Abstract

Buprenorphine is a Schedule III opioid with unique pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties that contribute to effective analgesia and fewer safety risks than other opioids. This review article focuses on the buccal film formulation, which is preferable to other buprenorphine formulations on the basis of bioavailability, safety and efficacy. The clinical studies reviewed here confirm that buprenorphine buccal film offers effective and continuous pain relief that is generally well tolerated, with no cases of respiratory depression reported in any of the studies. On the basis of these clinical data and individual patient risk/benefit assessments, clinicians should consider utilizing buprenorphine buccal film as a first-line opioid treatment for chronic pain over other buprenorphine formulations or other opioids.

On the basis of efficacy and tolerability, buprenorphine is preferable over other opioids for the treatment of chronic pain.

To date, two buprenorphine formulations are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the management of pain severe enough to require daily, around-the-clock, long-term opioid treatment for which alternative treatment options are inadequate: buprenorphine buccal film (Belbuca®, BioDelivery Sciences International, Inc, NC, USA) and the buprenorphine transdermal system (Butrans®, Purdue Pharma, LP, CT, USA).

Of these two formulations, buprenorphine buccal film is better suited for certain patients, as there is access to an extended range of therapeutic doses, increased bioavailability and stronger efficacy and safety data.

In the chronic pain clinical trials assessed here, buprenorphine buccal film demonstrated efficacy in two 12-week double-blind studies, and sustained efficacy was observed in one long-term clinical study.

Buprenorphine buccal film was considered generally well tolerated in all clinical studies to date, with no cases of respiratory depression reported.

Comparison across similar clinical studies of opioids in select patients suggests that buprenorphine buccal film provides efficacy similar to that of Schedule II opioids.

Buprenorphine buccal film should be considered before tramadol (Schedule IV) in some patients on the basis of efficacy and concerns regarding the ultra-rapid or poor metabolism of tramadol.

Buprenorphine buccal film should be considered a preferential treatment option for chronic pain over the buprenorphine transdermal system, tramadol and Schedule II opioids in some patients.

An estimated 20.4% of adults in the USA experience chronic pain [Citation1]. Long-term therapy with full μ-opioid receptor agonists has become a standard approach to pain management [Citation2,Citation3]. Commonly prescribed Schedule II full μ-opioid receptor agonists include hydrocodone, oxycodone, oxymorphone, morphine, codeine and fentanyl [Citation4]. Rising rates of opioid-related deaths, the risk of serious adverse events and government scrutiny deter clinicians from using these drugs for patients with chronic pain [Citation5].

Buprenorphine is a unique, Schedule III, partial μ-opioid receptor agonist option for pain management. Preclinical studies have confirmed the efficacy, benign side-effect profile and low addictive and dependence potential of buprenorphine, all of which are attributed to the partial agonistic and slow dissociative properties at the μ-opioid receptor [Citation6,Citation7]. The functions of buprenorphine at other opioid receptors, such as antagonism at the δ- and κ-opioid receptors and agonism at ORL-1, also contribute to a favorable safety and tolerability profile, as well as antidepressant and antianxiety effects [Citation7,Citation8]. The interactions of buprenorphine at these four opioid receptors contribute to effective analgesia and offer additional advantages over full μ-opioid receptor agonists, including decreased risk of respiratory depression, constipation, immunosuppression and hypogonadism [Citation7–14].

Buprenorphine has a long-standing history of safety and efficacy in chronic pain clinical studies, including those of general chronic pain, osteoarthritis, malignant pain, musculoskeletal pain and chronic low back pain [Citation15–46]. Clinical data also suggest that buprenorphine may be equally effective in men and women, as no differences in plasma levels have been observed between sexes [Citation47,Citation48]. A Phase IV real-world clinical trial demonstrated that buprenorphine has analgesic efficacy comparable with that of the Schedule II opioids morphine, oxycodone and fentanyl in patients with chronic malignant pain [Citation49]. The properties of buprenorphine therefore contribute to effective pain control and an enhanced tolerability profile, which is preferred for chronic pain management when an opioid medication is indicated.

Two buprenorphine formulations are currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the management of pain severe enough to require daily, around-the-clock, long-term opioid treatment for which alternative treatment options are inadequate: buprenorphine buccal film (Belbuca®, BioDelivery Sciences International, Inc, NC, USA) and the buprenorphine transdermal system (Butrans®, Purdue Pharma, LP, CT, USA) [Citation50,Citation51]. These formulations overcome absorption issues that have been observed with oral and sublingual administration [Citation7]. The transdermal and buccal film formulations bypass gastrointestinal and hepatic first-pass metabolism, allowing for enhanced bioavailability and potentially reducing the risk of drug–drug interactions [Citation52–55].

