Abstract

Purpose: The aim of this study was to retrospectively analyse the clinical data of 122 patients with caesarean scar pregnancy (CSP) treated in our hospital, to compare the outcomes between high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) and uterine artery embolisation (UAE). Materials and methods: Among the 122 patients, 76 patients were treated with HIFU followed by suction curettage under hysteroscopic guidance, 46 patients were treated with UAE followed by suction curettage under hysteroscopic guidance. Pain score, intraoperative blood loss in suction curettage under hysteroscopy guidance, time for vaginal bleeding, β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) to return to normal level, normal menstruation recovery, hospital stay, and the adverse effects were all compared. Results: No statistically significant differences between the two groups in the intraoperative blood loss, hospital stay, time for β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) to return to normal level, or time for normal menstruation recovery were observed. The pain score was lower and the adverse effects were fewer in the HIFU group than those in the UAE group. However, the time for vaginal bleeding was longer in the patients treated with HIFU than that of patients treated with UAE. Conclusions: Based on our results, it appears that either HIFU or UAE combined with suction curettage under hysteroscopic guidance is safe and effective in treating patients with CSP. Compared with UAE, HIFU treatment for CSP has the advantages of a lower pain score and fewer adverse effects.

Introduction

Caesarean scar pregnancy (CSP) was first described by Larsen and Solomon in 1978 [Citation1]. This is a rare condition and it is mainly presented with the implantation of a gestational sac, fertilised egg, or embryo within a previous caesarean section scar [Citation2]. Although CSP is rare, this condition may cause uterine rupture and catastrophic haemorrhage. In China, the caesarean delivery rate almost reached 50% and the prevalence of CSP is increasing [Citation3,Citation4]. Unfortunately, there is no consensus guideline for the management of CSP [Citation5]. Uterine artery embolisation (UAE), as a minimally invasive non-surgical treatment, was widely used to treat the uncontrollable excessive haemorrhage of CSP and to preserve the uterus and the patient’s future fertility. Previous studies have shown that a high success rate was achieved in the treatment of CSP using UAE. UAE followed by suction curettage appears to have more advantages and might be a priority option [Citation6–8]. However, the high complication rate of UAE is our concern, and severe adverse effects such as infertility, infection and ovarian dysfunction may occur after UAE [Citation9].

As a non-invasive treatment, ultrasound-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound (USgHIFU) has been widely applied in treating solid tumours [Citation10–12]. Over the last few years this non-invasive technique has also been used in the management of uterine fibroids and adenomyosis [Citation13–17]. Recently, USgHIFU has also been used in the management of CSP. Huang et al. treated four patients with CSP using HIFU combined with dilation and curettage [Citation18]. In another study, Xiao et al. treated 16 patients with CSP in 2–5 sessions of USgHIFU without any other supplemental treatments [Citation19]. In our previous study, 53 patients with CSP were successfully treated by HIFU followed by suction curettage under hysteroscopic guidance [Citation20]. All these results have shown that USgHIFU seems to be feasible and effective in treating patients with CSP. However, to the best of our knowledge, no study was performed to compare HIFU treatment with other therapeutic techniques in the management of CSP. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to compare efficacy and safety of HIFU followed by suction curettage under hysteroscopic guidance to UAE followed by suction curettage under hysteroscopic guidance.

Materials and methods

This study was approved by the ethics committee at our institution. Every patient signed an informed consent form before every procedure.

Patients

From January 2014 to December 2014, 122 patients with CSP were enrolled in our study.

