Abstract

Purpose: The aim of this study was to assess the capacity of two methods of surgical pancreatic stump closure in terms of reducing the risk of pancreatic fistula formation (POPF): radiofrequency-induced heating versus mechanical stapler. Materials and methods: Sixteen pigs underwent a laparoscopic transection of the neck of the pancreas. Pancreatic anastomosis was always avoided in order to work with an experimental model prone to POPF. Pancreatic stump closure was conducted either by stapler (ST group, n = 8) or radiofrequency energy (RF group, n = 8). Both groups were compared for incidence of POPF and histopathological alterations of the pancreatic remnant. Results: Six animals (75%) in the ST group and one (14%) in the RF group were diagnosed with POPF (p = 0.019). One animal in the RF group and three animals in the ST group had a pseudocyst in close contact with both pancreas stumps. On day 30 post-operation (PO), almost complete atrophy of the exocrine distal pancreas was observed when the main pancreatic duct was efficiently sealed. Conclusions: Our findings suggest that RF-induced heating is more effective at closing the pancreatic stump than mechanical stapler and leads to the complete atrophy of the distal remnant pancreas.

Introduction

Pancreatic resections are among the most technically complex operations conducted by surgeons. One of the gravest complications after pancreatic resection is the development of a post-operative pancreatic fistula (POPF), which involves leakage of the digestive pancreatic enzymes from the pancreatic ductal system via an anomalous connection into the peri-pancreatic space or the peritoneal cavity [Citation1]. POPF is largely the most significant cause of morbidity and mortality after pancreatectomy, and may lead to haemorrhage, sepsis, and subsequent death due to leakage from pancreatic anastomoses [Citation2].

Distal pancreatectomy (DP) is frequently aimed at removing a tumour in the body or tail of the pancreas. After removal of the pancreatic fragment, the stump must be managed to prevent leakage from this area. Several methods have been proposed to seal the pancreatic ducts at the transection plane, such as suturing or by means of mechanical stapler. A recent clinical study showed no difference in POPF incidence between hand-sewn versus mechanical stapler [Citation3], which was as high as 36% in both groups. Accordingly, innovative surgical techniques need to be identified to reduce this adverse outcome.

In this context, radiofrequency (RF) energy has been used both experimentally and clinically to manage the pancreatic remnant after DP due to its ability to seal the main and secondary pancreatic ducts [Citation4,Citation5].

This rationale has been tested in a recent RCT (NCT01051856) performed at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN, in which a RF-assisted device (Tissuelink®, TissueLink Medical, Dover, NH, USA) was compared to stapling with a bioabsorbable staple-line reinforcement (Seamguard®, Gore Medical, Flagstaff, AZ, USA). Unfortunately this study was closed early because of poor accrual in 2014. Recent studies using a porcine pancreatic model suggested that distal pancreatic transection by such RF devices can seal the main pancreatic duct easily and safely [Citation6,Citation7]. However, it is still necessary to clarify the potential of RF-induced heating for managing the pancreatic stump. Unfortunately, with conventional experimental models involving transection of the distal zone, the incidence of POPF is usually under 10% [Citation4,Citation6,Citation7], which either hampers the final demonstration of the superiority of any method or requires an enormous sample size. In order to make the differences between the methods as clear as possible, we recently proposed a new experimental model prone to pancreatic fistula formation, based on transecting the proximal (neck of the pancreas) instead of the distal zone, and avoiding performing pancreatic anastomosis [Citation8]. This surgical approach is rarely performed in current clinical practice, mainly because it entails the excessive incidence of a long-lasting fistula (up to 94% for an average of 73 days [Citation9]). In spite of this drawback, these fistulas are usually well tolerated and cause no mortality, which suggests that the experimental model is feasible. The objective of the present study was to use this new experimental model to clarify whether RF-induced heating on the neck of the pancreas would be more effective than a mechanical suture in terms of minimising the risk of POPF.

