Abstract

Background. Chemotherapy and targeted drugs are important tools in the treatment of malignant diseases. A number of the planned treatments are cancelled late which is a great challenge for the clinic to minimize in order to prevent the risk for misused resources. The aim of this study was to analyze the frequency and reasons for late (<48 hours) cancellations and also to get an overview of all intravenous medical anti-cancer treatment at the clinic.

Material and methods. During four weeks in October 2010 all patients with intravenously administered chemotherapy and/or targeted drugs were registered at the Department of Oncology, Karolinska University Hospital. The survey comprehends the vast majority of all such treatment for solid tumors in adult patients in the Stockholm region with two million inhabitants. All bookings and late cancellations including their reasons were recorded. Diagnoses, treatment indication, line of treatment and survival, in particular short term survival, were analyzed.

Results. Almost 3000 bookings for 1460 patients were included and 13% were cancelled late. Patient detoriation was the dominating cause for late cancellation in patients with palliative treatment (59%), while hematological toxicity was most common in the adjuvant group (42%). The most common treatment indication was palliative (62%). Of the palliative treatments, 95% where given in the first to third treatment line. Breast cancer (31.9%) and colorectal cancer (29.9%) were the two most common diagnoses. Seventy-one patients (4.9%) died within two months after the treatment.

Conclusion. A more careful selection and monitoring of the patients might reduce the number of late cancellations due to patient detoriation. To record performance status (PS) as a routine for all patients might be helpful in that process. If the number of late cancellations could be reduced, resources at the clinic could be used more efficiently.

Medical treatment with chemotherapy and targeted drugs is one of the cornerstones in the treatment of malignant disease. With the large number of patients that comes every day to the clinic for such therapy the process needs to be effective. A number of planned treatments are cancelled late which creates a challenge to the effectiveness. In order to describe the size of the problem at the clinic and to analyze the reasons why a treatment was cancelled late, this study was launched. A further aim was to get a full view of all intravenous treatments with chemotherapy and targeted drugs and to categorize them in diagnoses, indications and in the case of palliative treatment also in treatment line. It is frequently stated that treatment is maintained too long in the palliative setting and that chemotherapy is administered even shortly before death. This might cause adverse effects without any gain in survival or quality of life (QoL). To address this question, survival was analyzed.

Stockholm, with a population of approximately two million inhabitants, has one oncological clinic only, the Department of Oncology at Karolinska University Hospital. The clinic is operating in three different hospitals, Danderyd Hospital (DH), Radiumhemmet in Solna (RH) and South General Hospital (SH). The clinic has four 24-hours wards with all together 72 beds and four-day care units with the capacity to treat approximately 150 patients per day, Monday through Friday. Hematological malignancies are treated at the Department of Hematology and pediatric malignancies at the Department of Pediatrics. Thus, these malignancies are not included in this survey. Some patients with lung cancer, mainly those not given radiotherapy, are treated at the Department of Respiratory Medicine and Allergy. The number of patients treated in private institutions is low. Thus, this analysis includes the large majority of adult patients treated for solid tumors in Stockholm. All planned and administered treatments of chemotherapy and targeted drugs during four weeks in October 2010 at the Department of Oncology were included. All data were collected from the medical record within the framework of an administrative survey, thus, no informed consent from the patients or approval from ethical committee was needed.

Material and methods

All patients that were planned to receive an intravenous treatment with chemotherapy and/or targeted drugs during a four-week period in October 2010 were registered in this survey. Patients with oral treatment only were not included. The patients were identified from the booking-lists in the computerized medical record 48 hours prior to the planned treatment and again on the treatment day. With these two registrations it was possible to identify late cancellations. From the medical record information about the diagnoses, treatment indication, previous treatment, age and sex of the patients were collected. Furthermore, the treatment regimen including the individual drugs were also recorded. The patient's identity was replaced with a special code number for anonymity. The diagnoses were grouped according to the administrative organization of the clinic. The gastro-intestinal cancer group (GI-cancer) was the largest and included gastric, pancreatic, biliary, gallbladder, intrahepatic bile duct, small intestine, colorectal and anal cancer. This group also included patients with neuroendocrine tumors (NET). The second largest group was breast cancer which also included sarcomas. The head, neck and chest cancer (HNC-cancer) constituted the third largest group including ear, nose and throat cancer, lung cancer, esophageal cancer, thyroid cancer, CNS-tumors and cancer of unknown primary (CUP). The fourth and fifth groups were gynecological and urological cancer, respectively.

