Abstract

Backgrounds. Eribulin is a non-taxane, microtubule dynamics inhibitor approved for the treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer (MBC) in Europe in March 2011.

Material and methods. For the purpose of an internal quality control, all patients with MBC treated with eribulin at Karolinska University Hospital were registered in a database. Clinical data were collected retrospectively for patients that were registered by August 2012 and safety and efficacy of eribulin were evaluated. Treatment toxicity including fatigue, neurotoxicity and infection was graded according to CTCAE v4.0. Objective response to treatment was investigated using routinely performed radiological assessments. When only clinical assessments were made, the evaluation of the treating physician was used. Furthermore, the efficacy of eribulin was investigated in different tumor subtypes.

Results. Forty-eight patients who received at least one cycle of eribulin were identified. Most patients were heavily pretreated with a median of 3 (range 1–7) previous chemotherapy lines prior to eribulin. Median patient age was 56 years (range 35–74). At the end of the analysis, 23 patients were alive and two were still treated with eribulin. No hypersensitivity reactions and no toxic deaths were seen. Fatigue grade 3–4 was observed in three patients (6.3%). One patient experienced grade 4 neurotoxicity. Grade 3–4 neutropenia was documented in 18.8%, and three patients were treated for a grade 3 infection. Interestingly, three individuals developed Herpes zoster reactivation. One patient responded to treatment with complete remission, while 33.3% had a partial response. 48% of all patients had a clinical benefit (objective response or stable disease for more than six months).

Conclusions. Eribulin administered outside of a clinical trial in patients with advanced breast cancer was safe and well tolerated. A clinical benefit was seen in half of the cases. No statistically significant differences in objective response or survival were observed between histopathological subgroups.

Antitumoral therapy for metastatic breast cancer (MBC) is today composed of endocrine treatment [for estrogen receptor (ER) positive disease], targeted therapy against HER2 and cytotoxic chemotherapy. Approved chemotherapy agents in first line for MBC are anthracyclines and taxanes, while capecitabine is approved for second line. Other drugs that have demonstrated activity in randomized clinical trials and are widely used include vinorelbine, platinum analogs and gemcitabine.

Eribulin is a microtubule inhibitor with a unique mechanism of action [Citation1,Citation2]. Preclinical studies of eribulin showed promising results in suppression of several human cancer cell lines [Citation3]. Phase I and II studies proved that eribulin had a tolerable toxicity profile and an anti-cancer activity, even in a population of heavily pretreated women [Citation4–9]. The phase III study EMBRACE, a multicenter, open-label, randomized trial, demonstrated a clinically and statistically significant improvement in overall survival (OS) in the eribulin treatment arm in comparison to treatment of physician's choice [Citation10]. It also showed that eribulin was well tolerated, with the majority of adverse events grading 1 or 2. Most common adverse events in the study were neutropenia, fatigue, nausea and peripheral neuropathy. The results of the EMBRACE study led to the approval of eribulin in Europe in March 2011 for the treatment of patients with MBC that have had a progression on two or more previous lines of chemotherapy, including a taxane- and an anthracycline-based regime, unless patients were not suitable for these agents [Citation11].

A subsequent multicenter phase III trial compared eribulin with capecitabine as first, second or third treatment line in patients with MBC after prior anthracycline and taxane-based therapy. The study failed to show a statistically significant benefit of eribulin in terms of progression-free survival (PFS) and OS. However, there was a clear trend for an OS benefit for eribulin (p = 0.056) and subgroup analyses suggest a survival benefit with eribulin in women with HER2-negative and triple-negative breast cancer [Citation12].

To date, little is known about the routine use of eribulin in patients outside of clinical trials. Four recent reports indicate efficacy and safety comparable to the randomized trials, with response rates ranging from 18% to 30% [Citation13–16]. Here, we present a retrospective, quality assurance analysis on the first 48 patients with MBC treated with eribulin at Karolinska University Hospital in Stockholm, Sweden.

Material and methods

Study objectives

The primary objective of the study was to investigate the efficacy and safety of eribulin in patients with MBC treated outside a clinical trial. Secondary objective was to explore the efficacy of eribulin in subgroups of patients identified according to ER, HER2 and tumor proliferation expression measured in primary tumors and in corresponding metastasis.

