To the Editor,

Actinomycosis is a rare non-contiguous infection caused by actinomyces, which is a gram-positive, rather micro aerophilic bacterium. Regularly actinomyces is part of the normal flora in the intestinum, anal canal and genital tracts. Typical locations for local site infection are the cervicofacial and abdominopelvic region [Citation1]. Primary anorectal actinomycosis and perianal actinomycosis are very rare. It is suggested, that in coloproctology two different types of anorectal actinomycosis can be differentiated: primary rectal actinomycosis and perianal actinomycosis [Citation2].

Here we report a case of undetected actinomyces infection in a T3 rectal cancer located 7 cm above the anal verge. Preoperative therapy consisted of radiochemotherapy with 5-FU. The actinomyces infection mimicked tumor progression. The patient underwent laparoscopic anterior resection. However, the concrete-like adhesion made sphincter-preserving resection difficult. Histological evaluation revealed an ypT0 status and a large actinomycosis-associated pseudotumor.

Case report

A 54-year-old otherwise healthy male patient was admitted to the hospital because of rectal bleeding. The digital examination revealed a Mason III rectal tumor at the fingertip [Citation3]. The endoscopy showed a rectal cancer lesion in 7 cm distance from the anal verge. Similar results of a T3 situation were observed in the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan as well as in the endosonography. The nodal status was negative in both examinations. Histology showed a rectal cancer of moderate differentiation. In a retrospective analysis no evidence for actinomycosis was found in the biopsy specimen.

Neoadjuvant treatment

According to these findings an interdisciplinary tumor board recommended neoadjuvant chemoradiation, which was delivered as three-dimensional (3D) conformal radiotherapy with 5 fractions per week of 1.8 Gy to a total dose 50.4 Gy. Surgery was performed five weeks after end of radiochemotherapy. The treatment course was uneventfully for the first three weeks of radiotherapy. During the last two weeks the patient complained of progressive rectal pain. The pain aggravated with main extension into the penis and the testes and was refractory to analgetics.

Preoperative evaluation

A MRI and rectoscopy four weeks after the end of radiotherapy showed a progressive tumor. In the rectoscopy, the distance to the anal verge was shortened to 4 cm. In contrast to the evaluation prior to radiotherapy, sphincter-preserving surgery was insecure due to the short distance to the sphincteric muscle.

Surgery

The patient underwent laparoscopic anterior rectal resection. During surgery the large tumor was difficult to excise due to a concrete-like adhesion, although the surgical planes were intact. During surgery it was decided to transect the rectum in the lower muscle tube, approximately 2 cm from the anal verge. A colorectal Baker-pouch anastomosis was stapled using a 28 mm stapling device in an end-to-side fashion under ileostomy protection. The postoperative course under ERAS protocol was uneventful, bowel movements were registered from the second postoperative day and the patient left the hospital six days after surgery [Citation4].

Histologic examination

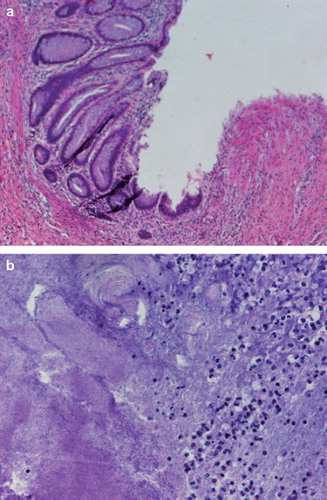

The macroscopic evaluation of the specimen showed a tumor 5cm in diameter (). The tumor was located 2 cm proximal to the resection margin. The histology revealed a grade 4 tumor regression according to the Dworak categorization with no evidence of remaining tumor cells and inflammatory response typical to actinomyces infection with clusters of actinomyces granulomas so called “Actinomyces-Drusen” ( and ) [Citation5].

Discussion

Human actinomycosis was first described by Israel in 1878 when he isolated the causative agent and gave it his name [Citation6]. Because of its morphologic features, initially it was thought to be a fungus, but it is actually a bacterium.

Gastrointestinal actinomycosis manifests usually as a slowly growing mass, caused by penetration of actinomyces through the intestinal wall. Frequently there is sinus formation to the skin. In the gastrointestinal tract in most cases the infection is located in the appendix or the coecum. Other common locations are gastric, prepyloric and in the sigmoid colon, but almost every other location in the intestine is possible [Citation7].

