Abstract

Aim: To evaluate the pooled safety of sufentanil sublingual tablets (SSTs) administered at 30-mcg dose equivalents over ≤72 h for moderate-to-severe acute pain management in medically supervised settings. Patients & methods: Safety data from SST 30 mcg Phase III studies were pooled with an additional patient subset from studies in which two SST 15 mcg were self-administered within 20–25 min (30-mcg dose-equivalent). Results: Analyses included 804 patients. Median (range) SST 30-mcg dosing over 24 h was 7.0 (1–15) tablets. Adverse events (AEs) were experienced by 60.5% (SST) and 61.4% (placebo) and treatment-related AEs by 43.8% (SST) and 33.5% (placebo; 10.3% difference; 95% CI: 2.0–18.6) of patients. No dose-dependent increase in oxygen desaturation was observed with SST. Conclusion: SST was well-tolerated, with most AEs considered mild or moderate in severity.

The sufentanil sublingual tablet (SST) offers an advantage over intravenous opioids with regard to its noninvasive route of administration.

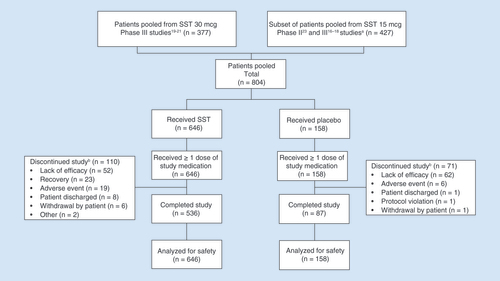

For the current analysis, safety data were pooled from the three Phase III studies of the SST 30 mcg in patients following surgery or in an emergency department. An additional subset of postoperative patients who self-administered SST 15 mcg in three Phase II and three Phase III studies were included in the pooled analysis if two SST 15-mcg doses were received within 20–25 min (30-mcg dose-equivalent).

Study drug exposure data, adverse events (AEs) and oxygen saturation data, as well as time to SST dissolution and morphine equivalence were analyzed.

A total of 804 patients were included in the safety analysis.

AEs were experienced by 60.5% (SST) and 61.4% (placebo) and treatment-related AEs were experienced by 43.8% (SST) and 33.5% (placebo) (10.3% difference; 95% CI: 2.0–18.6) of patients. Differences were significant for treatment-related AEs but not for AEs overall.

Across all studies, nausea, which occurred in 34.1% of patients receiving SST, was the only moderate AE that occurred in >5% of patients.

No dose-dependent increase in oxygen desaturation events was observed with SST.

Findings from the pooled analysis support that SST is well tolerated, with most AEs considered mild or moderate in severity, for the treatment of moderate-to-severe acute pain in medically supervised settings.

Despite advances in pain treatment, acute pain management remains inadequate and 20–40% of patients still experience severe pain following surgery [Citation1,Citation2]. Pain also remains the most common complaint of patients presenting to the emergency department. From 1996 to 2015 in the USA, annual visits to the emergency department increased from approximately 90 million [Citation3] to 137 million [Citation4], with nearly half of patients experiencing moderate (25%) or severe (20%) pain [Citation5]. Commonly an intravenous (IV) opioid, such as morphine or hydromorphone, is used to manage moderate-to-severe acute pain, which requires the time and cost of initiating IV access and can produce undesirable side effects such as nausea, vomiting and respiratory depression [Citation6]. The accumulation of the active metabolites of these opioids (i.e., morphine-3-glucuronide, morphine-6-glucuronide, hydromorphone-3-glucuronide and hydromorphone-6-glucuronide) can add to the risk of these events [Citation7].

Sufentanil, a synthetic opioid analgesic, is characterized by a high selectivity and affinity for mu-opioid receptors. As opposed to more commonly used opioids, including morphine and hydromorphone, sufentanil has no active metabolites. Sufentanil is 5–10 times more potent and twice as lipophilic as fentanyl [Citation8,Citation9], which allows for a small dosage form and rapid onset of analgesia when administered sublingually [Citation10]. Small clinical studies have also shown that sufentanil may produce less respiratory depressive effects relative to its analgesic effects than other opioids [Citation11–14]. Therefore, sublingual sufentanil may be a viable noninvasive alternative in treating moderate-to-severe acute pain.

