Abstract

Purpose. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials was performed to compare the efficacy, quality of life (QOL), symptom improvement and toxicities of gefitinib with docetaxel in previously treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Methods. The PubMed database, the Cochrane Library and references of published trials were searched. Two reviewers independently assessed the quality of the trials and extracted data. The hazard ratios (HRs) for overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS), relative risks (RRs) for overall response rate, QOL and symptom improvement, and odds ratios (ORs) for main toxicities were pooled using STATA package. Results. Four multicenter, randomized controlled trials involving 2257 patients with previously treated advanced NSCLC were ultimately analyzed. The pooled HRs showed no significant difference in OS and PFS between the two groups (HR = 1.02, 95% CI = 0.92–1.12, p = 0.70; HR = 0.97, 95% CI = 0.88–1.07, p = 0.57, respectively). Gefitinib significantly improved overall response rate (RR = 1.58, 95% CI = 1.02–2.45, p = 0.04) and QOL (RR = 1.55, 95% CI = 1.27–1.88, p = 0.00 by Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Lung and RR = 1.86, 95% CI = 1.43–2.42, p = 0.00 by Trial Outcome Index, respectively). Gefitinib had fewer grade 3 or 4 neutropenia and fatigue (OR = 0.02, 95% CI = 0.01–0.03, p = 0.00; and OR = 0.47, 95% CI = 0.32–0.70, p = 0.00, respectively), but more grade 3 or 4 rash (OR = 2.87, 95% CI = 1.24–6.63, p = 0.01) than docetaxel. The grade 3 or 4 nausea, vomiting and diarrhea and symptom improvement were comparable between the two drugs. Conclusions. In conclusion, although similar OS and PFS, gefitinib showed an advantage over docetaxel in terms of objective response rate, QOL and tolerability. Therefore, gefitinib is an important and valid treatment option for previously treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients.

Lung cancer is one of the most common forms of cancer in the world, in terms of incidence and mortality, with over one million new cases annually [Citation1]. Non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for at least 80% of all lung cancer cases, presenting as locally advanced disease in approximately 25 to 30% of cases and as metastatic disease in approximately 40 to 50% of cases [Citation2]. Treatment for these patients consists of chemotherapy, supportive care and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) for patients with EGFR mutations [Citation3,Citation4], but response rates are modest and recurrence eventually occurs for most patients after standard first-line therapy.

In TAX317 study, docetaxel could significantly prolong survival compared with best supportive care in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy [Citation5]. Therefore, docetaxel was recommended as second-line treatment for patients with advanced NSCLC by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) [Citation3]. However, docetaxel is associated with significant toxicity, including hematological toxicity, neurotoxicity, and asthenia. Molecular-targeted agents such as gefitinib, an oral EGFR-TKI, have been investigated as potential alternatives to increase efficacy or reduce toxicity in this disease setting. Gefitinib 250 mg/d showed clinically significant antitumor activity, as well as favorable tolerability in pretreated patients with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC in two phase II studies [Citation6,Citation7]. Although the difference in survival between gefitinib and placebo in ISEL study did not reach significance, the time to treatment failure and objective-response rate were significantly improved in gefitinib [Citation8]. What's more, the efficacy of gefitinib was similar or non-inferior to docetaxe in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer [Citation9,Citation10]. Consequently, gefitinib was also recommended as second-line treatment for patients with advanced NSCLC by ASCO [Citation3]. The SIGN study, a phase II, open-label, randomized study, found the efficacy of gefitinib was similar to docetaxel with a more favorable tolerability profile in the second-line treatment of advanced NSCLC [Citation9]. Another three phase III, open-label, randomized studies were conducted subsequently to compare the efficacy and toxicity of gefitinib with docetaxel in previously treated advanced NSCLC [Citation10–12]. But, the results were inconsistent. The objectives of this meta-analysis were to compare the efficacy and toxicities of gefitinib with docetaxel in previously treated advanced NSCLC.

Patients and methods

Searching

In May 2009, an electronic search of the PubMed database, the CENTRAL (the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials) database was performed. The following keywords were used: “non-small-cell lung cancer”, “Carcinoma, Non-small-cell Lung”, “gefitinib” and “Iressa”. The search was limited in “Randomized Controlled Trial”. The published languages and years were not limited. Reference lists of original articles and review articles were also examined for additional trials.

Selection of trials

Trials meeting the following inclusion criteria were eligible: 1. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs); 2. Patients were histologically or cytologically confirmed stage IIIB or IV NSCLC; 3. Patients received at least one previous chemotherapy regimen; 4. Studies comparing the efficacy and toxicity of gefitinib with docetaxel; 5. Trials published in full texts. Trials were excluded if they did not meet with above inclusion criteria.

