Abstract

Objective: To examine long-term psychosocial distress in women with a history of early onset preeclampsia (PE) compared to a comparison group. Methods: Women with and without a history of early onset PE participating in the ‘Preeclampsia Risk EValuation in FEMales’ (PREVFEM) study were sent questionnaires, on average 14.1 years (SD = 3.2, range 5–23 years) after the index pregnancy. In total 265 (77%) women with PE and 268 (78%) age-matched women without PE returned questionnaires (mean age 43.5, SD =4.6 years). Group differences were examined on indicators of psychosocial distress, depressive symptoms, anxiety, fatigue, loneliness, marital quality, trait optimism and Type D personality, and unadjusted and adjusted for a priori chosen and study-specific covariates. In secondary analyses, the effect of previously detected hypertension was examined, as well as pregnancy-related events within the PE group. Results: Women with a history of PE reported more subsequent depressive symptoms (B = 0.70, 95% CI 0.09–1.32, p = 0.026) and more fatigue (B = 1.12, 95% CI 0.07–2.18, p = 0.037) compared to the non-PE group, but the differences explained less than 1% of the variance. The differences remained after adjustment for age, BMI and education level, and additional adjustment for partner, being unemployed and physical activity. No significant differences were observed for anxiety, loneliness, marital quality, optimism, or Type D personality. These differences were not explained by four-year previously measured elevated blood pressure in the PE group. Having had a stillborn child or early neonatal death during the index pregnancy was associated with higher depressive symptoms, anxiety, fatigue, and loneliness in the PE group, but these factors explained only a small proportion of the variance in these psychosocial distress factors. Conclusion: A history of early PE is associated with slightly higher levels of depressive symptoms and fatigue on average 14 years later, but this is unlikely to be of clinical relevance.

Introduction

Preeclampsia (PE) is a multisystem pregnancy complication defined as new onset hypertension and proteinuria after 20 weeks of gestation [Citation1]. The Preeclampsia Risk EValuation in FEMales (PREVFEM) historic cohort study showed increased hypertension (OR 3.59, 95% CI 2.48–5.20) on average 10 years after the index pregnancy, in women with a history of early onset (20–32 weeks gestation) PE compared to a comparison group without PE [Citation2]. Other studies have consistently shown associations between a history of PE with cardiovascular outcomes, including hypertension, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, stroke, and renal failure, and PE is now an emerging risk factor for future cardiovascular disease (CVD) [Citation2–8]. It is suggested that PE and CVD share common cardiac risk factors such as hypertension, obesity, dyslipidemia, and hyperglycemia/insulin resistance. Psychological factors representing psychosocial distress have been associated with cardiovascular risk factors, as well as with the progression and prognosis of CVD [Citation9]. Recent guidelines for the prevention of CVD have suggested a number of core questions representing psychosocial distress, such as depression, anxiety, fatigue, social isolation, and personality, to be included in future studies on CVD risk assessment [Citation10]. In this respect, psychosocial distress may serve as a proxy for cardiovascular risk [Citation11]. It is currently unknown whether psychosocial distress is part of a shared risk pathway linking a history of PE to cardiac risk factors and eventual cardiovascular disease development.

PE has been associated with more psychological problems; studies have shown that women who have experienced PE report more depressive symptoms, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) up to seven years after their pregnancy [Citation12–15]. In a systematic review on this topic, Delahaije and colleagues described six studies on anxiety, depression, and PTSD in women following PE. Two studies were prospective [Citation13, Citation16], and four utilized a historic cohort [Citation15, Citation17–19]. Depressive symptoms, PTSD, or anxiety were assessed a few months up to on average seven years after pregnancy. Delahaije and colleagues concluded that the findings were inconclusive, which warrants further investigation [Citation14]. Two studies with a follow-up period of on average seven years show inconsistent findings; compared to a control group, Gaugler–Senden and colleagues reported more PTSD symptoms in those who had experienced early PE but no differences in depression [Citation15], whereas Postma and colleagues reported higher anxiety and depressive symptoms [Citation12].

