Abstract

Background: No population-based epidemiological studies have estimated pain prevalence and its characteristics in Peru. Patients & methods: A representative sample of adults aged over 18 years (n = 502) living in metropolitan Lima, Peru was enrolled. We analyzed prevalence data of pain in the last 3 months and other pain-related characteristics. Results: Pain prevalence was 65.3% (95% CI: 57.7–70.4%). Chronic pain prevalence was 38.5% (95% CI: 33.5–44.0%) and acute pain prevalence was 24.8% (95% CI: 20.7–29.0%). In participants with chronic pain, almost half (55.7%) reported having not used any medication. Conclusion: Pain is prevalent in this population and our results suggest high undertreatment rates.

Plain language summary

Although pain is a very important health problem, little is known in Peru about how many people it affects and what its characteristics are. This study aimed to determine the frequency of pain and other related characteristics such as type and location. A sample of inhabitants of metropolitan Lima were surveyed in their homes and were asked about their pain experience in the last 3 months. We found that about seven out of ten had experienced pain in the last 3 months. More than one-third of the participants had pain that lasted more than 3 months (chronic pain). Nearly one-half of the participants with chronic pain had not used any medication to manage their pain. In conclusion, pain is prevalent in the Peruvian population and the results suggest that a large proportion of these people did not receive adequate medical treatment.

Pain is a priority public health problem due its high frequency [Citation1,Citation2]. Although it is a symptom from several conditions, it is also considered a specific condition requiring management regardless of its cause. According to the latest report of estimates of the Global Burden of Disease study, three musculoskeletal disorders characterized by chronic pain (low back pain, neck pain and osteoarthritis) were leading causes of global disability [Citation3]. Pain and, specifically, chronic pain conditions affect biopsychosocial outcomes [Citation4–7] and life expectancy [Citation8] and have economic consequences in people and countries [Citation9,Citation10]. Other diseases or health conditions with a significant disease burden, such as cancer, surgeries and injuries, also have pain as the primary symptom associated with disability [Citation1,Citation3]. Evidence indicates that improper management of acute pain would directly impact chronicity and associated mortality [Citation11,Citation12]. Despite the considerable advances in the understanding of pain that have occurred in recent decades [Citation13,Citation14], a systematic approach and the inclusion of pain in the public health policy agenda are still a pending task worldwide, especially in the developing countries, where there is a lack of data on its magnitude and distribution [Citation2].

Evidence indicates that the prevalence of chronic pain varies considerably, with estimates between 11 and 58.2% depending on the studies [Citation14,Citation15]. Although pain is unquestionably prevalent worldwide, the available evidence about its epidemiology is limited, with the majority of studies from developed countries [Citation15–26] and very little knowledge of the prevalence of pain in developing countries, where the prevalence of pain has been shown to have high heterogeneity and a high burden of associated disease [Citation27]. In Latin America, the majority of studies come from Brazil [Citation27–30] and focus primarily on specific chronic pain conditions [Citation31–37], with very little information available from other Latin American countries [Citation38–40]. As long as there are no exact figures for the magnitude and distribution of chronic pain and pain in these regions with limited economic resources, an adequate approach to pain as a public health problem will be unfeasible [Citation27].

In Peru, evidence related to the local epidemiology of chronic and acute pain is very limited. There is still no comprehensive evaluation of pain, its chronicity, characteristics and impact on the quality of life among Peruvians. The few studies available have focused on specific chronic pain conditions [Citation41] or acute pain [Citation42], both evaluated separately. Although chronic pain deserves a more extensive and detailed examination, acute pain is also important, at least when we make a first approximation to the epidemiology of pain. Furthermore, given that acute pain can become chronic, knowing the magnitude and distribution of the former also helps us better understand the latter. To our knowledge, no previous population-based study in Peru provides a detailed characterization of the epidemiology of pain – both acute and chronic – based on representative samples. Therefore the present study aimed to address this knowledge gap by estimating the prevalence of self-reported pain and its associated characteristics in a representative sample of adults from Lima, Peru (a city that contains almost a fifth of the country’s entire population).

Patients & methods

Design, setting & sampling design

This cross-sectional study was designed to measure the experience and related characteristics of pain in a representative sample of adults from Lima, Peru [Citation43]. According to the National Institute of Statistics and Informatics, close to one-fifth of the country’s population (about 6 million people) live in Lima [Citation43].

The target population was adults aged 18–70 years and living in metropolitan Lima. We carried out a four-stage probability sampling. Metropolitan Lima was divided into five strata according to geopolitical characteristics: north, east, south, residential and central Lima. Into each stratum, census maps were built using a grid system for quadrat sampling. In the first stage, a simple random selection of census maps was made. In the second stage, blocks were randomly selected in each census map chosen previously. For the third stage, a systematic sampling of two dwellings was carried out in each selected block. A simple random sample of one person per dwelling was carried out using a Kish selection grid for the fourth stage [Citation44]. If the selected person was not found, an attempt was made to contact them again or to reschedule a future interview. When this was impossible, the person was replaced by someone with similar sex and age characteristics (±5 years) from the working block. The sampling frame was cartographic and was based on the census, block and housing maps of the 2017 census [Citation45]. We calculated a sample size of 504, assuming a prevalence of pain of 50%, a confidence level of 95% and an error margin of 4.4% for a finite population of 6,764,073 [Citation45].

