Abstract

Aim: To identify the 3-month incidence of chronic postsurgical pain and long-term opioid use in patients at the Toronto General Hospital. Methods: 200 consecutive patients presenting for elective major surgery completed standardized questionnaires by telephone at 3 months after surgery. Results: 51 patients reported a preoperative chronic pain condition, with 12 taking opioids preoperatively. 3 months after surgery 35% of patients reported having surgical site pain and 13.5% continued to use opioids for postsurgical pain relief. Postoperative opioid use was associated with interference with walking and work, and lower mood. Conclusion: Chronic postsurgical pain and ongoing opioid use are concerns that warrant the implementation of a Transitional Pain Service to modify the pain trajectories and enable effective opioid weaning following major surgery.

The incidence of chronic postsurgical pain (pain that persists for greater than 2 months and is a consequence of the surgical intervention) varies based on type of surgery, but can approach, and even, exceed 50%.

Chronic postsurgical pain (CPSP) places a significant burden on patient daily life and the healthcare system, and is often misidentified and poorly managed in the postdischarge period.

Opioid use is common in the CPSP patient population and is associated with significant risk for both morbidity and mortality.

In total, 35% of the present sample reported ongoing pain at their surgical incision site at 3 months after surgery.

A total of 13.5% reported ongoing opioid use for management of their surgical site pain at 3 months after surgery.

The majority of patients still using opioids for postsurgical pain at 3 months reported moderate-to-severe pain (Numeric Rating Scale ≥4).

Patients who were using opioids reported lower overall global health, and greater pain-related disability in daily life, including interference in walking and mood.

This study demonstrates the ongoing issues that CPSP presents, and highlights the need and importance of a Transitional Pain Service to identify at-risk patients and optimize pain management for them before, during and after discharge from hospital.

Our Transitional Pain Service is a multidisciplinary group consisting of pain physicians, nurse practitioners, psychologists, pharmacists and physiotherapists who provide regular support for patients while in hospital and as well as follow up in the postdischarge period to improve pain management, reduce persistent opioid use and lower the risk of developing of chronic postsurgical pain.

As many as 50% of surgical patients develop chronic postsurgical pain (CPSP) 1 year after surgery and a subset of these patients are at an increased risk for persistent opioid use [Citation1–4]. A universal definition of CPSP has not been agreed upon; however, a commonly accepted definition describes it as ‘pain that develops after surgical intervention and lasts for at least 2 months’ [Citation5]. There has been a 402% increase in opioid consumption from 1997 to 2007 in the USA, a significant proportion of which stems from treatment for chronic pain conditions [Citation6]. Opioid exposure after major surgery is often unavoidable. Unfortunately, the initiation of opioid medications for postoperative pain control often leads to their continued use for months and even years after hospital discharge. In Ontario, Canada, our data demonstrate that almost 50% of patients who undergo a major surgical procedure are discharged with an opioid prescription [Citation7]. Furthermore, 3.1% of postsurgical patients who had never taken opioids prior to hospital admission (i.e., opioid-naive) remained on an opioid medication 3 months after hospital discharge [Citation7]. This problem is not limited to major surgery: a retrospective analysis reported that opioid-naive patients who received a prescription for opioids within a week of low risk surgery had a 7.7% chance of continued opioid use 1 year later [Citation8]. Complicating the matter is the fact that general practitioners struggle with complex postsurgical pain patients as they transition from hospital to the community and frequently lack the expertise or level of comfort to wean their patients from opioids [Citation9]. Finally, there is a paucity of literature dealing with the management of postoperative pain as patients transition from the hospital setting to the community and even less research into the safe and effective weaning of patients from their postoperative opioid prescriptions.

