Abstract

Background: A survey of European Pain Federation 2019 attendees was conducted to identify unmet needs in chronic pain patients. Materials & methods: Four questions were asked focusing on functional impairment in chronic pain, including who are at increased risk and ways to better identify and manage these patients. Results: In total 143 respondents indicated that key issues were lack of knowledge, lack of resources/time to assess and manage chronic pain and lack of sufficient tools to identify patients at risk for functional impairment. Education and training of primary care physicians, simplified guidelines and practical tools for assessment and use of multidisciplinary teams to treat chronic pain were recommended. Conclusion: There are many unmet needs in the management of functional impairment in chronic pain patients.

Lay abstract

Chronic pain is one of the most common and complex conditions. It can lead to disability in some patients and significantly affect their ability to function. Patients with chronic pain often have difficulty performing routine household tasks, working productively, engaging in social activities and sleeping. When individuals seek treatment for chronic pain they should be able to have an honest conversation with their doctor about all of the disabling aspects of their pain and agree on achievable goals of treatment (e.g., the ability to perform routine household chores). We asked a group of delegates attending the European Pain Federation pain congress what they thought may impede doctors’ ability to accurately assess and alleviate functional disability associated with chronic pain. According to these survey respondents, general practitioners (GPs) do not have sufficient knowledge, time or resources to properly manage patients with chronic pain. When asked what would help to improve this situation, the survey respondents suggested more training for GPs, better techniques for assessing disability that focus on measurable indicators of disability, such as activity levels, time off work and sleep quality. They also recommend consulting with a number of different healthcare professionals, including physiotherapists and psychologists, who should work collaboratively with GPs to provide comprehensive, holistic care to patients with chronic pain.

Assessment of functional impairment should be an integral part of chronic pain assessment.

This survey of European Pain Federation 2019 pain congress attendees was conducted to identify unmet needs and potential solutions for the assessment of functional impairment in patients with chronic pain.

A short electronic survey related to chronic pain care was conducted that contained four questions: what are the key issues that cause unresolved functional impairment for so many patients?; what would help identify patients at increased risk of long-term functional impairment earlier?; what metrics might provide early warning signs for patients at increased risk of functional decline? and what recommendations would better identify and manage patients with functional decline to avoid significant impact on quality of life?

The most important issues leading to functional impairment were lack of knowledge about how to manage chronic pain in primary care, lack of resources/time to assess and manage chronic pain in primary care, and lack of sufficient tools to identify patients at risk of functional impairment in primary care.

Training for primary care physicians was the top recommendation for identifying patients at risk of functional impairment.

‘Hard’ clinical metrics (standardized scales) to identify patients at risk of functional impairment were preferred by 45% of respondents, and ‘soft’ metrics (nonstandardized measures of symptoms) were preferred by 41%.

The top recommendation for better identification and management of early functional decline was multidisciplinary care involving primary care physicians, psychologists and physiotherapists.

Effective management of chronic pain patients requires more education and training for primary care physicians, as well as simplified guidelines and practical tools for assessment and continuous evaluation of functionality and a multidisciplinary approach to patient care.

Chronic pain, temporally defined as pain that persists for longer than 3 months [Citation1], is a common, complex and potentially disabling condition that affects individuals and society worldwide [Citation2]. Globally, chronic pain conditions, such as low back pain and headache disorders, are leading causes of disability, responsible for more years lived with disability than other chronic diseases, including diabetes and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [Citation3]. Although prevalence varies between countries, estimates suggest that between 10 and 50% of the general population have chronic pain [Citation2,Citation4–8] and between 8 and 14% experience disabling chronic pain that interferes with their daily activities [Citation4,Citation9]. In the UK alone, it was recently estimated that approximately 28 million people (43% of the general population) have chronic pain, with 10–14% of the population reporting moderately or severely limiting chronic pain [Citation6]. Chronic pain can affect people of any age, including children and adolescents, but becomes more common with age as people develop multiple comorbidities, so the prevalence of chronic pain is likely to increase in line with aging populations [Citation7,Citation10–12]. Chronic pain patients with multiple comorbidities and vulnerable social status are at an increased risk of disability [Citation13].

Persistent pain has significant consequences for patients, disrupting sleep, impairing executive function, including attention and memory, impacting their psychological well-being, as evidenced by a higher prevalence of depression and anxiety among patients with chronic pain and generally reducing their ability to work, socialize and participate in daily life activities [Citation9,Citation14–18]. The combination of pain intensity, pain-related distress and functional impairment (interference with activities of daily life and participation in social roles) can have a significant impact on patients’ quality of life [Citation1,Citation19–21].