Variables & questionnaires

The primary outcome variables were related to pain. The variable ‘pain in the last 3 months’ was assessed through the participant’s self-reported answer to the following question: “During the last 3 months, even up to today, have you felt or had pain in any part of your body?”. Participants were given a figure with a list of 15 body sites: head, knee, lumbar, back, hand and wrist, shoulder, neck, ankle and foot, leg, abdomen, hip, elbow, chest, face and thigh. Participants were presented with two full-body images and asked to point to the location of the pain in the last 3 months. Based on these responses, the variable number of sites with pain in the previous 3 months was constructed by assigning the selected location on the image with one of the body sites.

We used the Spanish version of the McGill Pain Questionnaire [Citation46] to measure the pain characteristics. These were only evaluated for those sites that the participant reported caused them the most concern. In this case, the participant could choose between one or two body sites of pain that had caused them the greatest concern in the last 3 months. Based on the responses obtained for both pain sites that caused the participant the most concern, variables were constructed to evaluate all participants’ current pain (on the day of the interview). These variables related to the type of pain according to onset (acute or chronic), initial pain intensity level and pain frequency. Pain intensity was evaluated for the pain that most concerned the participant using a numerical rating scale (NRS) that asked patients to rate pain intensity from 1 (lowest pain level) to 10 (worst pain). We categorized the NRS into three groups: mild pain (NRS 1–3), moderate pain (NRS 4–6) and severe pain (NRS 7–10). Similarly, the time of onset of the first pain was evaluated using a question with four alternatives: ‘less than 1 week’, ‘between 2 and 4 weeks’, ‘between 1 and 3 months’ and ‘more than 3 months’. This was used to categorize the pain as ‘acute’ if the time was 3 months or less, and ‘chronic’ if the time was more than 3 months.

Quality of life was assessed using the quality of life scale of the American Chronic Pain Association (ACPA). The ACPA’s quality of life scale is a single-item questionnaire designed to measure the impact of pain on the daily functioning of people with pain. Previous studies have also used the ACPA’s quality of life scale [Citation47,Citation48]. Its score is rated from 0 (‘non-functioning’) to 10 (‘normal quality of life’). We categorized these quality of life scores as low (score 0–5), medium (score 6–7) or high (score 8–10).

The questionnaire collected information on age, marital status, the highest level of education attained, current occupation, type of health insurance, zone of origin and socioeconomic level regarding sociodemographic variables. Comorbidities (diabetes mellitus and high blood pressure) were assessed through self-reporting. To avoid having variable levels with a low frequency of observations, some variable categories were regrouped. Thus marital status was categorized as ‘single’, ‘married/cohabiting’ or ‘separated/divorced/widowed’. The highest educational level was categorized as ‘no study/primary’, ‘secondary’, ‘higher technical’ or ‘higher university’. The socioeconomic level was evaluated through the socioeconomic categorization of the district into ‘A/B’ (richest districts), ‘C’, ‘D’ and ‘E’ (poorest districts) according to the classification proposed by the Peruvian National Institute of Statistics and Informatics [Citation49].

Statistical analysis

The data were imported into R version 4.0.3 for Windows 10 Pro 64-bit for cleaning and preparation for analysis. An initial data analysis was performed to evaluate the distribution of numerical variables and the presence of outliers and missing data. Due to the small percentage of missing values, it was decided to perform a complete case analysis. Numerical variables were described as mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile range) as appropriate, and their ranges were reported. Categorical variables were expressed as weighted absolute frequencies and relative frequencies in percentages. Graphical methods were used to summarize some results of interest. It is important to note that the weighting factors are not designed to expand the sample absolute frequencies as estimators of the population absolute frequencies; therefore only the percentages can be considered valid for the population aged 18–70 years of metropolitan Lima evaluated from February to March 2020, while the absolute frequencies are only referential.

The comparison between distributions of categorical variables was performed using the χ-square test with Rao and Scott’s second-order correction. Comparison of the means of numerical variables was performed using the Wald test for complex samples and comparison of medians using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for complex samples. Finally, the prevalence of pain in the last 3 months and other pain-related variables was estimated. It is important to note that for the variables ‘current pain’ and ‘pain in each body zone’ (e.g., headache, low back pain), the prevalence was estimated using the total study population as the denominator and not only those who reported pain in the last 3 months. In this way, the prevalence estimates can be generalized to the population aged 18–70 years in metropolitan Lima as evaluated between February and March 2020. In the case of the pain characteristics that most concerned the participants, the prevalences reported only apply to the subpopulation who reported having pain in the last 3 months. In all cases, prevalences were reported with their respective 95% CIs calculated from the logit method and robust standard errors estimated using the Taylor linearization method [Citation50].

