Abstract

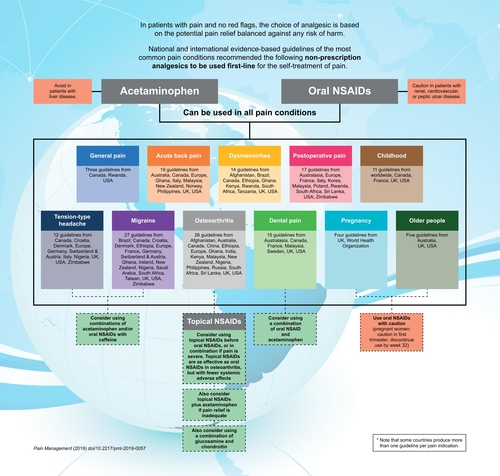

Evidence-based pain guidelines allow recommendation of nonprescription analgesics to patients, facilitating self-care. We researched clinical practice guidelines for common conditions on websites of pain associations, societies, health institutions and organizations, PubMed, ProQuest, Embase, Google Scholar until April 2019. We wanted to determine whether there is a consensus between guidelines. From 114 identified guidelines, migraine (27) and osteoarthritis (26) have been published most around the world, while dysmenorrhea (14) is mainly discussed in developing countries. Specific recommendations to pregnant women, children and older people predominantly come from the UK and USA. We found that acetaminophen and oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) represent first-line management across all pain conditions in adults and children. In osteoarthritis, topical NSAIDs should be considered before oral NSAIDs. This knowledge might persuade patients that using these drugs first could enable fast and effective pain relief.

Background

Clinical guidelines are developed to provide evidence-based recommendations aimed at improving healthcare services and optimizing patient outcomes [Citation1–3]. Such guidelines are now an established component of best practice management, and can aid treatment decision-making [Citation4,Citation5].

Patients frequently present with pain to their primary healthcare provider (whether general medical practitioner, practice nurse or pharmacist).

If – as is usually the case – the pain is not due to serious pathology (i.e., there are no ‘red flags’), the healthcare provider needs to ascertain whether the pain is sufficiently bothersome to require analgesic use, or whether explanation of the benign and time-limited nature of the pain along with expectations of imminent improvement will suffice and thereby avoid analgesic use.

The next challenge for the healthcare provider is to suggest the most appropriate analgesic for the individual patient, considering their age, gender, comorbidities and concomitant medications. It is important to balance potential pain relief against any risk of harm (adverse effects).

Currently, the most widely available therapeutic options for simple analgesia, including over-the-counter medications, are acetaminophen (paracetamol), acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) – all of which have the major advantage of not causing unwanted sedative, cognitive, addictive or other central effects.

However, acetaminophen should be avoided in patients with liver disease, while oral NSAIDs may be risky in those with renal, cardiovascular or peptic ulcer disease.

Importantly, topical NSAIDs are as effective as oral NSAIDs in osteoarthritis, but with fewer systemic adverse effects than oral NSAIDs.

This summary of national and international evidence-based guidelines of the most common pain conditions should help guide primary healthcare providers as to which nonprescription analgesics are widely recommended, including vulnerable groups such as pregnant women, older people and children.

The key point from this review is the consistent message for patients, from many national and international groups: acetaminophen and NSAIDs are the best analgesic options for initial, self-treatment of pain.

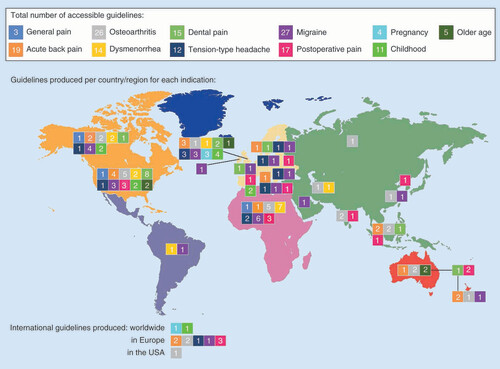

In the management of pain, clinical guidelines can provide much needed assessment of the relative benefits and harms of available analgesic options. Timely relief of acute pain may help to minimize any negative sequelae [Citation6,Citation7]. The increased availability of analgesics at nonprescription doses makes it easier for patients to take control of their own pain and seek appropriate and effective relief. Nevertheless, patients still seek advice from their doctor or pharmacist regarding the best therapy to use. The sheer number of guidelines that are available for each pain condition can be overwhelming, even for doctors and pharmacists (), and is exacerbated by the wide range of prescription and nonprescription options recommended within each guideline. These factors may make it difficult for time-constrained clinicians and pharmacists to recommend initial therapies to their patients.

The figure shows the total number of guidelines produced worldwide per indication (top), the number of guidelines produced for each indication within each country/region (map, color-coded to those along the top) and the number of international guidelines that have been produced for any indications (bottom).