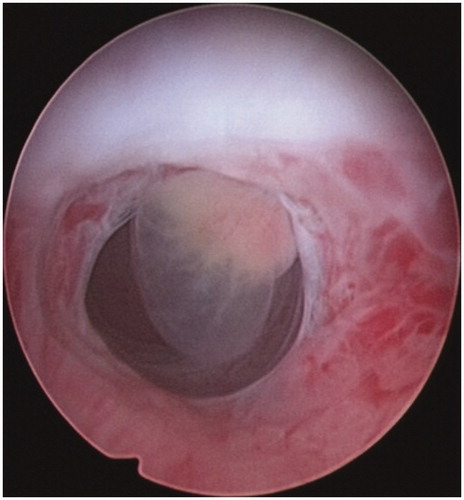

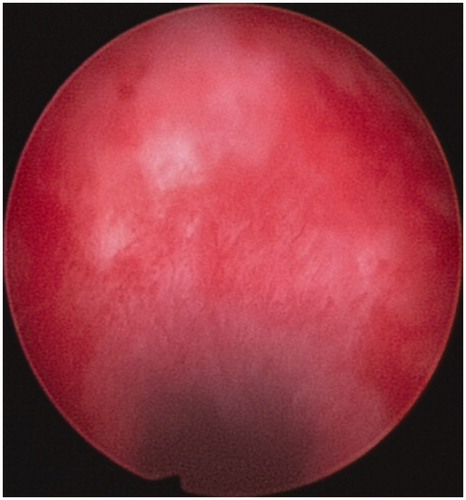

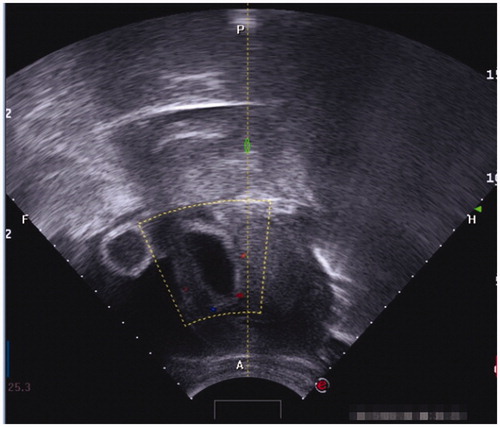

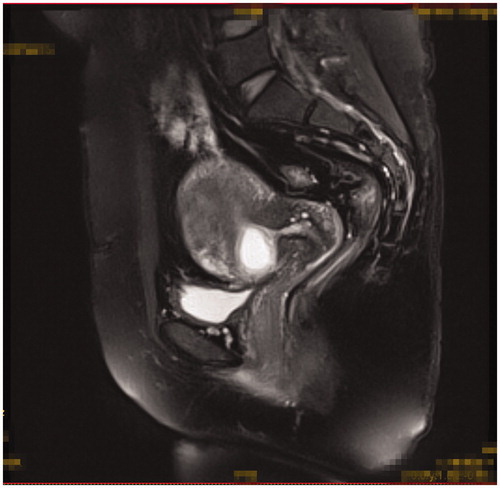

Inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) patients had a history of caesarean section delivery, 2) had amenorrhea and the urine pregnancy test was positive, 3) the diagnosis of CSP was confirmed by ultrasound () and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) () indicating a CSP based on the diagnostic criteria, recommended by Godin et al. [Citation21], 4) gestational age less than 13 weeks, 5) the availability of complete clinical data.

Figure 1. Gestational sac implanted in the previous caesarean scar with empty uterus cavity and cervical canal; no myometrium was visible between the bladder and the sac.

Figure 2. Gestational sac implanted in the previous caesarean scar with empty uterus cavity and cervical canal (sagittal view of the MRI).

Exclusion criteria: 1) patients with pelvic inflammatory diseases, 2) post-operative pathology indicating no trophoblastic disease, 3) had other treatment for other diseases unrelated to CSP.

After the diagnosis was made, two treatment options were offered to the patients. Out of 122 patients, 76 patients chose treatment with HIFU followed by suction curettage under hysteroscopic guidance, 46 patients chose treatment with UAE followed by suction curettage under hysteroscopic guidance.

Ultrasound-guided HIFU ablation

The procedure of ultrasound-guided HIFU, as described in our previous publication [Citation20], was performed with the JC-200 focused ultrasound tumour therapeutic system (Chongqing Haifu Medical Tech, Chongqing, China). The therapeutic energy was produced by a transducer with a 20 cm diameter and a focal length of 15 cm. An ultrasound imaging probe (My-Lab70, Esaote, Italy) is situated at the centre of the transducer and allows real time sonographic monitoring during HIFU treatment. The transducer is located in a water tank filled with degassed water and its movement is controlled by a computer.

