To the Editor,

Autocrine secretion or aberrant levels of certain cytokines, such as interferon-γ (IFN-γ), may cause delayed apoptosis and extended survival of malignant cells [Citation1,Citation2]. We report the first case of aggressive primary testicular diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified (DLBCL, NOS), immunostained for IFN-γ and IFN-γ receptors (IFNGRs).

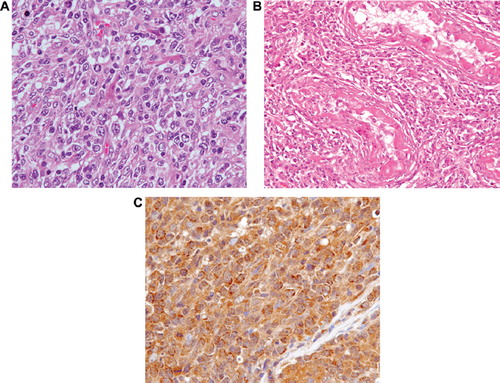

A 62-year-old man was admitted to our hospital with bilateral testicular swelling. Results of physical examination were remarkable, i.e. marked hepatosplenomegaly and lack of peripheral lymphadenopathy. Results of the blood analysis were as follows: white blood cell count 8.66 × 109/l; hemoglobin 143 g/l; platelet count 275 × 109/l; lactate dehydrogenase 218 IU/l; and C-reactive protein 1.90 mg/dl. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the testes showed low signal intensity on T1- and T2-weighted imaging and high signal intensity on Gd-enhanced T1-weighted imaging (). Whole body computed tomograhy (CT) revealed swelling of the para-aortic lymph nodes. The patient underwent right orchidectomy for evaluation of the diagnosis. Histologic examination showed a diffuse proliferation of large lymphoid cells that totally effaced normal architecture (). A portion of the seminiferous tubules remained, but lymphoma cells, which were positive for CD20, had infiltrated the remaining seminiferous tubules (). Immunohistochemical analysis of tumor cells showed them to be positive for CD20, CD79a, BCL6, and MUM1, but negative for CD3, CD5, CD10, CD30, BCL2, and TdT. The proliferation index assessed by Ki67 was 69%. Lymphoma cells were positive for IFN-γ (H145; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA, USA; ), IFN-γ receptor subunit 1 (IFNGR1), and IFN-γ receptor subunit 2 (IFNGR2).

Epstein-Barr-encoded RNA in situ hybridization was negative. Southern blotting revealed clonal rearrangement of the immunoglobulin heavy chain gene (IgH). Gene rearrangement of both IgH/MYC and IgH/BCL2 according to fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis was negative. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of DLBCL, NOS, non-germinal center B-cell-like (non-GCB) subtype, stage IVEA.

Figure 1. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of enlarged testes showing high signal intensity on Gd-enhanced T1-weighted imaging.

Figure 2. (A) Biopsy of the right testis showing diffuse proliferation of large lymphoid cells observed on histologic examination (hematoxylin-eosin stain (H&E); objective magnification × 40). (B) Biopsy of the right testis showing infiltration of lymphoma cells into the remaining seminiferous tubules (H&E, objective magnification × 20). (C) Abnormal cells positive for IFN-γ (objective magnification × 40).

Following treatment with six courses of R-CHOP therapy (a regimen of rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone) and irradiation (40 Gy) of the left testis, positron emission tomography (PET)/CT imaging still showed intense uptake at the left testis despite a reduction in testicular size. Immediately after therapy, an erythematous nodular eruption developed on the left hip. Pathological examination confirmed a skin infiltration of DLBCL, NOS, which was thought to be refractory to the previous therapy, and progressive disease was therefore diagnosed. Following salvage chemotherapy with R-ESHAP (a regimen of rituximab, etoposide, methylprednisolone, cytosine arabinoside, and platinum), the lymphoma lesions subsided.

Primary testicular lymphoma (PTL) is a very aggressive malignancy with a poor outcome confirmed for most patients with DLBCL, NOS. It has been suggested that PTL is protected by the blood–testis barrier, which comprises a structural barrier, an efflux-pump barrier, and an immunological barrier [Citation3,Citation4]. The normal function of the blood–testis barrier is to protect developing germ cells against harmful agents and immunological influences; this is necessary because many agents can disturb the delicate process of mitotic cell division. Although these protective properties are beneficial physiologically, some can act as an obstacle in chemotherapy [Citation4].