Delahaije further advised adjustment for potential confounders such as age, obesity, and socioeconomic status [Citation14]. On the other hand, pregnancy-related events such as birthweight or perinatal death can be considered as intermediate factors, which may be on the causal pathway between PE and psychological outcomes [Citation14]. These pregnancy-related events could explain within group variation on long-term psychosocial distress. The present study examines psychosocial distress in women with a history of early onset PE and a comparison group, 5–23 years (mean 14 years) after their index pregnancy.

Given the increased risk of PE with cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular disease, and the acknowledgement of psychosocial factors in CVD, it could be postulated that the presence of persistent psychosocial distress after PE is part of a cardiovascular vulnerability profile. Our primary research question was to examine whether having a history of early onset PE was associated with on average 14-year follow-up psychosocial distress when compared to a comparison group, either unadjusted, and adjusted for covariates. A secondary research question was whether psychosocial distress was explained by previously detected elevated hypertension in the PE group compared to the comparison group. The final research aim was to examine pregnancy-related events as intermediate factors within the PE group with long-term follow-up psychosocial distress. We hypothesized that women in the PE group, compared to the comparison group, report increased levels of psychosocial distress. We further hypothesized that the presence of hypertension was associated with more psychosocial distress in the PE group. Finally, we hypothesized that pregnancy-related events affect long-term follow-up psychosocial distress in women with a history of early PE.

Methods

Participants and procedure

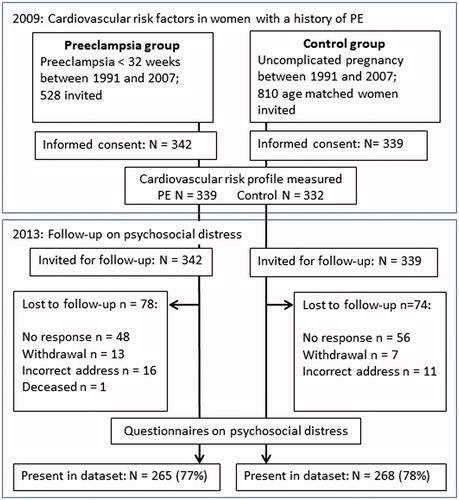

The present study is a four-year follow-up of the PREVFEM study [Citation2]. The PREVFEM historical cohort study was set up in 2009 to examine cardiovascular risk factors in women with a history of early PE. In 2009, all pregnancies that were registered in the Isala hospital records between the years 1991 and 2007 were screened for presence (exposure) or absence (nonexposure) of early onset PE [Citation2,Citation20]. Inclusion criteria for the PE group were early onset PE as defined according to the International Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy (ISSHP) definition; an elevated diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg with proteinuria (≥0.3 g/24 h) between 20 and 32 weeks of gestation during index pregnancy. The non-PE comparison group (non-PE) comprised age-matched women with normotensive pregnancies. Main exclusion criteria were pregnancy or breast-feeding at the time of screening in 2009. Eligible women were invited to participate, and in total, 681 women provided written informed consent, of which 10 did not participate in the data collection of 2009.

In 2013, all participants who had provided written informed consent (N = 681) were invited to participate in the follow-up arm to examine psychosocial distress. Study coded questionnaires with a prestamped return envelope were sent in October 2013. In total, 265 (response rate =77%; 50% of the initial eligible sample) women in the PE group and 268 (response rate =78%; 33% of the initial eligible sample) women in the non-PE group responded ( Flowchart). Approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Isala Klinieken Zwolle (METC nr 08.0853).

Psychosocial distress

Questionnaires on psychosocial distress were based upon the guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice [Citation10]. The questionnaire included sociodemographic data (income, education, and work status), measures of psychological distress (depressive symptoms, anxiety, and fatigue), measures of (absence of) social support (marital quality and loneliness), and two personality scales (optimism and Type D personality).