All patients were asked to have bowel preparations for 3 days before HIFU treatment. Every patient was requested to have specific skin preparation: to shave and degrease her anterior abdominal wall from the umbilicus to the level of upper margin of the pubic symphysis. A urinary catheter was then inserted to control the bladder volume.

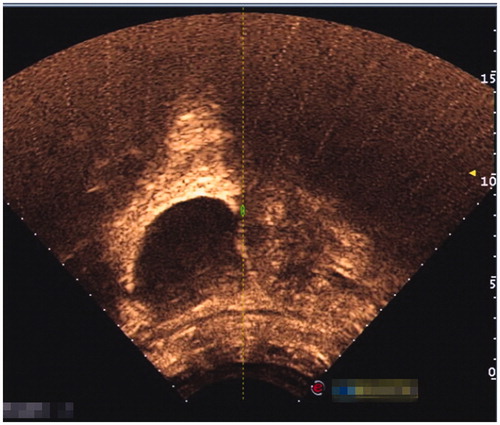

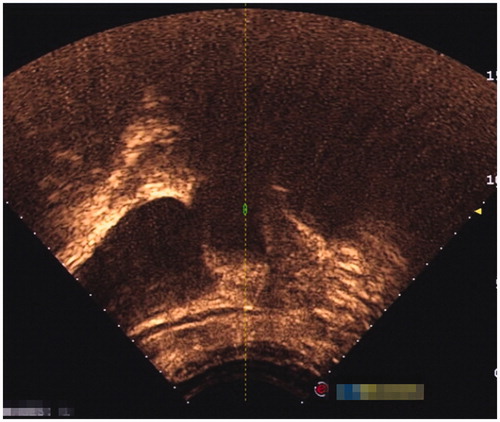

The HIFU procedure has also been described in the previous study [Citation20]. Briefly, the procedure was performed under conscious sedation. Every patient was positioned prone on the HIFU table with the anterior abdominal wall in contact with degassed water over the transducer in a sealed tank. The sagittal view of ultrasound scanning mode was selected, and the treatment plan was made by dividing the gestational sac into different slices with a thickness of 3 mm. The acoustic output power of 350–400 W was used. HIFU sonication terminated when the signal of the pregnancy tissue blood flow disappeared or a grey scale change at the target tissue was observed on the colour Doppler ultrasound. Contrast enhanced ultrasound (SonoVue, Bracco, Italy) was used to check the blood perfusion in the pregnancy tissue. Suction curettage under hysteroscopic guidance was performed at an average of 2.8 (range 1–5) days after HIFU ablation.

Uterine artery embolisation

UAE was performed under local anaesthesia. A right trans-femoral approach was used for artery access, and super-relective embolisation of both uterine arteries was performed using gelatin sponge powder by an experienced radiologist. Catheterisation via the femoral artery and flush arteriography was performed before selective embolisation. Post-embolisation angiography was performed to confirm that the occlusion of the vessels was complete. After an average of 3.3 days (range 1–6), patients received suction curettage under hysteroscopic guidance [Citation7].

Suction curettage under hysteroscopic guidance

Suction curettage under hysteroscopic guidance was performed under general anaesthesia. The patients were placed in a dorsal lithotomy position. The uterine cavity and the location of the pregnancy tissue were visualised using a 30° diagnostic hysteroscope. Normal saline was used as a distension medium. During the procedure, the vacuum pressure was set at 0.04 MPa. The operator gently inserted a 7-or 8-mm suction cannula into the uterine cavity and moved the cannula back and forth, rolling the cannula gently to remove the pregnancy tissues from the previous caesarean scar. Then, the hysteroscope was reinserted again to detect any retained pregnancy tissues from previous caesarean scars ( and ). If necessary, semi-flexible forceps or a wire-loop electrode could be used to remove the retained pregnancy tissues. If required, electrocoagulation was used to stop bleeding from the wound surface. Balloon catheterisation of the cervical canal by a 30-mL Foley catheter or a diluted 10–20-mL vasopressin solution (0.24 U/mL, 12 units diluted into 50 mL normal saline) injection in equal amounts into the cervical stroma at the 4 and 8 o’clock positions to tamponade post-procedural bleeding were performed if required.