The sufentanil sublingual tablet (SST 15 mcg; Zalviso®, Grünenthal GmbH, Aachen, Germany) was developed as a multiple-dose, patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) system for postoperative care. SST 15 mcg is intended for hospitalized patients who will likely require up to 72 h of acute pain management. Patients are able to self-administer SST 15 mcg as needed via a hand-held device secured to the bed, with a 20-min lockout period between doses. As it is administered sublingually, SST 15 mcg offers several advantages over IV administration, including an avoidance of IV-associated risks, greater patient mobility and a potential reduction in IV-related costs [Citation15]. Phase III studies of SST 15 mcg have demonstrated a favorable safety and tolerability profile, as well as efficacy in managing moderate-to-severe acute pain following major surgery compared with placebo [Citation16,Citation17] or IV morphine PCA [Citation18]. More recently, a higher strength (SST 30 mcg; DSUVIA™, AcelRx Pharmaceuticals, CA, USA; DZUVEO™, FGK Representative Service GmbH, Munich, Germany), single-dose, sublingual tablet housed in a prefilled applicator (not for use beyond 48 h [European Medicines Agency summary of product characteristics] or 72 h [US prescribing information]) was developed to address the unique needs of pain management in battlefield settings, following ambulatory surgery and in the emergency department where there is high patient turnover and availability of IV access may be limited. In clinical studies, SST 30 mcg provided a rapid onset of analgesia, with significant improvements in pain scores occurring within 15 min after administration [Citation19–21]. In each Phase III study, SST 30 mcg was well tolerated and adverse events (AEs) were generally considered mild, with no patients in the active treatment groups requiring naloxone.

Herein, we present a comprehensive safety analysis of data pooled from the Phase III SST 30 mcg studies supplemented with a selected pool of patients from the Phase II and Phase III SST 15 mcg studies, in which patients were treated with SST for ≤72 h.

Patients & methods

Study design

The pooled safety analysis included patients enrolled in the SST 30 mcg studies, as well as a select group of patients in SST 15 mcg studies (if they received a second dose of SST 15 mcg or placebo administered within 20–25 min after the first dose; Clinicaltrials.gov identifiers: NCT02356588, NCT02662556, NCT02447848, NCT00859313, NCT00612534, NCT00718081, NCT01539538, NCT01539642 and NCT01660763; ). The use of SST 15 mcg data was based on the establishment of bioequivalence of one SST 30-mcg tablet with two SST 15-mcg tablets dosed within 20 min of each other, as well as pharmacokinetic (PK) modeling, which concluded that this equivalence is expected if the dosing interval between two SST 15-mcg tablets is increased from 20 to 25 min [Citation22]. All patients in the SST 30 mcg and SST 15 mcg studies had moderate-to-severe pain (pain intensity ≥4 on an 11-point numeric rating scale, where 0 = no pain and 10 = the worst possible pain). Patients were excluded from the studies if they were opioid tolerant (defined as >15 mg of oral morphine sulfate-equivalent daily), were dependent on supplemental oxygen at home or had documented sleep apnea. In the postoperative studies, patients with intractable vomiting in the recovery room were also excluded. Prior to dosing, patients were additionally excluded if they had respiratory difficulties (respiratory rate of <8 or >24 breaths per min).

Table 1. Patient study pools for safety analysis.

The protocols for all clinical studies used to generate data for the current analysis were approved by the corresponding Institutional Review Board for each study site and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Studies of healthcare professional administration of SST 30 mcg

Data from SST 30 mcg studies were pooled from patients following abdominal surgery (placebo-controlled; study duration of 24 h with extension to 48 h if needed) [Citation19], postoperative patients from various surgeries including skeletal and soft-tissue, (single-arm; study duration of 12 h) [Citation20] and patients being treated for injury or trauma in emergency departments (single-arm; study duration up to 5 h) [Citation21] (see ).

In all SST 30 mcg studies, SST was administered by a healthcare professional via a single-dose applicator only upon patient request for pain relief, subject to a minimum 1-h redosing interval. Rescue analgesia for the postoperative studies was 1 mg IV morphine, no more frequently than hourly, as needed [Citation19,Citation20]. Patients in the emergency department study were provided rescue analgesia of either IV morphine (0.05 mg/kg) or oral oxycodone elixir (0.1 mg/kg), no more frequently than hourly, as needed [Citation21].

