Abstract

Objective. Few studies have analysed adherence to antibiotic treatment in pharyngitis. The aim of this study was to evaluate the association of rapid antigen detection tests (RADT) and treatment adherence among patients 18 years of age or over with pharyngitis treated with different antibiotic regimens. Design. Prospective study from 2003 to 2008. Setting. Office-based physician practices. Intervention. The adherence of patients prior to the use of RADTs – no test was available until mid-2006 – was compared with the adherence associated with the use of RADTs. Subjects. Patients with suspected streptococcal pharyngitis. Main outcome measures. Patient adherence was assessed by electronic monitoring. The adherence outcomes considered were antibiotic-taking adherence, correct dosing, and good timing adherence during at least 80% of the antibiotic course. Results. A total of 196 patients were recruited. The percentage of container openings was 77.9%±17.7%, being significantly higher for patients in whom the RADTs were performed compared with those in whom this test was not undertaken (80.1% vs. 70.8% for thrice-daily antibiotic regimens and 88.1% vs. 76.5% for twice-daily regimens; p < 0.01). The other variables of adherence were also better among patients undergoing RADT in both those who took at least 80% of the pills (71.3% vs. 42.2%; p < 0.001) as well as those with good timing adherence (52.5% vs. 32.8%; p < 0.01). Furthermore, correct dosing was always greater when the patient had undergone an RADT. Conclusion. Adherence to antibiotic treatment is higher when an RADT is carried out at the consultation prior to administration of antibiotic treatment.

It is known that adherence to antibiotic therapy is low in pharyngitis and the factors most associated with better antibiotic treatment adherence are the number of daily doses and the length of the treatment regimen.

This study investigates the association of rapid antigen detection tests with adherence in patients with suspected streptococcal pharyngitis.

Adherence to antibiotic treatment is better when the physician uses rapid antigen detection tests in the office prior to the administration of the antibiotic than when antibiotic treatment is prescribed following the normal practice of not using rapid tests.

The greater adherence observed with the use of rapid tests disappears after the sixth day of antibiotic treatment, probably coinciding with the fact that patients feel better.

Many studies have been performed on therapeutic adherence in chronic diseases but there are fewer on acute processes such as infectious diseases [Citation1]. Pharyngitis is one of the most common reasons for primary care consultations in industrialized countries and antibiotics are prescribed in most cases [Citation2,Citation3]. One meta-analysis found that 37.8% of patients forget to take some doses of antibiotics [Citation4]. Poor adherence to antibiotic regimens has been identified as a major cause of treatment failure [Citation5]. In addition, from a community perspective, non-adherence leads to storing of antibiotics at home which induces self-medication and produces a vicious circle and thereby favours the emergence of bacterial resistance [Citation6]. The factors which most influence patients to take their medications inappropriately are the number of daily doses and the length of treatment. In a previous paper published in a local journal with a lower number of cases, we reported that non-adherence is greater in accordance with the higher number of doses per day in pharyngitis [Citation7].

Adherence may be measured directly and indirectly. Indirect methods evaluate adherence from information provided by patients through measurement of events or circumstances that are probably or indirectly related to adherence. The main inconvenience of these methods is that the information is usually provided by the patients themselves and in general overestimate the real adherence. Of all the indirect methods used, overestimation of patient adherence is lowest with electronic monitoring [Citation8]. In Scandinavian countries rapid antigen detection tests (RADT) are widely performed, accounting for up to one-quarter of all the cases with respiratory tract infections [Citation9]. However, in Southern Europe antibiotic treatment is usually prescribed on the basis of the data of the clinical history and physical examination, with the use of point-of-care tests being infrequent in our setting. Nonetheless, RADTs have been introduced in our country in recent years for the diagnosis of streptococcal pharyngitis. These rapid tests have been shown to lead to a reduction in the prescription of antibiotics [Citation10]. Nevertheless, it is not known whether their performance is associated with greater adherence or not. Thus, the present study was undertaken to analyse the association between the use of RADTs and adherence to antibiotic treatment in pharyngitis.

Material and methods

We performed a prospective, observational study undertaken in five general medicine outpatient clinics from 2003 to 2008. We recruited patients 18 years of age or older with suspected streptococcal pharyngitis. All patients with a sore throat and three or more of the Centor criteria – history of fever, tonsillar exudates, tender cervical nodes, and/or absence of cough – were invited to participate. In mid-2006 all the primary care practices were provided with RADTs for the diagnosis of pharyngitis caused by Group A β-haemolytic streptococcus. All the physicians were recommended not to prescribe antibiotics with negative RADT results. However, the physicians were free to choose whether to use these rapid tests in their consultation, or to use antibiotics or not and, furthermore, the physicians decided which antibiotic treatment was to be administered.

