Abstract

Background. There are no established treatments for cachexia. Recently it has been suggested that the evidence for non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID) treatment is sufficient to support its regular clinical use. Primary objective in this systematic review was to assess efficacy and safety of NSAID treatment in improving body weight and muscle mass in patients with cancer cachexia. Secondary objectives were to assess whether this treatment could improve other cachexia domains such as anorexia and food intake, catabolic drive and function. Material and methods. A systematic literature review of PubMed, EMBASE and Cochrane Central register of controlled trials database was carried out using both text words and MeSH/EMTREE terms. Results. Thirteen studies were included; all but two trials showed either improvement or stabilization in weight or lean body mass. Seven studies were without a comparator. Studies are generally small and a few are methodologically flawed, often due to multiple outcomes with excess risk of false positives. Conclusion. NSAIDs may improve weight in cancer patients with cachexia, and there is some evidence on effect on physical performance, self-reported quality of life and inflammatory parameters. Evidence is too frail to recommend NSAID for cachexia outside clinical trials. This is supported by the known side effects of NSAIDs, even though the reviewed literature report almost negligible toxicity.

Cancer cachexia is a multifactorial syndrome affecting almost 50% of all cancer patients [Citation1]. It is characterized by skeletal muscle wasting with or without loss of fat mass [Citation2] and is often associated with psychological distress, fatigue and deterioration in physical function.

A new international consensus classifies cachexia into early cachexia, cachexia and refractory cachexia where diagnostic criteria include weight loss but moreover, consider sarcopenia or low body mass index (BMI) [Citation2]. The consensus states that characterization of cachectic patients should consider four domains, namely anorexia and food intake, catabolic drive, muscle strength and physical/ psychosocial function.

In concordance with the cachexia definition most studies have stabilization or gain of body weight as an outcome. Body weight is, however, a crude outcome that constitutes of fat mass, body water and lean body mass (LBM). The measurement of LBM is advocated, but there is no agreement on methodology.

At present, there are no established treatments for cachexia, and clinicians consequently find its management challenging. Only two drugs are widely prescribed, namely progestines and corticosteroids [Citation3]. Unfortunately neither of these drugs has positive effects on muscle loss, and their side effects do not make them applicable for long-term use.

The pathogenesis of cancer cachexia is complex and not fully understood. Inflammation is important and several pro-inflammatory cytokines are involved, either as the host's inflammatory response to the tumor, or as a result of direct release by tumor itself [Citation4]. Subsequent systemic inflammation initiates alterations in metabolism through an IL-6 dependent mechanism, but molecules like IL-1β, IL-2, IL-8, TNF-α, and IFN-γ are probably also of significance [Citation5]. Inflammation has numerous facilitatory effects on development of the cachexia syndrome. For instance muscle growth may be suppressed due to up-regulation of Myostatin by increased levels of TNF-α [Citation4] and anorexia may be induced through activation of the melanocortin pathway by cytokines such as IL-1 [Citation6].

Aspirin and related NSAIDs such as ibuprofen are non-selective blockers of the cyclooxygenase pathway and inhibit production of prostaglandins that cause inflammation and pain (COX-2 pathway). These drugs also block formation of thromboxane A2 (TXA2) in platelets and hence prevent platelet aggregation. NSAIDs can increase the risk of gastrointestinal hemorrhage via blockade of the COX-1 pathway which provides mucosa–protective prostaglandins. Based on growing knowledge that inflammation is a main driver of cachexia, the number of anti-inflammatory drug trials in cachexia is increasing. Several authors claim the evidence for NSAID treatment in cachexia is now sufficient to be prescribed for regular use [Citation7–9] or to apply in both treatment and best clinical practice arms in randomized studies [Citation10]. Alternatively some argue that NSAID use is less documented in cancer patients than in the general population, and that side effects are likely to be increased [Citation11]. As COX-2 often are up-regulated in cancer and have been associated with carcinogenesis, tumor growth and metastasis [Citation12], COX-2 selective drugs, such as celecoxib, have lately been the drug of choice both in humans and animals studies. However, the anti-cancer effects of non–selective NSAIDs should not be forgotten.

Aspirin seems to be an important chemopreventive drug where two recent large scale studies have provided additional evidence that low dose aspirin reduces incidence of cancer, death from cancer and cancer metastasis [Citation13,Citation14].

It is essential to understand the strengths, discrepancies, and limitations in previously published literature when aiming to proceed with the development of treatment regimens or new study protocols.

We therefore conducted a systematic literary review to assess efficacy, effectiveness and safety of NSAIDs in the management of cancer cachexia.

Method

Studies with adult patients with cancer cachexia that evaluated efficacy and/or side effects of NSAID treatment were included. Studies were excluded if the indication for NSAID treatment was not to treat cancer cachexia.