Studies of PCA with SST 15 mcg (30-mcg dose-equivalent)

Data from six SST 15 mcg studies in postoperative patients were included in the pooled analysis (see ), five of which were previously reported [Citation16–18,Citation23]. Study periods varied from 12 to 72 h. Four of the studies were double-blind, placebo-controlled studies [Citation16,Citation17,Citation23] and two were open-label studies including a comparison against IV morphine PCA [Citation18].

Safety analyses

Study drug exposure, patient discontinuations, AEs and oxygen desaturation events (all patients were continuously monitored with a pulse oximeter) were included in this analysis. All enrolled patients who received at least one dose of study drug were included in the analyses and summaries of safety data. Discontinuations and AEs were analyzed over the study treatment period (after the initial study drug dosing for both the SST 30 mcg and SST 15 mcg studies) and within 12 h after study drug discontinuation. To obtain an IV morphine equivalence for SST, drug utilization was compared in the IAP309 study in which patients received either SST 15 mcg or IV morphine.

Tablet erosion & bioadhesion

A reasonably rapid tablet erosion time is considered important for patient convenience (i.e., minimal interference with eating, drinking and talking), therefore erosion of the SST (data not previously reported) was monitored in a PK study [Citation26]. Specifically, subjects were asked every 2 min to open their mouths and raise their tongues so the clinician could observe the sublingual cavity and record their observations. The tablets were allowed to dissolve and were not crushed, chewed or swallowed, and subjects were requested to minimize talking for 10 min after the SST had been administered.

Statistical analysis (pooled data)

The baseline, dosing, termination and safety data included in this pooled analysis were summarized descriptively. For the analysis of termination data due to AEs and lack of efficacy, the difference in proportion and its 95% CI based on the normal distribution between SST and placebo treatments were calculated. For the analysis of AE data, the difference in proportion and its 95% CI based on the normal distribution between SST and placebo treatments, as well as between SST 15 mcg and SST 30 mcg treatments, were calculated. All data analyses were performed using SAS for Windows, Release 9.1.

Results

Baseline demographics & patient disposition

Overall, 804 patients were included in the pooled safety analysis. The most common (>1%) reasons for discontinuation were lack of efficacy (14.2%), AEs (3.1%), recovery (2.9%; a strong opioid was no longer indicated), patient discharged (1.1%) and withdrawal from the study by the patient (0.9%) (). Compared with patients receiving SST, a larger proportion of patients receiving placebo discontinued due to lack of efficacy (39.2% placebo vs 8.0% SST); however, the rates of discontinuation due to AEs were similar, albeit low (3.8% placebo vs 2.9% SST).

(A) Patients who received two doses of SST 15 mcg within 20–25 min (30-mcg dose-equivalent). (B) Prior to 24-h assessment.

SST: Sufentanil sublingual tablet.

Across all studies, the median (range) age was 56.0 (18.0–87.0) years and the majority of patients were female (60.9%), white (79.4%), had a BMI <30 (58.0%) and had undergone either abdominal (43.7%) or orthopedic (42.8%) surgery () [Citation16–21,Citation23]. Compared with patients who received SST 30 mcg, patients in the SST 15 mcg studies were older (64.0 vs 47.2 years) and had a higher BMI (30.3 vs 29.3 kg/m2). A greater percentage of patients who received SST 15 mcg had major orthopedic surgery compared with patients who received SST 30 mcg (76.5 vs 8.7%). Further, 23.5% of patients who received SST 30 mcg were nonsurgical trauma patients in the emergency department.

Table 2. Patient demographics and baseline characteristics in the sufentanil sublingual tablet clinical studies (pooled).

Study drug doses

Across the studies, SST 30 mcg was administered to 178 patients for ≥6 h, 93 patients for ≥12 h, 25 patients for ≥24 h and one patient for ≥48 h. SST 15 mcg was self-administered via the PCA system by 292 patients for ≥6 h, 255 patients for ≥12 h, 226 patients for ≥24 h and 101 patients for ≥48 h. The median (range) number of SST 30-mcg doses over the first 24 h in which patients remained in the study was 7.0 (1–15) tablets or 210 (30–450) mcg, while the median (range) number of SST 15-mcg doses over this same time period was 25.0 (2–55) tablets or 375 (30–825) mcg, which was understandably higher given the more extensive surgeries studied with this PCA system and the higher dosing available with the SST 15 mcg PCA system (up to 45 mcg/h).