Validity assessment

An open assessment of the trials was performed using the methods reported by Jadad and colleagues, which assessed the trials according to the following three questions: 1. whether reported an appropriate randomization method (0 to 2 scores); 2. whether reported an appropriate blinding method (0 to 2 scores); 3. whether reported withdrawals and dropouts (0 to 1 score) [Citation13].

Data abstraction

All the data were independently abstracted by two investigators (J.J. and L.H.) with the use of standardized data-abstraction forms. Disagreements were resolved by discussion with an independent expert (X.L.). The following information were sought from each paper, although some papers did not contain all of them: trial's name, first author, year of publication, journal, quality scores according to Jadad and colleagues’ methods, ethnicity, number of patients in both groups, median age, and patient percentage of female, performance status (PS) 0 to1, non-smokers, locally advanced disease and adencarcinoma, hazard ratios (HRs) for overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs), number of patients acquired overall response assessed with Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST), number of patients acquired quality of life (QOL) improvement assessed with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Lung (FACT-L) questionnaire total score and trial outcome index (TOI) and patients acquired symptom improvement assessed with the FACT-L lung cancer subscale (LCS), main grade 3 or 4 toxicity data such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, neutropenia, fatigue and rash.

Statistical analysis

HRs for OS and PFS, relative risk (RR) for overall response to treatment, QOL and symptom improvement, and odds ratios (ORs) for different types of toxicity were calculated using STATA SE 10.1 package. Analyses were performed in intention-to-treatment (ITT) for OS, PFS and overall response, in evaluable population for QOL, symptom improvement and toxicities. A statistical test with a p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant. HR > 1 reflects more deaths or progression in gefitinib group, RR > 1 reflects more overall response, QOL improvement or symptom improvement in gefitinib group, and OR > 1 indicates more toxicities in gefitinib group; and vice versa. To investigate statistical heterogeneity between trials, the standard χ2 Q-test was applied (meaningful differences between studies indicated by p < 0.10). The results were generated using fixed-effect model. A random-effect model was employed when there was evidence of significantly statistical heterogeneity, generating a more conservative estimate [Citation14]. All p-values were two-sided. All CIs had a two-sided probability coverage of 95%.

Results

Trial flow

Thirty-two reports were retrieved originally after electronic searching, and six reports [Citation9–12,Citation15,Citation16] were identified after scanning the titles and abstracts. Two reports [Citation15,Citation16] were excluded for following reasons: one [Citation15] reported molecular predictors of outcome with gefitinib and docetaxel in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer from the INTEREST trial, main results of which were reported by Kim and colleagues [Citation10], the other one [Citation16] reported Quality of Life and disease-related symptoms of gefitinib versus docetaxel in previously treated Japanese patients with non-small-cell lung cancer from V-15-32 study, main results of which were reported by Maruyama and colleagues [Citation11]. Thus, four randomized controlled trials [Citation9–12] involving 2257 patients with previously treated advanced NSCLC were ultimately analyzed.

Characteristics of the four trials

All the four trials were multicenter, randomized, open-label studies and were published in full texts and in English. One [Citation9] of them was phase II RCT and the others were phase III RCTs. Baseline characteristics of the four trials are listed in . In total, 2257 patients with previously treated advanced NSCLC were randomized to receive gefitinib (1128 patients) or docetaxel treatment (1129 patients). Gefitinib 250 mg/d was administered orally; docetaxel 75 mg/m2 (in V-15-32 studies the dose of docetaxel was 60 mg/m2) was administered every three weeks intravenously. Except ISTANA study [Citation12] which limited the maximum docetaxel administration to six cycles, all patients received treatment until disease progression, intolerable toxicity, or discontinuation for some other reasons.

Table I. Characteristics of the four trails comparing gefitinib with docetaxel in previously treated advanced NSCLC.

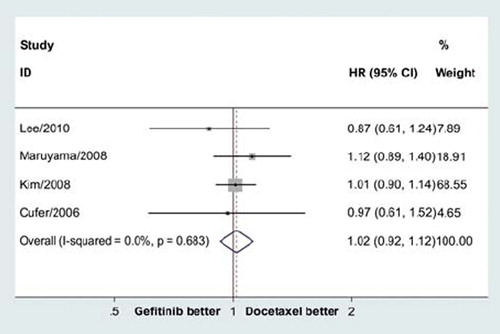

Overall survival

The pooled HR for OS didn't show significant difference in overall survival between gefitinib and docetaxel groups (HR = 1.02, 95% CI = 0.92–1.12, p = 0.70; ). There was no significant heterogeneity (p = 0.68), and the pooled HR for OS was performed using fixed-effort model.