Material and methods

Experimental model

Sixteen Landrace pigs with a mean preoperative weight of 37 kg (range 23–47 kg) obtained from the farm of the Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona (Spain) underwent laparoscopic DP, in which pancreatic stump closure was conducted either by stapler (ST group, n = 8) or radiofrequency energy (RF group, n = 8). The animal research protocol was approved by the Ethical Commission of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (authorisation number CEEAH 1256). In the RF group, an internally cooled electrode (3-mm diameter) was used to coagulate and seal the tissue on the transection plane (Coolinside device, Apeiron Medical, Valencia, Spain). The electrode was connected to a 200-W RF generator model CC-1 (Radionics, Burlington, MA, USA). Once thermally coagulated, mechanical cutting was performed by the distally incorporated blade on the RF electrode (). In the ST group, closure was performed by the Endo GIA® 60-mm mechanical device (Covidien, Norwalk, CT) with 3.5-mm staples, similarly to previous experimental and clinical studies [Citation7,Citation11]. No pancreatic anastomosis was performed on any animal. Preoperative care and anaesthesia were provided by fully trained veterinary staff. All the surgical procedures were performed by the same surgical team (D.D. and L.H.) using a four-port laparoscopic approach. In all animals, a dissection of the neck of the pancreas over the portal vein was performed using conventional endoscopic scissors and graspers. According to a previous study on pancreas anatomy [Citation12] the main pancreatic duct running along the body and tail of the pancreas in the pig coalesces with a common main pancreatic duct in the head by two ducts: one anterior to the portal vein and another posterior. This means that in order to achieve complete obstruction of the distal part (body and tail) of the pancreas both ducts must be severed (). The main pancreatic duct was neither identified nor sutured after transection in either group. A Blake Silicon Drain (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ) was positioned adjacent to the pancreatic stump and extracted from the animal’s abdomen through the 5-mm inferior right trocar orifice. The proximal end was subcutaneously tunnelled to the animal’s back and connected to a reservoir. All wounds were closed in standard fashion.

Figure 1. Normal anatomy of the porcine pancreas and the surgical procedure after the first section of the pancreas according to Ferrer et al. [Citation12]. The ‘splenic’ lobe (SL), corresponding to the tail and body in the human pancreas, is attached to the spleen. The ‘duodenal’ lobe (DL), corresponding to the head of the pancreas, is located adjacent to the duodenum while the ‘connecting’ lobe (CL), corresponding to the uncinated process is an extension of the pancreas which is anterior to the portal vein (PV). There is also a ‘bridge’ (B) of pancreatic tissue serving as an anatomical connection between the splenic and connecting lobes behind the portal vein. In order to achieve a complete separation of the distal part (body and tail) two transection planes were performed (numbers 1 and 2) with the transection device (TD) (either RF electrode or mechanical stapler).

![Figure 1. Normal anatomy of the porcine pancreas and the surgical procedure after the first section of the pancreas according to Ferrer et al. [Citation12]. The ‘splenic’ lobe (SL), corresponding to the tail and body in the human pancreas, is attached to the spleen. The ‘duodenal’ lobe (DL), corresponding to the head of the pancreas, is located adjacent to the duodenum while the ‘connecting’ lobe (CL), corresponding to the uncinated process is an extension of the pancreas which is anterior to the portal vein (PV). There is also a ‘bridge’ (B) of pancreatic tissue serving as an anatomical connection between the splenic and connecting lobes behind the portal vein. In order to achieve a complete separation of the distal part (body and tail) two transection planes were performed (numbers 1 and 2) with the transection device (TD) (either RF electrode or mechanical stapler).](/cms/asset/0158d953-28b9-49eb-8cab-efa116aa2b13/ihyt_a_1136845_f0001_c.jpg)

The animals were allowed to awaken from anaesthesia and were extubated when clinically indicated. All animals were given water ad libitum for the first 24 h and subsequently fed twice daily with pig chow thereafter. Antibiotics (amoxicillin 20 mg kg−1 IM, q24 h) were administered for the first 3 days PO. All animals were inspected twice a day for the first 7 days PO to detect any clinical signs of pancreatic leak or sepsis and to monitor abdominal drains. All animals received buprenorphine (0.02–0.03 mg kg−1 IM, q128 h) for the first 24 h PO and meloxicam (0.12 mg kg−1 IM, q24 h) for post-operative analgesia in the first 5 days PO. All animals received 100 µg h−1 fentanyl patch after surgical procedure. The patch was maintained during the first 3 days PO.

Analysed variables

Peripheral blood was collected for measurement of serum amylase and glucose levels prior to the surgical procedure, 3 h after intervention, on PO days 1, 3 and 7 and 4 weeks PO, just before euthanasia. The blood samples were then centrifuged at 2500 g for 10 min to extract the serum. Peripancreatic fluid amylase was measured from the drain tube on days 1, 3 and 7 PO and, if present, during laparotomy 4 weeks PO. The surgical drain was removed beyond day 7 PO if no evidence of pancreatic leak was observed (see definition of POPF in below) and if the output was <20 mL per day.