Thus, we decided to nonsystematically review all accessible clinical guidelines within each country (English language only) for the most common pain conditions. Our aim was to look at all drugs recommended within the guidelines and descriptively summarize those that are generally available nonprescription. We wanted to determine whether there is a consensus between guidelines regarding preliminary steps that patients can take to relieve their pain. We have tried to present the information clearly and simply so that it can be used more effectively by busy physicians [Citation8]. We believe that this concise summary may aid decision-making for healthcare providers who are trying to determine the first, most effective and evidence-based step to take in the management of pain.

Common pain conditions

Before looking at the guidelines and the recommendations for treatment of pain, it is worth looking at certain pain conditions that are regularly seen by primary care clinicians, to better appreciate their impact and why it is important that patients effectively treat their pain. Pain negatively interferes with many aspects of life, affecting a person’s ability to perform daily activities, changing their overall perception of general health, increasing the risk of depression and affecting relationships with others – all exacerbated by increasing pain severity [Citation9–11]. The following pain conditions are often experienced by patients at some point during their lifetime, and self-treatment is common; accordingly, nonprescription drugs play an important role in their management.

General pain

People of all ages and from all areas of life can experience pain [Citation12], which may affect up to 60% of the global population every month (depending on the methodology used within each study) [Citation12–14]. The consumption of healthcare resources (e.g., direct medical costs such as physical therapy, pharmacological therapy, inpatient services, primary care costs, etc.) is almost double in patients with pain conditions compared with the general population [Citation12]. Overall, pain can lead to decreased quality of life and increased disability [Citation12].

Acute back pain

One of the most common types of pain affects the lower back [Citation15,Citation16], caused by many factors such as strained ligaments or muscles, disc degeneration, traumatic injury, etc. [Citation17]. Low back pain has a worldwide prevalence of 38% over 1 year [Citation18], and lifetime prevalence of 60–85% [Citation19]. Although recovery may be swift in many people, disability is very common in all age groups [Citation20]. In fact, low back pain was the leading global cause of all disability in 2017 () [Citation21]. The economic cost of back pain is high; in the US, for example, back pain (along with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis) is the most common and costly chronic condition in the US, affecting over 100 million people and costing more than US$200 billion every year [Citation22].

Table 1. Disease burden of common pain conditions, estimated in disability-adjusted life-years and global ranking according to life lived with disability.

Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis is the most common form of arthritis, and joint pain is its most commonly reported and limiting symptom [Citation25]. The physical problems caused by osteoarthritis significantly affect daily living [Citation26] and can lead to psychological distress that is greater than that observed in patients with diabetes, for example [Citation27]. The economic costs of the condition are also high [Citation22]. For example, it has been estimated in the UK that direct costs from topical and oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), NSAID-related iatrogenic events, use of proton-pump inhibitors, hip and knee replacements and arthroscopic surgery were around £1.0 billion (in 2010), while indirect costs (i.e., loss of economic production) were £3.2 billion (in 2002) [Citation28]. As osteoarthritis is mostly found in older people [Citation26], the condition will become an even greater public healthcare problem as the global population ages [Citation29].

Dysmenorrhea

Painful menstruation can affect up to 95% of reproductive-aged women [Citation30], and is a leading cause of absenteeism from school or work [Citation31]. The pain, disruption in daily living and lower quality of life in women with primary dysmenorrhea contributes to a loss of quality-adjusted life years that is comparable with that seen in chronic diseases such as asthma or chronic migraine [Citation32].

Dental pain

Despite increased awareness of the importance of good oral health, oral conditions remain a major global health challenge [Citation33]. One of the most common symptoms associated with many oral disorders is dental pain, and toothache alone has been estimated to affect around 12% of the population in the USA, for example, at any given time [Citation34]. Dental pain is an intensely painful and debilitating experience that has a significant impact on oral health-related quality of life [Citation35], and may account for 40% of pain-related healthcare costs [Citation36].

Tension-type headache

Tension-type headache (TTH) is the most common type of primary headache, with a global age-standardized prevalence of 26.1% in 2016 [Citation37]. It has been estimated that between 30 and 78% of the general population will experience TTH at some point in their lifetime [Citation38]. In 2016, TTH caused 7.2 million years lived with disability (YLDs) [Citation37], compared with 5.9 million YLDs for upper respiratory tract infections, for example [Citation21]. Despite its high socioeconomic impact, it is the least studied of the primary headache disorders [Citation39].

Migraine

Migraine is a recurrent, disabling primary headache disorder [Citation39], with a much lower global prevalence than TTH (14.4% in 2016) [Citation37]. However, migraine is associated with higher disability and is now the second largest cause of YLD (), causing 45.1 million YLDs in 2016 [Citation37]. Together, TTH and migraine comprise 6.5% of all YLDs globally, mainly because medication overuse headache is now considered a sequela of migraine or TTH [Citation37].

