Abstract

Objective: To identify factors that hinder discussions regarding chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) between primary care physicians (PCPs) and their patients in Sweden. Setting: Primary health care centres (PHCCs) in Stockholm, Sweden. Subjects: A total of 59 PCPs. Design: Semi-structured individual and focus-group interviews between 2012 and 2014. Data were analysed inspired by grounded theory methods (GTM). Results: Time-pressured patient–doctor consultations lead to deprioritization of COPD. During unscheduled visits, deprioritization resulted from focusing only on acute health concerns, while during routine care visits, COPD was deprioritized in multi-morbid patients. The reasons PCPs gave for deprioritizing COPD are: “Not becoming aware of COPD”, “Not becoming concerned due to clinical features”, “Insufficient local routines for COPD care”, “Negative personal attitudes and views about COPD”, “Managing diagnoses one at a time”, and “Perceiving a patient’s motivation as low’’. Conclusions: De-prioritization of COPD was discovered during PCP consultations and several factors were identified associated with time constraints and multi-morbidity. A holistic consultation approach is suggested, plus extended consultation time for multi-morbid patients, and better documentation and local routines.

Under-diagnosis and insufficient management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are common in primary health care. A patient–doctor consultation offers a key opportunity to identify and provide COPD care.

Time pressure, due to either high number of patients or multi-morbidity, leads to omission or deprioritization of COPD during consultation.

Deprioritization occurs due to lack of awareness, concern, and local routines, negative personal views, non-holistic consultation approach, and low patient motivation.

Better local routines, extended consultation time, and a holistic approach are needed when managing multi-morbid patients with COPD.

Key points

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a common and often undiagnosed cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide.[Citation1] The prevalence of physiologically defined COPD in adults older than 40 years is approximately 9–10%.[Citation2] The disease causes extensive suffering and adds substantial burden to national healthcare budgets, not least due to acute hospital admissions and years of disability.[Citation3] Smoking cessation is the most effective intervention, while medication can ease the symptoms and prevent exacerbations.[Citation4] An early diagnosis is important: it may motivate the patient to quit smoking, which is the only measure known to radically improve future prospects for the patient.[Citation5]

Under-diagnosis and insufficient management of COPD and its comorbidities are still common in primary health care, despite increased awareness of the disease among patients as well as primary care physicians (PCPs) and despite current diagnostic guidelines.[Citation6–8] To narrow the gap between theory and practice, more studies are needed on the implementation of COPD guidelines in primary care practice.[Citation9]

Identifying barriers to implementation of guidelines is necessary for targeted interventions.[Citation10] Previous primary care research on COPD has indicated that PCPs generally experience conflicts between current guidelines and a patient’s individual needs. Thus, there have been suggestions regarding the development of guidelines tailored to the needs of primary health care.[Citation11,Citation12] Factors that affect PCPs’ adherence to guidelines for COPD have, to date, mainly been studied using surveys. The results from such surveys indicated low familiarity with current guidelines, difficulties in interpreting spirometry, time constraints, and therapeutic nihilism as possible factors behind poor implementation of COPD guidelines.[Citation13,Citation14]

Therefore, the aim of the study was to describe factors that hinder discussions concerning COPD between primary care physicians (PCPs) and their patients in Sweden. Results from this study could help achieve a deeper understanding of the barriers to providing high-quality care to patients with COPD.

Material and methods

A qualitative research method inspired by the grounded theory method (GTM), developed by Glaser and Strauss [Citation15–18] as outlined in Hylander [Citation18] and Charmaz,[Citation17] was used to define and understand the underlying factors behind PCPs’ omission and deprioritizing of COPD. GTM is commonly used to generate a conceptual understanding (theory) from a bottom-up analysis of textual data.[Citation15,Citation16]

Settings and participants

In this study, data were collected through focus-group and individual interviews. Fifty-nine PCPs were recruited from 11 primary health care centres (PHCCs) in Stockholm, Sweden between 2012 and 2014.

Primary health care in Sweden

In Sweden, almost all primary care physicians (PCPs) are employed by primary health care centres (PHCC), which are run by the county councils, either directly or by contracting private companies. According to the policies of county councils, all PHCCs must provide the general population with certain primary care services that are carried out by PCPs and district nurses. Primary care rehabilitation units are often independently organized and managed separately from PHCCs. The remuneration system, accessibility to rehabilitation and secondary care units, local care traditions (for example, specialized nurse-led appointments for diabetes or COPD), and guidelines are examples of factors that influence working conditions for PCPs.

