Abstract

Background. In parallel with the rising incidence of cancer and improved treatment, there is a continuous increase in the number of patients living with cancer as a chronic condition. Many cancer patients experience long-term disability and require continuous oncological treatment, care and support. The aim of this review is to evaluate the most recent data on the effects of rehabilitation among patients with advanced cancer.

Material and methods. A systematic review was conducted according to Fink's model. Only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published in 2009–2014 were included. Medline/PubMed and Cochrane databases were searched; five groups of keywords were used. The articles were evaluated for outcome and methodological quality.

Results. Thirteen RCTs (1169 participants) were evaluated. Most studies were on the effects of physical exercise in patients with advanced cancer (N = 7). Physical exercise was associated with a significant improvement in general wellbeing and quality of life. Rehabilitation had positive effects on fatigue, general condition, mood, and coping with cancer.

Conclusions. Rehabilitation is needed also among patients with advanced disease and in palliative care. Exercise improves physical performance and has positive effects on several other quality of life domains. More data and RCTs are needed, but current evidence gives an indication that rehabilitation is suitable and can be recommended for patients living with advanced cancer.

As the incidence and prevalence of cancer increases, so does the number of patients living with cancer as a chronic condition. Patients also live longer with advanced cancer (i.e. locally advanced or metastatic incurable cancer) than in previous decades [Citation1]. Thus, the need for rehabilitation among patients with advanced cancer will increase. Since advanced cancer is rarely compatible with employment and since the condition may consume considerable healthcare resources, a major public health concern arises. Timely rehabilitation at appropriate volumes could save healthcare costs [Citation2], ensure better functional capacity, maintain the quality of life (QoL), and provide an opportunity for independent life for the patient [Citation3].

The number of elderly cancer survivors will increase as the population ages. Elderly patients with cancer usually have more severe impairments and comorbidities than younger patients [Citation4] and thus the rehabilitation needs of the elderly are different from those of younger patients [Citation5]. Prevention and management of pain, fatigue, deconditioning, functional impairment, cognitive decline, and peripheral neuropathy appear to be the most effective measures to prolong the active life expectancy of elderly patients with advanced cancer [Citation6].

Comorbidities in patients with advanced cancer are associated with a need for physical rehabilitation, for emotional, family-oriented rehabilitation, and for participation in physical-related rehabilitation activities [Citation7]. Rehabilitation of cancer patients aims at reducing the impact of disabling and limiting conditions resulting from cancer and its treatment. It aims at enabling patients to regain their social integration and participation in societal life [Citation8].

For many people with advanced cancer, survival means living with a chronic and complex condition. Many patients end up with long-term disabilities requiring ongoing care and support. Since these impairments are often undetected or untreated, disability may ensue [Citation3]. The symptoms and impairments may be related to the cancer itself but also to the treatments, as well, and the occurrence of treatment-related impairment among cancer survivors may increase in parallel with the number of treatments [Citation9,Citation10].

Functional impairment is often accompanied with significant psychosocial morbidity [Citation1]. Up to 15–25% of people with advanced cancer experience depression, and many experience anxiety, pain, and fears triggered by the uncertainties of a diagnosis of advanced cancer [Citation11,Citation12]. Patients with progressive disease experience also muscle weakness, which impacts adversely on their autonomy and QoL [Citation13].

Improved oncological treatment adds years to the life of patients with advanced cancer. It has also been shown that rehabilitation can add life to those years [Citation6]. Research stresses the need for rehabilitation also among patients with advanced disease, but at the same time rehabilitation is not used sufficiently [Citation3]. The reasons for its suboptimal use are a lack of information about the benefits of rehabilitation, a lack of referrals by oncologists, and a lack of resources [Citation1].

The aim of this review is to systematically evaluate what is known about rehabilitation of patients with advanced or chronic cancer, what kind of rehabilitation is currently available for this patient group, what are the needs for rehabilitation among these patients, and to identify where more research is needed in the future.