The treatment indications were divided in three categories. 1) Curative treatment: patients with known tumor where the intent is curative. This category includes curative, neo-adjuvant and down-staging treatment. In this group concomitant radiotherapy most frequently was applied. 2) Adjuvant therapy: patients with no detectable tumor left after previous treatment. The aim of adjuvant therapy is to increase overall survival. 3) Palliative therapy: Patients with known tumors where cure is not possible and the purpose is to improve QoL and/or survival. A booking was defined as one planned day of treatment. A cycle was defined as one treatment over one or more days of treatment according to the treatment protocol. A patient was defined as the physical individual. Thus, one patient could have several bookings and cycles during the four-week period. A late cancellation was defined as a booking that was cancelled later than 48 hours prior to the actual treatment. The time was chosen because with an earlier cancellation there might be possible to call and treat another patient, which is more complicated during the two final days. The causes of cancellations were classified in five categories. 1) Hematological toxicity: i.e. leucopenia, thrombocytopenia, neutropenia or anemia. 2) Other toxicity: caused by previous therapy, e.g. liver, kidney or skin toxicity. 3) Patient's choice: e.g. the patient preferred to reschedule a booking. 4) Administrative reasons: due to lack of routines at the clinic, e.g. lack of communication between the staff and the patients and/or their relatives so that time or date was misinterpreted, or if the pharmacy could not deliver in time. 5) Detoriated performance status: The patient did not feel well, suffered from severe fatigue or symptom progression. Detoriated performance status was interpreted by reading the medical record. The distribution of treatment regiments in the three different hospitals was recorded and the differences were analyzed. Survival was analyzed two months after the study period, at the end of the year 2010 and again six and 12 months later. All data were collected and organized to a database created in the software program Filemaker Pro 9.0. Survival was described by using the Kaplan–Meier method.

Results

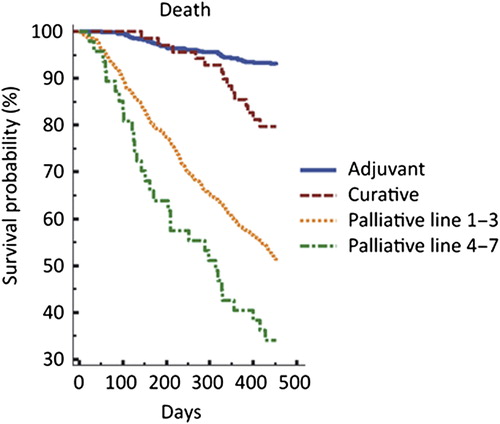

During the study period 2948 bookings, corresponding to 1460 patients, were recorded. Of the bookings, 383 (13%) were cancelled late. The majority of the patients, 95%, receiving palliative treatment, had only one or two previous of palliative treatment lines. Urological cancer was the tumor group with the highest percentage of late cancellations, 24% (n = 92). Followed by HNC-cancer 18% (n = 69), GI-cancer 14% (n = 54), gynecological cancer 11% (n = 42) and breast cancer and sarcoma 9% (n = 34), respectively. In bookings for palliative treatment, 16% (n = 286) was cancelled late, compared to 9% (n = 77) for the adjuvant and 8% (n = 20) for curative treatment bookings. Patient detoriation was the dominating cause for late cancellation, 51% (n = 196), followed by hematological toxicity 29% (n = 111), other toxicity 12% (n = 46), patient's choice 4% (n = 15) and administrative causes 4% (n = 15). The reason for late cancellation varied related to treatment indication. In patients with adjuvant treatment, 42% of the late cancellations were caused by hematological toxicity and 28% by patient detoriation, the corresponding figures for patients with palliative treatment were 25% and 59%, respectively (). Before the end of 2010, i.e. two months after their treatment was planned, 71 (4.9%) of the patients had died, 67 of them were booked for palliative treatment and four for adjuvant treatment. Early death was most common among patients with HNC-cancer (8%, n = 12), followed by GI-cancer (7%, n = 32), gynecological cancers (5%, n = 10), urological cancer (5%, n = 5) and breast cancer or sarcomas (2%, n = 12), respectively. Six months later, further 226 patients had died and at the end of 2011 another 168 patients had died. Survival according to treatment indication is shown in .