Unfortunately, few patients with chronic pain are able to achieve complete freedom from pain [Citation22,Citation23], resulting in a high rate of dissatisfaction with care [Citation5,Citation24]. Realistic goal setting is therefore essential before initiating treatment [Citation25–27]. Measurement of pain intensity is an important component of chronic pain assessment, but in the absence of pain biomarkers, it is difficult to assess and currently relies on subjective self-report [Citation28–30].

Pain per se is only one aspect of the patient’s overall experience, and there is increasing recognition that a reduction in pain intensity should not be the only treatment goal [Citation25,Citation31,Citation32]. The impact of chronic pain on psychosocial and functional aspects, such as mood, sleep and the ability to undertake daily activities, are often at least as important to patients as the intensity of the pain itself [Citation32,Citation33]. Patients may also increase their activity levels in response to reduced pain intensity until pain returns to the starting point, thus presenting with unchanged pain intensity but increased functionality (or vice versa). Effective goal setting requires open communication between the patient and physician and patient – healthcare professional (HCP) agreement on achievable, measurable personal goals that focus on functional outcomes, such as the ability to go for short walks or do household chores [Citation25–27,Citation32,Citation34].

The WHO has defined a comprehensive framework for the classification of functioning, disability and health known as the ICF, and endorses functional outcomes as an important determinant of patients’ overall well-being [Citation35]. However, there is currently an unmet need for a brief standardized way to assess functional impairment in patients with chronic pain. The aim of the current qualitative study was to identify current unmet needs and potential solutions for the pro-active assessment of functional impairment in patients with chronic pain, by surveying attendees at the European Pain Federation (EFIC) Congress 2019 on their views about these issues.

Materials & methods

Delegates attending the 11th Congress of the European Pain Federation EFIC ‘Pain in Europe XI’ in Valencia, Spain, between 4 and 7 September 2019 had the opportunity to complete a short electronic survey on the management of patients with chronic pain. The survey was conducted in English and presented on iPads, which were available at the Grünenthal booth. All physicians who took an interest in the survey, either spontaneously or after having been shown it, were invited to participate. No incentives to complete the survey were offered.

This survey did not require institutional review board approval because this survey gathered physician practice related information and did not involve any data either from human participant or animals. This article does not contain any data generated from studies with human participants or animals.

The survey was not designed to inform clinical investigations, but rather to gather insights and understand the physicians’ perceptions and attitudes toward functional impairment in patients with chronic pain. The survey contained four questions (see Supplementary Appendix in Supplementary Materials), designed to gain insight into the issues that exist within pain care that lead to many patients having unresolved functional impairment, how functional impairment can be better identified and which parameters would help physicians to identify patients at risk of functional decline.

For the first two questions, delegates were asked to rate a range of issues/factors on a 7-point Likert scale. Specifically, question 1 asked ‘What issues exist with pain care currently that lead to so many patients suffering unresolved functional impairment?’ and provided a range of possible answers that delegates were asked to rate on a scale from 1 (not an issue) to 7 (major issue). Question 2 asked ‘What would help to identify patients at increased risk of long term functional impairment earlier in their treatment journey?’ and provided a range of possible issues that delegates were asked to rate on a scale from 1 (not helpful) to 7 (very helpful). A free text field was also provided for delegates to highlight any additional issues that they considered important.

Questions 3 and 4 were open-ended. Delegates were asked ‘Are there any metrics that might provide an early warning sign for patients at increased risk of functional decline?’ (question 3) and ‘What recommendations would you make for clinical assessments that may help better identify patients who are showing signs of functional decline to avoid significant impact on quality of life?’ (question 4).

Statistical analysis

Results were analyzed using descriptive statistics (frequency and percentages or means), which were calculated using Excel; no formal statistical analysis was undertaken. Data are available on request from Grünenthal; however, all data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article/as supplementary information files.

Items listed in questions 1 and 2 were ranked according to the proportions of respondents rating each issue with the two highest scores on the Likert scale (6 or 7); therefore, items with the same mean score could have different rankings.

Results

Respondents

A total of 143 EFIC delegates completed the survey: 77 from Latin America (Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador, Honduras, Mexico and Panama), 46 from western Europe (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Italy, The Netherlands, Portugal, San Marino, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK) and 20 from the rest of the world (Algeria, Bangladesh, Bulgaria, Croatia, Hong Kong, Hungary, Israel, Poland, Russia, Serbia, Slovenia, Turkey and Ukraine).