Patients and data collection

Patients treated with eribulin at the Oncology Department of Karolinska University Hospital were registered in a database by treating oncologists. The patients in this study were retrospectively identified using this registry and were crosschecked with the hospital chemotherapy registry. All patients having received at least one cycle of eribulin for MBC from March 2011 until August 2012 were included. None of these patients received eribulin within a clinical trial. The follow-up and data collection were completed in February 2013.

The patients were treated according to the approved indication and dosology for eribulin in MBC, with a dose of 1.4 mg/m2 eribulin mesylate administered intravenously on Days 1 and 8 of a 21-day cycle. Dose reductions were made according to the Summary of Product Characteristics for eribulin and the treating physician's judgment. Patients with HER2 amplified tumors received trastuzumab concomitantly with eribulin and patients with bone disease received bisphosphonates unless contraindicated for other reasons. Endocrine therapy was not given concomitantly and when used in the previous line of therapy it was terminated before start of eribulin. No patients were given primary prophylaxis with granulocyte colony stimulating factor, but secondary prophylaxis was used in selected cases with severe or extended neutropenia.

Patient data, including demographics, clinical and pathologic disease characteristics and type of previous chemotherapy treatment, eribulin dosage and number of received eribulin cycles were retrospectively retrieved using the patient records of the oncology department. Radiology reports and clinical assessments of the treating physician were used for efficacy evaluations. According to the institutional guidelines, imaging assessments were repeated with two- to three-month intervals and the same modality used at baseline was consistently used for future evaluations of response. As these patients were not treated within a clinical trial, Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST) was generally not applied. Adverse events were registered retrospectively by searching the physician and nurse reports as well as the relevant laboratory values and were quantified by the investigators according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4.0 [Citation17].

To further investigate the efficacy of eribulin in different tumor subtypes, a database of the Department of Cytology and Pathology at Karolinska University Hospital was used to collect data regarding tumor characteristics of the patient's primary tumor and corresponding relapse biopsy. In those cases where patients had more than one primary tumor, the primary tumor most likely to have caused the first examined metastases was chosen. When a non-clear correlation between primary tumor and metastasis was ascertained, the patient was excluded from this analysis. The institutional cut-off values of at least 10% positively stained cells for ER and progesterone receptor (PR) positivity were applied for this analysis. HER2 negative tumors were scored as 0 or + 1 by immunohistochemistry, while HER2 positive cases were + 2 or + 3 by immunohistochemistry and amplified by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Ki67 was defined as high when the fraction of positively stained cells was more than 20%, according to the cut-off value of the pathology laboratory at Karolinska Hospital.

All randomized phase II or III prospective trials of eribulin as well as the published retrospective studies on the efficacy and safety of eribulin were identified using PubMed searches (updated in March 2014). The search terms used were ‘eribulin’ and ‘breast cancer’ and the clinical studies were then manually selected from the results. For preliminary results of unpublished prospective trials, conference abstracts of the American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting and the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium of 2012–2013 were also searched.

Study approval was obtained from the local ethics committee of Karolinska Institute. All patients were appointed a specific study number and were made anonymous by removal of personal data from the database. The key/code lists were only available for the investigators.

Statistical analysis

OS and PFS were the primary efficacy endpoints. OS was defined as the time from first course of eribulin until death from any cause or last follow-up and PFS as the time from first course of eribulin until tumor progression or death. Patients still alive and without progression at last follow-up were censored for the purpose of OS and PFS analysis. Additional efficacy end-points were the objective response rate (ORR) defined as the sum of the obtained partial responses [Citation7] and complete remissions (CR) and the clinical benefit rate (CBR) the sum of PR, CR and stable disease (SD) maintained for at least six months. The efficacy end-points were investigated using the routinely performed radiological assessment at Karolinska University Hospital. When radiological assessment was not performed, clinical examination was the considered parameter for the efficacy evaluation. Prospectively defined side effects that were investigated in all patients for the safety evaluation included hypersensitivity reactions, fatigue, sensory neuropathy, neutropenia and infection. All hospital admissions and their cause during eribulin treatment were registered.

An exploratory analysis of the treatment efficacy was performed in subgroups of patients defined by clinical parameters or according to ER and HER2 status and Ki67 expression levels in primary tumor and corresponding metastasis.

