdermal fentanyl patch who did not enter the double-blind period had a mean daily number of BTCP episodes of 2.7 (range: 1.0–12.0; n = 17). The mean daily number of BTCP episodes during the double-blind period was 2.3 (range: 1.0–5.0; n = 32).

• Relationship between ATC transdermal fentanyl patch dose & effective dose of fentanyl sublingual spray

The distribution of final transdermal fentanyl patch doses during the titration phase and the mean effective fentanyl sublingual spray doses during double-blind treatment are shown in . The mean effective dose of fentanyl sublingual spray during the titration phase was 893.8 µg; 91% (n = 29) of patients were effectively treated with a mean dose in the range of 550–1000 µg. The effective dose of fentanyl sublingual spray only weakly to moderately correlated with the mean transdermal fentanyl patch dose (r = 0.4; p = 0.03).

• Treatment satisfaction & safety

The mean scores for all domains of TSQM – effectiveness, side effects, convenience and global satisfaction – increased from baseline of the titration period to baseline of the double-blind period in the ITT population for patients receiving ATC fentanyl patch (). Because of the rapid onset of BTCP, patient satisfaction with the time it takes a medication to start working (i.e., onset of effect), part of the effectiveness domain, is important to assess. Satisfaction with onset of effect at baseline of the titration period (i.e., prior to BTCP medication) was only reported in 7 (21.9%) of 32 patients. However, at baseline of the double-blind period (end of fentanyl sublingual spray dose titration), 29 (90.6%) of 32 patients reported satisfaction with onset of action.

In total, 33 of 50 (66.0%) and 19 of 32 (59.4%) patients receiving ATC transdermal fentanyl patch reported AEs during the open-label titration period and double-blind period of the study, respectively. During the open-label titration period, the most common AEs reported by patients receiving ATC transdermal fentanyl patch were peripheral edema (12.0%) and nausea (10.0%; ). Serious AEs were reported in 5 (10.0%) patients; these included gastrointestinal AEs (four patients; abdominal pain [two patients], nausea [one patient], and vomiting [one patient]), cellulitis (two patients), malignant neoplasm progression (one patient), and tachycardia (one patient). During the double-blind period, the most common AEs reported by patients receiving ATC transdermal fentanyl patch were peripheral edema (9.4%) and nausea (9.4%). Serious AEs were reported in 3 (9.4%) patients; these included gastrointestinal AEs (three patients; one patient each for abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting), tachycardia (one patient) and cellulitis (one patient). None of the serious AEs reported during both periods of the study were considered by the investigator to be related to the study drug. No opioid overdoses were reported during the entire study. The safety profile of patients receiving transdermal fentanyl patch versus other medications for ATC pain in patients receiving fentanyl sublingual spray for BTCP was comparable throughout the study.

Discussion

Fentanyl, a synthetic opioid, has been prescribed for managing both persistent underlying pain and BTCP in patients with cancer [Citation13,Citation15–17]. The lipophilicity of fentanyl allows for its transdermal administration for the management of persistent cancer pain, and its rapid and efficient analgesic action when administered as a transmucosal formulation makes it a suitable treatment for the management of BTCP [Citation1–2,Citation15]. The transmucosal formulation, fentanyl sublingual spray, offers rapid drug absorption and has a short duration of action, noninvasive administration route and tolerable safety profile [Citation1,Citation20,Citation28–29]. As patients with cancer experience polypharmacy, the use of a transmucosal fentanyl formulation for BTCP in patients with cancer already receiving a transdermal fentanyl patch for managing underlying pain can simplify the pain management aspect of their treatment. For example, healthcare providers can titrate fentanyl sublingual spray, starting with a low dose and titrating upward, to an effective dose for BTCP without concerns or modification of titration algorithm because of concomitant transdermal fentanyl patch use.

