ABSTRACT

Background. The level of arterial ligation has been a variable of the Swedish Colorectal Cancer Registry since 2007. The aim of this study is to evaluate the accuracy of this registry variable in relation to anterior resection for rectal cancer.

Methods. The operative charts of all cardiovascularly compromised patients who underwent anterior resection during the period 2007–2010 in Sweden were retrieved and compared to the registry. We selected the study population to reflect the common assumption that these patients would be more sensitive to a compromised visceral blood flow. Levels of vascular ligation were defined, both oncologically and functionally, and their sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values, level of agreement and Cohen's kappa were calculated.

Results. Some 744 (94.5%) patients were eligible for analysis. Functional high tie level showed a sensitivity of 80.2% and a specificity of 90.1%. Positive and negative predictive values were 87.7 and 83.8%, respectively. Level of agreement was 85.5% and Cohen's kappa 0.70. The corresponding calculations for oncologic tie level yielded similar results.

Conclusion. The suboptimal validity of the Swedish Colorectal Cancer Registry regarding the level of vascular ligation might be problematic. For analyses with rare positive outcomes, such bowel ischaemia, or with minor expected differences in outcomes, it would be beneficial to collect data directly from the operative charts of the medical records in order to increase the chance of identifying clinically relevant differences.

When feasible, anterior resection for rectal cancer offers the potential for cure while alleviating the need for a permanent stoma. In an effort to decrease systemic recurrence and to possibly increase long-term survival, the concept of high arterial ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) flush to the aorta has been advocated [Citation1]. Benefits include resection of apical lymph nodes, which may be important for establishing and possibly improving the prognosis [Citation2]. Counterarguments abound, including the risk of decreased perfusion to the aboral colonic segment used for the anastomosis, thus increasing the risk for anastomotic leakage. This would be alleviated by instead ligating the superior rectal artery (SRA), distal to the left colic artery (LCA), thereby preserving the supply to the descending and sigmoid colon, while avoiding additional morbidity [Citation3]. As possible effects of the high arterial ligation are likely to be small, and large randomised trials unlikely to be conducted, observational studies at a national level are probably best suited to answer the question of whether high ligation is beneficial or detrimental to the patient undergoing anterior resection for rectal cancer, with regard to morbidity, especially anastomotic leakage [Citation4], as well as long-term outcomes such as systemic recurrence and overall survival. The Swedish Colorectal Cancer Registry [Citation5] has, since 2007, included the variable ‘level of arterial ligation’, which details the position of the tie used in the operation. However, this variable has hitherto not been formally evaluated. Therefore, we set out to validate this registry variable using operative charts as a reference.

Methods

Study design

All rectal cancer patients in Sweden have, since 1995, been continuously reported to the national Rectal Cancer Registry (as of 2007, the Swedish Colorectal Cancer Registry), administered by the Regional Oncological Centre (ROC) in each healthcare region. Data relating to the patient, surgery, postoperative course, final pathological assessment, and follow-up over a five-year period are recorded [Citation5]. For the sake of completeness, the ROC registers are continually checked against the National Cancer Registry, which receives notification of new cancer cases from both clinicians and pathologists.

In an effort to evaluate the effects of the ligation level on morbidity in cardiovascularly compromised patients, a national cohort study was designed, linking data from the Colorectal Cancer Registry with data from the Prescribed Drugs Registry [Citation6] by means of the national personal identity number [Citation7]. We selected the study population to reflect the common assumption that these patients would be more sensitive to a compromised visceral blood flow. All 2673 patients operated for rectal cancer by anterior resection during the period 2007–2010 were included, of whom 787 patients were registered for use of any of the following, prior to their operation: any antidiabetic drug, any anticoagulant drug (except drugs with indications for deep venous thrombosis or atrial fibrillation, e.g. warfarin), any nitroglycerin-based drugs. Operative charts were retrieved and scrutinised by two reviewers (M.R., surgical resident and P.B., surgical intern). A small number of cases showed a sufficiently high level of ambiguity regarding ligature level to necessitate expert help from a senior colorectal surgeon (J.R.). The regional ethical review board at Umeå University approved the study.