Care issues associated with functional impairment in chronic pain (question 1)

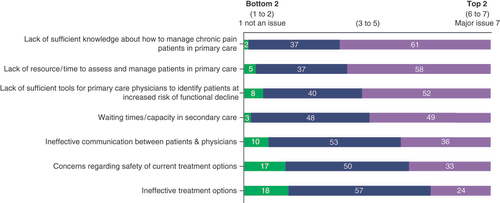

All survey respondents answered this question (n = 143). Based on proportions of respondents choosing a score of 6 or 7 on the 7-point Likert scale, the three most important pain care issues that lead to functional impairment in chronic patients were: lack of sufficient knowledge about how to manage chronic pain patients in primary care (mean score 5.7); lack of resources/time in primary care to assess and manage chronic pain patients in primary care (mean 5.5) and lack of sufficient tools for primary care physicians to identify patients at risk of functional decline (mean 5.3) (). Waiting times/capacity in secondary care also achieved a mean score of 5.3, but compared with a lack of sufficient tools in primary care, slightly fewer respondents (49 vs 52%) scored this issue with 6–7 points and more (48 vs 40%) scored this issue 3–5. Other issues ranked as less important were ineffective communication between patients and physicians (mean score 4.9), concerns about the safety of current treatment options (mean 4.5) and ineffective treatment options (mean 4.3).

Green indicates scores of 1 or 2, blue for scores of 3–5, and purple for scores of 6 or 7.

Regions differed in their rankings of the most important issues (). In western Europe, the top four issues were: lack of resources/time in primary care to assess and manage chronic pain patients (mean 5.6); lack of sufficient knowledge about how to manage chronic pain patients in primary care (mean score 5.3); lack of sufficient tools for primary care physicians to identify patients at risk of functional decline (mean 5.0) and ineffective communication between patients and physicians (mean 5.0) (Supplementary Figure 1A). In Latin America, the top four issues in order were: lack of sufficient knowledge about how to manage chronic pain patients in primary care (mean score 5.9); waiting times in secondary care (mean 5.5); lack of resources/time in primary care to assess and manage chronic pain patients (mean 5.4) and lack of sufficient tools for primary care physicians to identify patients at risk of functional decline (mean 5.4) (Supplementary Figure 1B). In the rest of the world, the top four issues in order were: lack of resources/time in primary care to assess and manage chronic pain patients (mean 6.0); lack of sufficient knowledge about how to manage chronic pain patients in primary care (mean score 5.5); waiting times in secondary care (mean 5.5) and lack of sufficient tools for primary care physicians to identify patients at risk of functional decline (mean 5.5) (Supplementary Figure 1C).

Table 1. Rankings, overall and by region, for responses to question 1: what are the key issues leading to a high proportion of chronic pain patients experiencing functional impairment?

Several additional issues were raised by respondents from specific countries or regions. Out-of-pocket expenses required for secondary care and the high cost of alternative treatments for pain were highlighted by Austrian and Israeli respondents, respectively. Latin American respondents noted lack of availability and high cost of some treatments, as well as lack of educational tools and excessive regulations.

Tools for identification of patients at risk of functional impairment (question 2)

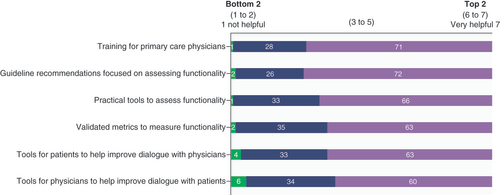

All survey respondents answered this question (n = 143). Based on proportions of high scores, the three most helpful tools for identifying chronic pain patients at risk of functional impairment were: training for primary care physicians (mean score 6.0); guidelines focused on assessing functionality (mean 5.9) and practical tools to assess functionality (mean 5.7) (). Validated metrics also achieved a mean score of 5.7, but compared with practical tools to assess functionality, fewer respondents (63 vs 66%) scored this issue with 6–7 points and more (35 vs 33%) scored this issue 3–5. Other items ranked as less helpful were tools for patients to help them improve dialogue with their physician(s) (mean 5.5) and tools for physicians to help them improve dialogue with their patients (mean 5.5).

Green indicates scores of 1 or 2, blue for scores of 3–5 and purple for scores of 6 or 7.

Regions were generally consistent in their ratings for these factors ( and Supplementary Figures 2A–C). Training for primary care physicians was ranked highest in importance in all regions. The top four issues were the same in Latin America and the rest of the world, albeit in a slightly different order. The major regional difference was that, in Europe, validated metrics and practical tools to measure functionality were rated sixth and third, respectively, whereas these were rated third and fourth, respectively, in Latin America and second and third, respectively, in the rest of the world.

Table 2. Rankings, overall and by region, for responses to question 2: what would help to identify chronic pain patients at increased risk of long-term functional impairment?

Other issues related to identifying patients at increased risk of long-term functional impairment raised by delegates from specific countries were a lack of postgraduate education on how to examine patients with pain for primary care physicians (Austria), the need for clear guidelines to identify patients at risk of long-term functional impairment (Ecuador) and more time for consultations (Israel).