The Swedish PCPs tend to see fewer patients a day compared with many other countries due to a general tradition of managing multiple health issues during one consultation, which often can take up to 30 minutes. Ideally, each patient has an assigned PCP with whom he/she has consultations. However, a shortage of family physicians in Sweden results in employing many substitute physicians on short-term contracts, which, in turn, leads to discontinuity in the patient–doctor relationship.

In principle, there are two types of patient visits: (1) regular scheduled, routine care visits, which typically aim to investigate non-acute health issues. These include check-ups for chronic illnesses that take 20–30 minutes and often occur once or twice a year per patient; (2) urgent, unscheduled visits for acute health problems, which are more common, though shorter in duration, and patients are treated by the physician on call, i.e. they often do not get to see their assigned PCP.

Practically all employers in Sweden offer PCPs regular (monthly or weekly) continuing medical education (CME), which is given either by the authorities, non-profit organizations, or the pharmaceutical industry.

Selection of participants

The selection of participants was conducted as a theoretical sampling in accordance with GTM,[Citation15] i.e. data were collected continuously and in parallel with data analyses. As rich data is an essential element in GTM, we intentionally, and pragmatically, selected the PHCCs and PCPs to achieve high heterogeneity. The PHCCs were located in urban or suburban, but not rural, areas of Stockholm with a variety of different demographic and socio-economic characteristics, as well as number of patients. Also, PHCCs both with and without a nurse-led asthma/COPD clinic were included. Participating PCPs worked both at ordinary PHCCs during office hours and at local emergency units after hours. Initially, 10 PHCCs were contacted by email, of which five agreed to participate in focus-group interviews. These groups and the participants in them were contacted one by one as the study proceeded, to fill in the gaps in the data. An example of theoretical sampling was including PCPs working in PHCCs that were located centrally as the analysis indicated that city-based PHCCs in geographic closeness to a hospital could affect how PCPs managed COPD.

All participants received information regarding the study prior to recruitment and only those with their manager’s formal permission to participate were included. In addition, only PCPs who were qualified specialists in family medicine (or close to being qualified) and had a permanent employment contract were included, thus minimizing bias from short-term employees.

Initially, five focus-group interviews (A–E) with four to 10 PCPs in each interview, were conducted by the first author (HS). The interviews were scheduled to coincide with the physicians’ ordinary, non-sponsored session for CME to minimize the risk of including data only from participants with a special interest in COPD. To conclude the data collection, as described in the interview guides (see ), four more individual interviews (F–I) and two focus-group interviews with seven and five participants (J–K) respectively were conducted by HS. The characteristics of all the participants are given in .

Table 1. Characteristics of the primary care physicians (PCPs) who participated in the interviews concerning discussions about COPD in patient consultations (n = 59).

Table 2. The gradually developed interview guides in chronologic order (I–VI) for the semi-structured interviews (A–K) for exploring the factors that influence PCPs’ level of prioritizing of COPD in a consultation.

Constant parallel data collection and comparative analysis

The average duration of the interviews was 37 minutes (ranging from 23 to 55 minutes). The smaller the number of participants in the interviews or the farther along the interview came in the data-collection process, the shorter the duration of the interview. The latter was mainly due to theoretical sampling of data, in which the themes on the interview guides were gradually narrowed down.

In accordance with GTM, an initial interview guide with open questions was created. A semi-structured interview technique was used where open questions were followed by specific questions. To find answers to the main background question, “Why are the COPD guidelines not followed?”, the participants were asked to discuss the different clinical situations that would cover the areas of interest. These situations are outlined in the initial interview guide seen in . Examples of open questions regarding clinical situations of interest were “What makes you suspect COPD in a patient you meet?”, or, “Tell us about the latest COPD patient you met”, followed by specific questions, such as “Why did you choose to do that with your patient?”. The interviewer would then engage the rest of the group by asking, “What do the others think of this? How would you have acted in a situation like this?”. The open discussion encouraged the participants to share their opinions, standpoints, and experiences with each other, which led to follow-up questions. In accordance with GTM, the interview guide would gradually be developed to go deeper into new or unresolved issues, as shown in . The interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim.

Data collection and analysis were conducted in parallel. A transcribed interview with the text in Swedish was analysed by coding and categorizing the data prior to the next interview, which determined the direction of the follow-up questions, further data collection, and analysis.

