Abstract

Aim: To investigate use of the ‘Managing Advanced Cancer Pain Together’ conversation tool between individuals with advanced cancer and healthcare professionals (HCPs) during routine consultations. Methods: Twenty-one patients and six HCPs completed questionnaires before and after use of the tool (at their routine consultation 1 and consecutive consultation 2, respectively). Results: Patients and HCPs were satisfied with communication during both consultations. When using the tool, patients most frequently selected physical pain descriptors (95.2%), followed by emotional (81.0%), social (28.6%) and spiritual (28.6%) descriptors. Patients found the tool useful, stating that it helped them describe their pain. HCPs considered the tool difficult to incorporate into consultations. Conclusion: The study highlighted the need to consider the various aspects of cancer pain.

Lay abstract

The Managing Advanced Cancer Pain Together conversation tool was designed to help patients with advanced cancer and their healthcare professionals (HCPs) discuss various aspects of pain (physical, emotional, social and spiritual pain) during their consultations. The tool comprises 41 words to describe pain, and patients are asked to select three words that best describe their experience. For this study, patients with advanced cancer and their HCPs completed two consultations, one without the tool and one with the tool. Overall, patients found the tool helpful and used words relating to physical (95.2%), emotional (81.0%), social (28.6%) and spiritual (28.6%) pain to describe their recent experience. HCPs reported that the tool may be difficult to use during consultation due to limited time.

Pain has a substantial negative effect on the quality of life of individuals with cancer. Although reports vary, pain is particularly prevalent for individuals with multiple myeloma (up to 90%) [Citation1], breast cancer (74%) [Citation2], prostate cancer (up to 70%) [Citation3], lung cancer (47%) [Citation4] and generally in advanced forms of cancer [Citation5]. Thus the management of pain, from onset through to long-term survivorship or end-of-life care, has emerged as a priority in oncology care [Citation6].

Barriers to pain management include individuals’ attitudes or behavior toward pain, varying knowledge and attitudes among healthcare professionals (HCPs) toward pain management, and inadequate communication between individuals with cancer and HCPs [Citation7]. Importantly, some HCPs rely on their own observations rather than asking the individual, thus not considering the individual’s ‘total pain’ experience [Citation8–10]. Total pain is an important concept, acknowledging the multidimensional nature of pain which includes the physical, emotional, social and spiritual aspects [Citation10–12]. The contribution of each aspect will vary between individuals and can strongly influence their experience of pain [Citation13,Citation14]. It has also been recognized that the holistic nature of pain contributes to pain management barriers across the world [Citation13]. The challenge of treating patients’ total pain is often exacerbated by their difficulty in distinguishing and expressing which aspect(s) of pain they are experiencing [Citation11]. The consideration of total pain is particularly important in cancer, where the sensory components of pain may be less important to individuals than the evaluative/emotional aspects [Citation15,Citation16]. As such, a more holistic pain discussion between individuals with cancer and their HCP could enhance success in the management of pain. Despite this, there has been a relatively limited number of articles published on the topic since the concept of total pain was introduced in the 1960s [Citation12,Citation13].