All analyses were performed considering the complex sampling structure through the survey package [Citation51] in R v. 4.0.3.

Results

Participant characteristics

Of a total of 502 participants surveyed, 50.4% were women. The mean age was 39.5 years (standard deviation: 14.4; range: 18–70). About half of the participants were cohabiting or married (49.8%), reached the secondary level of education (41.6%), reported working full-time (54.3%) and belonged to a district of socioeconomic level C (56.1%). The main health insurance type was Comprehensive Health Insurance (‘Seguro Integral de Salud’; 34.4%), followed by the Health Social Security (EsSalud; 29.4%); however, about one-quarter (24.8%) of those who participated did not have any insurance. Regarding comorbidities, self-reported high blood pressure and diabetes mellitus were present in 3.9 and 3.2% of respondents, respectively. The distribution of the sociodemographic characteristics of the total study population and the presence of pain is detailed in .

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of study participants.

Pain prevalence

Pain prevalence (acute or chronic) in the last 3 months for the adult population of metropolitan Lima was 65.3% (95% CI: 57.7–70.4). Chronic pain prevalence was 38.5% (95% CI: 33.5–44.0) and acute pain prevalence was 24.8% (95% CI: 20.7–29.0); however, in 2.0% of participants, we could not determine the chronicity of the pain. The number of self-reported body sites with pain in the last 3 months ranged from one to eight.

Among those who had pain in the last 3 months, 43.7% (95% CI: 38.9–48.6) reported having pain in a single body site, 16.3% (95% CI: 12.6–20.8) reported having pain in two different body sites and 5.2% (95% CI: 3.5–7.7) reported pain in three or more body sites. Study participants who reported having pain in the last 3 months were asked for each body site where they had pain and indicated the one that caused them the greatest concern. Almost all (99.8%) of the participants who had pain in the past 3 months reported that one or more of these pains caused them concern. Specifically, in the total population (including those who had and did not have pain in the last 3 months), 43.7% (95% CI: 38.9–48.6) reported having had a single pain that caused or was causing concern and 21.5% (95% CI: 17.0–26.9) indicated having had a pain that caused concern in at least two sites of their body.

In relation to the prevalence of current pain, it is noteworthy that almost one-third of the study population (32.2%; 95% CI: 27.5–37.4) indicated having had pain on the day of the interview. More than one-quarter (28.6%; 95% CI: 24.1–33.6) of the total population also indicated that this current pain was the same one that had most concerned them within the last 3 months.

Reporting having had pain in the last 3 months was associated with a higher median age than having no pain (41 vs 32 years; p < 0.001). The current occupation was significantly associated with pain in the last 3 months (p < 0.001); specifically, those who worked part-time (85.8%) or did not study or work (80.6%) reported a higher prevalence of pain in the last 3 months, by about 20%, compared with those who worked full-time (61.1%) or in household activities (68.6%). Finally, the residential sector was also significantly associated with pain in the last 3 months (p = 0.009). The north and residential Lima sectors had the highest prevalence of pain in the previous 3 months (77.4 and 72.7%, respectively). The southern sector had the lowest prevalence of pain in the last 3 months (49.8%).

Body sites with pain in the last 3 months in the total population & according to sex

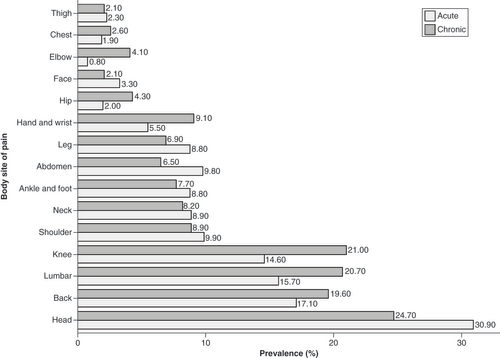

The body sites with the highest frequency of self-reported pain (chronic and acute) in the last 3 months were the head, lower back, upper back and knee. Independently of the chronicity status, we estimated that the prevalence of headaches in the last 3 months was 17.6% (95% CI: 13.3–22.9) in the adult population of metropolitan Lima. The estimated prevalence of lower back pain in the last 3 months was 12.4% (95% CI: 9.3–16.4), while the estimated prevalence of back pain was 11.9% (95% CI: 9–15.8) and knee pain was 11.7% (95% CI: 9.2–14.8). Regarding the differences between men and women in the prevalence of pain (chronic and acute) in the last 3 months specific to body areas, no statistically significant differences were found (p > 0.05). However, it is essential to highlight that, compared with men, women in the study sample had a higher prevalence of pain in the following body sites: hand and wrists (double for women: 6.6 vs 3.3%), head (21.1 vs 14.0%) and leg (also double for women: 6.6 vs 3.3%). Although they were not statistically significant at a significance level of 5%, they were statistically significant at a significance level of 10%. They should be considered preliminary estimates suggesting that the prevalence of pain in these areas could differ according to sex.