Metrics to identify patients at risk of functional impairment (question 3)

Ninety-four survey respondents answered this question (65.7%). Respondents provided a range of possible metrics for identifying patients at risk of functional impairment, and these could be grouped according to whether they were ‘hard’ assessments (standardized/validated scales or metrics used in the measurement of pain, functionality, or associated comorbidities) or ‘soft’ assessments (nonstandardized measures of symptoms, the level of pain or functionality).

Hard assessments were preferred by 42 respondents (45%). These respondents recommended one hard metric only, two hard metrics only, two hard metrics and one soft assessment or three hard metrics. 39 respondents (41%) had a preference for soft assessments, as indicated by a recommendation for one soft metric only, two soft metrics only, two soft metrics and one hard assessment or three soft metrics. The remaining respondents had no preference (they recommended one hard metric and one soft metric or no metrics).

The respondents’ recommendations are summarized in . In addition to visual analogue scales and psychological assessments, recommended hard assessments included measures of health status (e.g., Short Form-36), pain (e.g., Douleur Neuropathique 4 [DN4], Brief Pain Inventory, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities [WOMAC] Osteoarthritis Index, quantitative sensory testing), functional capacity (e.g., 6-min walk test [6MWT], Karnofsky Performance Scale) and disability (e.g., Oswestry Disability Index, Functional Independence Measure). The four most important ‘soft’ assessments, as suggested by >10% of respondents, were metrics related to activity level/capacity/functionality, pain, time off work and sleep. Measures of activity level, physical capacity and functionality included range of motion assessment, movement tracking (e.g. via fitness tracker), ability to dress unaided, ability to climb stairs, and ability to cook a meal. Pain-related warnings of functional decline included pain attacks, worsening pain or breakthrough pain. Time off work included ability to work, sick leave and absences from work. Sleep-related metrics included sleep quality, ability to sleep and sleep tracking via fitness tracking devices.

Table 3. Responses to question 3: which metrics might provide an early warning sign for patients at increased risk of functional decline?

Recommendations for how to identify & manage with early signs of functional decline (question 4)

9232 survey respondents answered this question (64.3%). A number of themes emerged from the free text answers to this question. A multidisciplinary approach to care, involving primary care physicians, psychologists and physiotherapists, was the most frequently recommended approach to identify and manage patients at risk of functional decline, followed by use of validated scales/assessment tools, including a simple screening tool that could be used in primary care, and a basic measure of function that could be repeated over time to detect change. Effective communication between physicians and patients, with physicians being alert to and actively asking about changes in patients’ activities/daily lives in addition to their clinical status, was also identified as important for successful management of patients with chronic pain. Respondents also acknowledged the need for training for primary care physicians, support and education for patients and earlier referral to appropriate specialist care.

Discussion

Our study among international EFIC delegates suggests that primary care physicians lack the knowledge, time and practical tools to recognize and assess functional impairment in patients with chronic pain. There could be an inherent selection bias with the HCPs who participated in the survey, as they are obviously interested in this topic and as a consequence may have a better understanding and knowledge that may lead to better management of their patients. Our data also show that, while many tools exist for assessing functionality in chronic pain patients, there is little consensus among HCPs involved in pain management about how best to approach functionality assessment. This suggests that there is a need for guidelines focused and a simple tool to assess functionality. Such a tool should assess the impact of pain on the patient’s ability to perform routine daily activities, work and sleep.

To our knowledge, our survey is the first multinational survey of HCPs interested in pain management regarding their views on the assessment of functional impairment in patients with chronic pain. The respondents’ impressions of unmet needs in primary care are consistent with previous research about lack of knowledge and assessment time and tools in chronic pain management [Citation36]. Patients with chronic low back pain have reported that their primary care physicians had a cursory or superficial approach to the pain management and expressed concern about restricted consultation times [Citation24]. Although our survey respondents viewed ineffective physician–patient communication as less important than other perceived inadequacies of primary care, this highlights the importance of effective communication between physicians and patients with chronic pain to ensure patient–physician agreement about the goals of care and expectations of treatment [Citation25–27,Citation32–34,Citation37]. If, for example, patients prioritize reducing pain intensity while physicians are focused on improving function, there is potential for mistrust and dissatisfaction with care [Citation32]. In a study from Germany, the most important concerns of patients with osteoarthritis were pain and disability, whereas primary care physicians focused on disease pathology and treatments options, but spent little time addressing the patient’s fears [Citation38]. HCPs also often underestimate the patient’s pain severity or the impact of pain on the patient’s ability to undertake normal daily activities [Citation39].