OS and PFS were estimated by using Kaplan-Meier method and the subgroups were compared by log-rank test.

Results

Forty-eight patients with MBC that had received at least one course of eribulin were identified. Most patients were heavily pretreated with a median of three previous lines of chemotherapy prior to eribulin (range 1–7) (). The majority of patients (85%) had previously received adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Median age at treatment start was 56 years (range 35–74). At the end of follow-up (February 2013), the patients had received a median of seven courses of eribulin (range 1–21) while in two patients eribulin treatment was still ongoing.

Table I. Baseline characteristics of the 48 patients with metastatic breast cancer treated with eribulin.

Efficacy

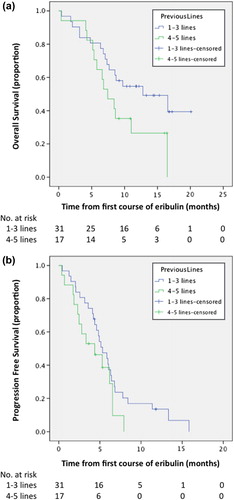

At the end of follow-up, 29 OS events and 42 PFS events were registered. Median OS was 8.9 months, [95% confidence interval (CI) 4.5–13 months]. Median PFS was 4.7 months (95% CI 4.2–6 months). Median OS was 12.8 and 6.5 months in patients who received from one to three and in patients who received ≥ 4 previous lines of chemotherapy for MBC, respectively (p = 0.06, by log-rank test) (). A non-significant difference of less than one month in PFS was seen between the afore-mentioned groups (5.3 vs. 4.4 months, p = 0.16 by log-rank test) ().

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meyer estimates of (a) overall survival (OS) and (b) progression-free survival (PFS) in 48 patients with metastatic breast cancer who received up to three versus ≥ 4 previous chemotherapies before treatment with eribulin at the Department of Oncology, Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm.

Twenty-two (46%) patients got a diagnosis of disease progression while nine (19%), 16 (33%) and one (2%) patients were diagnosed with SD, PR and CR, respectively. The ORR was 35% and CBR was 48%, respectively. ORR did not differ between patients that had previously received up to three or four or more previous chemotherapy lines for MBC (35% in both groups). The CBR was 54% and 35% in patients treated with one to three and with ≥ 4 previous chemotherapeutic regimens.

Safety

Predefined adverse events and hospital admissions after a total of 342 courses of eribulin were retrospectively documented and graded by the investigators (summarized in ). In general, treatment was well tolerated and no previously unreported complications were observed. The most common adverse event was sensory neuropathy (in most cases of grade 1) and the most common grade ≥ 3 adverse event was neutropenia. None of the patients experienced hypersensitivity reactions after eribulin. No deaths directly related to treatment were seen; however, four (8%) patients died due to disease progression while eribulin therapy was still ongoing. Although progressive disease was confirmed in all these cases, a possible contribution of treatment to the deterioration of the patients cannot be fully excluded. Nine hospital admissions were registered during eribulin treatment. The cause of admission was bacterial infection in five cases, two of which with neutropenia; pain in two cases, one of them because of Herpes zoster reactivation, the other due to metastatic disease; one case of dyspnea caused by malignant pleural effusion; and one case of dysphagia, probably by neurotoxicity as detailed below.

Table II. Eribulin treatment-related adverse events.

Four (8%) patients discontinued treatment because of toxicity, two because of liver function impairment and the remaining two because of fatigue and neurotoxicity, respectively. The latter developed severe dysphagia of unknown etiology, eventually leading to tracheotomy. Although there is an uncertainty whether this was an adverse effect of eribulin it was registered as a life threatening neurotoxicity (grade 4). Notably, before starting treatment with eribulin, this patient was on endocrine therapy and had no signs of neuropathy. She complained of dysphagia after two cycles of treatment but received a total of seven cycles of eribulin before she was admitted due to dysphagia.

Despite the high frequency of neutropenia, severe infections were uncommon (). Interestingly, three cases of Herpes zoster reactivation were documented – all based on clinical diagnosis – and were effectively treated with antiviral therapy.