Four weeks after pancreatic transection, all animals were again anaesthetised, intubated, and ventilated as described above. Exploratory laparotomy was performed and the peritoneal cavity was assessed for excessive adhesions, free peritoneal fluid, or any undrained collection/abscess. The pancreatic stumps were identified, skeletonised, and photographed. The pancreas (head, uncinated process and distal pancreas) was dissected, removed, and temporarily placed in 10% buffered neutral formalin.

The main pancreatic duct was identified and cannulated with an angiocatheter both through the ampulla in the duodenum and after cutting the pancreatic tail. A 1:5 dilution of black China dye was then injected into the pancreatic duct in a retrograde fashion to assess for macroscopic dye extravasation from the pancreatic stump. Thereafter, the specimen was immersed in 10% buffered neutral formalin for further histopathological processing. The animals were then sacrificed with a commercial euthanasia solution.

The primary outcome was the development of POPF which was defined following the International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) guidelines [Citation13], i.e. as 1) macroscopic leak (evidence of dye extravasation from the pancreatic stump when catheterising the distal main pancreatic duct), 2) any undrained amylase-rich fluid collections/abscess, or 3) greater than threefold drain/serum amylase ratio after day 3 PO.

We also analysed the following outcomes: operative time, transection time, intraoperative complications, weight variations (crude or relative to preoperative values), post-operative serum amylase/glucose and peritoneal fluid amylase, histopathological alterations of the pancreatic remnant, wound infection, and other post-operative clinical parameters (anorexia, emesis, lethargy, and narcotic need).

Histopathological study

Consecutive sections of 5 mm thickness were taken from each animal from the margin of the pancreatic transection, in both proximal and distal samples. Alternative sections were routinely processed, paraffin-embedded, cut to a thickness of 3 µm, stained with haematoxylin and eosin, and evaluated by a pathologist blinded to the experimental design. The pathologist graded the severity of the exocrine pancreas atrophy using a score ranging from 0 to 5, which was chosen to maximise detection and repeatability [Citation14].

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as median and minimum–maximum value. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to determine the variables’ distribution. The Student’s t test was used to make pair-wise comparisons of normal distributed parameters, and the Mann-Whitney U test was used for non-parametric data. Dichotomous variables were compared using the chi-square test. Additionally, laboratory analyses that included repeated measures were evaluated by two-way analysis of variance [Citation15] with the Bonferroni test for post hoc analysis. Data collection and analyses were performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 19.0, IBM, Armonk, NY).

Results

Operative findings and post-operative follow-up

shows the intra- and post-operative variables of each experimental group. There were no intraoperative deaths or major complications during surgery. No significant differences were found either in operative time or transection time between the groups. One animal died in each group during the post-operative period. The remaining animals were euthanised on day 30 PO in good clinical condition with a mean weight gain of 20.5 kg (range 8.5–30.0 kg). Only the death in the ST group (animal 4) was related to a pancreatic leak (see below). shows detailed information on the clinical progress of each animal studied. Animal 14 in the RF group died on day 3 PO after an uneventful immediate post-operative period. At necropsy, a bowel volvulus by torsion of the mesentery leading to gangrene of half the bowel was observed. No other findings were encountered at necropsy.

Table 1. Intra- and post-operative variables of each experimental group.

Table 2. Detailed information on the clinical progress of the animals studied.

Findings at necropsy and incidence of post-operative pancreatic fistula

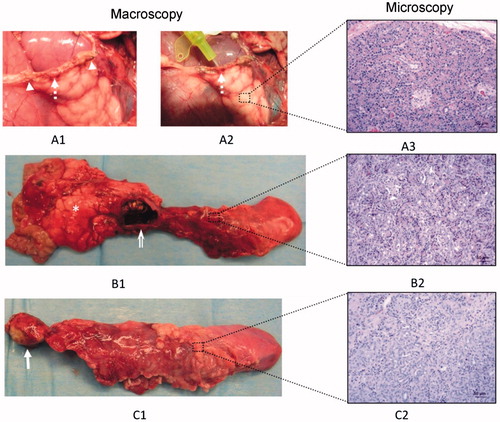

shows a schematic with the main findings, and shows macroscopic and microscopic pictures of some of these findings. In all cases, no macroscopic changes were observed in the proximal pancreas, with complete microscopic preservation of the pancreatic architecture. All the animals in the RF group had four round-shaped areas of coagulation necrosis completely surrounded by a dense layer of mature connective tissue, which corresponded to the RF-induced thermal coagulation on both transection planes. This feature was not found in the ST group.

