Abstract

Objective. Little is known about the development of psychological wellbeing over time among women who have been treated for breast cancer. The aim of this study was to identify distinct patterns of distress, anxiety, and depression in such women.

Methods. We invited 426 consecutive women with newly diagnosed primary breast cancer to participate in this study, and 323 (76%) provided information on distress (‘distress thermometer’) and on symptoms of anxiety and depression (‘hospital anxiety and depression scale’). Semiparametric group-based mixture modeling was used to identify distinct trajectories of distress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms assessed the week before surgery and four and eight months later. Logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate the characteristics of women in the distinct groups.

Results. Although no sub-group of women with chronic severe anxiety or depressive symptoms was found, we did identify a sub-group of 8% of the women who experienced continuously severe distress. Young age, having a partner, shorter education, and receiving chemotherapy but not radiotherapy might characterize women whose psychological symptoms remain strong eight months after diagnosis.

Conclusion. By looking beyond the mean, we found that 8% of the women experienced chronic severe distress; no sub-groups with chronic severe anxiety or depression were identified. Several socio-demographic and treatment factors characterized the women whose distress level remained severe eight months after diagnosis. The results suggest that support could be focused on relatively small groups of patients most in need.

Poor psychological wellbeing in cancer patients has, despite its impact on daily functioning, often been overlooked [Citation1,Citation2] and frequently untreated [Citation3], possibly affecting treatment compliance and cancer survival [Citation4]. More attention is now being paid to the psychological burden of cancer survivors and to targeting psychological support to those most in need. The national guidelines in the US require systematic screening for psychological distress [Citation5], which could be performed with instruments such as the distress thermometer [Citation6]. Previous studies have shown that the mean severity of distress declines within the first year among women with breast cancer [Citation7] and that the severity of depression and anxiety symptoms among cancer survivors overall declines to population levels within two years of diagnosis [Citation8]. Little is known, however, about adjustment of distress over time, as only one previous study has examined distress development measured with the distress thermometer [Citation7].

Distress is a broad construct, covering a wide continuum of emotions related to symptoms of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder [Citation9]. The prevalence of distress symptoms in cancer patients is often reported to be above 30% [Citation10], that of depressive symptoms to be 10–25% [Citation11], and that of anxiety to be 10–30% [Citation12]. A high prevalence of comorbid symptoms of anxiety and depression has been reported, and genetic risk factors for both are strongly correlated [Citation13]. Anxiety and depressive symptoms can also occur independently and progress quite differently after a breast cancer diagnosis. Several studies have examined whether participants were above or below a certain cut-off score for psychological outcomes over time, possibly exaggerating small differences among them [Citation14]. Examination of the full range of scores shows that only two previous studies determined overall distress trajectories [Citation15,Citation16], and only four identified distinct trajectories of anxiety and depression symptoms separately or together [Citation17–20]. Although the results were mixed, several factors, including age, education, social support, and treatment characteristics, have been suggested to affect distress, anxiety, and depression after a cancer diagnosis [Citation15–22]. The study reported here is the first to look beyond the mean and to investigate distinct patterns of distress, anxiety, and depression in women with incident breast cancer prospectively from before primary surgery and at four and eight months after operation. Furthermore, we examined the characteristics (including age, education, social support, wish for psychological support, and treatment characteristics) of women with the most adverse psychological trajectories.

Methods

Participants

The data used were collected for a previously described questionnaire-based study and have resulted in two papers on distress measured at baseline [Citation21,Citation23]. Between 1 October 2008 and 1 October 2009, consecutive patients with newly diagnosed (< 4 weeks after diagnosis) primary breast cancer who were to undergo surgery (< 1 week before operation) at the Breast Surgery Clinic of Copenhagen University Hospital, Rigshospitalet, Denmark, were evaluated for eligibility (age ≥ 18 years, Danish-speaking, living in Denmark, no severe cognitive impairment). Of the 426 women who were invited, 357 (84%) filled out a questionnaire before the operation (baseline) and four and/or eight months later.

