Abstract

Aim: Long-term safety and effectiveness of a once-daily, single-entity, extended-release formulation of hydrocodone bitartrate (HYD) for the treatment of moderate to severe noncancer and nonneuropathic pain among patients with and without concurrent depression/anxiety at baseline. Materials & methods:Post hoc analysis. Results: HYD demonstrated a safety profile consistent with μ-opioid agonists: Serious adverse events in 12% patients with depression/anxiety including four deaths; 6% without depression/anxiety including one death. All pain scores declined by ≥2 points and mean daily HYD dose remained stable in both subgroups. Conclusion: More serious adverse events occurred among patients with comorbid depression/anxiety at baseline than among those without. HYD provided stable and effective analgesia for 52 weeks among chronic pain patients with and without comorbid depression/anxiety at baseline.

Chronic pain, estimated to affect approximately 100 million adults in the USA [Citation1] has a well-established association with mental conditions such as depression and/or anxiety (depression/anxiety) [Citation2–7]. Patients with chronic low back pain (CLBP) have reported significantly higher incidences of depression/anxiety relative to individuals without CLBP [Citation8]. Similarly, a population-based US national survey revealed that among patients with chronic spinal pain, the odds ratios for major depression and anxiety disorders were 2.5 and 2.3, respectively, relative to those without these disorders, indicating that depression/anxiety frequently co-occur with chronic spinal pain [Citation9]. These findings are consistent with an earlier analysis reporting that the prevalence of depression was 20.2% among patients who had chronic arthritis pain compared with 9.3% for the general population [Citation10]. Anxiety disorders occurred in 35.1% of patients with arthritis-related pain relative to 18.1% of individuals in the general population [Citation10].

Although chronic pain and mental disorders exhibit a reciprocal relationship, the mechanisms underlying their concurrence remain unknown [Citation11,Citation12]. The existence of comorbid depression/anxiety is associated with greater pain severity, disability and poorer health-related quality of life in patients with chronic pain relative to those without these comorbidities [Citation6,Citation11,Citation13,Citation14]. In addition, chronic pain patients with depression incur higher medical costs than those without depression [Citation15]. Guidelines from the American Pain Society recommend chronic opioid therapy for selected and monitored individuals with chronic moderate or severe noncancer pain that adversely affects function or quality of life [Citation16]. Despite the prevalent use of opioids in patients with chronic pain and comorbid depression/anxiety, few studies have examined the effects of long-term opioid treatment in this subgroup of patients.

Recently, the US FDA warned that prescribing opioid analgesics, prescription opioid cough products and benzodiazepines together has been associated with adverse outcomes including overdose deaths [Citation17]. A review of data from 2004 to 2011 showed that the number of patients who were prescribed both an opioid analgesic and a benzodiazepine increased by 41% between 2002 and 2014, which translates to an increase of more than 2.5 million opioid analgesic patients receiving benzodiazepines. Recent clinical guidelines for primary care clinicians from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and existing labeling warnings regarding combined use also caution prescribers about co-prescribing opioids and respiratory depressants, such as benzodiazepines to avoid potential serious health outcomes [Citation18].

In a primary long-term open-label study, 922 patients received single-entity, extended-release (ER), once-daily tablet formulation of hydrocodone bitartrate (Hysingla®ER; HYD; Purdue Pharma LP, CT, USA) at doses ranging from 20 to 120 mg in patients with moderate to severe chronic noncancer and nonneuropathic pain [Citation19]. Treatment with HYD was associated with improvements in pain control and activities of daily living, which were maintained over 52 weeks [Citation19]. Most patients did not require dose adjustments, few discontinued therapy for lack of efficacy and no new or unexpected safety issues were identified with long-term use [Citation19]. Depression/anxiety were among the most frequently reported comorbid conditions in the clinical study population at baseline (reported in 30 and 25% of patients, respectively) [Citation19].

A previously published 6-factor post hoc analysis of this open-label study found that patients with chronic pain and comorbid depression who were treated with HYD experienced clinically meaningful improvements in pain intensity and health-related quality of life [Citation20]. However, no specific analysis exists on the impact of depression/anxiety on HYD for the treatment of chronic pain. The objective of this post hoc analysis was to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of HYD 20–120 mg once daily over 52 weeks, specifically in chronic pain patients with and without concomitant depression/anxiety at baseline.

Materials & methods

• Study design & treatment

This study was a post hoc exploratory analysis of the safety and effectiveness of once-daily HYD in treating chronic pain among patients with and without controlled, ongoing depression/anxiety at baseline. The data are from an open-label, multicenter study that evaluated the safety and effectiveness of HYD 20–120 mg among patients with moderate to severe chronic noncancer and nonneuropathic pain (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01400139) [Citation19]. The study protocol was approved by an institutional review board, and all patients provided written informed consent before undergoing any study procedures.