Histopathological subgroups analysis of efficacy

The histopathological characteristics of the primary tumor and corresponding relapse are summarized in . For the purpose of an exploratory analysis, efficacy was investigated in subgroups of patients defined by the expression of ER, HER2 and Ki67 (). No statistically significant differences in objective response or survival were observed between the different tumor subtypes, probably owing to the low number of patients.

Table III. Histopathological characteristics of primary tumor and corresponding metastasis in 48 patients with breast cancer treated with eribulin.

Table IV. Efficacy analysis in subgroups of patients identified according to ER, HER2 and Ki67 expression.

ER, HER2 and Ki67 status information both in primary tumor and in matched metastasis were available in 39 (81%), 22 (46%) and 21(44%) of 48 patients, respectively. ER status changed from positive in primary tumor to negative in relapse in two patients, while no changes from negative to positive were registered. HER2 status changed, from positive to negative, in one patient. Ki67 changed in five patients, from low in primary tumor to high in metastasis in two cases and from high to low in three cases. No changes in the subgroup efficacy analysis were observed when the subgroups were defined according to ER, HER2 and Ki67 expression in the metastatic tissue (Supplementary Table I, to be found at online http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2014.973063).

Published data on randomized and retrospective studies on the efficacy of eribulin are detailed in .

Table V. Summary of published data on eribulin treatment in locally recurrent and metastatic breast cancer.

Discussion

Patients treated in clinical trials are highly selected and are often not representative of the general patient population. They are usually younger, have a better performance status and less comorbidity compared with the patients treated in routine practice after the drug in question has been approved [Citation18]. It is thus of importance that both efficacy and safety aspects are further studied in routinely treated cohorts of patients in order to define the place of newly approved cancer drugs in the therapeutic arsenal. Here, we present the results of a single center quality assurance project for eribulin in patients with MBC. The 48 patients studied were generally heavily pretreated but the therapy was well tolerated and beneficial for a significant proportion of the patients.

The efficacy of eribulin in this cohort was in line with the reported phase III studies. Median PFS was 4.7 months, compared with 3.7 months in EMBRACE [Citation10] and 4.1 months in the eribulin versus capecitabine trial. ORR was also higher (35%) compared to 12% and 11%, respectively, probably because the response evaluation in the current study was based on the assessment of the treating physician and was thus less strict than the RECIST criteria applied in the randomized trials. However, median OS was substantially lower (8.9 months compared to 13.1 and 15.9 months in the two phase III trials) presumably owing to the fact that the patients were not selected as in randomized trials. Patients that had received up to three previous chemotherapy lines for MBC had a clear trend to better OS, better PFS and CBR, motivating further studies of eribulin earlier in the course of MBC.

The reported analysis of efficacy in the different subgroups of patients was exploratory and was limited by the small number of patients in each group. As in previous studies [Citation12], patients with ER positive, HER2 negative and non-triple negative tumors had a better survival. However, the previously suggested higher activity of eribulin in triple negative tumors could not be confirmed in this study, as none of the five patients responded to treatment.

The tolerability of eribulin was comparable with the previously published data, with neutropenia and peripheral neuropathy being the most common clinically relevant side effects. It is noteworthy that three cases of Herpes zoster were reported, a side effect previously described as uncommon for eribulin [Citation11]. Longer experience with eribulin is required to clarify whether reactivation of Herpes zoster is more common than previously thought or if this was a chance finding in this cohort.

In summary, this retrospective analysis confirms the activity and safety of eribulin in MBC. It also highlights the need for further randomized studies to define the role of eribulin earlier in MBC as well as in early breast cancer. As with most chemotherapeutic agents, clinical indicators or novel biomarkers that could identify patients with a higher chance to benefit from treatment are needed.

Supplementary material available online

Supplementary Table I, to be found at online http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2014.973063).

ionc_a_973063_sm2246.pdf

Download PDF (111 KB)Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all treating physicians and the administrative personnel at the Oncology Department, Karolinska University Hospital for providing patient data to the eribulin registry. Supported by grants from the Cancer Society in Stockholm, Breast Cancer Theme Center (BRECT) at Karolinska Institutet, the Stockholm County Council and the Swedish Cancer Society.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Hamel E. Natural products which interact with tubulin in the vinca domain: Maytansine, rhizoxin, phomopsin A, dolastatins 10 and 15 and halichondrin B. Pharmacol Therapeut 1992;55:31–51.