Although effective pain control has been demonstrated for 10–70 μg/h of the buprenorphine transdermal system, providers in the USA are limited to a narrow therapeutic dose range of 5–20 μg/h [Citation37,Citation51,Citation56,Citation57]. The 20 μg/h patch may not provide adequate analgesia in patients receiving higher dose opioid treatment (>80 mg morphine sulfate equivalent/d) [Citation51]. Buprenorphine buccal film is available in seven dose strengths (75, 150, 300, 450, 600, 750 and 900 μg) and is intended for use in patients requiring a morphine sulfate equivalent of up to 160 mg/day [Citation50]. The dose range of buprenorphine buccal film provides more flexibility to titrate to an optimal dose and is a preferable option for patients whose therapeutic needs exceed the dosing capability of the buprenorphine transdermal system [Citation44,Citation58]. Compared with the transdermal formulation, buprenorphine buccal film has increased bioavailability, fewer reports of adverse events, generally greater efficacy and a similar price point () [Citation50,Citation51,Citation54,Citation59–61]. Thus, the properties of buprenorphine buccal film are preferred for the treatment of chronic pain (; ) [Citation45].

Table 1. Comparison of the buprenorphine transdermal system and buprenorphine buccal film.

Buprenorphine buccal film is a small, bilayered dissolving polymer film that adheres to the buccal mucosa using BioErodible MucoAdhesive® technology, which enhances bioavailability compared with other routes of administration [Citation59]. Buprenorphine buccal film is available in 75, 150, 300, 450, 600, 750 and 900 μg dosage strengths and facilitates a unidirectional flow of the drug that is approximately 46–65% bioavailable and reaches steady-state levels in approximately 3 days [Citation50,Citation54].

![Figure 1. Buprenorphine buccal film. Buprenorphine buccal film is a small, bilayered dissolving polymer film that adheres to the buccal mucosa using BioErodible MucoAdhesive® technology, which enhances bioavailability compared with other routes of administration [Citation59]. Buprenorphine buccal film is available in 75, 150, 300, 450, 600, 750 and 900 μg dosage strengths and facilitates a unidirectional flow of the drug that is approximately 46–65% bioavailable and reaches steady-state levels in approximately 3 days [Citation50,Citation54].](/cms/asset/a1412f9f-893f-483e-9211-0682168a2915/ipmt_a_12344370_f0001.jpg)

Buprenorphine buccal film has advantages over the transdermal formulation and is considered by many practitioners to be a preferential treatment option over Schedule II opioids on the basis of efficacy and safety demonstrated by clinical studies [Citation44–46,Citation62]. This review article is thus focused on the buccal formulation, with the primary objective of providing an overview of the clinical studies that have examined buprenorphine buccal film as a resource for clinicians who are seeking alternative treatments for chronic pain.

Buprenorphine buccal film clinical trials

Efficacy

Two pivotal Phase III, multicenter, 12-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled, enriched-enrollment, randomized-withdrawal clinical trials evaluated the safety and efficacy of buprenorphine buccal film (75–900 μg/12 h) in opioid-experienced and opioid-naive patients with chronic low back pain (A & B) [Citation44,Citation46]. An additional open-label, single-arm, 48-week study was performed to evaluate the long-term safety and efficacy of buprenorphine buccal film (150–900 μg/12 h) [Citation45]. The open-label study examined opioid-experienced and opioid-naive rollover patients from the two double-blind studies as well as a third cohort of newly recruited de novo patients (C) [Citation45].

The safety and efficacy of buprenorphine buccal film were studied in two double-blind, Phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled trials in (A) opioid-experienced [Citation44] and (B) opioid-naive [Citation46] patients that comprised a 2-week screening phase; an open-label titration phase; a 12-week double-blind, placebo-controlled treatment phase; and follow-up. An analgesic taper phase was also included for opioid-experienced patients. (C) The long-term study [Citation45] included rollover patients from (A & B) or de novo recruits and was comprised of a dose-titration period of ≤6 weeks with buprenorphine buccal film; patients who achieved and maintained an optimal dose (300–900 μg/12 h) for ≥7 days continued treatment for a long-term period up to 48 weeks.

![Figure 2. Design of buprenorphine buccal film clinical trials in patients with chronic low back pain. The safety and efficacy of buprenorphine buccal film were studied in two double-blind, Phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled trials in (A) opioid-experienced [Citation44] and (B) opioid-naive [Citation46] patients that comprised a 2-week screening phase; an open-label titration phase; a 12-week double-blind, placebo-controlled treatment phase; and follow-up. An analgesic taper phase was also included for opioid-experienced patients. (C) The long-term study [Citation45] included rollover patients from (A & B) or de novo recruits and was comprised of a dose-titration period of ≤6 weeks with buprenorphine buccal film; patients who achieved and maintained an optimal dose (300–900 μg/12 h) for ≥7 days continued treatment for a long-term period up to 48 weeks.](/cms/asset/4a4fd90f-cf4c-46da-afa2-f21a326f71b5/ipmt_a_12344370_f0002.jpg)

In the double-blind opioid-experienced study, a total of 810 patients entered the open-label titration phase, 510 of them were randomized and treated (n = 254, buprenorphine; n = 256, placebo) [Citation44]. In the double-blind opioid-naive study, 749 patients entered the open-label titration phase, and 461 were randomized and treated (n = 229, buprenorphine; n = 232, placebo) [Citation46]. In the long-term study, 506 patients entered the titration phase (445 rollover patients and 61 de novo patients), and 435 patients entered the long-term treatment phase [Citation45].

