Abstract

Background: The objective was to determine whether an erector spinae plane (ESP) block could provide additional postoperative analgesic benefits compared with a transversus abdominis plane block. Methods: 78 patients were separated into two groups (n = 39 per group). Both groups received bilateral injections of 266 mg Exparel® (20 ml) and 60 ml of 0.125% bupivacaine. Patients undergoing a transversus abdominis plane block received these injections intraoperatively, while patients undergoing an ESP block received these preoperatively. Outcomes were measured based on scores in opioid usage; pain (visual analog scale) at rest and with movement; nausea; sedation and patient satisfaction. Results: There were no significant intergroup differences in any category (all scores had p > 0.05). Conclusion: No additional analgesic benefits were found using the ESP block procedure.

Plain language summary

The focus for this study was to determine whether there is an alternative method to reduce pain after a laparoscopic hysterectomy. The standard practice at our hospital is to use a method called transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block: injection of a local anesthetic into a region between the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles. The alternative method we studied is known as an erector spinae plane (ESP) block: injection of the same anesthetic into a different region, between the erector spinae muscle and the transverse process of the vertebrae. Our study separated 78 women who met specific criteria into two groups: one using transversus abdominis plane block and the second using ESP block to decrease pain after the procedure. We primarily used a visual analog scale to measure pain levels after treatment. We also used additional parameters like opioid usage and side effects to measure the effects each treatment had on postoperative pain. We found that both methods were similarly effective in lowering pain. The ESP block did show a trend toward less opioid use, which is beneficial for patients following this procedure, but the data collected did not show a significant difference between the two approaches in alleviating pain.

Clinical Trial Registration: NCT04003987 (ClinicalTrials.gov)

Each year, thousands of hysterectomies are performed for various indications including cancer, fibroids, endometriosis and other conditions. Laparoscopic hysterectomy is often complicated by postoperative pain, making pain control challenging, especially with the use of opioids. Improved pain control increases patient satisfaction and may lead to an improved postoperative course [Citation1,Citation2]. Our standard of practice at Indiana University Hospital (IUH) is to perform transverse abdominis plane (TAP) block using liposomal bupivacaine for these patients to help with postoperative analgesia [Citation3]. Evidence suggests that bupivacaine injections to trocar sites are an effective and safe approach for reducing postoperative pain following a laparoscopic hysterectomy, with lower postoperative rescue doses used [Citation4]. Recent literature suggests that erector spinae plane (ESP) block may be a safe and effective alternative for thoracic, extremity and abdominal surgeries [Citation5]. Currently, there are numerous case reports supporting the use of ESP block [Citation6] but there are no prospective randomized controlled trials comparing these two blocks to date. Our study aims to compare the efficacy of ESP block and TAP block in laparoscopic hysterectomy.

The ESP block, first described by Forero, provides regional anesthesia targeting in the range of the T2–L1 branches of thoracolumbar nerves [Citation7]. The ultrasound is positioned in a parasagittal fashion, lateral to the spinous process, to visualize the transverse process. The needle is inserted cranial-to-caudal into the plane traversing through the trapezius muscle, the rhomboid major muscle and the erector spinae muscles, aiming to make contact with the transverse process, with the needle tip deep to the plane of the erector spinae muscle, which overlies the transverse process. Injection of saline confirms the correct location of the needle as determined by cranio-caudal spread of saline under the erector spinae muscle, ‘lifting’ it off the transverse process. Once the correct location is identified, the local anesthetic is injected.

The TAP block consists of injecting local anesthetics between the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles to achieve a blockage of the somatic nerves to the skin, muscles and parietal peritoneum of the anterior abdominal wall [Citation8]. This procedure has been shown to provide effective analgesia following a variety of abdominal surgeries.

