Abstract

Few studies have evaluated initiatives targeting implementation of cancer rehabilitation. In this study we aim to test the effects of a complex intervention designed to improve general practitioners’ (GPs) involvement in cancer rehabilitation. Outcomes were proactive contacts to patients by their GP reported by the patients and GPs, respectively, and patients’ participation in rehabilitation activities. Methods. Cluster randomised controlled trial. All general practices in Denmark were randomised to an intervention group or to a control group (usual procedures). Patients were subsequently allocated to the intervention or the control group based on randomisation status of their GP. Between May 2008 and February 2009, adult patients treated for incident cancer at Vejle Hospital, Denmark, were assessed for eligibility. A total of 323 general practices were included, allocating 486 patients to an intervention and 469 to a control group. The intervention included a patient interview about rehabilitation with a rehabilitation coordinator at the hospital, comprehensive information to the GP about individual needs for rehabilitation, and an encouragement to the GP to contact the patient proactively. Questionnaires were administered to patients and GPs at 14 months after inclusion. Results. At baseline average age of patients was 63 years and 72% were female. The most frequent cancer localisations were breast (43%), lung (15%), and malignant melanoma (8%). The intervention had no effect on either patient- or GP-reported extent of GP proactivity. Further, no effect was observed on patient participation in rehabilitation activities during the 14-month follow-up period. Discussion. The intervention had no effect on GP proactivity or on patient participation in rehabilitation activities. However, analyses showed a significant association between proactivity and participation and we, therefore, conclude that increased GP proactivity may facilitate patient participation in rehabilitation activities.

Rehabilitation is defined by the World Health Organization as “a process intended to enable people with disabilities to reach and maintain optimal physical, sensory, intellectual, psychological and/or social function” [Citation1], which is the conceptual frame for this intervention. The theoretical basis of the intervention was based on the assumption that rehabilitation is a complex and long-lasting process of interactions between patients, their relatives and health professionals [Citation2–4]. In order to succeed, the rehabilitation process is dependent on adequate information to patients about rehabilitation and awareness of unmet supportive care needs by patients as well as health professionals [Citation5,Citation6], appropriate communication between health care sectors [Citation7–9], and availability of relevant rehabilitation activities. Finally, proactive action by the general practitioner (GP) is requested by patients [Citation10–13] and may also contribute positively to the rehabilitation course. The intervention was therefore designed to encourage GPs to be proactive regarding the patients’ cancer rehabilitation. GPs generally have some knowledge about the patients’ prior health status, mental vulnerability and social network, and may, therefore, be able to initiate and coordinate the rehabilitation process, identify the patients’ upcoming needs, and refer to relevant rehabilitation activities when needed [Citation14]. Currently, the role of GPs in rehabilitation is not organisationally well-defined [Citation13,Citation15]. However, studies show that GPs are willing to take on responsibility for the rehabilitation [Citation11], and that the patients wish their GPs were more proactive in doing so [Citation11–13]. So far, interventions aimed at reducing cancer patients’ unmet needs or improving their quality of life have shown only sporadic improvements [Citation16–20]. The complexity of the concept of rehabilitation, different opinions about the definition and measurement of unmet supportive care needs [Citation21] and how to use and interpret patient-reported outcomes (PROs), the diversity of the cancer trajectory and symptom burden [Citation22] and implications of cancer for each individual patient, as well as the context in which the intervention is carried out [Citation23], may all influence the patients’ quality of life and thereby contribute to the lack of intervention effect. Research is needed to uncover each aspect of the chain and process measures will therefore give valuable information. Hence, we designed a multimodal intervention aimed at influencing the different levels of the process of the rehabilitation course for each individual patient [Citation1,Citation2,Citation4].

