Abstract

Background. Breast cancer is the most common cancer among Danish women. Locally advanced breast cancer occurs in a relatively large proportion of all new primary breast cancer diagnoses and for unexplained reasons 20–30% of women with breast cancer wait more than eight weeks from the initial breast cancer symptom(s) before seeking medical advice. Material and methods. In this study, we performed a retrospective review of the medical records of patients referred to The Department of Breast Surgery, Rigshospitalet in Copenhagen in the period between 2006 and 2011, to characterize women presenting with breast cancer either larger than 5 cm or locally advanced breast cancer/inoperable breast cancer (LABC/IOBC). The aim of the study was to characterize these women concerning age, social status, co-morbidity, defined anamnestic parameters concerning breast history and delay in seeking medical advice, to explore whether common traits among these parameters could be identified which could account for the late diagnosis. Results. We identified 157 cases. The median age of our cohort was 67 years (range 30–98) and did not differ from all women with breast cancer, but with a high risk of severe medical co-morbidity, psychiatric co-morbidity or dementia. However, 42% did not reveal any history of a psychiatric or somatic co-morbidity did not take psychoactive drugs and had no previous benign breast disorder. They were living in their own homes, were married, did not suffer from dementia, could have a first-degree relative with a history of breast cancer, but still presented with breast cancer characterized as LABC/IOBC, without any apparent reason. Among these 42%, more than half had neglected their obvious symptoms of breast cancer.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among Danish women. Earlier detection and major improvements in the treatment have led to a decrease in mortality over the last 25 years [Citation1].

Breast cancer is extremely exposed in the press, exemplified by the pink ribbon campaign, and the general awareness of the disease can hardly be increased. Population based mammography screening has been offered to women in the catchment area of the department aged 50–69 years in the study period. Despite this focus on the disease some women still present with advanced disease with obvious symptoms that have presumably been neglected over a longer time period.

Delay in diagnostic assessment can be divided into patient and system delay. Patient delay is late contact to the medical system, whereas system delay is prolonged time from first contact with a medical caregiver to initiation of therapy. Any kind of delay can result in an impaired prognosis. Afzelius et al. have shown that women with advanced disease, unsurprisingly, have the shortest system delay [Citation2].

Locally advanced breast (LABC) is defined as large primary tumors and inoperable breast cancer (IOBC) as advanced axillary/periclavicular lymph node involvement. These patients are candidates for primary systemic therapy. This is reported to occur in 10–15% of all new primary breast cancer diagnoses [Citation3]. For reasons that are still not clarified, 20–30% of women with breast cancer wait more than eight weeks from the initial symptom(s) until they seek clinical assessment [Citation4,Citation5]. Prognosis is stage-dependent, which implies that early contact to the health care system and early diagnosis and treatment is a prerequisite for improving prognosis. Richards et al. reported a 12–19% decrease in five-year survival in those women with delays of three months or more versus those with shorter time to diagnosis [Citation6].

The following factors have been cited as causes of patient delay: poor access to health care, lack of preventive health care habits, increasing age, having childcare/elder care obligations, notion that the symptoms are benign, poor education, misperception of risk, embarrassment, fear of chemotherapy and breast loss, concern about being a hypochondriac and pessimist about survival [Citation4,Citation5,Citation7,Citation8].

Understanding the factors that influence the delay is important for the development of strategies to shorten delays.

In this study, we conducted a retrospective review of medical records to characterize women presenting with LABC/IOBC in order to characterize women who have neglected obvious symptoms of breast cancer.

Material and methods

Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative group, DBCG, was initiated in 1977 and designed primarily to provide guidelines for treatment of breast cancer patients, to conduct nationwide trials of adjuvant therapy, and to evaluate treatment programs. Primary clinical and histopathological data including tumor stage have been registered by the DBCG based on specific forms submitted by the department of surgery, pathology and oncology in Denmark. DBCG is described in detail elsewhere [Citation9].

Included in the present study were women registered in DBCG with tumors either larger then 5 cm and/or “primary unresectable or loco-regional advanced breast cancer” treated at Rigshospitalet from 2006 to 2011.