Depressive symptoms in the previous two weeks were measured with the screening instrument PHQ-9. It comprises 9 items on a 0–3 scale, with a cutoff score of ≥5 indicating mild to severe depressive symptoms [Citation21]. Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was 0.83. Anxiety was measured with the GAD-7, a 7-item scale with a 0–3 scale (Cronbach’s alpha 0.91). Anxiety is represented with a score of 5 or higher [Citation22]. Fatigue was measured with total (summed) score on the ‘Fatigue Assessment Scale’ (FAS), 10-item version on a 1–5 scale, with items 4 and 10 reverse scored [Citation23]. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.87.

Marital quality was assessed as the total score on the 6 item, 0–6 scale MMQ6 scale (Cronbach’s alpha 0.91) [Citation24]. Loneliness was assessed with the 10-item (1–4 scale) UCLA-Revised short (UCLA-R-S) version [Citation25]. Items 2,3,7,9, and 10 are reverse scored, and the total score indicates more loneliness. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.85 in the present study.

Two personality scales were included: the LOT-12 questionnaire was used to assess dispositional trait optimism. It comprises 12 items on a 0–4 scale, and items 3, 8, 9, and 12 are reverse scored. Four filler items [Citation2,Citation6,Citation7,Citation10] are not included in the total score. A higher score indicates more dispositional optimism [Citation26]. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.90. The DS14 measures Type D personality; 14 items (0–4 scale) measure negative affectivity (Cronbach’s alpha =0.88) and social inhibition (Cronbach’s alpha =0.87). A cutoff of 10 on both subscales indicates Type D personality [Citation27].

Descriptives and covariates

Age, living with a partner, education level (primary and/or lower secondary, upper secondary, or higher education; recoded into ‘higher education’ versus ‘other’ for multivariate analyses), employment status (fulltime, part-time, unemployed; recoded into unemployed versus employed for multivariate analyses), and self-reported weight and height for body mass index (BMI). Women filled out items on lifestyle and medication use (Do you … exercise regularly/smoke/use alcohol/use psychotropic medication?), which were dichotomized into physical activity (active versus not active), smoking (‘current or previous smoker’ versus nonsmoker), alcohol use (some versus none), and use of psychotropic medication.

Hypertension was measured as part of the 2009 study on cardiac risk factors, and defined as having systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥ 140 mmHg, a diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 90 mmHg, or use of antihypertensive medication [Citation2].

Information of the index pregnancy comprised time (years) between pregnancy and 2013, whether the pregnancy was the first pregnancy or not, pregnancy duration (weeks), preterm birth (pregnancy duration <37 weeks), birth weight of the child (grams), and whether a child was stillborn (after 24 weeks of pregnancy), or early neonatal death (live born and deceased within seven days after birth).

Statistical analysis

One-way ANOVAs and Chi-square tests were run to examine continuous and categorical differences between the PE and the non-PE group. Effect sizes for One-Way ANOVAs are reported as Partial Eta Squared (η2), for which η2 = 0.01 is a small effect size, 0.06 is a medium effect size, and 0.14 is a large effect size [Citation28]. Effect sizes for Chi-square tests are Cramer’s V, with 0.10 for a small effect size, 0.30 for a medium effect size, and 0.50 for a large effect size [Citation29]. Similar tests were used to examine the association of the descriptives with psychosocial factors.

Multivariate analyses were run to examine the effect of PE on the psychosocial distress factors (outcome variables), unadjusted (Model 1), and adjusted for covariates (Model 2). Multivariate analyses were adjusted for age, higher education, and BMI, which were chosen a priori [Citation14]. There were seven persons with missing BMI data in 2013; for these, the BMI of 2009 was imputed and used in the multivariate analyses. The multivariate analyses were additionally examined when adjusted for parner, higher education, and physical activity (active), based on group differences and consistent associations with psychosocial factors.

Multivariate analyses were used to examine the presence of hypertension in 2009, and the interaction of ‘group by hypertension’ on the psychosocial factors, adjusted for age, higher education, and BMI. The interaction term describes differences between the group with PE and hypertension in 2009, compared to the other groups. There were 11 cases with missing information on the presence of hypertension in 2009.

