Abstract

Introduction: Isolated limb perfusion (ILP) is a treatment option most commonly used in the treatment of melanoma in-transit metastases of the extremities. The principle idea is to surgically isolate a region of the body and then deliver a high concentration of a chemotherapeutic agent together with hyperthermia. There have been three randomised trials exploring whether adjuvant ILP to patients with recurrent or high-risk primary melanomas increases survival; one of these trials has now been updated with a 25-year follow-up.

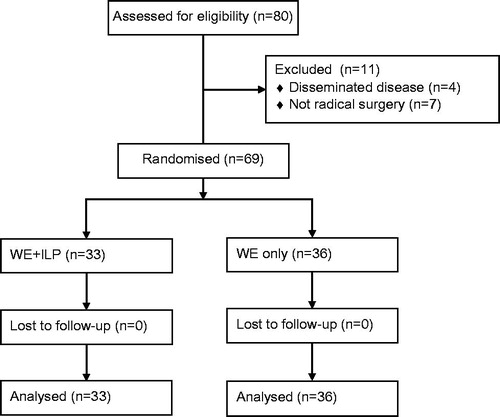

Methods: The original study randomised 69 patients (between 1981 and 1989) with their first satellite or in-transit recurrence to either wide excision (WE group, n = 36 patients) or to WE and adjuvant ILP (WE + ILP group, n = 33 patients). Follow-up data 25 years later concerning survival and cause of death was retrieved from the Swedish National Cause of Death Register.

Results: In the WE + ILP group there were 20 deaths (61%) due to melanoma compared with 26 deaths (72%) in the WE group (p = 0.31). Median melanoma-specific survival was 95 months for WE + ILP compared to 38 months for the WE group, an almost 5 year benefit without statistical significance (p = 0.24).

Discussion: There is no evidence that adjuvant ILP prolongs survival in patients with high-risk or recurrent melanoma; however, the existing randomised trials are largely underpowered to detect such a difference. New studies are exploring systemic immunological effects of ILP, and a combination of regional therapy and immunotherapy may serve as a rationale for new trials using ILP in the future.

Introduction

Approximately 5–10% of patients with high-risk melanoma will develop in-transit metastases, a form of tumour spread within intradermal and subcutaneous lymphatic channels [Citation1]. The initial treatment option considered is surgical excision, but when there are numerous lesions or short intervals between the appearances of new lesions, one treatment option is isolated limb perfusion (ILP). The technique was developed in the late 1950s, and the principle idea is to surgically isolate a region of the body and under hyperthermia deliver a high concentration of a chemotherapeutic agent to the tumour, while avoiding systemic toxicity [Citation2]. The results after ILP show a complete response (CR) rate between 60–70% and an additional 20% of the patients having a partial response [Citation3]. There have been three randomised trials exploring whether adjuvant ILP increases survival in patients with recurrent or high-risk melanomas.

The first study by Ghussen et al. was reported in 1984 and included 107 patients with both high-risk primary tumours as well as local recurrences [Citation4,Citation5]. The patients were randomised to either wide excision or wide excision with adjuvant ILP using melphalan. All patients had regional lymphadenectomy. After almost a 6-year median observation time there were 26 recurrences in the control group compared with six recurrences in the ILP group. They also reported an overall survival benefit with 11 patients dying from melanoma in the control group compared with three patients in the ILP group. This study has been criticised mainly for the unusually poor outcome in the control arm; patients with stage I disease randomised to the control group had a local recurrence rate of almost 50% [Citation6].

The second study, published 1998 by Koops et al., was a large randomised multi-centre trial including 832 patients with primary cutaneous melanoma >1.5 mm in thickness randomised to either wide excision or wide excision and adjuvant ILP with melphalan. Fifty-six per cent of the patients had no regional lymphadenectomy. The result showed a significant decrease in the occurrence of in-transit metastases, which were reduced from 6.6% to 3.3%. However, there was no benefit from ILP in terms of time to distant metastasis or survival [Citation7].

