Abstract

The external validity of trial results is a matter of debate, and no strong evidence is available to support whether a trial may have a positive or a negative effect on the outcome of patients. Methods. We compared the results of stage IV colorectal cancer patients treated within a large Dutch phase III trial (CAIRO), in which standard chemotherapy and standard safety eligibility criteria were used, to patients treated outside the trial during the trial accrual period in a representative selection of 29 Dutch hospitals. Non-trial patients were identified by the Netherlands Cancer Registry (NCR), and were checked for the trial eligibility criteria. Results. The NCR registered 1946 stage IV colorectal cancer patients who received chemotherapy, of whom 394 patients were included in the CAIRO trial and 30 patients in other trials. Thus, the CAIRO trial participation rate was 20%. In the 29 hospitals, 162 patients received chemotherapy in the trial and 396 patients received chemotherapy outside the trial. Of the non-trial patients, 224 patients fulfilled the trial eligibility criteria. The overall survival of eligible non-trial patients was comparable to trial patients (HR 1.03, p = 0.70). However, non-eligible non-trial patients had a significantly worse outcome (HR 1.70, p < 0.01). Conclusion. These data provide evidence in a common tumor type that trial results have external validity, provided that standard eligibility criteria are being observed. Our finding of a worse outcome for patients not fulfilling these criteria strongly argues against the use of cancer treatments in other patient categories than included in the original trials in which these treatments were investigated.

Clinical trials are an essential tool for the evaluation of novel medical drugs and technologies, and the results of these trials provide the strongest backbone of evidence-based medicine. Clinicians often assume that trial participation is beneficial for the individual patient, mainly because of the increased attention given to trial patients as compared to patients treated in daily practice. However, earlier reviews [Citation1–4] have not provided strong evidence that trial participation improves outcome, although a trend towards a positive effect was noted. These reviews identified differences in interventions as well as patient characteristics in- and outside trials as possible confounders. In a more recent systematic review, which was not restricted to cancer trials, no evidence was found for either a beneficial or a harmful effect of trial participation [Citation5].

We have conducted a national multicenter investigator-initiated prospective randomized phase III trial in advanced colorectal cancer patients on the sequential versus the combined use of standard cytotoxic drugs: capecitabine, oxaliplatin and irinotecan [Citation6,Citation7]. The study medication of this trial concerned standard drugs and regimens, which therefore provided the opportunity to compare the outcome of trial patients with patients who were treated with chemotherapy outside the trial during the trial accrual period. This analysis also allowed the trial participation rate to be assessed. Here we present the results of this analysis.

Material and methods

Patients participating in the trial

Between January 2003 and December 2004, 820 advanced colorectal cancer patients were included in the investigator-initiated phase III randomized CAIRO trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00312000) of the Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group (DCCG) [Citation6,Citation7]. Of these, 396 patients presented with stage IV disease (i.e. synchronous metastases), of whom two patients were later found ineligible and were therefore excluded from the survival analysis. CAIRO is the only trial to date in which the sequential versus the combined use of all three cytotoxic drugs with efficacy in colorectal cancer has been prospectively investigated. Patients were randomized between first-line capecitabine, second-line irinotecan, and third-line capecitabine + oxaliplatin (sequential treatment arm) and first line capecitabine + irinotecan and second-line capecitabine + oxaliplatin (combination treatment arm). All cytotoxic drugs were administered at their recommended doses and schedules, and treatment was required to start within one week of randomization. The main eligibility criteria included histologically proven colorectal cancer in an advanced stage not amenable to curative surgery, measurable or assessable disease parameters, and no previous systemic treatment for advanced disease. Previous adjuvant chemotherapy was allowed provided that the last administration was given at least six months before randomization. Eligible patients were required to have a WHO performance score of 0–2 and adequate hepatic, bone marrow and renal functions. Exclusion criteria included serious concomitant disease preventing the safe administration of chemotherapy or likely to interfere with the study assessments; other malignancies in the past five years with the exception of adequately treated carcinoma in situ of the cervix and squamous or basal cell carcinoma of the skin; pregnancy or lactation; patients with reproductive potential not implementing adequate contraceptive measures; central nervous system metastases; serious active infections; inflammatory bowel disease or other diseases associated with chronic diarrhea; previous extensive irradiation of the pelvis or abdomen; concomitant administration of any other experimental drug; concurrent treatment with any other anti-cancer therapy. A total of 79 of the approximately 100 Dutch hospitals participated in this study.