Material and methods

Databases

This report is based on a systematic data review. The data were collected from the Medline/PubMed and Cochrane databases, and the review of the literature was carried as described by Fink [Citation14]. The main focus was on the most recent literature and on studies published in 2009–2014 (until September 22, 2014).

Search terms and inclusion criteria

The following search terms were used: “advanced” AND “cancer” AND “rehabilitation”; “chronic” AND “cancer” AND “rehabilitation”; “palliative” AND “cancer” AND “rehabilitation”; “supportive care” AND “advanced cancer”; “advanced” AND “breast cancer” AND “rehabilitation”.

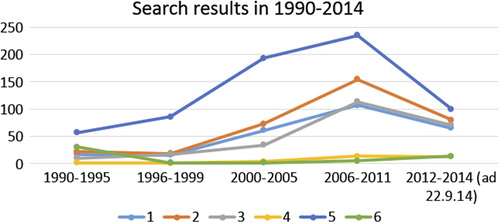

The terms “advanced AND cancer AND rehabilitation” and “chronic AND cancer AND rehabilitation” gave most of the hits. We also examined the evolution of the number of studies published from 1990 to 2014. There were very few previous research reports before the year 2000 ().

Figure 1. Number of published articles by search terms in 1990–2014. 1 = Advanced AND cancer AND rehabilitation, 2 = Chronic AND cancer AND rehabilitation, 3 = Palliative AND cancer AND rehabilitation, 4 = Advanced AND breast cancer AND rehabilitation, 5 = Supportive care AND advanced AND cancer, 6 = All Cochrane search hits.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for selection of the articles are presented in .

Table I. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for selection of articled included in the review.

Data extraction

The search results yielded titles of articles. Articles whose titles did not fit the research topic or did not respond to the study questions were excluded. Articles on pharmacological or radiation treatment of cancer and articles on treatment models were also excluded. Thereafter, only articles which referred to advanced/chronic/palliative cancer and rehabilitation were included.

The titles and abstracts of all included studies were checked for relevance concerning the research topic. Randomized controlled trials, controlled clinical trials, and systematic reviews were included at first. Two authors (M.S. and R.N.) assessed independently the identified titles and abstracts and made proposals to include or exclude these articles. A third author (T.S. for palliative articles, and L.P. for all other articles) evaluated these two independent proposals and made the final decision of inclusion or exclusion of the articles based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria (). Each reviewer assessed the studies for relevance and methodological quality.

Thereafter key data from each study were extracted and transferred to a table with predesigned headings. All authors read the selected articles and came to consensus on the final selection of pertinent articles.

Description of data and databases

A total of 4863 studies were originally identified by search terms in the Medline/Pubmed and Cochrane databases.

Medline/Pubmed

In total 4796 articles were found. Of these, 597 were included based on the first inclusion criteria, after reading of the titles there were 147 potentially suitable articles left, and after removal of duplicates, 75 articles remained for abstract review. Finally, 34 articles were left for full text reading.

Cochrane

Thirty-nine articles were found. Of these, 19 were approved after review of the inclusion criteria. Of these, four were duplicates. After abstract review, 14 articles were left for full test reading.

In total, 48 studies were selected for full text reading, and finally, 13 RCT studies (1169 participants) were selected for this review (). In addition, 17 suitable good quality reviews were identified, and all of them are included in this article.

Table II. The summary table for content and quality assessment of randomized controlled studies included in the review.

Assessment of methodological quality

The methodological quality of the articles was assessed independently by R.N. and M.S., who used the AMSTAR method (A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews). This method has originally been developed to evaluate the methodological quality of systematic reviews [Citation15], but it is also used to evaluate the quality of individual clinical studies. It comprises 11 concise criteria; each criterion is given a score of 1 if it is met or a score of 0 if it is not met, or if it is unclear or not applicable. The individual scores are then added to give a final score. An AMSTAR score of 8–11 implies high quality, 4–7 medium quality, and 0–3 poor quality.