Follow-up observation

Following the approved protocol, serum β-hCG was checked weekly until it returned to its normal level. All the patients were requested to return to our department for a colour Doppler ultrasound examination 1 month after suction curettage. The time of vaginal bleeding, the first return of the menstrual cycle, and the number of adverse effects were all recorded.

Statistical methods

SPSS 17.0 software (IBM, New York) was used for statistical analysis. All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median. The t-test, χ2 test, and rank sum test were used for the analysis of these data. A value of P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The average age of the patients was 32.1 ± 5.1 years old (range 22–46). Among the 122 patients, 91 (74.6%) had had one low-segment caesarean delivery, 29 (23.8%) had had two low-segment caesarean deliveries, and two (1.6%) patients had had three low-segment caesarean deliveries. In these patients, 112 (91.8%) were diagnosed with CSP for the first time, 8 (6.6%) were diagnosed with CSP for the second time, and 2 (1.6%) patients were diagnosed with CSP for the third time. The median interval from the last caesarean section to CSP was 48 months (range 4–240 months). The average gestational age was 57.3 ± 16.5 days (range 37–91 days). The median serum β-hCG level before treatment was 26,006 mIU/mL (range 31.7–205936 mIU/mL), the average largest diameter of the sac/mass was 35.3 ± 16.9 mm (range 10–100 mm). No statistically significant differences in age, gestational age, largest diameter of the sac/mass, serum β-hCG level before treatment, gravidity, parity, number of caesarean deliveries, or interval from the last caesarean section were observed between the two groups of patients (P > 0.05) (see ).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the patients with CSP.

HIFU ablation and UAE evaluation

All the patients in the HIFU group received only one session of HIFU treatment. The median treatment time (defined as from the first sonication to the last sonication) was 67.5 (range 13–160) min. The median HIFU sonication time was 590 (range 100–2150) s. Before HIFU ablation, the colour Doppler showed fetal cardiac activity in 23 cases. After HIFU treatment, the fetal cardiac activity disappeared. Contrast enhanced ultrasound showed no perfusion in the pregnancy tissue immediately after the HIFU treatment ( and ). During HIFU treatment, the main complaints were sacral pain and/or lower abdominal pain. The pain subsided within 24 h without any therapy. All the 46 patients in the UAE group received one session of UAE and post embolisation angiography confirmed that the embolisation of uterine artery was successful. After UAE, the patients mainly complained of lower abdominal pain. The average pain scores were 2.9 ± 1.0 in the HIFU group and 4.4 ± 1.6 in the UAE group (). The pain score in the UAE group was significantly higher than that of the HIFU group (P < 0.001).

Evaluation of suction curettage under hysteroscopic guidance

All 122 patients received suction curettage under hysteroscopic guidance after HIFU or UAE. The median volume of intraoperative blood loss was 20 mL (range 10–800 mL). No statistically significant difference in the depth of the uterus, or intraoperative blood loss between the two groups was observed (P > 0.05) ().

Table 2. Comparison of clinical outcomes between the two groups.

Table 3. Comparison of the adverse effects between the groups.

In the HIFU group, uterus perforation occurred in one patient (1.3%) during the suction curettage procedure. In addition, subcutaneous induration was seen in one patient (1.3%), and we observed vaginal bleeding of more than 500 mL during the suction curettage and hysteroscopy procedure in four patients (5.2%).

While in the UAE group high fever was seen in one patient (2.2%), acute pelvic inflammation occurred in one patient (2.2%), mild lower limb pain or numbness was observed in six patients (13.0%), mild left hip pain was encountered in one patient(2.2%), and vaginal bleeding of more than 500 mL was observed in one patient (2.2%).