A comprehensive description of study procedures was previously published [Citation19]. The study included a screening period of up to 14 days, a dose titration period of up to 45 days, a 52-week maintenance period and an optional taper period of up to 14 days. Following screening, patients entered the dose titration period, during which they were converted to HYD 20–80 mg, equivalent to 50–75% of their incoming opioid dose. HYD dose was adjusted (up to 120 mg) until patients achieved a stable dose that provided adequate analgesia with acceptable tolerability for ≥7 days. Patients entered the maintenance period on the stabilized HYD dose. Dose adjustments were permitted as necessary during the maintenance period, after which patients could enter the optional taper period. Throughout the study, concomitant use of supplemental pain medication such as nonopioid analgesics, sedative hypnotics and immediate-release opioids, but not ER opioids, was permitted as deemed appropriate by the investigator.

• Patients

This study included patients (≥18 years of age) with moderate to severe chronic noncancer and nonneuropathic pain lasting several hours daily for ≥3 months prior to screening. Patients were considered opioid experienced if their daily incoming opioid dosage was ≥5 mg oxycodone equivalents during the 14 days prior to the screening visit. At screening, eligible patients had chronic pain that was either controlled by a stable analgesic regimen equivalent to 0–120 mg oxycodone with an ‘average pain over the last 14 days’ score ≤4; or uncontrolled by a stable analgesic regimen equivalent to 0–100 mg oxycodone with an ‘average pain over the last 14 days’ score ≥5.

Depression/anxiety were self-reported and no specific Major Depressive Disorder or Generalized Anxiety Disorder scales or tools were required for study entry or were assessed during the study. Patients with depression/anxiety were permitted in this study only if it was controlled, and control was determined by the investigator. Those receiving treatment for depression/anxiety were required to be on a stable medication regimen for ≥1 month prior to the screening visit.

Patients were excluded if they had uncontrolled depression/anxiety; uncontrolled gout, pseudogout, psoriatic arthritis, active Lyme disease, inflammatory arthritis, trochanteric bursitis or ischial tuberosity bursitis; impaired liver or kidney function; or a history of alcohol abuse and/or addiction to licit or illicit drugs. Pregnant or lactating women were not eligible for this study.

• Assessments

Safety was assessed by treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs), laboratory analyses, vital sign measurements, physical examinations and electrocardiogram measurements. No specific scales or tools were used to assess the progression of depression/anxiety during the study. Effectiveness measures included daily ‘average pain over the last 24 h’ scores and daily ‘pain right now’ scores recorded on an 11-point numeric rating scale (with 0 indicating no pain, and 10 indicating worst imaginable pain); Brief Pain Inventory – Short Form (BPI-SF) evaluating pain severity and pain interference on daily function; and Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire assessing patients’ experience with HYD relative to their prestudy analgesic regimen.

• Statistics

The safety population comprised all patients who received ≥1 HYD dose. Because an efficacy analysis was not the primary objective of this study, formal statistical hypothesis testing was not conducted on any efficacy variables. A formal comparison of the efficacy and safety data from the two groups (i.e., patients with and without depression/anxiety) was not performed. Efficacy data were summarized for patients in the safety population. For demographics, baseline characteristics and efficacy variables, descriptive statistics including mean, mean change from baseline and associated 95% confidence intervals were summarized as applicable. Categorical variables were summarized by the number and percentage of patients, where appropriate.

Results

• Patient characteristics

Among the 922 patients enrolled in the primary study [Citation19] 352 (38%) had active, controlled depression/anxiety at baseline (). The majority of patients with baseline depression/anxiety were female (67%) and aged <65 years (86%). The baseline characteristics of patients with and without depression/anxiety were generally similar. However, a higher proportion of patients with depression/anxiety were female (67 vs 51%), white (91 vs 78%) and opioid-experienced (78 vs 54%) compared with patients without baseline depression/anxiety. The proportion of African Americans was lower among those with baseline depression/anxiety than those without (9 vs 19%).

Table 1. Summary of demography and baseline characteristics of patients with and without active depression/anxiety

The most frequent pain etiologies were similar among patients with and without depression/anxiety: back pain (57 and 52%, respectively) and osteoarthritis (38 and 40%, respectively). Among patients with depression/anxiety, the other pain etiologies (>20%) were intervertebral disc degeneration (22%), muscle spasms (22%) and arthralgia (21%), while arthralgia was the only other pain etiology with an incidence >20% among patients without depression/anxiety (22%; ). Among patients with depression/anxiety, the most common (>20%) nonpain etiologies were hypertension (50%), insomnia (41%), gastroesophageal reflux disease (36%), hysterectomy (30%), constipation (23%), seasonal allergy (20%) and hypercholesterolemia (20%), whereas the most common (>20%) among patients without depression/anxiety were hypertension (41%), insomnia (41%), seasonal allergy (22%) and gastroesophageal reflux disease (21%).

Table 2. Summary of medical history terms occurring in ≥10% of patients prior to enrollment by preferred term.

