Abstract

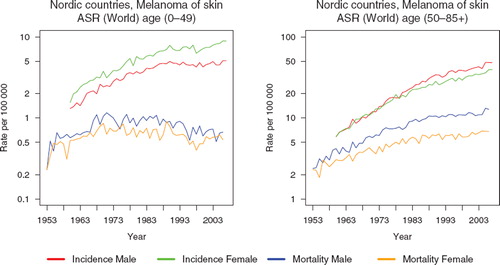

A previous Nordic study showed a marked and steady increase in the age-adjusted 5-year relative survival of skin melanoma patients diagnosed during the period 1958 through 1987. Males had considerably poorer survival than females. Material and methods. Using the NORDCAN database, we studied relative survival and excess mortality of patients diagnosed with melanoma of the skin in the Nordic countries 1964–2003 followed up to the end of 2006. These were contrasted with concomitant trends in incidence and mortality. Results. The overall incidence of melanoma almost quadrupled, but there was considerable variation in the trends in the five countries. Mortality was low but doubled during the study period. Survival ratios increased steadily to between 80% and 90% for patients diagnosed in 1999–2003. Swedish patients had consistently higher survival, whereas Danish patients had the highest excess death rates the first three months after diagnosis up until 1990, but thereafter, rates reached a similar low level to that observed in the other Nordic countries. The survival of Nordic women is still higher than that of men, but the difference has diminished, while the mortality rates among men are becoming increasingly higher relative to those for women among individuals 50 years and older. In younger individuals, mortality rates are similar in the two sexes, and declining. Conclusions. Nordic patient survival following melanoma diagnosis is generally high and has been steadily increasing in the last decades. Differences in incidence between the five countries are more pronounced than the differences in survival. The strong upward trends in incidence and survival may mainly be the result of extensive changes in sunbathing habits or other UV exposure and, more recently, of an increasing awareness by the medical community and the public concerning early detection of melanoma of the skin.

Malignant melanoma of the skin (melanoma) was a rare disease in the Nordic countries 50 years ago, but the incidence has risen dramatically over time, and currently comprises 4% of all cancers in the Nordic countries and almost 2% of all cancer deaths. In 1999–2003, an average of 4 500 incident cancers were diagnosed yearly and nearly 1 000 deaths occurred due to melanoma [Citation1]. The main known environmental risk factor is intermittent exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, but the effects of UV radiation are highly dependent on skin type, and to a certain extent on inherited mutations [Citation2,Citation3]. Higher socioeconomic groups have higher incidence and higher survival ratios than lower socioeconomic groups [Citation4].

The most important prognostic factors for melanoma patients are lymph node involvement and/or metastatic spread as well as the thickness of the lesion. Other important factors are gender, presence or absence of ulceration, age at diagnosis, and the anatomical location of the tumour [Citation5]. The most common location among women is at the extremities, a location that is associated with higher survival ratios than the more typical locations among males, i.e. on the trunk, head and neck. Women have generally higher survival than men, but this cannot be explained entirely by the higher incidence of extremity location, lower stage at diagnosis or other more favorable primary tumour characteristics as compared with men [Citation6–8].

The survival of European melanoma patients is generally high and does not vary greatly. Nordic patients have slightly higher 5-year survival than the European mean, which was 83% in the EUROCARE-4 study [Citation9]. A previous Nordic study showed a marked and steady improvement in the age-standardised 5-year relative survival of patients diagnosed during the period 1958 through 1987, with little variation between the Nordic countries, especially towards the end of the period [Citation10]. The aim of the present study is to describe, compare and interpret the Nordic trends in melanoma with respect to incidence, mortality and relative survival in patients diagnosed between 1964 and 2003, as well as examine excess mortality due to this cancer according to time elapsed from diagnosis.