The randomized-withdrawal design utilized in the double-blind studies examines efficacy by comparing the increase in pain between those randomized to placebo and those who continue on active study treatment [Citation44]. In the double-blind studies, the primary efficacy end point was change in mean daily average pain intensity scores from baseline (after the open-label titration phase) to week 12 using an 11-point numerical rating scale [Citation44,Citation46].

In opioid-experienced and opioid-naive patients, numerical rating scale pain scores increased significantly more from baseline to week 12 in those randomized to placebo than in those continuing to receive buprenorphine buccal film (p < 0.001 and p = 0.0012, respectively; ) [Citation44,Citation46]. These results indicate that buprenorphine buccal film provided greater pain relief than placebo [Citation44,Citation46]. In addition, the buprenorphine buccal film group in each study had significantly lower pain scores throughout all 12 weeks than the placebo group [Citation44,Citation46].

Primary sensitivity analyses comparing the change from baseline to week 12 in numerical rating scale pain intensity scores in patients receiving placebo compared with those receiving buprenorphine buccal film.

LCL: Lower confidence limit; UCL: Upper confidence limit.

Data taken from [Citation44,Citation46].

![Figure 3. Double-blind studies: buprenorphine buccal film significantly reduced pain intensity scores compared with placebo in patients with chronic low back pain. Primary sensitivity analyses comparing the change from baseline to week 12 in numerical rating scale pain intensity scores in patients receiving placebo compared with those receiving buprenorphine buccal film.LCL: Lower confidence limit; UCL: Upper confidence limit.Data taken from [Citation44,Citation46].](/cms/asset/1ca00dba-4551-4039-a6ef-daaf39c3d3b5/ipmt_a_12344370_f0003.jpg)

In the long-term open-label study, efficacy was measured as change from baseline in mean daily average pain intensity scores throughout the titration and long-term treatment phases using an 11-point numerical rating scale [Citation45]. At the start of initial titration, all patients (including rollover patients) received buprenorphine buccal film 150 μg/12 h, regardless of the previous dose, which was then titrated to an optimal dose [Citation45]. In the titration phase, numerical rating scale pain intensity scores briefly increased in rollover patients because of a rapid decrease in dose at the start of the titration phase [Citation45]. During long-term treatment with an optimal dose, mean numerical rating scale scores remained decreased and stable until the end of the treatment phase at week 48, supporting sustained efficacy [Citation45]. In addition, the dose of buprenorphine buccal film remained unchanged in 86.2% of patients over the 48 weeks of treatment, confirming efficacious treatment with an optimal dose and nontolerance.

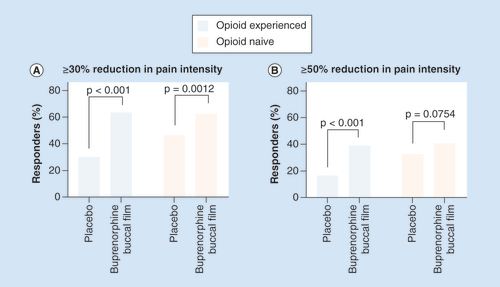

In the double-blind studies, the proportion of patients who experienced a ≥30 or ≥50% decrease in numerical rating scale pain intensity scores at week 12 of the double-blind phase was also assessed [Citation44,Citation46]. In the opioid-experienced population, a significantly greater percentage of patients receiving buprenorphine buccal film achieved ≥30 or ≥50% pain reduction compared with the placebo group (p < 0.001; ) [Citation44]. In the opioid-naive population, a significantly greater percentage of patients receiving buprenorphine buccal film achieved ≥30% pain reduction compared with the placebo group (p = 0.0012; ) [Citation46]. However, the proportion of patients achieving ≥50% pain reduction was not significantly different between groups (p = 0.0754), which was likely due to a higher placebo response in opioid-naive patients () [Citation46].

The percentage of patients achieving ≥30% (A) or ≥50% (B) pain reduction from the period before the open-label titration to week 12 of the double-blind treatment phase.

To further evaluate the efficacy of buprenorphine buccal film, the use of rescue medication (hydrocodone/acetaminophen or acetaminophen alone) was also determined in both studies [Citation44,Citation46]. In each double-blind study, the placebo group required more rescue medication than the buprenorphine group [Citation44,Citation46]. During the open-label long-term study, the use of rescue medication was low (∼3.0 tablets per day) during the titration phase and decreased further during the long-term phase (∼1 tablet per day) [Citation45].

To determine the impact on quality of life in both double-blind studies, patient-reported impression of changes in activity limitation and treatment benefits were measured with Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC) scores, and low back pain as a health status marker was measured with the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ) [Citation44,Citation46]. In both studies, change in PGIC scores favored those randomized to buprenorphine buccal film over those randomized to placebo (p < 0.001 for opioid-experienced patients and p = 0.0011 for opioid-naive patients) [Citation44,Citation46]. RMDQ scores were lower in the buprenorphine group than in the placebo group in both studies, indicating better function [Citation44,Citation46]. Patient satisfaction with buprenorphine buccal film treatment was also high, as indicated by the percentage of patients completing the double-blind studies who continued in the long-term safety study (445/549; 81.1%) [Citation44–46].

