Abstract

Introduction: The use of group work assessment in medical education is becoming increasingly important to assess the competency of collaborator. However, debate continues on whether this does justice to individual development and assessment. This paper focuses on assessing the individual component within group work.

Method: An integrative literature review was conducted and complemented with a survey among representatives of all medical schools in the Netherlands to investigate current practices.

Results: The 14 studies included in our review show that an individual component is mainly assessed by peer assessment of individual contributions. Process and product of group work were seldom used separately as criteria. The individual grade is most often based on a group grade and an algorithm to incorporate peer grades. The survey provides an overview of best practices and recommendations for implementing group work assessment.

Discussion: The main pitfall when using peer assessment for group work assessment lies in differentiating between the group work process and the resulting product of the group work. Hence, clear criteria are needed to avoid measuring only effort. Decisions about how to weigh assessment of the product and peer assessment of individual contribution should be carefully made and based on predetermined learning goals.

Introduction

Medical students are trained to become professionals, who must work together in teams. Medical professionals need to collaborate with colleagues and other health care workers. It is therefore important to address the competency role of “collaborator” in medical education (Frank et al. Citation2015), for example by introducing group work or team-based learning (Davies Citation2009; Parmelee & Michaelsen Citation2010). Group work assessment is the most common way of assessing this competency (Epstein & Hundert Citation2002) and is becoming increasingly important in medical education (Frenk et al. Citation2010). Group work has multiple advantages for learning. It leads to deep and active learning (Davies Citation2009), increased knowledge outcomes, teamwork skills and interactivity (McMullen et al. Citation2014) and staff and student satisfaction (Zgheib et al. Citation2010).

In group work assessment, the group as a whole often receives a single grade for a group product, which is the outcome of the group work—for example, a paper, a presentation, a poster (Cheng & Warren Citation1999). The individual grade for each group member is often identical to this group grade. The question arises whether this does justice to individual skills and development. After all, students receive individual credits that should reflect their personal performance.

When we take a closer look at group work assessment from this perspective, some practice issues arise. For instance, it is often not clear what happens in student teams. When group processes are not closely monitored and contributions of individual students not identified (Watson et al. Citation1993), the validity of group scores for individual students may be challenged. Is the assignment really a task that requires teamwork and collaboration or has it been completed by one individual? How should the issue of free riders be addressed? Free riders are defined as students who do not put effort into group work but hope to benefit excessively from the work of others. The question is as follows: can we identify the individual component in group work and include this in the assessment criteria? Worries about accountability arise when dealing with group assignments, mainly because it is often unclear how individual contributions are assessed. From this perspective, the central issue of this paper is: “How can individual contributions be identified and assessed in group work assessment?” To further specify the aim of our study, we formulated the following research questions:

Which assessment instruments or tools are being used to assess the individual component in group work assessment?

What criteria about process and/or product are being used to assess this individual component?

What procedures or algorithms are being used to determine the individual grade?

To investigate these questions, an integrative literature review (Whittemore & Knafl Citation2005) was conducted on assessment of the individual component within group work. This type of review allows combining different sources of evidence. In addition, we sent out a questionnaire to gain an overview of how group work assessment (and procedures) is used in practice and to identify best practices from all medical schools in the Netherlands. Our goal was to determine the best methods of assessing this individual component (the “I”) in group work.

Methods

A literature search was performed in January 2015, for all articles up to that moment. Medline, PsycINFO, and Educational Resources Information Centre (ERIC) were searched for original articles on the use of group work assessment. The following search terms were used:

“group work” OR “team work” OR “group assignment”

AND scor* OR feedback OR “student evaluation” OR gradi* OR grade* OR marking OR marked OR mark OR rating OR rated OR assess* OR “standard setting” OR judg* OR achiev*

AND learning

AND student* OR education OR undergrad*

The search was first narrowed to “medical education”, but because this resulted in a very low number of articles, we removed this limitation. First, we selected articles that dealt with group work assessment in educational settings. Subsequently, the articles were evaluated to determine whether assessment of the individual component of group work was described in a way that met our additional criteria:

Main inclusion criterion:

Assessment of the individual component of group work is described

Additional inclusion criteria:

The type of group work is described in sufficient detail

Grading/judgment procedures/criteria are described in sufficient detail

Publication in English

In March–April 2015, we used an online questionnaire to gather information on group work assessment in the eight medical schools in the Netherlands. The questionnaire (Supplementary Appendix A) was sent to the members of the Special Interest Group on Assessment of the Netherlands Association for Medical Education working in medical schools (n = 21). The members of this group have several years of experience in the field of assessment in medical education, regarding assessment policy and development in their institution as a member of a board of examiners or faculty management and organization. We deliberately refrained from quantitative description of data from the questionnaire because the sample is too small by default (there are only eight medical schools in the Netherlands).