In this post hoc analysis, the relationship between the effective dose of fentanyl sublingual spray for BTCP and doses of the ATC transdermal fentanyl patch in patients receiving both fentanyl products was investigated during the open-label titration phase of a fentanyl sublingual spray clinical trial [Citation20]. This analysis found a weak-to-moderate correlation between the effective dose of fentanyl sublingual spray used to treat BTCP and the effective doses of ATC transdermal fentanyl patch in patients who received both these agents to manage cancer pain (~40%). Studies with other fentanyl transmucosal formulations are consistent with this result, suggesting that choosing the initial dose of a BTCP opioid based on the current ATC dose is not supported by the published data [Citation30,Citation31]. However, there has been a study suggesting doses of a transmucosal immediate-release buccal fentanyl formulation proportional to a patient’s ATC opioid regimen was more efficacious than oral morphine during the first 30 min post-treatment [Citation32]. Another approach calculated the dose of a transmucosal immediate-release sublingual fentanyl formulation for BTCP from a precalculated morphine dose for BTCP and found that a conversion ratio of 1/50 provided efficacious analgesia [Citation33]. In the current study, initiating treatment with a low dose of a fentanyl sublingual spray and titrating upward to identify an effective dose, was found to be an efficacious strategy for patients receiving ATC transdermal fentanyl patch. This is consistent with the current product labeling [Citation18] and is recommended for patients initiating therapy with transmucosal fentanyl therapies.

The current study supports that fentanyl sublingual spray is efficacious in managing BTCP and is generally well tolerated in patients receiving ATC transdermal fentanyl patch. During open-label treatment, fentanyl sublingual spray improved all four domains of the TSQM from baseline in patients who received ATC transdermal fentanyl patch, similar to results observed in the overall population (i.e., patients receiving any opioid analgesic as ATC medication for underlying cancer pain) [Citation20]. Among patients receiving fentanyl sublingual spray for BTCP, the AE profile of patients receiving transdermal fentanyl patch were generally comparable to patients receiving other opioids as ATC medication to control underlying cancer pain.

The post hoc nature and small number of patients are limitations of this study. However, these results are considered exploratory and warrant further evaluation in a prospective study. In conclusion, fentanyl sublingual spray can be safely titrated to an effective dose for BTCP in patients receiving transdermal fentanyl patch as ATC medication for underlying cancer pain.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that FSS dose only weakly to moderately correlated with doses of TFP ATC therapy used by patients with BTCP, thereby reiterating the importance of individual titration of FSS in patients with BTCP who are receiving ATC therapy. Healthcare providers should consider initiating fentanyl sublingual spray at a low dose and titrating up until an effective dose is reached.

Table 1. Demographics and baseline characteristics of patients receiving around-the-clock transdermal fentanyl patch (titration and intent-to-treat populations).

Table 2. Distribution of final transdermal fentanyl doses in relation to mean effective fentanyl sublingual spray doses.

Table 3. Adverse events† during open-label titration period (titration population) and double-blind period (intent-to-treat population).

Financial & competing interests disclosure

D Alberts has had a consulting or advisory role with Insys Therapeutics, Inc. (consultant, clinical research and drug development). CC Smith and N Parikh are employees of and hold stock in Insys Therapeutics, Inc. R Rauck has had a consulting or advisory role or received research funding from Medtronic, Inc., Medasys, Inc., the Alfred Mann Foundation, Archimedes, BioDelivery Sciences International, Inc., Meda and Jazz Pharmaceuticals, has been on speakers’ bureau for Jazz Pharmaceuticals and has received research funding from Alfred Mann Foundation, Bioness, Boston Scientific, Collegium Pharmaceuticals, CNS Therapeutics, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Medtronic, Myoscience, NeurAxon, Inc., Spinal Restoration, Spinal Modulation and St Jude Medical. Funding for this study was provided by Insys Therapeutics, Inc., Chandler, AZ, USA. Two employees of the sponsor participated as authors of this study. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Technical editorial and medical writing assistance, under the direction of the authors, was provided by Mary Beth Moncrief, and Pratibha Hebbar, Synchrony Medical, LLC, West Chester, PA, USA. Funding for this support was provided by Insys Therapeutics, Inc.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Taylor DR . Single-dose fentanyl sublingual spray for breakthrough cancer pain . Clin. Pharmacol.5 , 131 – 141 ( 2013 ).