Arterial ligation

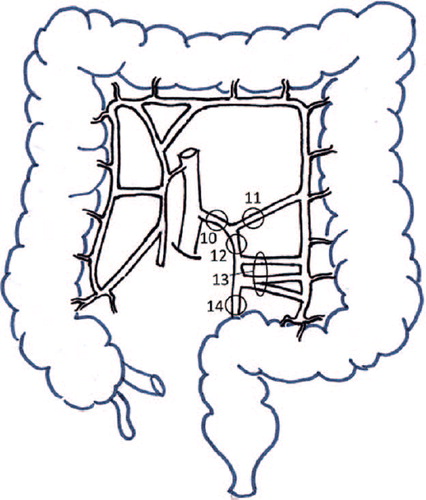

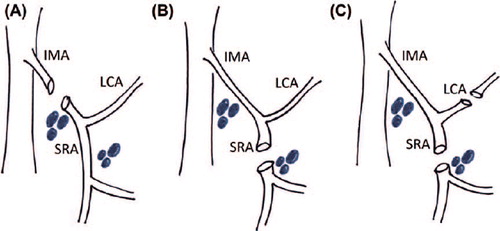

The possible different levels of arterial ligation are outlined in and . A high tie is defined as ligation of the IMA close to the aorta, proximal to the LCA, while a low tie is defined as ligation of the SRA, distal to the LCA. As low tie surgery sometimes forces the surgeon to sacrifice the LCA in order to alleviate tension on the anastomosis, the combination of SRA and LCA ligation may constitute a third ligation option. Furthermore, selective lymphadenectomy of the apical lymph nodes at the root of the IMA is not routinely used in Sweden, leading to the following definitions used in the current study ( and ):

High tie: Ligation of tie point 10, solely or in any combination.

Low tie: Ligation of tie points 12, 13 or 14, or any combination of these.

Combination tie: Ligation of tie point 11 with tie points 12, 13 or 14 (or any combination of the latter).

Figure 2. Levels of arterial ligation levels extracted from operative charts. (A) High tie; (B) Low tie; (C) Combination tie.

The few cases registered as tie point 11 solely were assumed to be combination ties. To create meaningful entities for research, the following complementary definitions have been introduced:

Functional high tie: High tie or combination tie.

Functional low tie: Low tie.

Oncologic high tie: High tie.

Oncologic low tie: Low tie or combination tie.

Thus, the functional entities are anatomically related to the degree of perfusion to be expected after the tie, allegedly being of importance, e.g. anastomotic leakage, while the oncologic entities may be more valid, e.g. systemic recurrence, due to better description of the extent of mesenterial resection.

Statistical analysis

The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive values (PPVs) and negative predictive values (NPVs) of functional high and low tie as well as oncologic high and low tie were computed using data from the operative charts as reference. Due to the dichotomous relationship between high and low tie, an important observation could be made in advance: specificity of a low tie equals the sensitivity of a high tie, and vice versa; PPV and NPV are similarly related. Finally, the level of agreement and Cohen's kappa were analysed using the standard formula [Citation8]. These estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were based on the binomial distribution, calculated using STATA 12.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

The original cohort consisted of 787 patients. Operative charts were retrieved for 782 patients, while five (0.6%) charts were missing. Of the former, 34 (4.3%) patients were excluded due to incorrect registration of the surgical procedure. Three patients underwent surgery where ligation of the IMA was compulsory (proctocolectomy or left hemicolectomy including rectal resection) and one patient was operated outside of the study period. Thus 744 (94.5%) patients remained for analysis.

Some clinical data for these patients are displayed in . Most patients were male, between the ages of 65 and 75 (median: 71, interquartile range: 66–77), and approximately two thirds were of ASA class I–II. The distribution of tumour stage was fairly even for stage I–III, whereas a much smaller proportion was classified as stage IV tumours. Almost half of the patients had no preoperative radiotherapy. About a third underwent partial mesorectal excision; a majority of patients had a covering stoma at the initial operation, while only a small proportion was operated laparoscopically. About one tenth of all patients developed symptomatic anastomotic leakage ().

Table I. Clinical data for 744 patients operated with anterior resection for rectal cancer in Sweden during 2007–2010.

shows the overall numbers of the ligation level, comparing the variables extracted from the operative charts from those of the registry, including the missing data.

Table II. Extracted versus registered tie levels in 744 patients operated with anterior resection for rectal cancer in Sweden in 2007–2010.

The sensitivity for functional high tie, by this count, equals 80.2%, with a specificity of 90.1%. PPV and NPV are 87.7 and 83.8%, respectively. Regarding the high oncological ties, the sensitivity and specificity were 81.2 and 88.6%, respectively, with a PPV of 83.2 and an NPV of 87.2%. In addition, the levels of inter-record agreement were 85.5% for functional and 85.6% for oncological tie, with kappa values of 0.70 and 0.71, respectively. All variables with corresponding CIs are shown in below, where the symmetry of the relationship can also be observed ().

Table III. Sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV with corresponding 95% CI, as well as level of agreement and Cohen's kappa for different levels of tie.