Results

Characteristics of studies

The 13 included studies are summarized in . Seven of the included RCTs were based on physical exercise intervention [Citation16–19,Citation21–23] alone or as a part of the rehabilitation. Most studies included mixed diagnostic groups of patients with advanced cancer.

Two studies [Citation24,Citation25] were based on self- management rehabilitation of patients with advanced breast cancer. One study [Citation2] focused on the cost-effectiveness of rehabilitation and one on swallowing rehabilitation [Citation26] of patients with head and neck cancer, one on cognitive-behavioral intervention [Citation27], and one on psycho-education [Citation28]. There were five studies from USA and Canada, six from Europe (two from the Nordic countries), and two from Asia. The mean sample size of the intervention and control groups was 90 (range 24–231) patients. All patients were adults (> 18 years).

The studies were rated according to AMSTAR from 7 to 10 and had high (N = 10) or medium (N = 3) methodological quality. None of the systematic reviews reported conflicts of interest as currently required. AMSTAR was highly feasible and applicable to systematic reviews of RCTs.

Physical exercise interventions

The physical exercise studies originated from 2010 to 2014 (N = 7 studies and n = 596 patients).The studies included patients with mixed diagnostic groups of advanced cancer, e.g. breast, prostate and hematological cancer.

Physical exercise had a beneficial impact on the physical wellbeing, fatigue, depression, and overall QoL [Citation16,Citation17]. Patients with advanced cancer experienced improved functional mobility following exercise rehabilitation [Citation17] and reduced anxiety, stress, and depression. Fatigue, shortness of breath, constipation, and insomnia were alleviated [Citation18].

A combination of physical exercise and massage reduced pain and improved mood in patients with terminal cancer [Citation19]. It increased muscle mass and muscle strength, and improved physical function [Citation20]. Routine exercise reduced some of the complications associated with immobility (e.g. weakness, poor cardiopulmonary function) [Citation17]. In addition, standardized resistive physiotherapy was feasible during radiation therapy. It was associated with preserved physical wellbeing in patients with advanced cancer [Citation21].

Football training has been studied in men with advanced prostate cancer undergoing androgen deprivation therapy. Football training for 12 weeks improved lean body mass and muscle strength compared with usual care [Citation22].

Both resistance training and aerobic exercise training were feasible for patients with advanced gastrointestinal cancer undergoing chemotherapy, and training seemed to improve cancer-related symptoms as well as the patients’ physical activities of daily living [Citation23].

Overall, physical activity was effective in maintaining the QoL of patients with advanced cancer [Citation16], and maintained the independent function for as long as possible. Home-based exercise improved mobility, reduced fatigue, and improved the sleep quality of patients with advanced cancer [Citation18]. Rehabilitation reduced the unmet needs of cancer survivors and was also cost-effective [Citation2].

Self-management of breast cancer patients

The self-management programs of breast cancer survivors improved the QoL of patients compared with usual care. These programs helped patients to manage the numerous medical, emotional, and role tasks on their own better than patients not attending these programs. Self-management enabled people with chronic cancer to live their lives effectively [Citation24].

Educational information, cognitive restructuring, coping skills enhancement, and relaxation resulted in significant improvement of overall QoL, health and functioning. The socioeconomic, psychological, and spiritual wellbeing of self-managing patients with advanced breast cancer was better than of controls [Citation25].

Other aspects of rehabilitation

A study involving patients with advanced head and neck cancer examined the impact of two different interventions for swallowing rehabilitation [Citation26]. Pretreatment rehabilitation was feasible and could improve the functional outcomes of patients. Further, a form of cognitive-behavioral intervention reduced the pain, fatigue, and sleep disturbances experienced by patients with different types of advanced cancers [Citation27].

Rehabilitation in palliative care

A form of psycho-educational intervention reduced the breathlessness, fatigue, and anxiety experienced by patients with lung cancer [Citation28]. The input of a multidisciplinary team was beneficial with regard to the psychological wellbeing and QoL of hospice patients and reduced significantly the unmet need for supportive care of cancer patients [Citation2].

