Abstract

Objective: The aim of this paper was to retrospectively compare the therapeutic efficacy and adverse effects of ultrasound-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound (USgHIFU) treatment for adenomyotic patients with or without prior abdominal surgical scars. Methods: From January 2011 to March 2014, 534 patients with adenomyosis were referred for HIFU treatment. Among them, 118 patients had prior abdominal surgical scars, 416 patients did not have prior abdominal surgical scars. Contrast-enhanced MRI was used to evaluate the treatment outcomes. All the adverse effects were recorded. Results: All patients completed USgHIFU treatment. A fractional ablation of 74.8 ± 27.8% was achieved in the group of patients without abdominal scars; the fractional ablation was 75.6 ± 22.3% in the group of patients with prior abdominal surgical scars. No significant difference in fractional ablation between the two groups was observed (p > 0.05). The rate of skin burn in the group of patients with prior abdominal surgical scars was significantly higher than that in the group without abdominal scars (2.5% vs. 0.2%, p < 0.05), but it is still acceptable. Conclusion: The prior abdominal surgical scars have no significant influence on the effectiveness of HIFU treatment for adenomyosis. The risk of skin burn is higher in patients with abdominal scars than without, but the incidence rate is still acceptable.

Introduction

Adenomyosis is a common benign condition of the uterus in women of reproductive age that causes painful menstruation and/or heavy menstruation bleeding in about two thirds of patients [Citation1,Citation2]. This disease may also reduce the pregnancy rate for women [Citation3,Citation4]. Currently, hysterectomy is still the only definitive treatment for patients with symptomatic adenomyosis. However, this invasive surgical treatment is not appropriate in adenomyotic patients who wish to remain fertile or preserve the uterus. Since the adenomyotic lesion is often ill-defined, conservative surgery has proven to be effective only in around 50% of patients and with a high recurrence rate [Citation5]. Over the last few years, uterine artery embolisation (UAE) has been used to treat this disease and the results showed that UAE is effective in treating symptomatic adenomyosis [Citation6]. Many studies have also shown that conservative treatments including use of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (IUD), gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues (GnRHa), and oral contraceptives, as well as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) were able to alleviate symptoms associated with adenomyosis. However, the side effects of these treatments and the high recurrence after medical therapy cessation have limited the effects for these treatments [Citation7]. Therefore, the treatment for adenomyosis is always a challenge to clinicians.

Recently, high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU), a novel technology, has been used to treat patients with symptomatic adenomyosis. Several studies have examined the safety profile of USgHIFU and MR-guided focused ultrasound (MRgFUS) in treating patients with this disease [Citation8–11]. However, the use of MRgFUS was not recommended in treating patients with uterine fibroids and abdominal scars because of the increased risk of skin burns [Citation12–14]. To the best of our knowledge, no author has reported the USgHIFU therapeutic results of patients with adenomyosis and abdominal scars. In this study we retrospectively compared the efficacy and adverse effects of USgHIFU treatment for patients with adenomyosis and abdominal surgical scars to those with adenomyosis but without abdominal scars to explore whether and how USgHIFU can be safely used to treat adenomyotic patients who have abdominal scars.

Materials and methods

The present study was a retrospective observational study. The ethics committees at our institutions approved the protocol and every patient signed an informed consent before the procedure.

Patients

From January 2011 to March 2014, 534 patients with adenomyosis were treated with HIFU in Suining Central Hospital of Sichuan. The diagnosis of adenomyosis was suspected by clinical evaluation and confirmed with ultrasound and MRI. The diagnostic criteria used in this study include focal or diffuse thickening of the uterine junctional zone or the presence of a low signal intensity myometrial mass with ill-defined borders [Citation15,Citation16]. All the patients had menstruation pain and/or heavy bleeding. Among them, 118 patients had prior abdominal surgical scars and 416 had no abdominal wall scars. Of the 118 patients who had prior abdominal surgical scars, 88 patients had caesarean sections, 21 patients had myomectomies, 9 patients had other surgeries. The horizontal scar was seen in 53 patients, while the vertical scar was observed in 65 patients. The average size of the scars was 5.6 ± 2.2 mm in width and 125.3 ± 26.5 mm in length. The average age of patients with prior abdominal surgical scars was 41.7 ± 6.8 years, while the average age of patients without prior abdominal surgical scars was 43.1 ± 6.6 years ().