Results

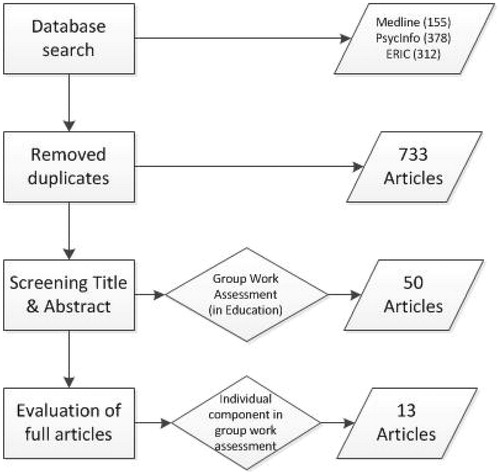

Our initial search resulted in 845 hits [Medline (155), PsycINFO (378), and ERIC (312)—number of articles found in brackets]. After removing duplicate hits, a total of 733 articles were identified and screened based on title and abstract. After we screened the articles and selected the ones that dealt with group work assessment in educational settings, 50 remained. The main inclusion criterion eliminated many articles, because often there was no individual component in the group work assessment. In many instances, the individual assessment was based on a separate assignment or test (e.g. a multiple choice test) independent of the group work assessment. Our additional inclusion criteria were used to test whether the descriptions of the assessment methods were clear enough to enable us to evaluate the results and conclusions of the studies ().

Thirteen articles met our inclusion criteria. During an additional citation search, we identified one (Spatar et al. Citation2015) that cited several of the articles selected and fitted all our inclusion-criteria. We included this paper and ended with a total of 14 articles.

Representatives of all eight Dutch medical schools responded, providing information on the use of group work assessment in their undergraduate curricula, best practices, and experience with addressing an individual component. In total, 14 experts (67%) responded.

The results from the literature review and the questionnaire are presented regarding tools, criteria, and procedures, respectively. Characteristics of the 14 selected studies are described and summarized in .

Table 1. Characteristics of the 14 studies included in the review.

Tools

In most studies, the individual component was assessed using peer and/or self-assessment: 12 studies used peer assessment, seven of which in combination with self-assessment. In one study, the individual component was assessed based on student portfolios (Kuisma Citation2007) and in another on wiki statistics/logs (Caple & Bogle Citation2013). The assessment methods are listed in .

Table 2. Criteria for assessing an individual component in group work, identified in studies in the review.

The respondents in our questionnaire reported assessment of group process using some form of peer assessment. Evaluation by peers was not only utilized to assess aspects that cannot be observed directly by teachers (notably collaboration in the group) but also for educational reasons, as students learn through the evaluation of the assignments of peers.

A written product (report or essay) is reported as the most frequently used tool to assess group work in Dutch undergraduate medical curricula. This written product is often presented orally by students to peers and teachers. Other assignments such as posters, debates, and demonstration of practical skills are mentioned as well.

Criteria

In our review, we found that in peer assessment, process or product were seldom used as separate criteria to evaluate individual students but more often framed as the “contribution to the group work.” This concept of contribution was poorly defined in eight of the 14 studies. The other six used well-described criteria or rubrics regarding the group process. The study by Lejk and Wyvill describes a set of six criteria plus keyword indicators (Lejk & Wyvill Citation2001, Citation2002) that is also used by Sharp (Citation2006), such as motivation, adaptability, creativity, communication skills, general team skills, and technical skills. Strom et al. describe a set of 25 criteria on collaboration skills (Strom et al. Citation1999). In the remaining 10 studies, students were asked to judge the contributions in a more holistic manner. This holistic judgment was sometimes preceded by some preparation by the students. Students were, for example, instructed to reflect on a set of behavior-related questions, for example, concerning peer attendance, effort, responsibility (Dingel & Wei Citation2014). Another way of assessing individual contributions is described by Tucker who used a validated instrument using specific and well-described aspects of group work combined with a more holistic approach (Tucker Citation2013).

