Abstract

Background. For Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), the International Prognostic Index is the major tool for prognostication and considers an age above 60 years as a risk factor. However, there are several indications that increasing age is associated with more biological complexity, resulting in differences in DLBCL biology depending on age.

Methods. We conducted a registry-based retrospective cohort study of all Swedish DLBCL patients diagnosed 2000–2013, to evaluate the importance of age at diagnosis for survival of DLBCL patients.

Results. In total, 7166 patients were included for further analysis. Survival declined for every 10-year age group and every age group above the age of 39 had a statistically decreased survival compared to the reference group of 20–29 years. In an analysis of relative survival, and in a multifactorial model adjusted for stage, ECOG performance status, serum lactate dehydrogenase and involvement of extranodal sites, each age group above age 39 had a significantly higher risk ratio (p = 0.01) compared to the reference group.

Conclusion. This is one of the largest population-based studies of DLBCL published to date. In this study, age persisted as a significant adverse risk factor for patients as young as 40 years, even after adjustment for other risk factors.

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is one of the most common subtypes of lymphoma, accounting for about 30–40% of all cases [Citation1].

DLBCL is aggressive, with poor prognosis without adequate treatment. For some time a combination of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (CHOP) has been the standard treatment and survival rates below 50% have been reported [Citation2]. With addition of the monoclonal antibody rituximab (R-CHOP), the survival rate increased substantially, both in the elderly population [Citation3] and to an even higher degree in a younger population [Citation4].

Prediction of survival and stratification of therapy for DLBCL patients is currently based predominantly upon the International Prognostic Index (IPI), initially described in1993. IPI incorporates five clinical variables, each one individually associated with survival in DLBCL; Ann Arbor stage III–IV, elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase (S-LDH), extranodal involvement of more than one site, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) of 2 or higher, and age above 60 years [Citation5]. However, several attempts to improve the IPI in the rituximab era have been made [Citation6]. One possible disadvantage of IPI is the use of a cut-off age of 60 years as a risk factor [Citation5]. Although several studies only address old age as a relevant risk factor for DLBCL [Citation5,Citation7], recent data regarding follicular lymphoma and Hodgkin's lymphoma (HL) suggest that there is a survival difference based upon age stratification for patients younger than 60 years [Citation8,Citation9].

For DLBCL, there are several indicators of a biological difference in different age groups and many features are reported to be associated with poor prognosis in DLBCL, such as the activated B-cell (ABC) subtype, BCL2 expression, or cytogenetic complexity, all of which increase in relation to age at diagnosis [Citation10–12]. There are thus several indications that aging may be important for lymphoma biology.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the importance of age at diagnosis for survival of DLBCL patients by using data from the Swedish Lymphoma Registry (SLR) covering the entire Swedish population. Possible explanations for the observed survival differences between different age groups were specifically addressed and additionally whether the introduction of rituximab had had effects on survival on a population basis.

Methods

Lymphoma Registry

The Swedish Cancer Registry was founded in 1958 and contains information from all patients diagnosed with cancer in Sweden. Pathologists are obliged to report all pathology specimens classified as malignant and the responsible clinical physicians report all patients with newly diagnosed cancer. The Swedish Cancer Registry contains information about date of diagnosis, type of cancer and date of death, but does not include details about the disease, i.e. stage, prognostic factors or treatment. In order to increase the quality control and evaluation of effects, the Swedish Lymphoma Group initiated the SLR in the year 2000.

The SLR gathers additional information about lymphomas, e.g. stage and IPI, and since 1 January 2007, also collects information about first-line treatment. However, the registry does not include information about treatment outcome for the entire study period, comorbidities or cause of death. Nor are children under the age of 16 and persons aged 16–19 treated at a pediatric ward included in the registry. Incidentally found cases, where the diagnosis was determined at autopsy, are also not included. The SLR covers approximately 95–97% of all lymphoma cases in Sweden, compared to the compulsory Swedish Cancer Registry [Citation13].