Measurements

Distress, anxiety, and depression were assessed at baseline and four and/or eight months later. Distress was measured with the distress thermometer, which consists of a single item, with responses ranging from 0 to 10 [Citation6], which we validated in a Danish context where a cut-off score of ≥ 7 was found appropriate in terms of sensitivity and specificity for identifying breast cancer patients with high psychological distress [Citation23]. The hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) is a 14-item self-reported scale to measure the severity of symptoms of depression and anxiety (referred to in this paper as depression and anxiety) in non-psychiatric patients [Citation24], with responses reported on a four-point Likert scale and total scores of 0–21. The commonly used cut-off scores of 0–7, 8–10, and 11–21 indicate non-cases, doubtful cases, and cases, respectively. The reliability and validity of the scale has been established, also in cancer patients [Citation25]. Anxiety and depression were entered as continuous variables.

Responses to the baseline questionnaire on the following factors were included to characterize the population: age (included continuously as five-year intervals), education (< 13 years or unknown, ≥ 13 years), having a partner (“yes” or “no”), and having someone outside the family to rely on (“yes” or “no”). Desire for referral for psychological support was measured from answers to the item “Would you like to be referred for professional psychological support or treatment? Note that your answer will not result in actual referral”, with the response categories “yes”, “maybe, but not at the moment”, and “no”. Data on chemotherapy, endocrine treatment, and radiotherapy (all “yes” or “no”) were derived from the Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group, which holds detailed information on nearly 95% of all breast cancer cases in Denmark since 1977 [Citation26].

Statistical analyses

In order to identify sub-groups of women with breast cancer with distinct patterns of distress, anxiety, and depression, we used the TRAJ finite mixture model procedure, which allows modeling of censored normal distribution variables [Citation27]. First, logit transformation was applied, as many observations were close to the boundaries of all three psychological scales. We then tested TRAJ models with one to five trajectory groups; the final number of trajectories was selected on the basis of the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and Akaike information criterion (AIC). The higher the BIC or AIC, the better the model fits. When determining the number of groups, models were assumed to be of second order (both linear and quadratic terms were included), and the minimal group size was at least 5% of participants. After determining the number of groups, we assessed the shape of the trajectories by comparing the BIC and AIC of two models for each psychological scale: one with a linear term and one with both a linear and a quadratic term. Two plots were drawn of the results of the TRAJ analyses of distress, anxiety, and depression. The first descriptive plot shows the mean values at each time for the groups in the TRAJ models, while the second plot shows the regression lines derived from the parameter estimates of the TRAJ models (see Supplemenary Figures 1–3, to be found online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2014.1002571). As we used logit transformation, the calculated values of the psychological scales were backward transformed. Sensitivity analyses were conducted of the models selected for women who had provided complete responses to measures of distress, anxiety, or depression at all three times.

Multinomal logistic regression analyses (proc logistic) were used to determine odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for mutually adjusted associations between characteristics and belonging to the group with the highest distress, anxiety, or depression, with posterior group membership probabilities used as weights [Citation28]. The normal distributions of distress, anxiety, and depression were tested and found to be appropriate. p-Values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The SAS statistical software package release 9.3 was used for the statistical analyses.

Results

Complete responses for the distress thermometer and the HADS were obtained from 323 (76%) women with breast cancer at baseline (< 1 week before primary surgery) and after four and eight months. The mean age of the women was 61 years (range, 28–88 years), most had medium or higher education (61%), had a partner (67%), reported support outside the family (87%), and reported that they might want referral for psychological support later (56%) ().

Table I. Demographic and clinical characteristics of 323 women with newly diagnosed breast cancer.

Model selection

The BIC, AIC, and estimated group probabilities of the tested models are shown in . For distress, the BIC and AIC levels supported a five-group model ( and Supplemenary Figures 1, to be found online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2014.1002571). For anxiety, the optimal model had four groups, but as one group covered only 4% of the population, the model was exchanged for a two-group model covering more than 5% ( and Supplemenary Figures 2, to be found online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2014.1002571). For depression, a five-group model was supported, but, as one group covered only 3%, this model was exchanged for a three-group model covering more than 5% ( and Supplemenary Figures 3, to be found online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2014.1002571). For all outcomes, second-order models were found to be the most appropriate. The number of responses to the measures of distress, anxiety, and depression varied over time: n = 312, n = 290 and n = 276 for distress; n = 306, n = 286 and n = 276 for anxiety; and n = 311, n = 291 and n = 275 for depression at baseline and at four and eight months, respectively. Sensitivity analyses of complete responses at all times (distress, n = 271; anxiety, n = 253; depression, n = 262) indicated similar results with the models selected; however, a model containing four groups was selected for depression.