Weight loss was the primary outcome (measured in kilograms or pounds both in LBM, total body mass and fat mass). Secondary outcomes were: anorexia and food intake, muscle strength, catabolic drive and finally function and psychosocial effect. In order to gather all relevant literature and obtain enough information on side effects this review included randomized controlled trials (RCTs), quasi-RCT, cohort studies, pre-post study design and case control studies. Case series with 10 or less participants, qualitative studies and studies with intervention lasting less than 14 days were not included. Only studies published full-text in peer-review journals were included. No limits regarding route of drug administration or language was applied.

The literature search was conducted on PubMed (includes MEDLINE), Embase (through OvidSP) and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), over a time frame ranging from each database set-up date to 4 February 2012. The search strategy for the Embase database is reported in Table (Search strategies for PubMed and Cochrane, available at Supplementary material available online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2012.724536).

Appropriately revised strategies were developed for each database; a hand search of the references list of selected papers was also performed. All identified papers were collated into a computer-based reference management system (EndNote x5) and screened for duplicate studies. The list of studies was then separately screened and assessed for inclusion by two authors (TSS and DB) using title and abstract. Disagreements were resolved by discussion and reasons for excluding trials were reported.

Description of study quality and content

The content of each included study was then analyzed reading full text articles using methodological indications from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [Citation15], and summarized according to a standardized form. A pragmatic quality assessment model based on the Cochrane guidelines was applied as the review included non-RCTs.

Results

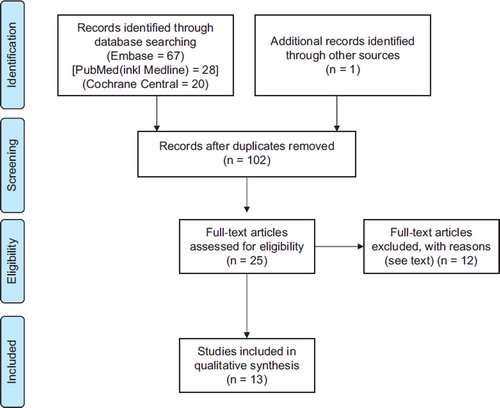

The literature search retrieved 101 papers (). One study was added after a hand search of reference lists. Twenty-five papers were selected for full-text examination after screening of abstracts.

Twelve papers were excluded; six where the aim was not to treat or include cachectic patients [Citation16–21], two as intervention only lasted three and seven days [Citation22,Citation23], three studies where the patients were reported in prior publications [Citation24–26] and finally one since ≤ 1/3 of the patients received NSAIDs [Citation8]. There was complete agreement between the authors on which papers to include.

The present review is thus based on 13 studies. Six studies investigated NSAIDs with a comparator and seven without. In three RCTs, NSAIDs were included in both arms and the between arms effect could not be assessed, but as the trials had pre-post analysis they were included as non-comparative studies [Citation7].

Four studies looked at indomethacin [Citation9,Citation27–29], seven studies looked at celecoxib [Citation7,Citation30–35] and two studies looked at ibuprofen [Citation36,Citation37].

Effect of NSAID treatment

Six of 13 studies were comparative trials where one of the arms included NSAID treatment; five of these were randomized and one was a retrospective case control study [Citation29]. Three studies looked at the NSAID effect alone [Citation27,Citation29,Citation30] and three looked at combination regimes with Megace acetate (MA) [Citation37], fish oil [Citation35] and one with the combination of L-Carnitine, antioxidants and MA [Citation31] ().

Table I. Comparative studies.

Lundholm (1994) [Citation27]. One hundred and thirty–five patients with mixed advanced cancer without concomitant cancer treatment were randomized to three groups: placebo, prednisolone or indomethacin. No significant improvement in body weight, C-reactive protein (CRP), fatigue or handgrip strength was demonstrated when comparing placebo against indomethacin during the observational period that lasted until death. The study did, however, indicate significantly increase the Karnofsky score (KPS) (66 ± 3 vs. 75 ± 2; p =0.03) and survival (250 ±28 days to 510 ±28 days; p< 0.05) in indomethacin treated patients. Due to the impression that both palliation and survival was improved compared with placebo, the trial was closed early.

McMillan (1999) [Citation37]. Seventy-three patients with advanced gastrointestinal cancer and more than two months expected survival were randomized to 12 weeks treatment with either MA/placebo or MA/ibuprofen. Mainly due to disease progression, this trial had large dropout rates. The trial demonstrated significant weight improvement in patients treated with ibuprofen (6 weeks: Δ 2.5 kg; p< 0.01/12 weeks: Δ 5.1 kg; p< 0.001). There was significant decrease in numbers of patients with CRP > 5 in the ibuprofen/MA group (decrease in 8 of 10 patients vs. 0 of 13 in placebo group). Both groups had significant improvement in appetite (EORTC QLQ-C30) from baseline (p< 0.05), but there were no differences between the groups in four to six weeks. At 12 weeks, quality of life scores (EuroQol-EQ-5D) were significantly better in the ibuprofen treated group (p< 0.05) (effect size not reported).