For the final research aim, associations between index pregnancy-related events and psychosocial factors were examined within the PE group, adjusted for age. These intermediate factors included time since the index pregancy, first pregnancy, preterm birth (<37 weeks), stillborn child, or early neonatal death, and birth weight (recoded into kg).

B scores with 95% CI of B for the continuous variables, and Odds Ratio (OR) with 95% CI for Type D personality, exact p values and the adjusted r2 (r2adj) or Cox and Snell r2 (r2Cox) are reported for the multivariate analyses. All analyses were run with SPSS version 19 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Results

The total group comprised 532 women (mean age 43.5 years, SD =4.6), who were on average 14.1 (SD =3.2) years after their index pregnancy (range: 5.0–23.0 years). The descriptives stratified by PE and non-PE group are shown in . The women with a history of early PE were more often higher educated, with a higher BMI compared to the non-PE group. Women with a history of PE more often had a first pregnancy as the index pregnancy, more often experienced a stillbirth or early neonatal death, had a child with lower birth weight, had on average a shorter amenorrhea duration, and were more likely to have had a preterm birth (). Time that had passed since the index pregnancy was longer for the non-PE group. No differences in physical activity, current smoking, alcohol use, or use of psychotropic medication between the groups were observed.

Table 1. Descriptives stratified by presence or absence of PE.

Psychosocial distress

Psychosocial distress stratified by group is shown in . Women after PE reported significantly more depressive symptoms and fatigue compared to the non-PE group, albeit with very small effect sizes. There were no differences in presence of mild/moderate depressive symptoms according to the cut-off, nor in anxiety, loneliness, marital quality, or personality traits optimism or Type D personality between the groups ().

Table 2. Psychosocial distress at follow-up stratified by the presence or absence of PE.

Sociodemographic and lifestyle covariates were examined in relation to the psychosocial factors, which showed consistently more psychosocial distress for having a higher BMI, not having a partner, being unemployed, not being physically active, and more psychotropic medication use (data not shown).

Multivariate analyses of psychosocial distress are described in . Having had a history of early PE was significantly associated with increased depressive symptoms and fatigue at follow-up. However, PE explained less than 1% of the variance of depressive symptoms and fatigue. PE remained significantly associated with more depressive symptoms and fatigue when adjusted for age, higher education level, and BMI. PE was not significantly associated with follow-up symptoms of anxiety, loneliness, marital quality, and personality traits optimism and Type D personality.

Table 3. Associations of a history of PE with long-term follow-up psychosocial distress.

Additional adjustment for having a partner, being unemployed and physical activity did not alter the main findings ().

Effect of hypertension on psychosocial factors

The effect of having hypertension in 2009 was additionally examined and reported in , adjusted for age, higher education, and BMI. In line with previously reported findings [Citation2], the PE group met criteria for hypertension (n = 114/263; 43%) more often than the non-PE group (n = 37/258; 14%), with a medium effect size (X2 = 54, p < 0.001, Cramer’s V = 0.32). There were no main effects of hypertension or group on psychosocial distress (). When the group*hypertension interaction term was added to the model, the PE group with hypertension showed greater loneliness (B = 2.03, 95% CI 0.02–4.04, p = 0.048), but no other significant interaction terms emerged. The estimate of effect size was small, showing that the adjusted model explained 1.6% of the variance of loneliness. After additional adjustment for partner, being unemployed, and physical activity, PE was significantly associated with depressive symptoms (B = 0.80, 95% CI 0.16–1.45, p = 0.015), and fatigue (B = 1.30, 95% CI 0.19–2.41, p = 0.021), but no significant main effect of hypertension was observed. The significant interaction of PE with hypertension remained associated with loneliness (B = 2.00, 95% CI 0.02–3.99, p = 0.048).

Table 4. The association of early PE with psychosocial factors, adjusted for presence of hypertension in 2009, and group by hypertension interaction.

