To the Editor,

Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL) is an aggressive mature T-cell malignancy associated with the human T-cell lymphotropic virus type I (HTLV-I). It is generally characterized by a short survival time and poor response to chemotherapy [Citation1]. ATL has been classified clinically into five distinct types: acute, chronic, lymphomatous, smoldering and primary cutaneous tumoral types [Citation2,Citation3]. The disease affects the skin in 43–72% of cases and may present as erythroderma, plaques, papules and, less frequently, as nodules and tumors [Citation3]. Specific purpuric lesions as a primary manifestation of the disease are rare. To the best of our knowledge, only nine cases of diffuse purpuric lesions resulting from ATL cell infiltration have been reported up to the present moment and all of these cases occurred in Japan (), four in cases of acute ATL and four in smoldering ATL. In the remaining case, no information was available [Citation4–6]. The present report refers to a case of acute ATL in which the patient presented with large, disseminated purpuric skin lesions constituting the only cutaneous manifestation of disease.

Table I. Reports of adult cell leuykemia/lymphoma with specific purpuric lesions.

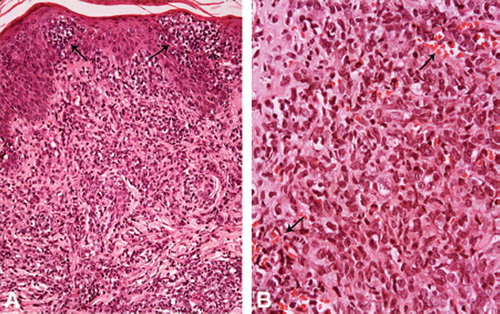

An 87-year-old male patient, born and living in Salvador, Brazil, presented with disseminated cutaneous purpuric papular lesions on his trunk, limbs and palm over the previous 45 days, that had converged to form infiltrated plaques (). At presentation, the purpuric lesions appeared to be the only manifestation of the disease; however, the patient then went on to develop enlarged inguinal lymph node. He also complained of loss of appetite and weight loss. He was HTLV-1 positive, as detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), HIV-negative, and had been breastfed for five years as a baby. Laboratory tests revealed leukocytosis (63 200/mm3), lymphocytosis (38 600/mm3), thrombocytopenia (31 000/mm3), a marked increase in lactate dehydrogenase to 4.5 times the upper normal limit, slightly elevated levels of creatinine and normal levels of blood urea nitrogen and serum calcium. Blood smear examination revealed 26% of flower cells. A peripheral blood sample was analyzed using flow cytometry and cell surface markers indicated that 84% of the atypical cells were CD3+, CD4+, CD7− and CD25+. Skin biopsy showed Pautrier's abscesses with atypical lymphocytes and a dense infiltration of medium-sized and pleomorphic lymphocytes in the upper and middle dermis (). Some extravasated erythrocytes were found amidst the neoplastic cells (). Evaluation using Perls’ iron stain revealed small foci with hemosiderin deposition. No vasculitis was observed. The lymphocytes were OPD4+, CD3+, CD4+, CD5+, CD7−, CD8−, CD20−, CD25+ and CD79a−. Ki-67 proliferation index was 50%. Morphologically, this pattern is similar to that of peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified. Considering the clinical, laboratory and pathological characteristics of the present case, a diagnosis of acute ATL was made. No other skin lesions were observed during the course of the disease. The patient was given interferon-α for 20 days but failed to respond to treatment. He died of pneumonia one month after being admitted to hospital.

Figure 2. Skin biopsy showing: A. Pautrier microabscesses (arrows) with pleomorphic and medium lymphocytes also present in the superficial and medium dermis. HE, × 100; B. The dermal neoplastic infiltration with extravasated erythrocytes (arrows). HE, × 320.

This case was classified as acute ATL due to the high lymphocyte counts, the presence of high lactate dehydrogenase levels and the circulating flower cells, a feature considered pathognomonic of acute ATL [Citation8] and because histologic findings were indicative of peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified. Furthermore, cell surface phenotype analysis of lymphocytes by flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry of the skin biopsy showed a result of CD3+, CD4+, CD7−, CD8− and CD25+, a phenotype classically considered representative of ATL [Citation7]. Peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified is the most common histological pattern observed in ATL [Citation1]. However, this patient had no hypercalcemia, a characteristic commonly found in the acute form of the disease.