There was no statistically significant difference in fever, acute pelvic inflammation, uterus perforation, subcutaneous induration, vaginal bleeding, hip pain or readmitted patients between the two groups (P > 0.05). The HIFU group had fewer adverse effects of lower limb pain or numbness than the UAE group (P < 0.05) ().

Follow-up result

showed that the average duration of hospital stays was 7.8 ± 1.7 (range 5–15) days in the HIFU group, while it was 7.9 ± 3.0 (range 4–21) days in the UAE group. All the patients reported slight vaginal bleeding after suction curettage. The average duration of vaginal bleeding was 15.5 ± 9.8 (range 1–40) days in the HIFU group, while it was 11.7 ± 10.0 (range 2–60) days in the UAE group. The average time of menstruation recovery was 34.9 ± 10.6 (range 10–60) days in the HIFU group, while it was 31.7 ± 10.8 (range 11–70) days in the UAE group. The time for the serum β-hCG level to return to normal was 27.6 ± 8.4 (range 7–48) days in the HIFU group, while it was 27.8 ± 7.7 in the UAE group. No statistically significant difference in hospital stay, the average time of menstruation recovery, or the time taken for the serum β-hCG level to return to normal was observed between the two groups (P > 0.05). However, in the HIFU group the duration of vaginal bleeding was slightly longer than UAE group (P < 0.05) (). During the follow-up period, no catastrophic haemorrhage was observed and no further UAE or hysterectomy was performed.

Discussion

The treatment purpose of CSP is not only to decrease the risk of uterine rupture and catastrophic haemorrhage, but also to preserve the uterus to maintain further fertility [Citation5]. However, there was no universal guideline on the management of CSP [Citation22,Citation23]. HIFU has been used in the treatment of CSP as a non-invasive treatment. Since the small blood vessels could be destroyed by HIFU [Citation24], HIFU may decrease the risk of haemorrhage during the procedure of suction curettage under hysteroscopic guidance by destroying small blood vessels with a diameter smaller than 2 mm around the CSP. Three previous studies [Citation18–20] using HIFU combined with or without suction curettage to treat CSP patients in three different medical centres have revealed that HIFU is a safe and effective treatment for CSP. However, lack of comparison with other treatments was the limitation of all these three studies.

In this current study, the results showed no statistically significant differences in the depth of the uteri, intraoperative blood loss, hospital stay, the average time of menstruation recovery, and the time taken for the serum β-hCG level to return to normal between the patients treated with HIFU followed by suction curettage and the patients treated with UAE in combination with suction curettage. Therefore, the results demonstrated that HIFU followed by suction curettage is as effective as UAE in combination with suction curettage.

The safety of the treatment for CSP is a main concern. In this study, we found both HIFU and UAE are safe in the treatment of CSP patients. During and immediately after HIFU treatment the common adverse effects were sacral pain, and/or lower abdominal pain. The pain in most of the patients subsided within 3 days without any treatment. The adverse effects of UAE in this study included high fever, acute pelvic inflammation, mild lower limb pain or numbness, mild left hip pain, and excessive vaginal bleeding. In comparison with UAE, the pain score of the lower abdominal pain after HIFU was significantly lower. The reason can be explained by ‘post embolisation syndrome’ which can occur after UAE. Since the uterine artery was embolised and the uterine blood supply decreased dramatically, uterine contraction occurred and caused severe pain. In this study we found that the rate of lower limb pain or numbness was significantly higher in the patients treated with UAE than that of patients treated with HIFU. Therefore, it seems that HIFU had fewer adverse and more minor effects.