The retrieval of lymph nodes differed in the high and low tie groups, with a larger number of retrieved lymph nodes in the high tie groups. When stratifying functional ties the mean number of lymph nodes was 16.4 versus 15.0 when data was based on the operative charts, and 17.0 versus 14.6 according to the registry data. The corresponding values for oncologic ties were 16.2 versus 15.2, and 17.1 versus 14.6.

Discussion

This study shows that the arterial ligation level is a variable that is seldom missing in the Swedish Colorectal Cancer Registry. We consider the validity to be acceptable, taking into consideration how registration was performed and the number of hospitals involved.

A registry is only as good as its data entries. In similarity with all records relying on secondary sources, validation of the data within the registry is of utmost importance. The Swedish Colorectal Cancer Registry has on a number of occasions been evaluated by external researchers. In 1998 a fifth of the registry was assessed, showing less than 5% discrepancy [Citation5], and later studies have shown an acceptable degree of accuracy, even though certain postoperative complications, especially those not necessarily severe, such as wound infections, were underreported [Citation9]. Recently, the Swedish Rectal Cancer Registry, which later merged to form the Swedish Colorectal Cancer Registry, showed good validity for major abdominal surgery performed in 1995–1997 [Citation10].

One advantage of this study is the simplicity of the model. Hence, problems of misunderstandings are expected to be smaller. However, even though a proposed standardisation of the operative documentation exists [Citation11], the language used in practice is often vague, ambiguous and does not necessarily correlate to the anatomic and surgical relationships that it describes. Accordingly, the study could be influenced by information bias, with a misclassification bias being especially potent. Examples of suboptimal documentation include non-uniform naming of the arteries involved, lack of detail regarding the important steps of the procedure, and spatial descriptions sometimes given from the perspective of the surgeon, sometimes of the tissue and often without any clear reference point. Under the wrong circumstances, such language could at best be misinterpreted but, at worst, not be perceived as problematic, and hence not lead to a review by the more senior colorectal surgeon, in accordance with the study design. Furthermore, there is still no consensus agreement among colorectal surgeons when the IMA changes into the SRA in the nomenclature, and this may threaten the validity of the reference itself. In addition, the visceral vascular anatomy is variable, further increasing the difficulty of determining the correct nomenclature [Citation12,Citation13].

In this study, the results are calculated and presented as estimates of sensitivity, specificity, both PPVs and NPVs, level of agreement and Cohen's kappa. However, the relative shortage of validation studies of registries results in uncertainty as to how to present the results and no established standard seems to exist. Other studies have presented data as sensitivity, specificity and kappa values [Citation14], as extensively as this study [Citation15,Citation16], using sensitivity, specificity and predictive values [Citation17], with emphasis on the level of completeness [Citation18,Citation19] or with the help of PPV only [Citation20]. In our own field, Gunnarsson et al. [Citation9] described the validity of surgical data regarding colorectal cancers, comparing national, regional and local registers, using the relative frequency of errors and missed proportions.

In order to determine the statistical robustness of our estimates, calculations were performed with missing data attributed to different groups, in order to analyse extreme outcomes. However, when maximising and minimising the sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV, only a minor overall impact on both the point estimates and the confidence intervals was discerned. The PPV estimates varied between 80.7% and 88.3% for functional high tie and between 76.1% and 84.0% for oncologic high tie. The other parameters showed similar robustness, including the corresponding low tie. Therefore, the impact of missing values did not materially alter the conclusions derived from the current study.

The lack of accuracy of a registry is a consequence of human error and is often due to compromised institutional settings. In order to optimise surgical registries, the reporting of data from the clinic to the collecting authority needs to be improved. However, it is possible that the lack of accuracy reflects the surgeon's inability to fully understand the anatomy of the operation, and that the ambiguity of the vocabulary used to describe the operation is closely linked to this flawed anatomical understanding. Alternatively, surgeons do not find it necessary, important or prioritised to check and perhaps also recheck the operative charts of medical records or the data sent to the registries. Other possibilities include the use, e.g. of nurses for reporting the data, as they lack the operative experience of the surgeon and constitute yet another link in the chain of communication. In an effort to analyse the institutional effect, the PPVs for functional high tie were broken down at a hospital level, whereby major differences were revealed (data not shown). Sixteen of the 51 hospitals showed 100% PPVs for the aforementioned variable. Hence, substantially better validity is attainable in practice. A reasonable implication would be to focus the efforts to improve quality on certain hospitals, using other clinics as good examples.

Thirty-four (4.3%) operations were misclassified, the vast majority of which constituted Hartmann's procedure. To misclassify the operative procedure itself is an indicator of poor registration procedures, posing a problem regarding the validity of the registry. In addition, when the registry is used to identify anterior resections, the incidence of complications such as anastomotic leakage is artificially decreased since operations where no anastomosis is present dilute the true number of patients at risk.