Data analysis was performed using open, focused, and theoretical coding (constant comparison method). In open coding every sentence was analysed line by line to determine its meaning so as to generate substantial but rudimentary labels; for example, “You really don’t expect adherence to treatment from someone who has smoked himself to COPD” was coded as “PCPs’ views on COPD”. Focused coding involved a deductive analysis of preliminary categories, leading to categories such as “Low status of COPD among chronic diseases”. Finally, in theoretical coding, more conceptual categories were created, such as “Negative personal views and attitudes regarding COPD” and the relationships between categories were analysed. This step-by-step coding method gave rise to new interview questions. When categories were deemed saturated and when no more new categories or connections between categories were found, a theoretical model to address the main research question emerged to illustrate the core process.

The initial coding of each interview was carried out by HS. The analysis was then further discussed whereby the themes, categories, and additional interview questions were agreed upon between the authors (HS, IH, SM, and AN), of whom two have extensive experience and knowledge in GTM. In addition, inter-professional discussions and academic presentations were carried out during the process of data analysis to gain further support and receive feedback.

Results

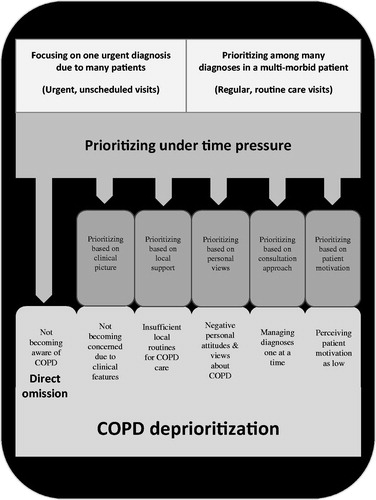

The main concern of the 59 interviewed PCPs from 11 PHCCs is their “difficulty to prioritize COPD in the limited time available”, i.e. PCPs prioritize either one urgent medical issue or one out of many diagnoses in a multi-morbid patient, thus neglecting detection and long-term management of COPD. Hence, the core process Prioritizing under time pressure leads to Deprioritization of COPD. The theoretical model explaining the process of omission or deprioritization of COPD at a patient–doctor encounter is shown in . Omission or prioritizing depends on six factors, i.e. main categories: (1) awareness of COPD, (2) clinical picture, (3) local support, (4) personal views, (5) consultation approach (managing diagnoses one at a time or using a holistic consultation approach), and (6) patient motivation. Each main category includes aspects that explain the process of omission or deprioritization of COPD. Each main category is described below, including examples of quotations.

Figure 1. The theoretical model describing the process of deprioritization of COPD in a primary care patient–doctor consultation.

Prioritizing under time pressure when meeting COPD patients

“Time pressure” is identified as an immediate consequence of the working conditions at the time of consultation. Urgent visits occur both at the PCP’s regular PHCC and at local emergency units. PCPs experience time pressure when they encounter either many patients with one urgent medical issue (urgent, unscheduled visits), or one patient with many medical issues, i.e. multi-morbidity (regular, routine care visits):

The consultation time is limited and there might be something else of a higher priority that needs to be taken care of sooner. (G)

Besides time pressure, the unscheduled visits are characterized by poor prior knowledge of the patients’ medical history:

You have to keep up the pace. You don’t have time to think. (F)

If you have 20 more sitting in the waiting room, coughing …. It’s like, “Come back if it doesn’t get better!” (B2)

During regular, routine care scheduled visits, patients present with either considerable multi-morbidity or COPD comorbidity. Again, the PCPs report frustration due to time constraints:

I feel there’s not enough time. COPD is rarely the only reason for the visit, it is a secondary reason. (E9)

Regular check-ups for COPD only are considered as rare:

They have multiple conditions. They never come only for COPD. I can count on one hand those who only have COPD. (G)

Thus, there is always time pressure during COPD patient visits, which leads to the main concern: “Difficult to prioritize COPD in the limited time available”.

Awareness of COPD

Not becoming aware of COPD leads to direct omission. If COPD is not documented in the medical record or mentioned by the patient, or if another issue is referred to as the reason for the visit, COPD is likely to be omitted, even though a patient may be at risk of COPD or presents with clinical findings of airway dysfunction:

But if the diagnosis isn’t there – even if I see the patient being a bit breathless when she comes with her walker – I might still forget it. There are so many other things to talk about. (F)

During urgent, unscheduled visits, patient history can give PCPs information on whether the patient has COPD or is at risk of developing the disease, which would affect the choice of future therapy and follow-up, but this is not likely to happen if COPD is not mentioned. Likewise, the complexity of handling multi-morbidity under time pressure contributes to omission of COPD, if it is not mentioned.