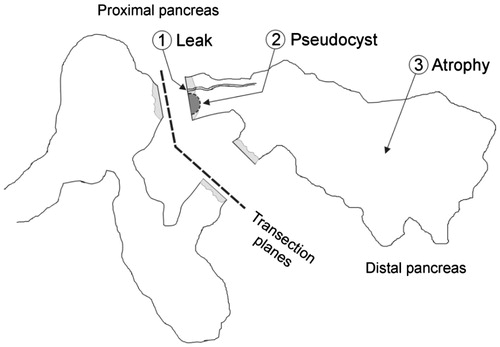

Figure 2. Main findings in the pancreas previously transected at the neck level: 1) pancreatic leak (related to the exit of main pancreatic duct) with no signs of atrophy; 2) Pseudocyst (also related to the exit of the main pancreatic duct) accompanied by partial atrophy (score 2 to 3) of the distal pancreas; and 3) Complete atrophy (score 5) of the distal zone, which occurred mostly in the cases without incidence of pancreatic fistula formation (POPF), i.e. in cases in which effective sealing of the pancreatic ducts can be expected.

Figure 3. Macroscopic and microscopic patterns founded in the distal remnant pancreas: 1) Pancreatic leak (broken arrow, A1) from the distal stump observed in animal 4 of the ST group that died on day 2 PO. The origin of the leak was easily canalised with a probe (broken arrow, A2) between some staples (arrowhead). Histologically no signs of atrophy were described (A3); 2) Pseudocyst (open arrow, B1) accompanied by partial atrophy (B2) in the distal pancreas; 3) Complete atrophy of the distal remnant pancreas (C1, C2). This occurred mostly in the RF group, in which an area of coagulative necrosis was always observed (arrow). In any case, the proximal pancreas was well preserved with no signs of atrophy (asterisk).

Overall, taking into account the above-cited definition of POPF, six animals (75%) in the ST group and one animal (14%) in the RF group were diagnosed with POPF. This difference reached statistical difference (p = 0.019) ().

Three macroscopic patterns, with their corresponding microscopic patterns in the distal remnant pancreas, were found at necropsy. These patterns were moreover related to the presence/absence of POPF (see ).

Pancreatic leak: In general, this was demonstrated at necropsy when the main pancreatic duct was injected with dye in the distal pancreas and extravasated at the same level of the pancreatic stump. However, a clinically relevant pancreatic leak was diagnosed in animal 4 of the ST group. This animal was lethargic and feverish on day 2 PO and died that night. At necropsy, there was abundant free cloudy intraperitoneal liquid with an amylase of 3956 UI L−1 (serum amylase on the same PO day: 3099 UI L−1). At the distal stump, just around some staples, a leak of presumably pancreatic fluid was clearly coming when the distal pancreas was squeezed (). In this case, the histological study of the distal pancreas revealed the complete microscopic preservation of the pancreatic architecture ().

Pseudocyst: Solitary fluid collection over the portal vein in close contact with both pancreatic stumps ( and ). The sizes of these collections ranged between 3 and 16 cm in diameter and had a defined fibrous wall at microscopic evaluation. In these collections, usually only transparent amylase-rich liquid and little or no solid material was found, so that they were then defined as pancreatic pseudocysts. Pseudocysts were observed in one animal in the RF group (animal 12) and three in the ST group (animals 2, 3 and 7). Three of these animals presented a greater than threefold drain/serum amylase ratio beyond the third PO day (). After canalisation of the main pancreatic duct in the tail and infusion of the dye solution through it, a connection was always found between the pseudocyst and the main duct from the distal pancreatic remnant. However, no connection was found between this collection and the proximal main pancreatic duct in any case. In two of the animals with pseudocysts (numbers 2 and 3) a moderate degree of acinar atrophy (score 2 to 3) was encountered in the distal pancreas. In another animal with a pseudocyst (7), the exocrine atrophy showed a lobular pattern, with lobules with no atrophy (score 0), moderate (score 3), and complete atrophy (score 5) (). Finally, one animal in the RF group (12) presented a large pseudocyst (16 cm in diameter), accompanied by a complete atrophy (score 5) of the acinar component in the distal pancreas (). Overall, a partial atrophy in the distal pancreas was usually encountered in the cases involving pseudocyst ().

