Abstract

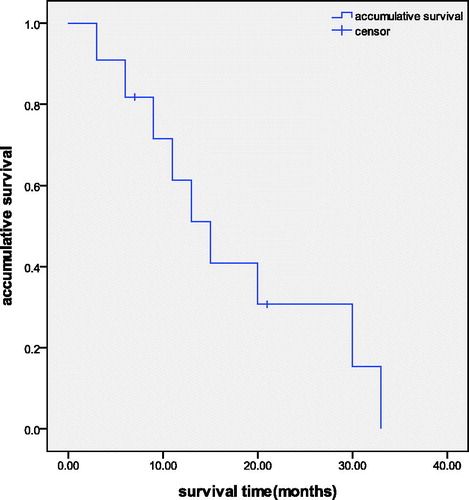

Purpose: This study was designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of microwave ablation (MWA) in the treatment of intrahepatic recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) after liver transplantation. Materials and methods: Between October 2008 and August 2014, a total of 11 cases with 19 lesions were enrolled. All the subjects had confirmed HCC recurrence after liver transplantation by at least two types of enhanced imaging. Real-time monitoring and small ethanol doses were used as an additional technique to assist with ablation. Contrast imaging was performed to evaluate the technique efficacy. The technique efficacy rate, local tumour progression rate, 3, 6, 9, 12, 18 and 24 months survival rates, and the incidence of complications were comprehensively analysed. Results: The follow-up period ranged from 5–33 months. All tumours achieved full ablation. The first MWA technique efficacy rate was 84.2% (16/19), while the second technique efficacy rate was 100%. Local tumour progression was identified in three cases (15.8%) at 1, 3 and 7 months after MWA. The 3, 6, 9, 12, 18 and 24 months accumulative survival rates were 90.9%, 81.8%, 71.6%, 51.5%, 30.7% and 15.3%, respectively, the average survival time was 17.3 months (3.5–33 months). Mild side effects included five patients (45.4%) with fevers, three with (27.3%) nausea and vomiting, five (45.4%) with local pain, and eight (72.7%) with increased blood transaminase levels; no serious complications occurred. Conclusion: MWA treatment is a promising technique for intrahepatic recurrence after liver transplantation without serious complications or side effects.

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the second leading cause of cancer death in less developed countries and the sixth leading cause of cancer death in more developed countries among men. About 782 500 new liver cancer cases and 745 500 deaths from HCC occurred worldwide during 2012, with China alone accounting for about 50% of the total number [Citation1]. At present, liver resection, orthotopic liver transplantation (LT) and thermal ablation are the most effective surgical treatment for patients with HCC. Most occurrences of HCC are known to be associated with liver cirrhosis, so LT is considered as the most ideal therapy for eliminating the existing tumours, the underlying liver cirrhosis and the risk of multicentric carcinogenesis that results from chronically injured liver [Citation2]. For the patients with HCC who conform to the Milan criteria and accepted liver transplantation from 1989 to 2001 in Germany, the five years survival rate after liver transplantation can achieve to 70%, 1, 3 and 5 years survival rate were 92.0%, 85.7% and 74.1%, and the disease-free survival rates were 87.5%, 81.3% and 87.5% respectively [Citation3]. However, with the expansion of the criteria of LT, tumour recurrence after transplantation is common, 70% of which occurs within the first 2 years after transplantation. The total incidence of metastases after LT is about 52.8%, and the average time of recurrence and metastasis is 198 ± 29 days [Citation4]. Moreover, most patients with recurrent tumours cannot tolerate surgical therapy [Citation5] again. Therefore, high recurrence rate after transplantation has become the main choke point affecting long-term survival. Microwave ablation (MWA) is a relatively new method of minimally invasive treatment which has been recognised by international authorities for its advantages such as minimal invasion, good curative effect, no radiation or chemotherapy side effects, and protection of the body's immune function, so has been widely used in the treatment of malignant tumours [Citation6,Citation7]. This study aims to assess the effectiveness, safety and clinical outcomes of US-guided MWA in treating intrahepatic recurrence of HCC after LT.