Postoperative pain

More than 80% of surgical patients experience postoperative pain [Citation40], which is moderate-to-extreme in approximately 75% of cases [Citation41]. Inadequately controlled pain negatively affects quality of life and functional recovery, and increases the risk of postsurgical complications, including the risk of persistent postoperative pain [Citation41].

Guideline characteristics

We performed a nonsystematic search of several databases (PubMed, ProQuest and Embase) for national and international guidelines (using terms such as ‘treatment’, ‘guidelines/guidance’, ‘consensus’, ‘recommendations/recommend’, ‘best practices’ and ‘quality standards’) (English language only) for common pain conditions (i.e., general pain, acute back pain, osteoarthritis, dysmenorrhea, dental pain, TTH, migraine and postoperative pain). We also searched websites of pain associations, societies, health institutions and organizations, and conducted open searches on Google and Google Scholar. The search included all guidelines until April 2019 (no specific start date), but only the most updated guideline from any given group was included. We excluded reviews, hospital guidelines and hospital surveys, guidelines that did not include nonprescription drugs, guidelines that are no longer valid or have been withdrawn, or were not written in English; we also excluded guidelines that only discussed diagnostic and surgical procedures for the indications mentioned. Further search details can be found at the end of Supplementary Table 1. Assessing the quality of each guideline was outside the scope of our review.

We identified 114 relevant guidelines in adults, as well as four guidelines specifically written for pain in pregnancy, 11 guidelines that address pain in childhood and five guidelines developed for pain in older people (Supplementary Table 1). Most guidelines that we identified were in acute pain conditions, but some were for chronic pain in osteoarthritis or persisting pain in older people. There were some differences in the guidelines produced by each country or region (). For example, developed countries were more likely to produce guidelines for acute back pain, primary headache and dental pain, while guidelines for dysmenorrhea were more prevalent in developing countries.

The methodology used to produce these guidelines varied considerably, and many did not comply with established standards [Citation3,Citation42]. It has been stated that for clinical practice guidelines to be trustworthy, they should be developed by a multidisciplinary panel of experts, based on systematic review of the literature; the evidence should be graded for quality and the strength of the recommendations, and should consider benefits and harms as well as patient values [Citation3,Citation42]. However, in the clinical guidelines that we identified different grading systems were often used to evaluate the quality of the evidence, and drugs were classified in several different ways, for example, using a grade or level, and/or whether they were first or second line and choice. Many did not provide a level of recommendation, but simply recommended a class of drugs based mainly on clinical experience and the reported efficacy and safety. These issues, which are common to many clinical guidelines [Citation43,Citation44], mean that it is difficult to obtain anything other than a general overview of the recommended therapies. Thus, although our summary may be a useful tool, decision makers must also take a closer look at the guidelines specific to their field of expertise.

Nonprescription treatment recommendations for common pain conditions in adults

First-line therapy

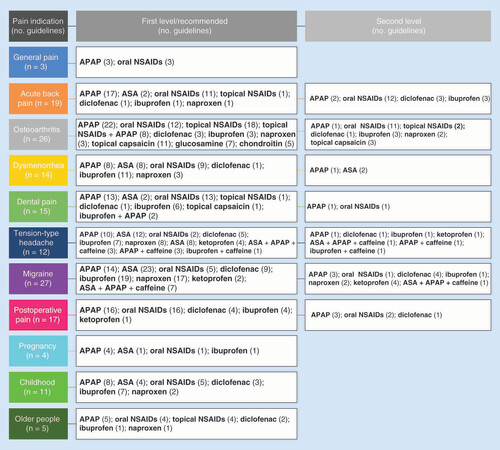

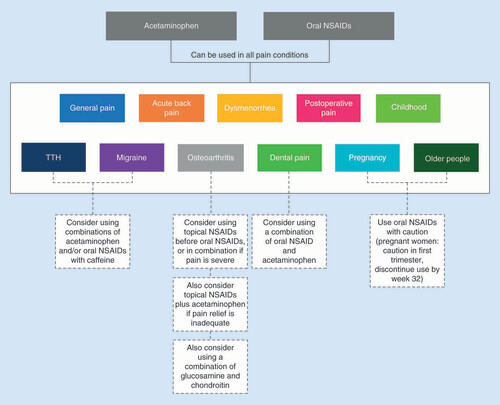

Overwhelmingly, acetaminophen and oral NSAIDs represent the first line of management across all pain conditions in adults, particularly for mild-to-moderate pain (Supplementary Table 2 and ). They are also recommended for severe pain in some cases, such as osteoarthritis [Citation45] and postoperative pain [Citation40,Citation46]. It should be noted that although acetaminophen is recommended throughout all guidelines, recent reviews have questioned its efficacy in some indications [Citation47–50].