Lundholm (2004) [Citation29]. One hundred and fifty–one cancer patients treated with indomethacin were matched with 145 cancer controls without NSAID treatment in this retrospective case-control analysis. The study demonstrated that patients receiving indomethacin had significantly greater body weight during follow-up (Δ 5.1 kg; p< 0.05), principally due to more body fat (p < 0.005). LBM was the same in both groups. Indomethacin treated patients had significantly higher food intake (1890 vs. 1679 Kcal), and lower CRP (31 ±2 vs. 61 ±4 mg/l) and resting energy expenditure (REE) (22.2 ±0.2 vs. 23.2 ± 0.2 kcal/kg/day). There were no differences in survival.

Cercetti (2007) [Citation35]. Twenty-two patients with advanced and progressive lung cancer were randomized to either fish oil/placebo or fish oil/celecoxib. Both groups received oral food supplementation. There was a significant difference between the groups, in change from baseline, concerning body weight (Δ 2.9 kg; p=0.05), handgrip strength (3.12 vs. 1.16; p= 0.002) and CRP (26.7 vs. 221.3; p=0.005) in favor of the group receiving celecoxib. There were no differences in change from fatigue or appetite between the groups.

Lai (2008) [Citation30]. Eleven patients with head and neck cancer/gastrointestinal cancer were randomized to three weeks treatment with either placebo or celecoxib while awaiting start of anti-cancer treatment. The celecoxib group demonstrated improvement in weight (Δ 2.3 kg; p=0.05) and Functional Assessment of Anorexia/Cachexia Therapy score (FACCT) (p= 0.05). There were no significant differences in KPS, cytokine levels (IL-6, IL-6HS, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-8, TNF-α, IFN-γ) or CRP between the groups.

Maccio (2011) [Citation31] One hundred and forty-four patients with advanced gynecological tumors were randomized to either the combination of MA, carnitine, celecoxib and antioxidants or MA alone. All patients received psychosocial counseling. A significant (p= 0.032) increase in LBM in favor of the combination regimen was reported (Δ 4.65 kg; 95% CI + 8.8–0.4 kg). The combination arm also demonstrated significantly improved REE (1166–> 1042 vs. 1157–> 1312; p=0.046), Global Quality of Life (EORTC QLQ C-30: 53.8–> 61.3 vs. 57–> 61.1; p= 0.042) and Fatigue (MFSI-SF score: 26.3–> 19.9 vs. 22.6–> 23.5; p=0.049). Concerning secondary outcomes there were no significant improvements in grip strength, appetite or ECOG PS. With regard to catabolic factors, there were no significant differences between the groups in Glasgow Prognostic Score (GPS) (p = 0.24) or CRP (p= 0.056), but a significant improvement in circulatory levels of IL-6 (p =0.003), TNF-α (p = 0.04), leptin (p = 0.048) and reactive oxygen species (p= 0.037).

The effect sizes for outcomes in trials without NSAID control are changes from baseline to post-treatment. The results from these seven trials are presented in Supplementary to be found online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2012.724536.

Summary of findings

Patients included in most trials were heterogeneous, and reflecting both cancer and cachexia incidence, most patients had advanced gastrointestinal or lung cancer. Only two trials included patients with early cachexia/cachexia, seven with cachexia, and four with late cachexia.

The numbers of outcomes ranged from two to 22, and there were considerable diversities in the outcomes reported. For example weight/body composition was assessed by change in total body weight, body fat and/or LMB [measured by computed tomography (CT)-scans, bio impedance or Dual Energy X-ray (DEXA)]. Other weight outcomes were rate of loss of body weight, BMI, mid upper arm circumference and the number who lost or gained weight. Anorexia was measured by VAS, NRS or EORTC QLQ-C30. Catabolism was measured mainly by REE, plasma CRP/cytokine concentrations or cancer disease progression.

Duration of treatment ranged from two to 125 weeks, the most frequent being 16 weeks [Citation7,Citation31–33].

To summarize the comparative trials, the median improvement in body weight for patients on NSAIDs were in one trial 2.5 kg at six weeks and 5.1 kg at 12 weeks [Citation37], another study showed a difference of 2.9 kg at six weeks [Citation35], the third a difference of 2.3 kg at three weeks [Citation30]. A fourth study followed the patients to death, approximately 4–72 weeks, and described a mean weight difference between the patients of 5.1 kg, mainly explained by body fat, and no significant difference in LBM. Finally one study did not investigate the effect on total body weight, but reported a mean difference in LBM after 16 weeks of 4.65 kg [Citation31]. One study did not present an improvement in body weight after NSAID use [Citation27]. All studies reported improvements in several other cachexia domains, but there were also outcomes that were statistically or clinically non-significant.

In the studies where it was necessary to address pre-post analysis all but one showed either improvements or stabilizations an in body weight or LBM. For other cachexia domains there was most evidence for an effect on physical performance status, Global Quality of Life (QoL) and inflammation.