Safety

During open-label titration with buprenorphine buccal film in the double-blind studies, the most common adverse events were those typically associated with opioids, including nausea, constipation, vomiting, headache, dizziness and somnolence () [Citation44,Citation46]. Nausea was the most common adverse event, occurring in 49.8% of opioid-naive patients; however, drug-induced nausea is acute and commonly subsides [Citation44,Citation46,Citation63]. In the long-term study, nausea and constipation occurred during open-label titration, although to a lesser extent than what was observed in the double-blind studies () [Citation44–46].

Table 2. Adverse events occurring in ≥5% of patients receiving buprenorphine buccal film during open-label titration in at least one study.

Following open-label titration, the number of adverse events decreased during double-blind treatment [Citation44,Citation46]. Nausea and vomiting occurred in ≤10% and constipation in <5% of opioid-experienced and opioid-naive patients receiving buprenorphine buccal film in the double-blind studies; the incidence of these adverse events remained low during the long-term study () [Citation44–46]. Importantly, no cases of respiratory depression were observed in any of the studies [Citation44–46].

Table 3. Adverse events occurring in ≥5% of patients receiving buprenorphine buccal film during the double-blind or long-term treatment studies.

Switching to buprenorphine buccal film from a full μ-opioid receptor agonist

An additional double-blind crossover study was performed in an opioid-experienced population (≥80 but ≤220 mg/day morphine sulfate equivalent) who had general chronic pain [Citation64]. Switching to buprenorphine buccal film from a full μ-opioid receptor agonist at approximately 50% of the dose (a common reduction with opioid rotation) did not increase opioid withdrawal or result in loss of pain control [Citation64]. Although the sample size of this study was small (n = 39), the authors concluded that chronic pain patients treated with full μ-opioid agonists could be switched to buccal buprenorphine film at approximately 50% of the full μ-opioid receptor agonist dose without an increased risk of opioid withdrawal or loss of pain control [Citation64].

Discussion

Efficacy

Buprenorphine buccal film demonstrated efficacy in two 12-week double-blind studies and an additional long-term clinical study [Citation44–46]. Of note, the long-term efficacy of buprenorphine buccal film is supported by reduced pain levels that were generally maintained throughout a 48-week treatment period and were accompanied by low use of rescue medication [Citation45]. These findings support the concept that the classification of buprenorphine as a partial μ-opioid receptor agonist does not translate to partial clinical analgesic efficacy, which is commonly and inaccurately assumed on the basis of receptor activity [Citation65].

In opioid-experienced patients, buprenorphine buccal film had efficacy comparable with that of the extended-release full μ-opioid receptor agonists hydromorphone, hydrocodone and oxymorphone, as demonstrated by ≥30 and ≥50% response rates in similar studies () [Citation37,Citation44,Citation66–68]. As a partial μ-opioid receptor agonist, buprenorphine is thus equally effective as full μ-opioid receptor agonists for the treatment of chronic pain; however, head-to-head clinical trials are needed to confirm these comparisons [Citation69].

Table 4. Response rates across similar studies of opioids.

Clinicians commonly prefer the use of a Schedule IV pain reliever, such as tramadol, because of its scheduling and believe that tramadol and buprenorphine provide similar efficacy. However, clinical data show buprenorphine to be more efficacious than tramadol in providing pain relief [Citation70]. This was confirmed by a clinical study that showed resting pain scores, pain upon movement and rescue analgesia requirements to be significantly lower in patients who received transdermal buprenorphine than in those who received oral tramadol [Citation70]. If a clinician prefers to use tramadol on the basis of its Schedule IV classification, the risk/benefit assessment should take into account the possibility that the patient is an ultra-rapid or poor metabolizer of the drug [Citation71]. Ultra-rapid metabolizers have an increased risk for respiratory depression, whereas poor metabolizers commonly experience limited analgesic efficacy [Citation71]. In addition, reported pain reliever misuse has been higher with tramadol than with buprenorphine [Citation72]. Thus, buprenorphine is preferable to tramadol in appropriately selected patients because of expected enhanced efficacy [Citation73].

Safety

In the clinical studies presented here, buprenorphine buccal film was considered to be well tolerated, with no cases of respiratory depression reported [Citation44–46]. Unlike morphine and fentanyl, buprenorphine has a ceiling effect on respiratory depression at higher doses [Citation74,Citation75], which is why respiratory depression is a titration-limiting factor with full μ-opioid receptor agonists [Citation14]. The US Department of Health and Human Services Pain Management Best Practices Inter-Agency Task Force agrees that buprenorphine is safer than full μ-opioid receptor agonists such as morphine, hydrocodone and oxycodone on the basis of this reduced potential for respiratory depression [Citation76]. The unique pharmacodynamic properties of buprenorphine, such as partial agonism at the μ-opioid receptor, may therefore contribute to fewer adverse events compared with full μ-opioid receptor agonists [Citation76,Citation77]. However, head-to-head trials are warranted to make direct comparisons.