Electronic monitoring

Different antibiotics were included in MEMS6 containers (Medication Event Monitoring System, Aardex Ltd, Zug, Switzerland). The MEMS consists of a standard container for tablets with a screw top inside which an electronic microcircuit is placed. This device records when the medication container is opened. The patients gave informed consent to participate in a study on the rational use of antibiotics, with emphasis on the importance of taking all the pills included in the container following the instructions they had received. All the patients were recommended to take one pill except in the case of penicillin V (600 000 IU) and the new pharmacokinetically enhanced formulation of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (1000/62.5 mg), in which case they were instructed to take two pills every 12 hours. All the patients were provided with complete information on the characteristics of the study and their participation, but were not informed at this time about the future assessment of adherence to avoid bias in the results. When they returned to the clinic, adherence was evaluated and the patients were fully informed of the results and permission was requested to include these data anonymously in the current report. The data contained in the microprocessors were transferred to the computer and processed with the PowerView program v. 1.3.2. (Aardex Ltd). Multiple openings of the container within a period of less than 15 minutes were not counted.

Adherence parameters

Three outcome measures were taken into account in this paper [Citation11]:

Taking adherence, calculated as the percentage of times the container was opened during the course of the treatment based on the pills contained in the containers. The percentage of patients who opened the container at least 80% of the times was also calculated.

Correct dosing, calculated as the number of days on which the patient opened the container the satisfactory number of times, at least twice for patients treated with twice-daily antibiotic regimens and at least three times for those assigned to thrice-daily antibiotic regimens.

Good timing adherence during at least 80% of the antibiotic course, indicating whether the openings of the container coincided with the times recommended: intervals of 8+4 h during at least 80% of the thrice-daily course of antibiotic treatment and 12+6 h intervals during at least 80% of the antibiotic course for the twice-daily antibiotics.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive analysis of the study variables was performed before applying non-parametric Mann–Whitney tests to compare means and Fisher’s exact test to compare categorical variables, with differences being considered as statistically significant with p < 0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

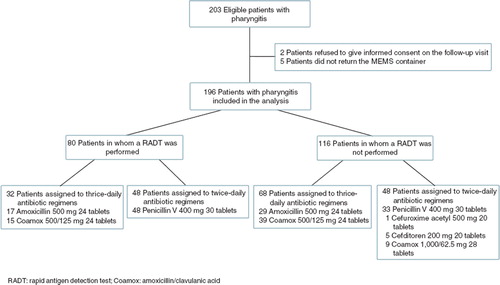

A total of 203 patients were recruited. However, two patients withdrew consent to analyse the data and another five did not return the container. The mean age was 29.1±10.4 years, being slightly lower among the patients in whom an RADT was performed (27.5±8.8 years). A total of 104 patients were women (53.1%) and 68 were smokers (34.7%), with no differences in the use of RADT (). Of the 196 patients in whom data on adherence were obtained, the antibiotic treatment was administered on the basis of clinical criteria in 116 (59.2%), while in the remaining 80 patients (40.8%) the antibiotic treatment was administered with a positive RADT result. A total of 123 patients presented three Centor criteria and 73 presented four (37.2%). Among the latter, the RADT was performed in 31 (42.5%) while StrepA was undertaken in 49 patients (39.8%) with three criteria. shows the flow of patients with each of the infections and the antibiotic schedules received. One antibiotic treatment failure (0.5%) was observed, requiring a change in antimicrobial treatment. Six cases demonstrated manifest non-adherence with five or less openings of the container. Five patients opened the container more than once at intervals of < 15 minutes.

Table I. Sociodemographic and adherence parameters observed in patients with pharyngitis depending on the use of rapid antigen detection tests

Data on adherence

shows the comparison of the data on adherence depending on the use of RADTs in the consultations. The percentage of openings of the MEMS containers ranged from a mean of 82.3%±19.4% for patients with the twice-daily antibiotic regimens to 73.8%±14.8% which was observed with the thrice-daily antibiotic regimens (p < 0.001). In both cases, the percentage of openings was greater among the patients undergoing the RADT, with 88.1%±14.7% of openings among the patients assigned twice-daily antibiotics submitted to RADT, and was significantly higher than in the patients who did not undergo the rapid test (76.5%±21.8%; p < 0.01). For the patients assigned thrice-daily antibiotic regimens these percentages were 80.1%±11.8% and 70.8%±15.2%, respectively (p < 0.01). The other variables of adherence were also better in the patients undertaking StrepA in both those who took at least 80% of the pills (71.3% vs. 42.2%; p < 0.001) as well as those with good timing adherence (52.5% vs. 32.8%, respectively; p < 0.01). The percentage of pills taken was slightly higher among the patients presenting four criteria (80.5%) compared with those presenting three criteria (76.4%), with no statistically significant differences being found. Likewise, the percentage of patients who took at least 80% of the pills was slightly higher in the first group (56.2% vs. 52.8%).