Study population

The study population included all patients diagnosed with DLBCL-NOS and diffuse non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphoma (ICD-O3: 96743, 96803, 96833, 96843), in Sweden from 1 January 2000 to 1 November 2013, and included in the SLR. (The SLR classifies lymphomas according to ICD-O3 and no further sub-classification of certain lymphomas are included). Patients diagnosed at an age younger than 20 (n = 13) were excluded from further analysis due to incomplete registry of this age group, as described above. The data collected included: year of diagnosis, age, gender, Ann Arbor stage, ECOG PS, extranodal sites, S-LDH, IPI and age-adjusted IPI (aaIPI). In 28 cases a reliable date of diagnosis was missing and they were therefore excluded from further analysis, leaving 7166 patients in the study. Prior to 1 January 2007, only incomplete data on treatment was available. However, there have been regional and national guidelines for the treatment of DLBCL during the study period. The recommended treatment was initially CHOP or CHOP-like (e.g. CHOEP, with the addition of etoposide to the CHOP regiment) and from 2005 rituximab was included in the national guidelines, with the recommendation of R-CHOP or R-CHOP-like treatment to all patients. Prior to this, rituximab was predominantly administered in clinical trial settings. Data on survival status were obtained from the Swedish Population Registry.

Ethics

This study was conducted in accordance with the rules of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local ethical review board at Uppsala University, which waived written consent due to the fact that all data retrieved from the SLR was anonymized.

Statistical analysis

Observed overall survival was calculated from date of diagnosis until last follow-up (as of 4 December 2013) or death. Survival curves were estimated according to the Kaplan-Meier method and the associated log-rank tests were used to examine survival disparities between different cohorts of the study population. Relative survival (RS) analysis was used as an additional method to measure DLBCL survival. RS is a commonly used method for capturing net survival in population-based cancer studies, where it computes mortality directly or indirectly correlated to the disease without requiring data about actual cause of death [Citation14]. In contrast to observed overall survival, which takes into consideration all deaths regardless of cause and gives a crude measurement of survival, RS can be expressed as a ratio between observed survival in the study population and the expected survival in a comparable group from the general population. Data regarding the reference population was extracted from the database http://www.mortality.org. For the computation of RS, the relsurv R package was used.

For evaluation of the prognostic impact of clinical risk factors an RS regression model according to the maximum likelihood method was used and expressed as a risk ratio (RR) [Citation15]. A test for equal proportions was performed with χ2. All statistical analyses were performed using the R statistical program version 2.14.2 (http://www.r-project.org). Probabilities with a p-value of less than 0.05 were judged as significant.

Results

Survival in different age groups

We identified 7166 patients with DLBCL between 1 January 2000 and 1 November 2013. The mean age at diagnosis was 68 years (range 20–105 years, interquartile range 60–79 years). The oldest patient diagnosed (at 105 years) was excluded from further analysis due to incomplete clinical data. Clinical characteristics for remaining patients are summarized in . Increasing numbers of patients were diagnosed with DLBCL as age increased, up until the age of 80, after which the actual number declined. However, the age-adjusted incidence rate increased until the age of 89 years at diagnosis.

Table I. Clinical characteristics of DLBCL in Sweden 2000–2013.

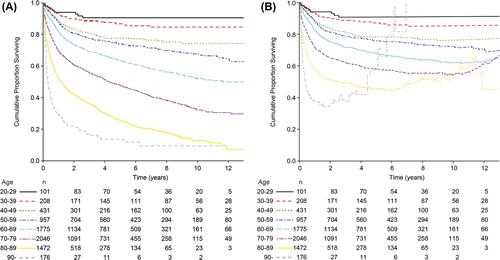

After stratification of age at diagnosis into age groups of 10 years, we found that survival declined for every 10-year age group (), although this was not statistically significant between the age groups 20–29 and 30–39 years (p = 0.4) and between the age groups 40–49 years and 50–59 years (p = 0.0591), however there was a significant difference between age groups 30–39 years and 40–49 years (p = 0.008) and between the age groups 30–39 years and 50–59 years (data not shown). Further, there was a significant difference in the observed overall survival between each age group for patients older than 50 years. Analysis of RS confirmed a decline for each respective age group ().

Effect of the introduction of rituximab

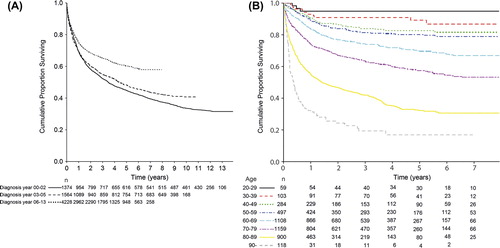

Due to incomplete registry data regarding treatment prior 2007, we divided the study period into three time periods depending on the introduction of rituximab. Prior to 2003, rituximab was only used in clinical studies for a minority of patients. Between 2003 and 2005 rituximab was gradually introduced mostly in clinical trial settings, and from May 2005 rituximab was finally included in the national treatment guidelines currently employed. In terms of a population-based analysis, the addition of rituximab significantly improved observed overall survival (). Also, when analysis was limited to the time period from 2006 and onwards, the higher survival rates for younger age groups, as described above, persisted ().