The third study, by Hafström et al., was published 1991 and included 69 patients with their first satellite/in-transit recurrence after wide resection of the primary melanoma. The patients were randomised to a wide re-excision (WE group) or WE and adjuvant ILP with melphalan (WE + ILP). The results showed an increased disease-free survival (DFS) with 7 months (17 vs. 10 months), but no significant difference in overall survival (35 vs. 57 months) [Citation8].

We have now conducted a 25-year follow-up of the randomised trial by Hafström et al. with the aim of determining whether there is a long-term survival advantage of adjuvant ILP.

Materials and methods

The original study included 80 patients between 1981 and 1989 with recurrent malignant melanoma of the extremities [Citation8]. Of these, four patients were excluded due to disseminated disease, and seven patients due to not having a radical surgery of the recurrence. The remaining 69 patients were randomly allocated to WE (n = 36) or WE + ILP (n = 33) with stratification for upper or lower extremity localisation (). All patients had either ilio-inguinal or axillary lymphadenectomy performed, if it had not been previously done. Patient characteristics are listed in .

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

In summary, ILP was performed by isolation and cannulation of the external iliac vessels for the lower extremity and the axillary vessels for the upper extremity. The cannulas were then connected to an oxygenator, a pump, and a heat exchanger. The temperature of the inflow perfusate was between 41.5 °C and 41.8 °C, and temperature was measured subcutaneously and intramuscularly with a mean temperature of 41.3 °C. The perfusate contained 450 mL fresh tapped blood and 700 mL of low molecular weight dextran (Rheomacrodex, Kabi-Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) and the flow rate was maintained between 500 and 700 mL/min. When the extremity temperature reached 40 °C, melphalan (Alkeran, Wellcome Foundation, London, UK) was added via the pump reservoir to the perfusion circuit at a dose of 0.45 mg/kg body weight for the upper extremity and 0.9 mg/kg body weight for the lower extremity. Half of the dose was administered initially, and the remaining half after 60 min of perfusion. After a total perfusion time of 120 min, the extremity was perfused with 500 to 1000 mL of low molecular weight dextran (Rheomacrodex) [Citation8].

The current follow-up data concerning survival and cause of death was retrieved from the Swedish National Cause of Death Register (Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare), which includes information about all deaths among Swedish residents, whether occurring in Sweden or abroad, with a coverage of more than 98% [Citation9]. Survival estimates were made according to the Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test, and between-groups comparison used the Pearson’s chi-squared test. The data was analysed using the GraphPad Prism 6 statistical software package (GraphPad Software, CA).

Results

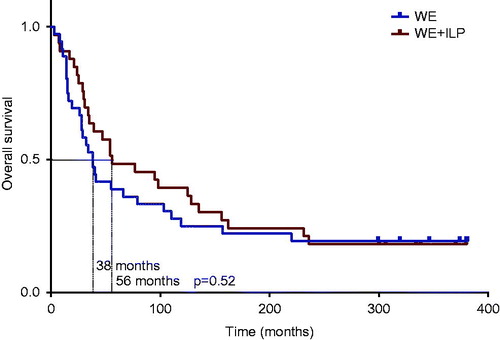

With more than 25 years of possible observation time after randomisation there was no significant difference in overall survival. In the WE group there were 29 deaths (81%) and in the WE + ILP group there were 27 deaths (82%). The median overall survival was 38 months for the WE group compared to 56 months for the WE + ILP group (), a non-significant difference of 18 months (p = 0.52).

Figure 2. Overall survival. Median overall survival was 56 months for the ILP group compared to 38 months for the control group (p = 0.52 log-rank test).

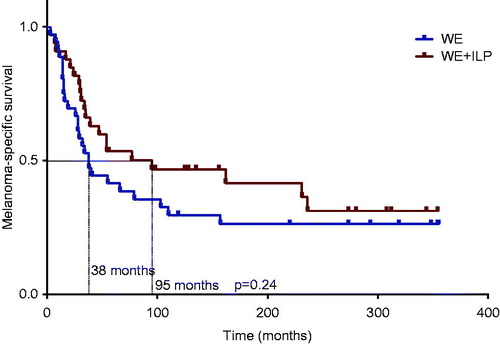

In the WE group there were 26 deaths (72%) due to melanoma compared with 20 deaths (61%) in the WE + ILP group (p = 0.31). Median melanoma-specific survival was 38 months for the WE group compared to 95 months for the WE + ILP group (), a difference of 57 months, however without statistical significance (p = 0.24).