Material and methods

Melanoma of the skin is here defined as ICD-10 code C43. The data source and methods are described in detail in an earlier article in this issue [Citation11]. In brief, the NORDCAN database contains comparable data on cancer incidence and mortality in the Nordic countries; data are delivered by the national cancer registries, with follow-up information on death or emigration for each cancer patient available up to and including 2006. We calculated sex-specific 5-year relative survival for each of the diagnostic groups in each country for eight 5-year periods from 1964–1968 to 1999–2003. For the last 5-year period, the hybrid method was used. Country-specific population mortality rates were used for calculating the expected survival. Age-standardisation of survival used the weights of the International Cancer Survival Standard (ICSS) cancer patient populations [Citation12]. We present age-standardised (World) incidence and mortality rates, 5-year relative survival, and excess mortality rates for the follow-up periods of within one month, one to three months and two to five years following diagnosis, as well as age-specific 5-year relative survival by country, sex and 5-year period.

Results

Incidence and mortality

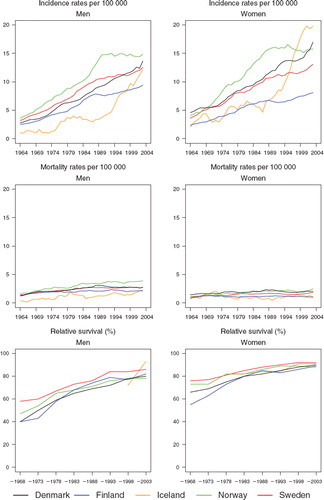

There was great variation in incidence between the five Nordic countries, especially among females. All countries experienced in the 40-year period an almost fourfold increase, resulting in an age-standardised incidence in the period 1999–2003, ranging between 9.0 (per 100 000, Finland) and 14.5 (Norway) among men, and between 7.8 (Finland) and 19.8 (Iceland) among women. The relative increase was similar among men and women. Until the end of the 1980s, Iceland and Finland had the lowest incidence among both sexes, since then however, rapid increases in rates were observed in Iceland (). Norwegian men had the highest incidence rates across the entire period, while Icelandic women surpassed their Norwegian counterparts circa 1997 to exhibit the highest ranked incidence. In Norway, incidence has not increased among either sex since 1990.

Figure 1. Trends in age-standardised (World) incidence and mortality rates per 100 000 and age-standardised (ICSS) 5-year relative survival for malignant melanoma of the skin by sex and country. Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

Mortality was low and more stable over time than incidence. However, there was a doubling of rates during the observation period, with the largest increase in Icelandic and Norwegian men. The mortality was highest among Norwegian men during the entire period, whereas Finnish and Icelandic men had the lowest rates. In 2003 mortality rates ranged from 2.0 (Iceland) to 3.9 (Norway) per 100 000 among men and from 1.0 (Finland) to 2.5 (Norway) per 100 000 among women. Even though incidence was similar in men and women throughout the period, all-ages mortality was higher among men and the sex-specific differences increased steadily with time.

Survival

The relative survival ratios of Nordic patients diagnosed with melanoma were high and have been steadily increasing. For the last period of diagnosis (1999–2003) the survival ratios ranged between 78% and 93% among men and between 88% and 92% in women ( and ). Swedish patients have consistently had the highest survival ratios over calendar time, whereas Finnish and Danish patients have had the lowest survival. Due to the small numbers of Icelandic patients, it was not possible to estimate survival ratios until the most recent years, and these are difficult to interpret given the underlying random variation. Women had higher age-standardised 5-year relative survival ratios than men, but as the ratios among men increased relatively more, the sex-specific differences diminished with time.

Table I. Trends in survival for malignant melanoma of the skin by sex and country. Number of tumours (N) included and the 5-year age-standardised (ICSS) relative survival in percent with 95% confidence intervals (RS (CI)). Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