Most of the rehabilitation studies in palliative and hospice care are based on physical therapy (typically, massage and exercise training). Exercise programs improved cancer-related symptoms and the patients’ physical activities of daily living. These programs enabled patients to cope better with their everyday life [Citation19,Citation23]. Also home-based exercise programs appeared to improve the mobility, reduce the fatigue, and improve the sleep quality of patients with advanced cancer [Citation18].

Discussion

This systematic review shows that there are few studies on the impact of rehabilitation on patients with advanced cancer. The available results suggest that physical and psychosocial rehabilitation can improve symptom control, physical function, psychological wellbeing, and the QoL of this patient group. Physical rehabilitation is beneficial even in the palliative stage of cancer.

The current evidence on the effects of rehabilitation is, however, based on small studies, usually with only a limited number of patients. The results of these small studies are probably suggestive at best, and no definitive conclusions can be drawn. More data are needed.

From the quality point of view of the studies, the numbers of included studies and participants were small and the attrition rates in many studies were high. In some studies the results were not reported according to intention-to-treat principle and there was some variation of the methodological quality across the studies.

The quality of the studies was evaluated according to AMSTAR summary score. AMSTAR proved easy to apply to systematic reviews of randomized studies. The fact that it has been validated, gives credibility to its use as a quality assessment tool. Although summary scores may mask inherent strengths and weaknesses of systematic reviews, these scores can also prove to be helpful in informing decision making.

Goals of rehabilitation of patients with advanced cancer

Since patients with advanced cancer experience significant physical and psychological morbidity, minimizing disability and distress is very important [Citation11]. Patients also require ongoing care and support, which need to be well-coordinated, prevention-focused, and involve ongoing surveillance while minimizing and managing co-morbidities and any long-term adverse effects of treatment [Citation29]. Pain, fatigue, dyspnea, and anxiety are common symptoms among patients with advanced cancer. Healthcare providers need to be aware of these problems and be sensitive to assessing, preventing, and treating these symptoms which have a profound negative impact of the QoL of these patients [Citation24].

For patients living with advanced cancer, the rehabilitation goals are usually different from those of cured survivors. The main aim is often to help the patient to live a good life irrespective of disabilities. The goal of rehabilitation may help a person to regain control over many aspects of his life and to remain as independent and productive as possible [Citation3,Citation30].

The goal of rehabilitation is to minimize the adverse consequences of treatment and to support the psychosocial adaptation of the patient. Most interventions are intended for patients after their initial diagnosis and treatment. However, when long-term survival is uncertain or impossible, the right concept would be to focus on good living short-term. The role of relatives, friends, and caregivers is crucial [Citation11,Citation31].

Different cancers and associated conditions require different means and approaches of rehabilitation. Rehabilitation must thus be individualized and flexible. It is also important to evaluate the goals of rehabilitation frequently and to reset the rehabilitation targets accordingly.

Benefits of rehabilitation of patients with advanced cancer

Rehabilitation of cancer patients is intended to support the hopes of patients and their families and to maintain and improve the patients’ QoL [Citation32]. Rehabilitation improves the physical, social, and psychological endurance of patients. This will help patients to cope with the limitations caused by the cancer and its treatment. Rehabilitation helps patients to become more independent and less reliant on caregivers and to adjust to actual, perceived, and potential losses caused by advanced cancer. Rehabilitation can also reduce the number of hospitalizations [Citation3].

Psychosocial rehabilitation can also improve the patients’ physical condition. Patients with untreated depression or anxiety may be less likely to continue health promoting habits and take their cancer medication e.g. because of fatigue or a lack of motivation. They may also withdraw from family and other social support systems, which means that they will not ask for the emotional and financial support they need to be able to cope with their cancer. This may, in turn, increase stress and feelings of despair [Citation33].