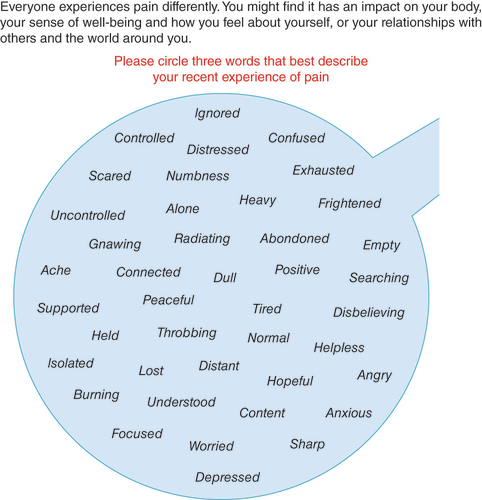

The Managing Advanced Cancer Pain Together (MACPT) team (http://macpt.info/), a multi-professional group of cancer pain management specialists from France, Germany, Belgium and the UK, have drawn upon their experience and current best practice guidelines to develop a simple paper-based conversation tool designed to facilitate a comprehensive pain dialogue, acknowledging the multidimensional nature of pain, between individuals with cancer and their HCPs in routine clinical practice () [Citation17,Citation18]. The input of patients, as well as of individuals who had been bereaved, was also obtained during development of the tool; further detail on the development process has been published elsewhere [Citation17,Citation18]. The MACPT conversation tool consists of 41 terms to help describe the individual’s experience of pain. Each term can be mapped to one or more predefined categories of pain: physical (e.g., ‘ache’), emotional (e.g., ‘heavy’), social (e.g., ‘supported’) and spiritual pain (e.g., ‘helpless’) (see Supplementary Material 1 for further information). The HCP asks the individual to select the three words that best describe their recent experience of pain and encourages the individual to explain their choices in more detail during their consultation to support a more holistic pain dialogue. Given the limited time available during standard-of-care (SoC) consultations, having patients choose only three words encourages them to be selective and focus discussions on the most important aspects of their pain experience. It should be noted that the MACPT conversation tool is not intended to be used as a measurement of pain, but to facilitate communication during SoC consultations. The overall aim of this study was to investigate use of the MACPT conversation tool in routine face-to-face SoC consultations. Specifically, the primary objective of the study was to investigate the impact of the MACPT conversation tool on overall satisfaction with communication during SoC consultations from the perspective of individuals with advanced cancer and HCPs. Further objectives included investigating the impact of the MACPT conversation tool on satisfaction with specific aspects of the conversation from the perspective of individuals with advanced cancer and HCPs, exploring the individuals’ recent experience of total cancer pain, including the words selected to describe their pain on the MACPT tool, the perceived usefulness of the MACPT tool from the individual and HCP perspectives and the perceived closeness of the relationship between the individuals and their HCP (i.e., the patient–HCP relationship).

MACPT conversation tool © MACPT 2016. May be reproduced for use in clinical practice.

Patients & methods

Study design

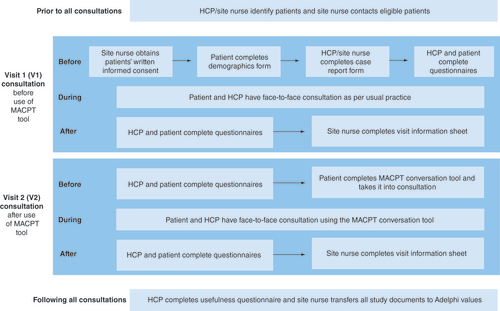

Using a short-term, pre/post study design, the study participants – individuals with advanced cancer (referred to as ‘patients’ hereafter) and their HCPs – completed two study visits, each coinciding with a routine face-to-face SoC consultation. The first study visit (V1) was conducted as per usual practice, and the MACPT conversation tool was used during the second study visit (V2). Patients and their HCPs independently completed various questionnaires at the clinical site before and after the two study visits. It was essential that patients completed both study visits with the same HCP and that V2 took place within 2 months of V1.

Recruitment & procedures

Patients with advanced cancer and their HCPs were recruited from two clinical sites in the UK and one clinical site in France from January 2019 to March 2020. A fourth planned clinical site in Germany did not open to recruitment. Patients were eligible to take part if they were aged 18 years or older; had a diagnosis of advanced cancer, specifically metastatic (stage IV) breast cancer, metastatic (stage IV) prostate cancer, metastatic (stage IIIB/IV) lung cancer or multiple myeloma; were literate with no known visual, auditory or memory impairments; and had sufficient capabilities (as judged by the HCPs) to take part in the study. As the aforementioned types of cancer are most frequently associated with advanced cancer pain, there was no eligibility criterion related to the experience of pain itself. HCPs were eligible to take part if they were a physician or nurse involved in the management of advanced cancer patients for at least 1 year, with no prior exposure to the MACPT conversation tool (i.e., had not seen or used the tool previously) and were available for both study visits. Participants provided written informed consent to participate prior to conducting any study-related activities.

Ethics

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Health and Social Care Research Ethics Committee (HSC REC) and the Health Research Authority in the UK (HSC REC reference: 18/NI/0147), the Comité de Protection des Personnes in France (identification code: 20160376) and the ethics committee at Charité hospital (the German clinical site, identification code: EA4/197/19). Further, the study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and later amendments.