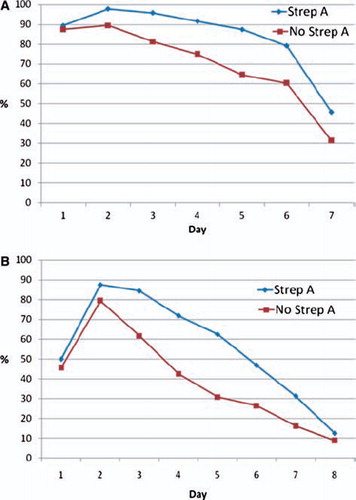

The percentage of patients who opened the container a satisfactory number of times throughout the treatment course was always greater when the patient had undergone a rapid test prior to the administration of the antibiotic (). For both the twice-daily and thrice-daily antibiotic regimens, the difference between those who underwent the RADTs and those who did not was statistically significant for days 3, 4, 5, and 6 of the antibiotic schedule, observing a maximum difference on the fifth day (p < 0.01). The differences disappeared after the sixth day of the antibiotic treatment schedule.

Figure 2. Correct dosing. (A) Percentage of patients who opened the MEMS containers the satisfactory number of times (at least twice) in pharyngitis treated with twice daily antibiotic regimens depending on the use of RADT. Not all the patients began to take the antibiotic in the morning of the first day. (B) Percentage of patients who opened the MEMS containers the satisfactory number of times (at least three times per day) in pharyngitis treated with thrice daily antibiotic regimens depending on the use of RADT. Not all the patients began to take the antibiotic in the morning of the first day.

Discussion

Summary of main findings

This study demonstrates that patient adherence to antibiotic treatment is poor in suspected streptococcal pharyngitis. On the other hand, the use of RADT prior to the prescription of an antibiotic is associated with better parameters of adherence than when these tests are not used.

Strengths and weaknesses

This was not a clinical trial. The objective of the study was not to compare whether performing an RADT during the consultation improved the adherence of the patients to antibiotic treatment or not, but rather it was limited to observing whether the patients took the antibiotic treatment or not and determining a possible association with the use of these tests. Another limitation is patient expectation of an antibiotic. This aspect was not considered in our study and patients’ expectations of receiving an antibiotic, known to be an important determinant of prescribing, may also be associated with the use of RADT and adherence. On the other hand, in most cases the diagnosis was clinical and although, on most occasions, clinical pictures with a supposedly bacterial aetiology were included, all the infections included may not have actually been of this origin.

As participants were not allocated to the different study groups randomly, some differences in demographic variables may have been observed between these groups. Thus, for example, a slightly higher percentage of RADTs were performed in patients with four criteria than in those with three. The parameters of adherence were somewhat better in the patients with four criteria, although no statistically significant differences were observed. Furthermore, a lower mean age was observed in patients who underwent RADT but the differences were not statistically significant probably because more bacterial infections were included in the first case than in the second and it is known that younger patients more often present with streptococcal infection [Citation12]. However, based on the evidence of studies on therapeutic compliance with antibiotic therapy, age and gender do not have or have very little influence on antimicrobial treatment adherence [Citation4,Citation5,Citation13].

Furthermore, it cannot be guaranteed that the medication was actually taken each time the MEMS container was opened. Nonetheless, we believe that the electronic method used and the fact that the patients were not informed as to the real objective of the study until the second visit, which has not been done previously, undoubtedly constitutes the greatest strength of this study.

Implications for further research

To our knowledge this is the first time that an association has been described between the use of RADTs and better outcomes of adherence. Since this is not a clinical trial no relationship of causality may be inferred, but it does demonstrate an association between the use of rapid testing and adherence. The use of rapid tests is commonly regarded by primary care physicians as valuable for convincing patients not to take antibiotics [Citation14]. Similarly, the fact of explaining to the patients that they have a greater probability of presenting a bacterial infection may be a clearer persuasion as to the need to take the medication. However, it was curious to observe that the greater adherence observed with the use of rapid tests was only observed on the first days of antibiotic treatment and was no longer significant after the sixth day of the antibiotic schedule. It is likely that after a few days of feeling well the patients discontinued the antibiotic treatment regardless of whether they had undergone the RADT.