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network . NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology (NCCN Guidelines®): adult cancer pain . National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. , Fort Washington, PA, USA ( 2014 ). http://oralcancerfoundation.org/treatment/pdf/pain.pdf .

- Portenoy RK , HagenNA . Breakthrough pain: definition, prevalence and characteristics . Pain41 ( 3 ), 273 – 281 ( 1990 ).

- Fine PG , BuschMA . Characterization of breakthrough pain by hospice patients and their caregivers . J. Pain Symptom Manage.16 ( 3 ), 179 – 183 ( 1998 ).

- Portenoy RK , PayneD , JacobsenP . Breakthrough pain: characteristics and impact in patients with cancer pain . Pain81 ( 1–2 ), 129 – 134 ( 1999 ).

- Zeppetella G , O’DohertyCA , CollinsS . Prevalence and characteristics of breakthrough pain in cancer patients admitted to a hospice . J. Pain Symptom Manage.20 ( 2 ), 87 – 92 ( 2000 ).

- Caraceni A , MartiniC , ZeccaEet al. Breakthrough pain characteristics and syndromes in patients with cancer pain. An international survey . Palliat. Med.18 ( 3 ), 177 – 183 ( 2004 ).

- Hwang SS , ChangVT , KasimisB . Cancer breakthrough pain characteristics and responses to treatment at a VA medical center . Pain101 ( 1–2 ), 55 – 64 ( 2003 ).

- Deandrea S , CorliO , ConsonniD , VillaniW , GrecoMT , ApoloneG . Prevalence of breakthrough cancer pain: a systematic review and a pooled analysis of published literature . J. Pain Symptom Manage.47 ( 1 ), 57 – 76 ( 2014 ).

- Portenoy RK , BrunsD , ShoemakerB , ShoemakerSA . Breakthrough pain in community-dwelling patients with cancer pain and noncancer pain, part 1: prevalence and characteristics . J. Opioid Manag.6 ( 2 ), 97 – 108 ( 2010 ).

- Davies A , ZeppetellaG , AndersenSet al. Multi-centre European study of breakthrough cancer pain: pain characteristics and patient perceptions of current and potential management strategies . Eur. J. Pain15 ( 7 ), 756 – 763 ( 2011 ).

- Burton AW , FilbetM , KnightAD , TayiR , PerelmanM . An analysis of the variability of breakthrough pain intensity in patients with cancer . J Community Support. Oncol.12 ( 3 ), 99 – 103 ( 2014 ).

- Prommer E . The role of fentanyl in cancer-related pain . J. Palliat. Med.12 ( 10 ), 947 – 954 ( 2009 ).

- Pereira J , LawlorP , ViganoA , DorganM , BrueraE . Equianalgesic dose ratios for opioids: a critical review and proposals for long-term dosing . J. Pain Symptom Manage.22 ( 2 ), 672 – 687 ( 2001 ).

- Kornick CA , Santiago-PalmaJ , MorylN , PayneR , ObbensEA . Benefit-risk assessment of transdermal fentanyl for the treatment of chronic pain . Drug Saf.26 ( 13 ), 951 – 973 ( 2003 ).

- Donner B , ZenzM , StrumpfM , RaberM . Long-term treatment of cancer pain with transdermal fentanyl . J. Pain Symptom Manage.15 ( 3 ), 168 – 175 ( 1998 ).

- Davis MP . Fentanyl for breakthrough pain: a systematic review . Expert Rev. Neurother.11 ( 8 ), 1197 – 1216 ( 2011 ).

- Subsys (fentanyl sublingual spray), CII, package insert . INSYS Therapeutics, Inc. , Chandler, AZ, USA ( 2014 ).