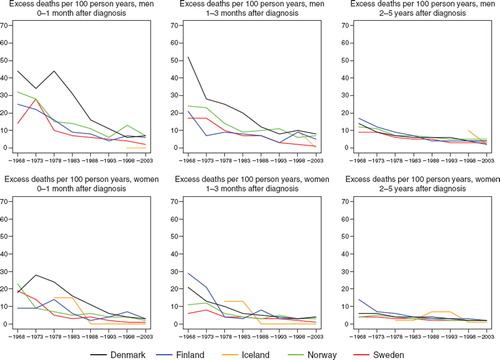

In the earlier periods, Denmark had a much higher excess death rate during the first three month after diagnosis, more notable for men than for women, but in the mid-1990s Denmark reached a level similar to the other Nordic countries (). Sweden and Iceland had the lowest excess mortality during the first three months. The excess death rates became very similar across countries two to five years after diagnosis. Over the entire study period, a reduction in excess death rates during the first three months was observed in all countries, and a reduction was also apparent, albeit to a lesser extent, in the longer term in rates. The excess deaths per 100 person years were consistently higher among men than women,an observation noted soon after diagnosis, and one that was still seen 2-5 years after diagnosis. As shown in the 5-year age-specific relative survival was highest in the youngest group and declined with advancing age in all countries throughout the period, but increase was seen in all age-groups over time.

Figure 2. Trends in age-standardised (ICSS) excess death rates per 100 person years for malignant melanoma of the skin by sex, country, and time since diagnosis in Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

Table II. Trends in 5-year age-specific relative survival in percent after malignant melanoma of the skin by sex and country. Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

In , the incidence and mortality trends (on a logarithmic scale) are shown separately for individuals below age 50 years, and 50 years and older. There have been considerably more pronounced changes in the older group with time, where the incidence in males and females has at least quadrupled and mortality doubled in both sexes. This contrasts with the trends in the younger group; the increase in incidence was threefold in both sexes while the mortality slightly decreased in men and women since circa 1989.

Discussion

In this large population-based study we found that the incidence of malignant melanoma in the Nordic countries almost quadrupled and the mortality doubled between 1964 and 2003, and was highest in Norwegian men. Relative survival improved markedly and is currently between 80% and 90%. It has remained consistently higher in women than men over time, although the differences have diminished.

The survival of melanoma patients has also been increasing for several decades in Australia, the US and in a number of European populations, a finding which has been mainly attributed to the raised public awareness due to educational programmes focusing not only on primary prevention, but also on the importance of skin examination in order to detect potential changes in moles (melanocytic naevi) and bringing them to the attention of doctors or dermatologists. This has led to increased diagnostic activity and earlier diagnosis in those countries [Citation13,Citation14].

Advances in the treatment of malignant cutaneous melanoma are likely to explain a much smaller part of the worldwide increased survival, as no dramatic changes have occurred. The standard treatment consists of a wide local excision, with or without sentinel lymph node biopsy, based on thickness of the lesion [Citation15]. However, a small fraction of the increase may be attributed to advances in treatment, such as sentinel node biopsy and adjuvant treatment [Citation16] and some of the increase may be due to lead time bias occurring when an earlier diagnosis does not affect the timing of death, and length bias which occurs because of an increasing inclusion of indolent cancers that would never have been life threatening [Citation17].

Swedish patients had consistently the highest survival ratios relative to the other Nordic countries during the entire study period. It is likely that an important role is played by the establishment of the Swedish Melanoma Study Group in 1976, which had the objective of creating national guidelines for melanoma diagnosis, treatment and follow-up [Citation18] and also by the establishment of public educational programmes in Sweden [Citation19]. However, the reasons behind the survival also being highest in Sweden before the onset of those programmes are not obvious. The Swedish Cancer Registry does not register death certificate-initiated cases, but it is likely that this could only explain a small amount of the survival differences observed between Sweden and the other Nordic countries, since skin melanoma is rarely seen to be death-certificate initiated in the other Nordic countries.

The excess mortality in Denmark during the first months after diagnosis was well above that of the other countries, most notably among males, until around year 1990; thereafter excess death rates had reached a level similar to the other countries. The excess mortality has declined considerably in all countries during the past 40 years, especially within the first three months following diagnosis.

The most dramatic changes in incidence were observed in Iceland, a geographical area that has a low background UV radiation due to the northern latitude and frequent cloud cover. The increase is most notable from the late-1980s, and among women. This may partly result from a very high prevalence of sun bed use in Iceland, as well as a large increase in travel abroad to southern areas during the past four decades and partly because of increased diagnostic activity due to a nationwide cancer prevention programme which came into action in 1990 [Citation20].