Chronicity & other pain characteristics

Regarding the characteristics of the pain that were of the greatest concern in the last 3 months, 68.8% (95% CI: 54.6–66.6) of these were chronic, while 42.1% (95% CI: 35.6–48.8) started with a moderate level of pain, followed by 38.6% (95% CI: 31.8–45.8) with severe pain. The body sites most frequently affected by pain that was of most concern in the last 3 months were the head (22.4%; 95% CI: 16.8–29.2), followed by the upper back (13.4%; 95% CI: 9.6–18.4), lower back (13.3%; 95% CI: 9.5–18.3) and knee (11.6%; 95% CI: 8.5–15.6). We estimated a prevalence of chronic head pain of 24.7%, followed by chronic lower back pain of 20.7%, chronic knee pain of 21.0% and chronic upper back pain of 19.6%. Acute pain had a similar pattern of frequency distributions of affected body sites: acute headache was the most frequent (30.9%), followed by acute upper back pain (17.1%), acute lower back pain (15.7%) and acute knee pain (14.6%) ().

Of the respondents, 42.6% reported that the pain of greatest concern in the last 3 months was sporadic pain, while about one-third reported frequent pain. Among the participants who reported having pain in the last 3 months, 67.0% reported this pain as the only one that caused them concern and 43.9% had this pain on the day of the interview. This pain had a median intensity, as measured with the NRS, of 6. Importantly, 87.5% of the population self-reported with a moderate pain level and 43.2% with a severe pain level at the time of the interview.

We found a statistically significant difference in the prevalence of chronic pain: it was 12.3% higher in men than in women (p = 0.046). Although the median of the initial pain intensity of most concern was one point higher in women than in men (p = 0.046), the direction of this difference was reversed for the current pain intensity, with a median of one point more in men than in women (p = 0.040). details these results.

Table 2. Characteristics of the pain of greatest concern in the population who reported having pain in the last 3 months.

Characteristics of the population with acute & chronic pain

details the comparison of sociodemographic characteristics between those with acute versus chronic pain. The proportion of women was significantly higher (61.8%) in the participants with acute pain than those with chronic pain (p = 0.046). Participants with chronic pain were older than those with acute pain (median age 6 years higher; p = 0.009). The frequency of chronic pain was predominantly sporadic (39.6%) or frequent (38.3%), while acute pain was predominantly sporadic (47.2%) or intermittent (27.4%).

Table 3. Type of the pain of greatest concern in the population who reported having pain in the last 3 months.

Pain & quality of life

Regarding the ACPA’s quality of life scale, the latter was measured only among those who reported having had pain in the last 3 months, so it was not possible to assess their relationship with the presence of pain. However, we could assess the relationship of characteristics of the pain history with the level of quality of life (). The median quality of life score in the participants who reported some pain in the last 3 months was 9, and the average score was 7.5 (range: 1–10). In addition, 50% of these participants had scores between 6 and 9. We observed that a severe initial level of pain was associated with a higher probability of self-reported low quality of life in comparison with a mild or moderate initial level of pain (p = 0.005). Likewise, self-reporting a constant frequency of pain was associated with a higher probability of low level of quality of life in comparisons with other frequency patterns such as sporadic, frequent or intermittent (p = 0.037).

Table 4. Relationship between quality of life level and pain characteristics in participants who had pain in the last 3 months.

Pain management

Of the total population who self-reported any type of pain (chronic or acute) in the last 3 months, only 61.0% (95% CI: 54.3–67.4) received drug treatment; 27.4% (95% CI: 21.4–34.3) did not receive any type of treatment and one-tenth (10.0%; 95% CI: 7–13.9) received physiotherapy or rehabilitation. On the other hand, the prevalence of use of NSAIDs was 41.2% (95% CI: 35.1–47.6), while only 3% (95% CI: 1.5–6.0) reported having used a weak opioid. In participants with chronic pain, almost one-half (55.7%) reported having not used any medication; 39.8% reported having used only NSAIDs and 4.5% a weak opioid alone or in combination with NSAIDs.

Regarding pain management according to its intensity, the use of medications/drugs was up to 15% higher in those with severe pain compared with those with mild pain, but these differences were only marginally significant (p = 0.087). On the other hand, the prevalence of usage of NSAIDs was similar irrespective of the self-reported pain intensity (). No participant with mild pain reported using a weak opioid. Those who had moderate or severe pain reported a very low prevalence of weak opioid use (alone or in combination with NSAIDs), at 3.7 and 3.8%, respectively.

Table 5. Comparison of management of pain of greatest concern according to level of pain intensity.