Prioritizing based on clinical picture

When PCPs do not become concerned due to clinical features COPD is deprioritized. Possible COPD in younger and middle-aged patients, smokers, and those with mild or moderate symptoms is, in general, not discussed.

If COPD hasn’t been troubling the patient in any special way throughout the years, I tend to forget about it. (G)

It depends on how bad it looks. I mean, if you suspect a mild COPD, then there’s no hurry. (A5)

By contrast, for possible COPD in older smokers with frequent respiratory infections and signs of severe airway obstruction, COPD is typically discussed. The overall assessment of the clinical picture influences decisions, therapy, and follow-up. Lack of concern about COPD leads to lack of action and provision of therapy.

Prioritizing based on local support

If the local routines for COPD care are insufficient, COPD is deprioritized. Routines on structured COPD care based on current guidelines, special nurse-led COPD appointments at the PHCC, and easy access to pulmonary rehabilitation are examples of local support that increases PCPs’ competence and commitment, and encourages them to include COPD in the discussion agenda. Thus local support or “local culture” is often the determining factor for prioritizing of COPD. Without local support COPD is likely to be deprioritized:

Management and activity depends on accessibility of investigation facilities and reliability of the spirometries. If that’s the case [at your health care centre] then you are willing to proceed. Otherwise, it’s such a huge project, with referrals everywhere. (K5)

Prioritizing based on personal views

Deprioritization of COPD is affected by negative personal attitudes and views concerning the disease. Clearly, the PCPs hold different personal opinions of different diseases. Some PCPs are critical about smoking and thus consider COPD as a self-inflicted disease and an unpleasant issue to talk about. Negative personal views of COPD may lead to placing a lower priority on COPD when compared with other diseases or COPD comorbidities, such as heart disease and diabetes:

If you are thinking “dyspnoea” you need to make a rough assessment of whether you think it is the heart or the lung. You might then choose the heart before the lung. (B2)

I’m pretty sure we take care of patients with diabetes a bit better. Although I can’t say why. It is a bit more accepted disease. (B3)

In addition, a feeling of helplessness regarding treatment and low expectations of a patient’s adherence to treatment lead to deprioritization:

Why isn’t COPD managed by the recommendations? Because it has such a low status. No one wants to mention it. It is boring to even say the name of the disease.… You really don’t expect adherence to treatment from someone who has smoked himself to COPD. That’s probably why you don’t refer or treat them. (A2)

This may raise the question of whether to inform or protect the patient from this “bad diagnosis”:

Does this woman who has quit smoking have any use in knowing it is COPD? I mean, she has chronic symptoms, but why give her a chronic diagnosis that is just bad news. Has she any use for it? Has she any use for having that sticker on her? (I)

In contrast, PCPs who have a neutral or a positive attitude towards COPD and, thus, consider it just as important as other lifestyle-associated chronic diseases, sympathize with the patients and firmly believe that the patients should receive help:

I have seen so many other types of patients who live miserable lives, either self-inflicted or because of other things…. I mean, I’m not the police here! (I)

Prioritizing based on consultation approach

Managing diagnoses one at a time rather than altogether by a holistic consultation approach leads to near lack of action and deprioritization of COPD, especially when coupled with PCPs’ negative views about COPD:

I always feel there are so many issues! And there are more and more things coming up all the time…. Sleeping problems, a skin problem, and…. It is the GP’s job! Classic! And then I feel I need to exclude COPD. (H)

In the case of multi-morbidity, unless airway symptoms are clearly prominent, PCPs usually run out of consultation time before COPD is even mentioned. Lack of objective measurements, i.e. laboratory tests, can lead to difficulties in monitoring COPD or having discussions about it:

What the hell can you check? You’ve given them medicines with modest effects … what should I look for? (C3)

By using an approach where the diagnoses are managed one at a time the PCP reduces his/her workload simply by ignoring COPD:

The down side is that it increases my workload.… Instead of discussing smoking, referring to spirometry and planning for follow-up, I just write a prescription for antibiotics. Thank you, and goodbye! It goes much faster. (E1)

On the other hand, PCPs who use a holistic consultation approach include COPD in the discussion. Open questions encourage the patient to take part in the discussion. This way, PCPs can form a broad picture of a patient’s well-being, symptoms, and core concerns and, consequently, this may lead to relevant discussions about COPD.

I usually bring up [COPD] from the context of what the patient feels, what he experiences. They usually don’t think, “I have COPD”.… So I try to put the symptoms and the diseases into a context that I can explain to the patient. (H)

In the case of an urgent visit, PCPs may get the opportunity to detect COPD early.