There were only minor differences between the sexes in the overall incidence in the Nordic countries throughout the period, but the mortality was higher among men and the sex-specific differences increased steadily with time. However, this was only seen in diagnoses at ages 50 and older, and the increase in mortality was also confined to this group. In the younger age groups there has been a slight decrease in mortality among both sexes since circa 1989. This favorable development among the young is noteworthy, especially since a relatively high proportion of deaths among melanoma patients occurs under 50 years of age because of a relatively low age at diagnosis. Among Nordic persons who died from melanoma in 1999–2003, about 14% were younger than 50 years (compared to 5% under 50 years when considering deaths from all types of cancer taken together [Citation1]).

Contrasting mortality trends in younger and older age groups have previously been reported from other populations [Citation21,Citation22] and have been attributed to stronger influence on the younger generations of the educational programmes aiming at increased awareness of the precursors of malignant melanoma [Citation21,Citation23, Citation24].

Not enough is known about similar educational programmes in the Nordic countries except for Sweden [Citation19]. However, it is likely that the internationally raised knowledge has also led to increased awareness among health professionals and the public in all the Nordic countries, but probably with considerable variations between countries in extent and timing.

A limitation of this study is the lack of information on stage and thickness of the tumours, as well as the body location. However, we found that the relative proportion of superficial spreading melanomas has been increasing during the study period, although to a different extent within countries (data not shown), which could indicate that the incidence increase may be associated with a relative increase of thin melanomas. The median melanoma thickness decreased significantly in Sweden between 1976 and 1987 [Citation19], and in 1990–1999 [Citation18]. It has been shown that a public education campaign in Scotland in 1985 was followed by a reduction in the absolute number of thick tumours as well as melanoma-related mortality [Citation25].

Increased awareness among both the public and health professionals is likely to be strongly associated with the survival improvements during the past 20–30 years in the Nordic countries, but information is lacking. It is of great importance to study in detail the current status, and if possible to what extent the awareness has changed with time, and compare with the detailed sex- and age-specific changes with time in relative survival, incidence and mortality, according to thickness and body location of the tumours.

It can be concluded that Nordic patient survival following melanoma diagnosis is generally high and has been steadily increasing in the last decades. Differences in incidence between the five countries are more pronounced than the differences in survival. Improved understanding is needed of the forces behind those changes and of the status of the public knowledge about naevi, skin cancer and melanoma in the Nordic countries, in order to be better able to prevent further deaths from malignant melanoma.

Acknowledgements

The Nordic Cancer Union (NCU) has financially supported the development of the NORDCAN database and programme, as well as the survival analyses in this project.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Engholm G, Ferlay J, Christensen N, Bray F, Klint Å, Ólafsdóttir E, . NORDCAN: Cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence in the Nordic countries. Version 3.3. 2008. Available from: http://www.ancr.nu.

- IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. 55. Solar and ultraviolet radiation. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 1992.

- Gruber SB, Armstrong BK. Cutaneous and ocular melanoma. Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni JF Jr. Cancer epidemiology and prevention. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. 1196–229.

- Birch-Johansen F, Hvilsom G, Kjaer T, Storm H. Social inequality and incidence of and survival from malignant melanoma in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994–2003. Eur J Cancer 2008;44:2043–9.

- Aitchison TC, Sirel JM, Watt DC, MacKie RM (for the Scottish Melanoma Group). Prognostic trees to aid prognosis in patients with cutaneous malignant melanoma. BMJ 1995; 311(7019):1536–9.

- Karakousis CP, Driscoll DL. Prognostic parameters in localised melanoma: Gender versus anatomical location. Eur J Cancer 1995;31A:320–4.

- Scoggins CR, Ross MI, Reintgen DS, Noyes RD, Goydos JS, Beitsch PD, . Gender-related differences in outcome for melanoma patients. Ann Surg 2006;243:693–8.