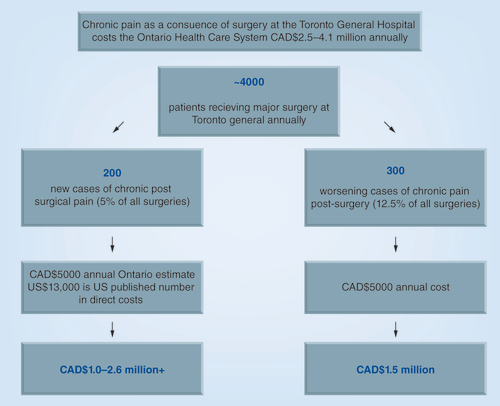

6000 surgeries are performed per year at the Toronto General Hospital, of which 4000 are major surgical operations. Using a conservative estimate of a 5% incidence of moderate to severe pain and an annual estimate based on data from the province of Ontario, Canada of CAD$5000 in direct heath-related costs, results in a CAD$1.0–2.6 million cost to the healthcare system. The 12.5% of patients who present to our pre-operative consult clinics with a pre-existing chronic pain condition and taking an opioid-based analgesic will leave on 100–300% more opioid medication than when they were admitted to hospital. Assuming a conservative increase in direct costs for 60% of patients (n = 300 vs 100% at n = 500) our data suggest the annual total cost for these patients would be CAD$1.5 million. The total estimated expenditure for all-cause chronic pain after major surgery is between CAD$2.5 and CAD$4.1 million from a single institution.

In most cases, patients will undergo surgery and return to baseline functional status after a few months, but reports have identified that some surgical populations have greater than a 50% risk of developing CPSP [Citation1,Citation10]. CPSP can persist beyond 1 year after surgery [Citation3,Citation11] and has significant impact on quality of life and patient well-being [Citation12–14]. Unfortunately, acute pain management after surgery is frequently suboptimal in hospital settings, and moderate-to-severe postoperative pain can limit postoperative rehabilitation and delay discharge from hospital [Citation15]. A subset of patients describe an increase in pain after hospital discharge [Citation16], and pain disability that ensues as a result of the development of CPSP has been estimated to incur annual direct and indirect costs of US$43,000 annually per patient [Citation13].

Most of the literature in this field deals with the incidence of, and risk factors for, CPSP after particular surgical interventions. There is little in the way of literature on the safe and effective management of postoperative pain as patients transition from the hospital, as well as follow-up and titration of their postdischarge opioids. We recently developed a Transitional Pain Service (TPS) at the Toronto General Hospital [Citation17,Citation18] which aims to modify the pain trajectories of patients who are at increased risk of developing CPSP and to reduce opioid consumption in the long term, which is often overlooked in the typical course of current perioperative care [Citation19]. The purpose of the present study was to determine the need for such a service at our institution prior to implementation of the TPS.

Methods

This was a single center needs assessment conducted by the Pain Research Unit at the Toronto General Hospital Department of Anesthesia and Pain Management that aimed to identify subgroups of surgical patients that warrant interventions to prevent progression to CPSP and prolonged postoperative opioid use. After REB approval and informed consent, researchers conducted brief 10–15-min interviews which included administration of the: Pain Disability Index (PDI), Brief Pain Inventory (Short Form; BPI), EQ-5D-5L Questionnaires and a 3-month follow-up pain questionnaire developed by the researchers. These interviews were conducted over a single telephone call, and all administered 3 months post-surgery. A 3-month follow-up period was selected to meet the commonly accepted time period to define CPSP (2 or more months postoperatively) and to be consistent with the standard reporting time point reflected in the literature of similar studies (3 months postoperatively).

A total of 200 patients were consecutively enrolled in this study using the Department of Anesthesia and Pain Management’s Acute Pain Service (APS) manager tracking system between September 2013 and April 2014. Patients eligible for the study: had undergone major surgery at Toronto General Hospital from the following surgical services: thoracic surgery, cardiac surgery, urological surgery, general surgery, gynecological surgery and otolaryngology; were cared for by the APS; and were discharged with an opioid-containing prescription. Patients were excluded if they could not speak English well enough to complete the interview and/or questionnaires. Additionally, patients were considered ineligible after a maximum of three unanswered telephone attempts. This study was approved by the Toronto General Hospital Research Ethics Board (REB# 13-6892-AE); there was no financial compensation for participants. Data were collected, maintained and analyzed by the Pain Research Unit at the Toronto General Hospital, Toronto, Canada.