Since the intervention itself was multifaceted, the possible effects were wide-ranging and could affect outcomes at different levels of the rehabilitation process. We therefore included validated questionnaires measuring health-related quality of life as the primary outcome (EORTC QLQ-C30) [Citation24], psychological distress (POMS) [Citation25] and patient satisfaction with their GP [DanPEP (Danish version of EuroPEP)] [Citation26] as secondary outcome measures, along with ad hoc questions evaluating participation in rehabilitation activities and proactive contacts to patients by their GP.

We have previously shown that the complex intervention giving the GP an enhanced role had no statistically significant effect on health-related quality of life (HRQOL) or on psychological distress following cancer [Citation19]. The objective of this paper was to evaluate effects of the intervention on GP proactivity, on patients’ participation in rehabilitation activities, and finally on whether proactivity is associated with patients’ participation in rehabilitation.

Material and methods

We conducted a cluster randomised, controlled trial where all general practices in Denmark were randomised to an intervention group or to a control group by means of the unique provider number of each practice. Patients were subsequently allocated according to the randomisation of their GP. Feasibility of the intervention and the study details have previously been published [Citation27].

Participants

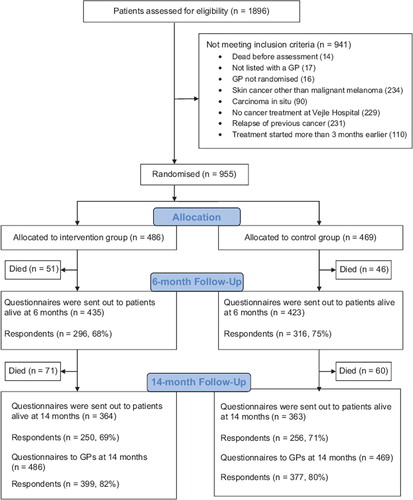

All adult patients (≥ 18 years) newly diagnosed with cancer and admitted to Vejle Hospital between 12 May 2008 and 28 February 2009 were assessed for eligibility. Patients were included if treated at Vejle Hospital for a cancer diagnosed within the previous three months and if listed with a general practice. Patients with carcinoma in situ or non-melanoma skin cancers were not included ().

Two rehabilitation coordinators (RCs), both nurses with oncological experience, assessed all patients for eligibility and managed the intervention. The patients were sampled across departments, cancer type, cancer stage, and potential rehabilitation needs by use of the electronic patient files [Citation27].

Setting

The study was conducted at Vejle Hospital, a public general hospital in the Region of Southern Denmark (1.2 million inhabitants). Cancer patients were allocated from all of Denmark.

The Danish publicly funded healthcare system ensures free access to general practice, and GPs function as gatekeepers to the rest of the healthcare system. More than 98% of all Danish residents are registered with a general practice. On average each GP meets nine incident cancer patients during one year [Citation28].

GPs’ opportunities to refer patients to relevant rehabilitation activities vary between the different municipalities, just as the availability of private patient associations and other relief organisations. These conditions might influence the quality of the rehabilitation offered.

Development and piloting of questionnaires and intervention

Before designing the intervention we reviewed papers, reports and textbooks about the problems faced by cancer patients and GPs with respect to individual rehabilitation and continuity across healthcare sectors [Citation2–4,Citation10,Citation20].

The questionnaires and the procedures of identification, assessment, and inclusion of patients were pilot tested prior to study start. The procedures have been described in detail elsewhere [Citation27].

The intervention

The intervention comprised a patient interview about rehabilitation needs conducted by the two RCs, followed by information to the GP about the patient's individual rehabilitation needs and cancer patients’ rehabilitation needs in general. The core of the information was that the GP was encouraged to proactively contact the patient to facilitate a rehabilitation process ().

Patient interviews were conducted according to an interview guide [Citation29] and based on a list of general needs and problems among cancer patients (). The list was produced based on existing literature on cancer patients’ needs and problems during the cancer trajectory [Citation2,Citation4]. Interviews were most often conducted at the hospital, but in some cases by phone. During the interview, the concept of rehabilitation was explained and the individual needs for physical, psychological, sexual, social, work- and finance-related rehabilitation were identified. It was explained that physical, psychological, sexual, social, work-related and financial problems might occur at any time and change during the disease trajectory [Citation6,Citation30]. In order to address these problems, patients were advised to consult their GP during treatment and after discharge. The patients gave oral consent firstly to their GP being informed about their individual problems and needs and secondly to their GP being encouraged to be proactive regarding the rehabilitation.

