Abstract

Background. Evidence for the safety and benefits of exercise training as a therapeutic and rehabilitative intervention for cancer survivors is accumulating. However, whereas the evidence for the efficacy of exercise training has been established in several meta-analyses, synthesis of qualitative research is lacking. In order to extend healthcare professionals’ understanding of the meaningfulness of exercise in cancer survivorship care, this paper aims to identify, appraise and synthesize qualitative studies on cancer survivors’ experience of participation in exercise-based rehabilitation.

Material and methods. Five electronic databases (PubMed, PsychINFO, EMBASE, Cinahl and Scopus) were searched systematically for articles published up to May 2014 using keywords and MeSH terms. To be included, studies had to contain primary data pertaining to patient experiences from participation in supervised, structured moderate to vigorous-intensity exercise.

Results. In total 2447 abstracts were screened and 37 papers were read in full. Of these, 19 studies (n = 390) were selected for inclusion and critically appraised. Synthesis of data extracted from eight studies including in total 174 patients (77% women, age 28–76 years) exclusively reporting experiences of participation in structured, supervised exercise training resulted in nine themes condensed into three categories: 1) emergence of continuity; 2) preservation of health; and 3) reclaiming the body reflecting the benefits of exercise-based rehabilitation according to cancer survivors. Accordingly, the potential of rebuilding structure in everyday life, creating a normal context and enabling the individual to re-establish confidentiality and trust in their own body and physical potential constitute substantial qualities fundamental to the understanding of the meaningfulness of exercise-based rehabilitation from the perspective of patients.

Conclusions. In addition to the accumulating evidence for the efficacy of exercise training in cancer rehabilitation, it is incumbent upon clinicians and policy-makers to acknowledge and promote the meaningfulness of exercise for the individual, and to use this knowledge to provide new solutions to current problems related to recruitment of underserved populations, long-term adherence and implementation.

Exercise therapy following a cancer diagnosis is one area of cancer rehabilitation with solid evidence for efficacy [Citation1]. Specifically, previous research indicates that structured exercise training is safe for cancer survivors and produce improvements in fitness, strength, physical function, and cancer-related psychosocial variables [Citation2]. Moreover, a growing number of epidemiological studies suggest a significant inverse relationship between self-reported exercise behavior and cancer-specific mortality or progression in survivors of breast cancer [Citation3], colon cancer [Citation4] and prostate cancer [Citation5], respectively. Meanwhile, recent studies [Citation6,Citation7] show that cancer survivors continue to report more sedentary behavior than non-cancer individuals, and although structured exercise training has emerged as an important factor to enhance cancer survivorship outcomes [Citation8], exercise training recommendations and/or exercise-based rehabilitation programs are not part of standard clinical management following a cancer diagnosis [Citation9]. Incorporating exercise into clinical practice, including reaching individuals not already motivated to join an exercise program, demands clinical knowledge consisting of interpretive action and interaction involving questions and phenomena that cannot all be controlled, measured, and counted by means of quantitative methods [Citation10]. Thus, the impact of the contextual dimensions [Citation11] of exercise-based rehabilitation, e.g. human interactions, the organization of the intervention, the staff, the timing, the physical surroundings or the general atmosphere, remains relatively unknown. By allowing for the exploration of social events as experienced by individuals in their natural context [Citation10], qualitative research methods may contribute to a broader understanding of the contextual dimensions of exercise-based cancer rehabilitation, which may be of importance in the application, implementation and dissemination of structured exercise training programs in clinical practice. Consequently, qualitative research within the field of exercise-oncology has delivered important knowledge on cancer survivors’ exercise preferences, and motivation and barriers for exercise in diverse cancer populations. However, despite the value of this knowledge, the generalizability of isolated qualitative studies is low and has not yet to be analyzed in systematic ways to expedite the transfer of disparate qualitative findings into clinical practice and policymaking [Citation12]. Thus, whereas the evidence for the efficacy of exercise training has been established in several meta-analyses [Citation13–18], synthesis of the findings from qualitative research providing an understanding of the meaningfulness of exercise-based rehabilitation from the perspective of the individual cancer survivor is lacking.