Side effects

Nine trials reported negligible or no specified side effects of NSAIDs. One trial including 74 patients with advanced cachexia reported one (fatal) gastrointestinal bleed in group 1 (MA) vs. two non–fatal bleedings in group 2 (MA+ ibuprofen) [Citation37]. Furthermore, there was one patient in group 1 and two patients in group 2 who experienced a venous thrombosis, a well-recognized side effect of MA and probably not related to NSAID use in this trial The same study reported a significant increase in water retention in the MA/ibuprofen group and ascites was present in two patients in group 1 vs. three in group 2. Another trial reported grade 1 or 2 epigastric pain in one of 24 patients [Citation33]. One other study reported water retention (in four of 151 patients). The same study also described significant elevation of creatinine and systolic blood pressure in the group that used indomethacin [Citation29]. Four other trials reported no water retention; the rest of the studies did not address this specifically.

Quality of evidence

The quality of the included studies is summarized in Supplementary Table II to be found online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2012.724536. Many studies were carried out on a small number of patients. Six trials had a NSAID comparator, the rest did not. Some studies had significant sample attrition, and a few did not clearly report the number of dropouts or side effects. The outcomes in the different studies were often numerous, but only a few trials took steps to mitigate the multiplicity issues. Studies often performed intention-to-treat analyses and no trials were industry sponsored. Only one study closed early for benefit [Citation28].

A meta-analysis was inappropriate: half of the studies were without controls, three different NSAIDs were administrated with different dosages, there were various follow-up periods and a mixture of outcomes.

Discussion

This systematic literature review identified 13 trials that reported outcomes of NSAID treatment in cancer cachexia patients. Taken together, these provide evidence that NSAIDs have an effect since most trials demonstrate improvements in both weight/LBM (from 2.5 kg after six weeks and 5.1 kg after 12 weeks) and other cachexia domains such as global quality of life or functional level.

Clinical significant outcomes

All 13 studies report significant changes in one or more of the proposed domains. It is important to acknowledge that several indicators can describe these domains, and that gold standard indices have yet to be established. Moreover, it may be premature to conclude whether improvements achieved are clinically significant. For some items such as the EORTC QLQ-C30 there are agreements on changes necessary to establish clinical benefit [Citation38]. Conversely, several studies have used a 2 kg difference in body weight as a clinically important effect size, but the rationale for this threshold is not stated. There is also little evidence on the clinical benefits of gaining LBM in cancer patients, or how much LBM you need to gain in order to obtain such benefits. Considering physical performance, the clinical significance of most tests is predominantly unresolved in heterogeneous cancer patients. For instance, an increase of 50 m in a 6 minutes’ walk test has demonstrated associated with a 13% reduction of mortality in metastatic non-small cell lung cancer, but the test is not an independent prognostic factor for recurrent malignant glioma [Citation39]. Likewise is it not known what a reduction in inflammatory indices like IL-6 and CRP imply, or how much they should be reduced by in order to achieve a clinically significant goal. However, it is likely that parallel and consistent changes in the four cachexia domains are of importance.

Side effects

NSAIDs are frequently used in the general population, and may increase further due to an aging population that use NSAIDs for musculoskeletal pains or prevention of cardiovascular disease. Different NSAIDs have been on the market for many years. In fact as the first NSAID, salicylic acid, was chemically synthesized as early as 1860, side effects that accompanying this class of drug are well established. However, risks of adverse events may not be extrapolated readily to patients with cancer cachexia. The most significant side effects are gastrointestinal ulcers/hemorrhage and cardiac events. The risk of these complications varies and is often relatively small, but cannot be neglected [Citation40]. In the present review a total of 1128 patients were included in the different trials, 784 of these patients were treated with NSAIDs over a time frame ranging from four to 120 weeks. Most studies reported that side effects were negligible or comparable with the placebo group. Patients with cardiac disease were excluded from the majority of trials investigating selective COX-2 inhibitors. The inhibition of prostacyclin synthesis can induce fluid retention, and result in a weight gain of 0.5–1.0 kg [Citation41]. Two reviewed trials reported an increase in total body water, and concluded that some of the increase in body weight is due to water retention. On the other hand, another four trials specifically pointed out that the patients experienced no increase in total body water. In addition, for the 10 trials that assessed LBM seven reported improvements in the outcome (two of the seven reported however only a trend towards increased LBM) [Citation30,Citation34] and one in body fat. Accordingly, it is not likely that the observed gain or stabilization of weight in the reviewed studies is attributed to an increase in body water alone.

Limitations of the review

Even though the overall results imply a significant effect of NSAID on cachexia outcomes, the present literature has several limitations. Many studies are small but explore a large number of outcomes without adequate statistical adjustment of significant levels, thus risking of both false negative and false positive findings.