Following each interview, the patient's GP was informed about the patient's actual problems and needs for rehabilitation and encouraged to be proactive, i.e. the GP was encouraged to contact the patient personally to offer support and guidance in order to identify and address actual and future needs for rehabilitation. Subsequently, the GP received an e-mail summarising the information, supplemented by general information about cancer patients’ needs and problems (). The information was personally conveyed by phone, if possible, and always sent electronically along with the more general information. Patients and GPs in the control group received the usual care and were not contacted by the RCs [Citation27].

Outcomes and sampling of data

Questionnaires were administered to patients in both groups after 6 and 14 months of follow-up, and to GPs of patients of both groups after 14 months of follow-up as described in detail in [Citation27]. The 14-month questionnaires comprised items specifically designed for measuring effects on GPs’ proactivity and on patients’ participation in rehabilitation activities.

GP data evaluating proactive contacts to patients were assessed by one ad hoc question asking the GP “Have you at any time from the patient's diagnosis and until now contacted the patient yourself to encourage him/her to make an appointment for a talk about the course of the disease and the different consequences of the cancer disease?” (“Several times”, “Once”, “Never”).

Patient data evaluating GP proactive contact to patients were assessed by one ad hoc question asking to which degree the patient would agree (“Fully agree”, “Agree”, “Disagree”, “Fully disagree”, “Don't know”, “Not relevant”) in the following statement “I experienced that my general practitioner offered his/her support by himself/herself”. Patient data evaluating participation in rehabilitation activities were assessed by one ad hoc question asking, “Have you from diagnosis and until now participated in any of the following activities due to problems caused by your cancer disease?” (Listing of possible providers/activities).

Data were sampled in identical ways irrespective of allocation status by use of patient questionnaires administered to patients alive at 14 months after inclusion. Non-responders were sent one reminder after three weeks [Citation27].

Sample size

The sample size was estimated based on the primary outcome measure, HRQOL, measured by The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30 questionnaire [Citation24] as described in detail in [Citation19].

Randomisation

Prior to study start, all 2181 general practices in Denmark were randomly allocated to the intervention (n = 1091) or control (n = 1090) group by the unique provider number of each practice using a computerised random-number generator in the statistical program Stata version 10.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Hence, randomisation was performed at practice level, meaning that all GPs working under the same provider number were allocated to the same group. Consequently, spill-over effect between GPs and patients from the same practice was minimised.

Blinding

The study was not blinded. The list of randomisation was available to the RCs during assessment of patient eligibility. Allocation status was obvious during the intervention.

Statistical analysis

Baseline patient characteristics were described using descriptive statistics presenting the distribution of age, sex and cancer type. Proactive contact to patients reported by patients was dichotomised to “Proactive contact” (combining “Agree” and “Fully agree”) and “No proactive contact” (combining “Disagree” and “Fully disagree”). “Don't know” and “Not relevant” were treated as missing. Proactive contact to patients reported by GPs was dichotomised to “Proactive contact” (combining “Several times” and “Once”) and “No proactive contact” (“Never”).

Patient participation in rehabilitation activities was described by defining three categories of activities based on profession of the provider/activity: 1) “Physical activities” (physiotherapist, occupational therapist, chiropractor, patient education, smoking cessation counselling, nutritional information, physical training, and alternative practitioner including acupuncturist and reflexologist); 2) “Psychological activities” (psychologist, marriage counsellor or sexologist, supportive group sessions or patient associations, and spiritual counselling); and 3) “work-related/financial activities” (social worker, union representative or employer, financial or insurance counsellor). Furthermore, the variable “Participation in one or more activities” was defined based on all of the above-mentioned activities [Citation31].