Prioritizing based on patient motivation

Perceiving the patient’s motivation as low is an important aspect of COPD deprioritization. Irrespective of the type of consultation approach, most PCPs nowadays use a patient-centred approach, which is wrongly regarded by some as an approach whereby it is the patient only who decides what is to be discussed. PCPs feel that the patient’s agenda reflects the patient’s level of motivation to receive COPD care, hence determining the course of the discussion during consultation. According to the PCPs, patients rarely initiate discussions about COPD due to lack of motivation for smoking cessation or other treatment options, because they find other health issues more important or because they seem content with their respiratory health:

Most of the times it is the patient who decides. I don’t think it is us doctors who prioritize it. The patient has his questions, and no matter if it’s supposed to be a check-up for hypertension or heart failure, the patient might want to discuss something completely different, anyway. And we need to let them do that. We cannot be robots who force them into a form. (C7)

The patients are often perceived as having a bad conscience and feel guilty for having COPD:

They rarely bring it up, actively. I think many of them have a bad conscience. They harbour their own anxiety. (E1)

There’s a lot of guilt, I would think. (E8)

However, if patients show interest or worry regarding a severe airway disease, like lung cancer or COPD, they are perceived as motivated and consequently COPD is discussed during a consultation:

I am more active when the patient comes to me because of his symptoms, not just because I think I see symptoms. (I)

Discussion

Statement of principal findings

In this qualitative study of 59 PCPs from various PHCCs in Stockholm, we found that PCPs who work under time pressure find it difficult to prioritize COPD in the limited time available. We developed a theoretical model that shows how time pressure leads to omission or deprioritization of COPD during consultation in primary health care. The model describes six main categories to explain omission or deprioritizing of COPD. In our model, direct omission of COPD is a consequence of not becoming aware of the diagnosis. Deprioritization is due to not becoming concerned about the clinical picture of COPD, insufficient local routines for COPD care, the PCP’s negative personal views about COPD, consultation approach (managing diagnoses one at a time instead of a holistic consultation approach), or low perceived motivation on the patient’s part.

Strengths and weaknesses

The use of GTM strengthens this study as it allows the systematic analysis of raw data and reduces the influence of preconceptions in questionnaires and surveys. The results are well grounded due to collecting data via both individual and focus-group interviews. The quality of the interviews was considered sufficient due to an appropriate balance between adherence and freedom in terms of following the interview guides. The guides had a “red line” throughout their development process, and consisted of constructive, open questions with detailed answers. However, there may be bias in this study introduced by interviewing established groups of participants, hence small variations in the answers due to personal familiarity and existing hierarchies, rather than randomly selected ones. We tried to minimize the bias by ensuring that all participants received the same information prior the interviews. In addition, the relatively large number of focus groups in this study may, in part, have minimized the bias. Also, as the interviewed PCPs openly talked about not following the guidelines, the existing hierarchies within the focus groups were not considered to have a dominant significance. As the results clearly revealed negative attitudes and passiveness towards COPD, we can assume the groups did not only consist of PCPs with a special interest in COPD.

The data were processed continuously by comparative analysis. Undue and unintended bias and preconceptions from the highly experienced researchers was minimized by inter-professional discussions and academic presentations. The final analysis was carried out mainly by four of the six authors, namely three PCPs and a researcher with long experience in GTM. The fairly high number of participants in our study, all with a well-defined profession and uniform working conditions, could render our model applicable to other similar contexts given that appropriate adjustments are made. It is worth pointing out that, though well grounded in data, GT can never be transferred to a new context without trying the fit in that particular context.

By having included rural and/or insufficiently staffed PHCCs, we may have potentially identified additional factors that affect COPD management in Sweden, though this needs to be studied separately.

Findings in relation to previously published work

The Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF), an overarching theoretical framework on behaviour change in health care professionals, has been developed to provide a conceptual basis for exploring problems, designing interventions, and understanding behaviour-change processes in the implementation of evidence-based care.[Citation19] The six categories in our theoretical model are consistent with some of TDF’s key 12 domains for behaviour change, namely “Beliefs about Capabilities”, “Beliefs about Consequences”, “Motivation and Goals”, “Environmental Context and Resources”, and “Emotion”. However, the domains expressing physicians’ knowledge, skills, memory, and attention were not considered as major factors in our study. On the other hand, Organizational Readiness for Change (ORC), another well-known and key theoretical concept in implementation processes, is clearly supported by our findings. ORC is used to express and assess the collective motivation of the members of an organization as well as their capability to implement change. Our results highlight the importance of locally organized COPD care in prioritizing COPD, preferably within the same PHCC. Examples of such care include nurse-led COPD clinics and pulmonary rehabilitation units.[Citation20]

Previous survey studies have shown that time constraints were one of the main reasons for poor adherence to COPD guidelines.[Citation13] Our study not only confirmed this but, due to our qualitative approach, also added a new dimension to the research question: Is COPD discussed at all during consultation?