The following data were collected: age, gender, OR date, type of surgery and the surgical service performing the operation. The primary end points were the incidence of postsurgical pain and incidence of persistent opioid use 3 months following surgery. Additionally, pain disability, quality of life measurements and overall patient satisfaction with their pain management while in hospital and after hospital discharge were evaluated through administration of questionnaires.

• Measurement tools

Pain Disability Index

The PDI assesses the extent to which persistent pain interferes with an individual’s ability to engage in seven different areas of everyday activity including: family/home responsibilities, recreation, social activity, occupation, sexual behavior, self-care and life-support activity. The PDI has good construct validity, test–retest reliability and internal consistency [Citation20,Citation21].

Brief Pain Inventory

The BPI asks patients to rate the severity of their pain and the degree to which their pain interferes with common aspects of psychosocial function [Citation22]. Initially developed to assess pain related to cancer, the BPI has been shown to be an appropriate measure for pain caused by a wide range of clinical conditions [Citation23].

EQ-5D-5L Health Questionnaire

The EQ-5D-5L questionnaire, an instrument commonly used to assess health outcomes. The difficulty scale assesses difficulties in various health-related areas (‘mobility,’ ‘self-care,’ ‘usual activities,’ ‘pain/discomfort’ and ‘anxiety/depression’), while the current health scale asks respondents to rate their current health from 0 to 100 [Citation24].

The Acute Pain Research Unit developed the Follow-up Pain Questionnaire (FUPQ) which assesses CPSP (intensity, duration), as well as medication use and satisfaction with hospital/home pain control. Patients were determined to have chronic postsurgical pain if they reported pain at the surgical incision site within the last week as per Question 2 on the Follow-Up Pain Questionnaire.

We identified patients taking opioids preoperatively based on their medication list obtained during their preoperative/preanesthetic assessment at our pre-admission clinic using our institution’s electronic medical record system in which all pre-operative medications are captured. We then identified continuing opioid users by asking patients to provide a list of medications for pain management during our 3-month telephone follow-up. ‘Continuing to use opioids’ refers specifically to patients who reported using opioids during their follow up interview at 3 months either for postsurgical pain, or other pain. However, we also established whether opioid use was for ongoing postsurgical pain, or for another pain condition. Opioid users were defined as those who reported taking opioids for pain management.

• Data analysis

Patients were dichotomized into two groups based on 3-month pain scores: those with and those without postoperative pain. Pain intensity scores, questionnaire scores and satisfaction ratings for the two groups are reported as mean ± standard deviation. Demographic variables, presence/absence of pain, and use/nonuse of opioids were compared between the two groups using Wilcoxon’s test for continuous (or ordinal) variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. One-way ANOVA’s were used to test differences in pain interference (on work, walking, and mood) between opioid users and nonusers at 3 months. A one-way ANOVA was performed to determine whether there was a significant effect of pain group (pain at 3 months vs no pain at 3 months) on health outcomes as measured by the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.2 (SAS Inc., NC, USA). All tests were two-sided and significance was defined as p < 0.01.

Results

• Demographics

Two hundred patients were enrolled in this study (98 males; 102 females; mean age = 58.7 years; standard deviation = 14.21). All participants had had major surgery at the Toronto General Hospital 3 months prior. Cardiac (31.5%), general (23.5%) and thoracic (20.5%) surgeries reflected the majority of the cohort (). A total of 51 patients (25.5% of cohort) reported having had a preoperative chronic pain condition. In total, 12 of the 51 patients (23.5%) who reported preoperative chronic pain also reported having used opioids prior to surgery.

• CPSP & persistent opioid use

Seventy patients (35%) reported postsurgical pain at the site of surgery/scar 3 months after surgery and 130 (65%) were pain free. A total of 27 participants (13.5%) reported ongoing opioid use for pain. Of these 27 patients, 19 (70.4%) reported using opioids for management of postsurgical pain. Nine of these 19 patients reported having used opioids preoperatively. Thus, 19 of the 70 patients (27.1%) with persistent postsurgical pain were using opioids 3 months after surgery. Patients who were using opioids at 3 months but who had been opioid-naive preoperatively (ten of the 19 patients) represented 14.3% of patients reporting CPSP. The remaining eight (29.6%) of the 27 patients were using opioids for pain unrelated to their surgery. Three of these patients reported preoperative opioid use. The majority of patients reported using codeine, morphine, oxycodone or hydromorphone for pain relief.