We conducted analyses using mixed model logistic regression with random effects accounting for possible cluster effects caused by the cluster randomisation. All outcomes were adjusted for confounding effect of age and sex. All tests were two-sided, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Adjusted odds ratios (ORadj) are presented with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Missing values were regarded as missing at random. We conducted complete case analyses.

The statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 11.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Ethics

The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (J.nr. 2008-41-1887). The Regional Committee on Biomedical Research Ethics evaluated the project and concluded that the intervention did not need an approval from the Danish National Committee on Biomedical Research Ethics according to Danish law (Project-ID: S-20082000-7).

Trial registration at ClinicalTrials.gov, registration ID number NCT01021371.

Results

In total 506 (53%) of the 955 included patients completed the 14-month follow-up questionnaire. However, since 228 (24%) patients had died during the follow-up period, the response rate was 70% overall [506/(955-228)] (). Patients were on average 62.5 years and 80% were female. The most frequent cancer locations were breast (55.7%), colorectal (15.0%), and malignant melanoma (12.0%). The distribution of gender and cancer type with an overweight of women with breast cancer compared to cancer patients in general reflects Vejle Hospitals’ specialisation in this group of patients. Patients in intervention and control groups showed similar baseline characteristics (). The response rates among GPs after 14 months of follow-up were 82% (399/486) and 80% (377/469) for intervention and control group GPs, respectively (). After 14 months of follow-up, the total number of patients responding was 506. However, not all of the patients answered all questions, which is reflected in the number of answers of the different items reported in , and . Similarly, of the 776 GPs who send in the questionnaire, 752 answered the item on proactivity.

Table I. Baseline patient characteristics of the respondents after 14 months of follow-up.

Table II. Proactive contact to patients by general practitioner during 14-month follow-up, patient-reported (n = 324).

Table III. Proactive contact to patients by general practitioner during 14-month follow-up, GP-reported (n = 752).

Table IV. Patient participation in rehabilitation activities during 14-month follow-up after diagnosis (n = 483).

Table V. Effect of proactive contact to patients by the general practitioner (reported by patients) on patient participation in rehabilitation activities during the 14-month follow-up period (n = 318).

The intervention had no effect on either patient-reported () or GP-reported () extent of GP proactivity. We did, however, observe similar levels of patient- and GP-reported proactivity since 56% of the patients and 58% of the GPs reported proactive behaviour by the GP. Among the intervention group patients and GPs, the degree of proactivity was 60% and 61%, respectively ( and ). Agreement between patient- and GP-reported proactivity was 62.7%. Further, no effect of the intervention was observed on patient participation in rehabilitation activities during the 14-month follow-up period ().

We conducted an analysis of the association between GP proactive contact to the patients and participation in rehabilitation activities (). This analysis showed statistically significantly more patients participating in one or more rehabilitation activities among the group of patients reporting to have been contacted proactively by their GP during the follow-up period. A similar tendency was observed for each of the three subgroups of activities (physical, psychological and work-related/ financial), but the effects were not statistically significant.

Discussion

Principal findings

This comprehensive intervention showed no effect on GP proactivity, either patient-reported or GP-reported, or on patient participation in rehabilitation activities. However, analyses showed that statistically significantly more patients participated in one or more rehabilitation activities among the group of patients reporting to have been contacted proactively by their GP during the follow-up period.

Strengths and limitations

Since the sample size was assessed based on the primary outcome, HRQOL, there might have been insufficient power to detect any statistically significant differences between the groups with respect to the secondary outcomes. However, since all confidence intervals were reasonably narrow we would have detected relevant effects. There were no validated instruments measuring participation in rehabilitation activities or proactivity among GPs. Therefore, we constructed ad hoc questions. The pilot test showed that these questions have sufficient variability and we are therefore confident that they are appropriate for measuring the relevant effects.