Materials and methods

Patients

The clinical information of 11 patients with intrahepatic recurrence of HCC after LT was analysed retrospectively. All the patients accepted MWA treatment between October 2008 and August 2014. The patients enrolled met the following inclusion criteria: 1) histologically confirmed HCC, 2) at least two types of enhanced image confirming intrahepatic recurrence, 3) unsuitable for radical resection or refused to undergo surgery, 4) free of contraindication of PMWA. Patients with portal vein embolus and limited life expectancy (less than 3 months) were excluded. Finally, 11 men with 19 tumours were enrolled, mean age 52.5 ± 4.7 years (range 40–66 years) and the mean diameter of tumours was 3.1 ± 1.5 cm. All the patients were taking immunosuppressants. The basic characteristic of the patients and tumours are shown in . The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Chinese PLA General Hospital, and written informed consent was obtained from each patient before MWA.

Table 1. Patient population and tumour characteristics.

Procedures

Preoperative evaluation

Intrahepatic recurrence of HCC after LT was confirmed by at least two types of enhanced images including contrast enhance ultrasound (CEUS), computed tomography (CT) or contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (CE-MRI). CEUS imaging (ACUSON, Sequoia, CA) before ablation was performed routinely to evaluate the size of the tumour, the blood supply in or around it, and the relationship between the tumour and surrounding structures, such as portal vein, biliary ducts, gallbladder or the gastrointestinal tract. The surgical planning was based on the imaging data and preoperative laboratory test results. All patients fasted from food and water for 12 h, and intravenous accesses were routinely established. For the patients accepted for biliary intestinal anastomosis, lactulose was used for the preoperative intestinal preparation.

Microwave ablation equipment and technique

Patients were treated with a MWA system (KY-2000, Kangyou Medical, Nanjing, China) that consisted of two microwave generators, two flexible coaxial cables and two cooled shaft antennas. The machine was able to emit 2450 MHz frequency and 1–100 W power. The needle antenna (15-gauge diameter, tip: 0.5 cm or 1.1 cm) was coated with polytetrafluoroethylene to avoid adhesion and the water cooled function was used. The number of needles chosen was based on the tumour size. For a tumour less than 1.5 cm, one antenna was sufficient; for tumours measuring 1.5 cm or more, two antennas were inserted. The distance between the two antennas was 1–2 cm.

Before MWA, US-guided biopsy was performed with an 18-gauge cutting needle. Intravenous anaesthesia was administered with propofol and ketamine for all patients. The process of MWA was monitored by real-time US. The output power was 40–60 W and lasted for 5–10 mins for one session. Technical success was defined as the target tumour being treated according to the protocol and the ablation zone completely covering the tumour and ablative margin. The minimum ablative margin was 5 mm [Citation8]. For the large tumour, multiple overlapping ablations were needed to obtain a safe margin. Finally, the needle track was ablated with sufficient microwave energy by quitting the cooling-shaft water dump. Vital signs were closely monitored by electrocardiogram during the MWA process.

Thermal monitoring

For tumours adjacent to potentially vulnerable structures, such as large vessels, biliary ducts, gallbladder or the gastrointestinal tract, a thermal monitoring system was used to avoid thermal injury. A 20-gauge thermocouple was put at the site of 5 mm away from the margin of tumour near to the potentially vulnerable tissue. Our experimental and clinical experience showed that temperatures of or 45–54 °C can induce coagulative necrosis thoroughly in tumours. However, if the temperature decreased to 45 °C or lower, then the MWA could not be considered activated sufficiently [Citation9].

