To the Editor,

Pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma (PACC) is a rare tumor with a poor prognosis in the absence of surgery. Moreover, there is currently no standard chemotherapy for metastatic PACC.

We report the case of a patient treated by the FOLFOX 4 regimen with an objective response and a prolonged tumor control and we provide a review of chemotherapy regimens reported for PACC in the literature.

Case report

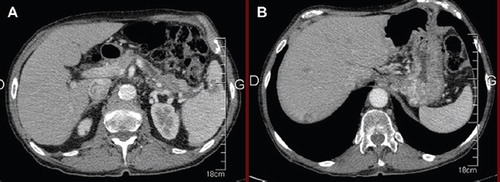

A 79-year-old man, whose main medical history was a prostatic cancer (2004) treated by hormone therapy and radiotherapy with complete remission, was admitted in March 2009 following three months of painful erythematous subcutaneous nodules mainly located on both lower limbs. Performance Status was good (ECOG 1) with, however, a 4 kg weight loss within the past three months. The patient described also for several months slight transitory pain in the left side of the abdomen. The skin lesions evolved typically from erythematous and painful infiltrated plaques, secondly ulcerated with emission of subcutaneous fat, resolving into hyperpigmented scars. Skin biopsy showed focal subcutaneous fat necrosis, pathognomonic of pancreatic panniculitis, suggesting an underlying pancreatic disease. The serum lipase level was markedly elevated (5000 UI/l). As for tumor markers, levels of CEA and CA 19-9 were low. A computed tomography (CT)-scan showed an infiltrating mass in the tail of the pancreas with spleen invasion and four suspect lesions in the liver (). The biopsy of liver metastasis revealed a secondary localization of a pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma.

Figure 1. March 2009 (A) CT-scan revealing the pancreatic tumor with spleen invasion (B) liver metastasis. CT, computed tomography.

A weekly chemotherapy with gemcitabine (1000 mg/m2 weekly) was introduced. In addition, considering the disabling skin lesions, a systemic corticotherapy was initiated in the same time (prednisone 1 mg/kg/day for three days and then 30 mg per day).

After two months of treatment, the patient presented a marked weakness with a 7 kg weight loss and a worsening of the skin eruption, without any improvement after corticosteroids were increased. On imaging, liver metastases had increased in size and number (unequivocal progression > 50% by RECIST), although the pancreatic mass was stable in size ().

Then second-line chemotherapy was begun with the FOLFOX4 regimen. A clinical benefit was quickly observed as after only two courses skin lesions gradually improved and after four courses all lesions were almost healed, and the patient had recovered 5 kg and a good Performance Status. The clinical impression was reinforced by morphological assessment: the CT-scan showed a dramatic decrease of the pancreatic mass and of the liver metastases (> 50% by RECIST). After eight courses, the clinical good evolution was confirmed by an additional decrease of the pancreatic lesion and of the liver metastases (25% by RECIST), and serum lipase level was 130 UI/l. The treatment had to be stopped after 12 courses in December 2009 because of a grade 3 neurotoxicity related to oxaliplatin. The patient was under medical surveillance for the following seven months without any clinical or morphological pejorative evolution.

In July 2010, the patient presented slight abdominal pain in the right side of the abdomen, revealing tumor progression without any recurrence of skin lesions. The CT-scan showed a 50% increase of pancreatic mass and liver metastases. The serum lipase was > 5000 UI/l.

As the neurological side effects had regressed to grade 1, the same regimen (FOLFOX 4) was started again. For the second time, a significant tumor response was objectified after only four courses. Therefore eight additional cycles were performed until December 2010. At this date the lipase level was 300 UI/l and the response was confirmed by CT-scan (). The chemotherapy was stopped because of neurotoxicity. In April 2011 (two years after the diagnosis of metastatic disease) the patient was asymptomatic with a good Performance Status (ECOG 0) and without evidence of disease progression.

Discussion and review of the literature

Pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma (ACC) is a rare tumor, which accounts for about 1% to 2% of all pancreatic cancers [Citation1,Citation2].

In the literature, few small-scale studies have examined ACC [Citation2–4]. In 2007, Hidehiko et al. reported the largest series of patients with ACC investigating the clinical characteristics, treatment and therapeutic outcomes of 115 patients registered in the Pancreatic Cancer Registry of the Japan Pancreas Society [Citation1].