We found an agreement of patient- and GP- reported proactivity of only 62.7%. Discrepancies in understanding of what it said and done may leave patient and GP with some very different impressions about what actually happened. Similarly, patients and GPs may understand the term “contacted by himself/herself” differently. Also, recall bias might have caused some of the differences in reporting proactivity. The high degree of proactivity in both groups, GP-reported as well as patient-reported, may indicate that proactive behaviour is common among Danish GPs ( and ). However, 40% of the GPs were not proactive, leaving substantial room for improvement.

The level of participation in rehabilitation activities might have been influenced by patient-experienced symptoms or problems not caused by the cancer or the cancer treatment. However, this influence was expected to be similar in the two groups.

The cluster randomisation was performed to ensure that GPs only had patients in either the intervention or the control group. We have no reason to believe that information about the study was disseminated between GPs in the two groups. Hence, spill-over effects were of no or only minor magnitude.

We included patients with various cancer types, different prognosis, health problems and needs of supportive care. The inhomogeneity of the study population might have diluted effects in groups of patients with specific problems or diagnoses. It cannot be ruled out that a similar intervention might have effect on subgroups of patients with specific cancers or special needs.

Relations to other studies

Proactive behaviour by the GP is repeatedly requested by cancer patients [Citation10–13], but most often not sufficiently supplied [Citation4,Citation11]. In this study we found a rather high percentage of proactivity among GPs in the intervention group as well as in the control group, and the levels of patient- and GP-reported proactivity were similar ( and ). However, we found no significant effect on proactivity by the intervention, even though GPs in the intervention group were specifically encouraged to contact the patients. To our knowledge, no other studies have tested the impact of an intervention on the extent of GP proactivity in cancer rehabilitation. Based on our observation that proactivity is associated with a higher degree of participation in rehabilitation activities, future research should focus on how to mobilise the GPs to be proactive. The lesson from our study is that, even though the majority of GPs are proactive towards cancer patients, it is very difficult to promote further proactivity among GPs. This may be a phenomenon not restricted to cancer care [Citation32].

Participation in activities is a decisive step of rehabilitation. To our knowledge, no other studies have tested the effect of an intervention on participation in cancer rehabilitation activities. Patient participation in rehabilitation activities has been described in three studies [Citation31,Citation33,Citation34], one describing utilisation of professional supportive care services for breast cancer women [Citation34], the remaining two describing participation on rehabilitation activities [Citation31] and psychosocial support [Citation33] in a mixed site cancer population. The three studies described participation rates in rehabilitation activities ranging from 28% [Citation33] to 52% [Citation31]. Our study showed participation rates as high as 56% (intervention group) and 55% (control group) for participation in one or more activities ().

Meaning

The intervention had no statistically significant effect on GP proactivity or on patients’ participation in different rehabilitation activities. Some GPs in the intervention group may have increased their own contribution to rehabilitation in the consultations. The reduced use (statistically insignificant) of external psychological rehabilitation in the intervention group () may indicate that some psychological interventions may have been carried out in general practice. As there was statistically significant association between proactivity and participation we conclude that increased GP proactivity may facilitate patient participation in rehabilitation activities. This association might partly be explained by an existing close relationship between the proactive GP and some of the patients, leading the GP to be proactive. At the same time, due to special characteristics of these patients they may be more likely to participate in rehabilitation activities. The finding of this association indicates that proactivity seems to be an important factor for a successful rehabilitation course. However, implementing proactive behaviour among GPs is difficult. Perhaps even more attention should be on how to promote proactive behaviour in general practice. Cultural and behavioural changes may take a long time to obtain and structural reorganisation is probably needed, including political and economic incentives supporting proactivity continuously. Along with factors within general practice itself, communication between primary and secondary sectors, including the handing over of the patient from hospital to GP after treatment, still needs attention despite numerous initiatives aiming to optimise these central elements of cancer care and rehabilitation. Future research should focus on how to promote proactive behaviour among GPs. Also, the content and quality of the proactive contacts should be carefully evaluated in order to optimise every step of the rehabilitation course. Many interventions aiming to improve cancer patients’ rehabilitation and especially the psychosocial aspects have shown little or no effect on patient outcomes [Citation16–18,Citation20,Citation21]. Therefore, there is a great challenge ahead for future research in designing new interventions that will actually improve patients’ quality of life and satisfaction. These challenges should, however, not keep us from trying to find new effective ways of helping cancer patients and we still believe that general practice should play an important role in doing so.