The review of surgical as well as oncological records was focused on family history of breast cancer, family history of others malignancies, co-morbidity, use of psychoactive drugs, social status, previous benign breast diseases and age. Data were retrieved by a M.D. in surgical training and a medical student. All the data was double checked to avoid errors in data collection.

Results

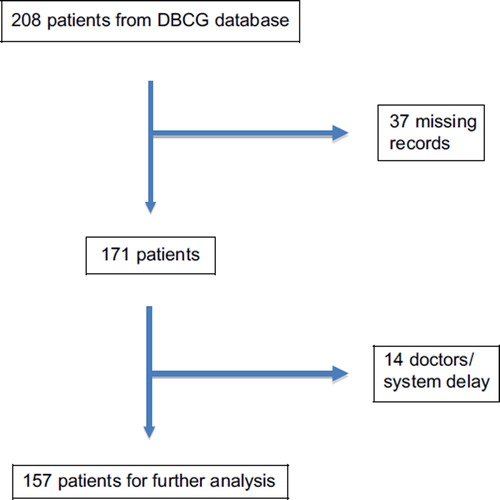

Two hundred and eight patients with LABC/IOBC were identified from the DBCG database. One hundred and seventy-one records were retrieved. Fourteen patients were excluded because of doctor's delay, tumors in a large breast with no obvious clinical signs at presentation, or delay due to pregnancy, leaving 157 patients for further analysis (see ). Patient characteristics are shown in and . Eighty-nine patients had tumors larger then 5 cm. Forty-four patients had “unresectable or loco- regional advanced breast cancer”. Forty-two patients had breast cancer with distant metastases. Some patients were affected both by tumors larger then 5 cm, unresectable disease and distant metastases (See ).

Table I. Distribution of 157 women presenting with locally advanced or inoperable primary breast cancer according to 2006–2011 at Department of Breast Surgery, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Table II. Characteristics of 157 women presenting with locally advanced or inoperable primary breast cancer 2006–2011 at Department of Breast Surgery, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Median age was 67 years (range 30–98), and 72.9% of the enrolled patients were older than 60 years. An ulcerated breast cancer was found in 20.3%, which was defined as a tumor involving skin with ulceration. 7% had inflammatory breast cancer characterized by edematous, indurated and erythematous skin changes.

A history of benign tumors or abscesses occurred in 3.2% of the patients.

Anxiety, depression, schizophrenia or bipolar disorders were noted among 14.6% and 17.6% were users of antipsychotics, antidepressants or lithium. 7.6% of patients were reported with dementia and 12.1% lived in nursing homes, 58.6% lived alone, either as widows, divorcees or singles. 17.1% had a first-degree relative with breast cancer either mother, sister or daughter. 5.7% had a first-degree relative with another malignant disease.

3% of women were of non-Danish ethnic origin and were not Danish speaking.

Co-morbidity was not scored systematically in the medical records. The noted index was derived from descriptions in the records and anesthetic charts: 31.8% scored ≥ 3 on Charlson’s age-adjusted co-morbidity index and 15.3% scored ≥ 5.

Patient's delay was only noted in 32% (n = 50) of the records.

In 42% of the women (n = 66) none of the above mentioned characteristics could be found. When this group of patients was examined in detail, it was seen that 37 patients from this group had one or more of the following characteristics: a documented delay of three months or more, inflammatory breast cancer, ulcerated breast cancer, breast cancer with other clinical skin involvement.

The remaining 29 patients in this group showed the following characteristics: no delay was documented, 28 patients had tumors > 5 cm and one patient had a tumor measuring 3.5 cm but with systemic disease (T2NXM1). Hence, among these patients no further information on concurrent causes of the advanced stage of disease could be found in the records.

Discussion

The median age for all women with breast cancer in Denmark is 66 years [Citation1]. This means that the median age of women in the present group is not different from the average.

Taking all women operated for breast cancer at Rigshospitalet from 1994–2003, 88.4% scored 0 on Charlson's index, 7.4% scored > 1 and 4.2% scored > 2 on Charlson's index [Citation10]. A score of ≥ 3 on Charlson’s index is defined as severe co-morbidity. Patients with a score ≥ 5 have a close to 100% one-year mortality [Citation11]. Our results have shown that women with LABC/IOBC are extensively characterized by somatic co-morbidity. An obvious explanation for the advanced stage of disease among these women could be, that the other somatic symptoms overshadow the symptoms from the breast tumor, or that the patients have many concerns already and cannot cope with various new symptoms.