Adjuvant small dose of ethanol therapy

For tumours adjacent to the potentially vulnerable parts mentioned above, it is very difficult to create an extensive ablative margin, so adjuvant ethanol therapy was used to achieve tumour coagulative necrosis. A 21-gauge PTC needle was placed into the tumour tissue adjacent to the vulnerable areas with US guidance. Dehydrated, sterile 99.5% ethanol was injected into tumours very slowly (1 mL/min) at the mean time of microwave emission to enlarge the coagulation zone. The quantity of ethanol was determined by the size and location of the tumour. For larger tumours that did not receive sufficient ablation, a higher amount of ethanol was necessary. The volume of unablated tumour was calculated by the width and length between the margins of ablation. Based on the area of unablated tumour during the treatment, the actual amount of ethanol was adjusted during operation. We avoided injecting ethanol into vessels or the biliary ducts during diffusion. While withdrawing the antenna, the needle track was coagulated to prevent tumour cell seeding and bleeding [Citation10].

Curative effect evaluation and follow up

Imaging was administered the day after MWA. The treatment effect was evaluated through CEUS or CE-MRI 48 to 72 h after ablation. If the enhanced imaging showed incomplete necrosis of the target tumour, one more MWA was delivered. Complete ablation was defined as no reappearance found on enhanced images (CEUS,CE-CT or CE-MRI) of an area of enhancement within the ablation zone. Technique efficacy was defined as the target tumour having achieved complete ablation without enhancement in any areas of the mass on enhanced images (CEUS, CE-CT or CE-MRI) obtained at the 1 month follow-up after MWA. Enhanced images (CEUS, CE-CT or CE-MRI) were used to monitor local recurrence or hepatic metastasis in months 1, 3, 6, 9 and 12 after treatment and every 6 months for the next year. The follow-up period was calculated from the first MWA in the authors’ institution after hepatic recurrence of HCC had been confirmed. Local tumour progression (LTP) was recognised as the reappearance of an area of enhancement within the ablation zone or less than 2.0 cm from its borders which was considered to be the complete ablation zone [Citation11]. The first and second dose efficacy rates were calculated. The former was defined as the percentage of target tumours successfully eradicated following the initial procedure or a second session, while the latter was recognised as the tumours having undergone successful repeat ablation following identification of local tumour progression [Citation8]. Intrahepatic metastasis was defined as the appearance of enhanced nodules in other positions in the liver.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 18.0. The basic characteristic data was quantitative variables and shown as means ± standard deviation. The accumulative survival rates were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method.

Results

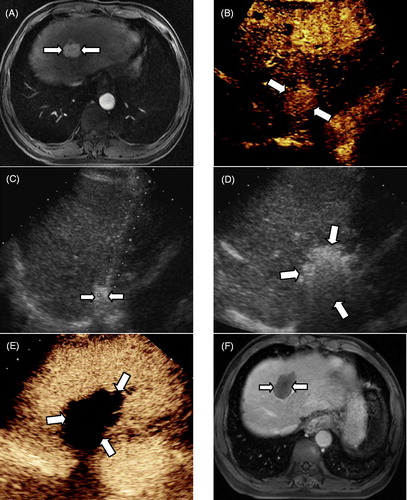

All 11 patients had confirmed intrahepatic recurrence of HCC after liver transplantation and accepted MWA treatment. Technique success was obtained in all cases. Among the 19 target lesions, 16 lesions achieved complete ablation for the first time, and three lesions needed two sessions. A thermal monitoring system was used in three tumours adjacent to the intestinal tract. An adjuvant small dose of ethanol therapy was needed in seven nodules, including three tumours adjacent to the diaphragm, two tumours adjacent to the gastrointestinal tract, one tumour adjacent to the inferior vena cava and one tumour near to the hepatic median vein (). The mean volume of ethanol injected was 4.68 ± 1.73 mL (range 2.5–7.8 mL). All the patients showed good tolerability to MWA treatment, and there were no serious complications such as intestinal thermal injury, liver abscess, hepatic failure, intratumoural bleeding or tumour seeding. Side effects were reported, including five fevers (45.4%) which ranged from 37° to 38.8 °C, three cases of nausea and vomiting (27.3%), five cases of local pain (45.4%), eight of increased blood transaminase levels (72.7%) which dropped to normal levels within 1–2 weeks. All of these side effects subsided with supportive and auxiliary treatment.