A Phase I placebo-controlled study is currently evaluating the dose-dependent effects of buprenorphine buccal film compared with those of oral oxycodone hydrochloride on respiratory function, tolerability and pharmacokinetics in recreational opioid users who are not opioid dependent (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03996694) [Citation78]. The results of this pending study will provide insight into the physiological differences in effects on respiratory function between a full μ-opioid receptor agonist and a partial agonist.

Because of potential safety concerns with Schedule II opioids, such as quantity, refill and dosage limits, various federal and state barriers are associated with their prescription [Citation79]. Buprenorphine’s Schedule III classification bypasses these issues [Citation79]. A special prescribing waiver is specific to buprenorphine products with indications for medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder; a wavier is not required for the transdermal and buccal film formulations because they are indicated for chronic pain and have proven safety and efficacy [Citation37,Citation44–46,Citation50,Citation56,Citation80]. The US Department of Health and Human Services Pain Management Best Practices Inter-Agency Task Force recommendations encourage the primary use of buprenorphine for chronic pain, rather than use only after failure of standard full μ-opioid receptor agonists such as hydrocodone or fentanyl, when clinically indicated [Citation76].

Conclusion

The clinical data presented here support buprenorphine buccal film as a generally well-tolerated treatment option for chronic pain that effectively and continuously reduces pain. The Schedule III classification of buprenorphine by the US Drug Enforcement Administration confirms its enhanced safety profile and reduced abuse potential [Citation77]. As a result, buprenorphine should be considered a first-line treatment for chronic pain in appropriate patients identified by risk/benefit analyses [Citation62]. The increased bioavailability (46–65%) and extended available dose range (75–900 μg) of buprenorphine buccal film compared with that of the buprenorphine transdermal system support its preferential consideration for chronic pain treatment. These characteristics combined with The US Department of Health and Human Services Pain Management Best Practices Inter-Agency Task Force recommendations support buprenorphine buccal film as a first-line treatment option for chronic pain management at a time when better-tolerated options are needed.

Future perspective

Until new nonopioid analgesics are developed, buprenorphine buccal film represents an effective Schedule III treatment option for chronic pain. We anticipate that buprenorphine buccal film will become the preferred treatment option for chronic pain over other opioids.

Author contributions

All authors directed the content of the manuscript, critically revised the manuscript for scientific accuracy and intellectual content and approved the final manuscript for publication.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

M Hale was a principal investigator for one or more of the clinical trials discussed here and has served on advisory boards for BioDelivery Sciences International, Inc. J Gimbel was a principal investigator for one or more of the clinical trials discussed here. R Rauck has received research funding and has served as a consultant and speaker for BioDelivery Sciences International, Inc. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Medical writing support was provided by J Brunquell, of MedLogix Communications, LLC, under the direction of the authors and was funded by BioDelivery Sciences International, Inc.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Dahlhamer J , LucasJ , ZelayaCet.al Prevalence of chronic pain and high-impact chronic pain among adults - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep.67(36), 1001–1006 (2018).

- Davis MP , PasternakG , BehmB. Treating chronic pain: an overview of clinical studies centered on the buprenorphine option. Drugs78(12), 1211–1228 (2018).

- Reuben DB , AlvanzoAA , AshikagaTet.al National Institutes of Health pathways to prevention workshop: the role of opioids in the treatment of chronic pain. Ann. Intern. Med.162(4), 295–300 (2015).

- National Institute on Drug Abuse . Prescription opioids (2019). https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/prescription-opioids

- Hedegaard H , MiniñoAM , WarnerM. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2017. NCHS Data Brief No. 329, November 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db329.htm

- Tzschentke TM . Behavioral pharmacology of buprenorphine, with a focus on preclinical models of reward and addiction. Psychopharmacology (Berl)161(1), 1–16 (2002).

- Gudin J , FudinJ. A narrative pharmacological review of buprenorphine: a unique opioid for the treatment of chronic pain. Pain Ther. doi:10.1007/s40122-019-00143-6 (2020) ( Epub ahead of print).

- Khanna IK , PillarisettiS. Buprenorphine – an attractive opioid with underutilized potential in treatment of chronic pain. J. Pain Res.8, 859–870 (2015).

- Ahmadi J , JahromiMS , EhsaeiZ. The effectiveness of different singly administered high doses of buprenorphine in reducing suicidal ideation in acutely depressed people with co-morbid opiate dependence: a randomized, double-blind, clinical trial. Trials19(1), 462 (2018).

- Likar R . Transdermal buprenorphine in the management of persistent pain - safety aspects. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag.2(1), 115–125 (2006).

- Rothman RB , GorelickDA , HeishmanSJet.al An open-label study of a functional opioid kappa antagonist in the treatment of opioid dependence. J. Subst. Abuse Treat.18(3), 277–281 (2000).

