Abstract

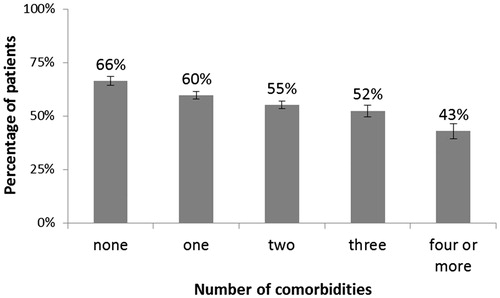

Objective To the authors’ knowledge, there are few valid data that describe the prevalence of comorbidity in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients seen in family practice. This study aimed to investigate the prevalence of comorbidities and their association with elevated (≥ 7.0%) haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) using a large sample of T2DM patients from primary care practices. Design A cross-sectional study in which multivariate logistic regression was applied to explore the association of comorbidities with elevated HbA1c. Setting Primary care practices in Croatia. Subjects Altogether, 10 264 patients with diabetes in 449 practices. Main outcome measures Comorbidities and elevated HbA1c. Results In total 7979 (77.7%) participants had comorbidity. The mean number of comorbidities was 1.6 (SD 1.28). Diseases of the circulatory system were the most common (7157, 69.7%), followed by endocrine and metabolic diseases (3093, 30.1%), and diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue (1437, 14.0%). After adjustment for age and sex, the number of comorbidities was significantly associated with HbA1c. The higher the number of comorbidities, the lower the HbA1c. The prevalence of physicians’ inertia was statistically significantly and negatively associated with the number of comorbidities (Mann–Whitney U test, Z = –12.34; p < 0.001; r = –0.12). Conclusion There is a high prevalence of comorbidity among T2DM patients in primary care. A negative association of number of comorbidities and HbA1c is probably moderated by physicians’ inertia in treatment of T2DM strictly according to guidelines.

There is a high prevalence of comorbidity among T2DM patients in primary care.

Patients with breast cancer, obese patients, and those with dyslipidaemia and ischaemic heart disease were more likely to have increased HbA1c.

The higher the number of comorbidities, the lower the HbA1c.

Key points

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a lifelong disease that represents a major public health problem worldwide. Maintaining normal blood glucose level is the main target for disease management with haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) < 7% or ≤ 6.5% set as a goal.[Citation1,Citation2] Normalizing HbA1c level can reduce DM-related morbidity and mortality as well as the incidence and progression of complications.[Citation3] Yet, large proportions of patients with diabetes do not achieve target values, and effective diabetes management often presents an enormous challenge.

One of the challenges is the increasing extent of comorbidity. Comorbidity refers to the presence of at least one extra chronic disease along with a chronic disease of interest lasting for six months or longer.[Citation4] Comorbidity is a regular feature of general practice with four or more conditions together in 55% of patients over the age of 75 years.[Citation5] Most adults with diabetes have at least one morbid chronic disease, and 40% have three or more.[Citation6,Citation7] The importance of treating patients with T2DM to target glycaemic levels applies to patients with and without comorbidities in the same way. However, evidence-based diagnostic and treatment strategies generally overlook comorbidity. Only recently, a position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) has suggested individualized and tailored care for T2DM, taking into account several elements, including comorbidities.[Citation8] Comorbid conditions may shift the priority away from diabetes as a priority and complicate patients’ self-management.[Citation9]

Studies have examined the association between chronic comorbid conditions and glycaemic control. However, findings concerning the relationship between comorbidity and glycaemic control are conflicting. In some cases, patients with the greatest clinical complexity were more likely (than less complex patients) to receive high-quality diabetes care, whereas other data suggest that comorbidity is associated with lower glycaemia control.[Citation10,Citation11] There are different ways of measuring comorbidity, from indices that estimate a comorbidity score to simply counting the number of coexisting diseases within a person, using a predefined list of medical conditions.[Citation12] Identification of an index disease is often neither obvious nor useful for the primary care physician.[Citation13] Recently, the level of achieved glycaemic control in T2DM patients became part of the payment for primary care physicians in Croatia, but again with no regard to comorbidity.[Citation14]

Given the above-mentioned research studies and the fact that available data on this subject in Croatia are scarce, the purpose of this study was to estimate the prevalence of comorbidity in T2DM patients. We aimed to evaluate the association between the number and type of comorbidities and elevated HbA1c, using a large sample of T2DM patients from primary care practices in Croatia.