At 3 months’ time, 52.63% of patients still taking opioids for postsurgical pain reported moderate to severe pain (Numeric Rating Scale ≥4).

• Global health & pain disability/interference

Global health ratings (EQ-5D-5L) and PDI scores are shown in . For overall global health, non-opioid users (n = 173, mean = 71.27, standard deviation = 20.91) reported significantly higher scores (F = 13.93; p < 0.000) compared with opioid users (n = 27, mean = 55.33, standard deviation = 20.21) at 3 months postsurgery. Opioid users with postsurgical pain (n = 19) reported significantly greater pain-related interference in walking (F = 7.92; p < 0.01) and mood (F = 9.17; p < 0.01), and marginally greater interference in work (F = 5.47; p < 0.05), compared with nonopioid users with postsurgical pain (n = 51). There were no significant differences between groups in terms of pain disability in relation to enjoyment, relationships, activity or sleep.

Discussion

In this study, 35% of patients continued to have pain at their surgical incision site 3 months after surgery, therefore meeting the criteria for chronic postsurgical pain. The incidence determined in our sample is consistent with that previously documented in the literature [Citation1–4]. Of significant concern, is the fact that at 3 months after surgery, 27.1% of patients reporting pain remained on opioids to manage their persistent postsurgical pain. This is a distinctly greater incidence than previously published by our group (3.1%) [Citation7]. This difference may be related to differences in presurgical pain, diagnoses and medical complexity found in the present patient sample. We did not specifically look at the role of these factors in this study. Finally, pain scores were lower in the patients continuing to use opioids 3 months postsurgery, with 52.63% reporting pain scores ≥4, compared with 64.7% in the nonopioid using group.

Importantly, the results of the present study show that patients who continued to use opioids at 3 months post-surgery rated their overall global health to be lower compared with nonopioid users. Moreover, opioid users with ongoing postsurgical pain reported significantly more pain-related interference in relation to mobility, mood and ability to work compared with nonopioid users. This may reflect multifactorial influences, including more severe postoperative pain resulting in decreased functioning, as well as a direct effect from opioids themselves. Unfortunately, our study did not further explore this relationship. While the direct implications of pain interference from chronic postsurgical pain are unclear in the literature, it has been shown that chronic noncancer pain is associated with increased health care utilization [Citation25], increased workplace absenteeism [Citation26] and decreased workplace effectiveness [Citation27]. This equates to increased costs to both the healthcare system (), and the patient personally. Chronic postsurgical pain has been shown to incur personal costs of up to US$12,000 per year, and indirect costs, such as lost income, of US$30,000 per year [Citation13] and the incremental institutional costs that result from the development of CPSP are staggering.

Acute pain management strategies are typically limited to the immediate perioperative period with preventive, multimodal analgesic regimens and patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) [Citation28] being the main methods employed. The majority of postsurgical patients do not develop a significant acute pain problem or an exacerbation of a preexisting pain problem. We estimate that approximately 15% of complex postoperative pain patients develop moderate-to-severe CPSP, experience significant disability and continue to use opioids for pain relief in the long term. These patients will go on to consume 90% of Toronto General Hospital’s pain-related health care resources [Citation18]. outlines the annual projected total cost associated with patients that enter the Toronto General Hospital and go on to develop moderate-to-severe CPSP, pain disability and persistent opioid use. CPSP arising from our institution alone could cost the Canadian healthcare system CAD$2.5–4.1 million in annually. The public health burden, as well as the cost to the healthcare system from each patient who develops CPSP has made identification and treatment of these patients a priority. The above estimates are based on a recent publication that demonstrated the cost for a chronic patient in Ontario to be CAD$5177 annually [Citation29].