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the adenomyotic patients with or without abdominal scars.

Pretreatment preparation

Following the approved protocol, all patients were requested to have specific bowel preparation 3 days prior to HIFU treatment. On the morning of the treatment day, the skin from the umbilicus level to the upper margin of the pubic symphysis was carefully shaved, degreased and degassed before treatment. A urinary catheter was inserted to control the bladder volume through injection of normal saline. In addition, a degassed water balloon was used to compress and push bowels away from the acoustic pathway to prevent intestine lesion.

High-intensity focused ultrasound ablation

All HIFU treatments were performed with the ultrasound-guided JC200 system (Haifu® Technology, Chongqing, China). The ultrasound device (MyLab 70, Esaote, Genoa, Italy), which provides real-time guidance, was located at the centre of the transducer. A focused transducer, 20 cm in diameter with a frequency at 1.0 MHz, was located in a water tank.

Immediately before treatment, every patient was optimally positioned prone on the HIFU table. A water balloon filled with cold degassed water was placed between the transducer and the anterior abdominal wall. In order to decrease the risk of skin burn, the temperature of the degassed water in the water tank was set below 20 °C and the abdominal wall was in contact with the cold degassed water.

The treatment was performed under conscious sedation. Patients received fentanyl (50–400 μg) and midazolam hydrochloride (1–4 mg) to reduce discomfort, and prevent movement. The respiration, heart rate, blood pressure, and oxygen saturation level were tracked and every patient was requested to report any discomfort or pain to an assisting nurse during the procedure.

In order to observe the positional relationship between the lesion and the bowel, HIFU treatment was performed under the sagittal ultrasound scanning mode. A point scan with 350–400 W of sonication power was used, and when the hyperechoic region covered the entire treated lesion, the treatment terminated. Then, contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) was performed to assess the ablation results. If any unexpected residual lesion was noted, an additional HIFU ablation in the same session of HIFU treatment was performed. During HIFU treatment, occurrence of leg pain, sciatic/buttock pain, lower abdominal pain, and ‘hot’ skin sensation were recorded. Immediately after the procedure, any pain or any change to the skin was also recorded.

Magnetic resonance imaging evaluation

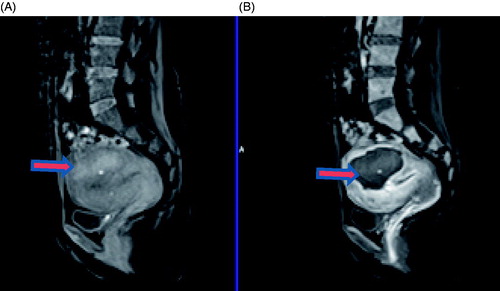

Following our clinical guideline, contrast-enhanced MRI was used to evaluate the ablation effects (). All patients were requested to havean MRI before and one day after HIFU treatment. All MRI examinations were performed using a 1.5-T Magnetom Symphony MR unit (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany). The parameters used for T1-weighted imaging (T1WI) were as follows: TR 502/TE 12 ms, field of view 230 × 230 mm, slice thickness 4 mm. Typical parameters used for T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) were as follows: TR 4000/TE 98 ms, field of view of 230 × 230 mm, and a slice thickness of 4 mm. The contrast-enhanced MRI sequence began immediately after intravenous injection of gadolinium (Omnisca, GE Healthcare, Cork, Ireland, dose: 0.1 mmol/kg body weight) with the following parameters: TR 5.13/TE 2.37 ms, field of view 350 × 262 mm, and a slice thickness of 2.5 mm. Two radiologists with 5 years of experience compared the pre- and post-treatment MRI images. The size of the targeted lesions and non-perfused regions were measured using the software programmed by Chongqing Haifu Medical Technology; the fractional ablation, defined as the non-perfused volume divided by the lesion volume, was calculated.