Figure 1. MWA in a 56-year-old man with intrahepatic recurrence of HCC adjacent to the diaphragm. (A) CE-MRI imaging obtained before ablation showed a hyper-enhanced area in segment II (long arrow). (B) The CEUS revealed a hyper-enhanced nodule in the left lobe. (C) Adjuvant 2.5 mL of ethanol was injected into the tumour edge adjacent to the diaphragm. (D) In the process of MWA, the hyper-echo completely covered the tumour. (E) CEUS obtained 3 days after ablation showed no enhancement (long arrow). (F) CE-MRI imaging obtained 4 months after ablation displayed no enhancement in the ablation zone (long arrow).

The follow-up period ranged from 5–33 months and all cases were followed up. Local tumour progression occurred in three cases (15.8%) at 1, 3 and 7 months after MWA; one was located below the right branch of the portal vein, one was adjacent to the liver median vein, and the other was near to the diaphragm. The patients with local tumour progression accepted repeat ablation. The MWA technique was found efficacious in all the tumours, and the first technique efficacy rate was 84.2% (16/19), while the second technique efficacy rate was 100%. Intrahepatic metastasis after MWA was observed in all 11 patients, and the interval varied from 1–13 months. For these 11 patients, three patients underwent transcatheter arterial chemoembolisation (TACE) treatment, five patients accepted MWA again and three patients did not accept any further treatment. By the end of August 2014 two patients were still alive; nine patients died of intrahepatic tumour progression and multiple distant metastases which resulted in organ failure. The 3, 6, 9, 12, 18 and 24 months accumulative survival rates were 90.9%, 81.8%, 71.6%, 51.5%, 30.7% and 15.3%, respectively (). The average survival time was 17.3 months (3.5–33).

Discussion

In theory, LT has the advantages of eradicating the tumours in the liver and removing liver cirrhosis, so primary liver cancer has been listed as a surgical indication for liver transplantation. However, not all liver cancers are suitable for LT, which has strict inclusion criteria. Mazzaferro [Citation12] proposed the Milan criteria, which are based on the tumour number, diameter, infiltration extent and distant metastasis. After clinical application of the Milan criteria, the 5-year survival rate after liver transplantation improved significantly. Then, on the basis of the Milan criteria, researchers carried out extensive follow-up studies on whether to expand LT standards, and have made remarkable achievements. Expanded criteria, such as the new Milan criteria [Citation13], the Pittsburgh criteria [Citation14] and the Hangzhou criteria in China [Citation15] have been proposed. But with the enlargement of the LT standard, tumour recurrence after LT has increased. The main reasons are the existence of micro metastases, the spread of tumour cells in the operation process, and the post-operative role of immunosuppressants in promoting tumour growth [Citation16]. Once the recurrence and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma has happened, very few treatment options are available for patients; most patients prescribed long-term use of immunosuppressants cannot tolerate surgery again [Citation4]. Post-operative chemotherapy has become widely used, and the international liver transplant registry data shows that 48% of liver cancer patients received adjuvant chemotherapy after LT [Citation17]. Doxorubicin is the most commonly used chemotherapy drug, but complete and partial response rates were about 4%, and the median progression-free survival was only 10 weeks. In recent years, targeted drugs, represented by sorafenib, has been used more frequently. According to the results of a case-control study performed by Sposito [Citation18], in a cohort of patients receiving sorafenib compared to that of patients receiving best supportive care, the median tumour progression time was 4.6 months, median survival time was 10.8 months.