Physical exercise rehabilitation may provide substantial physiological and psychological benefits for cancer patients [Citation34]. Exercise reduces anxiety, stress, and depression [Citation35]. Lung cancer patients who exercise experience positive changes in exercise capacity, symptoms, and some domains of health-related QoL [Citation8,Citation36]. Versatile and multi-disciplinary physical rehabilitation clearly supports independent living, physical fitness, and overall wellbeing also among patients with advanced cancer [Citation16,Citation17,Citation20], and it reduces some of the complications associated with immobility [Citation17]. Based on these results we feel confident in stating that exercise complemented with psychological support supports the survival of cancer patients.

It is important to realize that rehabilitation activities are not linked to any specific facility or hospital. Home-based exercise programs appear to improve mobility, reduce fatigue, and improve sleep quality of patients with advanced cancer [Citation18]. Rehabilitation could thus have an instrumental role in the management of patients with progressive, advanced cancer. This raises the question of whether rehabilitation activities should be instituted early in the course of the disease and be continued throughout the whole cancer continuum. For patients with advanced disease, it might be possible and feasible to implement a rehabilitation program where rehabilitation is initiated systematically while the patient is hospitalized. Hospital-based rehabilitation would benefit patients with obvious physical disadvantages and side effects of cancer or its treatment (e.g. [Citation26]). Hospital-based rehabilitation would also support the principle of continuity of the care. As the importance of rehabilitation is emphasized, the patient will be more eager to continue different forms of rehabilitation throughout the duration of the disease.

There is also undisputable evidence that psycho-educational rehabilitation boosts physical and mental wellbeing, and reduces fatigue and anxiety among lung cancer patients [Citation29]. Self-management programs improve the QoL of patients with advanced breast cancer. Self-management empowers patients with chronic cancer to live their lives effectively [Citation24]. More research is, nevertheless, needed on how different rehabilitation models affect the over-all wellbeing of patients with different types of cancer.

The most useful components of rehabilitation of patients with advanced cancer are not known. The ultimate goal, nevertheless, is to provide comprehensive and effective multi-professional rehabilitation also for this patient group. In addition to support provided by medical and nursing staff, effective and appropriate rehabilitation might include psychological and physical support and support by peers. Provision of detailed information tailored to the needs and receptive capacity of the patient is a natural part of rehabilitation, as well.

We found no adverse effects related to or caused by rehabilitation. All studies reported positive findings. There may, however, be reporting bias, i.e. only positive studies may have been published. On this basis, we can safely talk only about the benefits of rehabilitation – rather than the effects. The physical and psycho-educational rehabilitation and self- management programs do not have apparent adverse effects. Physical rehabilitation, in particular, produces a number of benefits for the patients.

Rehabilitation in palliative care

A large multicenter study including 461 advanced cancer patients showed that although the difference in the QoL (the primary endpoint of the study) was non-significant between groups receiving early palliative intervention versus standard cancer care, early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer was associated with benefit to some patients [Citation37]. These interventions also include a rehabilitative attitude and maintenance of physical and psychosocial performance.

In palliative care, exercise programs have beneficial effects on fatigue and QoL [Citation38]. Palliative care rehabilitation programs affect positively the symptoms, physical functioning, functional capacities, muscle strength, emotional wellbeing, QoL, and even mortality and morbidity of cancer patients [Citation39]. For patients who are unable to undertake traditional forms of exercise, neuromuscular electrical stimulation may provide an alternative method of enhancing leg muscle strength [Citation13]. Exercise and rehabilitation are indeed very important approaches in hospice care and for palliation, but more controlled studies are needed to better assess the role of rehabilitation in palliative patient care [Citation39,Citation40].

Patients in palliative care benefit from physiotherapy and different types of art therapy, including music therapy. Music and voice therapy may be used as a form of rehabilitation in all stages of palliative care, because these forms of therapy may alleviate physical and psychological anxiety and pain [Citation41,Citation42]. The importance of early palliative care and rehabilitation for patients with advanced cancer has been recently emphasized [Citation28,Citation37].