Figure 1. Contrast enhanced MR images obtained from a 45-year-old patient with adenomyosis. (A) Pre-procedure MRI shows a 4.9 × 4.8 × 3.3 cm adenomyotic lesion located at the posterior wall of the uterus (arrow). (B) Contrast-enhanced MRI obtained 1 day after HIFU shows the fractional ablation was 90.8% (arrow).

Statistical analysis

Data are reported as the mean ± SD. SPSS 17.0 (IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL) was used for data analysis. Mann-Whitney rank sum test was used for statistical comparisons of lesion volume as well as total sonication time between the patients with prior abdominal surgical scars and without. The χ2 test was used for statistical comparisons of the incidence of adverse events. A p value below 0.05 was considered to indicate a significant difference.

Results

Patients’ demographic characteristics

shows the baseline demographic characteristics of the patients involved in this study. The average volume of the uterus was 223.1 ± 110.6 cm3 in the patients without abdominal scars and 206.5 ± 100.6 cm3 in the patients with prior abdominal surgical scars. Based on the MR images, in the group of patients without prior abdominal surgical scars, 38.9% of the adenomyotic lesions were at the anterior wall of the uterus, 49.5% of them were located at the posterior wall, 7.5% of the lesions were at the fundus, and 4.1% of the lesions were at the lateral wall of the uterus. In the patients with prior abdominal surgical scars, 32.2% of the adenomyotic lesions were seen at the anterior wall of the uterus, 59.3% of them were observed at the posterior wall, 5.1% of the lesions were at the fundus and 3.4% of the lesions were at the lateral wall of the uterus. Based on MRI T2WI, in the group of 416 patients without abdominal scars, 7.5% of the lesions were classified as hyperintensity, 59.9% of the lesions were classified as isointensity, and 32.7% of the lesions were classified as hypointensity. In the group of patients with prior abdominal surgical scars, 6.8% of the lesions were classified as hyperintensity, 65.3% of the lesions were classified as isointensity, 28.0% of the lesions were classified as hypointensity. The thickness of the fat tissue on abdominal wall averaged 20.6 ± 8.7 mm in the group of patients without prior abdominal surgical scars and 18.6 ± 8.6 mm in the group of patients with prior abdominal surgical scars. No significant difference in demographics and baseline characteristics was observed between the two groups.

Peri- and post-HIFU evaluations

shows the HIFU treatment sonication power, HIFU sonication time, sonication time per hour, sonication energy used, and the treatment results of the patients with or without prior abdominal surgical scars. With the usage of similar sonication power, sonication time, and total energy to treat similar lesion volumes, a fractional ablation of 74.8 ± 27.8% was achieved in the group of patients without abdominal scars; the fractional ablation was 75.6 ± 22.3% in the group of patients with prior abdominal surgical scars. No significant difference in sonication power, sonication time, total energy used, lesion volume, NPV and fractional ablation was observed between the two groups. However, the sonication time/hour was significantly less in the group of patients with prior abdominal surgical scars than that of patients without prior abdominal surgical scars (p = 0.032).

Table 2. Treatment results of HIFU for patients with or without abdominal scars.

Adverse effects and complications

Every patient was requested to report any pain or discomfort during the HIFU procedure. All patients were checked for adverse effects or complications immediately after HIFU treatment. Following the approved protocol by our institute, every patient was called daily to inquire about any discomfort during the first 3 days after the procedure, and all women returned after 1 month for follow-up of complications and adverse effects.

The transient leg pain, sciatic/buttock pain, lower abdominal pain, or ‘hot’ skin sensation was often observed during the procedure. In this study, the lower abdominal pain was the most often seen adverse effect. Sciatic/buttock pain was often seen in patients with lesions located at the posterior wall of the uterus, and leg pain was often observed in patients with an adenomyotic lesion located at the lateral wall or the fundus. The ‘hot’ skin sensation is a unique adverse effect of HIFU and patients with abdominal scars more frequently reported this discomfort. However, no significant difference in incidence rates of these adverse effects between the two groups was observed ().