In only one study, specific teamwork skills were described and used for individual assessment (Strom et al. Citation1999). In the wiki study by Caple and Bogle (Citation2013), specific aspects of the process were assessed using the Wikispace platform: a History tab revealed the evolution of the page over the duration of the project (and the student responsible for each edit); and the Wiki Statistics function collated every contribution/edit made by an individual member (Caple & Bogle Citation2013). In the study by Kuisma (Citation2007), a portfolio was used for individual grading, and hence, in this case, only reflection on own learning and no peer assessment was used. The content of the portfolios was graded using the SOLO taxonomy (Biggs & Collis Citation1982). Finally, in one study, explicit criteria for evaluating the end product, a presentation, were mentioned. These, as well as a weighting scheme were negotiated with the class (Knight Citation2004).

Respondents to the questionnaire recommended incorporating “collaboration” in the learning objectives and assessment criteria of group work assignments (). Other ways to identify an individual component mentioned were based on assessing an additional individual task related to the group assignment. For example, being responsible for a part of the presentation of results of the group work, or individually answering questions regarding the presentation.

Box 1. Recommendations for group work assessmentTable Footnote*

Procedures

Different approaches to peer-assessment were compared in five studies. The individual grade was most often based on an algorithm taking peer and/or self-assessment into account. Nine such methods were described in the studies, using a formula to differentiate between individual students (Lejk & Wyvill Citation2001, Citation2002; Sharp Citation2006; Zhang & Ohland Citation2009; Maiden & Perry Citation2011; Jin Citation2012; Caple & Bogle Citation2013; Tucker, Citation2013; Takeda & Homberg Citation2014; Spatar et al. Citation2015). These procedures varied in complexity ranging from a holistic view (Lejk & Wyvill Citation2001, Citation2002) to a complex procedure—which normalized raw peer ratings, calculated individual weighting factors, partially corrected for inter-rater agreement and constrained above-average contributions (Spatar et al. Citation2015). In four studies, (Strom, et al. Citation1999; Knight, Citation2004; Kuisma Citation2007; Dingel & Wei Citation2014) such algorithms were not used or reported because they were not relevant to these studies. In all but one study the tutor gave a grade, and in almost all cases, only the end product was used for this grading (). In one study, no tutor assessment was given since the learning objective was to assess teamwork skills in the student group (Strom et al. Citation1999).

Respondents to the survey reported a summative nature of group work assessment as the main purpose in all but one institution. Most respondents reported that a teacher awarded a summative group mark based on assessment of the group product. Yet, some ways to identify an individual component in group work were also applied; similar to methods described in papers included in our review. Summative assessments of group assignments were reported to provide students with a qualification (grade, pass/fail or the like), and also some kind of narrative feedback (written or oral, provided standard or on request). Such narrative feedback may provide students with useful input for future learning.

Free riding is recognized as a potential problem in group work assessment by all of the seven medical schools that use the group work for summative assignments, but most do not regard it as a critical issue. For only one institution, free riding is the reason to only rarely apply such assessment. Others mention strategies or procedures that are applied to minimize free-riding, regarding limited group size (two students), or timely detection by paying attention to the collaboration process by tutors.

Additional findings from the questionnaire

Keys to success for using group work were queried in the questionnaire. Based on experience in the Dutch medical schools, respondents provided several recommendations for using group work in the appropriate way, and ways to avoid risks/limitations. These refer to the task, group composition, attention to the group process, and learning goals and assessment criteria and are summarized in Box 1. More details are provided in the recommendations in the discussion.

Although group work is seen as a means for learning to collaborate and thus is applied for educational reasons, it should be noted that respondents also explicitly mentioned practical reasons for applying group work. Compared to multiple-choice examinations, other forms of assessment, such as essays or papers, are more labor-intensive in terms of staff time needed for correcting. By using group assignments, fewer staff are needed for supervision and correcting compared to individual assessments.