Material and methods

Study design, setting, and participants

We used the data from a national, multi-centre, cross-sectional study that was conducted in a complex, two-stage sample of T2DM patients seen in 449 primary care centres in Croatia between 2008 and 2010. The target population of general practitioners (GPs) consisted of 2552 individuals working in the family medicine service in 2007. A stratified proportional, random sample of 500 GPs was initially chosen. Two stratification criteria were included: practice size (≤1399 patients, 1400–1799 patients, ≥1800 patients) and geographical distribution of practices (21 Croatian counties). The selection of practices and GPs was made using the data from the Croatian National Institute of Public Health and Croatian Health Insurance.[Citation15] GPs were instructed to obtain a consecutive sample of T2DM patients diagnosed at least three years prior to study entry, aged ≥40 years, who visited a practice for diabetes control. Each GP was instructed to choose a sample of n = 25 patients. GPs completed a questionnaire with patients’ data on all comorbidities, using the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10). ICD-10 has been the standard coding system in Croatia since 1994. Physicians’ clinical inertia was defined as failure to change the therapy although the HbA1c level indicated a need for change. Patients were informed of the purpose of the study and were told that the study was anonymous and that they had the possibility to refuse to participate. After completing the questionnaire HbA1c was assessed. For the measurement of HbA1c, an inhibition of latex immunoagglutination with the DCA Vantage analyser from Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics® (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) was used. All measurements were done by the GP. We divided HbA1c into two categories: elevated (≥ 7.0%), and normal (< 7.0%).

The study protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Medical School, University of Zagreb review board, and the study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants gave informed consent.

Statistical analysis

Normality of distribution was tested using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Mean and standard deviation were used to measure central tendency and dispersion. We used a multivariate, binary logistic regression to explore the association of chronic diseases with elevated HbA1c. We excluded chronic diseases with a prevalence of less than 1%. Association of the number of comorbidities with physicians’ clinical inertia was analyded using Mann–Whitney U test with r given as the standardized measure of the effect size calculated as Z/SQRT(n), where Z is the Mann–Whitney test statistic and n is the sample size. Association of particular comorbidities with patients’ sex was analysed by chi-square test. Association of the number of comorbidities and diabetes complications with patients’ age was assessed by Spearmen’s rank correlation coefficient (ρ). Statistical significance level was set at α = 0.05 in all analyses. In all instances we used two-tailed tests. The statistical analysis was performed using MedCalc Statistical Software version 15.6.1 (MedCalc bvba, Ostend, Belgium), and R version 3.2.1.

Results

We studied comorbidity prevalence in a large sample of 10 264 T2DM patients treated in primary care in Croatia. Of 500 primary care physicians who were invited to participate, 44 (8.8%) refused and seven (1.4%) were excluded for other reasons. Finally, a sample of 449 primary care physicians was included. A total of 10 335 patients was assessed for eligibility. For different reasons 50 (0.5%) were excluded, and in an additional 21 (0.2%) data on HbA1c were not properly collected. The final sample consisted of 4927 (48.0%) male, and 5327 (52.0%) female patients; data on sex were not properly recorded for 10 (0.1%) patients. Their mean (SD) age was 65.7 (10.05) with female patients somewhat older than the male ones (). Our sample was representative for two parameters that were used in stratification (county, practice size). The representativeness for other parameters could not be checked as valid and reliable population data were not available.

Table 1. Characteristics of patients and practices included in the study.