Figure 3. Melanoma-specific survival. Median melanoma-specific survival was 95 months for the ILP group compared to 38 months for the control group (p = 0.24 log-rank test).

In the WE + ILP group there were four deaths due to other cancers (colon cancer, oesophageal cancer and two lymphomas), but notably only one death due to other cancer in the WE group (urinary bladder cancer).

Discussion

In the current update of the Hafström trial, the observed melanoma-specific survival difference of 57 months was not statistically significant. The one common problem among the existing randomised trials is the lack of power to detect a survival difference in the population that potentially has the most to gain – patients with in-transit metastases without evidence of distant metastases. In the Ghussen trial there were only 42 patients with recurrent melanoma, in the WHO study there were theoretically 55 patients (6.6% with in-transit metastases out of the total 832 patients) and in the Hafström trial 69 patients.

The main difference in melanoma-specific survival was observed within 5 years after randomisation, implicating that ILP might have altered the tumour biology in the patients having a more aggressive disease. Several studies have demonstrated a survival benefit in patients with CR after ILP, probably due to a more beneficial tumour biology in the group of patients responding to ILP [Citation10–12]. However, it cannot be completely excluded that elimination of microscopic disease may change the metastatic process, an argument similar to the proposed benefit of removing occult regional lymph node metastases in patients with positive sentinel node. In a subgroup analysis of patients with nodal metastases in the MSLT-1 trial, there was an improved distant disease-free and cancer-specific survival in patients with immediate lymph node removal, indicating that micro metastases might have a biological significance. However, when all patients were analysed, the trial failed to show any benefit in the primary endpoint of cancer-specific survival, raising questions about the clinical significance of sentinel node biopsy except as a staging procedure [Citation13].

Another possible explanation for the beneficial effect of ILP is that the treatment might give rise to an immunological activation. It is interesting to note that the clinical response after ILP can be quite slow, it may take well up to 3 months before a CR is reached, a finding that could be explained by systemic immunological processes. In a pilot study of ours, there was an increase in Melan-A-specific CD8+ T-cells four weeks after ILP, and also the preoperative levels of three different T-cell subsets seemed to be predictive for response, indicating that immunological reactions might be important [Citation14]. To our knowledge, any abscopal effects of ILP have not been reported, but recently there was a case report of a patient who received local radiation therapy against spinal metastases during treatment with the CTLA-4 antibody ipilimumab. After radiation there was also a size reduction in other metastasis, and this abscopal effect could also be correlated to changes in immunological parameters [Citation15].

If different regional treatment modalities such as radiation, electrochemotherapy or ILP can give rise to an immunological activation, combination treatments with new immunomodulatory drugs such as ipilimumab become even more interesting [Citation16,Citation17]. A randomised trial of ipilimumab with or without local radiation is currently recruiting patients (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01689974). In another phase II trial, patients with unresectable extremity melanomas receive ipilimumab 1–3 weeks after ILI with melphalan and dactinomycin (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01323517). If these, or other similar trials, can show an enhanced systemic immune activation after regional therapy, this may serve as a rationale for a new adjuvant trial using isolated limb perfusion and systemic immunotherapy in the future.

The major limitation of the original randomised trial is that with only 69 patients included, there is a low statistical probability to detect a survival benefit. The data concerning cause of death in this update is derived from the Swedish Cause of Death Register, with no patients missing and with the register having a high reliability.

Taken together, there is no conclusive evidence that adjuvant ILP prolongs survival in patients with high-risk or recurrent melanoma, and with current knowledge adjuvant ILP cannot be recommended. A potential survival benefit of almost 5 years is clearly clinically relevant, but this finding would have to be verified in a larger randomised trial, and unfortunately it is very unlikely that such a trial using only ILP would ever be initiated. However, if the immunological effects of regional therapies could be further elucidated, a combination with immunotherapy might very well be the basis for a new randomised adjuvant trial using ILP in the future.