Meta-synthesis has evolved as a rigorous method for integrating findings from multiple qualitative studies to produce a new interpretation of findings that is more substantive than those resulting from individual investigations [Citation19]. Consequently, meta-syntheses give clinicians greater access to qualitative findings as they are integrated into a single paper [Citation19].

This paper aims to identify, appraise and synthesize qualitative studies on cancer survivors’ experience of participation in exercise-based rehabilitation. This knowledge may enable healthcare professionals to extend their understanding of the meaningfulness of exercise, which may serve to support the promotion and implementation of exercise in cancer survivorship care.

Method

Inclusion criteria

To be included, studies had to contain primary data pertaining to experience from and/or social interaction during structured, supervised moderate to vigorous-intensity exercise-based cancer rehabilitation. A range of methods (e.g. interviews, participant observation) and approaches (e.g. phenomenology, grounded theory, or etnography) were eligible for inclusion. Papers written in English and published up to May 2014 were considered. Studies using mixed methods were included only if qualitative findings were presented separately from the quantitative results. Only papers involving adults were considered.

Exclusion criteria

Papers that focused on home-based, unsupervised or self-initiated exercise training or physical activity were excluded, as were those that centered on mind-body interventions (e.g. mindfulness, imagery, relation therapy, breathing exercise, yoga) and other types of non-vigorous exercise (e.g. tai-chi, stretching, qui-gong).

Search strategy and selection of included studies

Identification of qualitative research papers for this meta-synthesis was conducted through a systematic search of five electronic databases (PubMed, PsychINFO, EMBASE, Cinahl and Scopus) using keywords and MeSH terms. The literature search was carried out by a librarian subject specialist (AL) in close collaboration with the first author (JM) and DMB. Initially, titles were screened for their potential relevance by the first author (JM). Following this initial stage, two reviewers (JM and NMH) examined the abstracts of references that appeared relevant to the review or lacked adequate information from the title to make a decision. Subsequently, we performed a full-text examination to check that identified papers met the inclusion criteria. Two others reviewers (CA and MJ) considered papers on which there was a lack of agreement, and a final decision about their inclusion was resolved through discussion. Finally, reference lists of included papers were hand searched for potential additional studies.

Assessment of quality

In order to ensure that research included in this meta-synthesis was adequately robust, we employed the CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Program) qualitative research checklist (score range from 0 to 9). The first author and at least one other reviewer (NMH, CA or MJ) independently assessed the methodological quality of the papers meeting the inclusion criteria (n=19). Any disagreement on assessment was resolved through discussion with a third reviewer.

Data extraction and synthesis

In the analysis process we extracted, aggregated, interpreted and synthesized findings from papers illuminating patient perspectives on participation in exercise-based rehabilitation exclusively. As such, findings from studies on related topics (e.g. pain, fatigue, return to work, program feasibility) were excluded from the meta-synthesis. The meta- synthesis approach was inspired by the guidelines for synthesizing qualitative research developed by Sandelowski and Barroso [Citation20] including six steps: 1) reading of each paper several times; 2) extraction of findings relating to experiences of exercise-based rehabilitation across the papers, i.e. the extracted data consisted of findings reported by authors in the Results sections of the included studies; 3) visual mapping of selected key findings; 4) clustering and translating the findings into themes; 5) re-reading of each individual paper; and 6) final description of themes and assigning of the theme titles (categories). At this final stage, the primary reviewer (JM) offered an interpretation of the relationships between the themes including key characteristics. The new interpretation was critically considered by all reviewers and validated by the first authors of the included papers not already involved in the study group.

Results

Characteristics of the included studies (n = 19)

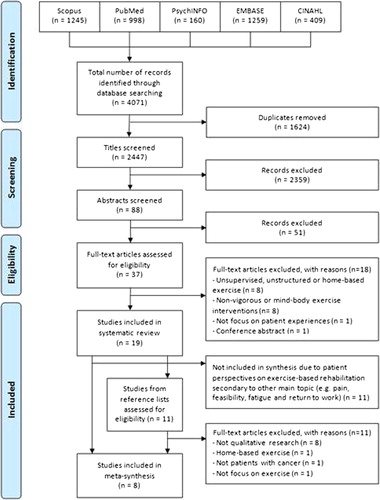

The search yielded a final total of 2447 papers after removing duplicates. Of these, 37 were read in full, and 19 studies [Citation21–39] were selected for inclusion and critically appraised. The hand search of the reference lists of the 19 studies resulted in 11 studies not included in the electronic search. These were retrieved in full text but were all subsequently excluded. Details of the search and its results are shown in .