Data collection

Upon enrolment, HCPs completed a paper ‘screener’ form providing information on their demographic characteristics and clinical experience. Patients also completed a paper demographic form, providing information such as age and sex, while HCPs completed a paper case report form for each patient, providing clinical characteristics such as the patient’s primary cancer diagnosis, treatment history and concomitant conditions. These forms were administered by a site nurse, who also completed a visit information sheet to capture information about each visit, such as duration of consultation and whether it was the patient’s first encounter with the consulting HCP.

Before and after both study visits, participants independently completed various questionnaires (see Supplementary Material 2) selected based on the findings of a detailed literature review of existing instruments assessing communication during consultations and the experience and impact of pain. The face, content and psychometric validity of existing instruments, relevant to the study objectives, were assessed to identify the most suitable questionnaires. While a few validated questionnaires were selected for use, two validated questionnaires were modified for the purpose of the study. For the objectives where an appropriate questionnaire was not already available, a new questionnaire was developed (e.g., to investigate the usefulness of the MACPT conversation tool; see Supplementary Material 2 for further information). All questionnaires, as well as the MACPT conversation tool, were then translated from English into French and German for use at the relevant clinical sites. Of note, both forward and backward translations were conducted, and any differences were reconciled; doing so ensured the documents were translated accurately and prevented any challenges with using the questionnaires/conversation tool in different languages. This was of particular importance to ensure the words on the MACPT conversation tool were consistent across the three languages. An overview of the study process, including the timing of questionnaire administration, is outlined in below.

Analysis

This paper presents descriptive results including (but not limited to):

Mean patient- and HCP-reported scores on the Perceived Interpersonal Closeness Scale (PICS) [Citation19] before and after V1 and V2.

Mean patient- and HCP-reported satisfaction scores, both overall and for individual items, on the Patient/Physician Satisfaction Questionnaire [Citation20] at V1 and V2. Overall scores are also adjusted for PICS scores.

Patients’ overall pain experience on a five-point Verbal Rating Scale at V1 and V2, from the patient and HCP perspective.

Mean patient- and HCP-reported ‘pain interference’ scores on the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) [Citation21] at V1 and V2, summarized by level of pain interference (none/mild, moderate and severe) [Citation22].

Frequency and percentage of patients selecting each pain descriptor on the MACPT conversation tool.

Summary of responses on the MACPT usefulness questionnaire from the patient and HCP perspective.

Any missing or incomplete data were not replaced or imputed. For validated questionnaires, including modified versions, data scoring and missing data were handled according to the scoring manual. For the purpose of data analysis, completed questionnaires were translated back into English where necessary, and no challenges were faced in relation to the translated data or using the questionnaires/MACPT conversation tool in various languages more generally.

For further information on the methods used, please visit http://www.encepp.eu/encepp/viewResource.htm?id=39584.

Results

Due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, the study was unfortunately terminated early and therefore the target sample size of 200 patients and 20 HCPs could not be achieved. The early termination of the study also meant that no recruitment took place at the fourth planned clinical site in Germany. Given the substantially reduced sample size, only descriptive results are presented.

Participants’ characteristics

The study sample consisted of six HCPs and 21 patients who completed both V1 and V2 and were all exposed to the MACPT conversation tool before V2. All HCPs who participated in the study were female (100.0%), with a mean age of 41 years, and an equal proportion were from the UK (50.0%) and France (50.0%). Two-thirds of HCPs were physicians (66.7%), one-third were nurses (33.3%), and they had been treating individuals with advanced cancer for a mean of 4.5 years.

Most of the 21 patients were French (85.7%) and female (76.2%), with a mean age of 60 years. The patients’ highest level of education varied from secondary school (19.0%) to postgraduate degrees (9.5%). A high proportion had a primary diagnosis of breast cancer (61.9%) and had lived with cancer for nearly 7 years on average. Of the 19 patients with a solid tumor (90.5%), nearly two-thirds (63.2%) had a current bone metastasis. Further, 57.1% of all patients had experienced a skeletal-related event (bone radiation, bone surgery, pathological fracture or spinal cord compression) within the last 12 months (Supplementary Material 3).