Safety & AEs

All AEs

Overall, 60.7% of patients experienced at least one AE. The most common AEs experienced by ≥5% of all patients were nausea (35.3%), headache (9.7%), pyrexia (8.6%), vomiting (7.3%) and anemia (4.5%). AEs were experienced by 60.5 and 61.4% of patients receiving any SST dose and placebo, respectively (-0.9% difference [95% CI: -9.4–7.6]) () [Citation16–21,Citation23].

Table 3. Adverse events in the sufentanil sublingual tablet clinical studies (pooled): all adverse events and adverse events related† to study treatment.

Most of the AEs were rated as mild in severity by the clinical investigators. Nausea was the only moderate-rated AE that occurred in >5% of all patients, including in 9.0% receiving SST 30 mcg, 25.1% receiving SST 15 mcg, 17.0% receiving any SST dose and 17.1% receiving placebo. Combining all studies, 15 of the 804 patients experienced a severe AE. Eight patients who received SST 30 mcg experienced severe AEs of nausea (n = 4), headache (n = 2), procedural nausea (n = 2), procedural vomiting (n = 2), confusional state (n = 1), dizziness (n = 1), dry mouth (n = 1), euphoric mood (n = 1) and vomiting (n = 1). Four patients who received SST 15 mcg experienced severe AEs of oxygen saturation decreased (n = 2), hepatic enzyme increased (n = 1), nausea (n = 1) and postoperative ileus (n = 1). Three patients who received placebo experienced severe AEs of procedural nausea (n = 1), hemiparesis (n = 1) and abdominal pain (n = 1).

In all, nine serious AEs were experienced by a total of seven (0.9%) patients receiving SST 15 mcg (four patients), placebo (two patients) or SST 30 mcg (one patient) ().

Table 4. Serious adverse events.

There were no deaths in studies of SST 30 mcg. In studies of SST 15 mcg, there were two deaths, both of which occurred at least 18 days after discontinuation of study drug and were considered unrelated to treatment by the study investigator. One death was due to acute renal failure in a patient 30 days following discontinuation of SST 15 mcg. The other death was due to severe sepsis and occurred in a patient treated with IV morphine PCA in the active comparator study (because this patient received morphine and not SST, this patient was not included in the pooled safety analysis).

Treatment-related AEs

For all studies combined, 41.8% of patients experienced at least one AE considered related to treatment. Treatment-related AEs experienced by ≥5% of all patients were nausea (27.2%), vomiting (6.0%) and headache (5.2%). Overall, 283 (43.8%) patients who received any dose of SST experienced an AE related to treatment compared with 53 (33.5%) patients who received placebo (10.3% difference [95% CI: 2.0–18.6]) () [Citation16–21,Citation23].

AEs of special interest: respiratory & neuropsychiatric AEs

Most respiratory and neuropsychiatric AEs observed in the SST and placebo groups were mild to moderate and no opioid reversal agent (e.g., naloxone) was required for any patient receiving SST 30 mcg, while three patients who received SST 15 mg required naloxone, including the patient with the serious AE of oxygen saturation decreased in the Phase III orthopedic study [Citation16] (see ). One additional patient had a serious respiratory AE of hypoxia but did not require naloxone (this patient had a pulmonary embolism causing the event; ). Overall, 10/646 (1.5%) patients treated with SST discontinued a study due to a respiratory AE, which included six patients with oxygen desaturation (including the patient with the serious AE) and one patient each with bradypnea, hypoventilation, hypoxia and respiratory rate increased.

Three (0.5%) patients receiving SST experienced neuropsychiatric events considered severe and related to study treatment, including dizziness, headache and confusional state (n = 1), euphoric mood (n = 1) and headache (n = 1). Twelve (1.9%) patients receiving SST discontinued due to a neuropsychiatric event, including sedation (n = 4), agitation (n = 2), anxiety (n = 2) confusional state (n = 2) and dizziness (n = 2). One patient experienced a serious AE of confusional state following a pulmonary embolism ().

Vital signs & clinical laboratory results

Across the studies, mean changes from baseline in respiration rate were generally small and not clinically meaningful. No dose-dependent increase in percent of patients with an oxygen desaturation event was observed with SST, determined by comparing the total 24-h SST dose exposure (<300 vs ≥300 mcg) in studies of at least 24 h in duration () [Citation16,Citation17,Citation19,Citation23].

Table 5. Higher versus lower 24-h dosing of sufentanil sublingual tablet in Phase III studies ≥24 h: lowest oxygen saturation by treatment and dose group.