Table 3. Incidence rates of adverse effects during the HIFU procedure.

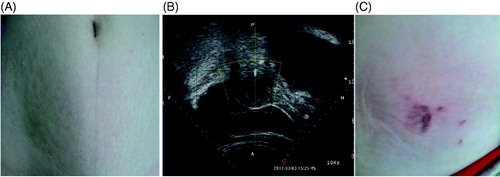

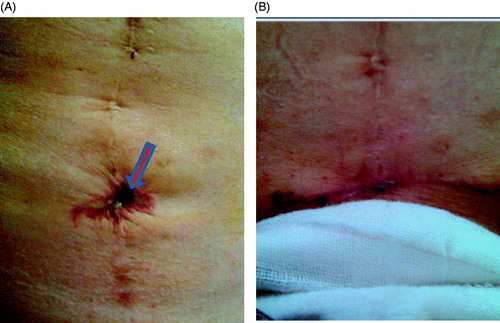

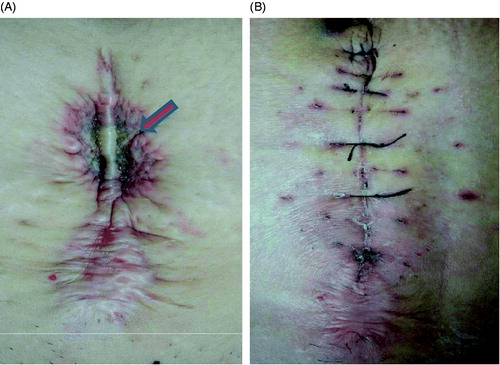

shows the incidences of the adverse effects and complications immediately after HIFU. The lower abdominal pain was the most common post-HIFU adverse effect. However, the pain score was often less than 4 points and often disappeared within 3 days. The vaginal discharge was another common adverse effect after HIFU treatment and it subsided in 7 days for most patients, with a few cases that lasted for 1 month. In this study, the post-procedure leg pain and sciatic/buttock pain were rare, and all of the pain disappeared in 1 week. No significant difference was observed in the rates of post-HIFU adverse effects including fever, lower abdominal pain, sciatic pain/buttock pain, leg pain, and vaginal discharge between the patients with or without prior abdominal surgical scars. However, the rate of skin burn was significantly higher in patients who had abdominal scars than those without (p = 0.035), of whom, two (3.1% of) patients with prior vertical abdominal surgical scars and one (1.9%) with a horizontal scar had deep second or third degree skin burns, while only one out of 416 (0.2%) in the group of patients without prior abdominal surgical scars had a superficial second degree skin burn (). Three patients with deep second or third degree skin burns had surgical resection to remove the burned tissue ( and ). Based on the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), all these effects except second and third degree skin burns were classified as grade 1, while second and third degree skin burns were classified as grade 2 adverse effects [Citation17].

Figure 2. Real-time ultrasound image and pictures from a 42-year-old adenomyotic patient without abdominal scar. (A) A pre-HIFU picture shows no scar on abdominal wall. (B) Real-time ultrasound image shows the retroposition of the uterus. The adenomyotic lesion is located at posterior wall of the uterus. During HIFU, the bladder was filled with normal saline and a degassed water balloon was used to push away the bowel. (C) A picture obtained 1 day after HIFU shows the blisters. The blisters subsided in 10 days.

Figure 3. Pictures obtained from a 45-year-old adenomyotic patient with abdominal scar. (A) A picture obtained 2 days after HIFU shows a small area of third degree of skin burn on the surgical scar (arrow); the size of the burnt area was 1.0 × 1.5 cm (arrow). (B) Picture obtained two weeks after HIFU shows the burnt skin had been resected.