Carlsen et al. have shown that women with a previous diagnosis of depression or schizophrenia had significantly higher risk for breast cancer than women without psychiatric disorders [Citation10]. Others have not been able to confirm this observation [Citation12]. Among all Danish women with breast cancer during the years 1994–2003, 4.5% had a psychiatric diagnosis [Citation10]. Hence, in our group of women with LABC/IOBC cases, there is an increased representation of psychiatric disorders.

Among all women with breast cancer in Denmark 26.3% lived alone at the time of diagnosis compared to 58.6% in the present study [Citation10]. It has been shown that the risk of breast cancer is increased for singles and divorced women and is thus in accordance with our observations, where the rate of advanced disease is twice of the normal population [Citation10].

We had hypothesized that women with a first-degree relative with breast cancer would probably seek the doctor early at signs of breast disease due to increased awareness of the disease. Our data, however, reveals that nearly one in five women with LABC/IOBC have a first-degree relative with breast cancer. Others had similar observations [Citation13,Citation14]. A possible explanation could be defense mechanisms such as denial or bad experiences with breast cancer. In an overview analysis of 52 case-control studies concerning 58 209 breast cancer cases and 101 986 controls, 12.9% of all women with breast cancer have a first-degree relative with the same disease, whereas the percentage in our data is 17.1% [Citation15].

Most estimates of patient delay use the definition first proposed in 1935 by Pack and Gallo, a time period of three months or more from symptom debut to initial medical examination [Citation16]. Our calculated delay () is consistent with the delay reported in another study [Citation6].

If a woman previously has had a benign breast disease, one could imagine that in case of a new lump in the breast, she might interpret this as benign and thus postpone the visit to the doctor. This is described in the literature, but is not seen in our material, since only 3% of women with LABC/IOBC report previously benign breast disorder [Citation17,Citation18].

It is often caregivers, relatives, or a general practitioner that accidentally discover the tumor among women with dementia, and delay can therefore reach several years.

It is therefore not surprising that in a group of women with LABC/IOBC, the frequency of dementia is seven-fold higher than in the normal population, as data from DBCG shows that approximately 1% of women with breast cancer are characterized by dementia [Citation19].

A large Danish inventory has shown that the risk of developing breast cancer among women from non-Western countries is lower than ethnic Danish women [Citation10]. Women of different ethnic origin with breast cancer in Denmark represent 4.2% of the total [Citation10]. In our study group, we found that only four women of different ethnic origin (both western and non-western countries) had LABC/IOBC, equivalent to approximately 3%. We can thus conclude that women of different ethnic origin are not overrepresented with LABC/IOBC in this small study. Compared to this, African-American women and Latino women have shown to be diagnosed with more advanced stage disease compared to Caucasian women in US population, but this most likely reflects inequalities in the American health care system [Citation20–22].

In the present study, we have confirmed that women with LABC/IOBC are generally more likely to suffer from somatic and psychiatric co-morbidity and more often live alone. However, we found no trend towards elder age or other ethnic origin.

An interesting observation is that 37 women (= 23.6%) who had obvious symptoms of breast cancer still waited at least three months before they went to the doctor. They did not reveal any diagnosis of a psychiatric or somatic co-morbidity; did not have a consumption of psychotropic drugs, no previous benign breast disorder, they were living in their own homes, were married, did not suffer from dementia and could have a first-degree relative with a history of breast cancer. It is obvious that denial must play a role in their behavior, which in other studies also has been described as the primary reason why women neglect symptoms or refuse treatment [Citation23,Citation24].

Based on our data, the obvious question is how public campaigns should be designed to improve early detection and thus reducing the frequency of neglected cases.

It implies a greater awareness by general practitioners, by caregivers in the psychiatry and in home care for an outreach effort to detect these cases as early as possible so that proper treatment can be initiated. However, such initiatives would hardly reduce the group in which we found no obvious reasons for the neglect. Prospective studies to examine these patients closer would be desirable, but accrual would probably be slow.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- From NORDCAN. Nordcan is a database with information and data regarding incidence, mortality rates, prevalence and survival rates for 41 cancers in the nordic countries (www.dep.iarc.fr/NORDCAN/DK/frame.asp).