Analysis of available registry data regarding treatment revealed that more than 2300 patients were known to have been given a CHOP containing regimen (intention to treat) in combination with rituximab. The proportions of patients treated with R-CHOP alone and with the addition of etoposide (R-CHOEP) were examined with a χ2-test and did not differ significantly between the age groups 20–69 years of age ().

Clinical characteristics in relation to age

There was a higher proportion of patients with stage I–II disease in the lower age groups. Furthermore, the younger patients had better ECOG PS and a larger proportion with normal S-LDH levels compared to older patients, but the proportion of cases with different ECOG PS did not differ between age groups 20–69 years old (χ2-test; p > 0.9). There was no difference in the proportions of patients with extranodal engagement.

In total, only 487 patients (6.8%) were diagnosed with IPI 0, whereas 1777 (24.8%), 1967 (27.4%), 1703 (23.8%), 945 (13.2%) and 240 (3.3%) patients were diagnosed with IPI 1–5 respectively. For aaIPI, the number of patients in group 0–3 were 1764 (24.6%), 2211 (30.8%), 2199 (30.7%) and 945 (13.2%), respectively. When the population was stratified according to age into 10-year age groups, there was an increase in IPI with increasing age, with a distinct threshold at the age group 60–69 years of age. Naturally, all patients above 60 years of age are assigned one more point to the IPI score. This is overcome with aaIPI, even though aaIPI 0 was assigned to a larger proportion in the younger age groups. Both IPI and aaIPI had a significant impact on survival in this population-based cohort study, and the impact persisted after introduction of rituximab ().

In order to further analyze the impact of age as an independent factor on survival, RS RRs were analyzed in a multifactorial model adjusted for stage, ECOG PS, S-LDH and extranodal sites. Each 10-year age group above the age of 39 had a significantly higher relative RR () compared to the age group 20–29 years old. However, for patients diagnosed at an age older than 90 years and who survived the initial treatment, the RS increased toward the RS of the reference population, which is reflected in the rising line in and the outlying RR.

Table II. Relative risk ratio (RR) of DLBCL mortality in Sweden 2000–2013.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is one of the largest thoroughly population-based series of DLBCL published so far [Citation13,Citation16–18]. Despite the limitations of the study, the absence of information about treatment prior to 1 January 2007, and the lack of central pathology review, which is not feasible in a cohort of this size, the sheer size of our study population contributes to a substantial number of patients in the lower age range. Therefore, our study can specifically address the significant importance of age in all age groups when it comes to survival of DLBCL.

Historically, several studies of DLBCL have focused on age in terms of young versus old and treated old age as a risk factor [Citation3,Citation5,Citation19,Citation20], whilst some studies have been aimed at a younger population [Citation4]. However, these studies treat age as a continuous variable, and in the case of significance of survival differences, age is dichotomized with an arbitrary cut-off. The most famous perhaps being the delineation of patients over and under 60 years, which is used in the IPI [Citation5].

By the approach of dividing the population in age groups of 10 years, we were able to distinguish survival differences even for several age groups younger than 60 years. This is in line with other studies regarding other types of lymphomas. In one population-based Swedish study on HL, there was a significant survival difference between the age groups ‘below 50 years’, ‘51–65 years’ and ‘above 66 years’ [Citation9]. In another study regarding HL, based on the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database 1973–2004, survival differences were detected between age groups younger than 60 years of age [Citation21]. For follicular lymphoma, recent data presented a 10-year survival difference between patients ‘< 40 years’ and ‘41–59 years’ [Citation8], and in a large SEER-based material of several lymphoma types, there seems to be a survival difference between patients younger than 65 years of age [Citation22]. Even though the SEER-study incorporated many lymphoma entities, DLBCL is one of the most common lymphoma types and a survival difference between different age groups for DLBCL-patients could be reflected in the entire population [Citation1,Citation22]. In a recently published article including 3073 patients diagnosed with DLBCL between 2000 and 2010, Zhou et al. proposed a different scoring system for IPI where age was given a higher impact on total IPI-score. However, they pooled age into 20-year age groups, resulting in age groups of 40–60 years, 60–75 years and > 75 years. In contrast, we divided the cohort into 10-year age groups and found a significant survival difference between all 10-year age groups older than 40 years.