Discussion

This paper intended to answer the question: “How can the individual contributions be identified and assessed in group work?” which we further detailed in (1) Which assessment instruments or tools are being used to assess the individual component in group work assessment? (2) What criteria, about process and/or product are being used to assess the individual component? and (3) What procedures or algorithms are being used to determine the individual grade?

Tools

The studies included in the review show that identifying the individual component is possible and that it is mainly done through peer assessment of individual contributions. This is in agreement with regular practice in medical schools in the Netherlands according to the findings based on the questionnaire.

Although self-assessment is used in half of the studies in our review, we agree with Lejk and Wyvill (Citation2002) and Spatar et al. (Citation2015) who advise not to use self-assessment for identifying the individual component of group work in summative assessments. Self-assessment reduces the variability (Lejk & Wyvill Citation2002), it is not necessary to identify free riders, and students often appear unable to assess themselves (Spatar et al. (Citation2015) for an elaborate discussion on this issue). Yet, for formative assessment and learning opportunities, self-assessment can still be very valuable.

Although the group work or product is important, individual competencies play an important role—Box recommendation 6.

Criteria

We believe that peer assessment is a suitable instrument to address the “I” in group work; however, there is an important pitfall. The assessment of individual contribution may be derived from the perceived effort individual students put in the group product and/or from the perceived participation in the group process (e.g. attendance, active participation, creativity). A recurrent discussion in practice is the distinction between assessing the process or the product of the group work. With peer assessment, it is difficult to differentiate between process and product. This results in collating both with the vague term “contribution.” If the criteria for peer assessment are not clear and well defined, the assessment of individual contribution becomes only an assessment of perceived effort. Therefore, we stress the importance of first defining the learning goals on process and/or product and formulating clear criteria accordingly (see the Box recommendation 7).

Procedures

In almost all studies, a combination of tutor and peer assessment was used to give an individual grade. The reliability of peer assessment is often questioned (Dancer & Dancer Citation1992; Stefani Citation1992; Pond et al. Citation1995; Orsmond et al. Citation1996; Falchikov & Goldfinch Citation2000) and various authors warn to be cautious in weighing peer assessment of contribution into the final grade. Yet, deriving the individual grade largely from the group (product) grade, diminishes individual differences in grades within the group. The decision about weighing these two should be founded on the learning objectives (the Box recommendation 3). If the final product covers the most important learning objectives, more value should be added to it, but if team skills or collaboration skills are most important more weight should be given to peer assessment. Weighing different factors in the decision is always a compromise. Focusing purely on the end product will not do justice to individual contributions. Assessing collaboration skills in a vacuum without taking the final product into account is artificial. On the other hand, if the shared goal of the team (the final product) becomes unimportant in the grading procedure, it will influence the functioning of the team and consequently the validity of the assessment of collaboration skills.

It is important to take the group size into account for group work assessment—see the Box recommendation 2. The group sizes in the studies included in the review were small (maximum 7 students). According to Strom et al. (Citation1999), four to six students per group is ideal. With increasing group size, a group mark becomes less informative of individual performance, so identifying individual performance becomes increasingly important. Hence, the bigger the teams, the more weight the individual component should receive. Related to this is the duration of team compositions. A continuous group process over a longer period of time differs from a single end-of-course activity. Since evaluation of individual contributions during group work provides students with valuable feedback, multiple formative low-stakes assessment moments over a longer period of time are preferred—see the Box recommendation 5 and 7. This enables students to reflect upon the feedback received and improve their teamwork activities. Formative assessments ideally result in a final summative assessment in which formative feedback and improvement steps taken are considered (Schuwirth & Van der Vleuten Citation2011).

Finally, peer assessment can be done in the open or anonymously. When given in secret, more honest comments can be expected. Anonymity in peer assessment is not explicitly addressed in the studies aimed at identifying the individual component, although Lejk and Wyvill (Citation2001) found that the spread of scores is higher in anonymous peer assessment.