Prior to the study, a higher proportion of patients with depression/anxiety used opioid medications compared with those without (81 vs 57%, respectively). The most frequently used opioid therapies prior to baseline were the same among patients with or without depression/anxiety: hydrocodone/acetaminophen (50 and 33%, respectively), tramadol (11 and 10%, respectively), oxycodone/acetaminophen (13 and 10%, respectively) and oxycodone (10 and 6%, respectively).

Patients with depression/anxiety had a higher mean (standard error [SE]) incoming daily opioid dose at screening (26.2 [1.5] mg oxycodone) compared with those without depression/anxiety (16.0 [1.0] mg oxycodone), and a higher proportion of patients with depression/anxiety used nonopioid analgesics (89%) compared with those without (78%). Regardless of subgroup, the most commonly used nonopioid analgesics were the same among patients with or without depression/anxiety: ibuprofen (22 and 32%, respectively), naproxen (13 and 20%, respectively), paracetamol (acetaminophen; 10 and 13%, respectively), cyclobenzaprine (12 and 6%, respectively) and carisoprodol (8 and 5%, respectively). Among patients with depression/anxiety, the most frequently used antidepressants and anxiolytics used to treat pain at baseline are listed in .

Table 3. Concomitant medications used to treat pain in ≥2% of patients with and without active depression/anxiety at baseline.

• Safety

Among patients with and without depression/anxiety, similar proportions completed the dose titration period (81 and 78%, respectively), similar proportions completed the maintenance period (55 and 57%, respectively) and similar proportions discontinued the study due to AEs (AEs; 22 vs 23%, respectively; ). Overall, more patients with depression/anxiety discontinued for lack of therapeutic effect compared with patients without (11 vs 4%).

Table 4. Summary of patient disposition and reasons for study discontinuation among patients with and without active depression/anxiety at baseline.

During the titration period, patients with and without depression/anxiety had similar mean durations of treatment (21 and 18 days, respectively). During the maintenance period, cumulative extent of exposure was somewhat lower among patients with depression/anxiety compared to those without (240 and 254 days, respectively).

Similar proportions of patients with and without depression/anxiety discontinued the study due to AEs during the dose titration period (9 and 10%, respectively) and maintenance period (14 and 15%, respectively). The most common AEs leading to treatment discontinuation during the overall treatment period were generally similar between subgroups, with the individual incidences all ≤5%: nausea (3%), somnolence (2%), vomiting (2%), dizziness (1%), headache (1%), lethargy (1%), rash (1%) and constipation (1%) for patients with depression/anxiety; and nausea (5%), constipation (3%), vomiting (3%), somnolence (3%), dizziness (2%), fatigue (1%), sedation (1%), decreased appetite (1%) and headache (1%) for patients without depression/anxiety.

In general, patients with and without depression/anxiety had similar incidences of opioid-related treatment-emergent AEs (58 and 61%, respectively), although patients without depression/anxiety had a somewhat higher incidence of gastrointestinal disorders (including nausea, constipation and vomiting) compared with patients with depression/anxiety (45 vs 33%) ().

Table 5. Opioid-related treatment-emergent adverse events in patients with depression/anxiety at baseline.

All serious AEs (SAEs) occurred in ≤1% of patients in each subgroup. More SAEs occurred in patients who had depression/anxiety (66 SAEs in 43 patients [12%]) compared with those without depression/anxiety (48 SAEs in 36 patients [6%]). SAEs occurring among patients with depression/anxiety included chest pain in three patients (1%), asthma in three patients (1%), pneumonia in two patients (1%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in two patients (1%), osteoarthritis in two patients (1%) and drug abuse in two patients (1%). In those without depression/anxiety, the most common SAEs were drug abuse occurring in three patients (1%), myocardial ischemia in two patients (<1%), chest pain in two patients (<1%), diverticulitis in two patients (<1%) and osteoarthritis in two patients (<1%).

Overall, five deaths occurred during this study, of which four occurred among patients with depression/anxiety. Of these, one death, due to accidental acute hydrocodone, citalopram and cyclobenzaprine overdose, was considered related to HYD. This patient’s death was confounded by other contributing factors such as pre-existing morbid obesity and a previous AE of dilated cardiomyopathy.

Among patients without depression/anxiety, one patient died due to metabolic acidosis and thrombocytopenic embolic purpura.

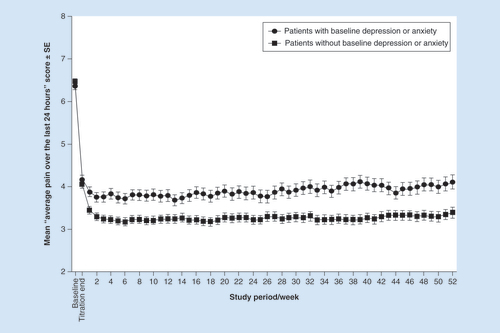

• Effectiveness

The trajectory of pain score reduction was similar between treatment groups. Among patients with and without depression/anxiety, mean (SE) ‘average pain over the last 24 h’ scores were: 6.4 (1.6) and 6.5 (1.6), respectively, at baseline (); 4.2 (0.1) and 4.1 (0.1), respectively, at the end of the dose titration period; and 4.1 (0.2) and 3.4 (0.1), respectively, at the end of the maintenance period (). Pain scores remained stable throughout the 52-week maintenance period, with mean scores of 4.0 (0.1) and 3.3 (0.1), respectively, for the overall maintenance period.