Figure 1. Flow diagram of studies identified, appraised and included in the meta-synthesis, with reasons for exclusion at each stage.

The majority of participants (n = 390) in the studies included in the systematic review were women (68.7%). Interventions were predominantly group-based (16/19) and lasted from 6 weeks and up to 12 weeks. In 11 of 19 studies the population was comprised of mixed diagnoses. Ten studies included patients undergoing treatment [Citation21,Citation26,Citation27,Citation30–34,Citation37,Citation38], five studies included patients post-treatment [Citation24,Citation28,Citation35,Citation36,Citation39], while two studies [Citation22,Citation23] included both. One study [Citation24] included palliative patients and in one case [Citation29] treatment status was not informed. The most frequent data collection method applied was in-depth, semi-structured individual interviews (9/19) and focus group interviews (5/19); however, one study used patient diaries [Citation27] and two studies used participant observation [Citation26,Citation29]. Supplemenary Table I, to be found online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2014.995777 presents key features and quality scores of the 19 papers [Citation21–39] included in the systematic review.

Quality appraisal

Quality scores (of 9) ranged from 6 to 9 with a mean score of 7.7 indicating a generally good quality of research across all papers. However in 12 of the 19 papers a third reviewer was involved to reach consensus between researchers. Typical methodological flaws included suboptimal explanation of recruitment strategy and discussion of saturation of data. Moreover, the papers typically failed to provide sufficient critical examination of the researchers’ role.

Synthesis (n=8)

Three main themes were identified across the eight studies [Citation21–28] included in the meta-synthesis: Emergence of continuity including the subthemes new purpose, goal-setting and positive distraction, Preservation of normality including the subthemes social support, autonomy and affirmation of own health, and Reclaiming the body including the subthemes enhanced performance, safety trough professional supervision and overcoming barriers. presents a summary of the themes, sub-themes and sample quotations identified in the studies included in the meta-synthesis.

Table I. Summary of the categories, themes and sample quotations identified in the studies included in the meta-synthesis (n = 8).

Emergence of continuity

This theme includes the subthemes new purpose, goal-setting and positive distraction, and reflects the psychological benefits of exercise-based rehabilitation including the potential of exercise to recapture the loss of continuity and consistency provoked by the disease and treatment.

New purpose

A prevalent and substantial quality of exercise-based rehabilitation is the potential of exercise to re-install structure in everyday life. The fact that exercise may be planned ahead, give the participants something to look forward and a feeling of purposefulness, influence and self-worth, including getting out of the house [Citation21,Citation23]. Specifically, female survivors in Emslie et al. [Citation21] explained how attending exercise classes resembled going to work, which provided a feeling of control. Moreover, gaining a positive attitude to dealing with their cancer including a new purpose was reported by McGrath et al. [Citation22]. Also, the structure imposed by exercise on everyday life was seen by survivors both as a prerequisite and welcomed consequence of building an exercise routine long-term [Citation28].

Goal-setting

A quality of exercise is that it may be closely monitored, measured, and recorded, which makes it possible to document positive progression and personal achievements [Citation23,Citation26,Citation27], which for some is the reason for enrollment in exercise [Citation21,Citation26] or synonymous with the very purpose of exercise maintenance [Citation28]. Paltiel et al. [Citation25] emphasized how exercise helped patients in palliative care to establish a goal of physical gain, while Midtgaard et al. [Citation27] pointed out how goal attainment may support the individual's belief in new opportunities including a feeling of being able to carry out desired actions.