Patients not participating in the trial

Non-trial patients were identified by using data from the Netherlands Cancer Registry (NCR), which registers all cancer patients at primary diagnosis. This implies that metastatic patients are only registered when they present with synchronous metastases, i.e. stage IV. Therefore, non-trial patients with metachronous metastases could not be included in the analysis. All stage IV colorectal cancer patients who were diagnosed during the CAIRO trial accrual period and who received chemotherapy were identified in the NCR.

Comparison of trial with non-trial patients

For reasons mentioned above, the comparison was restricted to stage IV patients. To compare the outcome between trial and non-trial patients, non-trial patients were identified. For a more detailed analysis, 29 hospitals were selected which were considered to be representative for Dutch healthcare (three university hospitals, 14 large teaching hospitals, and 12 general hospitals). This was further checked by comparing the median overall survival of all stage IV patients in these 29 hospitals with all other patients identified by the NCR. Of these 29 hospitals, 26 hospitals participated in the CAIRO trial. The medical files of all stage IV colorectal cancer patients who received chemotherapy outside the CAIRO trial in these 29 hospitals were reviewed. Data were collected on baseline characteristics, CAIRO eligibility criteria, treatment schedule, and survival. These data were compared with data from stage IV patients included in the CAIRO trial. Trial participation was assessed by comparing the number of patients included in the CAIRO trial with the total number of patients who did not participate but would have been eligible for the CAIRO trial.

Statistics

Baseline patient characteristics of trial versus non-trial patients were compared using the Students t-test for continuous variables and χ2-test for dichotomous or nominal values. Overall survival was calculated in all patients from the date of diagnosis until death or censored on the date last known to be alive. This was done to allow a fair comparison of trial versus non-trial patients. Of note, the overall survival in the CAIRO trial was originally calculated from the date of randomization.

The median overall survival was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and trial patients were compared to non-trial patients by means of the log-rank test. Multivariate analysis was performed with the Cox-Proportional Hazards Model. The analyses were performed with SPSS statistical software (version 18). All statistical tests were two-tailed, using a 5% significance level.

Results

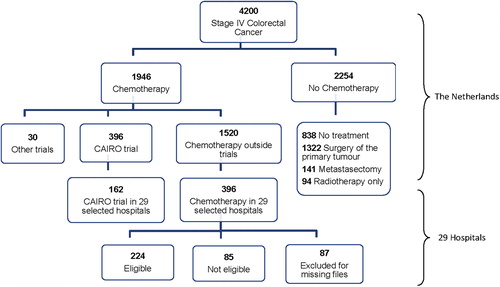

During the accrual period of the CAIRO trial, 4200 patients were registered by the NCR with stage IV colorectal adenocarcinoma, of whom 1946 patients received palliative chemotherapy (). Of these, 396 patients were included in the CAIRO trial, 30 patients in other ongoing trials, and 1520 patients received chemotherapy outside the scope of trials. Of the 2254 patients who did not receive chemotherapy, 838 patients did not receive any treatment, 1322 patients had a resection of the primary tumor of whom 141 patients also had a metastasectomy, and 94 patients were treated with radiotherapy.

Figure 1. Flow chart of the 4200 patients who were diagnosed with stage IV colorectal cancer during the CAIRO trial accrual period.

In the 29 selected hospitals, the NCR identified 558 stage IV CRC patients who received chemotherapy, of whom 162 patients were included in the CAIRO trial and 396 patients received chemotherapy outside the trial. The median overall survival in these 396 patients from these 29 hospitals did not significantly differ from the total of 1120 patients with stage IV disease who have received chemotherapy as identified by the NCR (data not shown), supporting the representability of the 29 hospitals. After review of the medical files of these 396 patients, 224 patients were identified who fulfilled all eligibility criteria for the CAIRO trial and therefore could have been included in this trial. Of the remaining 172 patients, 85 patients did not meet the trial eligibility criteria and 87 patients were not included in this analysis because of missing files. In 91 of the 224 eligible non-trial patients, the actual baseline performance status was not scored in the files, but was considered to be within the limits of the CAIRO inclusion criteria based on descriptive data in the patient files.