DT: Dose titration; HYD: Hydrocodone bitartrate; SE: Standard error.

At baseline, among patients with or without depression/anxiety, pain severity (SE), as evaluated by BPI-SF, was 6.0 (0.1) and 6.1 (0.1), respectively, while pain interference (SE) was 5.5 (0.1) and 4.8 (0.1), respectively (). For the overall maintenance period, the mean reductions in the BPI-SF for pain severity were 2.0 in patients with depression/anxiety and 2.7 in patients without depression/anxiety. Similarly, mean reductions in the pain interference subscale of the BPI-SF were 2.1 and 2.6 for patients with and without depression/anxiety, respectively.

Table 6. Brief pain inventory short form.

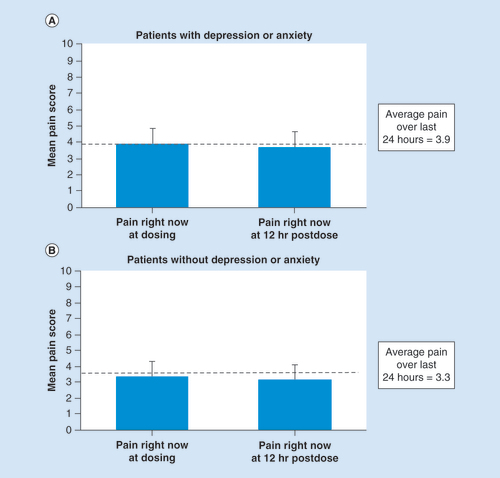

In both subgroups, mean ‘pain right now’ scores prior to dosing and at 12 h after dosing were comparable (). For patients with depression/anxiety, mean ‘pain right now’ (standard deviation) scores at dosing and at 12 h postdose were 3.9 (2.0) and 3.7 (2.0), respectively. In those without depression/anxiety, the corresponding scores were 3.3 (1.9) and 3.1 (1.9), respectively.

Error bars represent the standard deviation.

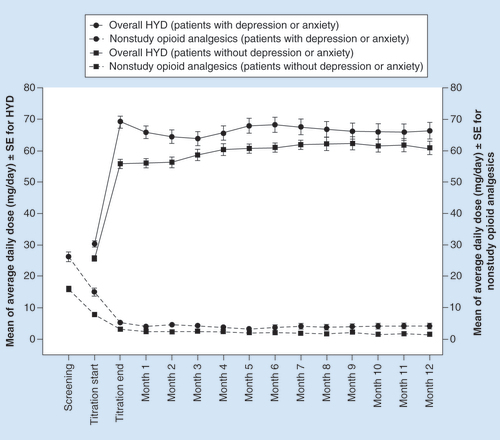

• HYD dose adjustments

The mean daily doses of HYD remained stable throughout the maintenance period for both subgroups of patients (). Among those with depression/anxiety, the mean (SE) daily HYD dose was 69.0 (1.9) mg at the end of titration and 66.4 (2.7) mg at the end of the maintenance period. For those without depression/anxiety, the mean daily dose of HYD was 55.8 (1.4) mg at the end of titration and 60.9 (2.1) mg at the end of the maintenance period.

HYD: Hydrocodone bitartrate; SE: Standard error.

At baseline, 55% of patients with depression/anxiety used nonstudy opioids compared with 33% of those without depression/anxiety. Within each subgroup, the use of nonstudy opioids decreased from baseline levels to the end of titration and remained relatively stable for the duration of the maintenance period (). Among those with depression/anxiety, the mean (SE) oxycodone-equivalent daily dose of nonstudy opioids decreased from 26.2 (1.5) mg at baseline to 5.3 (0.7) mg and 4.3 (0.8) mg at the end of the titration and the maintenance periods, respectively. In those without depression/anxiety, the mean (SE) oxycodone-equivalent daily dose of nonstudy opioids declined from 16.0 (1.0) mg at screening to 3.2 (0.5) mg and 1.5 (0.3) mg at the end of the dose titration and maintenance periods, respectively.