Positive distraction

Participants undergoing treatment in the study by Bulmer et al. [Citation23] described how exercise provided a structured retreat from the day-to-day focus on their disease including a respite from anxiety and fear of dying, whereas post-treatment survivors emphasized participation in exercise as a moderator of unexpected emotions and fear of recurrence [Citation23,Citation28]. However, it should be noted also, that participation in structured exercise training may have the opposite effect in individuals experiencing pain and poor performance as described by Midtgaard et al. [Citation27] including patients with advanced disease. As such, rather than a permanent removal or alleviation of uncertainty, exercise may be said to provide a welcomed distraction defined as ‘the nice part of not being well’ [Citation21] or a ‘lifeline’ [Citation23].

Preservation of normality

This theme includes the subthemes social support, autonomy, and affirmation of own health and reflects the social benefits of exercise-based rehabilitation including the potential of group-based exercise to create a social context characterized by reciprocal approval/recognition and mutual encouragement. This allows the individual to preserve a normal identity and escape the otherwise dominant patient role.

Social support

Even though the experience of participation in exercise is subjective, it appears inseparable from the social involvement including giving and receiving social support from peers. Luoma et al. [Citation24] emphasized how peer support was important for relieving stigma as the social interaction resembled normal life, e.g. at their workplace, while McGrath et al. [Citation22] described the social component as ‘an enormous boost’ to the participants’ morale. Another important benefit of the group involvement, is the effect of the group on the individual's motivation (commitment) and performance during sessions/classes [Citation21,Citation25], including empathy and solidarity, described by Paltiel et al. [Citation25] as being associated with a possibility to verbally interact but with non-committal relationships and by Emslie et al. [Citation21] as ‘a kind of informal counseling and support’.

Autonomy

Participation in exercise may facilitate the discovery of physical capabilities and help survivors redefine themselves as potentially ‘fit and athletic’ [Citation23,Citation27]. Bruun et al. [Citation26] described how the participants through exercise felt able to fulfill their desire to take action and assume responsibility in promoting their own health [Citation26], while participants in [Citation21,Citation24,Citation27] described feeling a sense of mastery over their disease, and promoting and enabling a switch/transition in identity from being a cancer patient to being a healthy individual again. Similarly, women in Bulmer et al.'s study [Citation23] described their exercise sessions as ‘empowering’ and how they felt proud of having done something positive and proactive for their health. Participants indicated that the focus on doing something constructive about their physical condition through exercise gives a sense of competence and increased confidence at a time when life seems out of control [Citation22].

Affirmation of own health

Participation in exercise-based rehabilitation was described by participants as an affirmation of their healthy status. In Bulmer et al.'s study [Citation23], the exercise sessions were viewed by participants undergoing active treatment as positive, proactive steps to improve health. Similarly, McGrath et al. [Citation22] described how exercise may provide survivors with a positive and well supported perspective on their condition. In comparison, post-treatment survivors experienced exercise as a means to create distance from their previous status as a cancer patient [Citation23] and an investment in healthy living potentially protecting them from disease recurrence [Citation28].

Reclaiming the body

This theme includes the subthemes enhanced performance, safety through professional supervision and overcoming barriers and reflects the physical benefits of exercise-based rehabilitation related to physical challenges enabling the individual to re-establish confidentiality and trust in their own body and physical potential.

Enhanced performance

Because participants feel that their physical fitness is impaired due to cancer treatments, physical recovery and the experience of enhanced performance is experienced as especially rewarding and motivating [Citation24,Citation26]. The survivors in Midtgaard et al.'s study [Citation28] explained how participation in exercise had offered them sufficient personal experience to feel certain that regular exercise is preferable to sedentary behavior in that it is rewarding especially in terms of reduced fatigue. Similarly Bulmer et al. [Citation23] emphasized how improvements in strength and aerobic conditioning from exercise enhanced women's confidence about re-engaging in pre-cancer activities and taking on new physical challenges.