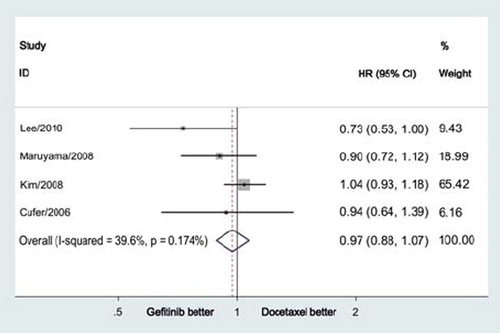

Progression-free survival

The pooled HR for PFS also failed to display a difference between gefitinib and docetaxel groups (HR = 0.97, 95% CI = 0.88–1.07, p = 0.57; ). There was no significant heterogeneity (p = 0.17), and the pooled HR for PFS was performed using fixed-effort model.

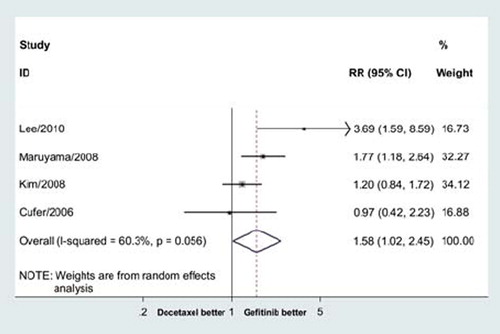

Overall response

The ORRs for gefitinib and docetaxel were 13.03% and 8.59%, respectively. The pooled RR for ORR showed gefitinib significantly improved overall response rate (RR = 1.58, 95% CI = 1.02–2.45, p = 0.04; ). The number need to treat (NNT) was 23.

Figure 3. Meta-analysis showed that gefitinib significantly improved overall response rate compared with docetaxe in previously treated advanced NSCLC (RR = 1.58, 95% CI = 1.02–2.45, p = 0.04).

There was significant heterogeneity (p = 0.06), and the pooled RR for overall response was performed using random-effort model.

Quality of life and symptom improvement

The pooled RRs indicated that gefitinib significantly improved QOL both by FACT-L questionnaire total score and by TOI questionnaire (RR = 1.55, 95% CI = 1.27–1.88, p = 0.00 by FACT-L and RR = 1.86, 95% CI = 1.43–2.42, p = 0.00 by TOI, respectively, ) compared with docetaxel. However, the meta-analysis didn't show a symptom improvement of gefitinib compared with docetaxel ().

Table II. Results of the meta-analysis for QOL, symptom improvement and main grade 3 or 4 toxicities.

Toxicities

Docetaxel resulted in 60.1% grade 3 or 4 neutropenia and 6.9% grade 3 or 4 fatigue. The meta-analyses showed that the risks of grade 3 or 4 neutropenia and fatigue of docetaxel were more than gefitinib (OR = 0.02; 95% CI = 0.01–0.03, p = 0.00; OR = 0.47; 95% CI = 0.32–0.70, p = 0.00; respectively, ). Gefitinib resulted in 1.9% grade 3 or 4 rash. The pooled OR indicated the risk of grade 3 or 4 rash of gefitinib were more than docetaxel (OR = 2.87; 95% CI = 1.24–6.63, p = 0.01; respectively, ). The grade 3 or 4 nausea, vomiting and diarrhea were comparable between gefitinib and docetaxel ().

Publication bias

A number of steps were included in the study design to minimize the potential for publication bias. Firstly, the search strategy was extensive; secondly, papers were selected strictly according to inclusion criteria; thirdly, publication bias was detected by several methods. Publication bias was not found according to funnel plot, Begg's test [Citation17] (p = 0.73) and Egger's test [Citation18] (p = 0.69).