Complete atrophy of the distal zone: This occurred mostly in the absence of POPF, i.e. in those cases in which effective sealing of the pancreatic duct was expected. A greater than threefold drain/serum ratio amylase was found in two animals in the ST group (5 and 6) on day 7 PO and no fluid collections were observed at autopsy (). These animals were diagnosed with POPF according to ISGPF guidelines and both had an uneventful post-operative history without fluid collection at necropsy. The microscopic evaluation of these cases as well as in the cases not diagnosed with POPF (i.e. animals 1 and 8 in the ST group, and 10, 11, 13, 15 and 16 in the RF group), showed that the acinar component had completely disappeared on day 30 PO (atrophy score 5) (). The single exception to this finding was in the animal 9 in the RF group, with an uneventful post-operative history, and no signs of POPF. In this animal we found that the ‘bridge’ of pancreatic tissue serving as an anatomical connection between the splenic and connecting lobes behind the portal vein (, marked as ‘B’) had not been completely severed. As expected, in this case the complete preservation of the distal pancreas was observed (score 0 of atrophy) ().

Common histological features of complete distal atrophy

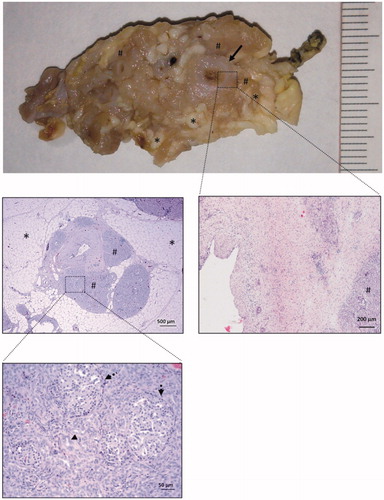

In a total of 10 animals (4 in the ST group and 6 in the RF group, see ) the acinar component had completely disappeared (atrophy score 5) and the exocrine acini had been completely replaced by pseudo-ductal complexes, based on apparently novel duct-like structures composed of low-cuboidal cells (). The ducts showed dilatation, which was most marked in the interlobular ducts or in the main duct next to the transection interface margin, and decreased distally. This feature was least notable in the intralobular ducts. In the interlobular ducts and in the main pancreatic ducts we observed epithelial metaplasia, from cylindrical to squamous and moderate periductal fibrosis which was maximal in the main pancreatic duct (). There was also marked interlobular adipose infiltration between the areas of pseudo-ductal complexes. In the atrophied pancreas, islets of Langerhans were frequently found in sections and located close to duct-like structures.

Figure 4. Common histological features of complete atrophy. The main pancreatic duct (arrow) is dilated and provided with a thick fibrotic wall. The acinar component of the pancreatic tissue has completely disappeared (atrophy score 5) and is replaced by lobules (#) of pseudo-ductal complexes with some dilated ducts (arrowheads). In these lobules, islets of Langerhans were easily seen (broken arrows). In between these lobules, there was marked interlobular adipose infiltration (asterisk).

Laboratory analysis

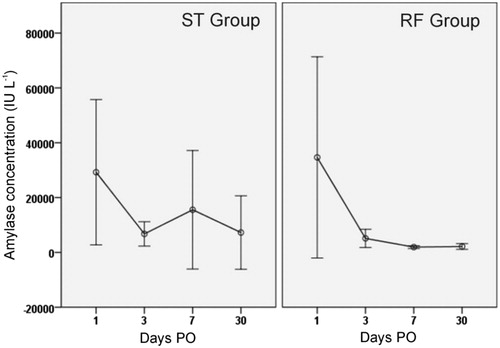

Four animals in the ST group and one in the RF group presented a greater than threefold drain/serum amylase ratio after day 3 PO (). In three of these animals (60%) a pseudocyst was observed in close contact with both pancreatic stumps at necropsy. When plotting the peritoneal amylase concentration throughout the post-operative period, it was observed that until day 3 PO these values were similar in both groups. However, after day 3 PO, these values were higher and more variable in the ST group than in the RF group (15546 IU L−1 and 7252 IU L−1 versus 1930 IU L−1 and 2152 IU L−1 for ST and RF groups on days 7 and 30, respectively) as could be expected considering the difference in POPF between the groups ( and ). However, these differences between groups did not reach statistical significance, probably because of the high variability in the ST group.

Figure 5. Peritoneal liquid amylase concentration throughout the postoperative period in both groups. Circles indicate mean values and each segment denotes 95% confidence interval of values. Note that values in the RF group are usually lower and homogeneous beyond day 3 PO.

Table 3. Pre- and post-operative serum amylase and glucose levels by group and throughout the post-operative period.