Spiritual and social needs can be met with focus group meetings. These meetings may be attended not only by patients and nursing staff but also, and importantly, by family members, spouses, and volunteer workers. At these meetings the persons convene for sharing thoughts of hope: hope for good care, hope for life continuing despite the cancer disease, hope for good hospice care [Citation43].

Rehabilitation in palliative care units demonstrate that effective nurturing the idea of living instead of waiting for deterioration and death carries a strong rehabilitative effect. It is important to empower patients, and the role of healthcare professionals is to support patients’ self-care. The basic idea of rehabilitation is not to work for but to work with the patient [Citation44].

Rehabilitation of patients with advanced cancer: Considerations for the future

It is obvious that more high-quality studies with large sample sizes are needed, although current evidence clearly indicates that same forms of rehabilitation (physical, psychological, and social support) used after primary treatment are effective for patients with advanced disease.

The Cancer Society of Southwest Finland has long-term experience of rehabilitation of patients with advanced cancer. It has become evident that the key forms of intervention for optimal patient rehabilitation and adaptation are cognitive, psychosocial, and peer support. Rehabilitation may take the form of functional activities and different elements of art (e.g. painting, literature, music, and voice control). Information and peer support help the rehabilitee to accept cancer as a part of life, to improve coping skills, and to enhance a sense of coherence and empowerment [Citation38,Citation39].

In Finland, the concept of rehabilitation has also been introduced in palliative care units and hospices, since patients in palliative care have several rehabilitation needs related to their activities of daily living, disruption of usual routines and roles, and anxieties about being a burden to others. Important targets for rehabilitation in this patient group are alleviation of pain and easing of the burden of caregivers [Citation3]. If these rehabilitation needs are not adequately identified, patients will receive only suboptimal help in living and coping with their disabilities.

The future of cancer rehabilitation should rest on a multi-professional and multi-faceted approach with focus on the support of the patient's physical, psychological, and social wellbeing, i.e. the patient's condition and needs. This does not belittle the importance of physical rehabilitation emphasized [Citation40].

Implications for future research

This review has its strengths and limitations. The systematic literature review used precise inclusion and exclusion criteria, the AMSTAR measurement tool was used to verify the quality of the review, and several keywords were used.

However, the data on advanced cancer rehabilitation are limited, studies are heterogeneous, and the results are by necessity summarized only briefly. The number of studies on rehabilitation in advanced cancer is limited and most studies are relatively small. More studies are needed to determine which subpopulations of patients with advanced cancer benefit from specific forms of rehabilitation, which interventions are the most effective, how individual rehabilitation needs are met, and how the effectiveness of rehabilitation should be measured.

Most of the evidence on the effects of rehabilitation is based on different forms of physical activity. Still, more research is needed to establish the optimal type of exercise training, the optimal setting for delivery, and the safety of different interventions for different cancer patient populations.

Further studies are also needed to establish which kind of rehabilitation best alleviates pain and fatigue and supports the independence and QoL of patients. More data are needed to assess the cost-effectiveness of rehabilitation among patients with advanced cancer.

The challenge for the future is to design rehabilitation based on the individual cancer patient's needs. Assessment of the needs and appropriate tools to perform these assessments are needed.

Conclusions

Rehabilitation is needed for patients with advanced disease and in palliative care. Exercise improves physical performance and has positive effects on several other domains of QoL. Effective rehabilitation also improves the overall QoL.

More data and RCTs are needed on the efficacy and the safety of rehabilitation of patients with advanced cancer. The current evidence, albeit limited, gives an indication that rehabilitation can be recommended for patients with cancer as a chronic condition and for cancer patients in palliative care.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Cheville A. Rehabilitation of patients with advanced cancer. Cancer 2001;92(4 Suppl):1039–48.

- Jones L, Fitzgerald G, Leurent B, Round J, Eades J, Davis S, et al. Rehabilitation in advanced, progressive, recurrent cancer: A randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013;46:315–25.