MWA is a new method of minimally invasive treatment, with the advantages of good curative effect, no radiation and chemotherapy side effects and the greatest capacity to protect the body’s immune function. Theoretically, MWA can produce higher intratumoural temperatures, larger ablation zones, less ablation time and is less affected by the heat-sink effect [Citation19]. MWA has been widely used in treatment of malignant tumours. According to the study results and experience in our institution [Citation20,Citation21], for patients who cannot tolerate surgery again or patients with tumours adjacent to vulnerable tissues, MWA can offer more advantages without obvious complications. Severe abdominal cavity adhesion can often occur after transplantation, and it is difficult to separate and do surgery again. Local thermal ablation with percutaneous puncture can avoid reoperation, and can be performed repeatedly, protecting the residual liver function and achieving a similar effect to surgery again [Citation22].

In this study, all 19 tumours achieved technique efficacy, through one or two sessions. An adjuvant small dose of ethanol therapy was needed in seven nodules which were adjacent to the diaphragm, the gastrointestinal tract, the inferior vena cava or the hepatic median vein. If CEUS one or two days after first treatment showed residual tumour, a repeated ethanol injection with or without MWA was performed until complete necrosis of the tumour was confirmed. For the seven tumours which needed ethanol injection, five (71.4%) achieved complete necrosis. The aim of using ethanol was to kill the residual malignancy or pre-malignant foci which could be present but not necessarily visible adjacent to these vital tissues.

Local tumour progression occurred in three cases (15.8%), similar to the previous study in our department [Citation23]. Of the three nodules, one was near to the diaphragm, which was considered a relatively safe position. During the process of MWA, no assistive therapy such as ethanol injection, was applied to this nodule. The other two were adjacent to large vessels, one was located below the right branch of the portal vein, one was adjacent to the liver median vein, and thermal monitoring and ethanol injection were used. Residual tumour cells were the main cause of local tumour progression. Two types of enhanced imaging, including CEUS, CE-CT or CE-MRI, were performed to check whether any residual cancer still existed 48–72 h after the first procedure, and were used to decide whether a second session was needed to achieve complete ablation. However, enhanced imaging does not have the ability and resolution to show residual cancer cells. So, with the extension of time, residual cancer cells may increase and become visible tumour tissue despite the original tumour achieving complete necrosis having been confirmed by enhanced imaging.

According to the results of this study, the 3, 6, 9, 12, 18 and 24 months accumulative survival rates were 90.9%, 81.8%,71.6%,51.5%,30.7% and 15.3%, respectively. The median survival time was 17.3 months. It is known that recurrent HCC is associated with shorter survival, with death occurring 5.6 to 9 months after diagnosis, which is significantly shorter than the results of our study [Citation24]. At present, no consensus has been reached on the treatment of HCC recurrence after liver transplantation [Citation25,Citation26] and the efficacy of therapies are unsatisfactory. In theory, systemic chemotherapy was a good choice for patients with intrahepatic and extrahepatic recurrence. It was reported that the response rates of doxorubicin – the most widely used drug – had reached ∼10%. In another phase II trial, the PIAF protocol had produced a response rate of 20.8%, compared with doxorubicin alone (10.5%), but showed no significant difference in survival [Citation24]. As for the use of targeted therapy, preliminary data from a French case-control study showed less tolerance because of the skin and gastrointestinal side effects [Citation27]. Our preliminary study demonstrates that MWA could serve as a safe and effective topical treatment for recurrence of HCC after liver transplantation. Reports of thermal ablation in treating intrahepatic recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation are also limited. Ho [Citation28] reported a case of a patient with recurrent intrahepatic HCC after LT. He was accepted for radiofrequency ablation and has survived 24 months with normal level of a-fetoprotein and no macroscopic tumour on imaging. Gringeri et al. [Citation29] also reported a patient whose HCC tumour recurred 36 months after LT due to hepatitis C. He was successfully treated with laparoscopic MWA without any post-operative complications. The patient was disease free 24 months after MWA. Though their reports were only the result of one case, it may reflect that thermal ablation is a safe and effective treatment option for patients with recurrence of HCC after LT.