- Afzelius P, Zedeler K, Sommer H, Mouridsen HT, Blichert-Toft M. Patient's and doctor's delay in primary breast cancer. Prognostic implications. Acta Oncol 1994;33:345–51.

- Kaufman M, Hortobagyi GN, Goldhirsch A, Scholl S, Makris A, Valagussa P, . Recommendations from an international expert panel on the use of neoadjuvant (primary) systemic treatment of operable breast cancer: An update. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:1940–9.

- Caplan L, Helzlsouer K. Delay in breast cancer: A review of the literature. Public Health Rev 1992–1993;20:187–214.

- Nosarti C, Crayford T, Roberts JV, Elias E, McKenzie K, David AS. Delay in presentation of symptomatic referrals to a breast clinic: Patient and system factors. Br J Cancer 2000;82:742–8.

- Richards MA, Westcombe AM, Love SB, Littlejohns P, Ramirez AJ. Influence of delay on survival in patients with breast cancer: A systematic review. Lancet 1999;353:1119–26.

- Arndt V, Stürmer T, Stegmaier C, Ziegler H, Dhom G, Brenner H. Patient delay and stage of diagnosis among breast cancer patients in Germany – a population based study. Br J Cancer 2002;86:1034–40.

- Burgess C, Hunter MS, Ramirez AJ. A qualitative study of delay among women reporting symptoms of breast cancer. Br J Gen Pract 2001;51:967–71.

- Andersen KW, Mouridsen HT. Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group (DBCG). A description of the register of the nation-wide programme for primary breast cancer. Acta Oncol 1988;27:627–47.

- Carlsen K, Høybye MT, Dalton SO, Tjønneland A. Social inequality and incidence of and survival from breast cancer in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994–2003. Eur J Cancer 2008;44:1996–2002.

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chron Dis 1987;40:373–83.

- Bushe CJ, Bradley AJ, Wildgust HJ, Hodgson RE. Schizophrenia and breast cancer incidence – A systematic review of clinical studies. Schizophr Res 2009;114:6–16.

- Meechan G, Collins J, Petrie KJ. The relationship of symptoms and psychological factors to delay in seeking medical care for breast symptoms. Prev Med 2003;36:374–8.

- Meechan G, Collins J, Petrie K. Delay in seeking medical care for self-detected breast symptoms in New Zealand women. N Z Med J 2002;115:U257.

- Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Familial breast cancer: Collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 52 epidemiological studies including 58,209 women with breast cancer and 101,986 women without the disease. Lancet 2001;358:1389–99.

- Pack GT, Gallo JS. The culpability for delay in the treatment of cancer. Am J Cancer 1938;33:443–62.

- Adam SA, Horner JK, Vessey MP. Delay in treatment for breast cancer. Community Med 1980;2:195–201.

- Gould J, Fitzgerald B, Fergus K, Clemons M, Baig F. Why women delay seeking assistance for locally advanced breast cancer. Can Oncol Nurs J 2010;20:23–9.

- From DBCG. In the DBCG register it is recorded if the patient suffers from dementia or other diseases.

- Hunter CP, Redmond CK, Chen VW, Austin DF, Greenberg RS, Correa P, . Breast cancer factors associated with stage at diagnosis in black and white women. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993;85:1129–37.

- Coates R, Bransfield D, Wesley M, Hankey B, Eley JW, Greenberg RS, . Differences between black and white women with breast cancer in time from symptom recognition to medical consultation. J Natl Cancer Inst 1992;84:938–50.

- Zaloznik AJ. Breast cancer stage at diagnosis: Caucasians versus Afro-Americans. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1995;34:195–9.

- Weinman S, Taplin SH, Gilbert J, Beverly RK, Geiger AM, Yood MU, . Characteristics of women refusing follow-up for tests or symptoms suggestive of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2005;35:33–8.

- Mohamed IE, Skeel WK, Tamburrino M, Wryobeck J, Carter S. Understanding locally advanced breast cancer: What influences a woman's decision to delay treatment? Prev Med 2005;41:399–405.