An obvious prerequisite for discussing COPD is to become aware of the disease. The absence of typical clinical features adds on to omission or deprioritization of COPD. “Patient’s delay” has been mentioned in earlier research into adaptation to symptoms, lack of awareness, and a feeling of being “not worthy”.[Citation21,Citation22] To avoid delays in COPD detection, PCPs should pay close attention to middle-aged patients, smokers, and patients with respiratory infections.[Citation23] They should also be vigilant about common non-airway symptoms, possibly originating from COPD comorbidities, such as heart disease, pain disorders, depression, and weight problems. A routine use of validated questionnaires such as the COPD Assessment Test (CAT) [Citation24] and the Clinical COPD Questionnaire (CCQ) [Citation25,Citation26] should be encouraged for monitoring the disease.

Lacking local support, such as specialized nurse-led appointments and local guidelines, leads to deprioritization of COPD. Previous research has shown that locally organized interdisciplinary care contributes to easily accessed and cost-effective quality care for COPD patients.[Citation27] Recent Swedish studies have shown improvements in COPD care at PHCCs with nurse-led COPD appointments, not least due to increased level of guideline adherence by PCPs.[Citation28] Difficulties with interpretation of the spirometry results have previously been suggested as an obstacle for active COPD care.[Citation13,Citation14] Interestingly, this aspect was not even mentioned by the interviewed PCPs as a reason for deprioritization of COPD.

Johnson et al. have previously described how negative attitudes towards COPD correlate linearly to fewer referrals for pulmonary rehabilitation.[Citation29] Similarly, our study suggests that negative attitudes, due to frustration over non-effective COPD medications and failure to convince patients to quit smoking, hinder discussions about COPD. A recent French study revealed that many PCPs consider COPD as “boring”, which hampers their management of the disease.[Citation30] Our study indicates that, in Sweden, there are differences in PCPs’ attitudes towards lifestyle choices, such as smoking. This is an example of deeply rooted personal views that may be difficult to change.[Citation31]

In a recent Norwegian study, an average of three problems were presented in a non-urgent patient consultation in primary care.[Citation32] At the same time, research indicates that PCPs find it challenging to establish a good dialogue and prioritize multiple diagnoses within the timeframe of a normal consultation.[Citation33] By managing diagnoses one at a time many PCPs deprioritize COPD and then fail to recognize the impact of COPD on patients’ health.[Citation34] With its many comorbidities [Citation7] and a multifold impact on both patients and their families,[Citation35] COPD may be better managed by using a holistic approach.[Citation36] The latter concerns the very definition of general practice: the importance of a multi-faceted approach to improve health and manage illness.[Citation37]

Prioritizing based on patient motivation is the most critical factor behind deprioritizing COPD. Previous research has shown that many patients with COPD develop pressure-filled mental states such as feeling fearful, criticized, pressured, and not worthy when trying to quit smoking or when refusing pulmonary rehabilitation.[Citation22,Citation38] Bearing in mind that patients with COPD often feel ashamed and experience stigmatization due to society’s view of COPD as a self-inflicted disease,[Citation39,Citation40] it is important for health professionals to pay close attention to how they communicate COPD and smoking cessation to patients. The “patient-centred approach” has been proposed to include six dimensions: exploring both the disease and the illness experience, understanding the person as a whole, finding common ground, incorporating prevention and health promotion, enhancing the patient–doctor relationship, and being realistic.[Citation41] This communication approach has previously been shown to increase the chances of providing satisfactory care,[Citation42] hence, it has become a natural model for an optimal consultation in modern health care. However, our results indicate that PCPs may have misinterpreted the principles of the “patient-centred approach” to the extent where the patient’s agenda dominates during a consultation and the PCP’s medical assessment is not given priority – in other words, the PCPs may have resigned from their role as an expert in COPD. To actively communicate COPD is especially important as patients may tend to avoid bringing up COPD due to shame, guilt, and a low motivation for receiving COPD care. Additionally, lack of initiative on the part of a physician may result in negative long-term consequences for patients with underlying COPD. By taking a non-judgemental standpoint to smoking, PCPs may help decrease the stigma and increase the patient’s motivation to receive treatment for COPD.[Citation43]