- Rivera IV , MunozGarrido JC , VelascoPG , Ximenezde Enciso IE , ClavaranaLV . Efficacy of sublingual fentanyl vs. oral morphine for cancer-related breakthrough pain . Adv. Ther.31 ( 1 ), 107 – 117 ( 2014 ).

- Rauck R , ReynoldsL , GeachJet al. Efficacy and safety of fentanyl sublingual spray for the treatment of breakthrough cancer pain: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study . Curr. Med. Res. Opin.28 ( 5 ), 859 – 870 ( 2012 ).

- Rauck R , ParikhN , DillahaL , BarkerJ , StearnsL . Patient satisfaction with fentanyl sublingual spray in opioid-tolerant patients with breakthrough cancer pain . Pain Pract.15 ( 6 ), 554 – 563 ( 2015 ).

- Rauck R , BullJ , ParikhN , DillahaL , StearnsL . Effective dose titration of fentanyl sublingual spray in patients with breakthrough cancer pain . Pain Pract. doi:10.1111/papr.12360 ( 2015 ) ( Epub ahead of print ).

- Minkowitz H , BullJ , BrownlowRC , ParikhN , RauckR . Long-term safety of fentanyl sublingual spray in opioid-tolerant patients with breakthrough cancer pain . Support Care Cancer doi:10.1007/s00520-015-3056-3 ( 2016 ) ( Epub ahead of print ).

- Harris D , RobinsonJR . Drug delivery via the mucous membranes of the oral cavity . J. Pharm. Sci.81 ( 1 ), 1 – 10 ( 1992 ).

- Stevens RA , GhaziSM . Routes of opioid analgesic therapy in the management of cancer pain . Cancer Control7 ( 2 ), 132 – 141 ( 2000 ).

- Nalamachu SR , ParikhN , DillahaL , RauckR . Lack of correlation between the effective dose of fentanyl sublingual spray for breakthrough cancer pain and the around-the-clock opioid dose . J. Opioid Manag.10 ( 4 ), 247 – 254 ( 2014 ).

- Atkinson MJ , SinhaA , HassSLet al. Validation of a general measure of treatment satisfaction, the Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM), using a national panel study of chronic disease . Health Qual. Life Outcomes2 , 12 ( 2004 ).

- Parikh N , GoskondaV , ChavanA , DillahaL . Single-dose pharmacokinetics of fentanyl sublingual spray and oral transmucosal fentanyl citrate in healthy volunteers: a randomized crossover study . Clin. Ther.35 ( 3 ), 236 – 243 ( 2013 ).

- Parikh N , GoskondaV , ChavanA , DillahaL . Pharmacokinetics and dose proportionality of fentanyl sublingual spray: a single-dose 5-way crossover study . Clin. Drug Investig.33 ( 6 ), 391 – 400 ( 2013 ).

- Nalamachu SR , RauckRL , WallaceMS , HassmanD , HowellJ . Successful dose finding with sublingual fentanyl tablet: combined results from 2 open-label titration studies . Pain Pract.12 ( 6 ), 449 – 456 ( 2012 ).

- Hagen NA , FisherK , VictorinoC , FarrarJT . A titration strategy is needed to manage breakthrough cancer pain effectively: observations from data pooled from three clinical trials . J. Palliat. Med.10 ( 1 ), 47 – 55 ( 2007 ).

- Mercadante S , AdileC , CuomoAet al. Fentanyl buccal tablet vs. oral morphine in doses proportional to the basal opioid regimen for the management of breakthrough cancer pain: a randomized, crossover, comparison study . J. Pain Symptom Manage.50 ( 5 ), 579 – 586 ( 2015 ).

- Shimoyama N , GomyoI , TeramotoOet al. Efficacy and safety of sublingual fentanyl orally disintegrating tablet at doses determined from oral morphine rescue doses in the treatment of breakthrough cancer pain . Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol.45 ( 2 ), 189 – 196 ( 2015 ).