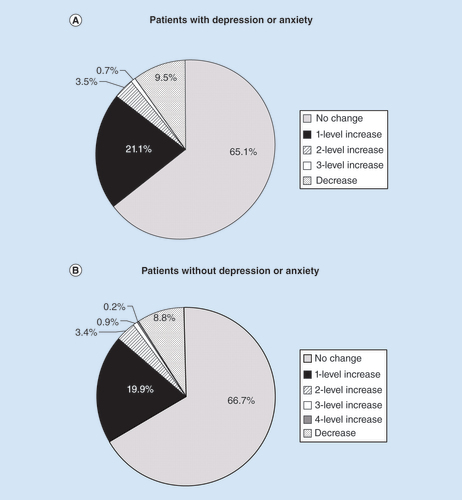

HYD dose adjustments were not necessary for the majority of patients during the maintenance period (). Among those with depression/anxiety, 65.1% of patients did not require a dosage change, 21.1% of patients required a 1-level dose increase and 9.5% of patients required a dose decrease; the corresponding percentages in patients without depression/anxiety were 66.7, 19.9 and 8.8%, respectively. A dose increase of 2 or more levels was required for 4.2% of patients with depression/anxiety and 4.5% of patients without depression/anxiety during the maintenance period. Overall, in both subgroups of patients, HYD dose adjustments demonstrated a similar pattern of distribution among those who completed 6 and 12 months of treatment during the maintenance period.

• Treatment satisfaction

A total of 267 of 285 patients with depression/anxiety and 427 of 443 patients without depression/anxiety who entered the maintenance period completed the Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire (). A large majority of patients within each group were satisfied with HYD (91 and 93%, respectively), with their pain management (88 and 93%, respectively) and with the frequency of HYD use (95 and 98%, respectively). Similarly, large majorities of patients with and without depression/anxiety (i.e., >95%) found it easy and convenient to use HYD. Regardless of depression/anxiety status, most patients (≥97%) also found it easy to plan HYD use. Qualitatively, there was little difference in satisfaction scores between the two groups. Satisfaction remained high for all dimensions in both groups.

Table 7. Treatment satisfaction questionnaire.

Discussion

In this post hoc analysis, we evaluated the safety and efficacy of once-daily HYD 20–120 mg over 52 weeks in patients with moderate to severe chronic noncancer and nonneuropathic pain in the presence or absence of depression/anxiety at baseline. Among patients with depression/anxiety, four deaths occurred. Only one death was considered related to HYD due to accidental overdose of hydrocodone, citalopram and cyclobenzaprine in a patient with complicated comorbidities. One death occurred among patients without depression/anxiety, which was considered to be not related to HYD.

Incidence of SAEs was twice as high among patients with depression/anxiety than among those without (12 vs 6%). Patients with and without depression/anxiety at baseline experienced clinically meaningful improvements in pain scores and pain function, as well as notable decreases in the use of nonstudy opioids; all were sustained throughout the 52-week maintenance period. Additionally, patients made few changes to their HYD dosages during the maintenance period.

A similar proportion of patients reporting opioid-related AEs in both subgroups. As is typical for μ-opioid agonists [Citation21,Citation22], nausea, constipation, vomiting, dizziness and somnolence were the most frequently observed opioid-related treatment-emergent AEs in this study. Numerically higher incidences of nausea, constipation and dizziness were observed among patients without baseline depression/anxiety, likely because fewer of these patients were opioid experienced at study entry than those with baseline depression/anxiety. Peripheral edema occurred numerically more frequently among patients with baseline depression/anxiety than in those without.

Overall, the findings of this analysis echo those of a previously published, 6-factor post hoc analysis of this same open-label study data, in which efficacy and safety among patients with and without depression (but not anxiety) were assessed [Citation20]. In the previous 6-factor post hoc analysis, all patients experienced clinically meaningful pain relief and rates of AEs were generally similar between those with and without depression. The incidence rate of SAEs was 12.7% among patients who did not have depression versus 9.2% among patient who did.In the present analysis, HYD treatment was discontinued by approximately 55% of patients in both subgroups, which is within the lower range (52–88%) reported for studies in which patients received at least 1 year of oral opioid therapy [Citation23,Citation24]. AEs were the most common reason for treatment discontinuation in this study, and the rates observed (≤22%) were slightly lower than those reported previously with long-term oral opioid therapy (22.9–32.5%) [Citation23,Citation24]. A previous analysis of a placebo-controlled study involving patients with CLBP demonstrated that patients with low or moderate levels of depression and anxiety were less likely to discontinue therapy due to adverse effects or lack of efficacy with ER hydromorphone during the titration phase (34.4 and 40.0% of patients, respectively) relative to patients with high levels of depression and anxiety (50.3%) [Citation25]. In our study, the rate of withdrawal due to AEs was similar in patients with and without depression/anxiety, irrespective of treatment phase (22 and 23%, respectively). More patients with depression/anxiety versus those without discontinued treatment due to lack of therapeutic effect during both dose titration (5 vs 2%, respectively) and maintenance phases (7 vs 3%, respectively). Discontinuation rates due to lack of therapeutic effect for the overall treatment period in patients with baseline depression/anxiety (11%) were consistent with previous observations in patients receiving long-term opioid therapy (10.3–11.9%) [Citation23,Citation24].