A high proportion of patients had experienced (either in the past or currently) chemotherapy (85.7%), surgery (85.7%) and/or radiotherapy (81.0%). Additionally, 71.4% of patients were receiving strong opioids to treat their pain. The most frequently reported concomitant conditions post-onset of cancer were depression (28.6%) and anxiety (19.0%).

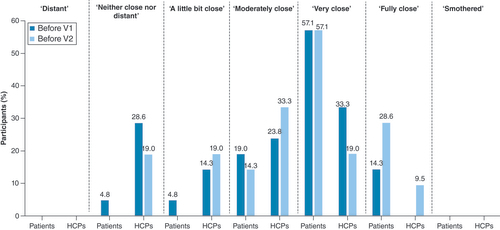

Nearly three-quarters of patients (71.4%) had been under the care of the HCP prior to the study. Patients were seen by the same HCP at both visits, most of which were conducted in hospital-based outpatient settings (V1: 71.4%; V2: 76.2%), with a visit lasting an average of 50 min. According to the scores on the PICS, a high proportion of patients felt fully/very close with their HCP before V1 (71.4%) and before V2 (85.7%) (), with perceived closeness remaining stable for 71.4% of patients after the two visits. Similarly, 52.4% of HCPs reported a stable closeness across the visits, while 28.6% of HCPs reported feeling closer after V2.

Satisfaction with communication during SoC consultation

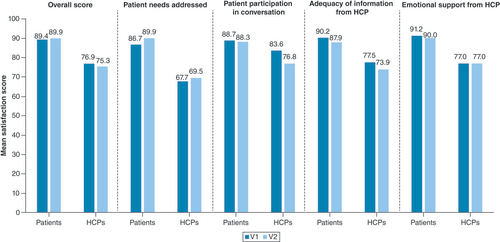

Patients and HCPs reported different levels of overall satisfaction on the Patient/Physician Satisfaction Questionnaire. Patients reported mean overall satisfaction scores of 89.4 and 89.9 at V1 and V2, respectively; for the same consultations, the corresponding HCPs reported mean overall satisfaction scores of 76.9 and 75.3. When adjusted for the perceived closeness of the patient–HCP relationship, patients reported mean overall satisfaction scores of 85.0 and 85.9 at V1 and V2, respectively; for the same consultations, the corresponding HCPs reported mean overall satisfaction scores of 73.8 and 72.4.

Similarly, satisfaction scores with regard to specific aspects of their conversation were different for patients and HCPs, with patients’ mean scores being higher than those of HCPs (). Specifically, HCPs reported low mean satisfaction scores of 67.7 and 69.5 for ‘patient needs addressed’ at V1 and V2, respectively, with corresponding mean scores of 86.7 and 89.9 from the patients. Both patients and HCPs reported relatively high mean satisfaction scores for ‘patient participation in conversation’ at V1 and V2 (patients: V1 = 88.7, V2 = 88.3; HCPs: V1 = 83.6, V2 = 76.8).

Communication of pain

Overall pain experience on day of visit

According to the scores on the single question used to investigate patients’ overall pain experience (see Supplementary Material 2 for further information), a high proportion of both patients (66.7%) and HCPs (61.9%) reported that the pain they/their patient was experiencing was affecting them ‘quite a bit’ or ‘very much’ on the day of V1. Similarly, a high proportion of patients (61.9%) and HCPs (66.7%) reported that the pain they/their patient was experiencing was affecting them ‘somewhat’ or ‘quite a bit’ on the day of V2.

Interference of pain with aspects of daily life during the past week

Patients and HCPs also reported the degree to which pain interfered with certain aspects of their/their patient’s daily life using the interference scale of the BPI. Using validated thresholds to descriptively categorize these pain interference scores according to severity [Citation22], most patients rated their overall pain interference as ‘severe’ (V1: 57.1%; V2: 47.6%) or ‘moderate’ (V1: 33.3%; V2: 42.9%) at both study visits. Similarly, most HCPs rated their patient’s overall pain interference as ‘severe’ (V1: 42.9%, V2: 33.3%) or ‘moderate’ (V1: 42.9%, V2: 61.9%) at both study visits.