Researchers have highlighted gaps in undergraduate medical training on pain assessment and management, particularly the psychosocial aspects of chronic pain [Citation40–43]. In US surveys, more than 90% of primary care physicians reported finding chronic pain difficult to manage [Citation20] and 66% felt that their training in chronic care was inadequate [Citation44]. Primary care physicians report that they often struggle to manage their complex medical and psychosocial needs of patients with chronic pain, especially within the time available for consultations [Citation29]. Therefore, many HCPs feel underprepared to manage chronic pain [Citation45]. Yet, only a minority of patients with chronic pain are referred to a pain specialist, the supply of which is greatly outstripped by demand [Citation16,Citation36,Citation46,Citation47]. This suggests that patients are referred only at a late stage of chronic pain [Citation47], when primary care physicians have exhausted all their available tools for pain management. As well as the requirement for earlier specialist referral, our survey respondents identified a need to improve core competencies in pain management for primary care practitioners. This could potentially be achieved by providing comprehensive pain management education to medical students, with pain-specific competencies included as a component for practice entry requirements [Citation36,Citation48,Citation49].

Primary care physicians see patients with chronic pain longitudinally over time [Citation50], so are well placed to recognize functional deterioration. However, as is evident from our survey results, their ability to formally assess functional deterioration is hampered by insufficient pain education [Citation36] and lack of consensus on how to address the patients’ overall function (physical and psychosocial) using standardized assessment tools [Citation51].

We also noted a lower response rate to the question about assessment tools (question 3) than to earlier questions in our survey. This probably reflects some uncertainty of recognizing and understanding functional impairment in our survey respondents, who identified numerous validated tools to assess functional impairment () [Citation52–54], but showed no consensus on which assessment to use. None of the available tools incorporates all of the functional domains that physicians in this survey identified as relevant, including interference with the ability to perform activities of daily living, work and sleep. Therefore, in addition to validated tools, a need for practical tools incorporating these domains of functionality was identified, as was a need for guidelines focused on assessing functionality.

Our survey results also emphasize the importance of multidisciplinary care, which facilitates improvements in functional capacity in patients with chronic pain [Citation55–58]. The structure of multidisciplinary teams varies, but the core team generally includes a group of physicians (e.g., a primary care physicians, pain specialists, and psychiatrists) and nonphysicians (e.g., psychologists, physiotherapists and nurses) [Citation59]. Together, the multidisciplinary team should assess and manage the physical and psychosocial aspects of chronic pain, with therapy tailored to the individual needs of the patient [Citation58,Citation59]. However, data show that attitudes/beliefs about pain differ between HCPs working in a rehabilitative setting compared with a community or hospital setting [Citation60]. Regardless of the setting for chronic pain care, all members of the multidisciplinary team need to ensure they understand which outcomes are most important to patients in order to provide the best possible care [Citation60]. Whereas members of the healthcare team are likely to prioritize improving the patient’s functional status, each patient has different priorities, with many patients focused on reducing pain intensity [Citation32,Citation55,Citation61]. As also indicated by our survey, effective physician–patient communication should enable a better understanding of each patient’s level of functional impairment, and patient education initiatives should help to narrow any gaps between patient expectations and achievable functional goals of therapy [Citation32].

Our study had several limitations, some of which stemmed from the small-scale nature of the survey (143 respondents) and the source of the respondents being individuals attending an international pain congress, which may have led to potential selection and response bias. The majority of respondents were from Latin America (54%), with only 32% of respondents from western European countries and the remainder from other countries, including Eastern European countries, which did not reflect the overall regional makeup of the EFIC Congress. This selection bias, with a preponderance of respondents from Latin American countries, could in turn have contributed to response bias, with respondents from less developed countries potentially having different experiences and opinions to those from wealthier western European countries. Our survey did not ask for specific information about each respondent, other than the country they were from, so we cannot compare responses between different HCPs. We have assumed that, because they were attending the EFIC conference, their predominant area of specialist interest was pain, but our cohort may have included rehabilitation specialists, rheumatologists, anesthetists, physical therapists and nurses.

The questionnaire was not validated, and the first two questions provided respondents with a series of proposed issues/factors that may have biased the results toward particular themes, such as inadequacies of primary care, compared with questions 3 and 4, which were open-ended questions and identified other priorities such as the multidisciplinary management of chronic pain and effective physician–patient communication. In addition, the questionnaire did not include a question about whether the respondents considered physical impairment to be an issue, thereby guiding their responses toward this conclusion.