Safety through professional supervision

It is crucial for the participants, that the professionals in charge of the intervention have knowledge of cancer and its consequences including knowledge of basic physiotherapy skills [Citation25]. When exercising under the supervision of health professionals, participants feel that they do not need to explain why their physical performance may be poor, nor why their movements may be restricted [Citation22,Citation24]. Luoma et al. [Citation24] described the importance of the instructor tailoring the classes so that the activity was manageable, though also challenging the participants to exercise intensely, like healthy persons [Citation24]. Accordingly, female survivors in Bulmer et al.'s study [Citation23] described their relationships with their trainers as ‘nurturing’, ‘encouraging’, and ‘comforting’. Also, access to professional expertise and/or extensive medical examinations is imperative to alleviate concerns about sore muscles and painful joints and to clarify the difference between feeling frail and being in poor physical shape [Citation24,Citation26].

Overcoming barriers

Changes in appearance is perceived by many survivors as a barrier to joining an ordinary exercise class [Citation21], whereas changed appearance is a common issue in exercise-based rehabilitation. During exercise-based rehabilitation, participants feel relieved that nobody stared or felt sorry for them because of their illness [Citation24]. Participants in Luoma et al.'s [Citation24] and Emslie et al.'s [Citation21] studies stressed the importance of exercising with women with similar experiences, since they felt that they did not need to take into account other people when they were undressing or taking a shower after the exercise. For some survivors, participation in exercise-based rehabilitation was also a way to overcome the barrier of feeling too frail to attend regular exercise groups [Citation24] or feeling self-conscious in front of others [Citation22].

Discussion

This review is the first to draw together qualitative research on the experiences of cancer survivors participating in exercise-based rehabilitation. The findings suggest that the potential of rebuilding structure in everyday life, creating a normal context and enabling the individual to re-establish confidentiality and trust in their own body and physical potential constitute substantial qualities. These qualities are fundamental to the understanding of the meaningfulness of exercise-based rehabilitation from the perspective of patients, and add to the current clinical evidence on physical activity by providing a substantive understanding of the patient perspective that cannot solely be measured and counted by means of standardized methods [Citation10]. Specifically, this meta-synthesis illustrates that cancer survivors prioritize and benefit from exercise because of a wish to maintain or rebuild a normal daily life, preserve or rebuild their personal identity and feel in control of or (re)united with their body/physical self.

Although not motivated by the being together with other cancer survivors per se, the findings in this review indicate that cancer survivors appreciate the opportunity to exercise at a place where the physical limits of the body or altered appearance caused by the disease and the treatments are non-judgmentally accepted and sympathetically understood. Being in a context where everyone is familiar with the diagnosis of cancer, and the ways in which it may affect the body, participating in activities that are synonymous with health and self-determination, exempts the individual from the role as patient and may reduce the risk of perceived stigma, which may in itself be associated with an elevated risk of depression in cancer [Citation40]. As such, the findings provide an understanding and explanation of the evidence of the effect of exercise on quality of life and depression/emotional wellbeing. Especially the opportunity to set goals implying a positive outlook and sense of directedness is a quality and an ability that is in direct contrast to the symptomatology of depression including lack of initiative and pleasure [Citation41,Citation42]. It appears from the findings in this review, that exercise may be a way for the individual cancer survivor to reinstall predictability and comprehensibility in their life known to be fundamental to a positive self-rated health despite illness [Citation43]. Also, exercise appears to serve as a means to achieve a sense of continuity whereby the individual may feel less alienated from themselves, their friends and family described by Little et al. [Citation44] as a major task for survivors with reference to the experience of discontinuity caused by the cancer illness. As such, by participating in structured exercise the individual is offered a positive and potent narrative synonymous with new possibilities and hope including negotiation of positive outcomes [Citation45]. However, regarding preservation of normality, including affirmation of own health, it should be noted also, that some cancer survivors appear to be motivated to exercise because of a (religious) wish to protect themselves from disease recurrence as described both in the study by Midtgaard et al. [Citation28] and in the study by McGrath et al. [Citation22]. As such, when promoting the meaningfulness of exercise to cancer survivors, health professionals need to be aware of the risk of self-blame in patients who experience disease recurrence and the risk of provoking or enhancing fear of recurrence in disease-free survivors. Evidence-based practical guidelines for exercise coaching of cancer survivors, taking into account the potential of exercise to create new meaning in the life of the individual, have been published previously by Midtgaard [Citation45].