Second line

If oral NSAIDs or acetaminophen are insufficient when used alone, it is recommended that they be used in combination [Citation51–59] (for example in dental pain, the combination is considered superior to opioids [Citation52,Citation56–59], because it optimizes efficacy while minimizing acute adverse events [Citation60]).

Topical NSAIDs

Topical NSAIDs are currently specifically recommended in osteoarthritis, and in one guideline each for acute back pain and dental pain (specifically myalgia in temporomandibular disorders). They are often recommended first-line before the use of oral NSAIDs because of their comparable efficacy but lower risk of systemic side effects. In fact, in osteoarthritis oral NSAIDs are more likely to be recommended second-line to topical NSAIDs and to acetaminophen for symptom relief (Supplementary Table 2 and ).

Other analgesic combinations

Some guidelines recommend that topical NSAIDs can be used alongside acetaminophen [Citation26,Citation61–67]. In more severe osteoarthritis pain, it has been recommended that topical NSAIDs be used alongside oral NSAIDs [Citation68]. It is also recommended that glucosamine and chondroitin can be used together to manage osteoarthritis. In primary headache, combinations of acetaminophen and/or NSAIDs with adjunct analgesic caffeine are commonly recommended, and thought to be more effective than any of the active ingredients used alone [Citation69].

First level 1 = grade A, level I or first choice; Second level = grade B, level II or second choice.

APAP: Acetaminophen (paracetamol); ASA: Acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin); NSAID: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Specific NSAID recommendations

It should be noted that some guidelines recommend use of oral NSAIDs at prescription doses, particularly for severe pain or more difficult to treat pain such as back pain or migraine. Often, no dosage at all is specified, apart from a general recommendation to use oral NSAIDs at the lowest effective dose for the shortest duration of time, to minimize the potential for adverse events. There is little differentiation between the oral NSAIDs recommended, although ibuprofen, diclofenac and naproxen are mentioned most often (including ibuprofen for severe pain in dysmenorrhea [Citation70] and diclofenac for severe acute back pain [Citation71,Citation72]). Acetylsalicylic acid is not specifically mentioned in any guideline for osteoarthritis or postoperative pain. The lack of differentiation is most likely because overall, the available evidence indicates that there is little difference between the mean analgesic efficacy of each NSAID [Citation73]. However, individual patient data suggest that there may be variations between patients [Citation73], and a process of trial and error may be necessary to determine which is the most appropriate for each patient. provides an outline of nonprescription treatment options that both patients and healthcare providers may find useful when determining which nonprescription analgesic may be used based on their type of pain. This knowledge may facilitate self-care and enable patients to treat their pain early and effectively, thus potentially minimizing the impact of pain on their quality of life [Citation74].

Where oral NSAIDs are contraindicated or not tolerated, acetaminophen is the treatment of choice, or topical NSAIDs in osteoarthritis. It should be noted that nonpharmacological options (which vary according to the pain indication, but include measures such as physical therapy, lifestyle changes, etc.) are usually recommended alongside pharmacological therapy, for optimal pain relief.

NSAID: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; TTH: Tension-type headache.

Vulnerable groups

Safety concerns are of paramount importance in certain groups of patients, particularly pregnant women, children and older people. Accordingly, guidelines for the management of pain have been specifically developed for these vulnerable groups (Supplementary Table 3), as outlined below.

Pregnant women

There is always concern regarding the use of drugs in pregnant women, mainly because of potential adverse effects on the developing fetus but also because of the risk of adverse drug reactions in the mother [Citation75]. Fear regarding the use of drugs during pregnancy means that some women are at risk of under treatment or no treatment for pain, which can have an adverse impact on health [Citation76]. Nevertheless, nonprescription drugs are used by many pregnant women [Citation75]. Use of the lowest effective dose may be necessary to minimize any risk of maternal, fetal and placental toxicity [Citation75,Citation77].

In all clinical guidelines, acetaminophen is generally considered relatively safe to use in pregnancy and is recommended for use during all stages. It is recommended to avoid oral NSAIDs if possible, but that they may be used if greater analgesia is required; in that case, caution is advised during the first trimester and use should be discontinued by week 32 [Citation78].

Children

Children suffer from many of the same painful conditions as adults, including headaches, sprains and strains, dental pain, cold and flu symptoms and postvaccination pain. For optimal safety, dosing errors in children should be avoided by basing the dose used on their weight and not on their age [Citation79]; weight has been shown to have a greater influence than age on pharmacokinetics and consequently on systemic exposure [Citation80]. However, some guidelines still provide dosages based on age.