In all three regions (western Europe, Latin America, and the rest of world), the most important issues in response to question 1 (‘What issues exist with pain care currently that lead to so many patients suffering unresolved functional impairment?’) were lack of resources/time to assess and manage chronic pain in primary care, lack of sufficient knowledge about how to manage chronic pain in primary care and lack of sufficient tools for primary care physicians to identify patients at risk of functional impairment. However, waiting times in secondary care was identified as a top four issue in Latin America and the rest of the world (2 and 3, respectively), but not in western Europe, where ineffective patient–physician communication ranked higher than waiting times (4 and 5, respectively). This difference may reflect disparities in the availability of pain specialists between regions. In response to question 2 (‘What would help to identify patients at increased risk of long-term functional impairment earlier in their treatment journey?’), respondents from all regions ranked training for primary care physicians as most important. Specialists probably see chronic pain patients who cannot be managed effectively in primary care [Citation50] or may have a generally negative view of primary care [Citation62], which may bias their thinking against the competence of primary care physicians. Research shows that primary care physicians have a more positive view of their relationship with specialists than specialists of their relationship with primary care physicians [Citation63]. These attitudes could have contributed to the top answers to questions 1 and 2 being related to lack of knowledge, resources or tools in primary care.

Conclusion

There are a number of unmet needs in the management of functional impairment in patients with chronic pain, the key one is better education of primary care physicians in the assessment and management of chronic pain. Additional unmet needs are the facilitation of better assessment of chronic pain-related functional impairment and a shift toward setting objectives for restoring or maintaining functional goals in chronic pain management. The pain congress attendees who participated in the survey recommended the provision of more training for primary care physicians, practical tools for assessing functional impairment over time, guidelines focused on assessing and continuous evaluation of functionality, and better access to secondary care and multidisciplinary teams including physiotherapist, psychologist and pain specialist that can provide a holistic approach to chronic pain management.

Author contributions

R Karra was involved in the concept, design, and implementation of the survey, as well as data collection and interpretation. SH Rossing was involved in delegate enrollment. D Mohammed was involved in data analysis. OC Namnún and M Heine were involved in manuscript development. L Parmeggiani and all other authors critically assessed and reviewed all drafts of the manuscript and approved the manuscript for submission. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Ethical conduct of research

This survey did not require institutional review board approval because this survey gathered physician practice related information and did not involve any data either from human participant or animals. This article does not contain any data generated from studies with human participants or animals.

Supplemental Document 1

Download MS Word (269.1 KB)Acknowledgments

We would like thank Carlos Garcia Fernandez of Grünenthal for reviewing the manuscript.

Supplementary data

To view the supplementary data that accompany this paper please visit the journal website at: www.tandfonline.com/doi/suppl/10.2217/pmt-2020-0098

Financial & competing interests disclosure

All authors are employees of Grünenthal. The survey and the journal’s Accelerate Publication fee were funded by Grünenthal. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Medical writing assistance was provided by Catherine Rees of Springer Healthcare Communications who wrote the outline and Joanne Dalton who wrote the first draft on behalf of Springer Healthcare Communications and was funded by Grünenthal.

Data sharing statement

Data are available on request from Grünenthal. However, all data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article/as supplementary information files.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Treede RD , RiefW , BarkeAet al. Chronic pain as a symptom or a disease: the IASP Classification of Chronic Pain for the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). Pain160(1), 19–27 (2019).

- Goldberg DS , McGeeSJ. Pain as a global public health priority. BMC Public Health11, 770 (2011).

- GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators . Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet392(10159), 1789–1858 (2018).

- Dahlhamer J , LucasJ , ZelayaCet al. Prevalence of chronic pain and high-impact chronic pain among adults - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep.67(36), 1001–1006 (2018).

- de Souza JB , GrossmannE , PerissinottiDMN , deOliveira Junior JO , da FonsecaPRB , PossoIP. Prevalence of chronic pain, treatments, perception, and interference on life activities: brazilian population-based survey. Pain. Res. Manag.2017, 4643830 (2017).

- Fayaz A , CroftP , LangfordRM , DonaldsonLJ , JonesGT. Prevalence of chronic pain in the UK: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population studies. BMJ. Open.6(6), e010364 (2016).

- Mills SEE , NicolsonKP , SmithBH. Chronic pain: a review of its epidemiology and associated factors in population-based studies. Br. J. Anaesth.123(2), e273–e283 (2019).

- Sa KN , MoreiraL , BaptistaAFet al. Prevalence of chronic pain in developing countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Rep.4(6), e779 (2019).

- May C , BrcicV , LauB. Characteristics and complexity of chronic pain patients referred to a community-based multidisciplinary chronic pain clinic. Can. J. Pain.2(1), 125–134 (2018).

- Logan DE , SimonsLE , SteinMJ , ChastainL. School impairment in adolescents with chronic pain. J. Pain9(5), 407–416 (2008).