In most clinical situations, particularly in the case of antibiotic therapy, the time interval between doses is extremely important. In most cases, the pharmacokinetics of the drugs makes it necessary for them not to be taken later than indicated to ensure maximum therapeutic action [Citation15]. A prolonged time interval between doses has been found to lead not only to reduced effectiveness but also to the emergence of antibiotic-resistant pathogens [Citation16]. Few experimental studies have been performed with antibiotic treatments with the objective of improving the adherence of the patients to antibiotic treatment in upper respiratory tract infections [Citation17]. Only Colcher and Bass reported increased adherence with an antibiotic regimen for streptococcal pharyngitis with a relatively simple strategy of counselling patients about the importance of full adherence, reinforced by written instructions [Citation18]. Despite not being a clinical trial, the present study demonstrates how a simple technique such as the performance of RADTs prior to the prescription of an antibiotic is associated with greater therapeutic adherence. The results of this study may be of interest for the design of future clinical trials to determine whether a strategy such as that reported here is able to improve therapeutic adherence to antibiotic treatment and determine how this could reduce bacterial resistance.

Funding body

The MEMS containers were provided through a grant from GlaxoSmithKline. On the other hand, the StrepA was provided free of charge by Leti and Genzyme. The authors declare that did not receive any direct economic support for undertaking this study.

Competing interests

None declared.

References

- McDonald HP, Garg AX, Haynes RB. Interventions to enhance patient adherence to medication prescriptions: Scientific review. JAMA 2002;288:2868–79.

- McCraig LF, Hughes JM. Trends in antimicrobial drug prescribing among office-based physicians in the United States. JAMA 1995;273:214–19.

- Gjelstad S, Dalen I, Lindbaek M. GPs’ antibiotic prescription patterns for respiratory tract infections: Still room for improvement. Scand J Prim Health Care 2009;27:208–15.

- Kardas P, Devine S, Golembesky A, Roberts C. A systematic review and meta-analysis of misuse of antibiotic therapies in the community. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2005;26: 106–13.

- Sclar DA, Tartaglione TA, Fine MJ. Overview of issues related to medical adherence with implications for the outpatient management of infectious diseases. Infect Agents Dis 1994; 3:266–73.

- Vrijens B, Urquhart J. Patient adherence to prescribed antimicrobial drug dosing regimens. J Antimicrob Chemother 2005;55:616–27.

- Llor C, Sierra N, Hernández S, Moragas A, Hernández M, Bayona C [Compliance rate of antibiotic therapy in patients with acute pharyngitis is very low, mainly when thrice-daily antibiotics are given]. Rev Esp Quimioter 2009;22:20–4.

- Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med 2005;353:487–97.

- Engström S, Mölstad S, Lindström K, Nilsson G, Borqquist L. Excessive use of rapid tests in respiratory tract infections in Swedish primary health care. Scand J Infect Dis 2004;36:213–18.

- Maltezou HC, Tsagris V, Antoniadou A, Galani L, Douros C, Katsarolis I, . Evaluation of a rapid antigen detection test in the diagnosis of streptococcal pharyngitis in children and its impact on antibiotic prescription. J Antimicrob Chemother 2008;62:1407–12.

- Cals JW. Comment on: The higher the number of daily doses of antibiotic treatment in lower respiratory tract infection the worse the compliance. J Antimicrob Chemother 2009;63: 1083–4.

- McIsaac WJ, Goel V, To T, Low DE. The validity of a sore throat score in family practice. CMAJ 2000;163:811–5.

- Anastasio GD, Little Jr JM, Robinson MD, Pettice YL, Leitch BB, Norton UJ. Impact of compliance and side effects on the clinical outcome of patients treated with oral erythromycin. Pharmacotherapy 1994;14:229–34.

- Butler CC, Simpson S, Wood F. General practitioners’ perceptions of introducing near-patient testing for common infections into routine primary care: A qualitative study. Scand J Prim Health Care 2008;26:17–21.

- Craig WA. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic parameters: Rationale for antibacterial dosing of mice and men. Clin Infect Dis 1998;26:1–12.

- Thomas JK, Forrest A, Bhavnani SM, Hyatt JM, Cheng A, Ballow CH, . Pharmacodynamic evaluation of factors associated with the development of bacterial resistance in acutely ill patients during therapy. Antimicr Agents Chemother 1998;42:521–7.

- Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, McDonald HP, Yao X. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;(2):CD000011.

- Colcher IS, Bass JW. Penicillin treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis: A comparison of schedules and the role of specific counseling. JAMA 1972;222:657–9.