- de Vries E, Nijsten TE, Visser O, Bastiaannet E, van Hattem S, Janssen-Heijnen ML, . Superior survival of females among 10,538 Dutch melanoma patients is independent of Breslow thickness, histologic type and tumor site. Ann Oncol 2008;19:583–9.

- Sant M, Allemani C, Santaquilani M, Knijn A, Marchesi F, Capocaccia R; EUROCARE Working Group. EUROCARE-4. Survival of cancer patients diagnosed in 1995–1999. Results and commentary. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:931–91.

- Engeland A, Haldorsen T, Tretli S, Hakulinen T, Hörte LG, Luostarinen T, . Prediction of cancer mortality in the Nordic countries up to the years 2000 and 2010, on the basis of relative survival analysis. A collaborative study of the five Nordic Cancer Registries. APMIS 1995;103(Suppl 49): 1–163.

- Engholm G, Gislum M, Bray F, Hakulinen T. Trends in the survival of patients diagnosed with cancer in the Nordic countries 1964–2003 followed up to the end of 2006. Material and methods. Acta Oncol 2010.

- Corazziari I, Quinn M, Capocaccia R. Standard cancer patient population for age standardising survival ratios. Eur J Cancer 2004;40:2307–16.

- Balch CM, Soong SJ, Milton GW, Shaw HM, McGovern VJ, McCarthy WH, . Changing trends in cutaneous melanoma over a quarter century in Alabama, USA, and New South Wales, Australia. Cancer 1983;52:1748–53.

- Garbe C, Eigentler TK. Diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous melanoma: State of the art 2006. Melanoma Res 2007;17:117–27.

- Dummer R, Hauschild A, Pentheroudakis G. Cutaneous malignant melanoma: ESMO clinical recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2009;20 (Suppl 4):iv129–iv131.

- Lasithiotakis KG, Leiter U, Eigentler T, Breuninger H, Metzler G, Meier F, . Improvement of overall survival of patients with cutaneous melanoma in Germany, 1976–2001: Which factors contributed? Cancer 2007;109:1174–82.

- Autier P, Boniol M, Héry C, Masuyer E, Ferlay J. Cancer survival statistics should be viewed with caution. Lancet Oncol 2007;8:1050–2.

- Lindholm C, Andersson R, Dufmats M, Hansson J, Ingvar C, Möller T, . Invasive cutaneous malignant melanoma in Sweden, 1990–1999. A prospective, population-based study of survival and prognostic factors. Cancer 2004;101: 2067–78.

- Ringborg U, Lagerlöf B, Broberg M, Månsson-Brahme E, Platz A, Thörn M. Early detection and prevention of cutaneous malignant melanoma: Emphasis on Swedish activities. Med Oncol Tumor Pharmacother 1991;8:183–7.

- Héry C, Tryggvadóttir L, Sigurdsson T, Ólafsdóttir E, Sigurgeirsson B, Jonasson JG, . A melanoma epidemic in Iceland: Possible influence of sunbed use. Am J Epidemiol 2010 (in press).

- Giles GG, Armstrong BK, Burton RC, Staples MP, Thursfield VJ. Has mortality from melanoma stopped rising in Australia? Analysis of trends between 1931 and 1994. Br Med J 1996;312:1121–5.

- Severi G, Giles GG, Robertson C, Boyle P, Autier P. Mortality from cutaneous melanoma: Evidence for contrasting trends between populations. Br J Cancer 2000;82:1887–91.

- Precursors to malignant melanoma. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement, October 24–26, 1983. J Am Acad Dermatol 1984;10: 683–8.

- MacKie RM, Osterlind A, Ruiter D, Fritsch P, Aapro M, Cesarini JP, . Report on consensus meeting of the EORTC Melanoma Group on educational needs for primary and secondary prevention of melanoma in Europe. Results of a workshop held under the auspices of the EEC Europe against cancer programme in Innsbruck, April 1991. Eur J Cancer 1991;27:1317–23.

- MacKie RM, Hole D. Audit of public education campaign to encourage earlier detection of malignant melanoma. BMJ 1992;304(6833):1012–5.