Seven studies were without comparator. Some of these studies included only cachectic patients where no cancer treatment was available and further decline in weight and function seems inevitable. Improvement or stabilization from baseline can consequently signify a treatment effect. In trials where patients received chemotherapy and some had stable disease or even a partial response, it is more difficult to estimate what the outcomes would have been without the NSAID intervention. The results from trials without comparator must be interpreted with caution (as with small RCTs).

An international consensus has concluded that cachexia is a trajectory from early to late cachexia, but which variables to apply when classifying the patients into the different cachexia stages is not established [Citation2]. The staging in and Supplementary (Supplementary Table I to be found online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2012.724536) is consequently only tentative, cachexia patients may require different treatment strategies according to where they are in the cachexia trajectory. In early cachexia one would try to prevent further weight loss, in cachexia the goal is to improve or stabilize weight, while the focus in refractory cachexia is to alleviate distressing symptoms as it is probably impossible to regain muscle mass [Citation2]. In the 13 publications reviewed, there are no obvious consistent differences in effect sizes observed at different cachexia stages.

In addition to patient selection and timing, duration of the intervention is important. If patients are treated for a long time, the effects of a non-curable and progressive cancer might eventually overshadow both effects and side effects of the study drug. Conversely, if the patient is treated for only a few weeks the gaining of a detectable amount of muscle mass seems unlikely. The duration of treatment in the studies in this review vary from three to 125 weeks, which makes comparing the NSAID effect difficult.

The diversity of patients included, differences in NSAID regimens, and variable treatment durations limit across-study comparisons and make it challenging to reach conclusions on the effect and effect size of NSAIDs in cachexia. In addition there is a lack of robust clinically important outcome variables. As a consequence, most secondary outcomes of the trials are presented in and Supplementary (Supplementary Table I to be found online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2012.724536) and are not discussed further.

NSAID use in the cancer population

As NSAID is commonly used in a general population up to 20% of cancer patients are already on NSAID treatment at the time of diagnosis. Interaction on tumor growth and chemotherapy thus needs very careful consideration. Clearly the best way to control cachexia is to control cancer progression.

In animals several different NSAIDs have demonstrated impressing effect on tumor growth [Citation42–44]. For humans there are, however, only conflicting data both for increased risk of cancer [Citation45], prevention of cancer [Citation46] and the effect of concomitant NSAID treatment with chemotherapy [Citation16,Citation47]. One study on advanced lung cancer patients was excluded from this review as the indication was not to treat cancer cachexia [Citation1]. This trial randomized between chemotherapy with or without the COX-2 inhibitor rofecoxib [Citation16]. The NSAID group had significantly better response rate, global QoL, physical function, fatigue and significantly less weight loss. In addition the response rate (41% vs. 26%), but not survival improved. As rofecoxib was removed from the market due to safety considerations, the NSAID arm was closed early. This study also demonstrated a trend towards increased severe cardiac ischemia in the rofecoxib arm (p= 0.06). In contrast, another trial with advanced lung cancer only showed a non-significant improvement in progression free survival in patients with low COX-2 expression and no effect on QoL with the combination of high dose celecoxib and chemotherapy [Citation47]. Weight was not assessed. No significant difference of cardiac events during or after chemotherapy (p =0.50) was reported.

Due to the conflicting evidence and relatively low rate of side effects it seems prudent not to discontinue NSAID use in cancer patients as a general rule, but only to do so when there is increased risk of side effects such as in patients with cardiovascular events (COX-2) or gastrointestinal bleeding.

Future studies

Despite the overall positive findings in the reviewed literature, there is a need for further trials on NSAIDs as several studies are small and uncontrolled. Due to many dropouts in studies including patients with short expected survival and the unlikelihood of clinical meaningful effects in patients with refractory cachexia, future trials should probably aim to include patients with early cachexia or cachexia syndrome.

It would be useful to study several animal models to guide the choice of NSAID in future cachexia trials and to better understand cachexia pathophysiology. The importance of COX-2 should be considered as COX-1 inhibitors may be less effective in treating cachexia [Citation48]. In one study indomethacin appeared to reduce weight loss and this was accompanied by a decrease in plasma prostaglandin E2 [Citation42]. Other studies have however shown almost equal effects of indomethacin and celecoxib [Citation48,Citation49] despite their different COX selectiveness. Such findings might suggest a non-prostaglandin effect is also of importance. The lack of an ideal rodent model for cachexia [Citation50] is roadblock that often leads to results that prove difficult to reproduce in human studies.