- Stein C , MachelskaH. Modulation of peripheral sensory neurons by the immune system: implications for pain therapy. Pharmacol. Rev.63(4), 860–881 (2011).

- Hallinan R , ByrneA , AghoK , McmahonCG , TynanP , AttiaJ. Hypogonadism in men receiving methadone and buprenorphine maintenance treatment. Int. J. Androl.32(2), 131–139 (2009).

- Davis MP . Twelve reasons for considering buprenorphine as a frontline analgesic in the management of pain. J. Support. Oncol.10(6), 209–219 (2012).

- Böhme K . Buprenorphine in a transdermal therapeutic system – a new option. Clin. Rheumatol.21(Suppl. 1), S13–S16 (2002).

- Breivik H , LjosaaTM , Stengaard-PedersenKet.al A 6-months, randomised, placebo-controlled evaluation of efficacy and tolerability of a low-dose 7-day buprenorphine transdermal patch in osteoarthritis patients naïve to potent opioids. Scand. J. Pain1(3), 122–141 (2010).

- Gianni W , MadaioAR , CeciMet.al Transdermal buprenorphine for the treatment of chronic noncancer pain in the oldest old. J. Pain Symptom Manage.41(4), 707–714 (2011).

- Gordon A , CallaghanD , SpinkDet.al Buprenorphine transdermal system in adults with chronic low back pain: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study, followed by an open-label extension phase. Clin. Ther.32(5), 844–860 (2010).

- Gordon A , RashiqS , MoulinDEet.al Buprenorphine transdermal system for opioid therapy in patients with chronic low back pain. Pain Res. Manage.15(3), 169–178 (2010).

- Hakl M . Transdermal buprenorphine in clinical practice: a multicenter, postmarketing study in the Czech Republic, with a focus on neuropathic pain components. Pain Manage.2(2), 169–175 (2012).

- Karlsson J , SöderströmA , AugustiniBG , BerggrenAC. Is buprenorphine transdermal patch equally safe and effective in younger and elderly patients with osteoarthritis-related pain? Results of an age-group controlled study. Curr. Med. Res. Opin.30(4), 575–587 (2014).

- Karlsson M , BerggrenAC. Efficacy and safety of low-dose transdermal buprenorphine patches (5, 10, and 20 μg/h) versus prolonged-release tramadol tablets (75, 100, 150, and 200 mg) in patients with chronic osteoarthritis pain: a 12-week, randomized, open-label, controlled, parallel-group noninferiority study. Clin. Ther.31(3), 503–513 (2009).

- Leng X , LiZ , LvHet.al Effectiveness and safety of transdermal buprenorphine versus sustained-release tramadol in patients with moderate to severe musculoskeletal pain: an 8-week, randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, multicenter, active-controlled, noninferiority study. Clin. J. Pain31(7), 612–620 (2015).

- Likar R , KayserH , SittlR. Long-term management of chronic pain with transdermal buprenorphine: a multicenter, open-label, follow-up study in patients from three short-term clinical trials. Clin. Ther.28(6), 943–952 (2006).

- Likar R , LorenzV , Korak-LeiterM , KagerI , SittlR. Transdermal buprenorphine patches applied in a 4-day regimen versus a 3-day regimen: a single-site, Phase III, randomized, open-label, crossover comparison. Clin. Ther.29(8), 1591–1606 (2007).

- Likar R , VadlauEM , BreschanC , KagerI , Korak-LeiterM , ZiervogelG. Comparable analgesic efficacy of transdermal buprenorphine in patients over and under 65 years of age. Clin. J. Pain24(6), 536–543 (2008).

- Miller K , YarlasA , WenWet.al Buprenorphine transdermal system and quality of life in opioid-experienced patients with chronic low back pain. Expert Opin. Pharmacother.14(3), 269–277 (2013).

- Miller K , YarlasA , WenWet.al The impact of buprenorphine transdermal delivery system on activities of daily living among patients with chronic low back pain: an application of the international classification of functioning, disability and health. Clin. J. Pain30(12), 1015–1022 (2014).

- Pace MC , PassavantiMB , GrellaEet.al Buprenorphine in long-term control of chronic pain in cancer patients. Front. Biosci.12, 1291–1299 (2007).

- Pota V , BarbarisiM , SansonePet.al Combination therapy with transdermal buprenorphine and pregabalin for chronic low back pain. Pain Manage.2(1), 23–31 (2012).

- Ripa SR , MccarbergBH , MuneraC , WenW , LandauCJ. A randomized, 14-day, double-blind study evaluating conversion from hydrocodone/acetaminophen (Vicodin) to buprenorphine transdermal system 10 μg/h or 20 μg/h in patients with osteoarthritis pain. Expert Opin. Pharmacother.13(9), 1229–1241 (2012).

- Serpell M , TripathiS , ScherzingerS , Rojas-FarrerasS , OkscheA , WilsonM. Assessment of transdermal buprenorphine patches for the treatment of chronic pain in a UK observational study. Patient9(1), 35–46 (2016).