Mean age at diagnosis is 60 years with a male preponderance (70%) [Citation1,Citation3]. Clinical presentation often includes abdominal pain, and others non-specific common signs are change in stools, abdominal palpable mass and jaundice [Citation3]. Lipase hypersecretion syndrome can be the initial presentation. High serum lipase level leads to a lypolytic process, with typical skin lesions of pancreatic panniculitis (Weber-Christian syndrome). Fat necrosis can affect periarticular and intramedullary fat, associated with arthralgia and fever [Citation5]. Contrary to ductal cell carcinoma, serum levels of CEA and CA19-9 are low in ACC [Citation1].

Surgical management is the only option that can lead to long-term survival [Citation1,Citation3]. By analogy with DCC, the resections techniques commonly performed are pancreatoduodenectomy and distal pancreatectomy. Katagami et al. reported a five-year survival rate of 43.9% with a median overall survival (OS) of 41 months in a series of 87 resected patients [Citation1]. On the other hand, the five-year survival rate without surgery was 0%.

Because of a low incidence of ACC compared to ductal cell carcinoma (DCC), it is difficult to reach a consensus on therapeutic outcomes in non-resectable disease. Data concerning treatment management are scarce especially for locally advanced tumor, recurrences and metastatic disease. Several chemotherapy regimens have been used and reported in the literature mainly as case reports. For locally advanced unresectable disease, chemoradiation is usually performed. 5FU, capecitabine or gemcitabine as radiosensitizing agents have been used [Citation3,Citation6,Citation7].

In metastatic ACC, few chemotherapy regimens have been associated with a stable disease or partial response [Citation3,Citation8–10] ().

Table I. Palliative chemotherapy for the treatment of pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma: Data from the literature.

Although it is difficult to draw any definitive conclusion from these case reports and small series, 5FU rather than gemcitabin seems a preferred drug in the palliative treatment of PACC.

In our patient, a progression under gemcitabin in first line was observed. We decided to use 5FU in second line. By analogy to PDCC we associated oxaliplatin to 5FU. Indeed, in PDCC, the interest of oxaliplatin is strongly suggested in association to gemcitabine [Citation11] or to 5FU and irinotecan [Citation12]. In this patient, the clinical and radiological benefit of the FOLFOX 4 regimen was impressive and the patient is still alive two years after the diagnosis of metastatic disease.

In conclusion, our case report and the review of the few published data suggest that the FOLFOX regimen could be a suitable treatment of PACC and deserve the use of this regimen, ideally prospectively to a better validation of the efficacy.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Kitagami H, Kondo S, Hirano S, . Acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas: Clinical analysis of 115 patients from Pancreatic Cancer Registry of Japan Pancreas Society. Pancreas 2007;35:42–6.

- Klimstra DS, Heffess CS, Oertel JE, . Acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas. A clinicopathologic study of 28 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1992;16:815–37.

- Holen KD, Klimstra DS, Hummer A, . Clinical characteristics and outcomes from an institutional series of acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas and related tumors. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:4673–8.

- Webb JN. Acinar cell neoplasms of the exocrine pancreas. J Clin Pathol 1977;30:103–12.

- Dahl PR, Su WP, Cullimore KC, . Pancreatic panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1995;33:413–7.

- Chen CP, Chao Y, Li CP, . Concurrent chemoradiation is effective in the treatment of alpha-fetoprotein-producing acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas: Report of a case. Pancreas 2001;22:326–9.

- Lee JL, Kim TW, Chang HM, . Locally advanced acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas successfully treated by capecitabine and concurrent radiotherapy: Report of two cases. Pancreas 2003;27:e18–22.

- Riechelmann RP, Hoff PM, Moron RA, . Acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas. Int J Gastrointest Cancer 2003;34:67–72.

- Sorscher SM. Metastatic acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas responding to gemcitabine, 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin therapy: A case report. Eur J Cancer Care 2009;18:318–9.

- Corbinais S, Egreteau J, Garin L, . [Acinous-cell carcinoma of a metastatic pancreas treated by chemotherapy]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2002;26:1180–1.

- Louvet C, Labianca R, Hammel P, . Gemcitabine in combination with oxaliplatin compared with gemcitabine alone in locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer: Results of a GERCOR and GISCAD phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:3509–16.

- Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, . FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. New Engl J Med 1011;364:1817–25.