In younger age groups we found a higher percentage with low stage disease, a higher percentage with normal S-LDH and a higher proportion with low ECOG PS. This is reflected in the higher proportion of patients with low aaIPI and IPI among the younger age groups. All of these are known risk factors for DLBCL survival and are (with the exception of extranodal status) partly responsible for the survival differences between the different age groups, as was found in the multifactorial RS regression model (). However, after adjustment for risk factors incorporated in the IPI, age groups older than 40 years retained a significantly poorer survival compared to the age group 20–29 years old, even though there was no statistically significant difference in terms of the proportions of different ECOG PS between the age groups.

Therefore the cause of the shorter survival with increasing age is still unknown, although recent studies have found that biological factors associated with a worse prognosis for DLBCL are increased at higher age [Citation10–12].

DLBCL is, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO) classification of 2008, already divided into distinct entities, e.g. primary mediastinal DLBCL, primary DLBCL of the central nervous system, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) positive DLBCL of the elderly etc. All of these are included in the present study and may influence the results. However, DLBCL is probably an even more heterogeneous group of diseases and the etiology and clinical course might vary between the different groups. One example is the recently described subgroup of patients with DLBCL and follicular lymphoma with IRF4 translocations affecting predominantly children and young adults [Citation23]. Patients with IRF4 translocations had more often DLBCL of the germinal center (GC) subtype and an indolent low-stage disease. In total, the authors found IRF4 translocations in less than 5% of their population but it is not clear how many young adults there were in the entire group. The proportion of this indolent group might be higher in our younger population contributing to the better outcome, but cannot be the only explanation for the survival difference.

It has also been described that the non-GC subtype increases with age and these patients have a worse prognosis. After the introduction of rituximab, the difference is less clear and divergent results have been presented, with a tendency for a more beneficial effect of rituximab in the non-GC subtype [Citation24]. However, in our study the survival difference between young and old persisted after the introduction R-CHOP.

Another reason for the poorer survival in the elderly may be that elderly patients have more co-morbidities which makes effective treatment more difficult to pursue. In our study, the oldest patients were also included, but very few above the age of 85 were treated with curative intent (as is reflected among patients older than 80 years, treated after 1 January 2007, in the decline of proportions that received R-CHOP; ). Elderly patients have been found to have more toxicity and the treatment is more often prematurely ended due to this reason [Citation25]. The increased toxicity in elderly could however not explain the survival differences below the age of 60, since there was only a minor fraction not treated with R-CHOP, and R-CHOP usually is well-tolerated in younger patients.

In the present study we could also confirm, at population level, the benefit of the introduction of rituximab on the survival of DLBCL patients. Corresponding results have been presented from British Columbia [Citation26] with the same increment in survival.

In summary, we revealed significant differences in survival even among age groups younger than 60 years. Age persisted as a significantly adverse risk factor for patients as young as 40 years, even after adjustment for other risk factors. Although older age most certainly is a continuous negative prognostic variable, it is more practicable to divide age into certain age groups and specify an average increase in risk for each respective age group. Perhaps it is time to adjust age categories in IPI down to an age of 40 years [Citation6] considering that some of the younger age groups perhaps may benefit from a more intense treatment. However, the proposed 10-year age groups and their respective risk score in IPI must be evaluated in an independent DLBCL cohort.

Declaration of interest: This work was supported by the County Council of Uppsala, Sweden, and the Lions Cancer Research Foundation, Uppsala University Hospital, Uppsala, Sweden. The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, et al. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues, 4th ed. Lyon: WHO; 2008. p. 439.

- Fisher RI, Gaynor ER, Dahlberg S, Oken MM, Grogan TM, Mize EM, et al. Comparison of a standard regimen (CHOP) with three intensive chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med 1993; 14:1002–6.

- Coiffier B, Lepage E, Briere J, Herbrecht R, Tilly H, Bouabdallah R, et al. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2002;4:235–42.

- Pfreundschuh M, Kuhnt E, Trumper L, Osterborg A, Trneny M, Shepherd L, et al. CHOP-like chemotherapy with or without rituximab in young patients with good-prognosis diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma: 6-year results of an open- label randomised study of the MabThera International Trial (MInT) Group. Lancet Oncol 2011;11:1013–22.

- A predictive model for aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. The International Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Prognostic Factors Project. N Engl J Med 1993;14:987–94.

- Zhou Z, Sehn LH, Rademaker AW, Gordon LI, Lacasce AS, Crosby-Thompson A, et al. An enhanced International Prognostic Index (NCCN-IPI) for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated in the rituximab era. Blood 2014; 123:837–42.

- Varga C, Holcroft C, Kezouh A, Bucatel S, Johnson N, Petrogiannis-Haliotis T, et al. Comparison of outcomes among patients aged 80 and over and younger patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A population based study. Leuk Lymphoma 2014;55:533–7.