Reasons for non-participation of the 224 eligible non-trial patients were patient refusal (47 patients), treatment in non-participating hospital (50), logistical reasons (13), possible metastasectomy considered (eight) and unknown (106). Reasons for non-eligibility in 85 patients were (more than one reason possible per patient): poor performance status (44), serious comorbidity (16), laboratory abnormalities (12), second malignancy in the past five years (10), no evaluable disease parameter (seven), CNS metastases (three), and other reasons (12).

Outcome of trial versus non-trial patients

Baseline characteristics of the 224 non-trial patients who fulfilled all eligibility criteria of the CAIRO trial were comparable to the 394 eligible trial patients (). The 85 ineligible non-trial patients had a significantly worse performance status, more often an increased alkaline phosphatase and less often had a resection of their primary tumor.

Table I. Patient characteristics.

First-line treatment of the 224 eligible non-trial patients consisted of fluoropyrimidine monotherapy in 130 patients (58%) and combination chemotherapy in 94 patients (42%). By randomization this was 50%–50% in the CAIRO trial. Eligible non-trial patients receiving first-line monotherapy were significantly older compared with patients receiving first-line combination therapy, with a mean age of 64 versus 58 years, respectively (p < 0.0001). There was no difference in the number of cycles in first line treatment between the eligible non-trial patients [7.2 (95% CI 6.2–8.2)] and trial patients [7.8 (95% CI 7.2–8.4)]. None of the patients received bevacizumab or epidermal growth factor receptor antibodies in first-line treatment since these drugs were not yet available during the study period.

The median overall survival of eligible stage IV non-trial patients and stage IV trial patients was 15.7 months and 17.0 months from the date of diagnosis, respectively (p = 0.7, HR 1.03, 95% CI 0.87–1.23) (). Median overall survival of ineligible non-trial patients was 9.3 months, which was significantly worse when compared to trial patients (p < 0.01, HR 1.70, 95% CI 1.33–2.17). Median overall survival of patients not receiving any chemotherapy (n = 2254) was 4.5 months (95% CI 4.1–4.9). The median age in this patient group was significantly higher (72 years, range 29–96). In a Cox proportional Hazards model with WHO performance status, number of metastatic sites, resection of the primary tumor, location of the primary tumor, serum LDH, and serum alkaline phosphatase, we did not observe a significant difference in overall survival between eligible non-trial and trial patients (HR 1.1, 95% CI 0.98–1.25).

Trial participation

With 1946 non-trial stage IV colorectal cancer patients treated with chemotherapy identified during the trial accrual period and 394 stage IV patients actually included in the trial, the trial participation to the CAIRO trial was 20%. In addition, 30 patients were treated during the same period in trials other than CAIRO. Thus, overall trial participation during this period for stage IV cancer patients was 22%. When all diagnosed stage IV patients were considered the overall trial participation was 10%.

Discussion

We have compared the outcome in terms of overall survival between advanced colorectal cancer patients treated within the scope of a clinical trial and patients treated outside this trial during the same period. A large Dutch multicenter phase III randomized trial (CAIRO) in advanced colorectal cancer was used as the reference trial, which was performed within the framework of a cooperative group (DCCG) in approximately 80% of Dutch hospitals. In this trial the standard cytotoxic drugs for advanced colorectal cancer were used at their normal doses and schedules, and standard entry criteria were used that are also applicable to the safe use of these drugs in daily practice. Moreover both arms of the trial were used in daily practice already. This use of standard treatments in both arms provided the opportunity to compare the outcome of trial patients with non-trial patients who were treated during the trial accrual period.

We observed no difference in median overall survival between trial and non-trial patients when non-trial patients were selected by trial eligibility criteria, but we found a significantly reduced overall survival in non-trial patients who did not meet these eligibility criteria. Several comments should be made on this result.