Unfortunately, opioid prescriptions occur as a reflex action for many physicians dealing with chronic pain patients, despite clear chronic neuropathic pain guidelines for prescription medications [Citation30]. Pain visits related to chronic noncancer pain increased by 11–14% between 2000 and 2007 and the cost of opioids for the management of chronic pain in the USA has grown to US$3.6 billion per year [Citation31]. This parallels a growth in the literature documenting the potential harm associated with prolonged opioid use. Traditionally, concerns about opioid use in the postoperative period involved side-effects such as nausea, vomiting, constipation, pruritus and respiratory depression. These typically present in the hospital during the immediate postoperative period [Citation15], and can be prevented with prophylactic strategies, or treated with various adjuncts. Often overlooked is the potential for opioid overdose when used in the chronic pain setting. It has been shown that long-term use of 50–99 mg of morphine equivalents per day is associated with a 3.7-fold increase in risk for overdose, which increases to 8.9-fold when doses exceed 100 mg of morphine per day [Citation32]. More recently, an association between opioid use and road trauma has been demonstrated. Compared with individuals consuming 20–49 mg of morphine per day, individuals using 100–199 mg of morphine per day had a twofold increase in odds for road trauma [Citation33]. Furthermore, opioid use has been linked to both overall increase in cardiovascular events [Citation34], and mortality [Citation34,Citation35]. The ongoing challenges with chronic postsurgical pain, as well as the growing body of knowledge concerning the risks and dangers of long-term opioid use, highlight the importance of identifying and intervening with patients at risk for the development of CPSP.

Results similar to those of the present study and years of research aimed at identifying risk factors for CPSP provided the impetus for the creation of The Toronto General Hospital TPS to address the needs of at-risk patients. The TPS is composed of a multidisciplinary team of chronic pain specialists, nurse practitioners, psychologists, physiotherapists (with acupuncture and myofascial release training) and patient care coordinators based on the identified needs from this study’s sample and our regional data [Citation7,Citation17]. The TPS is the first of its kind, and works independently, but in conjunction with, the Acute Pain Service and the surgical services at our hospital. The clinical algorithms used by the TPS are detailed elsewhere [Citation17]; however, the goal of the program is to provide regular, comprehensive and multidisciplinary care to patients identified at high risk for developing CPSP and long-term opioid use. The TPS places a special focus on safe, effective and monitored opioid weaning, as well as nonpharmacologic pain management strategies including physiotherapy, acupuncture and most importantly, psychotherapy. In its short time, the TPS has had several positive outcomes in the management of patients with complex postsurgical pain needs [Citation19,Citation36].

The present study has some important limitations. We did not specifically examine whether patients in our sample were being followed by a pain specialist or following a tailored pain management regimen/plan prior to enrolling in the study, or whether they had preoperative pain at the surgical site. Additionally, we did not report patient use of adjuncts such as gabapentinoids, NSAIDs, NMDA antagonists or epidural/regional techniques, as a focus of our study was to specifically evaluate postoperative opioid use after major surgery. We are aware, however, that these adjuncts are important in minimizing opioid use, and modifying the postoperative pain experience. Furthermore, we did not collect data on amount of opioid being consumed at 3 months after surgery, which limits our analysis.

Conclusion

In our cohort, 35% of patients presenting for major elective surgery reported ongoing CPSP at 3 months following the procedure. There was also a significant number of patients persisting on their opioid medications at 3 months. The persistent use of opioid medications was found to be associated with reduced function and low mood.

Future perspective

Tailored perioperative care for patients needs to be extended beyond the hospital setting. Our work continues to highlight the fact that a significant percentage of patients continue to struggle with persistent pain and opioid use following surgery. This is a discussion that needs to occur preoperatively and strategies to identify high-risk patients immediately postoperatively will help to decrease the burden to patients and the healthcare system by providing early and aggressive intervention with aim of modifying the postsurgical pain trajectory. As we await the development of novel therapeutics to treat chronic non cancer pain novel services such as the TPS will hopefully become an integral part of perioperative care and facilitate return to work for some patients as well as enabling patients to manage their pain and lead as meaningful of a life as possible while managing the pain disability that often ensues as a consequence of life saving surgery.

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

Table 2. Pain disability, pain interference, and global health ratings.