The primary objective of this study is to determine the difference between ESP and TAP blocks in controlling postoperative pain by analyzing visual analog scale (VAS) scores taken at both rest and with movement. We plan to use Exparel®, or a liposomal formulation of bupivacaine, as the analgesia for both arms of the study. Because Exparel® is in liposomal form, the lipid solubility allows bupivacaine to be released over an extended period of time. It is reported to provide long-lasting analgesia for up to 72 h and may result in decreased opioid consumption and shortened hospital stays [Citation9–11]. There is no current standard of practice for local anesthesia in ESP block. Liposomal bupivacaine has good analgesia coverage for up to 72 h postoperatively when compared with normal saline and has also been suggested to reduce postoperative opioid use [Citation12,Citation13]. All patients in this study received oral acetaminophen and oral gabapentin on the morning of the surgery and were then placed on prescribed oxycodone/acetaminophen (Percocet) postoperatively. Although not utilized in this study, there has been some evidence for sugarless chewing gum as an additional, affordable alternative with beneficial effects on bowel motility and postoperative pain following a laparoscopic hysterectomy [Citation14]. The secondary objective for this study includes comparing the difference between ESP and TAP blocks in achieving decreased opioid requirements, decreased opioid side effects (nausea, sedation, respiratory depression etc.), assessment of postoperative patient satisfaction; and measuring first flatus, incidence of urinary retention, incidence of respiratory depression, ambulation activity and hospital length of stay.

Patients & methods

Study design

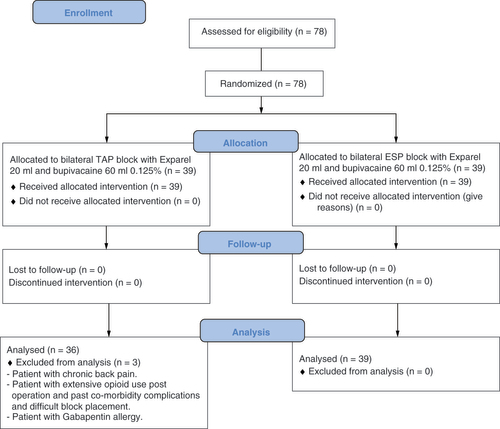

This study was a prospective, double-blinded, randomized controlled trial. Rather than a simple two-group randomization, the study used block randomization which kept the study groups fairly balanced throughout enrollment. The primary investigator informed the person performing the block as to which group the patient was randomized to; however, both the patients and the research staff doing assessments were blinded to the randomization. This study underwent local institutional review board approval and was registered in the National Library of Medicine (23 June 2019, NCT04003987).

Patient enrollment/randomization

All laparoscopic hysterectomy cases scheduled by obstetricians and gynecologists at IUH were identified and the patients were contacted prior to surgery. Patients were informed about the study and all of their questions were answered. A total of 78 subjects were selected and were randomized by a computer program into two groups (39 in each group). One group consisted of patients undergoing a TAP block and the other group were the patients undergoing an ESP block.

Specific inclusion criteria were upheld for patients who participated in the study. The patients must have been females, at least 18 years of age and undergoing laparoscopic hysterectomy at IUH. The patient also must have been in the American Society of Anesthesiologists classification 1, 2, 3 or 4 and they must have desired regional anesthesia for postoperative pain control.

Exclusion criteria were used to disqualify patients who had comorbidities, concomitant treatments, or factors which could have affected the results of the study. These criteria included: any contraindication for ESP or TAP blocks; history of substance abuse in the past 6 months; patients on more than 30 mg morphine equivalents of opioids; any physical, mental or medical conditions which may confound quantifying postoperative pain resulting from surgery; known allergies or other contraindications to the study medications (acetaminophen, gabapentin, bupivacaine); postoperative intubation; or BMI greater than 40.0.

TAP block procedures

The TAP blocks were all performed intraoperatively after induction of the patient. All procedures were done using sterile technique with masks, hats and sterile gloves. These procedures were placed under the supervision of the attending anesthesiologist on the Acute Pain Service. Each of these anesthesiologists had performed over 100 TAP blocks in the preceding 2 years. The ultrasound probe was placed transverse to the abdominal wall, between the iliac crest and the costal margin. The needle was then placed in the plane of the probe and advanced until it reached the space between the internal oblique and the transversus abdominis muscles. Once in the plane, 2 ml of saline was injected to confirm needle position, then the local anesthetic solution was injected [Citation15]. The anesthesiologist from the Acute Pain Service injected 266 mg Exparel (20 ml) and 60 ml of 0.125% bupivacaine. A total of 40 ml was injected on each side, 20 ml for the subcostal TAP and 20 ml for the posterior TAP.