For all common painful conditions, acetaminophen and oral NSAIDs are recommended in children, but at lower doses than in adults. If either class of drug is insufficient when used alone, it is recommended that they should be used in combination, for example in children with dental pain [Citation81] or postoperative pain [Citation82]. Acetylsalicylic acid has been recommended in one guideline in France for migraine in children [Citation83]; all others warn against its use in children younger than 12 or 16 years old (depending on the guideline) because of the potential risk of Reye’s syndrome (particularly if recovering from a viral infection [Citation84]).

Older people

Pain is common in older adults (>60 years of age) [Citation85–87]. But treatment of their pain requires careful consideration of various factors, such as age-related physiologic changes, concomitant drug use and comorbidities (e.g., cardiovascular disease and cognitive impairment), which can potentially increase the risk of adverse drug reactions [Citation88,Citation89]. Thus, treatment of pain in older people can be challenging and complex [Citation90,Citation91].

In the guidelines for the management of pain in older adults, acetaminophen is recommended as the first-line treatment. Oral NSAIDs may also be used, but caution is recommended because of the greater risk for drug-related adverse events. It is recommended that oral NSAIDs be used at the lowest possible dose for the shortest duration of time, always monitoring and managing side effects. These recommendations are reflected in the guidelines for adults in general that also mention older people. In the case of osteoarthritis, topical NSAIDs are recommended before the use of oral NSAIDs in older people, to minimize any systemic side effects [Citation64,Citation92].

Conclusion

A review of all accessible national and international clinical guidelines for various pain conditions indicates that acetaminophen and oral NSAIDs are initially recommended to relieve mild-to-moderate pain in adults and in children, although oral NSAIDs should be used with caution in pregnant women and older people. Where oral NSAIDs are contraindicated or not tolerated, acetaminophen is the initial treatment of choice. If either class of drugs is insufficient alone, they may be tried in combination in adults and children but not in pregnant women. In osteoarthritis, topical NSAIDs should be considered before the use of oral NSAIDs to minimize the risk of systemic side effects, particularly in older people. Topical NSAIDs may also be used in combination with acetaminophen in osteoarthritis. All of these analgesics are available nonprescription, which should facilitate self-care by patients and enable them to appropriately treat their pain.

Future perspective

Greater internet access means that patients will be better informed about their disease and available treatment options. Furthermore, healthcare systems will become increasingly expensive, so patients will need to pay for their own treatment. As a result, nonprescription medications will become more common – highlighting the importance of providing evidence-based data not only to clinicians, but also to patients.

Author contributions

M Hagen was involved in the search for the pain treatment guidelines. Both authors contributed to the interpretation of the data and development of the manuscript throughout every stage, and both authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Supplemental Appendix 1

Download Zip (357.2 KB)Infographic

Download PDF (338.1 KB)Supplementary data

An infographic accompanies this paper at the end of the references section. To download the infographic that accompanies this paper, please visit the journal website at: www.tandfonline.com/doi/suppl/10.2217/pmt-2019-0057

Financial & competing interests disclosure

M Hagen is an employee of GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare. J Alchin is an employee of the Canterbury District Health Board, Christchurch, New Zealand, and a member of the GlaxoSmithKline Global Pain Forum, but otherwise declares no conflicts of interest. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

The draft manuscript was prepared by Deborah Nock (Medical WriteAway, Norwich, UK), with full review and approval at all stages by the authors. The services of the medical writer were funded by GSK Consumer Healthcare S.A.

References

- Kredo T , BernhardssonS , MachingaidzeSet al. Guide to clinical practice guidelines: the current state of play. Int. J. Qual. Health Care28(1), 122–128 (2016).

- Graham ID , HarrisonMB. Evaluation and adaptation of clinical practice guidelines. Evid. Based Nurs.8(3), 68–72 (2005).

- Murad MH . Clinical practice guidelines: a primer on development and dissemination. Mayo Clin. Proc.92(3), 423–433 (2017).

- Coleman P , NichollJ. Influence of evidence-based guidance on health policy and clinical practice in England. Qual. Health Care10(4), 229–237 (2001).

- Domenighetti G , GrilliR , LiberatiA. Promoting consumers’ demand for evidence-based medicine. Int. J. Technol. Assess Health Care14(1), 97–105 (1998).

- Sinatra R . Causes and consequences of inadequate management of acute pain. Pain Med.11(12), 1859–1871 (2010).

- Kehlet H , JensenTS , WoolfCJ. Persistent postsurgical pain: risk factors and prevention. Lancet367(9522), 1618–1625 (2006).

- Boudoulas KD , LeierCV , GelerisP , BoudoulasH. The shortcomings of clinical practice guidelines. Cardiology130(3), 187–200 (2015).

- Froud R , PattersonS , EldridgeSet al. A systematic review and meta-synthesis of the impact of low back pain on people’s lives. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord.15, 50 (2014).