Median drug utilization: morphine equivalent per SST dose based on duration of exposure

The morphine equivalent per SST dosage strength was determined utilizing dosing data from 357 patients in the active-comparator study [Citation18] (SST 15 mcg [n = 177] vs IV morphine PCA [n = 180]) (). Within the first 5 h after initiation of the first dose of treatment with SST 15 mcg PCA or IV morphine PCA (the time during which active morphine metabolites will not yet have accumulated and exerted analgesic effects) [Citation27], SST 15 mcg was calculated to be equal to approximately 2.5 mg IV morphine based on drug utilization in each treatment group over this 5-h period (or 5 mg IV morphine for 30-mcg SST).

Table 6. Median drug utilization: morphine equivalent per sufentanil sublingual tablet dose based on duration of exposure.

Time to dissolution of SST

In the SST 15 mcg PK study [Citation26] where time of tablet erosion was monitored, the tablet began to dissolve immediately once it was placed under the tongue and the mean and median erosion times for sublingual placement of the SST were 6.2 and 5 min (range 4–16), respectively, with little movement in the tablet location. It should be noted that approximately 22% of the SST formulation is water-insoluble, non-nutritive excipients (i.e., dicalcium phosphate anhydrous, stearic acid and magnesium stearate), which do not fully dissolve in water or saliva and must be ultimately washed away by swallowing. Sufentanil absorption by subjects with very fast or slow times of erosion were not dissimilar (data not shown), suggesting that erosion time does not have a substantial influence on efficacy or safety.

Discussion

Pooled results from ten clinical trials, in which patients were treated with SST 30 and 15 mcg for ≤72 h, indicate that SST has a tolerable safety profile, with most AEs considered mild or moderate in severity. As expected, a significantly greater proportion of patients in the SST group compared with the placebo group experienced ≥1 treatment-related AE; this difference was not significant when considering AEs overall. The pooled safety population included SST 15-mcg exposure considered equivalent to or higher than SST 30 mcg (two SST 15-mcg tablets dosed within 20–25 min of each other, with a third dose often occurring within the hour). Overall, safety assessments indicate that AEs are similar to those observed with other opioids in postoperative studies [Citation6,Citation18] and no dose-dependent increases in oxygen desaturation events were observed with SST. Most of the respiratory events observed with SST were mild to moderate and self-limited, and naloxone was not required for any patient receiving SST 30 mcg and required by three patients receiving SST 15 mcg. Of note, two additional patients in the placebo arms required naloxone.

IV morphine is commonly used in the management of moderate-to-severe acute pain in a hospital setting. However, morphine has been associated with cognitive adverse effects including impaired recall, delayed reaction time and impaired memory [Citation28–30]. In contrast, the study of patients in the emergency department showed no evidence of cognitive impairment following treatment with SST 30 mcg [Citation21]. In that study, 75 patients were evaluated predose and postdose on the six-item screener to identify cognitive impairment and most patients (97.3%) had the same or improved score following SST 30-mcg treatment. Furthermore, the active-comparator study showed a lower rate of oxygen desaturation events over the 72-h study period for patients who received SST 15 mcg PCA compared with patients receiving IV morphine PCA [Citation18]. In that same study, no significant differences in overall AEs were observed between treatment arms.

In addition to a potentially improved tolerability profile, SST also offers a distinct advantage over IV morphine with regard to route of administration, as patients generally prefer oral administration of medication over IV or intramuscular administration [Citation31–33]. However, swallowed oral opioid tablets are typically limited by slow onset of action [Citation34]. Sufentanil has a rapid penetration of the blood–brain barrier compared with hydromorphone and morphine, as reflected by the equilibration half-life between plasma and the CNS (6, 46 and 168 min, respectively) [Citation8,Citation27,Citation35]. Clinical trials have demonstrated significant reductions in pain intensity occurring within 15–30 min of SST administration [Citation16,Citation17,Citation19–21,Citation36]. In the active-comparator SST 15 mcg study, patients reported improved pain control with SST 15-mcg PCA compared with IV morphine PCA following major orthopedic or open abdominal surgery [Citation18]. In this study, clinically meaningful analgesia (defined as a pain intensity difference from baseline of 1.3 for acute pain [Citation37]) was observed after 1.3 h in the SST 15-mcg PCA group compared with 7 h in the IV morphine PCA group. In this study, a SST 15-mcg dose was initially equivalent to 2.5 mg of IV morphine when use was averaged over the first 5 h, but dropped to an equivalent of 1.8 mg of IV morphine over 48 h. This apparent lowering of SST potency over time compared with morphine is likely due to active morphine metabolite accumulation. Patients with normal renal function after 48 h of exposure to IV morphine PCA had an average morphine-6-glucuronide plasma concentration of 20 ng/m, similar to their average morphine sulfate concentration of 22 ng/ml [Citation18].