In our study, long-term HYD treatment was effective in patients with and without baseline depression/anxiety. Mean ‘average pain over the last 24 h’ scores declined during the titration period and remained stable throughout the maintenance period in both subgroups of patients. Relative to baseline levels, patients with and without baseline depression/anxiety achieved a mean reduction of 2.3 and 3.1 points in ‘average pain over the last 24 h’ scores at the end of the maintenance period, respectively, indicating that patients in both subgroups achieved clinically important analgesia with HYD treatment [Citation26]. Similarly, BPI-SF pain interference scores declined from baseline levels by 2.1 and 2.6 points during the overall maintenance period in patients with and without depression/anxiety, respectively, thereby demonstrating that 52 weeks of HYD treatment resulted in clinically meaningful functional improvements for patients, regardless of the presence of baseline depression/anxiety [Citation27]. Additionally, HYD provided consistent analgesia throughout the 24-h dosing interval as indicated by similar ‘pain right now’ scores at dosing and at 12 h postdose in both subgroups of patients.

In both subgroups of patients, the mean daily HYD doses remained stable throughout the 52-week maintenance period (range, 63.8–68.2 mg/day for patients with and 56.1–62.4 mg/day for patients without depression/anxiety). Furthermore, the mean daily dose of supplemental nonstudy opioids declined from baseline levels during the titration period, and this reduction was sustained for the duration of the maintenance period in patients with and without baseline depression/anxiety (range: 3.3–5.3 mg/day and 1.5–3.2 mg/day, respectively). A majority of patients, including similar proportions of patients with and without depression/anxiety, required no dose adjustment during the maintenance period, and fewer than 5% of patients required increases of two or more dose levels in either subgroup. Finally, patients with and without baseline depression/anxiety expressed a high degree of satisfaction with HYD as an analgesic, as well as with its ease and convenience of use. Collectively, these results suggest that, regardless of the baseline status of depression/anxiety, analgesia provided by HYD remains consistent over prolonged treatment durations.

Among chronic pain patients, the presence of depression/anxiety is generally associated with pain that is resistant to treatment. An analysis of a healthcare database suggested that patients with chronic pain and a recent history of depression were more likely to receive a higher average daily opioid dose and longer durations of opioid therapy than those without previous depression [Citation28]. Consistent with these findings, high levels of depression, anxiety or neuroticism were associated with decreased analgesia, as evaluated by percent total pain relief and percent summed pain intensity differences, among patients who received a single intravenous dose of morphine for chronic discogenic low back pain [Citation29]. In another 6.5-month study, patients with chronic back pain and high levels of depression, anxiety and pain catastrophizing were shown to have nearly 50% less improvement in pain following opioid therapy than those with low levels of these comorbidities [Citation30]. Similarly, among patients with chronic noncancer and nonneuropathic pain, those with a history of depression received a higher HYD dose at the end of titration period and at the end of the maintenance period [Citation20].

In the previously published 6-factor post hoc analysis study, although ‘average pain over the last 24 h’ scores at baseline were similar between patients with and without a history of depression, those with a history of depression reported greater pain interference and higher opioid use than those without a history of depression [Citation20]. Following treatment with HYD for 52 weeks, while patients in both subgroups exceeded the minimum clinically important difference for a reduction in average pain intensity, those without a history of depression reported a greater decline than their counterparts with a history of depression [Citation20]. Decreases in pain interference also exceeded the minimum clinically important difference in both subgroups of patients, and there were no differences in the magnitude of reduction in those with and without a history of depression [Citation20]. The previously published 6-factor post hoc analysis also suggested that among patients with and without a history of depression, the differences in average pain intensity following treatment with HYD may be explained by differences in opioid experience and baseline pain severity between the two subgroups [Citation20]. Taken together, these complementary findings indicate that although patients achieve clinically meaningful analgesia for sustained durations regardless of their depression/anxiety status, those without baseline depression/anxiety are inclined to achieve greater improvements in pain relief than those with depression/anxiety, consistent with previous reports [Citation20,Citation28–30].

The study design reflects clinical practice and allowed dose adjustments during both the titration and the maintenance periods. However, this study has limitations inherent to exploratory post hoc analyses. Patients included in this analysis were required to have well-controlled depression/anxiety at baseline; however, these diagnoses were self-reported, control was determined by investigator opinion and no formal instruments were administered to determine the severity of depression, either at baseline or during treatment. Although concomitant medications including antidepressants, anxiolytics and benzodiazepines were recorded at baseline and during treatment, an analysis of dose adjustments for these medications was not performed. As a result, it cannot be determined whether there were changes in the severity of depression/anxiety during the study that may be associated with improved pain control. Finally, a formal statistical comparison between patients with and without baseline depression/anxiety was not done, thereby limiting our conclusions. Additional studies will be needed to address the limitations of this analysis.