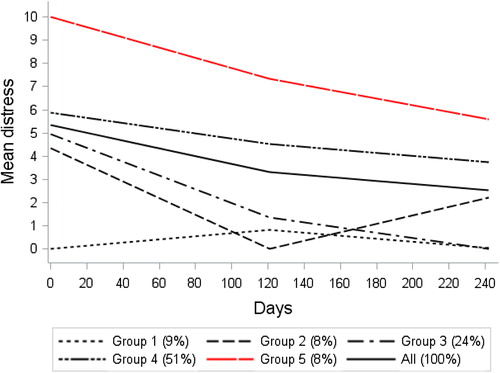

Figure 1. Mean severity of distress at breast cancer diagnosis and 4 and 8 months later according to the five groups identified in the TRAJ models for all women (n = 323).

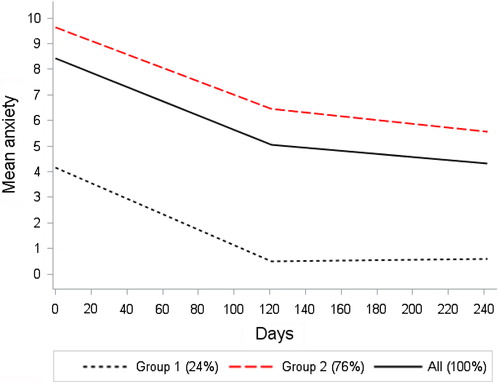

Figure 2. Mean severity of anxiety at breast cancer diagnosis and 4 and 8 months later according to the five groups identified in the TRAJ models for all women (n = 323).

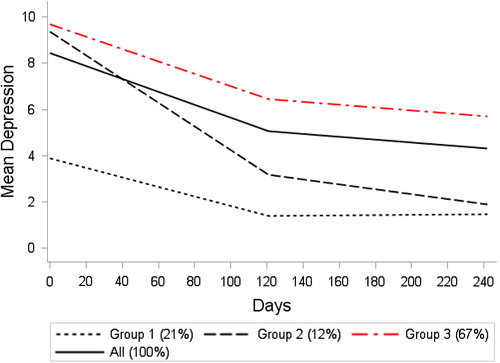

Figure 3. Mean severity of depression at breast cancer diagnosis and 4 and 8 months later according to the five groups identified in the TRAJ models for all women (n = 323).

Table II. Model selection results for distress, anxiety, and depression for 323 women with newly diagnosed breast cancer.

Description of distress, anxiety, and depression trajectories

As illustrated in and Supplemenary Figures 1, to be found online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2014.1002571, a sub-group of 8% of the women maintained severe distress throughout the eight months. and Supplemenary Figures 2, to be found online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2014.1002571 shows that women in group 2 (76%) moved from severe anxiety at diagnosis to a moderate level below the cut-off after four and eight months. and Supplemenary Figures 3, to be found online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2014.1002571 shows that women in group 3 (67%) had continuously moderately severe depressive symptoms.

Factors associated with distress, anxiety, and depression trajectories

Younger women, women without a partner, women with shorter education, women who did receive chemotherapy, and women who did not receive radiotherapy were more likely to experience the most severe distress (). For example, older women (measured in five-year intervals) had a 58% increased OR (OR = 1.58, CI 1.04–2.41) for having less distress (group 2) than severe distress (group 5). Women who received chemotherapy were more likely to experience the most severe distress and depression. Women who wished to be referred for psychological support were more likely to have severe anxiety. For several factors, including chemotherapy, the confidence intervals were wide.

Table III. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for mutually adjusted associations between characteristics and trajectories of high distress (reference group 5), anxiety symptoms (reference group 2), and depressive symptoms (reference group 3), respectively (N = 323).

Discussion

In this first study of distress trajectories measured with the distress thermometer, we identified five distinct trajectories for distress, two for anxiety and three for depression. The sub-groups with the most severe symptoms of both anxiety and depressive were below the cut-off score of 8 on the HADS; however, a sub-group of 8% of women continuously experienced severe distress (above score 7 on the distress thermometer) throughout the eight months of follow-up. Younger age, not having a partner, shorter education, and having received chemotherapy but not radiotherapy were associated with chronically severe distress.