- Jordan MA, Kamath K, Manna T, Okouneva T, Miller HP, Davis C, et al. The primary antimitotic mechanism of action of the synthetic halichondrin E7389 is suppression of microtubule growth. Mol Cancer Therapeut 2005;4:1086–95.

- Towle MJ, Salvato KA, Budrow J, Wels BF, Kuznetsov G, Aalfs KK, et al. In vitro and in vivo anticancer activities of synthetic macrocyclic ketone analogues of halichondrin B. Cancer Res 2001;61:1013–21.

- Goel S, Mita AC, Mita M, Rowinsky EK, Chu QS, Wong N, et al. A phase I study of eribulin mesylate (E7389), a mechanistically novel inhibitor of microtubule dynamics, in patients with advanced solid malignancies. Clin Cancer Res 2009;15:4207–12.

- Tan AR, Rubin EH, Walton DC, Shuster DE, Wong YN, Fang F, et al. Phase I study of eribulin mesylate administered once every 21 days in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2009;15:4213–9.

- Cortes J, Vahdat L, Blum JL, Twelves C, Campone M, Roche H, et al. Phase II study of the halichondrin B analog eribulin mesylate in patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer previously treated with an anthracycline, a taxane, and capecitabine. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:3922–8.

- Vahdat LT, Pruitt B, Fabian CJ, Rivera RR, Smith DA, Tan-Chiu E, et al. Phase II study of eribulin mesylate, a halichondrin B analog, in patients with metastatic breast cancer previously treated with an anthracycline and a taxane. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:2954–61.

- Aogi K, Iwata H, Masuda N, Mukai H, Yoshida M, Rai Y, et al. A phase II study of eribulin in Japanese patients with heavily pretreated metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol 2012;23:1441–8.

- McIntyre K, O’Shaughnessy J, Schwartzberg L, Gluck S, Berrak E, Song JX, et al. Phase 2 study of eribulin mesylate as first-line therapy for locally recurrent or metastatic human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2014;146:321–8.

- Cortes J, O’Shaughnessy J, Loesch D, Blum JL, Vahdat LT, Petrakova K, et al. Eribulin monotherapy versus treatment of physician's choice in patients with metastatic breast cancer (EMBRACE): A phase 3 open-label randomised study. Lancet 2011;377:914–23.

- Halaven: EPAR – Product Information European Medicines Agency 2014 [updated 2014 Feb 7, 23/03/2014]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/002084/WC500105112.pdf. (cited 2014 March 23).

- Kaufman PA, Awada A, Twelves C, Yelle L, Perez EA, Wanders J, et al. A phase III, open-label, randomized, multicenter study of eribulin mesylate versus capecitabine in patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer previously treated with anthracyclines and taxanes. [S6-6] Cancer Res2012;72(24 Suppl).Abstract.

- Ramaswami R, O’Cathail SM, Brindley JH, Silcocks P, Mahmoud S, Palmieri C. Activity of eribulin mesylate in heavilypretreated breast cancer granted accessvia the Cancer Drugs Fund. Future Oncol 2014;10:363–76.

- Hattori M,Fujita T,Sawaki M,Kondo N,Horio A,Ushio A, et al.[Clinical efficacy and safety assessment of eribulin monotherapy in patients with metastatic breast cancer – a single-institute experience]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 2013; 40:737–41.

- Poletti P, Ghilardi V, Livraghi L, Milesi L, Rota Caremoli E, Tondini C. Eribulin mesylate in heavily pretreated metastatic breast cancer patients: Current practice in an Italian community hospital. Future Oncol 2014;10:233–9.

- Gamucci T, Michelotti A, Pizzuti L, Mentuccia L, Landucci E, Sperduti I, et al. Eribulin mesylate in pretreated breast cancer patients: A multicenter retrospective observational study. J Cancer 2014;5:320–7.

- Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v.4.0 (CTCAE). National Cancer Institute; 2009 [14 March 2014]. Available from: http://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm. (cited 2014 March 14).

- Unger JM, Barlow WE, Martin DP, Ramsey SD, Leblanc M, Etzioni R, et al. Comparison of survival outcomes among cancer patients treated in and out of clinical trials. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014;106:dju002.