In conclusion, the suboptimal validity of the Swedish Colorectal Cancer Registry regarding the level of vascular ligation might be problematic, when analyses with rare positive outcomes, such as bowel ischaemia, are conducted; likewise, validity issues may arise when differences in the outcomes are expected to be small, e.g. systemic recurrence. When performing such studies, it would be beneficial to collect data directly from the operative charts of the medical records in order to increase the chance of identifying clinically relevant differences.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Robert Johansson at the Oncological Centre, Umeå University, for invaluable assistance in providing registry data. We also acknowledge the contribution of Marie-Thérese Vinnars, in designing the vascular ligation drawings. The Cancer Research Foundation in Northern Sweden, Swedish Society of Medicine, Research Council Västernorrland County.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Kanemitsu Y, Hirai T, Komori K, Kato T. Survival benefit of high ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery in sigmoid colon or rectal cancer surgery. Br J Surg 2006;93:609–15.

- Titu LV, Tweedle E, Rooney PS. High tie of the inferior mesenteric artery in curative surgery for left colonic and rectal cancers: A systematic review. Dig Surg 2008;25:148–57.

- Lange MM, Buunen M, van de Velde CJ, Lange JF. Level of arterial ligation in rectal cancer surgery: Low tie preferred over high tie. A review. Dis Colon Rectum 2008; 51:1139–45.

- Rutegard M, Hemmingsson O, Matthiessen P, Rutegard J. High tie in anterior resection for rectal cancer confers no increased risk of anastomotic leakage. Br J Surg 2012;99: 127–32.

- Pahlman L, Bohe M, Cedermark B, Dahlberg M, Lindmark G, Sjodahl R, et al. The Swedish rectal cancer registry. Br J Surg 2007;94:1285–92.

- Wettermark B, Hammar N, Fored CM, Leimanis A, Otterblad Olausson P, Bergman U, et al. The new Swedish Prescribed Drug Register – opportunities for pharmacoepidemiological research and experience from the first six months. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Safety 2007;16:726–35.

- Ludvigsson JF, Otterblad-Olausson P, Pettersson BU, Ekbom A. The Swedish personal identity number: Possibilities and pitfalls in healthcare and medical research. Eur J Epidemiol 2009;24:659–67.

- Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas 1960;20:37–46.

- Gunnarsson U, Seligsohn E, Jestin P, Pahlman L. Registration and validity of surgical complications in colorectal cancer surgery. Br J Surg 2003;90:454–9.

- Jorgren F, Johansson R, Damber L, Lindmark G. Validity of the Swedish Rectal Cancer Registry for patients treated with major abdominal surgery between 1995 and 1997. Acta Oncol 2013;52:1707–14.

- Kolorektal cancer. Nationellt vårdprogram: Regional Oncological Centre, Umeå; 2008.

- Allison AS, Bloor C, Faux W, Arumugam P, Widdison A, Lloyd-Davies E, et al. The angiographic anatomy of the small arteries and their collaterals in colorectal resections: Some insights into anastomotic perfusion. Ann Surg 2010;251: 1092–7.

- García-Ruiz A, Milsom J, Ludwig K, Marchesa P. Right colonic arterial anatomy. Dis Colon Rectum 1996;39: 906–11.

- Malin JL, Kahn KL, Adams J, Kwan L, Laouri M, Ganz PA. Validity of cancer registry data for measuring the quality of breast cancer care. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002; 94:835–44.

- Pedersen CG, Gradus JL, Johnsen SP, Mainz J. Challenges in validating quality of care data in a schizophrenia registry: Experience from the Danish National Indicator Project. Clin Epidemiol 2012;4:201–7.

- Roberts CL, Ford JB, Lain S, Algert CS, Sparks CJ. The accuracy of reporting of general anaesthesia for childbirth: A validation study. Anaesth Intensive Care 2008; 36:418–24.

- Lain SJ, Roberts CL, Hadfield RM, Bell JC, Morris JM. How accurate is the reporting of obstetric haemorrhage in hospital discharge data?A validation study. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2008;48:481–4.

- Pedersen A, Johnsen S, Overgaard S, Soballe K, Sorensen HT, Lucht U. Registration in the Danish hip arthroplasty registry: Completeness of total hip arthroplasties and positive predictive value of registered diagnosis and postoperative complications. Acta Orthopaed Scand 2004; 75:434–41.

- Topp M, Langhoff-Roos J, Uldall P. Validation of a cerebral palsy register. J Clin Epidemiol 1997;50:1017–23.

- Lagergren K, Derogar M. Validation of oesophageal cancer surgery data in the Swedish Patient Registry. Acta Oncol 2012;51:65–8.