Aspects of total pain

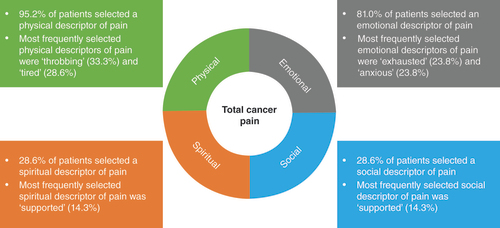

When using the MACPT conversation tool to describe their recent experience of pain, patients most frequently selected descriptors within the physical pain category (95.2%), followed by descriptors in the emotional (81.0%), social (28.6%) and spiritual (28.6%) pain categories. The most frequently selected descriptors for each category can be found in .

Usefulness of the MACPT conversation tool

Patient perspective

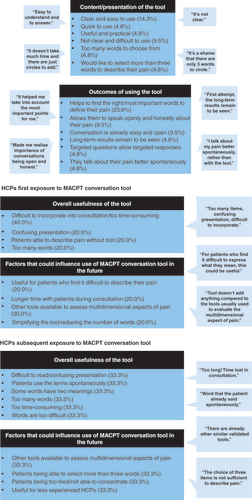

On average, patients rated both the overall usefulness of the tool and the ease of use during consultation as 6.0/10. Furthermore, 81.0% of patients reported finding all the words that best described their pain on the tool, and 66.7% of patients reported that they would like to use the tool with their doctor again in the future. Through open-text responses, patients further commented that the tool helped them to find the right, or most important, words to define their pain (23.8%) and that the content and presentation of the tool was clear and easy to use (14.3%) ().

HCP perspective

A total of five HCPs (two from the UK and three from France) provided feedback following their first use of the MACPT conversation tool. HCPs rated the overall usefulness of the tool as a 2.4/10 and provided similar mean scores for the tool’s ability to help patients communicate and improve conversation (4.2/10), whether they would continue to use the tool (3.4/10) and whether they would recommend the tool to a colleague (2.8/10). However, the HCPs considered the timing of the tool’s administration (i.e., prior to the consultation) appropriate (8.0/10). Through open-text responses, 40.0% of these HCPs reported that it would be difficult to incorporate the tool into consultations and/or that the tool is too time-consuming. Three HCPs responded to the open-text questions following subsequent uses of the MACPT conversation tool and provided similar responses ().

Discussion

This study demonstrated that patients and HCPs were satisfied with the communication during both SoC consultations; that is, both before and after use of the MACPT conversation tool. However, patients were more satisfied than HCPs with their overall conversation and with specific aspects of the conversation. These findings are consistent with previous literature reports stating that patient-reported satisfaction (both overall and regarding specific aspects of the conversation) in an outpatient cancer setting was generally high and greater than HCP-reported satisfaction [Citation23]. The authors concluded that HCPs may be more critical of the communication during consultations and may have differing expectations, both of which may have contributed to the difference in patient- and HCP-reported satisfaction in this study.

A high proportion of patients and HCPs reported that the pain they/their patient was experiencing was affecting them ‘somewhat’, ‘quite a bit’ or ‘very much’ at the time of both study visits. Further, a high proportion of patients and HCPs rated their/their patient’s overall pain interference as ‘severe’ or ‘moderate’ at the time of both study visits. Of note, individuals with cancer pain receiving care in a specialist setting such as a hospital-based outpatient setting, where the majority of study visits took place, generally are more likely to receive adequate treatment for their pain and report lower pain severity than those in non-specialty community-based settings (defined as individuals’ homes, care homes or hospices) [Citation7,Citation24].

When describing their pain using the MACPT conversation tool, patients most frequently selected words in the physical and emotional pain categories. While words in the social and spiritual pain categories were selected to a lesser extent, they were still endorsed by almost one-third of the sample. These findings are in line with previous research demonstrating that patients with multiple myeloma experience physical, emotional and social aspects of pain [Citation25]. As such, the results demonstrate the need for continued education on total cancer pain, for both patients and HCPs, and the importance of HCPs truly considering the holistic nature of pain during SoC consultations (i.e., adopting a biopsychosocial model of pain, or considering ‘total pain’) [Citation11,Citation12]. Although the findings may suggest that the physical and emotional aspects of pain are more important to patients than the social and spiritual aspects, these findings may reflect the characteristics of the sample. Firstly, most patients had experienced bone pain within the last 12 months. Although this was to be expected given the inclusion of patients with advanced breast cancer, prostate cancer, lung cancer and multiple myeloma, where bone metastasis is frequently experienced [Citation1,Citation26], this may have resulted in the more frequent selection of physical pain descriptors – especially as patients could only select three words to describe their pain. Secondly, the most frequently reported concomitant conditions post-onset of cancer were depression and anxiety, meaning patients may have also been more predisposed to describing their cancer pain using emotional descriptors. As such, the social and spiritual aspects of cancer pain may have been more relevant to a more diverse sample of patients. Patients may also need to be encouraged to explore the holistic nature of total cancer pain in order to recognize the importance of the social and spiritual aspects of their pain.