Although exercise has proven in some qualitative studies (e.g. [Citation26,Citation29]) to be especially appealing to male survivors otherwise reluctant to participate in rehabilitation, this review indicates that female survivors profit from exercise to the same extent as their male counterparts with regard to the experience of control and self-reliance. Thus, while some of the important qualities of exercise lie in its potential to facilitate a male-sensitive context based on active, rational, and action-oriented activities rather than verbalized emotional support, these exact qualities should be recognized also as equally beneficial and attractive for female survivors. More studies are warranted to conclude whether the meaningfulness of exercise-based rehabilitation is transferable to children and/or adolescents with cancer, as the context of interventions including these populations is likely to be different from the contexts examined in the studies included in this synthesis.

The motivational aspect of the group setting was emphasized in most studies (e.g. [Citation21,Citation37]), and supports the implementation of group-based exercise. However, given the time-limitedness of most structured and often center-based programs, the importance of the group could equally offer a potential explanation of the often modest/suboptimal levels of long-term (post-intervention) adherence. More studies critically examining the risk of participants in structured, group-based programs becoming too dependent on the support from health professionals and peers to transfer their experience to ‘real life’ settings outside the intervention are warranted. In this regard, community-based, time-unlimited exercise opportunities, such as dragon boat racing [Citation46–48], may be superior to center-based, structured interventions in terms of improved/better long-term adherence. However, more research is needed to demonstrate whether programs that are unsupervised by health professionals and less structured possess the same psychological qualities as the interventions examined for the purpose of this review.

Methodological considerations

This meta-synthesis is dependent on the studies included, and it is possible that important publications might have been missed as we only included English language studies. Also, we did not conduct ‘berry-picking’ [Citation20], i.e. performed footnote chasing, grey literature searches, author searching and hand searching selected journals, and may have retrieved just a sample of all relevant studies in the field. Nine of 19 papers included in the systematic review, and three of the papers included in the meta-synthesis were authored by one or two of the reviewers involved in this study, however the decision to include them was reached in consensus. Moreover, the synthesis as presented in the Results section of this study has been approved by 7/8 of the first authors of the included papers. Specifically, we emailed all authors asking them if the integrity of their original research was intact following our meta-synthesis, including whether they felt that their work had been misinterpreted or extrapolated beyond the limits of the data. Only minor changes were made on this basis, supporting the trustworthiness of the novel interpretation presented in this study. However, the synthesis of the qualitative framework is a dynamic process, and it is possible that other researchers would have arrived at a different interpretation.

Conclusion

The findings in this meta-synthesis suggest that cancer survivors experience participation in exercise-based rehabilitation as a means to fulfill their mental, social and physical wellbeing independent of disease status. In addition to the accumulating evidence for the efficacy of exercise training in cancer survivorship, it is incumbent upon clinicians and policy-makers to acknowledge that exercise-based rehabilitation involves human behavior and interaction, which is both informed and mediated by context [Citation11]. Accordingly, the effect of structured exercise cannot be properly interpreted and promoted without taking into account the meaningfulness of exercise, and the use of this knowledge may provide new solutions to current problems related to recruitment, adherence and implementation.

Supplementary material available online

ionc_a_995777_sm6543.pdf

Download PDF (44.4 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the study participants of the included papers who generously shared their experiences. Moreover we wish to acknowledge the commitment of Dr. Hanne Paltiel, Dr. Pam McGrath, Dr. Sandra M Bulmer and Dr. Carol Emslie, who kindly responded to our invitation to review the results of the meta-synthesis.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Stubblefield MD, Hubbard G, Cheville A, Koch U, Schmitz KH, Dalton SO. Current perspectives and emerging issues on cancer rehabilitation. Cancer 2013;119(Suppl 11):2170–8.

- Pekmezi DW, Demark-Wahnefried W. Updated evidence in support of diet and exercise interventions in cancer survivors. Acta Oncol 2011;50:167–78.

- Holmes MD, Chen WY, Feskanich D, Kroenke CH, Colditz GA. Physical activity and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. JAMA 2005;293:2479–86.

- Meyerhardt JA, Heseltine D, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, Saltz LB, Mayer RJ, et al. Impact of physical activity on cancer recurrence and survival in patients with stage III colon cancer: Findings from CALGB 89803. J Clin Oncol 2006;24: 3535–41.