Discussion

Docetaxel, erlotinib, gefitinib, or pemetrexed is acceptable as second-line therapy for patients with advanced NSCLC with adequate performance status (PS) when the disease has progressed during or after first-line, platinum-based therapy [Citation3]. Both docetaxel and pemetrexed were cytotoxic drugs, and both erlotinib and gefitinib were EGFR-TKIs. Several randomized controlled trials indicated that EGFR-TKI gefitinib had equivalent or similar efficacy as docetaxel with a more favorable quality of life and tolerability profile. SIGN, which didn't include Asian patients, a multicenter, randomized, parallel-group, open-label, phase II trial investigated oral gefitinib or i.v. docetaxel in patients with advanced NSCLC who had previously received one chemotherapy regimen, and showed that efficacy of gefitinib was similar to docetaxel in according to OS, PFS, ORR, QOL and symptom improvement rates, with a more favorable tolerability profile [Citation9]. INTEREST, a global study on 1466 patients, showed noninferiority of gefitinib (250 mg/d) relative to docetaxel (75 mg/m2 every 3 weeks) in terms of overall survival, with similar progression-free survival and objective response rate and a more favorable quality of life and tolerability profile [Citation10]. The third study, V-15-32, a Japanese study on 489 patients, failed to meet its primary objective of showing noninferiority in overall survival between gefitinib (250 mg/d) and docetaxel (60 mg/m2 every 3 weeks) but found no significant difference between gefitinib and docetaxel in terms of overall survival and progression-free survival, and a higher objective response rate and QOL for gefitinib [Citation11]. The fourth RCT, ISTANA compared gefitinib with docetaxel as monotherapy in previously treated Korean patients with advanced NSCLC, and showed that gefitinib improved progression-free survival compared with docetaxel (hazard ratio, 0.729; 90% CI, 0.533–0.998) with significantly improved objective response rate (28.1% versus 7.6%) [Citation12].

The different results of the four studies motivated the present meta-analysis. The results of the meta-analysis showed that gefitinib significantly improved overall response rate and QOL. However, the improved overall response rate and QOL didn't transfer into a prolonged OS for gefitinib as reported by Tsujino and colleagues that response rate was associated with prolonged survival in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer treated with gefitinib or erlotinib [Citation19]. The possible explanation for the divergence was that cross-over to the alternative therapy at disease progression rendered it impossible to detect an OS benefit because many patients received both treatments, but in a different sequence. Poststudy, 31%, 36% and 29.6% patients of gefitinib group received subsequent docetaxel in INTEREST, V-15-32, and ISTANA studies, respectively; and 37%, 53% and 67.1% patients of docetaxel group received subsequent EGFR-TKIs (gefitinib or erlotinib) in INTEREST, V-15-32, and ISTANA studies, respectively. The patients in docetaxel group received subsequent EGFR-TKIs were more than the patients in gefitinib group received subsequent docetaxel. Shepherd and colleagues also presented a similar meta-analysis at ASCO 2009 using the same four randomized controlled trials. We obtained the same results as Shepherd and colleagues according to OS, PFS and ORR. Shepherd and colleagues did not analyze the QOL, symptom improvement and toxicities between gefitinib and docetaxel [Citation20].

The results in our meta-analysis showed that gefitinib significantly improved QOL, but not symptom improvement. As for toxicities, the pooled ORs showed that the risks of grade 3 or 4 neutropenia and fatigue of docetaxel were more than gefitinib. However, the risk of grade 3 or 4 rash of gefitinib was more than docetaxel. The grade 3 or 4 nausea, vomiting and diarrhea were comparable between gefitinib and docetaxel. Therefore, the tolerability of gefitinib was better than docetaxel.

None of the four trials selected patients according to EGFR status. As gefitinib was an EGFR-TKI, did the EGFR protein expression, EGFR copy number or EGFR mutation affect the efficacy of gefitinib in the second-line therapy, and should the patients with previously treated advanced NSCLC measure the EGFR status for selecting gefitinib or docetaxel? In the Iressa Survival Evaluation in Lung Cancer (ISEL) study comparing gefitinib with placebo in pretreated patients with advanced NSCLC [Citation8], both EGFR protein expression and high EGFR copy number were predictors of a gefitinib-related effect on survival, with significant interactions between biomarker status and survival outcome [Citation21]. However, although patients with EGFR mutation positive tumors were associated with prolonged PFS and improved ORR in gefitinib group compared with docetaxel group, EGFR status analyses of tumors from a subset of patients in the INTEREST trial didn't find a significant difference in OS between gefitinib group and docetaxel group in patients with EGFR high copy number, low copy number, protein expression positive, protein expression negative, mutation positive, or wild-type tumors [Citation15]. One possible explanation for the divergence was that overall survival of patients treated with gefitinib may be similar to docetaxel despite EGFR status, and another possible explanation for the divergence was cross-over to the alternative therapy at disease progression. Therefore, gefitinib is an important option for unselected population with previously treated advanced NSCLC. It is badly in need of a prospective randomized controlled trial to compared gefitinib and docetaxel in second-line treatment in selected population according to EGFR status.

The meta-analysis was based on the data from the published literature, but not individual patient data (IPD).