Discussion

We found a pain prevalence in the last 3 months of 65.3%, as well as a chronic pain prevalence of 38.5%. To the best of our knowledge, there are no previous studies that specifically evaluate pain or chronic pain in Peru, so we do not have local figures with which to make direct comparisons. The only two population-based studies conducted in Peru focused on fibromyalgia [Citation41] and musculoskeletal disease pain [Citation42]; thus ours would be the first population-based study to provide evidence about the epidemiology of pain in Peru. Regardless of the figures from other studies, our findings indicate a high prevalence of pain and chronic pain among people living in Lima. The COPCORD study [Citation42] has also reported high prevalence (50.1%) of pain in a representative sample of households in a marginal urban community of Lima, but it only focused on musculoskeletal pain, so its figures probably considerably underestimate the prevalence of pain. This would explain why the prevalence of musculoskeletal pain found by the COPCORD study is 15% lower than that reported by our study.

In Latin America, our results are quite similar to those observed in three population-based studies also conducted in cities in urban areas such as Lima [Citation29,Citation39,Citation40]. In Chile, Bilbeny et al. reported a prevalence of noncancerous chronic pain of 32.1% (95% CI: 26.5–36.0) in a telephone survey conducted in a representative sample of adults (18 years or older) from the Metropolitan Region [Citation39]. Previous studies in Chile have also found a prevalence of pain as high as 41.1% [Citation52]. In Colombia, Días et al. found a prevalence of chronic pain of 33.9% in a directed survey conducted in a representative sample of adult households in the city of Manizales [Citation40]. In Brazil, Souza et al. reported a prevalence of chronic pain of 39% in a telephone survey conducted in a representative sample of adult inhabitants of the Federal District [Citation29]. Other population-based studies in Brazil reported consistently a high prevalence of chronic pain (41.4 and 42%) [Citation53,Citation54].

Although the high prevalence of chronic pain reported in our study was consistent with several previous studies conducted in Latin America, our figures are probably not directly comparable. This same premise would apply to the figures reported in developed countries, where a great heterogeneity of findings is observed with estimates of the prevalence of chronic pain that vary between 11 and 58.2% [Citation15–26,Citation53,Citation54]. As has been widely discussed by several authors, the differences in the definition of the variables (e.g., pain at 3 months, 6 months, 1 year) and the methodologies carried out (e.g., telephone surveys, personal interview) could partially explain such discrepancies. Likewise, cultural, socioeconomic and biological differences could also explain the great heterogeneity of results in the populations.

Our study also revealed that chronic headaches and low back pain, followed by joint pain (in the knee), are the main painful conditions in the Peruvian population. Similar patterns of pain localization have been reported in other Latin American studies [Citation29,Citation40,Citation55]. Regarding the relationship between sex and pain, although studies have shown inconsistent results, the theory indicates that, in general, the susceptibility to pain is higher in women than in men [Citation56,Citation57]. While some studies found no differences between the sexes [Citation29,Citation39], others found a higher prevalence of chronic pain among women [Citation58–60]. Although our study failed to find statistically significant differences in the prevalence of pain between men and women, there is a marginally significant trend that would suggest a higher prevalence of pain in women than in men (69.1 vs 61.3%; p = 0.089).

An important finding of this study was the low frequency of medical treatment reported in participants with moderate or severe pain intensity: 57.4 and 56.1% of participants with moderate and severe pain, respectively, reported not using any medication to manage their pain. Likewise, the drug management of pain was mainly carried out using NSAIDs, with an almost negligible proportion of use of weak opioids and no cases of strong opioid use reported. Although our study cannot make an accurate assessment of which participants met criteria for medical treatment, the low prevalence of analgesic use suggests a high prevalence of undertreatment in the Peruvian population. This is consistent with what has been reported for several Latin American countries [Citation61–63] and reveals the urgent need to address pain as a public health problem, not only because of the consequences for physical and mental health caused by poor management of pain, but also because the relief of pain is a human right.

This study has some strengths to highlight. First, it used probabilistic sampling, which guarantees statistical representativeness of prevalence estimates to the population of Lima, the largest city in Peru that contains almost one-fifth of the country’s population. A common way to obtain samples for estimating prevalence is to restrict the population to patients attending tertiary care centers. However, the hospital population represents only the tip of the iceberg of the group of people who are really in pain; for example, patients who attend tertiary care hospitals tend to have greater severity, complications and comorbidities, so the epidemiology of pain in this group would be very different from that of the general population. If we consider that a large proportion of people with pain do not go to health centers for treatment, a population study with probability sampling, such as ours, can obtain reliable estimates of pain in larger populations. The second strength was that this study used a standardized questionnaire to comprehensively evaluate pain and its characteristics.