- Kenfield SA, Stampfer MJ, Giovannucci E, Chan JM. Physical activity and survival after prostate cancer diagnosis in the health professionals follow-up study. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:726–32.

- Williams K, Steptoe A, Wardle J. Is a cancer diagnosis a trigger for health behaviour change? Findings from a prospective, population-based study. Br J Cancer 2013;108:2407–12.

- Kim RB, Phillips A, Herrick K, Helou M, Rafie C, Anscher MS, et al. Physical activity and sedentary behavior of cancer survivors and non-cancer individuals: Results from a national survey. PLoS One 2013;8:e57598.

- Jones LW, Alfano CM. Exercise-oncology research: Past, present, and future. Acta Oncol 2013;52:195–215.

- Lakoski SG, Eves ND, Douglas PS, Jones LW. Exercise rehabilitation in patients with cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2012;9:288–96.

- Malterud K. The art and science of clinical knowledge: Evidence beyond measures and numbers. Lancet 2001;358: 397–400.

- Hansen HP, Tjornhoj-Thomsen T, Johansen C. Rehabilitation interventions for cancer survivors: The influence of context. Acta Oncol 2011;50:259–64.

- Finfgeld-Connett D. Generalizability and transferability of meta-synthesis research findings. J Adv Nurs 2010;66:246–54.

- Fong DY, Ho JW, Hui BP, Lee AM, Macfarlane DJ, Leung SS, et al. Physical activity for cancer survivors: Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br Med J 2012;344:e70.

- Brown JC, Huedo-Medina TB, Pescatello LS, Ryan SM, Pescatello SM, Moker E, et al. The efficacy of exercise in reducing depressive symptoms among cancer survivors: A meta-analysis. PLoS One 2012;7:e30955.

- Jones LW, Liang Y, Pituskin EN, Battaglini CL, Scott JM, Hornsby WE, et al. Effect of exercise training on peak oxygen consumption in patients with cancer: A meta-analysis. Oncologist 2011;16:112–20.

- Cramp F, James A, Lambert J. The effects of resistance training on quality of life in cancer: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer 2010;18:1367–76.

- Speck RM, Courneya KS, Masse LC, Duval S, Schmitz KH. An update of controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv 2010;4:87–100.

- Schmitz KH, Holtzman J, Courneya KS, Masse LC, Duval S, Kane R. Controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2005;14:1588–95.

- Finfgeld DL. Metasynthesis: The state of the art – so far. Qual Health Res 2003;13:893–904.

- Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. New York: Springer; 2007.

- Emslie C, Whyte F, Campbell A, Mutrie N, Lee L, Ritchie D, et al. ‘I wouldn't have been interested in just sitting round a table talking about cancer’; exploring the experiences of women with breast cancer in a group exercise trial. Health Educ Res 2007;22:827–38.

- McGrath P, Joske D, Bouwman M. Benefits from participation in the chemo club: Psychosocial insights on an exercise program for cancer patients. J Psychosoc Oncol 2011;29:103–19.

- Bulmer SM, Howell J, Ackerman L, Fedric R. Women's perceived benefits of exercise during and after breast cancer treatment. Women Health 2012;52:771–87.

- Luoma ML, Hakamies-Blomqvist L, Blomqvist C, Nikander R, Gustavsson-Lilius M, Saarto T. Experiences of breast cancer survivors participating in a tailored exercise intervention – a qualitative study. Anticancer Res 2014;34:1193–9.

- Paltiel H, Solvoll E, Loge JH, Kaasa S, Oldervoll L. “The healthy me appears”: Palliative cancer patients’ experiences of participation in a physical group exercise program. Palliat Support Care 2009;7:459–67.

- Bruun DM, Krustrup P, Hornstrup T, Uth J, Brasso K, Rorth M, et al. “All boys and men can play football”: A qualitative investigation of recreational football in prostate cancer patients. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2014;24(Suppl 1):113–21.