Figure 4. Pictures obtained from a 47-year-old patient with adenomyosis and abdominal scar. (A) A picture obtained immediately after HIFU shows the third degree skin burn on the surgical scar (arrow); the size of the burnt area was 1.5 × 2.0 cm (arrow). B. A picture obtained 10 days after HIFU shows the burnt skin had been resected along the abdominal scar.

Table 4. Incidence rates of adverse effects and complications immediately after HIFU treatment.

Discussion

As a promising technique, HIFU has been used to treat adenomyosis for years [Citation8–11]. Recently, more and more gynaecologists in China have considered USgHIFU to be a routine treatment for patients with adenomyosis. The 3- to 12-month follow-up results showed that the clinically effective rates for dysmenorrhoea or menorrhagia were around 80% [Citation9,Citation11]. With the increased caesarean section rate and the recurrent nature of adenomyosis, in clinical practice more and more patients with adenomyosis who had prior abdominal surgical scars were present in the clinic. In this study, among the 534 adenomyotic patients treated, 118 had prior abdominal surgical scars. Since scar tissue is less vascular and more fibrotic than normal tissue, it is difficult for ultrasound to penetrate the scars and the ultrasound energy is readily absorbed by the scar tissue, resulting in thermal increase. This might consequently affect the efficacy and safety of HIFU treatment. Several studies have shown that MRgFUS was not recommended in treating patients with uterine fibroids and abdominal scars because of the increased risk of skin burns [Citation12–14]. A prior study has described a method to aid in the visualisation and treatment of uterine fibroids with MRgFUS in patients with abdominal scars to avoid scar tissue obstructing the potential acoustic pathway. They highlighted scars on MR images by injection of paramagnetic iron oxide particles before the procedure of MRgFUS began [Citation18]. However, our results showed that USgHIFU can be safely used to treat patients with adenomyosis and surgical scars. USgHIFU may be preferred over MRgFUS in treating patients with abdominal surgical scars because the abdominal wall is in contact with cold degassed water during the procedure of USgHIFU treatment, while the abdominal wall is in contact with the gel pad during treatment with MRgFUS. The cold water could help to decrease the risk of skin burns. In the present study, patients with or without prior abdominal surgical scars had similar baseline characteristics (). Compared to the group of patients without prior abdominal surgical scars, by delivering similar sonication power, spending similar sonication time, and using the same amount of total energy with less sonication time/hour to ablate the adenomyotic lesions in the group of patients with abdominal scars (spent more time to cool down the skin), the average fractional ablation of 75.6 ± 22.3% was achieved, and no statistical significance in fractional ablation was observed between the two groups (). Our results demonstrated that the prior abdominal surgical scars seem to have no effect on the USgHIFU therapeutic efficacy. Therefore, it is not necessary to deliver more ultrasound energy to the adenomyotic lesions in the patients with prior abdominal surgical scars than that of patients without prior abdominal surgical scars to achieve similarly high fractional ablation.

In comparison with MRI, ultrasound has the advantage of visualising the scar. However, this is also a disadvantage in observing the target behind the scars. This may raise a concern about ‘missing the target’ because the monitoring ultrasound image behind the scar is not clear. However, our results did not show any of this kind of adverse effects or complications in the group of patients with prior abdominal surgical scars, and from our experience this visible ultrasound image of the scar can help reduce the risk of skin burn.

Our results also showed that patients both with or without abdominal scars tolerate the pain well. In this study patients often complained of transient leg pain, sciatic/buttock pain, lower abdominal pain, and ‘hot’ skin sensation during HIFU treatment for adenomyosis. Among these transient adverse effects, transient leg pain and sciatic/buttock pain were often related to the location of the lesions; local oedema of the treated region or uterus contraction may have caused the lower abdominal pain; ‘hot’ skin sensation seemed to be the only one associated with the prior abdominal surgical scars. Our results did not show a significant difference between the two groups in the rate of ‘hot’ skin sensation (). This can be explained either by a local sensory loss of skin around the scar or by the lower treatment intensity (less sonication time/hour) in the group of patients with prior abdominal surgical scars.