This study also has some limitations to mention. First, the validity of the quality of life scale has not been previously verified in the Peruvian population. Second, the prevalence of chronic pain could only be estimated for the pain that most concerned the participant at the time of the interview. Other locations of chronic pain were possibly ignored because they were less of a concern for the participant, so our figures would be underestimated and would provide lower limits for the true prevalence of chronic pain. Third, the participants could have responded erroneously due to bad memory or falsified their answers about the treatment received due to social desirability. However, restricting the period to the last 3 months reduces recall bias, and there would be no reason to think that the prevalence of NSAID use was being affected by social desirability bias. However, it is more likely that the use of opioids could be influenced by social desirability bias, in which case our results would be underestimated. Fourth, the results of this study were limited to metropolitan Lima, a large urban city that concentrates about one-third of the entire Peruvian population. Although we consider it reasonable that the results can be extrapolated to other urban cities in Peru outside of metropolitan Lima, the results are probably not generalizable to people who live in rural areas of the country, so studies focused on these populations are necessary. Lastly, we evaluated the prevalence of chronic pain in a general way by asking about the presence of pain in some body sites lasting more than 3 months. Although this way of evaluating makes it possible to obtain figures about chronic pain, a better estimate of the prevalence could be obtained through instruments that allow a more precise diagnosis. For example, the prevalence of painful clinical entities, such as low back pain, tension-type headache, migraine or neuropathic pain, can be better approximated using instruments specifically validated for these disorders. Future studies could use these instruments to obtain more precise estimates, as well as to evaluate the disease burden of these disorders and their impact on the quality of life of patients.

Conclusion

The prevalence of pain and chronic pain in the last 3 months is high in adults from Lima, Peru. Nearly one-half of the study population reported pain in at least one body site. The most frequent body sites affected by pain (chronic and acute) in the last 3 months were the head, lower back, upper back and knee. Our results suggest that undertreatment is generalized in our population, so future studies should carefully evaluate this aspect. These figures provide the first broad empirical evidence about the epidemiology of pain in the Peruvian population.

Pain is considered a public health problem and is a priority due to its high frequency and burden of disease.

The inclusion of pain in the public health policy agenda is a pending task in developing countries where there is a lack of data on its epidemiology.

There is little knowledge of the prevalence of pain in developing countries, especially in Peru, a Latin American country.

Pain prevalence in Lima, Peru, was 65.3%. Chronic pain prevalence was 38.5% and acute pain prevalence was 24.8%.

Almost one-half of the participants with chronic pain reported having used analgesic medication.

Prevalence of pain in Lima, Peru was high and there was evidence of high undertreatment rates.

Author contributions

E Orrillo Leyva, I Falvy Bockos, C Vela Barba, D Arbaiza Aldazabal, C Estrada Vitorino, J García-Mostajo, H Valderrama Atauje and L Rojas-Cama participated in the design of the study. E Orrillo Leyva, I Falvy Bockos, C Vela Barba, D Arbaiza Aldazabal, C Estrada Vitorino, H Valderrama Atauje and L Rojas-Cama participated in the data acquisition. P Soto-Becerra performed the statistical analysis and interpretation of data, and wrote the first draft version of the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the content of the manuscript and gave final approval for publication. All authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Ethical conduct of research

This study has obtained appropriate institutional review board approval from Comité Institutional de Bioética Via Libre (Lima, Peru) with study code 7789. This study has followed the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data sharing statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available in the computer files of C Estrada Vitorino, J García-Mostajo and P Soto-Becerra, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under the current study license and are therefore not publicly available. However, the data are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with the permission of Grünenthal Peruana.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This study was supported by Grünenthal Peruana. E Orrillo Leyva, I Falvy Bockos, C Vela Barba and D Arbaiza Aldazabal received remunerations for lecture activities from Grünenthal Peruana. C Estrada Vitorino, J García-Mostajo and H Valderrama Atauje are workers of Grünenthal Peruana and received honoraria from it. L Rojas-Cama and P Soto-Becerra received consultancy fees from Grünenthal Peruana. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Goldberg DS , McGeeSJ. Pain as a global public health priority. BMC Public Health11(1), 770 (2011).

- Blyth FM , SchneiderCH. Global burden of pain and global pain policy – creating a purposeful body of evidence. Pain159, S43 (2018).

- Kyu HH , AbateD , AbateKHet al. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 359 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet392(10159), 1859–1922 (2018).

- Mayer S , SpickschenJ , SteinKV , CrevennaR , DornerTE , SimonJ. The societal costs of chronic pain and its determinants: the case of Austria. PLOS ONE14(3), e0213889 (2019).

- Hooten WM . Chronic pain and mental health disorders: shared neural mechanisms, epidemiology, and treatment. Mayo Clin. Proc.91(7), 955–970 (2016).

- Tang NKY , CraneC. Suicidality in chronic pain: a review of the prevalence, risk factors and psychological links. Psychol. Med.36(5), 575–586 (2006).

- Fayaz A , AyisS , PanesarSS , LangfordRM , DonaldsonLJ. Assessing the relationship between chronic pain and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand. J. Pain13, 76–90 (2016).

- Smith D , WilkieR , UthmanO , JordanJL , McBethJ. Chronic pain and mortality: a systematic review. PlOS ONE9(6), e99048 (2014).

- Phillips CJ . The cost and burden of chronic pain. Rev. Pain3(1), 2–5 (2009).

- Phillips CJ . Economic burden of chronic pain. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res.6(5), 591–601 (2006).

- Quinten C , CoensC , MauerMet al. Baseline quality of life as a prognostic indicator of survival: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from EORTC clinical trials. Lancet Oncol.10(9), 865–871 (2009).