- Silverman S , RaffaRB , CataldoMJ , KwarcinskiM , RipaSR. Use of immediate-release opioids as supplemental analgesia during management of moderate-to-severe chronic pain with buprenorphine transdermal system. J. Pain Res.10, 1255–1263 (2017).

- Sittl R , GriessingerN , LikarR. Analgesic efficacy and tolerability of transdermal buprenorphine in patients with inadequately controlled chronic pain related to cancer and other disorders: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin. Ther.25(1), 150–168 (2003).

- Skvarc NK . Transdermal buprenorphine in clinical practice: results from a multicenter, noninterventional postmarketing study in Slovenia. Pain Manage.2(2), 177–183 (2012).

- Sorge J , SittlR. Transdermal buprenorphine in the treatment of chronic pain: results of a Phase III, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Clin. Ther.26(11), 1808–1820 (2004).

- Steiner D , MuneraC , HaleM , RipaS , LandauC. Efficacy and safety of buprenorphine transdermal system (BTDS) for chronic moderate to severe low back pain: a randomized, double-blind study. J. Pain12(11), 1163–1173 (2011).

- Steiner DJ , SitarS , WenWet.al Efficacy and safety of the seven-day buprenorphine transdermal system in opioid-naïve patients with moderate to severe chronic low back pain: an enriched, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J. Pain Symptom Manage.42(6), 903–917 (2011).

- Vondráčková D . Transdermal buprenorphine in clinical practice: a multicenter, noninterventional postmarketing study in the Czech Republic. Pain Manage.2(2), 163–168 (2012).

- Yarlas A , MillerK , WenWet.al A randomized, placebo-controlled study of the impact of the 7-day buprenorphine transdermal system on health-related quality of life in opioid-naïve patients with moderate-to-severe chronic low back pain. J. Pain14(1), 14–23 (2013).

- Yarlas A , MillerK , WenWet.al Buprenorphine transdermal system compared with placebo reduces interference in functioning for chronic low back pain. Postgrad. Med.127(1), 38–45 (2015).

- James IG , O’brienCM , McdonaldCJ. A randomized, double-blind, double-dummy comparison of the efficacy and tolerability of low-dose transdermal buprenorphine (BuTrans seven-day patches) with buprenorphine sublingual tablets (Temgesic) in patients with osteoarthritis pain. J. Pain Symptom Manage.40(2), 266–278 (2010).

- Yarlas A , MillerK , WenWet.al Buprenorphine transdermal system improves sleep quality and reduces sleep disturbance in patients with moderate-to-severe chronic low back pain: results from two randomized controlled trials. Pain Pract.16(3), 345–358 (2016).

- Gimbel J , SpieringsEL , KatzN , XiangQ , TzanisE , FinnA. Efficacy and tolerability of buccal buprenorphine in opioid-experienced patients with moderate to severe chronic low back pain: results of a Phase 3, enriched enrollment, randomized withdrawal study. Pain157(11), 2517–2526 (2016).

- Hale M , UrdanetaV , KirbyMT , XiangQ , RauckR. Long-term safety and analgesic efficacy of buprenorphine buccal film in patients with moderate-to-severe chronic pain requiring around-the-clock opioids. J. Pain Res.10, 233–240 (2017).

- Rauck RL , PottsJ , XiangQ , TzanisE , FinnA. Efficacy and tolerability of buccal buprenorphine in opioid-naive patients with moderate to severe chronic low back pain. Postgrad. Med.128(1), 1–11 (2016).

- Bullingham RE , McquayHJ , DwyerD , AllenMC , MooreRA. Sublingual buprenorphine used postoperatively: clinical observations and preliminary pharmacokinetic analysis. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol.12(2), 117–122 (1981).

- Moody DE , FangWB , MorrisonJ , Mccance-KatzE. Gender differences in pharmacokinetics of maintenance dosed buprenorphine. Drug Alcohol Depend.118(2-3), 479–483 (2011).

- Corli O , FlorianiI , RobertoAet.al Are strong opioids equally effective and safe in the treatment of chronic cancer pain? A multicenter randomized Phase IV ‘real life’ trial on the variability of response to opioids. Ann. Oncol.27(6), 1107–1115 (2016).

- Belbuca [package insert] . BioDelivery Sciences International, Inc.Raleigh, NC, USA (2019).

- Butrans [package insert] . Purdue Pharma L.P. Stamford, CT, USA (2019).

- Ahn JS , LinJ , OgawaSet.al Transdermal buprenorphine and fentanyl patches in cancer pain: a network systematic review. J. Pain Res.10, 1963–1972 (2017).

- Kapil RP , CiprianoA , FriedmanKet.al Once-weekly transdermal buprenorphine application results in sustained and consistent steady-state plasma levels. J. Pain Symptom Manage.46(1), 65–75 (2013).

- Pergolizzi JV Jr , RaffaRB , FleischerC , ZampognaG , TaylorRJr. Management of moderate to severe chronic low back pain with buprenorphine buccal film using novel bioerodible mucoadhesive technology. J. Pain Res.9, 909–916 (2016).