Obviously, one essential condition for the infection is a mucosal or skin lesion in the rectum or the anal canal. Typically, this is an anal fistula with a pre-existing local site infection [Citation1,Citation8]. The mucosal lesion in this case was the ulcerative rectal cancer. Actinomyces infection is often associated with some kind of suppressed immunosystem. Coremans et al. reported of a striking association of anorectal actinomycosis with diabetes mellitus and other predispositions such as HIV infection and alcoholism [Citation2]. In this context, the radiochemotherapy might have had an impact on the development of the actinomyces infection. Although, no reports exist of growing actinomycosis under radiochemotherapy, it was the only potential immunosuppressor in this case.

It might be too speculative, that the actinomyces infection itself has contributed to the complete tumor response. However, one potential explanation might be linked to a general immune stimulus due to the bacterial infection. Another possible explanation might be a sensitizing effect of the bacterium itself making neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy more effective. As suggested by Mlecnik et al., the strength of the immune reaction could advance our understanding of cancer evolution and have important consequences in clinical practice [Citation9].

Tumor progression of rectal cancer during radiotherapy is very uncommon. Regularly, tumor shrinkage can be observed after long course radiotherapy [Citation10]. Theodoropoulos et al. reported of only one case of tumor progression during preoperative radiotherapy with 45 Gy of 88 patients treated [Citation11].

The tumor growth during radiotherapy was unexpected and made sphincter-preserving surgery uncertain. Definitely, the distance to the anal verge was shorter than expected. Thus, a very low colorectal pouch anastomosis became necessary.

One fact that does not fit the observations in the literature is that the patient complained of severe pain. Usually actinomyces associated infection show up with a painless perianal mass. Coremans et al. recently reported of three cases with a perianal induration. In two of the three cases an anal fistula and immunosuppression [Citation2]. Magdeburg et al. also described a case of a perianal mass and abscess formation without substantial pain [Citation1].

In conclusion, here we describe to the best of our knowledge for the first time a case of actinomyces infection causing a large pseudotumor in the rectum during neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy for rectal cancer. The clinical tumor progression made surgery difficult and enforced a very low rectal resection with colorectal anastomosis. Fortunately, the preoperative radiochemotherapy resulted in a histological complete response (ypT0) of the rectal cancer.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

References

- Magdeburg R, Grobholz R, Dornschneider G, Post S, Bussen D. Perianal abscess caused by Actinomyces: Report of a case. Tech Coloproctol. 2008;12:347–9.

- Coremans G, Margaritis V, Van Poppel HP, Christiaens MR, Gruwez J, Geboes K, . Actinomycosis, a rare and unsuspected cause of anal fistulous abscess: Report of three cases and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:575–81.

- Nicholls RJ, Mason AY, Morson BC, Dixon AK, Fry IK. The clinical staging of rectal cancer. Br J Surg 1982;69:404–9.

- Schwenk W, Gunther N, Wendling P, Schmid M, Probst W, Kipfmuller K, . “Fast-track” rehabilitation for elective colonic surgery in Germany – prospective observational data from a multi-centre quality assurance programme. Int J Colorectal Dis 2008;23:93–9.

- Dworak O, Keilholz L, Hoffmann A. Pathological features of rectal cancer after preoperative radiochemotherapy. Int J Colorectal Dis 1997;12:19–23.

- Israel J. Neue Beobachtungen auf dem Gebiete der Mykosen des Menschen. Archiv Path Anat Phys Klin Med 1878;74:15–53.

- de Feiter PW, Soeters PB. Gastrointestinal actinomycosis: An unusual presentation with obstructive uropathy: Report of a case and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum 2001;44:1521–5.

- Privitera A, Milkhu CS, Datta V, Rodriguez-Justo M, Windsor A, Cohen CR. Actinomycosis of the sigmoid colon: A case report. World J Gastrointest Surg 2009;1:62–4.

- Mlecnik B, Bindea G, Pages F, Galon J. Tumor immunosurveillance in human cancers. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2011;30:5–12.

- Jacques AE, Rockall AG, Alijani M, Hughes J, Babar S, Aleong JA, . MRI demonstration of the effect of neoadjuvant radiotherapy on rectal carcinoma. Acta Oncol 2007;46:989–95.

- Theodoropoulos G, Wise WE, Padmanabhan A, Kerner BA, Taylor CW, Aguilar PS, . T-level downstaging and complete pathologic response after preoperative chemoradiation for advanced rectal cancer result in decreased recurrence and improved disease-free survival. Dis Colon Rectum 2002;45:895–903.