- US Food and Drug Administration . Patient-focused drug development meeting on chronic pain. (2018). https://www.fda.gov/media/114758/download

- Zanocchi M , MaeroB , NicolaEet al. Chronic pain in a sample of nursing home residents: prevalence, characteristics, influence on quality of life (QoL). Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr.47(1), 121–128 (2008).

- Cabrera-Leon A , Cantero-BraojosMA , Garcia-FernandezL , Guerrade Hoyos JA. Living with disabling chronic pain: results from a face-to-face cross-sectional population-based study. BMJ Open8(11), e020913 (2018).

- Bair MJ , WuJ , DamushTM , SutherlandJM , KroenkeK. Association of depression and anxiety alone and in combination with chronic musculoskeletal pain in primary care patients. Psychosom. Med.70(8), 890–897 (2008).

- Berryman C , StantonTR , BoweringKJ , TaborA , McFarlaneA , MoseleyGL. Do people with chronic pain have impaired executive function? A meta-analytical review. Clin. Psychol. Rev.34(7), 563–579 (2014).

- Breivik H , CollettB , VentafriddaV , CohenR , GallacherD. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur. J. Pain.10(4), 287–333 (2006).

- Jank R , GalleeA , BoeckleM , FieglS , PiehC. Chronic pain and sleep disorders in primary care. Pain Res. Treat.2017, 9081802 (2017).

- Kroenke K , OutcaltS , KrebsEet al. Association between anxiety, health-related quality of life and functional impairment in primary care patients with chronic pain. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry.35(4), 359–365 (2013).

- Duenas M , OjedaB , SalazarA , MicoJA , FaildeI. A review of chronic pain impact on patients, their social environment and the health care system. J. Pain. Res.9, 457–467 (2016).

- McCarberg BH , NicholsonBD , ToddKH , PalmerT , PenlesL. The impact of pain on quality of life and the unmet needs of pain management: results from pain sufferers and physicians participating in an Internet survey. Am. J. Ther.15(4), 312–320 (2008).

- Wahl AK , RustoenT , RokneBet al. The complexity of the relationship between chronic pain and quality of life: a study of the general Norwegian population. Qual. Life Res.18(8), 971–980 (2009).

- Marcus DA . Managing chronic pain in the primary care setting. Am. Fam. Physician66(1), 36–42 (2002).

- Gureje O , SimonGE , Von KorffM. A cross-national study of the course of persistent pain in primary care. Pain92(1–2), 195–200 (2001).

- Chou L , RangerTA , PeirisWet al. Patients’ perceived needs for medical services for non-specific low back pain: a systematic scoping review. PLoS ONE13(11), e0204885 (2018).

- Dowell D , HaegerichTM , ChouR. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain--United States, 2016. JAMA315(15), 1624–1645 (2016).

- Filoramo MA . Improving goal setting and goal attainment in patients with chronic noncancer pain. Pain. Manag. Nurs.8(2), 96–101 (2007).

- Mills S , TorranceN , SmithBH. Identification and management of chronic pain in primary care: a review. Curr. Psychiatry Rep.18(2), 22 (2016).

- Fillingim RB , LoeserJD , BaronR , EdwardsRR. Assessment of chronic pain: domains, methods, and mechanisms. J. Pain17(Suppl. 9), T10–20 (2016).

- Webster F , RiceK , KatzJ , BhattacharyyaO , DaleC , UpshurR. An ethnography of chronic pain management in primary care: the social organization of physicians’ work in the midst of the opioid crisis. PLoS ONE14(5), e0215148 (2019).

- Xu X , HuangY. Objective pain assessment: a key for the management of chronic pain. F1000Res9, (2020).

- Ballantyne JC , SullivanMD. Intensity of chronic pain--the wrong metric?N. Engl. J. Med.373(22), 2098–2099 (2015).

- Henry SG , BellRA , FentonJJ , KravitzRL. Goals of chronic pain management: do patients and primary care physicians agree and does it matter?Clin. J. Pain33(11), 955–961 (2017).

- Geurts JW , WillemsPC , LockwoodC , van KleefM , KleijnenJ , DirksenC. Patient expectations for management of chronic non-cancer pain: a systematic review. Health Expect.20(6), 1201–1217 (2017).

- Constantino RC . Setting realistic goals for patients with chronic pain. Pharmacy Today23(9), 45 (2017).

- World Health Organization . International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). (2018). www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/

- Dubois MY , FollettKA. Pain medicine: the case for an independent medical specialty and training programs. Acad. Med.89(6), 863–868 (2014).

- Alami S , BoutronI , DesjeuxDet al. Patients’ and practitioners’ views of knee osteoarthritis and its management: a qualitative interview study. PLoS ONE6(5), e19634 (2011).