Bonanno [Citation29] suggested four trajectories for adjustment to a traumatic life event: chronic, with continuously poor psychological functioning; recovery, with improving psychological functioning; delayed, with healthy followed by poor psychological functioning; and resilience, with a stable level of healthy psychological functioning. Direct comparison of our results with those of previous studies is difficult because of inconsistencies in the inclusion criteria (some studies included populations with cancers at various sites [Citation2,Citation19]), psychological measures [Citation15,Citation16,Citation18–20], follow-up period (during treatment [Citation18], during and after treatment [Citation15,Citation16,Citation19,Citation20]), and statistical analyses (some applying growth mixture modeling [Citation17–20]).

Distress

Two previous studies examined the trajectories of distress by comparing the full range of scores with dichotomized scores [Citation15,Citation16]. The first study, of 287 women with breast cancer, found improvement over time in mental health functioning measured with the SF-36 up to four years after diagnosis [Citation16], with a sub-group of 12% of the women who experienced poorer mental health. The second study, of 171 women, identified four trajectories of distress measured with the general health questionnaire in the first year after breast cancer [Citation15]. A sub-group of 15% of the women experienced chronically severe distress up to six months after the end of treatment. Thus, our results support those of previous studies, that a sub-group of women may experience chronic distress.

Anxiety

A previous study with growth mixture modeling examined trajectories of anxiety during four months after radiotherapy with the Spielberger state anxiety inventory (STAI-S) among 167 oncology outpatients with cancer of the breast, prostate, lung, or brain and their family caregivers [Citation19]. They found a sub-group of 30% of patients who experienced chronic severe anxiety. A study of trajectories of anxiety 1.5, 3, 6, and 12 months after diagnosis measured with the HADS in 192 women with breast cancer also applied growth mixture modeling [Citation17]. The authors identified four sub-groups, in one of which 9% of women experienced chronic anxiety. This finding is in contrast to ours.

Depression

In a previous study with growth mixture modeling, trajectories of depression measured on the Center for Epidemiological Studies depression scales (CES-D) were examined during the first six months after surgery among 398 women with breast cancer [Citation18]. Over 60% of the women belonged to one of three sub-groups with clinically significant levels of depressive symptoms. Another study with the CES-D and growth mixture modeling also identified three sub-groups among women with breast cancer [Citation20]. Lam [Citation17], using HADS-measured depression and growth mixture modeling, identified four sub-groups of which one comprising 9% experienced chronic depression. We did not identify a sub-group with severe depression.

Overall, the plots based on regression-derived, unadjusted parameter estimates (Supplemenary Figures 1–3, to be found online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2014.1002571) indicate that on each scale the symptoms decreased with time, which could be interpreted as some degree of recovery. We expected overlap among the trajectories of distress, anxiety, and depression in our study, as depression and anxiety have been shown often to occur concomitantly in the general population [Citation2,Citation30]. The absence of an overlap between the patterns for distress, anxiety, and depression could suggest that distress measured on the distress thermometer includes psychological aspects that lie beyond anxiety and depression as measured by HADS. Interestingly, the small group with continuously severe distress (8%) included women who had scored highest at baseline, before primary surgery. This may suggest that the most vulnerable women are already vulnerable before primary surgery and possibly even before that.

Factors associated with distinct trajectories of distress, anxiety, and depression

Previous studies with trajectory models have had mixed results with regard to the role of socio-demographic and treatment-related factors as predictors of psychological trajectories [Citation15–20]. In line with some [Citation18,Citation19] but not all studies [Citation15–17], we found that younger women might be at higher risk for chronic distress, perhaps because they often have (or plan to have) small children and may question their future ability to support their family in the face of a life-threatening disease. In agreement with one study [Citation20] but in contrast to three others [Citation17–19], we found that women without a partner are at higher risk for chronic distress. In agreement with two [Citation15,Citation17] and in contrast to one other study [Citation18], we observed that women with shorter education were at increased risk for chronic distress [Citation15], perhaps because they had fewer resources to face their situation. In contrast to three studies, we found an indication that receiving chemotherapy is associated with both severe distress and severe depression [Citation15–17], possibly indicating the effect of a heavy burden of physical symptoms. Contrary to our expectations, we found that women who received radiotherapy were at lower risk for chronic distress; this may be a chance finding and should be studied further. We found that a wish for referral for psychological support, a virtually unexplored issue [Citation17], was associated with higher anxiety symptoms. Thus, the socio-demographic and treatment-related risk factors of women with severe psychological symptoms remain incompletely characterized; they should be explored further to identify sub-groups in need for support.