There were no major complications or severe side effects, which should mainly be attributed to the application of thermal monitoring and ethanol injection. A temperature measuring needle was inserted into the tumour marginal tissue, and the temperature was controlled between 45–60 °C, in which range thermal injury to the adjacent organ and structure can be prevented and the marginal field can be covered by the microwave thermal field [Citation9].The side effects were eased after treatment for symptomatic support, with almost no effect on patients’ life quality.

In addition, in some patients who underwent biliary intestinal anastomosis during the procedure of liver transplantation, the duodenum and periampullary natural barrier was damaged, and the risk of the intestinal bacteria retrograding into liver tissue increased [Citation30]. Coupled with long-term application of immunosuppressants, one must be alert to focal infection after ablation. For the five patients who accepted biliary intestinal anastomosis, lactulose was used for the preoperative intestinal preparation, and no liver abscess occurred after MWA.

This study had some limitations. First, the data were obtained from a single centre and the sample size was small. A multicentre study with a larger number of patients is required. Second, this study did not compare patients with intrahepatic recurrence of HCC who accepted or did not accept liver transplantation, so the baseline characteristic was unbalanced. Third, this study is a retrospective analysis; different approaches to follow-up might influence the evaluation of clinical outcomes.

Conclusion

MWA treatment is a safe and effective alternative for patients with intrahepatic recurrence of HCC after liver transplantation. It can inhibit tumour growth with fewer follow-up complications, mild side effects and good tolerability. However, due to the application of immune inhibitors and other factors, recurrence after liver transplantation was often accompanied by multiple intrahepatic recurrence and extrahepatic tumour metastasis. So the long-term effect of MWA treatment must be comprehensively evaluated.

Declaration of interest

This paper was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 81127006, 81430039), the National Key Technology Research and Development Programme of China (2013BAI01B01), the National Scientific Foundation Committee of China (grant numbers 81201167 & 30825010) and the Beijing Nova Program (XX2013108). The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:87–108

- Morise Z, Kawabe N, Tomishige H, Nagata H, Kawase J, Arakawa S, et al. Recent advances in the surgical treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:14381–92

- Jonas S, Bechstein WO, Steinmüller T, Herrmann M, Radke C, Berg T, et al. Vascular invasion and histopathologic grading determine outcome after liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis. Hepatology 2001;33:1080–6

- Rubin J, Ayoub N, Kaldas F, Saab S. Management of recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma in liver transplant recipients: A systematic review. Exp Clin Transplant 2012;10:531–43

- Zhou B, Shan H, Zhu KS, Jiang ZB, Guan SH, Meng XC, et al. Chemoembolization with lobaplatin mixed with iodized oil for unresectable recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after orthotopic liver transplantation. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2010;21:333–8

- Liang P, Wang Y. Microwave ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncology 2007;72:124–31

- Wang Y, Liang P, Yu X, Cheng Z, Yu J. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous microwave ablation of adrenal metastasis: Preliminary results. Int J Hyperthermia 2009;25:455–61

- Ahmed M, Solbiati L, Brace CL, Breen DJ, Callstrom MR, Charboneau JW, et al. Image-guided tumor ablation: Standardization of terminology and reporting criteria – a 10-year update. Radiology 2014;25:1691–705

- Liu S, Liang P, Yu X, Cheng Z, Han Z, Yu J. Percutaneous microwave ablation for liver tumours adjacent to the marginal angle. Int J Hyperthermia 2014;30:306–11

- Huang H, Liang P, Yu X, Cheng Z, Han Z, Yu J. Safety assessment and therapeutic efficacy of percutaneous microwave ablation therapy combined with percutaneous ethanol injection for hepatocellular carcinoma adjacent to the gallbladder. Int J Hyperthermia 2015;31:40–7