Overall, individuals with advanced cancer generally provided positive responses regarding the usefulness of the MACPT conversation tool during SoC consultations and reported that the tool helped them find the right words to define their pain and was easy to use. However, responses did vary across patients, with some reporting that they already had an easy and open conversation with their HCP. HCPs were less positive regarding the tool’s usefulness, although the most frequently reported issue was that the time-consuming nature of the tool made it difficult to incorporate into routine consultations. These attitudes have been reported in previous literature where HCPs acknowledged the importance of effective communication and shared decision-making in the oncology setting but reported being limited by time constraints during consultations [Citation27]. However, there may be scope to reduce the perceived burden of the tool by providing both patients and HCPs with further support to improve implementation during consultations. Such training should highlight how the MACPT conversation tool, aiming to facilitate a comprehensive dialogue with regard to the physical, emotional, social and/or spiritual aspects of pain (according to the three words selected by the patient), is not a replacement for existing validated measures that focus on the assessment of pain, such as the BPI [Citation21]. The MACPT conversation tool is focused on supporting a more open and comprehensive dialogue on cancer pain and what the pain means to the individual. As such, it can be used in conjunction with these existing validated measures. HCPs should also be made aware of the positive attitudes expressed by patients, such as the conversation tool helping them to find the right words to define their pain, as well as the ways in which the tool can be used (Supplementary Material 4). It is important to acknowledge, however, that this study did not explore the long-term benefits of using the MACPT conversation tool in SoC consultations, nor how use of the tool may impact the management or outcomes of advanced cancer pain. These aspects could be explored in future studies, along with ways to increase value from the HCP perspective.

A limitation of the study was the small size and lack of diversity in both the patient and HCP samples. As such, it is important to acknowledge that the conclusions are based on descriptive results alone and that generalizability to a larger population of advanced cancer patients and HCPs may be limited. The small sample size partly reflects recruitment challenges that were faced, some of which resulted from the study design; for example, it was essential that both study visits were conducted within a 2-month period and with the same HCP. However, these recruitment challenges were later exacerbated by the global COVID-19 pandemic which resulted in changes to patients’ treatment plans and meant that many individuals with advanced cancer were no longer attending face-to-face SoC consultations and that HCP/site nurse availability was further limited. A further limitation was the burden on participants due to the number of questionnaires they were required to complete before and after both study visits. This is particularly pertinent as the patients involved had advanced forms of cancer. However, every effort was made to reduce burden where possible and to only collect data that were directly relevant to the study aims. Further, all participants were made aware that they could choose to leave the study early at any point if they so wished.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that overall satisfaction with SoC face-to-face consultations differed between the patient and HCP perspectives, highlighting the need for improved communication on both sides. Patients most frequently selected physical and emotional pain descriptors on the MACPT conversation tool. However, social and spiritual pain descriptors were also endorsed. These findings highlight the need for continued patient and HCP education on the holistic nature of advanced cancer pain. Opinions with regards to the usefulness of the MACPT conversation tool varied, with patients expressing more positive opinions than HCPs. However, these findings are limited by the small sample size and the lack of demographic diversity.

This study investigated the ‘Managing Advanced Cancer Pain Together’ (MACPT) conversation tool to support comprehensive dialogues on total (physical, emotional, social, spiritual) cancer pain between individuals with advanced cancer and healthcare professionals (HCPs) during standard-of-care consultations.

Patients and HCPs completed two study visits at consecutive face-to-face standard-of-care consultations. The first study visit (V1) was conducted per usual practice, the second (V2) using the MACPT conversation tool.