Limitations

Not all studies of SST were placebo-controlled and no study of SST 30 mcg included an active comparator, which may limit the ability to interpret these results. This pooled analysis also included patients in SST 15 mcg PCA studies who received two doses of SST 15 mcg within the first 25 min of the study. Furthermore, 75% of these patients also received a third dose of SST 15 mcg in the first hour of treatment, exceeding by 50% the dose of sufentanil received from a single SST 30-mcg dose given per hour. Overall, the 24-h median (range) SST dose amount utilized was 1.8-times higher for the SST 15-mcg (375 mcg) group compared with the SST 30-mcg (210 mcg) group. The increased rate of AEs for these SST 15-mcg patients (compared with the SST 30-mcg groups) is likely due to this higher exposure as well as demographic factors, such as, increased age and higher BMIs. Further, it should also be noted that patients in the SST 15 mcg PCA studies had undergone longer, more complicated surgeries (knee/hip replacement or open abdominal surgery), with the expectation of requiring 2–3 days of acute pain management within a hospital setting. In contrast, the majority of patients in the SST 30 mcg studies were outpatient or short-stay (primarily laparoscopic) surgery and often discharged home at 12–24 h postoperatively. Last, long-term consequences of opioid treatment, such as tolerance or addiction, were not identified in these short-term studies; however, the labeled use of SST is for no more than 2–3 days duration in medically supervised and monitored settings.

Conclusion

While a significantly greater proportion of patients in the SST group compared with the placebo group experienced ≥1 treatment-related AE, the overall findings from the pooled analysis support that short-term (≤72 h) administration of SST is well tolerated–with most AEs considered mild or moderate in severity–for the treatment of moderate-to-severe acute pain in medically supervised settings.

Author contributions

All the authors analyzed and interpreted the data, drafted or revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and provided approval of the final version. Y-K Chiang was involved in the study design and carried out data analyses of the original studies included in this analysis. PP Palmer and KP DiDonato were involved in data acquisition and PP Palmer was also involved in study concept and design.

Ethical conduct of research

The protocols for all clinical studies used to generate data for the current analysis were approved by the corresponding Institutional Review Board for each study site and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The SST 30 mcg studies were funded by AcelRx Pharmaceuticals and were funded in part by the Clinical and Rehabilitative Medicine Research Program (CRMRP) of the US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command (USAMRMC) under contract no. W81XWH-15-C-0046 and no. W81XWH-11-1-0361. JR Miner and D Leiman are consultants to AcelRx. JR Miner, TI Melson and D Leiman received research funding from AcelRx. HS Minkowitz is a consultant for and has received research support from AcelRx, Trevana, Heron, Durect, Acacia, Avenue, Recro and Innocoll, and has also received research support from Sorrento, Semnur, Merck, SPR, Pfizer, and Sollis. YK Chiang is a paid statistical consultant for AcelRx. KP DiDonato and PP Palmer are employees and have stock ownership of AcelRx. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Writing and editorial assistance were provided by R Steger and P Baron (BlueMomentum, an Ashfield Company, part of UDG Healthcare plc) and funded by AcelRx Pharmaceuticals.

Data sharing statement

The authors certify that this manuscript reports the secondary analysis of clinical trial data that have been shared with them, and that the use of this shared data is in accordance with the terms (if any) agreed upon their receipt. The source of this data is: Clinicaltrials.gov identifiers: NCT02356588, NCT02662556, NCT02447848, NCT00859313, NCT00612534, NCT00718081, NCT01539538, NCT01539642 and NCT01660763.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Sommer M , De RijkeJM , Van KleefMet al. The prevalence of postoperative pain in a sample of 1490 surgical inpatients . Eur. J. Anaesthesiol.25 ( 4 ), 267 – 274 ( 2008 ).