Table I. Late cancellations of bookings (number and %) in relation to treatment indication, total and according to reason of cancellation.

Women dominated with 70% of the patients compared to 30% for men. Patients in the age of 60–69 years were the largest group (36%), followed by 50–59 years (23%). Only 5% of the patients were under the age of 40 and 22% were over the age of 70 (). In percentage of the bookings, GI-cancer was the largest group (42%) followed by the breast cancer and sarcoma group (32%), HNC-cancer (11%), gynecological cancer (9%) and urological cancer (6%), respectively (). The treatment indication was palliative in 62%, adjuvant in 29% and curative in 9% of the bookings. The palliative bookings were distributed with 63% in first line, 22% in second line and 10% in third line. The distribution in treatment lines varied substantially between the diagnoses. Urological cancer (82.6%) followed by GI-cancer (73.6%) had the highest proportion treated in first line palliative treatment, while gynecological cancer (22.1%) followed by HNC-cancer (15.3%) registered the highest figures in third line (Supplementary Table I, to be found online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2014.990108). Only 5%(n = 48) were in later (4th–7th) lines of treatment. Of these, 24 had breast cancer, 18 gynecological cancers, four GI-cancer and two with HNC-cancer. To exemplify the diversity and how heterogeneous the group of oncological patients is, it was noticed that one patient with breast cancer was treated with pegylated doxorubin (6th line) and she was alive one year later. Another patient with gynecological cancer was treated with doxorubicin (7th line). That patient died less than two months after her last treatment. One patient, with adjuvant treatment, was over 90 years old in 2010. That patient suffered from an aggressive kind of parotid cancer and received adjuvant cetuximab in combination with radiotherapy after surgery. That patient was alive without relapse 28 months after completed adjuvant treatment. Of the 48 patients, treated in fourth to seventh line, 41 (85%) were alive after two months, 30 (63%) after eight months and 23 (48%) after 14 months respectively (). The majority of the bookings were to the four-day care units and only 2.5% (n = 71) were planned to be administered in one of the 24 h ward. From the bookings for single or combination treatments a total of 4538 individual drugs could be identified, fluorouracil was the most common drug (939 bookings), followed by cyclophosphamide (469 bookings), epirubicin (428 bookings) and paclitaxel (381 bookings). Trastuzumab (314 bookings), was the most used targeted drug (). The choice of treatment regimen varied between the three hospitals and in a sub-analysis of the two largest tumor groups, i.e. GI-cancer and breast cancer, the differences was analyzed. In GI-cancer the most common treatment at RH was gemcitabine single agent (15% of the bookings). In the two other hospitals fluorouracil in combination with irinotecan was the most common treatment regimen, either alone (SH, 18% of the bookings) or in combination with bevacizumab (DH, 18% of the bookings) (Supplementary Table II, to be found online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2014.990108). In patients with breast cancer, trastuzumab alone, given every third week, was by far the most common treatment in all hospitals, 25–27%. This reflects its large use in adjuvant therapy (67.5% of the trastuzumab- bookings). Paclitaxel weekly as a single agent was more commonly used at SH, (14% of the bookings), whereas the second most common therapy at DH was FEC-75 (12% of the bookings) Furthermore, there was a considerable difference between the hospitals in the use of vinorelbine as single-agent, at RH it was top two (12% of the bookings) while it was rarely used at SH (2% of the bookings) and not at all at DH (Supplementary Table III, to be found online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2014.990108).

Table II. Diagnoses, bookings and patients.

Table III. The most common drugs used in 2948 booked treatments.