ESP block procedures

The ESP blocks were performed preoperatively prior to induction of the patient. As with the TAP blocks, the ESP block procedures were done using sterile techniques and were placed under the supervision of the attending anesthesiologist on the Acute Pain Service. The ultrasound probe was positioned in a parasagittal fashion, 5–7 cm lateral to the spinous process, to visualize the transverse process. The needle was then inserted cranial-to-caudal to make contact with the shadow of the transverse process, placing the needle tip deep to the fascia of the erector spinae muscle. Correct location of the needle was confirmed by injecting saline and visualizing it spread in a linear pattern within the interfascial plane between the erector spinae muscle and the transverse process [Citation16]. The anesthesiologist from the Acute Pain Service then injected the local anesthetic solution in the ESP space. Using ultrasound guidance, 266 mg Exparel (20 ml) and 60 ml of 0.125% bupivacaine was injected into the patients in the ESP block group. A total of 40 ml was injected on each side, 20 ml at T8 and 20 ml at T12.

Postoperative analgesia & monitoring

At the end of the laparoscopic hysterectomy, patients were tested in the post-anesthesia care unit for the efficacy of their block by cold sensation test. In addition to the peripheral nerve blockades, patients experiencing severe breakthrough pain in either group received prescribed intravenous dilaudid.

Opioid usage was recorded by a member of the research team who was blinded from the group assignments at 1, 24 and 48 h after the ESP or TAP blocks were performed. Pain scores at rest and on movement were measured by the investigator using the VAS from 0 to 10 (no pain = 0; worst pain imaginable = 10). Nausea was measured using a categorical system (none = 0; mild = 1; moderate = 2; severe = 3). Sedation scores were also assessed by a blinded member of the research team using a sedation scale (awake and alert = 0; quietly awake = 1; asleep but easily roused = 2; deep sleep = 3). All of these parameters were assessed at 1, 24 and 48 h after the procedures. Patients were encouraged to begin ambulation on postoperative day 1 under supervision, and their ambulation activity was recorded.

Patients were monitored by the primary team during the postoperative period. There were no reports of any adverse events or unanticipated problems involving (but not limited to) local anesthetic toxicities, or any abdominal injuries during the study. The patients were permitted to withdraw from the study at any time. Criteria for discharge included tolerance of fluid and absence of nausea or vomiting. Patients are typically discharged on day of surgery or on postoperative day 1.

Statistical consideration

The statistical analysis was performed using a standard statistical program (R). We excluded observations with total morphine equivalent dose >100 mg or missing morphine equivalent dose. All demographic data were summarized (means, standard deviations, standard errors and ranges for continuous variables; frequencies and percentages for categorical variables) by group. These four groups were then compared using Mann–Whitney U test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. For the primary outcome, VAS scores at 24 and 48 h were compared between the groups using a covariate adjusted linear mixed effects model; this model included fixed effects for group, time, age, BMI, length of surgery, morphine equivalent dose and the group by time interaction and random individual effects to characterize autocorrelation between repeated measurements.

Pain and satisfaction scores and opioid usage over time were analyzed using a covariate adjusted linear mixed effects model or generalized linear mixed effects model. As with the primary analysis, all models included individual random effect. The analytical model of pain and satisfaction scores included group, time, age, BMI, length of surgery, morphine equivalent dose and the group by time interaction as fixed effects. The analytical model of opioid use included group, time, age, BMI, length of surgery and the group by time interaction as fixed effects.