- Reid KJ , HarkerJ , BalaMMet al. Epidemiology of chronic non-cancer pain in Europe: narrative review of prevalence, pain treatments and pain impact. Curr. Med. Res. Opin.27(2), 449–462 (2011).

- Doth AH , HanssonPT , JensenMP , TaylorRS. The burden of neuropathic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of health utilities. Pain149(2), 338–344 (2010).

- Henschke N , KamperSJ , MaherCG. The epidemiology and economic consequences of pain. Mayo Clin. Proc.90(1), 139–147 (2015).

- St Sauver JL , WarnerDO , YawnBPet al. Why patients visit their doctors: assessing the most prevalent conditions in a defined American population. Mayo Clin. Proc.88(1), 56–67 (2013).

- Jordan KP , SimJ , MooreA , BernardM , RichardsonJ. Distinctiveness of long-term pain that does not interfere with life: an observational cohort study. Eur. J. Pain16(8), 1185–1194 (2012).

- Breivik H , CollettB , VentafiddaV , CohenR , GallacherD. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur. J. Pain10(4), 287–333 (2006).

- NHS UK . Back pain (2017). www.nhs.uk/conditions/back-pain/

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke . Back Pain Fact Sheet. NIH Publication No. 15–5161 (2014). www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/Patient-Caregiver-Education/Fact-Sheets/Low-Back-Pain-Fact-Sheet

- Hoy D , BainC , WilliamsGet al. A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain. Arthritis Rheum.64, 2027–2037 (2012).

- Krismer M , Van TulderM. Low back pain group of the bone and joint health strategies for Europe project. strategies for prevention and management of musculoskeletal conditions. Low back pain (non-specific). Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol.21(1), 77–91 (2007).

- Ehrlich G . Low back pain. Bull. World Health Organ.81(9), 671–676 (2003).

- GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators . Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet392(10159), 1789–1858 (2018).

- Ma VY , ChanL , CarruthersKJ. Incidence, prevalence, costs, and impact on disability of common conditions requiring rehabilitation in the United States: stroke, spinal cord injury, traumatic brain injury, multiple sclerosis, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, limb loss, and back pain. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil.95(5), 986–995.e981 (2014).

- GBD 2016 Dalys and Hale Collaborators . Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 333 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet390(10100), 1260–1344 (2017).

- Murray CJ , VosT , LozanoRet al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet380(9859), 2197–2223 (2012).

- Hirsh MJ , LozadaCJ. Medical management of osteoarthritis. Hosp. Physician38(2), 57–56 (2002).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Nice) . Osteoarthritis. Care and management. Clin. Guidelines (2014). www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg177

- Penninx BW , BeekmanAT , OrmelJet al. Psychological status among elderly people with chronic diseases: does type of disease play a part? J. Psychosom. Res. 40(5), 521–534 (1996).

- Chen A , GupteC , AkhtarK , SmithP , CobbJ. The global economic cost of osteoarthritis: how the UK compares. Arthritis2012 6987069879 (2012).

- Neogi T . The epidemiology and impact of pain in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage21, 1145–1153 (2013).

- Iacovides S , AvidonI , BakerFC. What we know about primary dysmenorrhea today: a critical review. Hum. Reprod. Update21(6), 762–778 (2015).

- Hailemeskel S , DemissieA , AssefaN. Primary dysmenorrhea magnitude, associated risk factors, and its effect on academic performance: evidence from female university students in Ethiopia. Int. J. Womens Health8, 489–496 (2016).

- Rencz F , PentekM , StalmeierPFMet al. Bleeding out the quality-adjusted life years: evaluating the burden of primary dysmenorrhea using time trade-off and willingness-to-pay methods. Pain158(11), 2259–2267 (2017).

- Kassebaum NJ , SmithAGC , BernabeEet al. Global, regional, and national prevalence, incidence, and disability-adjusted life years for oral conditions for 195 countries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. J. Dent. Res.96(4), 380–387 (2017).

- Heaivilin N , GerbertB , PageJE , GibbsJL. Public health surveillance of dental pain via Twitter. J. Dent. Res.90(9), 1047–1051 (2011).

- Kumarswamy A . Multimodal management of dental pain with focus on alternative medicine: a novel herbal dental gel. Contemp. Clin. Dent.7(2), 131–139 (2016).

- Israel HA , ScrivaniSJ. The interdisciplinary approach to oral, facial and head pain. J. Am. Dent. Assoc.131(7), 919–926 (2000).

- GBD 2016 Headache Collaborators . Global, regional, and national burden of migraine and tension-type headache, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol.17(11), 954–976 (2018).

- ICHD-3 IC . Tension-type headache (TTH) (2018). www.ichd-3.org/2-tension-type-headache/

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (Ihs) . The international classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia33(9), 629–808 (2013).