During the procedure of suction curettage under hysteroscopic guidance, uterine perforation at previous caesarean scars occurred in one patient treated with HIFU. We have reviewed this case carefully and found that the myometrium between the gestational sac and the bladder was very thin. The procedure of suction curettage under hysteroscopic guidance should be performed more carefully for those patients with thin layers of the intervening myometrium between the gestational sac and the bladder. Furthermore, we observed four patients in the HIFU group and one patient in the UAE group with excessive vaginal bleeding during suction curettage. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups. We further reviewed these patients and found that two in the HIFU group had CSP lesions 54 mm and 60 mm in the largest diameter, which were larger than the other cases. However, the sonication time in these two patients was only 700 s. On the other hand, two other patients in the HIFU group and one in the UAE group had CSP lesions deeply implanted into the caesarean scar. This adverse effect may be decreased through increasing the sonication time to deliver more energy to heat the target tissue, or using methotrexate (MTX) before HIFU to decrease the activity of the chorionic villi. Wang et al. reported their results of 128 patients with CSP treated with dilation and curettage after UAE and found that a CSP mass diameter of 6 cm or more was the only significant risk factor for excessive bleeding [Citation25]. Therefore, for these patients with large and/or deeply implanted CSP lesions, the suction curettage under hysteroscopic guidance does not seem to be the most appropriate method.

In this study one patient after UAE had mild but persistent left hip pain for one month, and seven patients complained of mild lower limb pain or numbness. All of them recovered in 3–6 months without any special treatment. These adverse effects may be caused by misembolisation from microspheres or polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) particles flowing or drifting into the superior gluteal artery, or the blood supply of the sciatic nerve and the obturator nerve. We also observed one patient who had a high fever after the UAE, and another patient who had acute pelvic inflammation with a high fever and abdominal pain after the suction curettage. Both of them had experienced a long period of vaginal bleeding before they were admitted to hospital. This history may have increased the risk of infection. Therefore, careful examination is needed to exclude infection before UAE. Administration of preventive antibiotics before and after the procedure may help to decrease the risk. Both of these patients were treated by antibiotics for more than one week and the infection was controlled. Other UAE-related complications were not observed in this study.

This study is limited because it was a retrospective observational study. Although the basic characteristics in the two groups had no significant differences, some unexpected factors may have affected the results. Future prospective, randomised multi centre studies are needed. A previous study [Citation19] has shown that it is not necessary to perform suction curettage to remove the CSP tissue after HIFU ablation; their sample size was too small. Therefore, future studies to compare HIFU followed by suction curettage with HIFU without suction curettage are also needed. Although HIFU could be used safely to terminate CSP, it still carries the risk of excessive vaginal bleeding during the suction curettage and hysterscopic procedure. Many studies have shown that MTX could kill CSP fetal tissue. Thus, injection of MTX before HIFU ablation may decrease the activity of the chorionic villi, which could result in easier necrosis of CSP. Future studies combining MTX with HIFU are also needed. For those large and/or deeply implanted CSP, further studies comparing HIFU with laparoscopic resection are needed.

Conclusion

Based on our results, it appears that both HIFU and UAE combined with suction curettage under hysteroscopic guidance are safe and effective in treating patients with CSP. Compared with UAE, HIFU treatment for CSP has the advantages of lower pain levels and fewer adverse effects. It may be a promising alternative treatment.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Larsen JV, Solomon MH. Pregnancy in uterine scar sacculus: An unusual cause of postabortal hemorrhage. S Afr Med J 1978;53:142–3

- Ash A, Smith A, Maxwell D. Caesarean scar pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2007;114:253–63

- Zhang J, Liu Y, Meikle S, Zheng J, Sun W, Li Z. Cesarean delivery on maternal request in southeast China. Obstet Gynecol 2008;111:1077–82

- Wang CB, Tseng CJ. Primary evacuation therapy for cesarean scar pregnancy: Three new cases and review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2006;27:222–6

- Litwicka K, Greco E. Caesarean scar pregnancy: A review of management options. Curr Opin Obstet Gyn 2013;25:456–61

- Zhang B, Jiang ZB, Huang MS, Guan SH, Zhu KS, Qian JS, et al. Uterine artery embolization combined with methotrexate in the treatment of cesarean scar pregnancy: Results of a case series and review of the literature. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2012;23:1582–8