In conclusion, this comprehensive intervention had no effect on GP proactivity, neither patient- nor GP-reported, or on patient participation in rehabilitation activities.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all patients and healthcare professionals who took part in the study. We also wish to thank Lise Keller Stark, Research Unit of General Practice, University of Southern Denmark, for proofreading the manuscript and Susanne Døssing Berntsen for managing datasets.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

This study was funded by the Danish Cancer Society, the Novo Nordisk Foundation and the Region of Southern Denmark. The National Research Center for Cancer Rehabilitation is funded by the Danish Cancer Society. The authors’ work was independent from the funders. All authors have received no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

References

- World Health Organisation (Internet) [cited 2012 Aug ]. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/rehabilitation/en.

- Mikkelsen TH, Sondergaard J, Jensen AB, Olesen F. Cancer rehabilitation: Psychosocial rehabilitation needs after discharge from hospital? Scand J Prim Health Care 2008;26:216–21.

- Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in transition. Washington, D.C.: Comittee on Cancer Survivorship. Improving Care and Quality of Life, National Cancer Policy Board, Institute of Medicine, and National Research Council 2006.

- Groenvold M, Pedersen C, Jensen CR, Faber MT, Johnsen AT. The cancer patient’s world–an investigation of the problems experienced by Danish cancer patients. Copenhagen: Danish Cancer Society. 2006.

- Steele R, Fitch MI. Supportive care needs of women with gynecologic cancer. Cancer Nurs 2008;31:284–91.

- Armes J, Crowe M, Colbourne L, Morgan H, Murrells T, Oakley C, . Patients’ supportive care needs beyond the end of cancer treatment: A prospective, longitudinal survey. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:6172–9.

- Jones R, Regan M, Ristevski E, Breen S. Patients’ perception of communication with clinicians during screening and discussion of cancer supportive care needs. Patient Educ Couns 2011;85:e209–15.

- Smith SM, Allwright S, O’Dowd T. Does sharing care across the primary-specialty interface improve outcomes in chronic disease? A systematic review. Am J Manag Care 2008;14:213–24.

- Grunfeld E, Earle CC. The interface between primary and oncology specialty care: Treatment through survivorship. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2010;2010:25–30.

- Kendall M, Boyd K, Campbell C, Cormie P, Fife S, Thomas K, . How do people with cancer wish to be cared for in primary care? Serial discussion groups of patients and carers. Fam Pract 2006;23:644–50.

- Mikkelsen T, Sondergaard J, Sokolowski I, Jensen A, Olesen F. Cancer survivors’ rehabilitation needs in a primary health care context. Fam Pract 2009;26:221–30.

- Hall S, Gray N, Browne S, Ziebland S, Campbell NC. A qualitative exploration of the role of primary care in supporting colorectal cancer patients. Support Care Cancer Epub 2012 Mar 9.

- Lundstrom LH, Johnsen AT, Ross L, Petersen MA, Groenvold M. Cross-sectorial cooperation and upportive care in general practice: Cancer patients’ experiences. Fam Pract 2011;28:532–40.

- Olesen F, Dickinson J, Hjortdahl P. General practice – time for a new definition. BMJ 2000;320:354–7.

- Dalsted RJ, Guassora AD, Thorsen T. Danish general practitioners only play a minor role in the coordination of cancer treatment. Dan Med Bull 2011;58:A4222.