Our analysis is restricted to patients with stage IV (i.e. synchronous) metastases, since the NCR only registers patients at primary diagnosis. Previously published data from the CAIRO study have shown a comparable survival for patients with synchronous as compared to patients with metachronous metastases, when only synchronous metastatic patients were considered in whom a resection of the primary tumor was performed [Citation8]. In a subsequent study we provided arguments that the worse prognosis that is generally reported for synchronous metastatic patients may be attributed to the fact that in many of these patients a resection of the primary tumor is not performed [Citation9]. This may explain the shorter median overall survival of the patients in this study as compared to the median survival in more unselected patients with both synchronous and metachronous metastases treated with chemotherapy. Since a significantly smaller percentage of non-eligible non-trial patients had their primary tumor resected, this could have contributed to their worse outcome (). However, since the absolute difference was relatively small, we do not consider this factor to be the only reason for the worse outcome of these patients. The worse PS of the non-eligible non-trial patients may also have been a relevant factor. In any case, the prognostic value of resection of the primary tumor has not been firmly established and is currently the subject of ongoing prospective phase III studies such as the CAIRO4 trial.

Due to the straightforward design and the use of standard drugs for this indication, the conduct of the trial was easily feasible in all Dutch hospitals, and patient referral to specialized centers was therefore not required. Incentives such as access to experimental drugs with promising activity or high investigator fees were not applicable in this trial. Reasons for non-participation were retrospectively checked in the selected patient population, but it appeared that these data were not recorded in the files of the majority of patients.

Several factors have been described that could influence whether a trial in comparison with daily care may have a positive or a negative effect on the outcome of patients [Citation3]. A possible trial effect was hypothesized to be attributed to five possible factors: the therapy, the protocol, the care, the Hawthorne effect and a placebo effect. The authors of this systematic review concluded that, although the evidence was not conclusive and the available data were limited, it is more likely that participation in a clinical trial had a positive effect. The effect appeared largest in trials in which an already established and effective treatment was applied. However, given the fact that standard drugs and schedules were administered in both treatment arms of the CAIRO trial we do not believe that such an effect is present in our analysis. Neither can differences in care or placebo effect be considered as important factors to improve the outcome of this trial in comparison with daily practice. Other factors such as patient age, geographical and social barriers on clinical trial accrual have been described [Citation10,Citation11], but we did not investigate these factors in our study.

The external validity of trial results has previously been a matter of concern [Citation12]. However, the external validity of this trial is further supported by the fact that eligible patients in the trial and outside the trial together represented almost 70% of the stage IV patients receiving chemotherapy as identified by the NCR during the trial accrual period.

The CAIRO trial eligibility criteria involved no restrictions other than related to the safe use of standard chemotherapeutic drugs. Our finding of a significantly reduced overall survival in non-trial stage IV colorectal cancer patients who did not meet the trial eligibility criteria is a strong argument for the strict use of these criteria in general practice. Studies on the outcome of treatments in general practice, which are often initiated by healthcare authorities on (usually expensive) drugs, should therefore always evaluate whether patients did meet the standard eligibility criteria for these drugs. The worse outcome of non-trial versus trial patients that have been reported by others [Citation13] is most likely due to the fact that many non-trial patients did not meet the trial eligibility criteria.

The large group of patients who did not receive any chemotherapy had a poor median survival of 4.5 months. This group was significantly older compared to the trial patients. Older patients are frequently underrepresented in cancer clinical trials [Citation11]. However, many colorectal cancer trials have shown that age by itself does not indicate a worse outcome of systemic treatment [Citation14]. The main outcome of our study is that trial results can only be expected in the general population if the same selection criteria are applied.

Lastly, the CAIRO trial had a high participation rate of 20%. We consider it unlikely that trial participation rates differ between patients with synchronous and metachronous metastatic colorectal cancer. Our trial participation rate exceeds the commonly reported 5–14% in cancer trials [Citation15], although these latter findings were not always restricted to patients actually receiving treatment as in our analysis. In a more selected population study a participation rate of 30% [Citation13] has been reported, which shows the possibility of a high participation rate in hospitals in which a protocol is available for the majority of patients. The simple and straightforward design of the CAIRO trial, its use of standard drugs and the clinically relevant study objective will likely have had a positive effect on trial participation.