Group sample sizes were determined from a statistical power analysis. Based on prior studies, the coefficient of variation for the VAS score at 24 and 48 h was estimated at 0.70. The study would have a 90% power to detect a ratio of means of 1.6 for the VAS score between the two groups with a sample size of 39 per group, assuming a two-sided test conducted at the 5% significance level.

Results

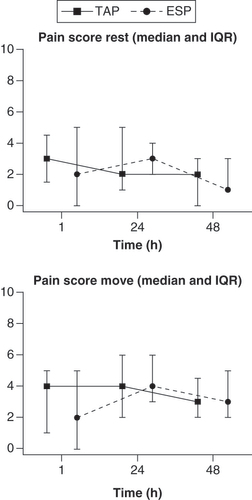

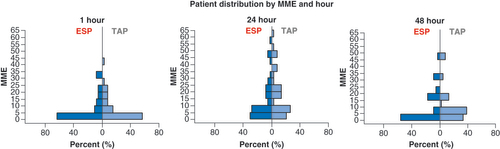

A total of 77 patients undergoing laparoscopic hysterectomy who met all criteria were included in the study (). The patient demographics and surgery duration were similar between both groups (). Pain scores at rest and with movement across all time points recorded (1, 24 and 48 h) showed no significant differences (p > 0.05) between groups ( & &). Opioid usage (all converted to oral morphine equivalent) () as well as sedation () and nausea () scores (across all time points as well as maximum scores) were found to be similar between groups. Satisfaction scores () at 24 and 48 h did not show any significant difference between each of the groups. No unanticipated complications or adverse events were noted for any patient.

ESP: Erector spinae plane; TAP: Transversus abdominis plane.

Table 1. Patient demographics.

Table 2. Mean and median pain scores at rest at 1, 24 and 48 h.

Table 3. Mean and median pain scores with movement at 1, 24 and 48 h.

There were no statistically significant differences between the groups either at rest or with movement.

ESP: Erector spinae plane; IQR: Interquartile range; TAP: Transversus abdominis plane.

Table 4. Opioid usage converted to oral morphine milligram equivalent dose at 1, 24 and 48 h.

Table 5. Sedation scores assessed at 1, 24 and 48 h.

Table 6. Nausea scores assessed at 1, 24 and 48 h.

Table 7. Patient satisfaction scores assessed at 1, 24 and 48 h.

Discussion

Our study comparing ESP block versus TAP block for laparoscopic hysterectomy did not show a statistically significant significance in pain scores, opioid usage or patient satisfactions between the two groups. Although our data were ruled statistically insignificant, there was a trend toward decreased opioid usage in the ESP group (). This trend was most likely not statistically significant due to the number of patients who were included in the study. We also noticed higher mean pain scores and opioid usage at some of the time points in the group that received TAP blocks. Although these findings were not statistically significant, they follow the trend of the ESP block decreasing opioid usage and providing better pain control.

ESP: Erector spinae plane; MME: Morphine milligram equivalent; TAP: Transversus abdominis plane.

Clinically, the surgeon also observed better pain control with ESP patients. Our lack of support for ESP blocks producing additional analgesic benefits does not definitively rule out the important role this alternative may play in other procedures. There could be several reasons why we could not find significant differences. First, the average pain scores in both groups were low to start with (mean VAS score 3–4). With VAS pain scores that are so low in both groups, it is unlikely that we are going to see statistically significant differences between the groups. These findings suggest that both procedures provide pain relief for patients who undergo laparoscopic hysterectomy. A previous study showed that TAP blocks following a total abdominal hysterectomy significantly reduced pain scores compared with patients in a placebo group [Citation17]. Second, the study included a low number of patients. Due to the nature of the procedures being laparoscopic surgery, the procedure itself may not produce enough postoperative discomfort to display a noticeable difference in the alleviation of pain between groups, unless the number of patients studied was higher. Previous data have shown that laparoscopic hysterectomies are considered superior to total abdominal hysterectomies because of reduced postoperative pain and a quicker return to daily routine [Citation18].