Serum amylase and glucose levels were similar in both groups throughout the post-operative period (). However, taking together both groups throughout the post-operative period, the single post-operative time that demonstrated a significantly higher level in serum amylase was on day 1 (p < 0.013). A similar analysis of serum glucose identified only the 3 h PO to be significantly higher than any other time (p < 0.0001) (immediate post-operative hyperglycaemia) ().

Discussion

POPF is known to be the most significant cause of morbidity and mortality after pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) [Citation16] and also after DP [Citation3]. Concerning PD, in a recent prospective multicentre randomised trial it was demonstrated that POPF was about 42% in the subgroup of soft pancreas and main pancreatic diameter <3 mm, regardless of the type of pancreatic anastomosis (to jejunum or to stomach) [Citation17]. Furthermore, in the same study it was demonstrated that almost 10% of these patients required re-intervention usually because of Grade C pancreatic fistula. It therefore seems there is special room for improvement in this subgroup of patients (with a normal pancreas).

It is generally accepted that if the pancreatic stump is not anastomosed (but sutured, ligated or glued) the incidence of fistula may be higher. In fact, ligation of the pancreatic stump after PD without anastomosis to the gastrointestinal tract, as originally described by Whipple, in theory could prevent a large proportion of post-operative complications since if a pancreatic fistula occurs there is no defect in the small bowel, no leakage of intestinal fluid and no activation of pancreatic enzymes [Citation2]. However, ligation of the pancreatic stump is rarely performed today, mainly because of the excessive incidence of a long-lasting fistula which could be cumbersome (sometimes in more than 50% of patients) [Citation10]. In fact, Reissman et al. [Citation9] in a controlled study after PD with duct ligation showed that it was as high as 94% and of long duration, even though it was usually well tolerated. In the last prospective randomised trial of glue occlusion of the pancreatic duct versus pancreaticojejunostomy after PD similar exocrine insufficiency were observed among the groups. It was also suggested there might be a possibly higher risk of diabetes in the occluded pancreatic duct group, even though this study was not powered to correctly evaluate this variable [Citation18]. In fact, pancreatic duct ligation has been extensively studied in the experimental setting as a model of expansion of β-cell mass − β-cell neogenesis [Citation8,Citation19]. Therefore, pancreatic duct ligation should be at least not worse than pancreaticojejunostomy in the risk of diabetes after PD. In any case, the major problem reported in ductal ligation is usually the formation of long-lasting pancreatic fistula (normally well tolerated) [Citation10]. This is why this surgical option is usually only accepted in certain ‘difficult circumstances’ [Citation10] even though it is currently employed by some groups with different indications [Citation11,Citation20].

Similarly to the above-cited clinical studies with duct ligation after PD, in our controlled experimental study we observed a high incidence (75%) of POPF after mechanical suture of the distal stump of the normal porcine pancreas when the pancreatic neck was severed. However, when RF coagulation of the neck of the pancreas was performed prior to the section this incidence was dramatically reduced to 14%, which led to better recovery of the animal as demonstrated by a higher post-operative crude weight gain and no mortality in this group (see and ).

The higher efficiency of RF-induced thermal coagulation over mechanical suture on sealing the pancreatic stump matches well with recent data from clinical [Citation4] and experimental [Citation6,Citation7] studies with RF-assisted distal pancreatectomy versus stapler occlusion technique. The better efficiency on sealing the pancreatic stump with RF-based devices and other hyperthermic systems may be due to eliciting fibrosis and collagen shrinkage secondary to coagulative thermal necrosis, leading to the sealing of the ducts and vessels as previously described [Citation4,Citation7,Citation21–25]. Similar results were seen in the present study in the RF group, in which we found round-shaped areas of coagulation thermal necrosis completely surrounded by a dense layer of mature connective tissue on both transection planes.

To our knowledge, this is the first attempt at comparing RF-induced heating and mechanical stapler to close the pancreatic stump closure using a large animal model in which the distal pancreas was left without any drainage of the main pancreatic duct. In a recent study we performed a similar RF-assisted transection of the pancreatic neck on a murine model, and we observed that most of the acinar cells were rapidly and massively deleted by p53-dependent apoptosis (peaked on day 3 PO) by caspase activation with some pancreatic epithelial proliferation and beta-cell neogenesis [Citation26]. That study further demonstrated that this experimental model based on RF-assisted transection of pancreas did not lead to necrotising pancreatitis. Similarly, in the present study on the porcine pancreas we found an increase in serum amylase levels (p < 0.05) on day 3 PO over their preoperative value with no clinical repercussions, which returned to levels similar to baseline in the following weeks (). Probably as a result of this massive deletion of the exocrine pancreas, on day 30 PO almost complete atrophy of the exocrine distal pancreas as compared to the proximal pancreas was observed when the main pancreatic duct was efficiently sealed. However, four animals in the ST group showed some degree of partial preservation of the exocrine pancreas. In fact, all the animals with a low degree of atrophy had some kind of evident failure of the main pancreatic duct as was shown by dye extravasation from the pancreatic stump at necropsy in the form of free pancreatic leak (one case) or pseudocyst (three cases) ().