Due to the small sample size (21 patients and six HCPs, from two clinical sites in the UK and one in France), only descriptive results are presented.

Patients and HCPs were satisfied with the communication during their consultation at both study visits, with patients reporting the greatest satisfaction (patients: V1 = 89.4/100, V2 = 89.8/100; HCPs: V1 = 76.9/100, V2 = 75.3/100).

Most patients and HCPs reported that their/their patient’s pain moderately or severely interfered with daily activities (patients: V1 = 90.4%, V2 = 90.5%; HCPs: V1 = 85.8%, V2 = 95.2%).

Patients most frequently selected physical pain descriptors (95.2%) on the MACPT conversation tool, followed by emotional (81.0%), social (28.6%) and spiritual (28.6%) pain descriptors.

While patients reported that the MACPT conversation tool was useful and helped them describe their pain, HCPs were less positive, reporting that the tool would be difficult to incorporate into consultations.

The study highlights the need for improved communication and education on the holistic nature of total cancer pain for individuals with advanced cancer and their HCPs.

Author contributions

B Quinn was the Chief Investigator for the study. B Quinn, S Dargan, D Lüftner, M Di Palma, L Drudge-Coates and L Dal Lago are members of the MACPT group who developed the MACPT conversation tool and participated in the study design and discussions. C Panter and J Flynn participated in the study design, study conduct, analysis, discussions and write-up of this study. A Seesaghur participated in the study design and discussions. S Laurent, S Dargan and M Lapuente were principal investigators at clinical sites who recruited for this study. All authors contributed to the development of this manuscript and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical conduct of research

Ethical approval and oversight for the study was provided by the Health and Social Care Research Ethics Committee (REC) and the Health Research Authority in the UK (REC reference: 18/NI/0147), the Comite de Protection des Personnes in France (identification code: 20160376) and the ethics committee at Charité hospital (the German clinical site, identification code: EA4/197/19). Informed consent was obtained from all participants (patient and healthcare professionals) included in the study, prior to any study-related activities being conducted.

Supplemental document 1

Download MS Word (45.9 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the doctors at the clinical sites who worked hard to recruit participants for the study, including K Mezaib, M-A Seveque and H Thelu. The authors would also like to thank the journal reviewers for their thoughtful comments and efforts to refine the paper.

Supplementary data

To view the supplementary data that accompany this paper please visit the journal website at: www.tandfonline.com/doi/suppl/10.2217/pmt-2021-0066

Financial & competing interests disclosure

Funding for this research was provided by Amgen Ltd. C Panter and J Flynn are employees of Adelphi Values, a health outcomes research agency, commissioned by Amgen to conduct this study. A Seesaghur is an employee of and holds stock options in Amgen Ltd. D Lüftner has received honoraria from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Celgene, Eli Lilly, GSK, Loreal, MSD, Mundipharma, Mylan, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Tesaro and Teva. M Di Palma has received honoraria from Amgen, AstraZeneca, MSD, Mundipharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi and Tesaro. L Dal Lago has received honoraria from Amgen. B Quinn has received an educational grant from AMGEN and Colpal. L Drudge-Coates has received honoraria from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Astellas Pfizer and Bayer. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Coluzzi F , RolkeR , MercadanteS. Pain management in patients with multiple myeloma: an update. Cancers11(12), 2037 (2019).

- Hamood R , HamoodH , MerhasinI , Keinan-BokerL. Chronic pain and other symptoms among breast cancer survivors: prevalence, predictors, and effects on quality of life. Breast Cancer Res. Treat.167(1), 157–169 (2018).

- Autio KA , BennettAV , JiaXet al. Prevalence of pain and analgesic use in men with metastatic prostate cancer using a patient-reported outcome measure. J. Oncol. Pract.9(5), 223–229 (2013).

- Potter J , HigginsonIJ. Pain experienced by lung cancer patients: a review of prevalence, causes and pathophysiology. Lung Cancer43(3), 247–257 (2004).

- Van Den Beuken-Van MH , HochstenbachLM , JoostenEA , Tjan-HeijnenVC , JanssenDJ. Update on prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Pain Symptom Manage.51(6), 1070–1090.e1079 (2016).