- Zhuang Y, Huang L. Uterine artery embolization compared with methotrexate for the management of pregnancy implanted within a cesarean scar. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;201:e1–3

- Li C, Li C, Feng D, Jia C, Liu B, Zhan X. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization versus systemic methotrexate for the management of caesarean scar pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2011;113:178–82

- Hois EL, Hibbeln JF, Alonzo MJ, Chen ME, Freimanis MG. Ectopic pregnancy in a cesarean section scar treated with intramuscular methotrexate and bilateral uterine artery embolization. J Clin Ultrasound 2008;36:123–7

- Xie B, Zhang C, Xiong C, He J, Huang G, Zhang L. High intensity focused ultrasound ablation for submucosal fibroids: A comparison between type I and type II. Int J Hyperthermia 2015;31:593–9

- Orsi F, Arnone P, Chen W, Zhang L. High intensity focused ultrasound ablation: A new therapeutic option for solid tumors. J Cancer Res Ther 2010;6:414–20

- Rodrigues DB, Stauffer PR, Vrba D, Hurwitz MD. Focused ultrasound for treatment of bone tumours. Int J Hyperthermia 2015;31:260–71

- Xiong Y, Yue Y, Shui L, Orsi F, He J, Zhang L. Ultrasound-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound (USgHIFU) ablation for the treatment of patients with adenomyosis and prior abdominal surgical scars: A retrospective study. Int J Hyperthermia 2015;31:777–83

- Zhang X, Li K, Xie B, He M, He J, Zhang L. Effective ablation therapy of adenomyosis with ultrasound-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2014;124:207–11

- Orsi F, Monfardini L, Bonomo G, Krokidis M, Della Vigna P, Disalvatore D. Ultrasound guided high intensity focused ultrasound (USgHIFU) ablation for uterine fibroids: Do we need the microbubbles? Int J Hyperthermia 2015;31:233–9

- Zhang L, Zhang W, Orsi F, Chen W, Wang Z. Ultrasound-guided high intensity focused ultrasound for the treatment of gynaecological diseases: A review of safety and efficacy. Int J Hyperthermia 2015;31:280–4

- Zhou M, Chen JY, Tang LD, Chen WZ, Wang ZB. Ultrasound-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound ablation for adenomyosis: The clinical experience of a single center. Fertil Steril 2011;95:900–5

- Huang L, Du Y, Zhao C. High-intensity focused ultrasound combined with dilatation and curettage for cesarean scar pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2014;43:98–101

- Xiao J, Zhang S, Wang F, Wang Y, Shi Z, Zhou X, et al. Cesarean scar pregnancy: Noninvasive and effective treatment with high-intensity focused ultrasound. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014;211:356. e1–7

- Zhu X, Deng X, Wan Y, Xiao S, Huang J, Zhang L, et al. High-intensity focused ultrasound combined with suction curettage for the treatment of cesarean scar pregnancy. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e854

- Godin PA, Bassil S, Donnez J. An ectopic pregnancy developing in a previous caesarian section scar. Fertil Steril 1997;67:398–400

- Xin W, Xiaohong X, Xuezhe W, Ru L, Ying Y, Qing W, et al. Combined laparoscopy and hysteroscopy vs. uterine curettage in the uterine artery embolization-based management of cesarean scar pregnancy: A cohort study; Int J Clin Exp Med 2014;7:2793–803

- Wang G, Liu X, Bi F, Yin L, Sa R, Wang D, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy of laparoscopic resection for the management of exogenous cesarean scar pregnancy. Fertil Steril 2014;101:1501–7

- Wu F, Chen WZ, Bai J, Zou JZ, Wang ZL, Zhu H, et al. Tumor vessel destruction resulting from high-intensity focused ultrasound in patients with solid malignancies. Ultrasound Med Biol 2002;28:535–42

- Wang JH, Qian ZD, Zhuang YL, Du YJ, Zhu LH, Huang LL. Risk factors for intraoperative hemorrhage at evacuation of a cesarean scar pregnancy following uterine artery embolization. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2013;123:240–3