In conclusion, for stage IV colorectal cancer patients we did not demonstrate a difference in outcome between patients included in a clinical trial and patients treated during the same period outside that trial but who met the trial eligibility criteria. Patients treated outside the trial not meeting the eligibility criteria had a significantly worse outcome. These results strongly indicate that the external validity of trial results only applies when trial eligibility criteria are respected in general practice. This also implies that for patient groups not fulfilling the safety criteria of trials in which the efficacy of a certain drug regimen was demonstrated, the treatment results should be monitored and compared to the patient groups with the same characteristics not receiving the study drug (preferably in a randomized trial) in order to assess the risks and benefits of the drug regimen in these selected groups. Such policy may in the end reduce the costs of healthcare.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group, the Comprehensive Cancer Centre Netherlands, Nijmegen, The Netherlands, and an unrestricted scientific grant from Sanofi-Aventis. The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Stiller CA. Centralised treatment, entry to trials and survival. Br J Cancer 1994;70:352–62.

- Peppercorn JM, Weeks JC, Cook EF, Joffe S. Comparison of outcomes in cancer patients treated within and outside clinical trials: Conceptual framework and structured review. Lancet 2004;363:263–70.

- Braunholtz DA, Edwards SJ, Lilford RJ. Are randomized clinical trials good for us (in the short term)? Evidence for a “trial effect”.J Clin Epidemiol 2001;54:217–24.

- ECRI. Patients’ reasons for participation in clinical trials and effect of trial participation on patient outcomes. [cited 2010 Jun 26] Available from: https://www.ecri.org/Documents/Clinical_Trials_Patient_Guide_Evidence_Report.pdf;2002.

- Vist GE, Hagen KB, Devereaux PJ, Bryant D, Kristoffersen DT, Oxman AD. Outcomes of patients who participate in randomised controlled trials compared to similar patients receiving similar interventions who do not participate. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007:MR000009.

- Koopman M, Antonini NF, Douma J, Wals J, Honkoop AH, Erdkamp FL, et al. Sequential versus combination chemotherapy with capecitabine, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin in advanced colorectal cancer (CAIRO): A phase III randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2007;370:135–42.

- Koopman M, Antonini NF, Douma J, Wals J, Honkoop AH, Erdkamp FL, et al. Randomised study of sequential versus combination chemotherapy with capecitabine, irinotecan and oxaliplatin in advanced colorectal cancer, an interim safety analysis. A Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group (DCCG) phase III study. Ann Oncol 2006;17:1523–8.

- Mekenkamp LJ, Koopman M, Teerenstra S, van Krieken JH, Mol L, Nagtegaal ID, et al. Clinicopathological features and outcome in advanced colorectal cancer patients with synchronous vs. metachronous metastases. Br J Cancer 2010;103:159–64.

- Venderbosch S, de Wilt JH, Teerenstra S, Loosveld OJ, van Bochove A, Sinnige HA, et al. Prognostic value of resection of primary tumor in patients with stage IV colorectal cancer: Retrospective analysis of two randomized studies and a review of the literature. Ann Surg Oncol 2011; 18:3252–60.

- Sateren WB, Trimble EL, Abrams J, Brawley O, Breen N, Ford L, et al. How sociodemographics, presence of oncology specialists, and hospital cancer programs affect accrual to cancer treatment trials. JCO 2002;20:2109–17.

- Townsley CA, Selby R, Siu LL. Systematic review of barriers to the recruitment of older patients with cancer onto clinical trials. JCO 2005;23:3112–24.

- Rothwell PM. External validity of randomised controlled trials: “To whom do the results of this trial apply?”. Lancet 2005;365:82–93.

- Sorbye H, Pfeiffer P, Cavalli-Bjorkman N, Qvortrup C, Holsen, MH, Wentzel-Larsen T, et al. Clinical trial enrollment, patient characteristics, and survival differences in prospectively registered metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Cancer 2009;115:4679–87.

- Power DG, Lichtman SM. Chemotherapy for the elderly patient with colorectal cancer. Cancer J 2010;16:241–52.

- Lara PN, Jr., Higdon R, Lim N, Kwan K, Tanaka M, Lau DH, et al. Prospective evaluation of cancer clinical trial accrual patterns: Identifying potential barriers to enrollment. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:1728–33.