In conclusion, while HYD tolerability was good, there were more SAEs and deaths among patients with depression/anxiety in this post hoc subanalysis of HYD treatment. Practitioners should carefully evaluate treatment options and follow-up more closely with depression/anxiety patients for improved outcomes. HYD provided clinically meaningful and sustained analgesia in chronic pain patients, regardless of the presence of baseline depression/anxiety, without the need for substantial concomitant treatment or dose adjustments. Thus, HYD may be suitable for long-term therapy among select patients with moderate-to-severe chronic pain and controlled depression/anxiety, provided that close clinical assessment for safety are undertaken.

Burden of chronic pain patients with depression & anxiety

Comorbid depression and/or anxiety is frequently associated with chronic pain patients. These chronic pain patients with depression and anxiety experience greater pain severity, disability and poorer health-related quality of life compared with those chronic pain patients without these comorbidities.

Although long-term opioid therapy may be used to treat chronic pain patients with comorbid depression and/or anxiety, few clinical studies have evaluated long-term opioid therapy effects in this subpopulation.

Recent clinical guidelines for primary care clinicians from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and existing labeling warnings regarding combined use also caution prescribers about co-prescribing opioids and respiratory depressants, such as benzodiazepines to avoid potential serious health outcomes.

Results from a secondary subanalysis of a large Hysingla®ER (HYD) long-term clinical trial in chronic pain patients with depression &/or anxiety

In this secondary subanalysis of a large Hysingla®ER (HYD) long-term clinical trial, evaluating HYD for chronic pain, compared patients with depression/anxiety to those without, addresses an area of clinical significance.

HYD treated patients with and without depression/anxiety at baseline experienced.

Clinically meaningful improvements in pain scores and pain function.

Notable decreases in the use of nonstudy opioids.

These effects were sustained throughout the 52-week maintenance period.

Patients made minimal changes to their HYD dosages during the maintenance period.

The incidence of serious adverse events was twice as high among patients with depression/anxiety than among those without (12 vs 6%).

More patients with depression/anxiety versus those without discontinued treatment due to lack of therapeutic effect during both dose titration (5 vs 2%, respectively) and maintenance phases (7 vs 3%, respectively).

Patient treatment satisfaction scores similar regardless of depression/anxiety status

A large majority of patients within each group were satisfied with HYD (91 and 93%, respectively), with their pain management (88 and 93%, respectively) and with the frequency of HYD use (95 and 98%, respectively).

Regardless of depression/anxiety status most patients (>95%) found it easy and convenient to use HYD.

Qualitatively, satisfaction scores remained high for all categories in both groups.

Clinical practice recommendation for chronic pain patients with depression/anxiety

Patients with chronic pain and a history of depression are more likely to receive a higher average daily opioid dose and longer durations of opioid therapy than those without previous depression.

It is recommended that practitioners should carefully evaluate treatment options and follow-up more closely with depression/anxiety patients for improved outcomes with close clinical assessment for safety.

HYD provided clinically meaningful and sustained analgesia in chronic pain patients, regardless of the presence of baseline depression/anxiety, without the need for substantial concomitant treatment or dose adjustments.

Ethical conduct

The authors state that they have obtained appropriate Institutional Review Board approval or have followed the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for all human or animal experimental investigations. In addition, for investigations involving human subjects, informed consent has been obtained from the participants involved.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This study was sponsored and funded by Purdue Pharma, LP, Stamford, CT. E He and R Ripa are employees of Purdue Pharma LP, Stamford, CT. L Taber was an investigator for the study. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Medical writing and editorial support were provided by S Kongara, and funded by Purdue Pharma LP, Stamford, CT.

References

- IOM (Institute of Medicine) . Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research . The National Academies Press , Washington, DC, USA ( 2011 ).

- Gureje O , VonKM , SimonGEet al. Persistent pain and well-being: a World Health Organization study in primary care . JAMA280 ( 2 ), 147 – 151 ( 1998 ).

- Demyttenaere K , BruffaertsR , LeeSet al. Mental disorders among persons with chronic back or neck pain: results from the World Mental Health Surveys . Pain129 ( 3 ), 332 – 342 ( 2007 ).

- Gureje O , VonKM , KolaLet al. The relation between multiple pains and mental disorders: results from the World Mental Health Surveys . Pain135 ( 1–2 ), 82 – 91 ( 2008 ).

- Gerrits MM , vanOP , van MarwijkHWet al. Pain and the onset of depressive and anxiety disorders . Pain155 ( 1 ), 53 – 59 ( 2014 ).

- Arnow BA , HunkelerEM , BlaseyCMet al. Comorbid depression, chronic pain, and disability in primary care . Psychosom. Med.68 ( 2 ), 262 – 268 ( 2006 ).

- Dersh J , PolatinPB , GatchelRJ . Chronic pain and psychopathology: research findings and theoretical considerations . Psychosom. Med.64 ( 5 ), 773 – 786 ( 2002 ).