Discussion

It is a challenge for the clinic that 13% of the treatments are cancelled within 48 h before the scheduled time. Patient detoriation is the dominating cause and explains 51% of the late cancellations. In bookings for palliative treatment this figure rises to 59%, compared to 35% for curative and 28% for adjuvant treatments. Could these numbers be reduced? A close monitoring to reveal if the patient develop unacceptable toxicity or signs of tumor progression, both indications for stopping the therapy, could be a possibility. One can hypothesize that an optimal and close monitoring would detect these symptoms earlier and the decision to cancel the treatment could thereby be made earlier than the last two days. Unfortunately PS is not routinely stated in the medical record, thus it was not possible to analyze. If the recording of PS significantly is improved it might serve as a tool to select patients in need of a closer monitoring during therapy. One of the great challenges in clinical oncology is to find the right balance between starting and continuing anti-tumor therapy and recommending best supportive care.

Late cancellation of treatment is not a topic frequently addressed in the literature. An Indian study showed that 16.2% of the elective operating bookings in a general surgical discipline were cancelled late due to the fact that the patient did not turn up on the scheduled day [Citation1]. A fully informed patient about practicalities before the treatment and the preparations is of course necessary. As could be expected, patients in the age of 50–79 dominated and constituted 77% of all patients. Younger patients (<50) represent 20% of the patients, which corresponds well to the relatively low cancer incidence in this age group, 6.9% of all male cancer and 13.2% of all female cancer in Sweden [Citation2]. Cancer incidence increases with age and patients 80 years or older represent 20.1% of all male cancer and 21.7% of all female cancer. However, in this survey they only represent 3% of the patients () which reflect the limited possibilities, due to higher risk of toxicity, for chemo- and targeted drugs in high age. It is also more likely that elderly patients do not come to an oncological clinic at the first place or that oncologists and the patient himself hesitate in starting anti- cancer treatment [Citation3,Citation4]. The reason for that is discussed previously [Citation3] and one reason for not treating elderly patients could be that chronological age instead of global health status is the argument for not treating a patient, although that is not clear. The three diagnoses with highest incidence in Sweden are prostate (15.7%), breast (14.9%) and colorectal (11.1%) cancer [Citation2]. The corresponding figures in this study are quite different, prostate (2.4%), breast (31.9%) and colorectal (29.9%). Breast cancer has a very long tradition of medical treatment and there are many possibilities in choosing different kinds of anti-tumor therapy [Citation5]. Medical treatment of colorectal cancer has undergone a fast development since the late 1980s when it was almost non-existent [Citation6]. Prostate cancer, however, was highly underrepresented in number of bookings indicating that few patients were offered intravenous treatment in 2010. Access to effective oral treatment is an important explanation, and that the possibilities for chemotherapy was not that common in 2010, something that has changed until present day [Citation3,Citation7]. Palliative treatment was the indication for 62% of the bookings. This reflects the increasing possibilities to improve quality of life and to prolong survival in patients even when cure is not possible. Where after, the medical improvements become available this figure can be expected to increase further. The variation between different diagnoses in treatment line distribution is substantial. This might be explained by varying tumor biology and availability of treatments. Hematological toxicity is one of the most common side effect from chemotherapy and caused nearly one third (29%) of all the late cancellations. In adjuvant (42%) and curative (35%) therapy these figures are and should be substantial, otherwise the treatment must be considered as under dosed. In our study 4% of the late cancellations were due to patient's choice and a similar figure due to administrative reasons. These figures are low but do still emphasize the importance of a close communication with the patient to reduce late changes.