Ethical conduct of research

The authors state that they have obtained appropriate institutional review board approval or have followed the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for all human or animal experimental investigations. In addition, for investigations involving human subjects, informed consent has been obtained from the participants involved.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

H Clarke is supported by Merit Awards from the Department of Anaesthesia at the University of Toronto. H Clarke is also supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Fellowship. J Katz is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Canada Research Chair in Health Psychology at York University. MA Azam is supported by an Ontario Graduate Scholarship. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Searle R , SimpsonK . Chronic post-surgical pain . Contin. Educ. Anaesth. Crit. Care Pain10 ( 1 ), 12 – 14 ( 2010 ).

- Kehlet H , JensenTS , WoolfCJ . Persistent postsurgical pain: risk factors and prevention . Lancet367 ( 9522 ), 1618 – 1625 ( 2006 ).

- Katz J , SeltzerZ . Transition from acute to chronic postsurgical pain: risk factors and protective factors . Expert Rev. Neurother.9 ( 5 ), 723 – 744 ( 2009 ).

- Macrae WA . Chronic post-surgical pain: 10 years on . Br. J. Anaesth.101 ( 1 ), 77 – 86 ( 2008 ).

- Macrae WA , DaviesHT . Chronic postsurgical pain . In : Epidemiology of Pain.CrombieIKLintonSCroftPRet al.IASP Press , Seattle, WA, USA , 125 – 142 ( 1999 ).

- Manchikanti L , FellowsB , AilinaniH , PampatiV . Therapeutic use, abuse, and nonmedical use of opioids: a ten-year perspective . Pain Physician13 ( 5 ), 401 – 435 ( 2010 ).

- Clarke H , SonejiN , KoDT , YunL , WijeysunderaDN . Rates and risk factors for prolonged opioid use after major surgery: population based cohort study . BMJ348 , g1251 – g1251 ( 2014 ).

- Alam A , GomesT , ZhengH , MamdaniMM , JuurlinkDN , BellCM . Long-term analgesic use after low-risk surgery: a retrospective cohort study . Arch. Intern. Med.172 ( 5 ), 425 – 430 ( 2012 ).

- Robaux S , BouazizH , CornetC , BoivinJM , LefèvreN , LaxenaireMC . Acute postoperative pain management at home after ambulatory surgery: a French pilot survey of general practitioners’ views . Anesth. Analg.95 ( 5 ), 1258 – 1262 ( 2002 ).

- Haroutiunian S , NikolajsenL , FinnerupNB , JensenTS . The neuropathic component in persistent postsurgical pain: a systematic literature review . Pain154 ( 1 ), 95 – 102 ( 2013 ).

- Mongardon N , Pinton-GonnetC , SzekelyB , Michel-CherquiM , DreyfusJ-F , FischlerM . Assessment of chronic pain after thoracotomy: a 1-year prevalence study . Clin. J. Pain27 ( 8 ), 677 – 681 ( 2011 ).

- Kinney MAO , HootenWM , CassiviSDet al. Chronic postthoracotomy pain and health-related quality of life . Ann. Thorac. Surg.93 ( 4 ), 1242 – 1247 ( 2012 ).

- Parsons B , SchaeferC , MannRet al. Economic and humanistic burden of post-trauma and post-surgical neuropathic pain among adults in the United States . J. Pain Res.6 , 459 – 469 ( 2013 ).

- Buvanendran A . Chronic postsurgical pain . Anesth. Analg.115 ( 2 ), 231 – 232 ( 2012 ).

- Dolin SJ . Tolerability of acute postoperative pain management: nausea, vomiting, sedation, pruritis, and urinary retention. Evidence from published data . Br. J. Anaesth.95 ( 5 ), 584 – 591 ( 2005 ).

- Apfelbaum JL , ChenC , MehtaSS , GanATJ . Postoperative pain experience: results from a national survey suggest postoperative pain continues to be undermanaged . Anesth. Analg.97 ( 2 ), 534 – 540 ( 2003 ).

- Katz J , WeinribA , FashlerSet al. The Toronto General Hospital Transitional Pain Service: development and implementation of a multidisciplinary program to prevent chronic postsurgical pain . J. Pain Res.8 , 695 – 702 ( 2015 ).