- Rosemann T , WensingM , JoestK , BackenstrassM , MahlerC , SzecsenyiJ. Problems and needs for improving primary care of osteoarthritis patients: the views of patients, general practitioners and practice nurses. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord.7, 48 (2006).

- Toye F , JenkinsS. ‘It makes you think’ – exploring the impact of qualitative films on pain clinicians. Br. J. Pain.9(1), 65–69 (2015).

- Loeser JD , SchatmanME. Chronic pain management in medical education: a disastrous omission. Postgrad. Med.129(3), 332–335 (2017).

- Rice K , RyuJE , WhiteheadC , KatzJ , WebsterF. Medical trainees’ experiences of treating people with chronic pain: a lost opportunity for medical education. Acad. Med.93(5), 775–780 (2018).

- Yanni LM , McKinney-KetchumJL , HarringtonSBet al. Preparation, confidence, and attitudes about chronic noncancer pain in graduate medical education. J. Grad. Med. Educ.2(2), 260–268 (2010).

- Nasser SC , NassifJG , SaadAH. Physicians’ attitudes to clinical pain management and education: survey from a Middle Eastern country. Pain. Res. Manag.2016, 1358593 (2016).

- Darer JD , HwangW , PhamHH , BassEB , AndersonG. More training needed in chronic care: a survey of US physicians. Acad. Med.79(6), 541–548 (2004).

- Egerton T , DiamondLE , BuchbinderR , BennellKL , SladeSC. A systematic review and evidence synthesis of qualitative studies to identify primary care clinicians’ barriers and enablers to the management of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage25(5), 625–638 (2017).

- Harden N , CohenM. Unmet needs in the management of neuropathic pain. J. Pain Symptom Manag.25(Suppl. 5), S12–S17 (2003).

- Triva P , JukicM , PuljakL. Access to public healthcare services and waiting times for patients with chronic nonmalignant pain: feedback from a tertiary pain clinic. Acta. Clin. Croat.52(1), 79–85 (2013).

- Hogans BB , Watt-WatsonJ , WilkinsonP , CarrECJ , GordonDB. Perspective: update on pain education. Pain159(9), 1681–1682 (2018).

- Shipton EE , BateF , GarrickR , SteketeeC , ShiptonEA , VisserEJ. Systematic review of pain medicine content, teaching, and assessment in medical school curricula internationally. Pain Ther.7(2), 139–161 (2018).

- Starfield B . Is primary care essential?Lancet344(8930), 1129–1133 (1994).

- Zidarov D , ViscaR , AhmedS. Type of clinical outcomes used by healthcare professionals to evaluate health-related quality of life domains to inform clinical decision making for chronic pain management. Qual. Life Res.28(10), 2761–2771 (2019).

- Bendinger T , PlunkettN. Measurement in pain medicine. BJA Educ.16(9), 310–315 (2016).

- Dansie EJ , TurkDC. Assessment of patients with chronic pain. Br. J. Anaesth.111(1), 19–25 (2013).

- Turk DC , FillingimRB , OhrbachR , PatelKV. Assessment of psychosocial and functional impact of chronic pain. J. Pain17(Suppl. 9), T21–T49 (2016).

- Fedoroff IC , BlackwellE , SpeedB. Evaluation of group and individual change in a multidisciplinary pain management program. Clin. J. Pain30(5), 399–408 (2014).

- Ibrahim ME , WeberK , CourvoisierDS , GenevayS. Recovering the capability to work among patients with chronic low back pain after a four-week, multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation program: 18-month follow-up study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord.20(1), 439 (2019).

- Inoue M , InoueS , IkemotoTet al. The efficacy of a multidisciplinary group program for patients with refractory chronic pain. Pain Res. Manag.19(6), 302–308 (2014).

- Kamper SJ , ApeldoornAT , ChiarottoAet al. Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ350, h444 (2015).

- Pergolizzi J , AhlbeckK , AldingtonDet al. The development of chronic pain: physiological CHANGE necessitates a multidisciplinary approach to treatment. Curr. Med. Res. Opin.29(9), 1127–1135 (2013).

- Rainville J , BagnallD , PhalenL. Health care providers’ attitudes and beliefs about functional impairments and chronic back pain. Clin. J. Pain11(4), 287–295 (1995).

- Artner J , KurzS , CakirB , ReichelH , LattigF. Intensive interdisciplinary outpatient pain management program for chronic back pain: a pilot study. J. Pain Res.5, 209–216 (2012).

- Pena-Dolhun E , GrumbachK , VranizanK , OsmondD , BindmanAB. Unlocking specialists’ attitudes toward primary care gatekeepers. J. Fam. Pract.50(12), 1032–1037 (2001).

- Marshall MN . How well do GPs and hospital consultants work together? A survey of the professional relationship. Fam. Pract.16(1), 33–38 (1999).