- Pogatzki-Zahn EM , SegelckeD , SchugSA. Postoperative pain – from mechanisms to treatment. Pain Rep.2(2), e588 (2017).

- Raja SN , CarrDB , CohenMet al. The revised International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain: concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain161(9), 1976–1982 (2020).

- Cohen SP , VaseL , HootenWM. Chronic pain: an update on burden, best practices, and new advances. Lancet397(10289), 2082–2097 (2021).

- Tsang A , LeeS. The global burden of chronic pain. In: Global Perspectives on Mental-Physical Comorbidity in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys.ScottKM, Von KorffMR, GurejeO ( Eds). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England, 22 (2009).

- Hoy D , BainC , WilliamsGet al. A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain. Arthritis Rheum.64(6), 2028–2037 (2012).

- Manchikanti L , SinghV , FalcoFJE , BenyaminRM , HirschJA. Epidemiology of low back pain in adults. Neuromodulation J. Int. Neuromodulation Soc.17(Suppl. 2), 3–10 (2014).

- Fernández-de-las-Peñas C , Hernández-BarreraV , Alonso-BlancoCet al. Prevalence of neck and low back pain in community-dwelling adults in Spain: a population-based national study. Spine36(3), E213–E219 (2011).

- Fejer R , KyvikKO , HartvigsenJ. The prevalence of neck pain in the world population: a systematic critical review of the literature. Eur. Spine J.15(6), 834–848 (2006).

- Institute of Medicine Committee on Advancing Pain Research, Care, and Education . Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research.National Academies Press (USA), WA, USA (2011).

- Yong RJ , MullinsPM , BhattacharyyaN. Prevalence of chronic pain among adults in the United States. Pain163(2), e328–e332 (2022).

- Todd A , McNamaraCL , BalajMet al. The European epidemic: pain prevalence and socioeconomic inequalities in pain across 19 European countries. Eur. J. Pain Lond. Engl.23(8), 1425–1436 (2019).

- Breivik H , CollettB , VentafriddaV , CohenR , GallacherD. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur. J. Pain Lond. Engl.10(4), 287–333 (2006).

- Kishimoto M , OjimaT , NakamuraYet al. Relationship between the level of activities of daily living and chronic medical conditions among the elderly. J. Epidemiol.8(5), 272–277 (1998).

- Fayaz A , CroftP , LangfordRM , DonaldsonLJ , JonesGT. Prevalence of chronic pain in the UK: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population studies. BMJ Open6(6), e010364 (2016).

- Sessle BJ . Unrelieved pain: a crisis. Pain Res. Manag.16(6), 416–420 (2011).

- Sá KN , MoreiraL , BaptistaAFet al. Prevalence of chronic pain in developing countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Rep.4(6), e779 (2019).

- Garcia JBS , Hernandez-CastroJJ , NunezRGet al. Prevalence of low back pain in Latin America: a systematic literature review. Pain Physician17(5), 379–391 (2014).

- de Souza JB , GrossmannE , PerissinottiDMN , de OliveiraJOJr , da FonsecaPRB , dePaula Posso I. Prevalence of chronic pain, treatments, perception, and interference on life activities: Brazilian population-based survey. Pain Res. Manag.2017, 4643830 (2017).

- de Moraes Vieira EB , GarciaJBS , da SilvaAAM , AraújoRLTM , JansenRCS. Prevalence, characteristics, and factors associated with chronic pain with and without neuropathic characteristics in São Luís, Brazil. J. Pain Symptom Manag.44(2), 239–251 (2012).

- Romero DE , SantanaD , BorgesPet al. Prevalence, associated factors, and limitations related to chronic back problems in adults and elderly in Brazil. Cad. Saude Publica34(2), e00012817 (2018).

- Depintor JDP , BracherESB , CabralDMC , Eluf-NetoJ. Prevalence of chronic spinal pain and identification of associated factors in a sample of the population of São Paulo, Brazil: cross-sectional study. Sao Paulo Med. J. Rev. Paul. Med.134(5), 375–384 (2016).

- de Melo Castro Deligne L , RochaMCB , MaltaDC , NaghaviM , deAzeredo Passos VM. The burden of neck pain in Brazil: estimates from the global burden of disease study 2019. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord.22(1), 811 (2021).

- Saes-Silva E , VieiraYP , deOliveira Saes Met al. Epidemiology of chronic back pain among adults and elderly from Southern Brazil: a cross-sectional study. Braz. J. Phys. Ther.25(3), 344–351 (2021).

- Nascimento PRC do , CostaLOP. Low back pain prevalence in Brazil: a systematic review. Cad. Saude Publica31(6), 1141–1156 (2015).

- Leopoldino AAO , DizJBM , MartinsVTet al. Prevalence of low back pain in older Brazilians: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Rev. Bras. Reumatol.56(3), 258–269 (2016).