- Robinson SE . Buprenorphine: an analgesic with an expanding role in the treatment of opioid addiction. CNS Drug Rev.8(4), 377–390 (2002).

- Steiner DJ , SitarS , WenWet.al Efficacy and safety of the seven-day buprenorphine transdermal system in opioid-naive patients with moderate to severe chronic low back pain: an enriched, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J. Pain Symptom Manage.42(6), 903–917 (2011).

- Skvarc NK . Transdermal buprenorphine in clinical practice: results from a multicenter, noninterventional postmarketing study in Slovenia. Pain Manag.2(2), 177–183 (2012).

- Priestley T , ChappaAK , MouldDRet.al Converting from transdermal to buccal formulations of buprenorphine: a pharmacokinetic meta-model simulation in healthy volunteers. Pain Med.19(10), 1988–1996 (2018).

- Webster LR , SmithMD , UnalC , FinnA. Low-dose naloxone provides an abuse-deterrent effect to buprenorphine. J. Pain Res.8, 791–798 (2015).

- goodRX . Belbuca (2020). https://www.goodrx.com/belbuca?dosage=75mcg&form=film&label_override=Belbuca&quantity=60

- goodRX . Butrans buprenorphine (2020). https://www.goodrx.com/butrans?dosage=4-patches-of-5mcg&form=carton&label_override=Butrans&quantity=1

- Fishman MA , SchererA , TopferJ , KimPSH. Limited access to on-label formulations of buprenorphine for chronic pain as compared with conventional opioids. Pain Med.(2019) ( Epub ahead of print).

- Aung T , SooS. Drugs induced nausea and vomiting: an overview. J. Pharm. Biol. Sci.11(3), 5–9 (2016).

- Webster L , GruenerD , KirbyT , XiangQ , TzanisE , FinnA. Evaluation of the tolerability of switching patients on chronic full mu-opioid agonist therapy to buccal buprenorphine. Pain Med.17(5), 899–907 (2016).

- Raffa RB , HaideryM , HuangHMet.al The clinical analgesic efficacy of buprenorphine. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther.39(6), 577–583 (2014).

- Opana ER [package insert] . Endo Pharmaceuticals, Inc. PA, USA (2019).

- Hale M , KhanA , KutchM , LiS. Once-daily OROS hydromorphone ER compared with placebo in opioid-tolerant patients with chronic low back pain. Curr. Med. Res. Opin.26(6), 1505–1518 (2010).

- Rauck RL , NalamachuS , WildJEet.al Single-entity hydrocodone extended-release capsules in opioid-tolerant subjects with moderate-to-severe chronic low back pain: a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Pain Med.15(6), 975–985 (2014).

- Pergolizzi JV Jr , RaffaRB. Safety and efficacy of the unique opioid buprenorphine for the treatment of chronic pain. J. Pain Res.12, 3299–3317 (2019).

- Desai SN , BadigerSV , TokurSB , NaikPA. Safety and efficacy of transdermal buprenorphine versus oral tramadol for the treatment of post-operative pain following surgery for fracture neck of femur: a prospective, randomised clinical study. Indian J. Anaesth.61(3), 225–229 (2017).

- Pattinson KT . Opioids and the control of respiration. Br. J. Anaesth.100(6), 747–758 (2008).

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP19-5068, NSDUH Series H-54). Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, MD (2019). https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHNationalFindingsReport2018/NSDUHNationalFindingsReport2018.pdf

- Webster L , GudinJ , RaffaRBet.al Understanding buprenorphine for use in chronic pain: expert opinion. Pain Med.21(4), 714–723 (2020).

- Walsh SL , PrestonKL , BigelowGE , StitzerML. Acute administration of buprenorphine in humans: partial agonist and blockade effects. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther.274(1), 361–372 (1995).

- Dahan A , YassenA , BijlHet.al Comparison of the respiratory effects of intravenous buprenorphine and fentanyl in humans and rats. Br. J. Anaesth.94(6), 825–834 (2005).

- US Department of Health and Human Services . Report on pain management best practices: updates, gaps, inconsistencies, and recommendations (2019). https://www.hhs.gov/ash/advisory-committees/pain/reports/index.html

- Drug Enforcement Administration, Diversion Control Division . Schedules of controlled substances: rescheduling of buprenorphine from Schedule V to Schedule III. (2002). https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/fed_regs/rules/2002/fr1007.htm

- United States National Library of Medicine . Single dose crossover study to compare the respiratory drive after administration of belbuca, oxycodone and placebo. (2019). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03996694?term=NCT03996694&rank=1

- Preuss CV , KalavaA , KingKC. Prescription of controlled substances: benefits and risks. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island FL, USA (2019). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537318/

- United States Department of Health and Human Services . HHS guide for clinicians on the appropriate dosage reduction or discontinuation of long-term opioid analgesics. (2019). https://www.hhs.gov/opioids/sites/default/files/2019-10/Dosage_Reduction_Discontinuation.pdf