Declaration of interest

This study was kindly supported by the Göteborg Medical Society and the Sahlgrenska Hospital Foundation for Medical Research, Gothenburg, Sweden. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Pawlik TM, Ross MI, Johnson MM, Schacherer CW, McClain DM, Mansfield PF, et al. Predictors and natural history of in-transit melanoma after sentinel lymphadenectomy. Ann Surg Oncol 2005;12:587–96

- Creech O Jr, Krementz ET, Ryan RF, Winblad JN. Chemotherapy of cancer: Regional perfusion utilizing an extracorporeal circuit. Ann Surg 1958;148:616–32

- Moreno-Ramirez D, de la Cruz-Merino L, Ferrandiz L, Villegas-Portero R, Nieto-Garcia A. Isolated limb perfusion for malignant melanoma: Systematic review on effectiveness and safety. Oncologist 2010;15:416–27

- Ghussen F, Kruger I, Smalley RV, Groth W. Hyperthermic perfusion with chemotherapy for melanoma of the extremities. World J Surg 1989;13:598–602

- Ghussen F, Nagel K, Groth W, Muller JM, Stutzer H. A prospective randomized study of regional extremity perfusion in patients with malignant melanoma. Ann Surg 1984;200:764–8

- Monson JR, Donohue JH. Long-term results of a randomized trial of hyperthermic limb perfusion (HLP) with chemotherapy for extremity melanoma. World J Surg 1990;14:845–6

- Koops HS, Vaglini M, Suciu S, Kroon BB, Thompson JF, Gohl J, et al. Prophylactic isolated limb perfusion for localized, high-risk limb melanoma: Results of a multicenter randomized phase III trial. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Malignant Melanoma Cooperative Group Protocol 18832, the World Health Organization Melanoma Program Trial 15, and the North American Perfusion Group Southwest Oncology Group-8593. J Clin Oncol 1998;16:2906–12

- Hafstrom L, Rudenstam CM, Blomquist E, Ingvar C, Jonsson PE, Lagerlof B, et al. Regional hyperthermic perfusion with melphalan after surgery for recurrent malignant melanoma of the extremities. Swedish Melanoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol 1991;9:2091–4

- Socialstyrelsen. Causes of Death 2012. Available from: http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/publikationer2013/2013-8-6

- Grunhagen DJ, Brunstein F, Graveland WJ, van Geel AN, de Wilt JH, Eggermont AM. One hundred consecutive isolated limb perfusions with TNF-alpha and melphalan in melanoma patients with multiple in-transit metastases. Ann Surg 2004;240:939–47; discussion 47–8

- Noorda EM, Vrouenraets BC, Nieweg OE, van Geel BN, Eggermont AM, Kroon BB. Isolated limb perfusion for unresectable melanoma of the extremities. Arch Surg 2004;139:1237–42

- Alexander HR Jr, Fraker DL, Bartlett DL, Libutti SK, Steinberg SM, Soriano P, et al. Analysis of factors influencing outcome in patients with in-transit malignant melanoma undergoing isolated limb perfusion using modern treatment parameters. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:114–18

- Morton DL, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, Mozzillo N, Nieweg OE, Roses DF, et al. Final trial report of sentinel-node biopsy versus nodal observation in melanoma. N Engl J Med 2014;370:599–609

- Olofsson R, Lindberg E, Karlsson-Parra A, Lindner P, Mattsson J, Andersson B. Melan-A specific CD8+ T lymphocytes after hyperthermic isolated limb perfusion: A pilot study in patients with in-transit metastases of malignant melanoma. Int J Hyperthermia 2013;29:234–8

- Postow MA, Callahan MK, Barker CA, Yamada Y, Yuan J, Kitano S, et al. Immunologic correlates of the abscopal effect in a patient with melanoma. N Engl J Med 2012;366:925–31

- Jure-Kunkel M, Masters G, Girit E, Dito G, Lee F, Hunt JT, et al. Synergy between chemotherapeutic agents and CTLA-4 blockade in preclinical tumor models. Cancer immunol immunother 2013;62:1533–45

- Gerlini G, Sestini S, Di Gennaro P, Urso C, Pimpinelli N, Borgognoni L. Dendritic cells recruitment in melanoma metastasis treated by electrochemotherapy. Clin Exp Metastasis 2013;30:37–45