The medical development is fast and encouraging with many new drugs being introduced and leading to improvements in clinical outcome. However, our oldest drugs, i.e. fluorouracil and cyclophosphamide are unchallenged as the most used ones, indicating that new drugs are used rather as a compliment than as a replacement (). Vinorelbine is recommended as a palliative treatment in breast cancer [Citation5]. A great variability in the use of vinorelbine between the three hospitals was seen. At RH 12% of the breast cancer bookings constituted vinorelbine compared to none at DH. However, vinorelbine is also available with an oral formulation which might have been used. Since oral treatment was not included in the survey the difference cannot fully be explained. The patient selection is crucial and criticism is often heard that oncologists tend to overuse medical treatment in a terminal phase of malignant disease. However, in this survey, 95% of the patients with palliative treatment were treated within the first three lines of therapy. Only 73 patients were given treatment in their fourth to seventh line of treatment. Furthermore, this group of patients did not have a survival very different from those treated in first to third line, indicating a reasonable patient selection (). It can be completely wrong to start first line treatment in a detoriated patient with a less chemo-sensitive disease and the right decision to start seventh line treatment in a fit patient who earlier demonstrated a highly chemo-sensitive disease. This illustrates the oncologists everyday struggle – how do I know that my patient benefit from the treatment? In our study, 71 patients died within two months after treatment was planned and that is also a challenge to reduce these numbers. Earlier studies have enlightened the problem in starting anti-tumor treatment too close to death, which might be in conflict with enrollment to a palliative care unit [Citation8,Citation9]. It was shown in another study that patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) were less likely to receive hospice care but gained nothing in survival when treated in a late phase (closer than 14 days to death) of the disease with chemotherapy [Citation10]. Recently, a study from Norway [Citation11] described the situation in their region where 10% of the patients received chemotherapy earlier than 30 days before end of life. PS and lab parameters, CRP and albumin, were included variables trying to identify parameters that could help the physician predicting prognosis, a difficult but necessary work [Citation12]. Frigeri et al. [Citation13] studied 231 patients with advanced pancreatic cancer receiving chemotherapy close to death to find clinical or laboratory factors that could predict shorter survival. None of the measured factors were significant in a multivariate analysis. Physicians in general are inaccurate in predicting prognosis for the patients [Citation14]. The Glascow Prognostic Score, based on those laboratory parameters mentioned before, CRP and albumin concentration, has been suggested as a helpful tool [Citation15]. A presentation, not published, at the Annual General Meeting of the Swedish Society of Medicine in 2006 oncologists presented a study consisting 100 patients when the physician was asked to predict probability of response of planned treatment, first line metastatic colorectal cancer. The result was that the physician actually was accurate in predicting which patient who was going to respond to the therapy initiated [Citation16]. Bigger and randomized studies are important to show what and when the physician can predict prognosis and what objective measurements that could be helpful in that process. In a Canadian register study it was shown that 22.4% of the patients had indication of aggressive cancer treatment during last 14 days of life. Furthermore, this figure increased during the study period 1993–2004 [Citation17]. In our survey, only 4.9% of the patients died within two months, indicating that the problem seems to be minor. Recently, another survey, also from Stockholm, showed that, in their population of 346 patients, 54% received oncological treatment and 32% were given treatment also during their last month of life [Citation18]. Oral treatment was more common for the patients treated close to death and since oral treatment was not included in this survey it might, at least partly, explain the difference. Best supportive care and/or hospice care should be introduced earlier for some patients. It is important to have that discussion with patients suffering from incurable cancer. This is also the recommendation from The Swedish National palliative Group in the national guidelines [Citation19]. A study from the US including 2155 patients describes that 73% of the patients with stadium IV lung cancer or colorectal cancer received an end-of-life discussion with a physician, but only 27% of them were performed by an oncologist. The most common place for that dialogue to take place was in the Emergency ward [Citation20]. The US Guidelines recommend that physicians bring up an end-of-life talk with all patients when life expectancy is less than one year [Citation21].

This work emphasizes the need of a regular monitoring of the therapy practice. Thereby can changes and differences be detected, analyzed and form a fundament for a constant treatment discussion and harmonization. This process is increasingly important in the light of the many new therapies emerging and increasing financial restrictions. The computerized system for prescription of chemotherapy, which has been introduced at the clinic during 2012 and 2013, will probably give this opportunity. The costs due to late cancellations were not analyzed in this survey. However, every treatment being cancelled late is a disappointment for that patient who was not prepared and furthermore there is a risk that resources are wasted instead of used for another patient, anxiously waiting to start treatment.