Additional issues

During our screening and analysis of the literature, two additional issues in defining group work assessment emerged: (1) student behavior (or attitude) and (2) group composition. Multiple studies found that students’ perceptions towards group work are generally positive (e.g. Knight Citation2004). However, what struck us was that no study linked the characteristics of the grading system to student behavior. Only Jin (Citation2012) found that perceived fairness was not related to the complexity of the grading system. Students do indicate that grading systems that take free-riding behavior into account are preferred over systems that do not (Maiden & Perry Citation2011). Other studies also indicate that staff and students regard the free-riding issue as an important topic (Maiden & Perry Citation2011; Spatar et al. Citation2015). However, identifying free riders should not be the main goal of a grading system. Providing feedback on collaboration skills and identifying students’ strengths and weaknesses should be more valuable.

The second issue concerns biases due to group composition (Takeda & Homberg Citation2014; Dingel & Wei Citation2014; Spatar et al. Citation2015). We acknowledge that the composition of the group is likely to influence how the group functions. There is little evidence to support an argument for gender bias in peer marking (Tucker Citation2013). However, prior to assessment, group composition may influence collaboration during group work—for example, women may have higher team-work skills (Strom et al. Citation1999) and there is evidence that gender balanced groups result in more equitable contributions than imbalanced groups (Takeda & Homberg Citation2014). Still, the practical relevance of group composition for group work assessment is less obvious as the composition of groups in a course is often difficult to influence.

Limitations

Our literature search found only a limited number of studies that assessed the individual component of group work. By excluding studies that do not explicitly assess this we may have missed useful advice and good practices regarding other aspects of group work and group work assessment. However, we believe that an explicit focus on this individual component is needed and easily overlooked in the big picture of group work assessment. Another limitation is our sample, regarding the questionnaire. Although we included all medical schools in the Netherlands, it remains a small number of medicals schools in a culturally uniform area. Other cultures may show different practices and experiences.

Conclusion

In the literature reviewed, we found no clear distinction in motivations for using group work assessment (either to assess collaboration or efficiency). However, we recognize that the relevance of our main question is largely derived from the doubts raised when using group work assessment mainly as a means for efficiency improvement or budget cuts. On the other hand, if the goal is to assess collaboration, we believe the validity argument should also be based on more than a group product and should include the process, both regarding the group as a whole and its individuals.

The question remains: how should a grading system for group work assessment be set up? In the Box, recommendations are provided, collected from the health faculties in the Netherlands. From the studies and the questionnaire, we conclude that the following steps should be considered when constructing and implementing group work assessment.

What are the main learning goals? A decision should be made about the relative importance of product and process.

Does the weighting scheme and formula fit the purpose? Are the criteria for peer assessment well defined? It is worth considering discussing the nature of the contributions to group work and criteria for peer assessment between tutors and students before starting the peer assessment.

Is the end product (task) suitable for group work? (see Box recommendation 1)

Does the group composition give reason to suspect bias in assessment results? If yes: What safety measures are in place to counteract this?

Team skills are not always evident in groups. Provide guidance and opportunities to develop these skills—Box recommendation 4. Provide feedback periodically, not only at the end.

Assessing the individual component within group work is complex, yet feasible and surely worth the effort for both accountability reasons and learning.

Notes on contributors

Joost Dijkstra, PhD, is an educationalist working for Academic Affairs at the Maastricht University Office on Educational and Assessment Policy.

Mieke Latijnhouwers, PhD, is assessment advisor at the Radboud University Medical Center in Nijmegen.

Adriaan Norbart, MA, educational advisor at the Leiden University Medical Center.

René A. Tio, MD, PhD, is an Associate Professor, Center for Education Development and Research in Health Professions (CEDAR) and Department of Cardiology, University of Groningen and University Medical Center Groningen.

Supplemental_Material.docx

Download MS Word (26.2 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all members of the Special Interest Group on Assessment of the Netherlands Association for Medical Education for contributing to this article through discussions on the subject in our SIG-meetings and providing information on the questionnaire. In addition, we thank John O’Sullivan from Leiden University Medical Center, the reviewers and editor, for their useful comments to drafts of this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

References

- Biggs JB, Collis KF. 1982. Evaluating the quality of learning: the SOLO taxonomy. New York (NY): Academic Press.

- Caple H, Bogle M. 2013. Making group assessment transparent: what wikis can contribute to collaborative projects. Assess Eval High Educ. 38:198–210.

- Cheng W, Warren M. 1999. Peer and teacher assessment of the oral and written tasks of a group project. Assess Eval High Educ. 24:301–314.