Our study showed that the ESP block provides similar analgesic benefits to TAP block for laparoscopic hysterectomies. However, studies have shown that this may not be the case for other types of surgeries. A recent study showed that the ESP block significantly reduced the time patients spent in the intensive care unit following a mitral and/or tricuspid valve repair [Citation19]. The TAP block has also been shown to produce less analgesia compared with the ESP block following a cesarean section procedure [Citation20,Citation21]. Although ESP and TAP blocks have comparable data, they both significantly reduce intraoperative rescue fentanyl, post-anesthesia care unit morphine analgesia, 24-h morphine and pain assessment scores compared with a control group [Citation22].

Conclusion

After comparing ESP and TAP blocks, no significant analgesic benefit was found in using ESP block for this type of operation. There were no significant changes in opioid usage, pain scores or satisfaction scores between groups. However, we saw a noticeable trend toward decreased opioid use in patients who received ESP block. The researchers also noted that, clinically, the ESP patients seemed to have better pain control than the TAP patients. Further research with a higher number of patients is required to determine whether ESP block could provide additional pain relief for laparoscopic hysterectomy or other common laparoscopic procedures.

Laparoscopic hysterectomies are commonly complicated by postoperative pain.

Current standard of practice at the Indiana University Hospital is to perform a transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block to aid with postoperative analgesia.

Prior studies have shown evidence that bupivacaine injections are an effective and safe method for decreasing postoperative pain after a laparoscopic hysterectomy.

Erector spinae plane (ESP) blocks may provide additional analgesic benefits to reduce opioid usage, pain at rest and movement, nausea and sedation and to improve overall patient satisfaction.

This study focused on the possibility of using ESP blocks as an alternative for the current standard of practice TAP block.

ESP block provided similar analgesic benefits to TAP blocks for laparoscopic hysterectomies.

There was a trend of ESP block decreasing opioid usage and pain but this trend was not statistically significant.

Further research should include a higher number of patients in the study to possibly display noticeable differences in alleviation of pain following a laparoscopic hysterectomy.

There may be a role for ESP block to reduce postoperative pain for different abdominal surgeries.

Author contributions

M Warner and K Kasper came up with the research idea and got institutional review board approval for the study. They were instrumental in maintaining the quality of the study. Y Yeap and G Rigueiro collected the data, wrote the manuscript and analyzed the data with the statistician, P Zhang. P Zhang prepared all the tables and figures. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Ethical conduct of research

The authors state that they have obtained appropriate institutional review board approval or have followed the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for all human experimental investigations. In addition, for investigations involving human subjects, informed consent has been obtained from the participants involved.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Data sharing statement

The authors certify that this manuscript reports original clinical trial data. Individual, de-identified data will not be made publicly available. All data collected including pain scores, opioid usage, nausea and sedation scores have been made available at clinicaltrials.gov. The institutional review board protocol and statistical analysis documents are also available at clinicaltrials.gov.

References

- Shaffer EE , PhamA , WoldmanRLet al. Estimating the effect of intravenous acetaminophen for postoperative pain management on length of stay and inpatient hospital costs. Adv. Ther.33(12), 2211–2228 (2017).

- Routman HD , IsraelLR , MoorMA , BoltuchAD. Local injection of liposomal bupivacaine combined with intravenous dexamethasone reduces postoperative pain and hospital stay after shoulder arthroplasty. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg.26(4), 641–647 (2017).

- Bacal V , RanaU , McIsaacDI , ChenI. Transversus abdominis plane block for post hysterectomy pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol.26(1), 40–52 (2019).

- Hortu I , TurkayU , TerziHet al. Impact of bupivacaine injection to trocar sites on postoperative pain following laparoscopic hysterectomy: results from a prospective, multicentre, double-blind randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol.252, 317–322 (2020).

- Tsui BCH , FonsecaA , MunsheyF , McFadyenG , CarusoTJ. The erector spinae plane (ESP) block: a pooled review of 242 cases. J. Clin. Anesth.53, 29–34 (2019).

- Petsas D , PogiatziV , GalatidisTet al. Erector spinae plane block for postoperative analgesia in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a case report. J. Pain Res.11, 1983–1990 (2018).