This study is the first to examine trajectories of distress measured on the distress thermometer and to include psychological assessments from before surgery to four and eight months after. Further advantages include a consecutive sample, whereby all eligible women attending a breast cancer surgery clinic were invited, high-quality information on clinical and treatment characteristics from a national clinical database, and use of reliable, validated scales to measure anxiety, depression, and distress. Although the distress thermometer is not a good proxy for clinical depression and has no anchor points, it is considered a convenient, acceptable method for quantifying distress [Citation31]. Willingness to participate was seen in the current study (86%), but information was missing on selected items for 8% of the women, for unknown reasons. The total response rate of 76% was comparable to or higher than those of previous studies (e.g. 43% in [Citation2]). One limitation of our study is the wide confidence intervals, e.g. with regard to chemotherapy status, which indicate that a larger study population could have provided more reliable estimates.

Our sensitivity analyses of the models used for women for whom complete responses were available at all times revealed differences in the results for depression when a four-group model was selected. This suggests differences between women with complete responses with regard to depression (n = 262) and those with incomplete responses (n = 311), and selection bias cannot be excluded. We chose to retain our analyses, as exclusion of women for whom data were incomplete could also imply selection bias; nevertheless, our results should be generalized with caution. Finally, we followed up women only until eight months after diagnosis, as in the protocol for most women with breast cancer in Denmark adjuvant therapy finishes 6–7 months after diagnosis. A previous study suggested that the severity of distress may change even 2–6 months after the end of treatment, indicating that even longer follow-up would be preferable.

Conclusion

By looking beyond the mean to identify the breast cancer survivors most in need of support, we identified a sub-group of 8% of the women with breast cancer who continuously experienced severe distress, from primary surgery and throughout the first eight months after diagnosis. This group of women would not have been identified if we had used only population means. Younger age, not having a partner, shorter education, and having received chemotherapy but not radiotherapy may characterize women whose psychological symptoms remain severe eight months after diagnosis. It is reassuring that we found no sub-group of women with chronically severe anxiety or depression and that the sub-group of women with chronically severe distress represented only 8%. This suggests good recovery from psychological symptoms over time perhaps due to existing support. Also, our results suggest that support could be focused on a relatively small group of patients if screening-based psychological interventions prove to be effective [Citation32]. Future research should explore symptom trajectories, which are easily applicable, and not only population means.

Supplementary material available online

Supplementary Figure 1–3 to be found online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2014.1002571.

ionc_a_1002571_sm6713.pdf

Download PDF (509.2 KB)Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Nordic Cancer Union and the Committee for Psychosocial Cancer Research at the Danish Cancer Society. All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Fallowfield L, Ratcliffe D, Jenkins V, Saul J. Psychiatric morbidity and its recognition by doctors in patients with cancer. Br J Cancer 2001;84:1011–5.

- Boyes AW, Girgis A, D’Este CA, Zucca AC, Lecathelinais C, Carey ML. Prevalence and predictors of the short-term trajectory of anxiety and depression in the first year after a cancer diagnosis: A population-based longitudinal study. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:2724–9.

- von Heymann-Horan AB, Dalton SO, Dziekanska A, Christensen J, Andersen I, Mertz BG, et al. Unmet needs of women with breast cancer during and after primary treatment: A prospective study in Denmark. Acta Oncol 2013;52:382–90.

- Mols F, Husson O, Roukema JA, van de Poll-Franse LV. Depressive symptoms are a risk factor for all-cause mortality: Results from a prospective population-based study among 3,080 cancer survivors from the PROFILES registry. J Cancer Surviv 2013;7:484–92.

- Commission on Cancer of the American College of Surgeons. Cancer Program Standards 2012 Version 1.2: Ensuring patient-centered care. 2013. Chicargo, Illinois, American College of Surgeons.

- Roth AJ, Kornblith AB, Batel-Copel L, Peabody E, Scher HI, Holland JC. Rapid screening for psychologic distress in men with prostate carcinoma: A pilot study. Cancer 1998; 82:1904–8.

- Carlson LE, Waller A, Groff SL, Giese-Davis J, Bultz BD. What goes up does not always come down: Patterns of distress, physical and psychosocial morbidity in people with cancer over a one year period. Psychooncology 2013;22: 168–76.

- Mitchell AJ, Ferguson DW, Gill J, Paul J, Symonds P. Depression and anxiety in long-term cancer survivors compared with spouses and healthy controls: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:721–32.