- Johansson B, Brandberg Y, Hellbom M, Persson C, Petersson LM, Berglund G, . Health-related quality of life and distress in cancer patients: Results from a large randomised study. Br J Cancer 2008;99:1975–83.

- Rottmann N, Dalton SO, Bidstrup PE, Wurtzen H, Hoybye MT, Ross L, . No improvement in distress and quality of life following psychosocial cancer rehabilitation. A randomised trial. Psychooncology 2012;21:505–14.

- Fors EA, Bertheussen GF, Thune I, Juvet LK, Elvsaas IK, Oldervoll L, . Psychosocial interventions as part of breast cancer rehabilitation programs? Results from a systematic review. Psychooncology 2011;20:909–18.

- Bergholdt SH, Larsen PV, Kragstrup J, Sondergaard J, Hansen DG. Enhanced involvement of general practitioners in cancer rehabilitation: A randomised controlled trial. BMJ open 2012;2:e000764. Epub 2012 Apr 18.

- Holtedahl K, Norum J, Anvik T, Richardsen E. Do cancer patients benefit from short-term contact with a general practitioner following cancer treatment? A randomised, controlled study. Support Care Cancer 2005;13:949–56.

- Carey M, Lambert S, Smits R, Paul C, Sanson-Fisher R, Clinton-McHarg T. The unfulfilled promise: A systematic review of interventions to reduce the unmet supportive care needs of cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2012;20:207–19.

- Kjaer TK, Johansen C, Ibfelt E, Christensen J, Rottmann N, Høybye MT, . Impact of symptom burden on health related quality of life of cancer survivors in a Danish cancer rehabilitation program: A longitudinal study. Acta Oncol 2011;50:223–32.

- Hansen HP, Tjørnhøj-Thomsen T, Johansen C. Rehabilitation interventions for cancer survivors: The influence of context. Acta Oncol 2011;50:259–64.

- Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, . The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993;85:365–76.

- Baker F, Denniston M, Zabora J, Polland A, Dudley WN. A POMS short form for cancer patients: Psychometric and structural evaluation. Psychooncology 2002;11:273–81.

- Vedsted P, Sokolowski I, Heje HN. Data quality and confirmatory factor analysis of the Danish EUROPEP questionnaire on patient evaluation of general practice. Scand J Prim Health Care 2008;26:174–80.

- Hansen DG, Bergholdt SH, Holm L, Kragstrup J, Bladt T, Sondergaard J. A complex intervention to enhance the involvement of general practitioners in cancer rehabilitation. Protocol for a randomised controlled trial and feasibility study of a multimodal intervention. Acta Oncol 2011;50:299–306.

- Pedersen KM, Andersen JS, Sondergaard J. General practice and primary health care in Denmark. J Am Board Fam Med 2012;25:S34–8.

- Kurtz SM, Silverman JD. The Calgary-Cambridge Referenced Observation Guides: An aid to defining the curriculum and organizing the teaching in communication training programmes. Med Educ 1996;30:83–9.

- McDowell ME, Occhipinti S, Ferguson M, Dunn J, Chambers SK. Predictors of change in unmet supportive care needs in cancer. Psychooncology 2010;19:508–16.

- Holm LV, Hansen DG, Johansen C, Vedsted P, Larsen PV, Kragstrup J, . Participation in cancer rehabilitation and unmet needs: A population-based cohort study. Support Care Cancer 2012;20:2913–24.

- Smelt AF, Blom JW, Dekker F, van den Akker ME, Knuistingh Neven A, Zitman FG, . A proactive approach to migraine in primary care: A pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Can Med Assoc J 2012;184:E224–31.

- Plass A, Koch U. Participation of oncological outpatients in psychosocial support. Psychooncology 2001;10:511–20.

- Gray RE, Goel V, Fitch MI, Franssen E, Chart P, Greenberg M, . Utilization of professional supportive care services by women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2000;64:253–8.