A total of 7979 (77.7%) participants had some comorbid disease with the mean number of comorbidities being 1.6 (SD 1.28). The largest number of comorbidities recorded for a patient was 18. Diseases of the circulatory system were the most common (7157, 69.7%), followed by endocrine and metabolic diseases (3093, 30.1%) and diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue (1437, 14.0%). Among the top 10 recorded comorbidities were mental and behavioural disorders (526, 5.1%), diseases of the digestive system (493, 4.8%), diseases of the genitourinary system (450, 4.4%), diseases of the respiratory system (449, 4.4%), diseases of the eye and ocular appendages (492, 4.8%), and neoplasms (104, 1.0%). The analysis of comorbidities prevalence by sex revealed disorders of the thyroid gland, depression, hypertension, cardiomyopathy, arthrosis and osteoporosis to be more prevalent in female participants while ischaemic heart diseases and gout are more prevalent in male participants (). A total of 5380 (53.1%) participants had diabetes complications: polyneuropathy (3138, 32.4%), coronary disease (1692, 17.2%), retinopathy (1241, 12.6%), nephropathy (557, 5.6%), non-healing wounds (127, 1.3%), and amputation (86, 0.9%).

Table 2. Number and prevalence of comorbidities (n = 10 264).

Both the number of comorbidities and diabetes complications were statistically significantly associated with patients’ age (Spearmen’s Rho, ρ = 0.20; p < 0.001 and ρ = 0.15; p < 0.001 respectively). The number of comorbidities varied from mean (SD) 0.9 (1.04) in the patient age group 40–49 to 1.9 (1.25) in the > 80 age group. The prevalence of obesity and disorders of lipoprotein metabolism are the only two conditions that decrease with age ().

Table 3. Prevalence of comorbidities in different age groups (n = 10 264).

A total of 4233 (41.2%) participants had HbA1c < 7% and 2808 (27.4%) had HbA1c < 6.5%. After adjustment for physician’s age, sex, years of service, specialization in family medicine, the number of patients examined daily, the total number of patients diagnosed with diabetes, and inertia in treatment of diabetes as well as for patients’ age and sex, the duration of diabetes and the total number of comorbidities, breast cancer, obesity, disorders of lipoprotein metabolism, and ischaemic heart disease were positively associated with elevated HbA1c (). The highest association of any studied variable with elevated HbA1c was observed in the case of physicians’ inertia in treatment of T2DM.

Table 4. Multivariate binary logistic regression of comorbidities and possible confounders to elevated HbA1c.

The prevalence of physicians’ inertia was statistically significantly and negatively associated with the number of comorbidities (Mann–Whitney U test, Z = –12.34; p < 0.001; r = –0.12) ().

Discussion

Our study demonstrated a high prevalence of comorbidity among T2DM patients. It also showed that patients with breast cancer, obese patients, and those with dyslipidaemia and ischaemic heart disease were more likely to have increased HbA1c. As the number of comorbidities was higher, patients were less likely to have increased HbA1c.

Taking into account the differences in comorbidity definitions and measures in different studies, our finding of a 78% prevalence of diabetes non-related comorbidity is comparable with findings in other studies.[Citation16,Citation17] Our study confirms that in primary care a patient with diabetes and no other medical problem is an exception rather than a rule. With more than 17% of the Croatian population being over 65 years of age, the prevalence of both diabetes and comorbid illnesses is likely to increase.[Citation18] From a public health perspective this may have important implications for health care policy in Croatia. There is a broad consensus that comorbidity and its high prevalence is an important issue in family practice that deserves more scientific research.[Citation19]

T2DM and cancer in general share many common risk factors, but the exact biological relationship between these two diseases is not fully explained. Glycaemic control in cancer patients is often sub-optimal; however, it is not dependent on cancer type. Our finding that among all cancer types solely breast cancer is positively associated with elevated HbA1c is important, since chronic hyperglycaemia is associated with a significantly higher risk of all-cause mortality in breast cancer survivors.[Citation20–22]

In opposition to our finding is that glycaemic control among Spanish patients with type 2 diabetes was independent of body mass index, and was only associated with abnormal lipid levels.[Citation23] The complex interplay of T2DM, obesity, and dyslipidaemia is associated with increased risk for ischaemic heart disease. Lowering HbA1c decreases the absolute risk of developing coronary heart disease as well as all-cause mortality.[Citation24]