- Mantyh PW . Cancer pain and its impact on diagnosis, survival and quality of life. Nat. Rev. Neurosci.7(10), 797–809 (2006).

- Raphael J , HesterJ , AhmedzaiSet al. Cancer pain: part 2: physical, interventional and complimentary therapies; management in the community; acute, treatment-related and complex cancer pain: a perspective from the British Pain Society endorsed by the UK Association of Palliative Medicine and the Royal College of General Practitioners. Pain Med.11(6), 872–896 (2010).

- Gunnarsdottir S , DonovanHS , WardS. Interventions to overcome clinician-and patient-related barriers to pain management. Nurs. Clin. North Am.38(3), 419–434; v (2003).

- Breivik H , ChernyN , CollettBet al. Cancer-related pain: a pan-European survey of prevalence, treatment, and patient attitudes. Ann. Oncol.20(8), 1420–1433 (2009).

- Jespersen E , NielsenLK , LarsenRF , MöllerS , JarlbœkL. Everyday living with pain-reported by patients with multiple myeloma. Scand. J. Pain21(1), 127–134 (2021).

- Mehta A , ChanLS. Understanding of the concept of ‘total pain’: a prerequisite for pain control. J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurs.10(1), 26–32 (2008).

- Saunders C . The Management of Terminal Malignant Disease (1st Edition).Edward Arnold, London (1978).

- Brant J . Holistic total pain management in palliative care: cultural and global considerations. Palliat. Med. Hosp. Care Open J.1, S32–S38 (2017).

- International Association for the Study of Pain . Total cancer pain. www.iasp-pain.org/Advocacy/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=1106

- Clark WC , Ferrer-BrechnerT , JanalMN , CarrollJD , YangJC. The dimensions of pain: a multidimensional scaling comparison of cancer patients and healthy volunteers. Pain37(1), 23–32 (1989).

- Kremer E , AtkinsonJH , IgnelziR. Measurement of pain: patient preference does not confound pain measurement. Pain10(2), 241–248 (1981).

- Quinn B , LuftnerD , DiPalma M , DarganS , DalLago L , Drudges-CoatesL. Managing pain in advanced cancer settings: an expert guidance and conversation tool. Cancer Nurs. Pract.16(10), 27 (2017).

- Dal Lago L , DiPalma M , Drudge-CoatesL , LuftnerD , DarganS , QuinnB. Managing advanced cancer pain together (MACPT). SIOG 2017 – Abstract Submission (2017).

- Popovic M , MilneD , BarrettP. The scale of perceived interpersonal closeness (PICS). Clin. Psychol. Psychother.10(5), 286–301 (2003).

- Grogan S , ConnerM , NormanP , WillitsD , PorterI. Validation of a questionnaire measuring patient satisfaction with general practitioner services. Qual. Health Care9(4), 210–215 (2000).

- Tan G , JensenMP , ThornbyJI , ShantiBF. Validation of the Brief Pain Inventory for chronic nonmalignant pain. J. Pain5(2), 133–137 (2004).

- Shi Q , MendozaTR , DueckACet al. Determination of mild, moderate, and severe pain interference in patients with cancer. Pain158(6), 1108–1112 (2017).

- Zandbelt LC , SmetsEM , OortFJ , GodfriedMH , DeHaes HC. Satisfaction with the outpatient encounter. J. Gen. Intern. Med.19(11), 1088–1095 (2004).

- Deandrea S , MontanariM , MojaL , ApoloneG. Prevalence of undertreatment in cancer pain. A review of published literature. Ann. Oncol.19(12), 1985–1991 (2008).

- Quinn B , LudwigH , BaileyAet al. Physical, emotional and social pain communication by patients diagnosed and living with multiple myeloma. Pain Manag. doi:10.2217/pmt-2021-0013 (2021) ( Epub ahead of print).

- Von Moos R , CostaL , RipamontiCI , NiepelD , SantiniD. Improving quality of life in patients with advanced cancer: targeting metastatic bone pain. Eur. J. Cancer71, 80–94 (2017).

- Waljee JF , RogersMA , AldermanAK. Decision aids and breast cancer: do they influence choice for surgery and knowledge of treatment options?J. Clin. Oncol.25(9), 1067–1073 (2007).