- Silver JK, Baima J, Mayer RS. Impairment-driven cancer rehabilitation: An essential component of quality care and survivorship. CA Cancer J Clin 2013;63:295–317.

- Gardner JR, Livingston PM, Fraser SF. Effects of exercise on treatment-related adverse effects for patients with prostate cancer receiving androgen-deprivation therapy: A systematic review. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:335–46.

- Balducci L, Fossa SD. Rehabilitation of older cancer patients. Acta Oncol 2013;52:233–8.

- Gupta AD, Lewis S, Shute R. Patients living with cancer – the role of rehabilitation. Aust Fam Physician 2010;39:844–6.

- Holm LV, Hansen DG, Kragstrup J, Johansen C, Christensen Rd, Vedsted P, et al. Influence of comorbidity on cancer patients’ rehabilitation needs, participation in rehabilitation activities and unmet needs: A population-based cohort study. Support Care Cancer 2014;22:2095–105.

- Weis J, Giesler JM. Rehabilitation for cancer patients. Recent Results Cancer Res 2014;197:87–101.

- Payne C, Wiffen PJ, Martin S. Interventions for fatigue and weight loss in adults with advanced progressive illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;1:CD008427.

- Cavalheri V, Tahirah F, Nonoyama M, Jenkins S, Hill K. Exercise training undertaken by people within 12 months of lung resection for non-small cell lung cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;7:CD009955.

- Chochinov H. Depression in cancer patients. Lancet Oncol 2001;2:499–505.

- Kandasamy A, Chaturvedi SK, Desai G. Spirituality, distress, depression, anxiety and quality of life in patients with advanced cancer. Indian J Cancer 2011;48:55–9.

- Maddocks M, Gao W, Higginson IJ, Wilcock A. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation for muscle weakness in adults with advanced disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 1:CD009419.

- Fink A. Conducting research literature reviews: From the internet to the paper. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc.; 2005.

- Shea J, Grimshaw M, Wells A, Boers M, Andersson N, Hamel C, et al. Development of AMSTAR: A measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2007;7:10.

- Oldervoll LM, Loge JH, Lydersen S, Paltiel H, Asp MB, Nygaard UV, et al. Physical exercise for cancer patients with advanced disease: A randomized controlled trial. Oncologist 2011;16:1649–57.

- Litterini AJ, Fieler VK, Cavanaugh JT, Lee JQ. Differential effects of cardiovascular and resistance exercise on functional mobility in individuals with advanced cancer: A randomized trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2013;94:2329–35.

- Cheville AL, Kollasch J, Vandenberg J, Shen T, Grothey A, Gamble G. et al. A home-based exercise program to improve function, fatigue, and sleep quality in patients with Stage IV lung and colorectal cancer: A randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013;45:811–21.

- López-Sendín N, Alburquerque-Sendín F, Cleland JA, Fernández-de-las-Peñas C. Effects of physical therapy on pain and mood in patients with terminal cancer: A pilot randomized clinical trial. J Altern Complement Med 2012; 18:480–6.

- Stene GB, Helbostad JL, Balstad TR, Riphagen II, Kaasa S, Oldervoll LM. Effect of physical exercise on muscle mass and strength in cancer patients during treatment – a systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2013;88;573–93.

- Cheville AL, Girardi J, Clark MM, Rummans TA, Pittelkow T, Brown P, et al. Therapeutic exercise during outpatient radiation therapy for advanced cancer: Feasibility and impact on physical well-being. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2010;89:611–9.

- Uth J, Hornstrup T, Schmidt JF, Christensen JF, Frandsen C, Christensen KB, et al. Football training improves lean body mass in men with prostate cancer undergoing androgen deprivation therapy. Scan J Med Sci Sports 2014;24(Suppl 1): 105–12.

- Jensen W, Baumann FT, Stein A, Bloch W, Bokemeyer C, de Wit M, et al. Exercise training in patients with advanced gastrointestinal cancer undergoing palliative chemotherapy: A pilot study. Support Care Cancer 2014;22:1797–806.