- Gerbershagen HJ , AduckathilS , van WijckAJ , PeelenLM , KalkmanCJ , MeissnerW . Pain intensity on the first day after surgery: a prospective cohort study comparing 179 surgical procedures . Anesthesiology118 ( 4 ), 934 – 944 ( 2013 ).

- McCaig LF , StussmanBJ . National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 1996 emergency department summary . National Center for Health Statistics ( 1997 ). www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad293.pdf .

- Centers for Disease Control (CDC) . Emergency department visits ( 2015 ). www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/emergency-department.htm .

- Pitts S , NiskaRW , XuJ , BurtC . National hospital ambulatory medical care survey: 2006 emergency department summary . National Center for Health Statistics ( 2008 ). www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr007.pdf .

- Hutchison RW , ChonEH , TuckerWFet al. A comparison of a fentanyl, morphine, and hydromorphone patient-controlled intravenous delivery for acute postoperative analgesia: a multicenter study of opioid-induced adverse reactions . Hosp. Pharm.41 ( 7 ), 659 – 663 ( 2006 ).

- Smith H . The metabolism of opioid agents and the clinical impact of their active metabolites . Clin. J. Pain.27 ( 9 ), 824 – 838 ( 2011 ).

- Scott JC , CookeJE , StanskiDR . Electroencephalographic quantitation of opioid effect: comparative pharmacodynamics of fentanyl and sufentanil . Anesthesiology74 ( 1 ), 34 – 42 ( 1991 ).

- Lehmann KA , GerhardA , Horrichs-HaermeyerG , GrondS , ZechD . Postoperative patient-controlled analgesia with sufentanil: analgesic efficacy and minimum effective concentrations . Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand.35 , 221 – 226 ( 1991 ).

- Gardner-Nix J . Oral transmucosal fentanyl and sufentanil for incident pain . J. Pain Sympt. Manag.22 ( 2 ), 627 – 630 ( 2001 ).

- Clark N , MeulemanT , LiuW , ZwanikkenP , PaceN , StanleyT . Comparison of sufentanil-N2O and fentanyl-N2O in patients without cardiac disease undergoing general surgery . Anesthesiology66 ( 2 ), 130 – 135 ( 1987 ).

- Ved SA , DuboisM , CarronH , LeaD . Sufentanil and alfentanil pattern of consumption during patient-controlled analgesia: a comparison with morphine . Clin. J. Pain.5 ( Suppl. 1 ), S63 – S70 ( 1989 ).

- Bailey PL , StreisandJB , EastKAet al. Differences in magnitude and duration of opioid-induced respiratory depression and analgesia with fentanyl and sufentanil . Anesth. Analg.70 ( 1 ), 8 – 15 ( 1990 ).

- Conti G , ArcangeliA , AntonelliMet al. Sedation with sufentanil in patients receiving pressure support ventilation has no effects on respiration: a pilot study . Can. J. Anesth.51 ( 5 ), 494 – 499 ( 2004 ).

- Golembiewski J , DastaJ , PalmerPP . Evolution of patient-controlled analgesia: from intravenous to sublingual treatment . Hosp. Pharm.51 ( 3 ), 214 – 229 ( 2016 ).

- Jove M , GriffinDW , MinkowitzHS , Ben-DavidB , EvashenkMA , PalmerPP . Sufentanil sublingual tablet system for the management of postoperative pain after knee or hip arthroplasty: a randomized, placebo-controlled study . Anesthesiology123 ( 2 ), 434 – 443 ( 2015 ).

- Ringold FG , MinkowitzHS , GanTJet al. Sufentanil sublingual tablet system for the management of postoperative pain following open abdominal surgery: a randomized, placebo-controlled study . Regional Anesth. Pain Med.40 ( 1 ), 22 – 30 ( 2015 ).

- Melson TI , BoyerDL , MinkowitzHSet al. Sufentanil sublingual tablet system vs. intravenous patient-controlled analgesia with morphine for postoperative pain control: a randomized, active-comparator trial . Pain Pract.14 ( 8 ), 679 – 688 ( 2014 ).

- Minkowitz HS , LeimanD , MelsonT , SinglaN , DiDonatoKP , PalmerPP . Sufentanil sublingual tablet 30 mcg for the management of pain following abdominal surgery: a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase-3 study . Pain Pract.17 ( 7 ), 848 – 858 ( 2017 ).