- Midtgaard J, Stelter R, Rorth M, Adamsen L. Regaining a sense of agency and shared self-reliance: The experience of advanced disease cancer patients participating in a multidimensional exercise intervention while undergoing chemotherapy – analysis of patient diaries. Scand J Psychol 2007;48:181–90.

- Midtgaard J, Rossell K, Christensen JF, Uth J, Adamsen L, Rorth M. Demonstration and manifestation of self-determination and illness resistance – A qualitative study of long-term maintenance of physical activity in posttreatment cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 2012;20:1999–2008.

- Adamsen L, Rasmussen JM, Pedersen LS. ‘Brothers in arms’: How men with cancer experience a sense of comradeship through group intervention which combines physical activity with information relay. J Clin Nurs 2001;10:528–37.

- Adamsen L, Midtgaard J, Andersen C, Quist M, Moeller T, Roerth M. Transforming the nature of fatigue through exercise: Qualitative findings from a multidimensional exercise programme in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2004;13:362–70.

- Adamsen L, Andersen C, Midtgaard J, Moller T, Quist M, Rorth M. Struggling with cancer and treatment: Young athletes recapture body control and identity through exercise: Qualitative findings from a supervised group exercise program in cancer patients of mixed gender undergoing chemotherapy. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2009;19:55–66.

- Adamsen L, Stage M, Laursen J, Rorth M, Quist M. Exercise and relaxation intervention for patients with advanced lung cancer: A qualitative feasibility study. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2012;22:804–15.

- Andersen C, Rorth M, Ejlertsen B, Adamsen L. Exercise despite pain – breast cancer patient experiences of muscle and joint pain during adjuvant chemotherapy and concurrent participation in an exercise intervention. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2014;23:653–67.

- Burke SM, Brunet J, Sabiston CM, Jack S, Grocott MP, West MA. Patients’ perceptions of quality of life during active treatment for locally advanced rectal cancer: The importance of preoperative exercise. Support Care Cancer 2013;21:3345–53.

- Groeneveld IF, de Boer AG, Frings-Dresen MH. Physical exercise and return to work: Cancer survivors’ experiences. J Cancer Surviv 2013;7:237–46.

- Korstjens I, Mesters I, Gijsen B, van den Borne B. Cancer patients’ view on rehabilitation and quality of life: A programme audit. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2008;17:290–7.

- Midtgaard J, Rorth M, Stelter R, Adamsen L. The group matters: An explorative study of group cohesion and quality of life in cancer patients participating in physical exercise intervention during treatment. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2006;15:25–33.

- Rorth M, Madsen KR, Burmolle SH, Midtgaard J, Andersen C, Nielsen B, et al. Effects of Darbepoetin Alfa with exercise in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy: An explorative study. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2011;21:369–77.

- Spence RR, Heesch KC, Brown WJ. Colorectal cancer survivors’ exercise experiences and preferences: Qualitative findings from an exercise rehabilitation programme immediately after chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2011;20:257–66.

- Gonzalez BD, Jacobsen PB. Depression in lung cancer patients: The role of perceived stigma. Psychooncology 2012;21:239–46.

- Bultz BD, Carlson LE. Emotional distress: The sixth vital sign – future directions in cancer care. Psychooncology 2006;15:93–5.

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–70.

- Antonovsky A. Unraveling the mystery of health: How people manage stress and stay well, 1st ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1987.

- Little M, Paul K, Jordens CF, Sayers EJ. Survivorship and discourses of identity. Psychooncology 2002;11: 170–8.

- Midtgaard J. Theoretical and practical outline of the Copenhagen PACT narrative-based exercise counselling manual to promote physical activity in post therapy cancer survivors. Acta Oncol 2013;52:303–9.

- Courneya KS, Blanchard CM, Laing DM. Exercise adherence in breast cancer survivors training for a dragon boat race competition: A preliminary investigation. Psychooncology 2001;10:444–52.

- Mitchell TL, Yakiwchuk CV, Griffin KL, Gray RE, Fitch MI. Survivor dragon boating: A vehicle to reclaim and enhance life after treatment for breast cancer. Health Care Women Int 2007;28:122–40.

- Parry DC. The contribution of dragon boat racing to women's health and breast cancer survivorship. Qual Health Res 2008;18:222–33.