The current review does not provide a strong NSAID recommendation, as no obvious differences in effects and side effects are identified. The between-patient variations in effect and side effects are often greater than the variations between different NSAIDs [Citation51], and in addition on must assume some class effect on cachexia. So far, three NSAIDs have been studied in humans with cachexia; indomethacin, celecoxib and ibuprofen. Indomethacin is no longer is available in several countries and is sometimes considered unsuitable due to CNS side effects. Celecoxib could be argued to be the drug of choice due to mechanisms and best documentation. Most cachexia trials with celecoxib do nevertheless exclude patients with prior cardiac events, which might be prudent as there are interactions between history of atherosclerotic heart disease [Citation52] and the development of cardiovascular adverse events on COX-2 inhibitors. One published protocol does not have this contraindication, which could be advocated in view of a low frequency of side effects [Citation10]. On the other hand, among clinicians ibuprofen is often considered the safest NSAID, but it will have increased side effects at higher doses, including also cardiac events [Citation53]. Unfortunately, the use of ibuprofen may be limited due to considerations of risk of gastrointestinal bleeding in frail patients as will celecoxib (if all with cardiovascular disease are excluded). The choice of NSAID is accordingly still debatable.

Due to only limited success with unimodal strategies and the concept of matching the complex pathophysiology of cachexia to complex therapeutic strategies, several cachexia trials are now based on a multimodal approach. Examples of multimodal treatments include combinations of drugs or the addition of exercise training, nutrition and/or psychosocial counseling.

Further trials with NSAIDs for the treatment of cachexia are recommended as these drugs have low costs and seem promising with regard to efficacy and side effects; however, NSAIDs probably do not have the potential to be of great clinical significance as single agents. Future studies should include multimodal treatment, have a randomized design and have a sufficient sample size.

Conclusion

Based on the present systematic literature review there is evidence that NSAIDs can improve weight in cancer patients with cachexia. There is also some evidence that NSAIDs may improve performance status, self-reported QoL, and inflammation. Studies are generally small and a few are methodologically flawed, often due to multiple outcomes with excess risk of false positives. The evidence is still insufficient to recommend NSAIDs with the intention of treating cachexia outside clinical trials. This conclusion is further supported based on the known side effects of NSAIDs, even though the present literature reports almost negligible toxicity.

http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2012.724536

Download PDF (167.7 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank the trained research advisor Ingrid Riphagen for her assistance in the systematic search.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

David Blum: EURO IMPACT, European Intersectorial and Multidisciplinary Palliative Care Research Training, is funded by the European Union Seventh Framework Programme [FP7/2007–2013, under grant agreement n8 (264697)].

References

- Fearon KC. Cancer cachexia: Developing multimodal therapy for a multidimensional problem. Eur J Cancer 2008;44:1124–32.

- Fearon K, Strasser F, Anker SD, Bosaeus I, Bruera E, Fainsinger RL, . Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: An international consensus. Lancet Oncol 2011;12:489–95.

- Yavuzsen T, Davis MP, Walsh D, LeGrand S, Lagman R. Systematic review of the treatment of cancer-associated anorexia and weight loss. J Clin Oncol 2005;23: 8500–11.

- Murphy KT, Lynch GS. Update on emerging drugs for cancer cachexia. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs 2009;14: 619–32.

- Argiles JM, Moore-Carrasco R, Fuster G, Busquets S, Lopez-Soriano FJ. Cancer cachexia: The molecular mechanisms. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2003;35:405–9.

- Laviano A, Inui A, Meguid MM, Molfino A, Conte C, Rossi Fanelli F. NPY and brain monoamines in the pathogenesis of cancer anorexia. Nutrition 2008;24:802–5.

- Madeddu C, Dessi M, Panzone F, Serpe R, Antoni G, Cau MC, . Randomized phase III clinical trial of a combined treatment with carnitine +celecoxib ± megestrol acetate for patients with cancer-related anorexia/cachexia syndrome. Clin Nutr Epub 2011 Nov 4.

- Lundholm K, Korner U, Gunnebo L, Sixt-Ammilon P, Fouladiun M, Daneryd P, . Insulin treatment in cancer cachexia: Effects on survival, metabolism, and physical functioning. Clin Cancer Res 2007;13:2699–706.

- Daneryd P, Svanberg E, Korner U, Lindholm E, Sandstrom R, Brevinge H, . Protection of metabolic and exercise capacity in unselected weight-losing cancer patients following treatment with recombinant erythropoietin: A randomized prospective study. Cancer Res 1998;58: 5374–9.

- Rogers ES, MacLeod RD, Stewart J, Bird SP, Keogh JW. A randomised feasibility study of EPA and Cox-2 inhibitor (Celebrex) versus EPA, Cox-2 inhibitor (Celebrex), resistance training followed by ingestion of essential amino acids high in leucine in NSCLC cachectic patients – ACCeRT study. BMC Cancer 2011;11:493.

- Induru RR, Lagman RL. Managing cancer pain: Frequently asked questions. Cleveland Clin J Med 2011;78:449–64.

- Ghosh N, Chaki R, Mandal V, Mandal SC. COX-2 as a target for cancer chemotherapy. Pharmacol Report 2010;62:233–44.