- Hutchins JL , LeimanD , MinkowitzHS , JoveM , DiDonatoKP , PalmerPP . An open-label study of sufentanil sublingual tablet 30mcg in patients with postoperative pain . Pain Med.19 ( 10 ), 2058 – 2068 ( 2018 ).

- Miner JR , RafiqueZ , MinkowitzHS , DiDonatoKP , PalmerPP . Sufentanil sublingual tablet 30 mcg for moderate-to-severe acute pain in the emergency department . Am. J. Emerg. Med.36 ( 6 ), 954 – 961 ( 2018 ).

- Fisher DM , ChangP , WadaDR , DahanA , PalmerPP . Pharmacokinetic properties of a sufentanil sublingual tablet intended to treat acute pain . Anesthesiology128 ( 5 ), 943 – 952 ( 2018 ).

- Minkowitz HS , SinglaNK , EvashenkMAet al. Pharmacokinetics of sublingual sufentanil tablets and efficacy and safety in the management of postoperative pain . Regional Anesth. Pain Med.38 ( 2 ), 131 – 139 ( 2013 ).

- Boonstra AM , StewartRE , KökeAJet al. Cut-off points for mild, moderate, and severe pain on the numeric rating scale for pain in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: variability and influence of sex and catastrophizing . Front. Psychol.7 ( 1466 ), 1 – 9 , [ eCollection 2016 ] ( 2016 ).

- Krebs EE , CareyTS , WeinbergerM . Accuracy of the pain numeric rating scale as a screening test in primary care . J. Gen. Intern. Med.22 , 1453 – 1458 ( 2007 ).

- Willsie SK , EvashenkMA , HamelLG , HwangSS , ChiangYK , PalmerPP . Pharmacokinetic properties of single- and repeated-dose sufentanil sublingual tablets in healthy volunteers . Clin. Ther.37 , 145 – 155 ( 2015 ).

- Lötsch J , SkarkeC , SchmidtH , GroschS , GeisslingerG . The transfer half-life of morphine-6-glucuronide from plasma to effect site assessed by pupil size measurements in healthy volunteers . Anesthesiology95 , 1329 – 1338 ( 2001 ).

- Zacny JP , LichtorJL , FlemmingD , CoalsonDW , ThompsonWK . A dose-response analysis of the subjective, psychomotor and physiological effects of intravenous morphine in healthy volunteers . J. Pharmacol. Exper. Ther.268 ( 1 ), 1 – 9 ( 1994 ).

- Kerr B , HillH , CodaBet al. Concentration-related effects of morphine on cognition and motor control in human subjects . Neuropsychopharmacology5 ( 3 ), 157 – 166 ( 1991 ).

- Kamboj SK , TookmanA , JonesL , CurranHV . The effects of immediate-release morphine on cognitive functioning in patients receiving chronic opioid therapy in palliative care . Pain117 ( 3 ), 388 – 395 ( 2005 ).

- Alten R , KrügerK , RelleckeJet al. Examining patient preferences in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis using a discrete-choice approach . Patient Prefer. Adherence10 , 2217 – 2228 ( 2016 ).

- Eek D , KroheM , MazarIet al. Patient-reported preferences for oral versus intravenous administration for the treatment of cancer: a review of the literature . Patient Prefer. Adherence.10 , 1609 – 1621 ( 2016 ).

- daCosta DiBonaventura M , WagnerJS , GirmanCJet al. Multinational Internet-based survey of patient preference for newer oral or injectable Type II diabetes medication . Patient Prefer. Adherence.4 , 397 – 406 ( 2010 ).

- Smith H . A comprehensive review of rapid-onset opioids for breakthrough pain . CNS Drugs26 ( 6 ), 509 – 535 ( 2012 ).

- Shafer SL , FloodPD . The pharmacology of opioids . In : Geriatric Anesthesiology (2nd Edition) . SilversteinJH , RookeA , RevesJG , McLeskeyCH ( Eds ). Springer Science & Business Media , NY, USA , 209 – 228 ( 2007 ).

- Singla NK , MuseDD , EvashenkMA , PalmerPP . A dose-finding study of sufentanil sublingual microtablets for the management of postoperative bunionectomy pain . J. Trauma Acute Care Surg.77 ( 3 Suppl. 2 ), S198 – S203 ( 2014 ).

- Cepeda MS , AfricanoJM , PoloR , AlcalaR , CarrDB . What decline in pain intensity is meaningful to patients with acute pain?Pain105 ( 1–2 ), 151 – 157 ( 2003 ).