As a primary manifestation of the disease, purpuric lesions due to ATL cell infiltration are very rare, although they are sometimes found as secondary lesions in acute ATL due to the thrombocytopenia that is often seen in this form of the disease [Citation4,Citation8]. Of the 52 cases of ATL detected in Bahia, Brazil in which presentation was cutaneous, it was only in the current case that specific purpuric lesions were found [Citation3]. Considering that the lesions in this case were infiltrated and certainly specific, and that the patient presented with marked thrombocytopenia, these lesions may have occurred due to the lymphomatous infiltration associated with thrombocytopenia. Although other factors may be involved in the hemorrhagic process, it is very likely that this may be a result of cytokines produced by tumor cells.

It has already been documented that in ATL, CD25+ tumor cells have the potential to produce cytotoxic molecules such as granzyme B, the secretion of which leads to vessel destruction [Citation5].

Acute ATL is one of the most severe forms of the disease and one that requires prompt diagnosis to ensure that appropriate therapy is initiated as early as possible. The median survival time of patients with acute ATL varies from four to six months [Citation1,Citation2]. However, in the present case, the patient survived only four weeks after diagnosis and there was insufficient time for the treatment to be effective. Nowadays, the treatment of choice is IFN-α/AZT, a therapeutic regimen that has led to a considerable improvement in patients’ prognosis [Citation9].

Considering that the skin is often involved in the different types of ATL, skin lesions may represent the first sign of the disease. It is important for ATL to be taken into consideration in the differential diagnosis of infiltrated purpuric lesions with no other manifestation. Clinicians need to be informed of these characteristics and laboratory analysts need to be aware that flower cells in peripheral blood may represent an early feature of acute ATL [Citation10].

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Bittencourt AL, Vieira MG, Brites CR, Farré L, Barbosa HS. Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL) in Bahia, Brazil: Analysis of prognostic factors in a group of 70 patients. Am J Clin Pathol 2007;128:875–82.

- Shimoyama M; and members of the Lymphoma Study Group. Diagnostic criteria and classification of clinical subtypes of adult T-cell leukaemia-lymphoma. Br J Haematol 1991;79:428–7.

- Bittencourt AL, Barbosa HS, Vieira MD, Farré L. Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL) presenting in the skin: Clinical, histological and immunohistochemical features of 52 cases. Acta Oncol 2009;48:598–604.

- Okada J, Imafyku S, Tsujita J, Morol Y, Urabe K, Furue M. Case of adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma manifesting marked purpura. J Dermatol 2007;34:782–5.

- Shimauchi T, Hirokawa Y, Tokura Y. Purpuric adult T-cell leukaemia/lymphoma: Expansion of unusual CD4/CD8 double-negative malignant T cells expressing CCR4 but bearing the cytotoxic molecule granzyme B. Br J Dermatol 2005;152: 350–2.

- Tabata R, Tabata C, Namiuchi S, Terada M, Yasumizu R, Okamoto T, . Adult T-cell lymphoma mimicking Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Mod Rheumatol 2007;17:57–62.

- Ohshima K, Jaffe ES, Kikuchi M. Adult T-cell leukaemia/lymphoma. Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, . WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Lyon; WHO: 2008. 281–4.

- Tsukasaki K, Hermine O, Bazarbachi A, Ratner L, Ramos JC, Harrington W Jr, . Definition, prognostic factors, treatment, and response criteria of adult T-cell leukemialymphoma: A proposal from an International Consensus Meeting. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:453–9.

- Bazarbachi A, Plumelle Y, Ramos JC, Tortevoye P, Otrock Z, Taylor G, . Meta-analysis on the use of zidovudine and interferon-alfa in adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma showing improved survival in the leukemic subtypes. J Clin Oncol 2010 (in press).

- Santos JB, Farré L, Batista Eda S, Santos HH, Vieira MD, Bittencourt AL. The importance of flower cells for the early diagnosis of acute adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma with skin involvement. Acta Oncol 2010;49:265–7.