- Forero M , AdhikarySD , LopezH , TsuiC , ChinKJ. The erector spinae plane block: a novel analgesic technique in thoracic neuropathic pain. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med.41(5), 621–627 (2016).

- Yeap YL , WolfeJW , KroepflE , FridellJ , PowelsonJA. Transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block for laparoscopic live donor nephrectomy: continuous catheter infusion provides no additional analgesic benefit over single-injection ropivacaine. Clin. Transplant.34(6), e13861 (2020).

- Vyas KS , RajendranS , MorrisonSDet al. Systematic review of liposomal bupivacaine (Exparel) for postoperative analgesia. Plast. Reconstr. Surg.138(4), 748e–756e (2016).

- Hutchins JL , KeshaR , BlancoF , DunnT , HochhalterR. Ultrasound-guided subcostal transversus abdominis plane blocks with liposomal bupivacaine vs. non-liposomal bupivacaine for postoperative pain control after laparoscopic hand-assisted donor nephrectomy: a prospective randomised observer-blinded study. Anaesthesia71(8), 930–937 (2016).

- Dominguez DA , ElyS , BachC , LeeT , VelottaJB. Impact of intercostal nerve blocks using liposomal versus standard bupivacaine on length of stay in minimally invasive thoracic surgery patients. J. Thorac. Dis.10(12), 6873–6879 (2018).

- Hadzic A , MinkowitzHS , MelsonTIet al. Liposome bupivacaine femoral nerve block for postsurgical analgesia after total knee arthroplasty. Anesthesiology124(6), 1372–1383 (2016).

- Wu ZQ , MinJK , WangD , YuanYJ , LiH. Liposome bupivacaine for pain control after total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res.11(1), 84 (2016).

- Turkay Ü , YavuzA , Hortuİ , TerziH , KaleA. The impact of chewing gum on postoperative bowel activity and postoperative pain after total laparoscopic hysterectomy. J. Obstet. Gynaecol.40(5), 705–709 (2020).

- Tsai H-C , YoshidaT , ChuangT-Yet al. Transversus abdominis plane block: an updated review of anatomy and techniques. Biomed. Res. Int.2017, 8284363 (2017).

- Hamed MA , GodaAS , BasionyMM , FargalyOS , AbdelhadyMA. Erector spinae plane block for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing total abdominal hysterectomy: a randomized controlled study original study. J. Pain Res.12, 1393–1398 (2019).

- Calle GA , LópezCC , SánchezEet al. Transversus abdominis plane block after ambulatory total laparoscopic hysterectomy: randomized controlled trial. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand.93(4), 345–350 (2014).

- Beyan E , İnanAH , EmirdarV , BudakA , TutarSO , KanmazAG. Comparison of the effects of total laparoscopic hysterectomy and total abdominal hysterectomy on sexual function and quality of life. BioMed Res. Int.2020, e8247207 (2020).

- Borys M , GawędaB , HoreczyBet al. Erector spinae-plane block as an analgesic alternative in patients undergoing mitral and/or tricuspid valve repair through a right mini-thoracotomy – an observational cohort study. Wideochir. Inne Tech. Maloinwazyjne15(1), 208–214 (2020).

- Malawat A , VermaK , JethavaD , JethavaDD. Erector spinae plane block and transversus abdominis plane block for postoperative analgesia in cesarean section: a prospective randomized comparative study. J. Anaesthesiol. Clin. Pharmacol.36(2), 201–206 (2020).

- Boules ML , GodaAS , AbdelhadyMA , AbuEl-Nour Abd El-Azeem SA , HamedMA. Comparison of analgesic effect between erector spinae plane block and transversus abdominis plane block after elective cesarean section: a prospective randomized single-blind controlled study. J. Pain Res.13, 1073–1080 (2020).

- Ibrahim M . Erector spinae plane block in laparoscopic cholecystectomy, is there a difference? A randomized controlled trial. Anesth. Essays Res.14(1), 119–126 (2020).