USgHIFU has been confirmed as a safe treatment for uterine fibroids and adenomyosis [Citation19,Citation20]. Immediately after HIFU treatment we observed the common adverse effects of lower abdominal pain, sciatic/buttock pain, and vaginal discharge. Based on CTCAE, all these effects except second and third degree skin burns were classified as grade 1, while second and third degree skin burns were classified as grade 2 of adverse effects [Citation17]. Based on the Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR) classification system for complications by outcome, these adverse effects were mild, and most of them subsided within 1 week without any therapy [Citation21]. We also observed that a few patients had leg pain after HIFU treatment because of the temporary sacral nerve irritation. We defined leg pain as a major adverse effect because it lasted over 2 weeks and NSAIDs were suggested for these patients. These adverse effects mentioned above were not related to abdominal scars and we did not find any significant differences between the patients with and without prior abdominal surgical scars. Although the rate of temporary ‘hot’ skin sensation during the USgHIFU procedure in patients with adenomyosis and abdominal scars was similar to the patients without abdominal scars, the incidence rate of skin burn was significantly higher in patients with abdominal scars than without (). In the patients without prior abdominal surgical scars, only one case had superficial second degree skin burn, and the incidence rate was 0.2%. In addition, from the group of patients with prior abdominal surgical scars, three out of 118 (2.5%) had deep second or third degree skin burns. All three cases had surgical resection to remove the burned tissue. Our results demonstrated that the patients with prior abdominal surgical scars have higher risk of skin burn occurrence than patients without abdominal scars because the scar tissue may have been denervated in some cases and the patients could have felt pain when the scars were heated, but the rate was still acceptable. We further reviewed the four patients with skin burns individually. The patient who had no prior surgical scars had a retroverted uterus and posterior uterine adenomyotic lesion (). During HIFU the bladder was filled with normal saline, and a degassed water balloon was placed on the abdominal wall to compress and push away the bowel; blisters occurred because of both inadequate coupling and compressing time (decompressing in every 100 s of sonication is recommended), resulting in heat generation. The blisters subsided in 10 days without any specific treatment. In the three patients who had prior abdominal surgical scars, all had deep either second or third degree skin burn, and surgical intervention was performed ( and ). Poor skin preparation, less blood supply for scar tissue, and skin sensory loss could explain the increased number and severity of skin burns in the patients with prior abdominal surgical scars. The rate of skin burn in patients with prior surgical scars can be further decreased by often checking the skin during HIFU treatment; moving the transducer down in the water tank and moving the degassed water balloon away from the acoustic pathway every 50 s of sonication to let the cold degassed water in contact with skin were techniques used to check. Therefore, with careful skin preparation, patients with adenomyosis and abdominal scars can be safely treated with USgHIFU. This study is limited because different doctors performed the HIFU procedures. Although the same protocol was followed in our centre, the different levels of experience of clinicians carrying out the treatments may have had an influence on the results. This study is also limited by the relatively small number in the group of patients with abdominal scars. In addition, we did not compare the incidence rates of skin burn in patients with different widths of prior abdominal surgical scars. Future studies to compare the rate of skin burn in patients with a variety of prior abdominal surgical scar widths will be important.

Conclusion

In summary, this study demonstrated that USgHIFU can be safely and effectively used to treat adenomyotic patients with or without prior abdominal surgical scars. The risk of skin burn is higher in patients with abdominal scars than without, but the incidence rate is still acceptable. With careful skin preparation, the rate of skin burn in patients with prior abdominal surgical scars can be further decreased by often moving the transducer down to decompress the abdominal wall or by checking the skin during HIFU treatment.

Declaration of interest

The study was partially supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (2011CB707900), the National Key Technology Research and Development Program (2011BAI14B01), the National Natural Science Fund by the Chinese National Science Foundation (81127901, 30830040, 31000435, 11274404) and Specialized Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education (20115503110008). Lian Zhang is a senior consultant for the Chongqing Haifu Company.