In conclusion, although similar OS and PFS, gefitinib showed an advantage over docetaxel in terms of objective response rate, QOL and tolerability. Therefore, gefitinib is an important and valid treatment option for previously treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients.

Acknowledgements

The analysis of the pooled data was supported by a grant from the scientific research foundation of Huashan Hospital Fudan University. All the authors indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Estimating the world cancer burden: Globocan 2000. Int J Cancer 2001;94: 153–6.

- Novello S, Le Chevalier T. Chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer. Part 1: Early-stage disease. Oncology (Williston Park) 2003;17:357–64.

- Azzoli CG, Baker S Jr, Temin S, Pao W, Aliff T, Brahmer J, . American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline update on chemotherapy for stage IV non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009;7:6251–66.

- Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, Yang CH, Chu DT, Saijo N, , Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med 2009;361:947–57.

- Shepherd FA, Dancey J, Ramlau R, Mattson K, Gralla R, O'Rourke M, , Prospective randomized trial of docetaxel versus best supportive care in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:2095–103.

- Fukuoka M, Yano S, Giaccone G, Tamura T, Nakagawa K, Douillard JY, . Multi-institutional randomized phase II trial of gefitinib for previously treated patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (The IDEAL 1 Trial) [corrected]. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:2237–46.

- Kris MG, Natale RB, Herbst RS, Lynch TJ, Prager D Jr, Belani CP, . Efficacy of gefitinib, an inhibitor of the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase, in symptomatic patients with non-small cell lung cancer: A randomized trial. JAMA 2003;290:2149–58.

- Thatcher N, Chang A, Parikh P, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, Pawel J von, . Gefitinib plus best supportive care in previously treated patients with refractory advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: Results from a randomised, placebo-controlled, multicentre study (Iressa Survival Evaluation in Lung Cancer). Lancet 2005;366:1527–37.

- Cufer T, Vrdoljak E, Gaafar R, Erensoy I, Pemberton K. Phase II, open-label, randomized study (SIGN) of single-agent gefitinib (IRESSA) or docetaxel as second-line therapy in patients with advanced (stage IIIb or IV) non-small-cell lung cancer. Anticancer Drugs 2006;17:401–9.

- Kim ES, Hirsh V, Mok T, Socinski MA, Gervais R, Wu YL, . Gefitinib versus docetaxel in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (INTEREST): A randomised phase III trial. Lancet 2008;372:1809–18.

- Maruyama R, Nishiwaki Y, Tamura T, Yamamoto N, Tsuboi M, Nakagawa K, . Phase III study, V-15-32, of gefitinib versus docetaxel in previously treated Japanese patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26:4244–52.

- Lee DH, Park K, Kim JH, Lee JS, Shin SW, Kang JH, . Randomized Phase III trial of gefitinib versus docetaxel in non-small cell lung cancer patients who have previously received platinum-based chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res 2010;16:1307–14.

- Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghanet DJ, . Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 1996;17:1–12.

- Deeks J, Altman D, Bradburn M. Statistical methods for examining heterogeneity and combining results from several studies in meta-analysis. Egger M, Smith GR, Altman DG, Systematic reviews in health care: Meta-analysis in context. 2nd London, UK: BMJ Books; 2001 285–312.

- Douillard JY, Shepherd FA, Hirsh V, Mok T, Socinski MA, Gervaiset R, . Molecular predictors of outcome with gefitinib and docetaxel in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer: Data from the randomized phase III INTEREST trial. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:744–52.

- Sekine I, Ichinose Y, Nishiwaki Y, Yamamoto N, Tsuboi M, Nakagawa K, . Quality of life and disease-related symptoms in previously treated Japanese patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: Results of a randomized phase III study (V-15-32) of gefitinib versus docetaxel. Ann Oncol 2009;20:1483–8.

- Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 1994;50: 1088–101.

- Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997; 315:629–34.

- Tsujino K, Kawaguchi T, Kubo A, Aono N, Nakao K, Koh Y, . Response rate is associated with prolonged survival in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer treated with gefitinib or erlotinib. J Thorac Oncol 2009;4:994–1001.

- Shepherd FA, Douillard J, Fukuoka M, Saijo N, Kim S, Cufer T, . Comparison of gefitinib and docetaxel in patients with pretreated advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): Meta-analysis from four clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:15s (Suppl; abstr 8011).

- Hirsch FR, Varella-Garcia M, Bunn PA Jr, Franklin WA, Dziadziuszko R, Thatcher N, . Molecular predictors of outcome with gefitinib in a phase III placebo-controlled study in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:5034–42.