The involvement of several immunomodulatory mechanisms is required for the establishment and maintenance of tolerance towards germ cells within the testis in vivo, including passive, almost complete, segregation by barriers, regulation by paracrine immunosuppressive mediators, and active cell–cell interaction-mediated pathways. Sertoli cells are potentially capable of downregulating the local immune response [Citation5]. IFN-γ locally produced by macrophages, Leydig cells, and natural killer and T-cells during the inflammatory process determines the activation of two suppressive pathways mediated by Sertoli cells: (a) induction of the expression of B7-H1, which might effectively contribute to inhibition of immune responses by negatively interfering with CD8 + T-cell proliferation; and (b) induction of the expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II, which may mediate the increase of Tregs (regulatory T-cells) capable of suppressing other bystander T-cells [Citation5].

In addition, IFN-γ is a cytokine with growth-stimulating properties. Cellular responses to IFN-γ are mediated by the heterodimeric cell-surface receptor (IFNGR) of IFN-γ. IFNGR activates downstream signal transduction cascades, ultimately regulating gene expression. IFNGRs consist of two subunits: IFNGR1 (also known as the IFN-γ receptor-α chain) and INGR2 (also known as the IFN-γ receptor-β chain). The former is responsible for ligand binding and is required, but insufficient for signal transduction; the latter mainly plays a role in signaling of IFN-γ [Citation6]. IFN-γ induces c-Myc oncogene expression and promotes cell proliferation [Citation7]. c-Myc plays important roles in G1-S transition and cell proliferation. Furthermore, IFN-γ is the most important trigger for the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [Citation8]. ROS are known to play a central role in the initiation, promotion, and progression of cancer. Point mutations due to ROS may activate oncogenes, such as ras or inactivate tumor suppressor genes such as p53 and thereby enable cells otherwise prone to death or arrested growth to survive and proliferate [Citation9]. In addition, ROS may promote tumor growth via increased cytosolic Ca2 + , thus directly regulating transcription of genes such as the proto-oncogene c-fos, involved in cell proliferation [Citation10]. Apart from Ca2 + -mediated regulation, the direct effects of ROS on the transcription factor nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) (a member of the rel oncogene family) have also been described. B lymphocytes in chronic B-cell lymphocytic leukemia produce IFN-γ, which could prolong the life span of malignant cells via an autocrine mechanism in vitro [Citation1]. However, no reports exist of IFN-γ-producing DLBCL, NOS with expression of IFNGRs and which investigated the role of the autocrine mechanisms of IFN-γ in the extended survival of DLBCL, NOS.

To our knowledge, this is the first case report on primary testicular DLBCL, NOS immunostained for IFN-γ and IFNGRs that clearly demonstrates tumor cells expressing both IFN-γ and IFNGRs. IFN-γ, produced by tumor cells, might intestify the establishment and maintenance of tolerance towards lymphoma cells within the blood–testis barrier and also promote tumor cell growth via autocrine mechanisms, this being linked to an aggressive clinical course in some cases of primary testicular DLBCL, NOS.

Acknowledgements

This work was not supported by any grant-in-aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan. We have no personal or financial conflicts of interest related to the preparation and publication of this article.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Buschle M, Campana D, Carding SR, Richard C, Hoffbrand AV, Brenner MK. Interferon gamma inhibits apoptotic cell death in B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Exp Med 1993;177:213–8.

- Williams GT. Programmed cell death: Apoptosis and oncogenesis. Cell 1991;65:1097–8.

- Vitolo U, Ferreri AJ, Zucca E. Primary testicular lymphoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2008;65:183–9.

- Bart J, Groen HJ, van der Graaf WT, Hollema H, Hendrikse NH, Vaalburg W, . An oncological view on the blood-testis barrier. Lancet Oncol 2002;3:357–63.

- Dal Secco V, Riccioli A, Padula F, Ziparo E, Filippini A. Mouse Sertoli cells display phenotypical and functional traits of antigen-presenting cells in response to interferon gamma. Biol Reprod 2008;78:234–42.

- Stark GR, Kerr IM, Willams BR, Silverman RH, Schreiber RD. How cells respond to interferons. Annu Rev Biochem 1998;67:227–64.

- Asao H, Fu XY. Interferon-gamma has dual potentials in inhibiting or promoting cell proliferation. J Biol Chem 2000;275:867–74.

- Murr C, Fuith LC, Widner B, Wirleitner B, Baier-Bitterlich G, Fuchs D. Increased neopterin concentrations in patients with cancer: Indicator of oxidative stress? Anticancer Res 1999;19:1721–8.

- Bos JL. The ras gene family and human carcinogenesis. Mutat Res 1988;195:255–71.

- Maki A, Berezesky IK, Fargnoli J, Holbrook NJ, Trump BF. Role of [Ca2 + ]i in induction of c-fos, c-jun, and c-myc mRNA in rat PTE after oxidative stress. FASEB J 1992;6:919–24.