The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Taran FA, Stewart EA, Brucker S. Adenomyosis: Epidemiology, risk factors, clinical phenotype and surgical and interventional alternatives to hysterectomy. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 2013;73:924–31

- Seidman JD, Kjerulff KH. Pathologic findings from the Maryland Women’s Health Study: Practice patterns in the diagnosis of adenomyosis. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1996;15:217–21

- Leyendecker G, Kunz G, Kissler S, Wildt L. Adenomyosis and reproduction. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2006; 20:523–46

- Salim R, Riris S, Saab W, Abramov B, Khadum I, Serhal P. Adenomyosis reduces pregnancy rates in infertile women undergoing IVF. Reprod Biomed Online 2012; 25:273–7

- Wood C. Adenomyosis: Difficult to diagnose, and difficult to treat. Diagn Ther Endosc 2001;7:89–95

- Nijenhuis RJ, Smeets AJ, Morpurgo M, Boekkooi PF, Reuwer PJ, Smink M, et al. Uterine artery embolization for symptomatic adenomyosis with polyzene F-coated hydrogel microspheres: Three years clinical follow-up UFS-QOL questionnaire. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2015;38:65–71

- Wood C. Surgical and medical treatment of adenomyosis. Hum Reprod Update 1998;4:323–36

- Zhang L, Zhang W, Orsi F, Chen W, Wang Z. Ultrasound-guided high intensity focused ultrasound for the treatment of gynaecological diseases: A review of safety and efficacy. Int J Hyperthermia 2015;31:280–4

- Zhou M, Chen JY, Tang LD, Chen WZ, Wang ZB. Ultrasound-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound ablation for adenomyosis: the clinical experience of a single center. Fertil Steril 2011;95:900–5

- Fan TY, Zhang L, Chen W, He M, Huang X, Orsi F, et al. Feasibility of MRI-guided high intensity focused ultrasound treatment for adenomyosis. Eur J Radiol 2012;81:3624–30

- Zhang X, Li K, Xie B, He M, He J, Zhang L. Effective ablation therapy of adenomyosis with ultrasound-guided high intensity focused ultrasound. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2014;124:207–11

- Hindley J, Gedroyc WM, Regan L. MRI guidance of focused ultrasound therapy of uterine fibroids: Early results. Am J Roentgenol 2004;183:1713–19

- Leon-Villapalos J, Kaniorou-Larai M, Dziewulski P. Full thickness abdominal burn following magnetic resonance guided focused ultrasound therapy. J Burns 2005;31:1054–5

- Yoon SW. Patient selection guidelines in MR-guided focused ultrasound surgery of uterine fibroids. Eur Radiol 2008;18:2997–3006

- Sudderuddin S, Helbren E, Telesca M, Williamson R, Rockall A. MRI appearances of benign uterine disease. Clin Radiol 2014;69:1095–104

- Reinhold C, Tafazoli F, Wang L. Imaging features of adenomyosis. Hum Reprod Update 1998;4:337–49

- Trotti A, Colevas AD, Setser A, Rusch V, Jaques D, Budach V, et al. CTCAE v3.0: Development of a comprehensive grading system for the adverse events of cancer treatment. Semin Radiat Oncol 2003;13:176–81

- Zaher S, Gedroyc W, Lyons D, Regan L. A novel method to aid in the visualisation and treatment of uterine fibroids with MRgFUS in patients with abdominal scars. Eur J Radiol 2010;76:269–73

- Wang F, Tang L, Wang L, Wang X, Chen J, Liu X, et al. Ultrasound-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound vs laparoscopic myomectomy for symptomatic uterine myomas. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2014;21:279–84

- Wang W, Wang Y, Tang J. Safety and efficacy of high intensity focused ultrasound ablation therapy for adenomyosis. Acad Radiol 2009;16:1416–23

- Sacks D, McClenny TE, Cardella JF, Lewis CA. Society of interventional radiology clinical practice guidelines. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2003;14:S199–202