Effect of index pregnancy-related factors on psychosocial factors within the PE group

Within the PE group, pregnancy-related factors, i.e. time since the index pregnancy, first pregnancy, preterm birth (<37 weeks), stillborn child or early neonatal death, and birth weight were associated with the psychosocial factors, adjusted for age. In the PE group, having had a stillborn or deceased child during the index pregnancy was significantly associated with higher depressive symptoms (B = 2.74, 95% CI 1.22–4.26, p < 0.001), anxiety (B = 2.75, 95% CI 1.17–4.33, p = 0.001), fatigue (B = 3.85, 95% CI 1.20–6.51, p = 0.005), and loneliness (B = 3.04, 95% CI 0.97–5.11, p = 0.004) at follow-up, which explained less than 5% of the variance of the psychosocial factors. Moreover, in the PE group, the index birth weight (in kg) was significantly associated with higher marital quality at follow-up (B = 1.54, 95% CI 0.30–2.79, p = 0.015). A longer time since the index pregnancy was negatively associated with optimism (B = −0.61, 95% CI –0.90 – –0.32, p < 0.001), and ‘first pregnancy’ was associated with more optimism at follow-up (B = 3.38, 95% CI 1.00–5.75, p=.005). No other significant findings were observed (data not shown).

Discussion

Women with a history of early onset PE report similar levels of psychosocial distress on average 14 [Citation5–23] years after pregnancy as measured by anxiety, (absence of) social support, and personality constructs optimism and Type D personality, when compared to a group without PE. A significantly higher level of depressive symptoms and fatigue was observed, albeit with a very small effect size. Adjustment for age, education level, and BMI, and further adjustment for partner, being unemployed, and physical activity did not affect these findings. Our secondary hypothesis was not confirmed; despite an increased prevalence of hypertension (as measured in 2009) in the PE group, hypertension was not associated with long-term psychological distress. One significant interaction term showed that women with PE and hypertension had higher loneliness scores in 2013. Women with PE who had a stillborn child or early neonatal death during index pregnancy reported significantly higher depressive symptoms, anxiety, fatigue, and loneliness at follow-up, which explained a small proportion of the variance of these psychosocial factors.

Delahaije and colleagues in their review examined whether PE patients were more likely to have, or have more severe, anxiety, and depression compared to a reference group [Citation14], with inconclusive findings. Our findings on psychosocial distress on average 14 years after PE are partially in line with two long-term studies on average 7 years after PE; Postma and colleagues [Citation12] showed not only higher depressive symptoms but also more anxiety in 51 PE versus 48 controls. On the other hand, Gaugler–Senden and colleagues [Citation15] did not observe significant differences in depressive symptoms between the PE and the control group at follow-up. Our study comprised a larger sample, with a longer follow-up, showing differences in depressive symptoms with a very small effect size but no differences in anxiety. The significantly higher depressive symptoms and fatigue in the PE group were small, and therefore unlikely to be of clinical relevance.

No main effects of either PE or hypertension on any psychosocial distress factor were observed. However, having elevated hypertension in 2009 in the PE group was associated with more loneliness at follow-up. Hypertension is part of a cardiovascular risk profile. Significant bidirectional associations between hypertension and psychosocial risk factors have been observed, although there is considerable heterogeneity between different studies, and an absence of associations has been observed as well [Citation30–32]. Overall, the present findings do not confirm a strong effect of hypertension as part of a cardiac risk profile, on the association between PE and long-term psychosocial distress.