- Carlson LE, Clifford SK, Groff SL, Maciejewski O, Bultz B. Screening for depression in cancer care. In: Mitchell AJ, Coyne JC, eds. Screening for Depression in Clinical Practice. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010:265–98.

- Jacobsen PB. Screening for psychological distress in cancer patients: Challenges and opportunities. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:4526–7.

- Pirl WF. Evidence report on the occurrence, assessment, and treatment of depression in cancer patients. Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2004;(32):32–9.

- Stark DP, House A. Anxiety in cancer patients. Br J Cancer 2000;83:1261–7.

- Kendler KS, Gardner CO, Gatz M, Pedersen NL. The sources of co-morbidity between major depression and generalized anxiety disorder in a Swedish national twin sample. Psychol Med 2007;37:453–62.

- Millar K, Purushotham AD, McLatchie E, George WD, Murray GD. A 1-year prospective study of individual variation in distress, and illness perceptions, after treatment for breast cancer. J Psychosom Res 2005;58:335–42.

- Henselmans I, Helgeson VS, Seltman H, de Vries J, Sanderman R, Ranchor AV. Identification and prediction of distress trajectories in the first year after a breast cancer diagnosis. Health Psychol 2010;29:160–8.

- Helgeson VS, Snyder P, Seltman H. Psychological and physical adjustment to breast cancer over 4 years: Identifying distinct trajectories of change. Health Psychol 2004;23: 3–15.

- Lam WW, Soong I, Yau TK, Wong KY, Tsang J, Yeo W, et al. The evolution of psychological distress trajectories in women diagnosed with advanced breast cancer: A longitudinal study. Psychooncology 2013;22:2831–9.

- Dunn LB, Cooper BA, Neuhaus J, West C, Paul S, Aouizerat B, et al. Identification of distinct depressive symptom trajectories in women following surgery for breast cancer. Health Psychol 2011;30:683–92.

- Dunn LB, Aouizerat BE, Cooper BA, Dodd M, Lee K, West C, et al. Trajectories of anxiety in oncology patients and family caregivers during and after radiation therapy. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2012;16:1–9.

- Donovan KA, Gonzalez BD, Small BJ, Andrykowski MA, Jacobsen PB. Depressive symptom trajectories during and after adjuvant treatment for breast cancer. Ann Behav Med 2014;47:292–302.

- Mertz BG, Bistrup PE, Johansen C, Dalton SO, Deltour I, Kehlet H, et al. Psychological distress among women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2012; 16:439–43.

- Christensen S, Zachariae R, Jensen AB, Vaeth M, Moller S, Ravnsbaek J, et al. Prevalence and risk of depressive symptoms 3–4 months post-surgery in a nationwide cohort study of Danish women treated for early stage breast-cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2009;113:339–55.

- Bidstrup PE, Mertz BG, Dalton SO, Deltour I, Kroman N, Kehlet H, et al. Accuracy of the Danish version of the ‘distress thermometer’. Psychooncology 2012;21:436–43.

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–70.

- Moorey S, Greer S, Watson M, Gorman C, Rowden L, Tunmore R, et al. The factor structure and factor stability of the hospital anxiety and depression scale in patients with cancer. Br J Psychiatry 1991;158:255–9.

- Moller S, Jensen MB, Ejlertsen B, Bjerre KD, Larsen M, Hansen HB, et al. The clinical database and the treatment guidelines of the Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group (DBCG]; its 30-years experience and future promise. Acta Oncol 2008;47:506–24.

- Jones BL, Nagin DS, Roeder K. A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating developmental trajectories. Sociolog Method Res 2001;29:374–93.

- Nagin DS. Analysing developmental trajectories: A semiparametric, group-based approach. Psychol Method 1999; 4:139–57.

- Bonanno GA. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? Am Psychol 2004;59:20–8.

- Merikangas KR, Zhang H, Avenevoli S, Acharyya S, Neuenschwander M, Angst J. Longitudinal trajectories of depression and anxiety in a prospective community study: The Zurich Cohort Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60: 993–1000.

- Mitchell AJ. Pooled results from 38 analyses of the accuracy of distress thermometer and other ultra-short methods of detecting cancer-related mood disorders. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:4670–81.

- Bidstrup PE, Johansen C, Mitchell AJ. Screening for cancer-related distress: Summary of evidence from tools to programmes. Acta Oncol 2011;50:194–204.