- Rawal N , DeAndres J , FischerHet al. Postoperative pain management – good clinical practice (2014). www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4745947/pdf/jpr-9-025.pdf

- Chou R , GordonD , DeLeon-Casasola Oet al. Guidelines on the management of postoperative pain. J. Pain17(2), 131–157 (2016).

- IOM (Institute of Medicine) . Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust.The National Academies Press, Washington, DC (2011). www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK209539/

- Shaneyfelt T , Mayo-SmithM , RothwanglJ. Are guidelines following guidelines? The methodological quality of clinical practice guidelines in the peer-reviewed medical literature. JAMA281, 1900–1905 (1999).

- Kung J , MillerRR , MackowiakPA. Failure of clinical practice guidelines to meet institute of medicine standards: two more decades of little, if any, progress. Arch. Intern. Med.172(21), 1628–1633 (2012).

- Sinusas K . Osteoarthritis: diagnosis and treatment. Am. Fam. Physician85(1), 49–56 (2012).

- PROSPECT . Procedure specific postoperative pain management (2015). www.postoppain.org/

- Hunter DJ , Bierma-ZeinstraS. Osteoarthritis. Lancet393(10182), 1745–1759 (2019).

- Stewart M , CibereJ , SayreEC , KopecJA. Efficacy of commonly prescribed analgesics in the management of osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatol. Int.38(11), 1985–1997 (2018).

- Moore RA , MooreN. Paracetamol and pain: the kiloton problem. Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm.23, 187–188 (2016).

- Williams CM , MaherCG , LatimerJet al. Efficacy of paracetamol for acute low-back pain: a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet384(9954), 1586–1596 (2014).

- Hargreaves K . Successful management of acute pain. www.orofacialpain.org.uk/downloads/acute/Summary%20paper%20HargreavesSummitV.pdf

- French-Speaking Society of Oral Medicine and Oral Surgery . Recommendations for prescription of oral anti-inflammatory agents in oral surgery in adults. Médecine Buccale Chirurgie Buccale14(3), (2008).www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16437495

- Wänman A , ErnbergM , ListT. Guidelines in the management of orofacial pain/TMD: an evidence-based approach. Nor Tannlegeforen Tid126, 104–112 (2016).

- Thorson D , BiewenP , BonteB. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Acute pain assessment and opioid prescribing protocol (2014). https://crh.arizona.edu/sites/default/files/u35/Opioids.pdf

- Minnesota Dental Association . MDA Protocol for Assessment and Treatment of Oral/Facial Pain (2016). www.mndental.org/files/Acute-Orofacial-Pain-Assessment-and-Opioid-Prescribing-Protocol.pdf

- Alaska Dental Association . For safe prescribing of opioids and non-opiate alternatives (2018). www.akdental.org/docs/librariesprovider9/opioid/11-18-ads-opioid-amp-nonopioid-alternative-prescribing-guideline.pdf

- New Jersey Dental Association . Resources for safe prescribing of opioids and non-opiate alternatives (2017). www.njda.org/docs/librariesprovider35/private-library-new-jersey/2017-opioids.pdf

- Pennsylvania Dental Association . Pennsylvania guidelines on the use of opioids in dental practice(2015). www.padental.org/Images/OnlineDocs/ResourcesPrograms/Practice%20Management/opioid_dental_prescribing_guidelines3_13_15.pdf

- Schug SA , PalmerGM , ScottDA , HalliwellR , TrincaJ. APM:SE Working Group of the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists and Faculty of Pain Medicine. In: Acute Pain Management: Scientific Evidence (4th Edition). ANZCA & FPM, Melbourne, Australia (2015).

- Moore PA , ZieglerKM , LipmanRD , AminoshariaeA , Carrasco-LabraA , MariottiA. Benefits and harms associated with analgesic medications used in the management of acute dental pain: an overview of systematic reviews. J. Am. Dent. Assoc.149(4), 256–265.e253 (2018).

- Denisov L , TsvetkovaE , GolubevGet al. The European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO) algorithm for the management of knee osteoarthritis is applicable to Russian clinical practice: a consensus statement of leading Russian and ESCEO osteoarthritis experts. Rheumatol. Sci. Pract.54(6), 641–652 (2016).

- Ministry of Health Malaysia . Clinical Practice Guidelines. Management of osteoarthritis (Second edition) (2013). www.acadmed.org.my/index.cfm?&menuid=67

- Best Practice Advocacy Centre New Zealand . Managing pain in osteoarthritis: focus on the person (2018). https://bpac.org.nz/2018/osteoarthritis.aspx

- Kielly J , DavisE , MarraC. Practice guidelines for pharmacists: the management of osteoarthritis. Can. Pharm. J. (Ott.)150(3), 156–168 (2017).