In the women with a history of early PE, significantly higher levels of depressive symptoms, anxiety, fatigue, and loneliness were reported for those whose child died during the pregnancy or immediately after birth, which explained a small proportion of the variance of these psychosocial distress measures. Other index pregnancy-related factors in the PE group showed that a higher birth weight was associated with higher marital quality; a longer time since index pregnancy was associated with less optimism; and if the index pregnancy was a first pregnancy, this was associated with more optimism at follow-up. Psychological factors are known to be elevated after perinatal loss [Citation33, Citation34], though a nested-case control cohort did not observe more depression on average seven years after stillbirth [Citation35]. In total seven persons experienced perinatal loss in the comparison group, which limits any group comparison in the current study. However, within the PE group, experiencing the loss of a child is more strongly associated with psychosocial distress on average 14 years later than having experienced PE, and hence the loss of a child rather than PE may prove to be a better predictor for long-term distress. Given that the main focus of the present study was not perinatal loss, these findings need to be interpreted with caution.

The review of Delahaije and colleagues argued for the adjustment of relevant confounders, including maternal obesity, low socioeconomic status, and age [Citation14]. We adjusted the present findings for age, higher education level as an indicator of socioeconomic status, and BMI. However these confounders were measured at the same time as the psychosocial distress, and not during the index pregnancy, which is a limitation. Moreover, the adjustment for pregnancy-related factors is argued to be on the causal pathway between PE and psychological distress, and should not be included as confounders. Instead we examined pregnancy-related factors in relation to the psychosocial distress within the PE group.

Strengths of the study include the large sample size, long follow-up term, and the high response rates in both groups. The absence of the measurement of psychosocial distress before the index pregnancy is a limitation, as well as the absence of a measure for PTSD, which is more often investigated in response to PE. Another limitation was that the presence of hypertension was assessed four years previously, which does not guarantee the presence of hypertension in the present study. However, we were able to report the prospective associations of hypertension on four-year follow-up psychosocial distress. Moreover, we do not have information on the initial eligible sample in comparison to the participants in the present study, which may limit generalizability of the findings.

Conclusion

After on average 14 years after having had PE, women show a small elevation in depressive symptoms and fatigue, but not other factors of psychosocial distress. These findings were not confounded by previously measured hypertension. Within the PE group, perinatal loss was associated with more psychological distress. The main differences between the PE group and the non-PE group were small, and therefore unlikely to be of clinical relevance.

Highlights

Current knowledge on the subject

PE has been associated with psychological problems up to seven years after pregnancy

PE is associated with cardiovascular risk factors and poor cardiovascular prognosis

Long-term outcomes of psychosocial distress in women with a history of early preeclampsia are currently unknown

What this study adds

Higher depressive symptoms and fatigue were found on average 14 years after pregnancy in women with PE

The differences were small, and unlikely to be of clinical relevance

These findings were not confounded by previously observed increased hypertension

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Diagram Zwolle/Nijmegen for their contribution to the data collection. Mattanja de Ruiter and Sander Eussen are acknowledged for their contribution in the data collection and data entry, and Lindy Arts and Frederique Hafkamp for their contribution to the data entry as part of their Tilburg University research training and internship.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tranquilli AL, Dekker G, Magee L, et al. The classification, diagnosis and management of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: a revised statement from the ISSHP. Pregnancy Hypertens 2014;4:97–104.

- Drost JT, Arpaci G, Ottervanger JP, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors in women 10 years post early preeclampsia: the Preeclampsia Risk EValuation in FEMales study (PREVFEM). Eur J Prev Cardiol 2012;19:1138–44.

- Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD, Williams DJ. Pre-eclampsia and risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer in later life: systematic review and meta-analysis. Brit Med J 2007;335:974–7.

- Ahmed R, Dunford J, Mehran R, et al. Pre-eclampsia and future cardiovascular risk among women: a review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:1815–22.

- Mannisto T, Mendola P, Vaarasmaki M, et al. Elevated blood pressure in pregnancy and subsequent chronic disease risk. Circulation 2013;127:681–90.

- Chen CW, Jaffe IZ, Karumanchi SA. Pre-eclampsia and cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Res 2014;101:579–86.

- McDonald SD, Malinowski A, Zhou Q, et al. Cardiovascular sequelae of preeclampsia/eclampsia: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Am Heart J 2008;156:918–30.

- Bushnell C, McCullough LD, Awad IA, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in women: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2014;45:1545–88.