- Rothwell PM, Price JF, Fowkes FG, Zanchetti A, Roncaglioni MC, Tognoni G, . Short-term effects of daily aspirin on cancer incidence, mortality, and non-vascular death: Analysis of the time course of risks and benefits in 51 randomised controlled trials. Lancet Epub 2012 Mar 24.

- Rothwell PM, Wilson M, Price JF, Belch JF, Meade TW, Mehta Z. Effect of daily aspirin on risk of cancer metastasis: A study of incident cancers during randomised controlled trials. Lancet Epub 2012 Mar 24.

- Higgins JPT GSe. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration. Available from: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org.2011.

- Gridelli C, Gallo C, Ceribelli A, Gebbia V, Gamucci T, Ciardiello F, . Factorial phase III randomised trial of rofecoxib and prolonged constant infusion of gemcitabine in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: The GEmcitabine-COxib in NSCLC (GECO) study. Lancet Oncol 2007;6: 500–12.

- Dawson SJ, Michael M, Biagi J, Foo KF, Jefford M, Ngan SY, . A phase I/II trial of celecoxib with chemotherapy and radiotherapy in the treatment of patients with locally advanced oesophageal cancer. Invest New Drugs 2007;2:123–9.

- Jackson NA, Barrueco J, Soufi-Mahjoubi R, Marshall J, Mitchell E, Zhang X, . Comparing safety and efficacy of first-line irinotecan/fluoropyrimidine combinations in elderly versus nonelderly patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: Findings from the bolus, infusional, or capecitabine with camptostar-celecoxib study. Cancer 2009;12:2617–29.

- Preston T, Fearon KC, McMillan DC, Winstanley FP, Slater C, Shenkin A, . Effect of ibuprofen on the acute-phase response and protein metabolism in patients with cancer and weight loss. Br J Surg 1995;2:229–34.

- Shinohara N, Kumagai A, Kanagawa K, Maruyama S, Abe T, Sazawa A, . Multicenter phase II trial of combination therapy with meloxicam, a COX-2 inhibitor, and natural interferon-alpha for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Jap J Clin Oncol 2009;11:720–6.

- Creagan ET, Buckner JC, Hahn RG, Richardson RR, Schaid DJ, Kovach JS. An evaluation of recombinant leukocyte A interferon with aspirin in patients with metastatic renal cell cancer. Cancer 1988;61:1787–91.

- Wigmore SJ, Falconer JS, Plester CE, Ross JA, Maingay JP, Carter DC, . Ibuprofen reduces energy expenditure and acute-phase protein production compared with placebo in pancreatic cancer patients. Br J Cancer 1995;1:185–8.

- Hyltander A, Korner U, Lundholm KG. Evaluation of mechanisms behind elevated energy expenditure in cancer patients with solid tumours. Eur J Clin Invest 1993;23:46–52.

- Mantovani G, Madeddu C, Maccio A, Gramignano G, Lusso MR, Massa E, . Cancer-related anorexia/cachexia syndrome and oxidative stress: An innovative approach beyond current treatment. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2004;13:1651–9.

- Lindholm E, Daneryd P, Körner U, Hyltander A, Fouladiun M, Lundholm K. Effects of recombinant erythropoietin in palliative treatment of unselected cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res 2004;20:6855–64.

- Daneryd P. Epoetin alfa for protection of metabolic and exercise capacity in cancer patients. Semin Oncol 2002; 29 (3 Suppl 8):69–74.

- Lundholm K, Gelin J, Hyltander A, Lonnroth C, Sandstrom R, Svaninger G, . Anti-inflammatory treatment may prolong survival in undernourished patients with metastatic solid tumors. Cancer Res 1994;54:5602–6.

- Lundholm K, Daneryd P, Bosaeus I, Körner U, Lindholm E. Palliative nutritional intervention in addition to cyclooxygenase and erythropoietin treatment for patients with malignant disease: Effects on survival, metabolism, and function. Cancer 2004;9:1967–77.

- Lundholm K, Daneryd P, Korner U, Hyltander A, Bosaeus I. Evidence that long-term COX-treatment improves energy homeostasis and body composition in cancer patients with progressive cachexia. Int J Oncol 2004;24:505–12.

- Lai V, George J, Richey L, Kim HJ, Cannon T, Shores C, . Results of a pilot study of the effects of celecoxib on cancer cachexia in patients with cancer of the head, neck, and gastrointestinal tract. Head Neck 2008;30: 67–74.

- Maccio A, Madeddu C, Gramignano G, Mulas C, Floris C, Sanna E, . A randomized phase III clinical trial of a combined treatment for cachexia in patients with gynecological cancers: Evaluating the impact on metabolic and inflammatory profiles and quality of life. Gynecol Oncol Epub 2011 Dec 27.

- Mantovani G, Maccio A, Madeddu C, Gramignano G, Lusso MR, Serpe R, . A phase II study with antioxidants, both in the diet and supplemented, pharmaconutritional support, progestagen, and anti-cyclooxygenase-2 showing efficacy and safety in patients with cancer-related anorexia/cachexia and oxidative stress. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2006;15:1030–4.