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care . Osteoarthritis of the Knee. Clinical Care Standard (2017). www.safetyandquality.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Osteoarthritis-of-the-Knee-Clinical-Care-Standard-Booklet.pdf

- Ickinger C , TiklyM. Current approach to diagnosis and management of osteoarthritis. SA Fam. Pract.52(5), 382–390 (2010).

- Ministry of Health & Family Welfare Government of India . Standard treatment guidelines: management of ostoarthritis knee (2017). http://clinicalestablishments.gov.in/WriteReadData/31911.pdf

- Qiu G . Chinese Orthopaedic Association. Diagnosis and treatment of osteoarthritis. Orthopaed. Surg.2(1), 1–6 (2010).

- Evers S , AfraJ , FreseAet al. EFNS guideline on the drug treatment of migraine – revised report of an EFNS task force. Eur. J. Neurol.16, 968–981 (2009).

- Ministry of Health for the Republic of Ghana . Standard Treatment Guidelines (2010). http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Js18015en/

- Ministry of Health Royal Republic of Ghana . Chapter 23: disorders of the musculoskeletal system. Low back pain (2010). www.who.int/selection_medicines/country_lists/Ghana_STG_2010.pdf?ua=1

- Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, Ministry of Public Health, General Directorate of Pharmaceutical Affairs. National standard treatment guidelines for the primary level(2013). http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s21744en/s21744en.pdf

- Day RO , GrahamGG. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). BMJ346, f3195 (2013).

- Institute of Medicine . Relieving pain in America: a blueprint for transforming prevention, care, education, and research.The National Academies Press, Washington, DC (2011). www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK91497/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK91497.pdf

- Feghali MN , MattisonDR. Clinical therapeutics in pregnancy. J. Biomed. Biotechnol.2011, 1783528 (2011).

- Babb M , KorenG , EinarsonA. Treating pain during pregnancy. Can. Fam. Physician56(1), 25, 27 (2010).

- Anderson GD . Pregnancy-induced changes in pharmacokinetics: a mechanistic-based approach. Clin. Pharmacokinet.44(10), 989–1008 (2005).

- Flint J , PanchalS , HurrellAet al. BSR and BHPR guideline on prescribing drugs in pregnancy and breastfeeding – Part II: analgesics and other drugs used in rheumatology practice. Rheumatology55(9), 1698–1702 (2016).

- Temple AR , TempleBR , KuffnerEK. Dosing and antipyretic efficacy of oral acetaminophen in children. Clin. Ther.35(9), 1361–1375.e1361-1345 (2013).

- Mohammed BS , EngelhardtT , CameronGAet al. Population pharmacokinetics of single-dose intravenous paracetamol in children. Br. J. Anaesth.108(5), 823–829 (2012).

- Council on Clinical Affairs . Policy on acute pediatric dental pain management (2017). www.aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/P_AcutePainMgmt.pdf

- Association of Paediatric Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland . Good practice in postoperative and procedural pain management, 2nd edition. Paediatr. Anaesth.22(Suppl. 1), 1–79 (2012).

- Lanteri-Minet M , ValadeD , GeraudG , LucasC , DonnetA. Revised French guidelines for the diagnosis and management of migraine in adults and children. J. Headache Pain15(1), 2 (2014).

- Chornomydz I , BoyarchukO , ChornomydzA. Reye (Ray’s) syndrome: a problem everyone should remember. Georgian Med. News (272), 110–118 (2017).

- Savvas SM , GibsonSJ. Overview of pain management in older adults. Clin. Geriatr. Med.32(4), 635–650 (2016).

- Cornelius R , HerrKA , GordonDB , KretzerK , ButcherHK. Evidence-based practice guideline: acute pain management in older adults. J. Gerontol. Nurs.43(2), 18–27 (2017).

- Blyth FM , NoguchiN. Chronic musculoskeletal pain and its impact on older people. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol.31(2), 160–168 (2017).

- Fine PG . Treatment guidelines for the pharmacological management of pain in older persons. Pain Med.13(Suppl. 2), S57–S66 (2012).

- Rastogi R , MeekBD. Management of chronic pain in elderly, frail patients: finding a suitable, personalized method of control. Clin. Interv. Aging8, 37–46 (2013).

- Horgas AL . Pain management in older adults. Nurs. Clin. North Am.52(4), e1–e7 (2017).

- Gaskell H , DerryS , MooreRA. Treating chronic non-cancer pain in older people--more questions than answers?Maturitas79(1), 34–40 (2014).

- Bruyère O , CooperC , PelletierJPet al. A consensus statement on the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO) algorithm for the management of knee osteoarthritis — from evidence-based medicine to the real-life setting. Semin. Arthritis Rheum.45(Suppl. 4), S3–S11 (2016).