- Everson-Rose SA, Lewis TT. Psychosocial factors and cardiovascular diseases. Ann Rev Public Health 2005;26:469–500.

- Perk J, De Backer G, Gohlke H, et al. European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (version 2012). The Fifth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts). Eur Heart J 2012;33:1635–701.

- Kraemer HC, Stice E, Kazdin A, et al. How do risk factors work together? Mediators, moderators, and independent, overlapping, and proxy risk factors. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:848–56.

- Postma IR, Bouma A, Ankersmit IF, Zeeman GG. Neurocognitive functioning following preeclampsia and eclampsia: a long-term follow-up study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014;211:37 e1–9.

- Stramrood CA, Wessel I, Doornbos B, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder following preeclampsia and PPROM: a prospective study with 15 months follow-up. Reprod Sci 2011;18:645–53.

- Delahaije DH, Dirksen CD, Peeters LL, Smits LJ. Anxiety and depression following preeclampsia or hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets syndrome. A systematic review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2013;92:746–61.

- Gaugler-Senden IP, Duivenvoorden HJ, Filius A, et al. Maternal psychosocial outcome after early onset preeclampsia and preterm birth. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2012;25:272–6.

- Blom EA, Jansen PW, Verhulst FC, et al. Perinatal complications increase the risk of postpartum depression. The Generation R Study. BJOG 2010;117:1390–8.

- Baecke M, Spaanderman ME, van der Werf SP. Cognitive function after pre-eclampsia: an explorative study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 2009;30:58–64.

- Brussé I, Duvekot J, Jongerling J, et al. Impaired maternal cognitive functioning after pregnancies complicated by severe pre-eclampsia: a pilot case-control study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2008;87:408–12.

- Engelhard IM, van Rij M, Boullart I, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder after pre-eclampsia: an exploratory study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2002;24:260–4.

- Drost JT, Maas AH, Holewijn S, et al. Novel cardiovascular biomarkers in women with a history of early preeclampsia. Atherosclerosis 2014;237:117–22.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606–13.

- Lowe B, Decker O, Muller S, et al. Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care 2008;46:266–74.

- Michielsen HJ, De Vries J, Van Heck GL. Psychometric qualities of a brief self-rated fatigue measure: The Fatigue Assessment Scale. J Psychosom Res 2003;54:345–52.

- Arrindell WA, Schaap C. The Maudsley Marital Questionnaire (MMQ): an extension of its construct validity. Br J Psychiatry 1985;147:295–9.

- Russell D, Peplau LA, Cutrona CE. The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. J Pers Soc Psychol 1980;39:472–80.

- Scheier MF, Carver CS. Optimism, coping, and health: assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychol 1985;4:219–47.

- Denollet J. DS14: standard assessment of negative affectivity, social inhibition, and Type D personality. Psychosom Med 2005;67:89–97.

- Lakens D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: a practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front Psychol 2013;4:863.

- Zaiontz C. Effect Size for Chi-square Test 2016. Kramer’s V as an effect size. Available from: http://www.real-statistics.com/chi-square-and-f-distributions/effect-size-chi-square/ Access date 05 February 2016.

- Valkanova V, Ebmeier KP. Vascular risk factors and depression in later life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry 2013;73:406–13.

- Player MS, Peterson LE. Anxiety disorders, hypertension, and cardiovascular risk: a review. Int J Psychiatry Med 2011;41:365–77.

- Meng L, Chen D, Yang Y, et al. Depression increases the risk of hypertension incidence: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J Hypertens 2012;30:842–51.

- Badenhorst W, Hughes P. Psychological aspects of perinatal loss. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2007;21:249–59.

- Kersting A, Wagner B. Complicated grief after perinatal loss. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2012;14:187–94.

- Turton P, Evans C, Hughes P. Long-term psychosocial sequelae of stillbirth: phase II of a nested case-control cohort study. Arch Womens Ment Health 2009;12:35–41.