- Dancer WT, Dancer J. 1992. Peer rating in higher education. J Educ Bus. 67:306–309.

- Davies WM. 2009. Group work as a form of assessment: common problems and recommended solutions. Higher Educ. 58:563–584.

- Dingel M, Wei W. 2014. Influences on peer evaluation in a group project: an exploration of leadership, demographics and course performance. Assess Eval High Educ. 39:729–742.

- Epstein RM, Hundert EM. 2002. Defining and assessing professional competence. JAMA. 287:226–235.

- Falchikov N, J Goldfinch. 2000. Student peer assessment in higher education: a meta-analysis comparing peer and teacher marks. Rev Educ Res. 70:287–322.

- Frank JR, Snell L, Sherbino J, editors. 2015. CanMEDS 2015 Physician Competency Framework. Ottawa: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada.

- Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, Cohen J, Crisp N, Evans T, Kistnasamy B. 2010. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet. 376:1923–1958.

- Jin XH. 2012. A comparative study of effectiveness of peer assessment of individuals' contributions to group projects in undergraduate construction management core units. Assess Eval High Educ. 37:577–589.

- Knight J. 2004. Comparison of student perception and performance in individual and group assessments in practical classes. J Geogr High Educ. 28:63–81.

- Kuisma R. 2007. Portfolio assessment of an undergraduate group project. Assess Eval High Educ. 32:557–569.

- Lejk M, Wyvill M. 2001. Peer assessment of contributions to a group project: a comparison of holistic and category-based approaches. Assess Eval High Educ. 26:61–72.

- Lejk M, Wyvill M. 2002. The effect of the inclusion of self-assessment with peer assessment of contributions to a group project: a quantitative study of secret and agreed assessments. Assess Eval High Educ. 27:551–561.

- Maiden B, Perry B. 2011. Dealing with free-riders in assessed group work: results from a study at a UK university. Assess Eval High Educ. 36:451–464.

- McMullen I, Cartledge J, Finch E, Levine R, Iversen A. 2014. How we implemented team-based learning for postgraduate doctors. Med Teach. 36:191–195.

- Orsmond P, Merry S, Reiling K. 1996. The importance of marking criteria in the use of peer assessment. Assess Eval High Educ. 21:239–249.

- Parmelee DX, Michaelsen LK. 2010. Twelve tips for doing effective team-based learning (TBL). Med Teach. 32:118–122.

- Pond K, Ui-Haq R, Wade W. 1995. Peer review: a precursor to peer assessment. Innov Educ Train Int. 32:314–323.

- Schuwirth LW, Van der Vleuten CP. 2011. Programmatic assessment: from assessment of learning to assessment for learning. Med Teach. 33:478–485.

- Sharp S. 2006. Deriving individual student marks from a tutor's assessment of group work. Assess Eval High Educ. 31:329–343.

- Spatar C, Penna N, Mills H, Kutija V, Cooke M. 2015. A robust approach for mapping group marks to individual marks using peer assessment. Assess Eval High Educ. 40:371–389.

- Stefani AJ. 1992. Comparison of collaborative, self, peer and tutor assessment in a biochemistry practical. Biochem Educ. 20:148–151.

- Strom PS, Strom RD, Moore EG. 1999. Peer and self-evaluation of teamwork skills. J Adolesc. 22:539–553.

- Takeda S, Homberg F. 2014. The effects of gender on group work process and achievement: an analysis through self- and peer-assessment. Br Educ Res J. 40:373–396.

- Tucker R. 2013. The architecture of peer assessment: do academically successful students make good teammates in design assignments? Assess Eval High Educ. 38:74–84.

- Watson WE, Kumar K, Michaelsen LK. 1993. Cultural diversity's impact on interaction process and performance: comparing homogeneous and diverse task groups. Acad Manag J. 36:590–602.

- Whittemore R, Knafl K. 2005. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 52:546–553.

- Zgheib NK, Simaan JA, Sabra R. 2010. Using team-based learning to teach pharmacology to second year medical students improves student performance. Med Teach. 32:130–135.

- Zhang B, Ohland MW. 2009. How to assign individualized scores on a group project: an empirical evaluation. Appl Meas Educ. 22:290–308.