- Livraghi T, Meloni F, Di Stasi M, Rolle E, Solbiati L, Tinelli C, et al. Sustained complete response and complications rates after radiofrequency ablation of very early hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: Is resection still the treatment of choice? Hepatology 2008;47:82–9

- Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, Andreola S, Pulvirenti A, Bozzetti F, et al. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 1996;334:693–9

- Mazzaferro V, Llovet JM, Miceli R, Bhoori S, Schiavo M, Mariani L, et al. Predicting survival after liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma beyond the Milan criteria: A retrospective, exploratory analysis. Lancet Oncol 2009;10:35–43

- Marsh JW, Dvorchik I, Bonham CA, Iwatsuki S, et al. Is the pathologic TNM staging system for patients with hepatoma predictive of outcome. Cancer 2000;88:538–43

- Zheng SS, Xu X, Wu J, Chen J, Wang WL, Zhang M, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: Hangzhou experiences. Transplantation 2008;85:1726–32

- Regalia E, Coppa J, Pulvirenti A, Romito R, Schiavo M, Burgoa L, et al. Liver transplantation for small hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: Analysis of our experience. Trampl Proc 2001;33:1442

- Little SA, Fong Y. Hepatocellular carcinoma: Current surgical management. Semin Oncol 2001;28:474

- Sposito C, Mariani L, Germini A, Flores Reyes M, Bongini M, Grossi G, et al. Comparative efficacy of sorafenib versus best supportive care in recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation: A case-control study. J Hepatol 2013;59:59–66

- Wright AS, Sampson LA, Warner TF, Mahvi DM, Lee FT Jr. Radiofrequency versus microwave ablation in a hepatic porcine model. Radiology 2005;236:132–9

- Huang S, Yu J, Liang P, Yu X, Cheng Z, Han Z, et al. Percutaneous microwave ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma adjacent to large vessels: A long-term follow-up. Eur J Radiol 2014;83:552–8

- Liang P, Yang W, Yu X, Dong B. Malignant liver tumors: Treatment with percutaneous microwave ablation – complications among cohort of 1136 patients. Radiology 2009;251:933–40

- Chan AC, Poon RT, Cheung TT, Chok KS, Chan SC, Fan ST, et al. Survival analysis of re-resection versus radiofrequency ablation for intrahepatic recurrence after hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Surg 2012;36:151–6

- Liang P, Yu J, Yu X, Wang X, Wei Q, Yu S, et al. Percutaneous cooled-tip microwave ablation under ultrasound guidance for primary liver cancer: A multicentre analysis of 1363 treatment-naive lesions in 1007 patients in China. Gut 2012;61:1100–1

- Hollebecque A, Decaens T, Boleslawski E, Mathurin P, Duvoux C, Pruvot FR, et al. Natural history and therapeutic management of recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2009;33:361–9

- Clavien PA, Lesurtel M, Bossuyt PM, Gores GJ, Langer B, Perrier A, et al. Recommendations for liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: An international consensus conference report. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:e11–22

- Mancuso A, Mazzola A, Cabibbo G, Perricone G, Enea M, Galvano A, et al. Survival of patients treated with sorafenib for hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence after liver transplantation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Liver Dis 2015;47:324–30

- Dharancy S, Romano O, Lohro R, Pageaux GP, De Ledighen V, Hurtova M, et al. Tolerability of sorafenib in recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation: A case-control study. Liver Transpl 2008;14(S1):S216

- Ho CK, Chapman WC, Brown DB. Radiofrequency ablation of recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma in a patient after liver transplantation: Two-year follow-up. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2007;18:1451–3

- Gringeri E, Boetto R, Bassi D, D’Amico FE, Polacco M, Romano M, et al. Laparoscopic microwave thermal ablation for late recurrence of local hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplant: Case report. Prog Transplant 2014;24:142–5

- Wojcicki M, Milkiewicz P, Silva M. Biliary tract complications after liver transplantation: A review. Dig Surg 2008;25:245–57