- Gore M , SadoskyA , StaceyBRet al. The burden of chronic low back pain: clinical comorbidities, treatment patterns, and health care costs in usual care settings . Spine (Phila. PA 1976)37 ( 11 ), E668 – 677 ( 2012 ).

- Von Korff M , CraneP , LaneMet al. Chronic spinal pain and physical-mental comorbidity in the United States: results from the national comorbidity survey replication . Pain113 ( 3 ), 331 – 339 ( 2005 ).

- McWilliams LA , CoxBJ , EnnsMW . Mood and anxiety disorders associated with chronic pain: an examination in a nationally representative sample . Pain106 ( 1–2 ), 127 – 133 ( 2003 ).

- Bair MJ , RobinsonRL , KatonWet al. Depression and pain comorbidity: a literature review . Arch. Intern. Med.163 ( 20 ), 2433 – 2445 ( 2003 ).

- Asmundson GJ , KatzJ . Understanding the co-occurrence of anxiety disorders and chronic pain: state-of-the-art . Depress. Anxiety26 ( 10 ), 888 – 901 ( 2009 ).

- Bair MJ , WuJ , DamushTMet al. Association of depression and anxiety alone and in combination with chronic musculoskeletal pain in primary care patients . Psychosom. Med.70 ( 8 ), 890 – 897 ( 2008 ).

- Kroenke K , OutcaltS , KrebsEet al. Association between anxiety, health-related quality of life and functional impairment in primary care patients with chronic pain . Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry35 ( 4 ), 359 – 365 ( 2013 ).

- Arnow BA , BlaseyCM , LeeJet al. Relationships among depression, chronic pain, chronic disabling pain, and medical costs . Psychiatr. Serv.60 ( 3 ), 344 – 350 ( 2009 ).

- Chou R , FanciulloGJ , FinePGet al. Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain . J. Pain10 ( 2 ), 113 – 130 ( 2009 ).

- US Food and Drug Administration . FDA requires strong warnings for opioid analgesics, prescription opioid cough products, and benzodiazepine labeling related to serious risks and death from combined use [FDA Web site] ( 2016 ). http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm518697.htm .

- Dowell D , HaegerichTM , ChouR . CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain – United States, 2016 . MMWR Recomm. Rep.65 ( 1 ), 1 – 49 ( 2016 ).

- Wen W , TaberL , LynchSYet al. 12-Month safety and effectiveness of once daily hydrocodone tablets formulated with abuse-deterrent properties in patients with moderate to severe chronic pain . J. Opioid Manag.11 ( 4 ), 339 – 356 ( 2015 ).

- Bartoli A , MichnaE , HeEet al. Pain intensity and interference with functioning and well-being in subgroups of patients with chronic pain treated with once daily hydrocodone tablets . J. Opioid Manag.11 ( 6 ), 519 – 533 ( 2015 ).

- Benyamin R , TrescotAM , DattaSet al. Opioid complications and side effects . Pain Physician11 ( 2 Suppl. ), S105 – S120 ( 2008 ).

- Furlan AD , SandovalJA , Mailis-GagnonAet al. Opioids for chronic noncancer pain: a meta-analysis of effectiveness and side effects . CMAJ174 ( 11 ), 1589 – 1594 ( 2006 ).

- Noble M , TreadwellJR , TregearSJet al. Long-term opioid management for chronic noncancer pain . Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.1 , CD006605 ( 2010 ).

- Noble M , TregearSJ , TreadwellJRet al. Long-term opioid therapy for chronic noncancer pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy and safety . J. Pain Symptom Manage.35 ( 2 ), 214 – 228 ( 2008 ).

- Jamison RN , EdwardsRR , LiuXet al. Relationship of negative affect and outcome of an opioid therapy trial among low back pain patients . Pain Pract.13 ( 3 ), 173 – 181 ( 2013 ).

- Farrar JT , YoungJPJr , LaMoreauxLet al. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale . Pain94 ( 2 ), 149 – 158 ( 2001 ).

- Dworkin RH , TurkDC , WyrwichKWet al. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations . J. Pain9 ( 2 ), 105 – 121 ( 2008 ).

- Braden JB , SullivanMD , RayGTet al. Trends in long-term opioid therapy for noncancer pain among persons with a history of depression . Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry31 ( 6 ), 564 – 570 ( 2009 ).

- Wasan AD , DavarG , JamisonR . The association between negative affect and opioid analgesia in patients with discogenic low back pain . Pain117 ( 3 ), 450 – 461 ( 2005 ).

- Wasan AD , MichnaE , EdwardsRRet al. Psychiatric comorbidity is associated prospectively with diminished opioid analgesia and increased opioid misuse in patients with chronic low back pain . Anesthesiology123 ( 4 ), 861 – 872 ( 2015 ).

- Yarlas A , MillerK , WenWet al. A subgroup analysis found no diminished response to buprenorphine transdermal system treatment for chronic low back pain patients classified with depression . Pain Pract.16 ( 4 ), 473 – 485 ( 2016 ).