Meaning of the study

The results of our study may contribute to a constructive dialogue between policy-makers and medical professionals, as a strong organization and sufficient financing are prerequisites for high-quality and cost-effective management of chronic, multi-morbid conditions like COPD.[Citation44]

The current clinical guidelines for single diseases tend to favour polypharmacy and offer no guidance on prioritizing recommendations for multi-morbid patients.[Citation45] By improving PCPs’ and medical students’ understanding of the impact of COPD in a multi-morbid patient, a holistic treatment approach tailored to the needs of individual patients could be possible. The results of our study have been integrated in an educational programme for Swedish PCPs. The programme focuses on multi- and comorbidity, holistic consultation, local routines, and patient motivation. We will assess its impact on both patients and PCPs.

Conclusion

We discovered deprioritization of COPD during PCP consultations and identified several factors associated with time constraints and multi-morbidity. We suggest a holistic consultation approach, extended consultation time for multi-morbid patients and better documentation and local routines.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Scientific Editor Stella Papadopoulou for language improvements throughout this article.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board of Stockholm (ref 2011/731-31/1). Written consent was obtained for all PCPs and their managers.

Disclosure statement

HS has received honoraria for educational activities from Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, and AstraZeneca and an unrestricted research grant from AstraZeneca. AN has received compensation for educational activities from AstraZeneca. BS has received honoraria for educational activities and lectures from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Meda, MSD, Novartis, and TEVA, and has served on advisory boards arranged by AstraZeneca, Novartis, and Boehringer Ingelheim. IH, IK, and SM report no competing interests.

References

- Lopez AD, Shibuya K, Rao C, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: current burden and future projections. Eur Respir J. 2006;27:397–412.

- Halbert RJ, Natoli JL, Gano A, et al. Global burden of COPD: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:523–532.

- Jansson SA, Andersson F, Borg S, et al. Costs of COPD in Sweden according to disease severity. Chest. 2002;122:1994–2002.

- Yang IA, Clarke MS, Sim EH, Fong KM. Inhaled corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;7:CD002991.

- Van Schayck CP, Chavannes NH. Detection of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in primary care. European Respir J. 2003;39:16s–22s.

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; [cited 2015 Jan]. Available from http://www.goldcopd.com/.

- Stallberg B, Janson C, Johansson G, et al. Management, morbidity and mortality of COPD during an 11-year period: an observational retrospective epidemiological register study in Sweden (PATHOS). Prim Care Respir J. 2014;23:38–45.

- Lindberg A, Bjerg A, Ronmark E, et al. Prevalence and underdiagnosis of COPD by disease severity and the attributable fraction of smoking. Report from the Obstructive Lung Disease in Northern Sweden Studies. Respir Med. 2006;100:264–272.

- Pinnock H, Thomas M, Tsiligianni I, et al. The International Primary Care Respiratory Group (IPCRG) Research Needs Statement 2010. Prim Care Respir J. 2010;19(Suppl 1):S1–S20.

- Grol R, Grimshaw J. From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients’ care. Lancet. 2003;362:1225–1230.

- Carlsen B, Glenton C, Pope C. Thou shalt versus thou shalt not: a meta-synthesis of GPs’ attitudes to clinical practice guidelines. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57:971–978.

- Schunemann HJ, Woodhead M, Anzueto A, et al. A vision statement on guideline development for respiratory disease: the example of COPD. Lancet. 2009;373:774–779.

- Perez X, Wisnivesky JP, Lurslurchachai L, et al. Barriers to adherence to COPD guidelines among primary care providers. Respir Med. 2012;106:374–381.

- Yawn BP, Wollan PC. Knowledge and attitudes of family physicians coming to COPD continuing medical education. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2008;3:311–317.

- Glaser BG SA. Grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine;1967.

- Strauss AL CJ. Basics of qualitative research techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 1998.

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory. London and Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 2006.

- Hylander I. Towards a grounded theory of conceptual change process in consultee-centered consultation. J Educ Psychol Cons. 2003;14:263–280.

- Francis JJ, O’Connor D, Curran J. Theories of behaviour change synthesised into a set of theoretical groupings: introducing a thematic series on the theoretical domains framework. Implement Sci. 2012;7:35.

- Weiner BJ. A theory of organizational readiness for change. Implement Sci. 2009;4:67.