- Clarke H . Transitional Pain Medicine: Novel pharmacological treatments for the management of moderate to severe postsurgical pain . Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol.9 ( 3 ), 345 – 349 ( 2015 ).

- Huang A , KatzJ , ClarkeH . Ensuring safe prescribing of controlled substances for pain following surgery by developing a transitional pain service . Pain5 ( 2 ), 97 – 105 ( 2015 ).

- Pollard CA . Preliminary validity study of the pain disability index . Percept. Mot. Skills59 ( 3 ), 974 – 974 ( 1984 ).

- Tait RC , PollardCA , MargolisRB , DuckroPN , KrauseSJ . The Pain Disability Index: psychometric and validity data . Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil.68 ( 7 ), 438 – 441 ( 1987 ).

- Tan G , JensenMP , ThornbyJI , ShantiBF . Validation of the brief pain inventory for chronic nonmalignant pain . J. Pain5 ( 2 ), 133 – 137 ( 2004 ).

- Karoly P , RuehlmanLS , AikenLS , ToddM , NewtonC . Evaluating chronic pain impact among patients in primary care: further validation of a brief assessment instrument . Pain Med.7 ( 4 ), 289 – 298 ( 2006 ).

- Herdman M , GudexC , LloydAet al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L) . Qual. Life Res.20 ( 10 ), 1727 – 1736 ( 2011 ).

- Blyth FM , MarchLM , BrnabicAJM , CousinsMJ . Chronic pain and frequent use of health care . Pain111 ( 1–2 ), 51 – 58 ( 2004 ).

- Blyth FM , MarchLM , NicholasMK , CousinsMJ . Chronic pain, work performance and litigation . Pain103 ( 1 ), 41 – 47 ( 2003 ).

- van Leeuwen MT , BlythFM , MarchLM , NicholasMK , CousinsMJ . Chronic pain and reduced work effectiveness: the hidden cost to Australian employers . Eur. J. Pain10 ( 2 ), 161 – 166 ( 2006 ).

- Walder B , SchaferM , HenziI , TramèrMR . Efficacy and safety of patient-controlled opioid analgesia for acute postoperative pain. A quantitative systematic review . Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand.45 ( 7 ), 795 – 804 ( 2001 ).

- Hogan M-E , TaddioA , KatzJ , ShahV , KrahnM . Incremental healthcare costs for chronic pain in Ontario, Canada – a population-based matched cohort study of adolescents and adults using administrative data . Pain doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000561 ( 2016 ) ( Epub ahead of print ).

- Moulin D , BoulangerA , ClarkAJet al. Pharmacological management of chronic neuropathic pain: revised consensus statement from the Canadian Pain Society . Pain Res. Manag.19 ( 6 ), 328 – 335 ( 2014 ).

- Rasu RS , VouthyK , CrowlANet al. Cost of pain medication to treat adult patients with nonmalignant chronic pain in the United States . J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm.20 ( 9 ), 921 – 928 ( 2014 ).

- Dunn KM , SaundersKW , RutterCMet al. Opioid prescriptions for chronic pain and overdose: a cohort study . Ann. Int. Med.152 ( 2 ), 85 – 92 ( 2010 ).

- Gomes T , RedelmeierDA , JuurlinkDN , DhallaIA , CamachoX , MamdaniMM . Opioid dose and risk of road trauma in Canada . JAMA Intern. Med.173 ( 3 ), 196 – 201 ( 2013 ).

- Solomon DH , RassenJA , GlynnRJet al. The comparative safety of opioids for nonmalignant pain in older adults . Arch. Intern. Med.170 ( 22 ), 1979 – 1986 ( 2010 ).

- Dhalla IA , MamdaniMM , SivilottiMLA , KoppA , QureshiO , JuurlinkDN . Prescribing of opioid analgesics and related mortality before and after the introduction of long-acting oxycodone . CMAJ181 ( 12 ), 891 – 896 ( 2009 ).

- Meng H , HanlonJG , KatznelsonR , GhanekarA , McGilvrayI , ClarkeH . The prescription of medical cannabis by a transitional pain service to wean a patient with complex pain from opioid use following liver transplantation: a case report . Can. J. Anaesth.63 ( 3 ), 307 – 310 ( 2015 ).