Study limitations

Despite that this study was performed on large animals (similar to human pancreas), there are some differences in the size and anatomy of the pancreas between both species that could be relevant and may outweigh the benefits of the procedure described. The RF device was used with a mean transection time of 5 min. It is unclear whether a longer coagulation time or a different RF electrode design would improve the sealing efficiency of the pancreatic stump.

It has been reported that the use of bioabsorbable staple line reinforcement products reduces the incidence of POPF after DP versus non-reinforced stapled resection [Citation27]. In this respect, we could have designed an experimental group of reinforced stapler. However, we decided to employ simply staplers because our objective was to compare RF-induced heating versus a simple mechanical suture without the possible inflammatory reaction due to a bioabsorbable material. A recent study comparing traditional suture, reinforced stapling, and (saline-linked) RF-heating reported a similar incidence of POPF (range 25–26%) in DP [Citation28]. Future studies should be aimed to compare the reinforced stapling versus RF-heating in experimental models prone to pancreatic fistula formation as employed here.

Conclusions

The experimental findings suggest that RF-induced heating applied to the transection plane on the neck of the pancreas provides more effective sealing of the stump than a mechanical suture, and leads to complete atrophy of the distal remnant pancreas. Given that this model has a high risk of fistula formation, the information obtained could be of interest in managing the pancreas remnant after distal pancreatectomy or even after pancreaticoduodenectomy in certain circumstances.

Declaration of interest

This work was supported by the Spanish ‘Programa Estatal de Investigación, Desarrollo e Innovación Orientada a los Retos de la Sociedad’ under grant TEC2014-52383-C3-R (TEC2014-52383-C3-3-R). F.B., R.Q. and E.B. declare stock ownership in Apeiron Medical S.L., a company that has a license for the patent US 8.303.584.B2, on which the device tested in this study is based. The other authors report no conflict of interests or financial ties to disclose. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Schoellhammer HF, Fong Y, Gagandeep S. Techniques for prevention of pancreatic leak after pancreatectomy. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr 2014;3:276–87

- Tran KT, Smeenk HG, van Eijck CH, Kazemier G, Hop WC, Greve JW, et al. Pylorus preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy versus standard Whipple procedure: A prospective, randomized, multicenter analysis of 170 patients with pancreatic and periampullary tumors. Ann Surg 2004;240:738–45

- Diener MK, Seiler CM, Rossion I, Kleeff J, Glanemann M, Butturini G, et al. Efficacy of stapler versus hand-sewn closure after distal pancreatectomy (DISPACT): A randomised, controlled multicentre trial. Lancet 2011;377(9776):1514–22

- Blansfield J, Rapp M, Chokshi R. Novel method of stump closure for distal pancreatectomy with a 75% reduction in pancreatic fistula rate. J Gastroint Surg 2012;16:524–8

- Nagakawa Y, Tsuchida A, Saito H, Tohyama Y, Matsudo T, Kawakita H, et al. The VIO soft-coagulation system can prevent pancreatic fistula following pancreatectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2008;15:359–65

- Truty MJ, Sawyer MD, Que FG. Decreasing pancreatic leak after distal pancreatectomy: Saline-coupled radiofrequency ablation in a porcine model. J Gastrointest Surg 2007;11:998–1007

- Dorcaratto D, Burdío F, Fondevila D, Andaluz A, Quesada R, Poves I, et al. Radiofrequency is a secure and effective method for pancreatic transection in laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy: Results of a randomized, controlled trial in an experimental model. Surg Endosc 2013;27:3710–19

- Quesada R, Andaluz A, Cáceres M, Moll X, Iglesias M, Dorcaratto D, et al. Long-term evolution of acinar-to-ductal metaplasia and β-cell mass after radiofrequency-assisted transection of the pancreas in a controlled large animal model. Pancreatology 2016 Nov 18.; pii: S1424-3903(15)00684-5. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2015.10.014. [Epub ahead of print]