- de Carvalho RC , MaglioniCB , MachadoGB , de AraújoJE , da SilvaJRT , da SilvaML. Prevalence and characteristics of chronic pain in Brazil: a national internet-based survey study. BrJP1, 331–338 (2018).

- Covarrubias-Gómez A , Guevara-LópezU , Delille-FuentesRet al. First national summit meeting of delegates of the Mexican Association for the Study and Treatment of Pain. Rev. Mex. Anestesiol.37(2), 142–147 (2014).

- Bilbeny N , MirandaJP , EberhardMEet al. Survey of chronic pain in Chile – prevalence and treatment, impact on mood, daily activities and quality of life. Scand. J. Pain18(3), 449–456 (2018).

- Díaz R , MarulandaF. Dolor crónico nociceptivo y neuropático en población adulta de Manizales (Colombia). Acta Medica Colomb.36(1), 10–17 (2011).

- León-Jiménez FE , Loza-MunarrízC. Prevalencia de fibromialgia en el distrito de Chiclayo. Rev. Medica Hered.26(3), 147–159 (2015).

- Vega-Hinojosa O , CardielMH , Ochoa-MirandaP. Prevalencia de manifestaciones musculoesqueléticas y discapacidad asociada en una población peruana urbana habitante a gran altura. Estudio COPCORD. Estadio I. Reumatol. Clínica14(5), 278–284 (2018).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadistica e Informatica . http://m.inei.gob.pe/prensa/noticias/la-poblacion-de-lima-supera-los-nueve-millones-y-medio-de-habitantes-12031/

- Kish L . A procedure for objective respondent selection within the household. J. Am. Stat. Assoc.44(247), 380–387 (1949).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática . PERÚ: Estimaciones y Proyecciones de Población por Departamento, Provincia y Distrito, 2018–2020 (2020). www.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/publicaciones_digitales/Est/Lib1715/libro.pdf

- Lázaro C , BoschF , TorrubiaR , BañosJ-E. The development of a Spanish questionnaire for assessing pain: preliminary data concerning reliability and validity. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess.10(2), 145 (1994).

- Callan N , HanesD , BradleyR. Early evidence of efficacy for orally administered SPM-enriched marine lipid fraction on quality of life and pain in a sample of adults with chronic pain. J. Transl. Med.18, 401 (2020).

- McMurtry M , ViswanathO , CernichMet al. The impact of the quantity and quality of social support on patients with chronic pain. Curr. Pain Headache Rep.24(11), 72 (2020).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática . Mapa de pobreza monetaria provincial y distrital 2018.Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática, Lima, Peru (2020).

- Lumley T . Complex Surveys: a Guide to Analysis Using R.John Wiley, NJ, USA (2010).

- Lumley T . survey: analysis of complex survey samples (2020). https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/survey/index.html

- Miranda JP , QuezadaP , CaballeroPet al. Revisión sistemática: epidemiología de dolor crónico no oncológico en Chile. Dolor59(2013), 10–17 (2013).

- Sá KN , BaptistaAF , MatosMA , LessaÍ. Chronic pain and gender in Salvador population, Brazil. Pain139(3), 498–506 (2008).

- Cabral DMC , BracherESB , DepintorJDP , Eluf-NetoJ. Chronic pain prevalence and associated factors in a segment of the population of São Paulo City. J. Pain15(11), 1081–1091 (2014).

- Sá K , BaptistaAF , MatosMA , LessaI. Prevalence of chronic pain and associated factors in the population of Salvador, Bahia. Rev. Saude Publica43(4), 622–630 (2009).

- Bartley EJ , FillingimRB. Sex differences in pain: a brief review of clinical and experimental findings. Br. J. Anaesth.111(1), 52–58 (2013).

- Fillingim RB , KingCD , Ribeiro-DasilvaMC , Rahim-WilliamsB , RileyJL. Sex, gender, and pain: a review of recent clinical and experimental findings. J. Pain10(5), 447–485 (2009).

- Portenoy RK , UgarteC , FullerI , HaasG. Population-based survey of pain in the united states: differences among White, African American, and Hispanic subjects. J. Pain5(6), 317–328 (2004).

- Cabezas RD , MejíaFM , SáenzX. Estudio epidemiológico del dolor crónico en Caldas, Colombia. Acta Médica Colomb.34(3), 96–102 (2009).

- Kennedy J , RollJM , SchraudnerT , MurphyS , McPhersonS. Prevalence of persistent pain in the US adult population: new data from the 2010 National Health Interview Survey. J. Pain15(10), 979–984 (2014).

- García CA , GarciaJBS , CookMDRBet al. Undertreatment of pain and low use of opioids in Latin America. Pain Manag.8(3), 181–196 (2018).

- Garcia JBS , LopezMPG , BarrosGAMet al. Latin American Pain Federation position paper on appropriate opioid use in pain management. Pain Rep.4(3), e730 (2019).

- Rico MA , KraycheteDC , IskandarAJet al. Use of opioids in Latin America: the need of an evidence-based change. Pain Med.17(4), 704–716 (2016).