Supplementary material available online

Supplementary Tables I–III to be found online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2014.990108.

ionc_a_990108_sm6170.pdf

Download PDF (28.6 KB)Acknowledgments

Mats Hellström, Department of Oncology, Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, for creating a database and valuable technical support. Data previously reported as an abstract at the Annual General Meeting of the Swedish Society of Medicine in 2011.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Garg R, Bhalotra AR, Bhadoria P, Gupta N, Anand R. Reasons for cancellation of cases on the day of surgery – a prospective study. Indian J Anaesth 2009;53:35–9.

- Cancer Incidence in Sweden 2012. The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare: Stockholm; 2014.

- Lissbrant IF, Garmo H, Widmark A, Stattin P. Population-based study on use of chemotherapy in men with castration resistant prostate cancer. Acta Oncol 2013;52:1593–601.

- Garbay D, Maki RG, Blay JY, Isambert N, Piperno Neumann S, Blay C, et al. Advanced soft-tissue sarcoma in elderly patients: Patterns of care and survival. Ann Oncol 2013; 24:1924–30.

- >National Guidelines. Swedish Breast Cancer Group 2013.

- Goodwin RA, Asmis TR. Overview of systemic therapy for colorectal cancer. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2009;22: 251–6.

- Prezioso D, Galasso R, Di Martino M, Iapicca G, Annunziata E, Iacono F. Actual chemotherapeutical possibilities in hormone-refractory prostate cancer (HRPC) patients. Anticancer Res 2007;27:1095–104.

- Magarotto R, Lunardi G, Coati F, Cassandrini P, Picece V, Ferrighi S, et al. Reduced use of chemotherapy at the end of life in an integrated-care model of oncology and palliative care. Tumori 2011;97:573–7.

- Saito AM, Landrum MB, Neville BA, Ayanian JZ, Earle CC. The effect on survival of continuing chemotherapy to near death. BMC Palliat Care 2011;10:14.

- Nakano K, Yoshida T, Furutama J, Sunada S. Quality of end-of-life care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer in general wards and palliative care units in Japan. Support Care Cancer 2012;20:883–8.

- Anshushaug M, Gynnhild MA, Kaasa S, Kvikstad A, Grønberg BH. Characterization of patients receiving palliative chemo- and radiotherapy during end of life at a regional cancer center in Norway. Acta Oncol Epub 2014 Aug 27.

- Glare P, Sinclair C, Downing M, Stone P, Maltoni M, Vigano A. Predicting survival in patients with advanced disease. Eur J Cancer 2008;44:1146–56.

- Frigeri M, De Dosso S, Castillo-Fernandez O, Feuerlein K, Neuenschwander H, Saletti P. Chemotherapy in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: Too close to death? Support Care Cancer 2013;21:157–63.

- Christakis NA, Lamont EB. Extent and determinants of error in physicians’ prognoses in terminally ill patients: Prospective cohort study. West J Med 2000;172:310–13.

- Laird BJ, Kaasa S, McMillan DC, Fallon MT, Hjermstad MJ, Fayers P, et al. Prognostic factors in patients with advanced cancer: A comparison of clinicopathological factors and the development of an inflammation-based prognostic system. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19:5456–64.

- Berglund, Å, Byström P, Frödin J-E, Nygren P, Glimelius B. Prognostik, prediktion och behandlingsutvärdering vid cytostatikabehandling av metastatisk colorektal cancer. Annual General Meeting of the Swedish Society of Medicine, 2006.

- Ho TH, Barbera L, Saskin R, Lu H, Neville BA, Earle CC. Trends in the aggressiveness of end-of-life cancer in the universal health care system of Ontario, Canada. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:1587–91.

- Randén M, Helde-Frankling M, Runesdotter S, Strang P. Treatment decisions and discontinuation of palliative chemotherapy near the end-of-life, in relation to socioeconomic variables. Acta Oncol 2013;52:1062–6.

- National guidelines for palliative care. Sweden. 2012–2014. National Board of Health and Welfare: Stockholm; 2014.

- Mack JW, Cronin A, Taback N, Huskamp HA, Keating NL, Malin JL, et al. End-of-life care discussions among patients with advanced cancer: A cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2012;156:204–10.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Palliative care. Available from: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physicians_gls/PDP/palliative.pdf [Cited 13th June 2014].