- Reissman P, Perry Y, Cuenca A, Bloom A, Eid A, Shiloni E, et al. Pancreaticojejunostomy versus controlled pancreaticocutaneous fistula in pancreaticoduodenectomy for periampullary carcinoma. Am J Surg 1995;169:585–8

- Fromm D, Schwarz K. Ligation of the pancreatic duct during difficult operative circumstances. J Am Coll Surg 2003;197:943–8

- Theodosopoulos T, Dellaportas D, Yiallourou AI, Gkiokas G, Polymeneas G, Fotopoulos A. Pancreatic remnant occlusion after Whipple’s procedure: An alternative oncologically safe method. ISRN Surg 2013;2013:960424

- Ferrer J, Scott WE III, Weegman BP, Suszynski TM, Sutherland DE, Hering BJ, Papas KK. Pig pancreas anatomy: Implications for pancreas procurement, preservation, and islet isolation. Transplantation 2008;86:1503–10

- Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, et al. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: An international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery 2005;138:8–13

- Gibson-Corley KN, Olivier AK, Meyerholz DK. Principles for valid histopathologic scoring in research. Vet Pathol 2013;50:1007–15

- Altman D. Practical statistics for medical research. London: Chapman & Hall, 1991

- Fuks D, Piessen G, Huet E, Tavernier M, Zerbib P, Michot F, et al. Life-threatening postoperative pancreatic fistula (grade C) after pancreaticoduodenectomy: Incidence, prognosis, and risk factors. Am J Surg 2009;197:702–9

- Pessaux P, Sauvanet A, Mariette C, Paye F, Muscari F, Cunha AS, et al. External pancreatic duct stent decreases pancreatic fistula rate after pancreaticoduodenectomy: Prospective multicenter randomized trial. Ann Surg 2011;253:879–85

- Tran K, Van Eijck C, Di Carlo V, Hop WCJ, Zerbi A, Balzano G, et al. Occlusion of the pancreatic duct versus pancreaticojejunostomy: A prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg 2002;236:422–8

- Chung C-H, Hao E, Piran R, Keinan E, Levine F. Pancreatic β-cell neogenesis by direct conversion from mature α-cells. Stem Cells 2010;28:1630–8

- Farsi M, Boffi B, Cantafio S, Miranda E, Bencini L, Moretti R. Trattamento del moncone pancreatico dopo duodenocefalopancreasectomia: occlusione del Wirsung vs anastomosi pancreatico-digiunale. [Treatment of the pancreatic stump after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Wirsung duct occlusion versus pancreaticojejunostomy]. Minerva Chir 2007;62:225–33

- Fronza JS, Bentrem DJ, Baker MS, Talamonti MS, Ujiki MB. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy using radiofrequency energy. Am J Surg 2010;199:401–4

- Rempp H, Voigtländer M, Clasen S, Kempf S, Neugebauer A, Schraml C, et al. Increased ablation zones using a cryo-based internally cooled bipolar RF applicator in ex vivo bovine liver. Invest Radiol 2009;44:763–8

- Hanly EJ, Mendoza-Sagaon M, Hardacre JM, Murata K, Bunton TE, Herreman-Suquet K, et al. New tools for laparoscopic division of the pancreas: A comparative animal study. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2004;14:53–60

- Hartwig W, Duckheim M, Strobel O, Dovzhanskiy D, Bergmann F, Hackert T, et al. LigaSure for pancreatic sealing during distal pancreatectomy. World J Surg 2010;34:1066–70

- Suzuki Y, Fujino Y, Tanioka Y, Hori Y, Ueda T, Takeyama Y, et al. Randomized clinical trial of ultrasonic dissector or conventional division in distal pancreatectomy for non-fibrotic pancreas. Br J Surg 1999;86:608–11

- Quesada R, Burdío F, Iglesias M, Dorcaratto D, Cáceres M, Andaluz A, et al. Radiofrequency pancreatic ablation and section of the main pancreatic duct does not lead to necrotizing pancreatitis. Pancreas 2014;43:1–7

- Yamamoto M, Hayashi MS, Nguyen NT, Nguyen TD, McCloud S, Imagawa DK. Use of Seamguard to prevent pancreatic leak following distal pancreatectomy. Arch Surg 2009;144:894–9

- Ceppa EP, McCurdy RM, Becerra DC, Kilbane EM, Zyromski NJ, Nakeeb A, et al. Does pancreatic stump closure method influence distal pancreatectomy outcomes? J Gastrointest Surg 2015;19:1449–56