In Croatia, care of patients with T2DM has been recently transferred from diabetologists to GPs. Patients with chronic somatic diseases, older patients, and those with more medical problems tend to have more consultations.[Citation25] Comorbidity may increase as well as decrease the chance of treatment intensification in insufficiently controlled patients.[Citation26,Citation27] As the number of comorbidities increases, a “fragmentation” of treating the same patient by different specialists, institutions, and with different treatments increases too. Our result that patients with more comorbidities were less likely to have increased HbA1c is in line with the central role of family physicians or general practitioners, which is to coordinate care with other specialists and to master effective and appropriate care provision and health service utilisation in the management of such patients. In Croatian family practices patients with diabetes receive more procedures for an encounter than they have reasons for (2.6 vs. 2.1).[Citation28] Such control of diabetic patients probably explains their well-achieved control. Also, our result refutes the thesis that GPs, possibly due to the limited time they can devote to a single patient (67 patients examined daily) and many requirements they face, are unable to intervene in proper treatment of T2DM patients with comorbidities.

Our finding of 58.8% of participants having HbA1c above the recommended > 7.0% can also suggest the need for different strategies addressing hyperglycaemic patients. Continuous education of primary care physicians is one way of improving skills to manage hyperglycaemic patients. But the real challenge in treating T2DM patients with the rising prevalence of comorbidity in primary care is to shift the main criterion from a disease-orientated to a person-centred approach in the context of patients’ circumstances.

Also, such a large number of different comorbidities may indicate the additional importance of primary care, as the primary care physician is the only one with a comprehensive picture of the patient. The negative association of physicians’ inertia with the number of comorbidities in our study suggests a lasting presence of comprehensiveness in primary care in Croatia.

Limitations of our study include the cross-sectional design, which does not permit us to draw causal conclusions. We have not controlled the design effect of our multistage sampling. Therefore we probably somewhat overestimated the presented effects. Also, a potential selection bias must be taken into account since the GPs’ participation was voluntary, and their inclusion of patients and the quality or comprehensiveness of chronic condition coding could not be checked. Another potential limitation of this study is that we did not assess the patients’ socioeconomic status and the duration of the doctor–patient relationship, which could partly explain the high prevalence of comorbidity observed. Conducting identical research in primary care in other countries could give external validity to this study.

By taking into account all comorbidities this study adds to the current body of knowledge, since the existing literature studying the effect of comorbidity on diabetes care is predominantly focused on a single coexisting condition. Comorbidity as a common feature of most T2DM patients makes a compelling case for more research into a comprehensive approach by the primary care physician when dealing with this complex issue.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all who participated in the study.

Funding

Association of Teachers in General Practice/Family Medicine (ATGP/FM) in Croatia.

Ethical approval

The Medical Ethics Committee of the Medical School, University of Zagreb, approved the protocol of the study and all participants gave informed consent.

Disclosure statement

There are no financial or other conflicts of interest.

References

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes –2013 position statement. Diabetes Care. 2013;Suppl1:S11–S66.

- Croatian Guidelines on Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Croatian Association for Diabetes and Metabolic Disorders. Available at http://cro-endo.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/HR-smjernice-SBT2-Medix_Medilab-2011-k1.pdf (accessed 15 February 2014).

- Campbell RK. Type 2 diabetes: Where we are today: An overview of disease burden, current treatments, and treatment strategies. J Am Pharmacists Assoc. 2009;49(Suppl 1):S3–S9.

- Feinstein AR: The pre-therapeutic classification of co-morbidity in chronic disease. J Chron Dis. 1970;23:455–468.

- Uijen AA, van de Lisdonk EH. Multimorbidity in primary care: Prevalence and trend over the last 20 years. Eur J Gen Pract. 2008;14(Suppl):28–32.

- Druss BG, Marcus SC, Olfson M, et al. Comparing the national economic burden of five chronic conditions. Health Aff. 2001;20:233–241.

- Wolff JL, Starfield B, Anderson G. Prevalence, expenditures, and complications of multiple chronic conditions in the elderly. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2269–2276.

- Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. American Diabetes Association (ADA); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: A patient‐centered approach: Position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1364–1379.

- Kerr EA, Heisler M, Krein SL, et al. Beyond comorbidity counts: How do comorbidity type and severity influence diabetes patients’ treatment priorities and self-management? J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1600–1640.

- LeChauncy D. Woodard, Urech T, Landrum CR, et al. The impact of comorbidity type on measures of quality for diabetes care. Med Care. 2011;49: 605–610.

- Meduru P, Helmer D, Rajan M, et al. Chronic illness with complexity: Implications for performance measurement of optimal glycemic control J Gen Intern Med. 22(Suppl 3):408–418.

- Lash TL, Mor V, Wieland D, et al. Methodology, design, and analytic techniques to address measurement of comorbid disease. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:281–285.

- Van den Akker M, Buntinx F, Metsemakers JF, et al. Multimorbidity in general practice: Prevalence, incidence, and determinants of co-occurring chronic and recurrent diseases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:367–375.

- Croatian Institute of Health Insurance. Guide to the family physicians contracting. http://www.cezih.hr/dokumenti/HZZO_Vodic_kroz_ponudu_NM_za_OM_v19012013.pdf. (accessed 22 Jul 2014).

- Croatian National Institute of Public Health. Croatian health service yearbook 2007. Web edn. Available at: http://hzjz.hr/wp–content/uploads/2013/11/Ljetopis_2007.pdf (accessed 22 July 2014).

- Teljeur C, Smith SM, Paul G, et al. Multimsorbidity in a cohort of patients with type 2 diabetes. Eur J Gen Pract. 2013;19:17–22.

- Pentakota PM, Rajan M, Fincke BG, et al. Does diabetes care differ by type of chronic comorbidity? Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1285–1292.

- Republic of Croatia – Central Bureau of Statistics. Population by sex and age, by settlements, Census 2011 [cited Aug 04, 2014]. Available from: http://www.dzs.hr/Hrv/censuses/census2011/results/htm/H01_01_01/H01_01_01.html

- Fortin M, Lapointe L, Hudon C, Vanasse A. Multimorbidity is common to family practice: Is it commonly researched? Can Fam Physician. 2005,51:244–245.

- Giovannucci E, Harlan DM, Archer MC, et al. Diabetes and cancer: A consensus report. Diab Care. 2010;33:1674–1685.

- Karlin NJ, Dueck AC, Cook CB. Cancer with diabetes: Prevalence, metabolic control, and survival in an academic oncology practice. Endocr Pract. 2012;18:898–905.

- Erickson K, Patterson RE, Flatt SW, et al. Clinically defined type 2 diabetes mellitus and prognosis in early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;29:54–60.

- Vázquez LA, Rodríguez A, Salvador J, et al. Relationships between obesity, glycemic control, and cardiovascular risk factors: A pooled analysis of cross-sectional data from Spanish patients with type 2 diabetes in the preinsulin stage. BMC Cardiovasc Disorders. 2014;14:153.

- Ten Brinke R, Dekker N, de Groot M, Ikkersheim D. Lowering HbA1c in type 2 diabetics results in reduced risk of coronary heart disease and all-cause mortality. Prim Care Diabetes. 2008;2:45–49.

- Smits FThM, Brouwer HJ, ter Riet G, HCP van Weert. Epidemiology of frequent attenders: A 3-year historic cohort study comparing attendance, morbidity and prescriptions of one-year and persistent frequent attenders. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:36.

- Higashi T, Wenger NS, Adams JL, et al. Relationship between number of medical conditions and quality of care. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2496–2504.

- Vitry AI, Roughead EE, Preiss AK, et al. Influence of comorbidities on therapeutic progression of diabetes treatment in Australian veterans: A cohort study. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14024.

- Vrca Botica M, Zelic I, Pavlic Renar I, et al. Structure of visits persons with diabetes in Croatian family practice: Analysis of reasons for encounter and treatment procedures using the ICPC-2. Coll Antropol. 2006;3:495–499.