- Loh SY, Packer T, Chinna K, Quek KF. Effectiveness of a patient self-management programme for breast cancer as a chronic illness: A non-randomised controlled clinical trial. Cancer Surviv 2013;7:331–42.

- Gaston-Johansson F, Fall-Dickson JM, Nanda JP, Sarenmalm EK, Browall M, Goldstein N. Long-term effect of the self-management comprehensive coping strategy program on quality of life in patients with breast cancer treated with high-dose chemotherapy. Psychooncology 2013;22:530–9.

- Van Der Molen L, Van Rossum MA, Rasch CR, Smeel LE, Hilgers FJ. Two year results of a prospective swallowing rehabilitation trial in patients treated with chemoradiation for advanced head and neck cancer. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2014;271:1257–70.

- Kwekkeboom KL1, Abbott-Anderson K, Cherwin C, Roiland R, Serlin RC, Ward SE. Pilot randomized controlled trial of a patient-controlled cognitive-behavioral intervention for the pain, fatigue, and sleep disturbance symptom cluster in cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 2012;44:810–22.

- Chan CW, Richardson A, Richardson J. Managing symptoms in patients with advanced lung cancer during radiotherapy: Results of a psycho educational randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage 2011;41:347–57.

- Phillips J, Currow D. Cancer as a chronic disease. Collegian 2010;17:47–50.

- Cheville AL, Kornblith AB, Basford JR. An examination of the causes for the underutilization of rehabilitation services among people with advanced cancer. Rehabil 2011;90: 27–37.

- Tamagawa R, Garland S, Vaska M, Carlson LE. Who benefits from psychosocial interventions in oncology? A systematic review of psychological moderators of treatment outcome. J Behav Med 2012;35:658–73.

- Okamura H. Importance of rehabilitation in cancer treatment and palliative medicine. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2011;41:733–8.

- Massie MJ. Prevalence of depression in patients with cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2004;(32):57–71.

- Spence RR, Heesch KC, Brown WJ. Exercise and cancer rehabilitation: A systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev 2010;36:185–94.

- Albrecht TA, Taylor AG. Physical activity in patients with advanced-stage cancer: A systematic review of the literature. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2012;16:293–300.

- Granger CL, McDonald CF, Berney S, Chao C, Denehy L. Exercise intervention to improve exercise capacity and health related quality of life for patients with non-small cell lung cancer: A systematic review. Lung Cancer 2011;72:139–53.

- Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, Hannon B, Leighl N, Oza A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014;383:1721–30.

- Development of cancer prevention, early detection, and rehabilitative support 2014–2025. National Cancer Plan, Part II. Directions 6/2014. 115 pages. Helsinki, Finland: National Institute for Health and Welfare; 2013.

- Eva G, Wee B. Rehabilitation in end-of-life management. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2010;4:158–62.

- Nurminen R, Salakari M, Lämsä P, Kemppainen T. Syöpäsairaiden ja heidän läheistensä kuntoutuksen tuloksellisuus. Teoksessa Nurminen R, Ojala K. Tuloksellisuus syöpäsairaiden kuntoutuksessa. Turku: Turun ammattikorkeakoulun raportteja 118; 2011. p. 82–101 (in Finnish).

- Archie P, Bruera E, Cohen L. Music-based interventions in palliative cancer care: A review of quantitative studies and neurobiological literature. Support Care Cancer 2013;21: 2609–24.

- Dileo C. Therapeutic use of voice with imminently dying patient. In: Baker F, Uhling S, editors. Voicework in music therapy. Research and practice. London/Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2011. p. 3213–30.

- Kylmä J, Duggleby W, Cooper D, Molander G. Hope in palliative care: An integrative review. Palliat Support Care 2009;7:365–77.

- Johnston B, McGill M, Milligan S, McElroy D, Foster C, Kearney N. Self-care and end of life care in advanced cancer: Literature review. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2009;13:386–98.