- Lobetti-Bodoni C, Rancoita PM, Montoto S, Lopez- Guillermo A, Conconi A, Coutinho R, et al. The importance of age in prognosis of follicular lymphoma: Clinical features and life expectancy of patients younger than 40 years. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts 2011;21:1593.

- Sjoberg J, Halthur C, Kristinsson SY, Landgren O, Nygell UA, Dickman PW, et al. Progress in Hodgkin lymphoma: A population-based study on patients diagnosed in Sweden from 1973–2009. Blood 2012;4:990–6.

- Mareschal S, Lanic H, Ruminy P, Bastard C, Tilly H, Jardin F. The proportion of activated B-cell like subtype among de novo diffuse large B-cell lymphoma increases with age. Haematologica 2011;12:1888–90.

- Thunberg U, Amini RM, Linderoth J, Roos G, Enblad G, Berglund M. BCL2 expression in de novo diffuse large B-cell lymphoma partly reflects normal differences in age distribution. Br J Haematol 2009;6:683–4.

- Klapper W, Kreuz M, Kohler CW, Burkhardt B, Szczepanowski M, Salaverria I, et al. Patient age at diagnosis is associated with the molecular characteristics of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood 2012;8:1882–7.

- Szekely E, Hagberg O, Arnljots K, Jerkeman M. Improvement in survival of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in relation to age, gender, IPI and extranodal presentation: A population based Swedish Lymphoma Registry study. Leuk Lymphoma 2014;55:1838–43 .

- Ederer F, Axtell LM, Cutler SJ. The relative survival rate: A statistical methodology. Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 1961;6:101–21.

- Pohar M, Stare J. Relative survival analysis in R. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2006;3:272–8.

- Lee L, Crump M, Khor S, Hoch JS, Luo J, Bremner K, et al. Impact of rituximab on treatment outcomes of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A population-based analysis. Br J Haematol 2012;4:481–8.

- Jayasekara H, Karahalios A, Juneja S, Thursfield V, Farrugia H, English DR, et al. Incidence and survival of lymphohematopoietic neoplasms according to the World Health Organization classification: A population-based study from the Victorian Cancer Registry in Australia. Leuk Lymphoma 2010;3:456–68.

- Hasselblom S, Ridell B, Nilsson-Ehle H, Andersson PO. The impact of gender, age and patient selection on prognosis and outcome in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma – a population-based study. Leuk Lymphoma 2007;4:736–45.

- Pfreundschuh M, Schubert J, Ziepert M, Schmits R, Mohren M, Lengfelder E, et al. Six versus eight cycles of bi-weekly CHOP-14 with or without rituximab in elderly patients with aggressive CD20 + B-cell lymphomas: A randomised controlled trial (RICOVER-60). Lancet Oncol 2008;2:105–16.

- Lin TL, Kuo MC, Shih LY, Dunn P, Wang PN, Wu JH, et al. The impact of age, Charlson comorbidity index, and performance status on treatment of elderly patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Ann Hematol 2012;91: 1383–91.

- Brenner H, Gondos A, Pulte D. Ongoing improvement in long-term survival of patients with Hodgkin disease at all ages and recent catch-up of older patients. Blood 2008; 6:2977–83.

- Pulte D, Jansen L, Gondos A, Emrich K, Holleczek B, Katalinic A, et al. Survival of patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma in Germany in the early 21st century. Leuk Lymphoma 2013;5:979–85.

- Salaverria I, Philipp C, Oschlies I, Kohler CW, Kreuz M, Szczepanowski M, et al. Translocations activating IRF4 identify a subtype of germinal center-derived B-cell lymphoma affecting predominantly children and young adults. Blood 2011;1:139–47.

- Nyman H, Jerkeman M, Karjalainen-Lindsberg ML, Banham AH, Leppa S. Prognostic impact of activated B-cell focused classification in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients treated with R-CHOP. Mod Pathol 2009;8:1094–101.

- Boslooper K, Kibbelaar R, Storm H, Veeger NJ, Hovenga S, Woolthuis G, et al. Treatment with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisolone is beneficial but toxic in very elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A population-based cohort study on treatment, toxicity and outcome. Leuk Lymphoma 2014;55:526–32.

- Sehn LH, Donaldson J, Chhanabhai M, Fitzgerald C, Gill K, Klasa R, et al. Introduction of combined CHOP plus rituximab therapy dramatically improved outcome of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in British Columbia. J Clin Oncol 2005;22:5027–33.