- Horie J, Murata S, Hayashi S, et al. Factors that delay COPD detection in the general elderly population. Respir Care. 2011;56:1143–1150.

- Harrison SL, Robertson N, Apps L, M CS, et al. “We are not worthy”: understanding why patients decline pulmonary rehabilitation following an acute exacerbation of COPD. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;10:1–7.

- Sandelowsky H, Stallberg B, Nager A, Hasselstrom J. The prevalence of undiagnosed chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a primary care population with respiratory tract infections: a case finding study. BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12:122.

- Friedman JM, Jones PA. MicroRNAs: critical mediators of differentiation, development and disease. Swiss Med Wkly. 2009;139:466–472.

- Van der Molen T, Willemse BW, Schokker S, et al. Development, validity and responsiveness of the Clinical COPD Questionnaire. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:13.

- Stallberg B, Nokela M, Ehrs PO, et al. Validation of the clinical COPD Questionnaire (CCQ) in primary care. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:26.

- Rumball–Smith J, Wodchis WP, Kone A, et al. Under the same roof: co-location of practitioners within primary care is associated with specialized chronic care management. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15:149.

- Lisspers K, Johansson G, Jansson C, et al. Improvement in COPD management by access to asthma/COPD clinics in primary care: data from the observational PATHOS study. Respir Med. 2014;108:1345–1354.

- Johnston KN, Young M, Grimmer KA, et al. Barriers to, and facilitators for, referral to pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD patients from the perspective of Australian general practitioners: a qualitative study. Prim Care Respir J. 2013;22:319–324.

- Bouchez T, Huas D, Roche N, et al. QUALIEFR: a qualitative study of determinants of early detection of COPD in general practice in France. Conference abstract, International Primary Care Respiratory Group World Conference 2014; [cited 2014 May 22]. Available from http://www.theipcrg.org/pages/viewpage.action?pageId=12386453.

- Wilson TD, Hodges SD. Attitudes as temporary constructions. In: Martin LL, Tesser A, editors. The construction of social judgment. Hillsdale (NJ): Erlbaum; 1992. p. 37-66.

- Bjorland E, Brekke M. What do patients bring up in consultations? An observational study in general practice. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2015;33:206–211.

- Sondergaard E, Willadsen TG, Guassora AD, et al. Problems and challenges in relation to the treatment of patients with multimorbidity: general practitioners’ views and attitudes. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2015;33:121–126.

- Levenstein JH, McCracken EC, McWhinney IR, et al. The patient-centred clinical method, 1: a model for the doctor–patient interaction in family medicine. Fam Pract. 1986;3:24–30.

- Zakrisson AB, Theander K, Anderzen-Carlsson A. The experience of a multidisciplinary programme of pulmonary rehabilitation in primary health care from the next of kin’s perspective: a qualitative study. Prim Care Respir J. 2013;22:459–465.

- Mirzaei M, Aspin C, Essue B, et al. A patient-centred approach to health service delivery: improving health outcomes for people with chronic illness. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:251.

- Van Dormael M. Roles of the general practitioner in different contexts. Ann Soc Belg Med Trop. 1995;75(Suppl 1):79–88.

- Lundh L, Hylander I, Tornkvist L. The process of trying to quit smoking from the perspective of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Scand J Caring Sci. 2012;26:485–493.

- Berger BE, Kapella MC, Larson JL. The experience of stigma in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. West J Nurs Res. 2011;33:916–932.

- Halding AG, Heggdal K, Wahl A. Experiences of self-blame and stigmatisation for self-infliction among individuals living with COPD. Scand J Caring Sci. 2011;25:100–107.

- Stewart M BJ, Weston WW, Freeman TR. Patient-centred medicine: transforming the clinical method. 2nd ed. London: Radcliffe Medical Press; 2003.

- Butow P, Brown R, Aldridge J, et al. Can consultation skills training change doctors’ behaviour to increase involvement of patients in making decisions about standard treatment and clinical trials: a randomized controlled trial. Health Expect. 2014; Jun 30. doi: 10.1111/hex.12229. [Epub ahead of print]

- Roddy E, Antoniak M, Britton J, et al. Barriers and motivators to gaining access to smoking cessation services amongst deprived smokers: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:147.

- Erler A, Bodenheimer T, Baker R, et al. Preparing primary care for the future; Perspectives from the Netherlands, England, and USA. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 2011;105:571–580.

- Hughes LD, McMurdo ME, Guthrie B. Guidelines for people not for diseases: the challenges of applying UK clinical guidelines to people with multimorbidity. Age Ageing. 2013;42:62–69.