- Mantovani G, MacCio A, Madeddu C, Serpe R, Antoni G, Massa E, . Phase II nonrandomized study of the efficacy and safety of COX-2 inhibitor celecoxib on patients with cancer cachexia. J Mol Med 2010;88:85–92.

- Cerchietti LC, Navigante AH, Peluffo GD, Diament MJ, Stillitani I, Klein SA, . Effects of celecoxib, medroxyprogesterone, and dietary intervention on systemic syndromes in patients with advanced lung adenocarcinoma: A pilot study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2004;27:85–95.

- Cerchietti LC, Navigante AH, Castro MA. Effects of eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic n-3 fatty acids from fish oil and preferential Cox-2 inhibition on systemic syndromes in patients with advanced lung cancer. Nutr Cancer 2007;59:14–20.

- McMillan DC, O’Gorman P, Fearon KC, McArdle CS. A pilot study of megestrol acetate and ibuprofen in the treatment of cachexia in gastrointestinal cancer patients. Br J Cancer 1997;76:788–90.

- McMillan DC, Wigmore SJ, Fearon KC, O’Gorman P, Wright CE, McArdle CS. A prospective randomized study of megestrol acetate and ibuprofen in gastrointestinal cancer patients with weight loss. Br J Cancer 1999;79:495–500.

- Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, Zee B, Pater J. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol 1998;16:139–44.

- Jones LW, Hornsby WE, Goetzinger A, Forbes LM, Sherrard EL, Quist M, . Prognostic significance of functional capacity and exercise behavior in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2012;76:248–52.

- McGettigan P, Henry D. Cardiovascular risk with non–steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: Systematic review of population-based controlled observational studies. PLoS Med 2011;8:e1001098.

- Schlondorff D. Renal complications of nonsteroidal anti–inflammatory drugs. Kidney Int 1993;44: 643–53.

- Cahlin C, Korner A, Axelsson H, Wang W, Lundholm K, Svanberg E. Experimental cancer cachexia: The role of host-derived cytokines interleukin (IL)-6, IL-12, interferon-gamma, and tumor necrosis factor alpha evaluated in gene knockout, tumor-bearing mice on C57 Bl background and eicosanoid-dependent cachexia. Cancer Res 2000;60: 5488–93.

- Yao M, Zhou W, Sangha S, Albert A, Chang AJ, Liu TC, . Effects of nonselective cyclooxygenase inhibition with low-dose ibuprofen on tumor growth, angiogenesis, metastasis, and survival in a mouse model of colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2005;11:1618–28.

- Ninomiya I, Nagai N, Oyama K, Hayashi H, Tajima H, Kitagawa H, . Antitumor and anti-metastatic effects of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition by celecoxib on human colorectal carcinoma xenografts in nude mouse rectum. Oncol Report 2012;28:777–84.

- Baris D, Karagas MR, Koutros S, Colt JS, Johnson A, Schwenn M, . Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and other analgesic use and bladder cancer in northern New England. Int J Cancer Epub 2012 Apr 17.

- Brasky TM, Potter JD, Kristal AR, Patterson RE, Peters U, Asgari MM, . Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cancer incidence by sex in the VITamins And Lifestyle (VITAL) cohort. Cancer Cause Control 2012;23: 431–44.

- Groen HJ, Sietsma H, Vincent A, Hochstenbag MM, van Putten JW, van den Berg A, . Randomized, placebo-controlled phase III study of docetaxel plus carboplatin with celecoxib and cyclooxygenase-2 expression as a biomarker for patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: The NVALT-4 study. J Clin Oncol 2011;29: 4320–6.

- Davis TW, Zweifel BS, O’Neal JM, Heuvelman DM, Abegg AL, Hendrich TO, . Inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 by celecoxib reverses tumor-induced wasting. J Pharmacol Exp Therapeut 2004;308:929–34.

- Peluffo GD, Stillitani I, Rodriguez VA, Diament MJ, Klein SM. Reduction of tumor progression and paraneoplastic syndrome development in murine lung adenocarcinoma by nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Int J Cancer 2004;110:825–30.

- Fearon KC, Glass DJ, Guttridge DC. Cancer cachexia: Mediators, signaling, and metabolic pathways. Cell Metab Epub 2012 Jul 17.

- Grosser T. Variability in the response to cyclooxygenase inhibitors: Toward the individualization of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy. J Invest Med 2009;57: 709–16.

- Bertagnolli MM, Eagle CJ, Zauber AG, Redston M, Breazna A, Kim K, . Five-year efficacy and safety analysis of the Adenoma Prevention with Celecoxib Trial. Cancer Prev Res 2009;2:310–21.

- Trelle S, Reichenbach S, Wandel S, Hildebrand P, Tschannen B, Villiger PM, . Cardiovascular safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: Network meta–analysis. BMJ 2011;342:c7086.